Around 610 CE, a merchant meditating in a cave outside Mecca began to receive a series of revelations. From that vision grew Islam, one of the world’s great religions. What Islam’s prophet, Muhammad, began gave rise to a number of mighty empires. Islam proved to be such a powerful force that today, 1,400 years after a vision appeared to the Prophet, it is the world’s second largest religion. With more than one billion adherents, Islam has deep roots in the Asia, Africa, and Europe. More than half of today’s Muslims live in Asia alone, from Turkey to Indonesia. Worldwide, a tremendous variety of people follow Islam—from blue-eyed Bosnians to African Americans to the Uighurs of western China. After fourteen centuries, Islam remains one of the world’s fastest-growing faiths.

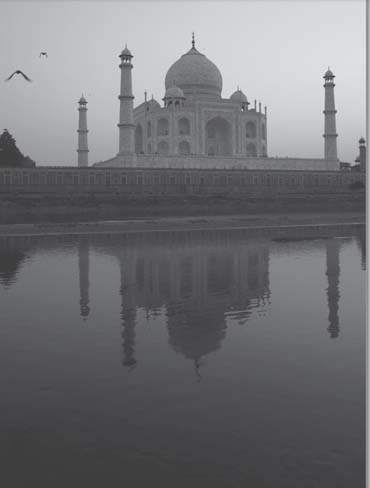

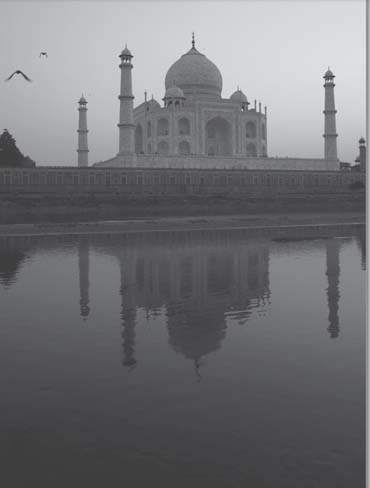

But Islam, by virtue of extremist acts that pressed its name into the consciousness of many as the 21st century was just beginning, faces a new hurdle. With the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001 in the United States—and subsequent attacks in Bali, London, Madrid, and elsewhere—radical Islam seized global attention. The images, headlines, and aftermath of each attack indelibly linked those events with the name of Islam. In spite of the attention seized by Muslim extremists in recent history, however, the broader history of Islam is one of astonishing growth and great achievement. Islam itself is complex and multifaceted, and its faithful have, over centuries, been massively prolific in works of science, philosophy, theology, and the arts. From the luminous symmetry of the Taj Mahal to algebraic equations, from the tales of The Thousand and One Nights to the collected works of poets such as Rumi or Hafiz, Islam has provided a rich tapestry of contributions to world culture.

What binds Muslims? Muslims believe in one God and affirm Muhammad as His prophet. They hold Islam to be the third revelation of monotheism—after Judaism and Christianity—and as such revere many of the prophets honoured in Jewish and Christian tradition, including Abraham, Noah, Moses, and Jesus. Muslims also share several spiritual guides. One is the Qur’an, the sacred scripture of Islam revealed by God to Muhammad and, for all Muslims, the very word of God. Another is the Hadith, the record of the traditions or sayings of the Prophet, revered by Muslims as a major source of religious law and moral guidance and second only to the authority of the Qur’an.

Incumbent upon every Muslim are five duties known collectively as the Five Pillars of Islam. First among these is the recitation of a profession of faith called the shahadah (“There is no god but God and Muhammad is His prophet”), which must be recited by a Muslim at least once in his or her lifetime. In addition, observant Muslims say prayers five times a day, give to charity, fast during the holy month of Ramadan, and, if they are able, make a pilgrimage to Mecca, Muhammad’s birthplace. In addition to the Five Pillars, many Muslims around the world also study the Qur’an.

In this book, you will learn why Arabia was such fertile ground for the emergence of a new faith. In its prehistorical period (3000 BCE–500 CE), the dry Arabian Peninsula, most of which was unfavourable for settled agriculture, derived great wealth from its prime location at an important trade crossroads: caravans crisscrossed the desert bringing goods from China, India, and Africa in the East to trade as far as Spain in the West. For hundreds of years, Arabia’s residents served as middlemen in this trade; thus, although agricultural opportunity may have been limited, commercial opportunity was almost limitless.

In 570, Muhammad was born in Mecca, already an important Arabian trading and religious centre, in what is known as Islam’s formation and orientation period (500-634 CE). Muhammad was a serious young man whose parents had died when he was young; he was raised for a short time by his grandfather, and then by his uncle, Abu Talib. He later worked for a wealthy businesswoman named Khadijah, whom he married at age 25. Full of spiritual questions, Muhammad often sought the solitude of the desert to think and pray. It was on one such trip that the 40-year-old Muhammad had a revelation. The angel Gabriel came to him, saying three times “Recite!” and told Muhammad that he was the messenger of God. Muhammad went home, relating to Khadijah what had happened. Soon she became Islam’s first convert.

The revelations persisted, and after several years of preaching to his family and friends, Muhammad started delivering his revelations to others in the form of public recitations. Although a number of prominent Meccans became believers, many others harassed his supporters, forcing some of them into a period of exile. During this difficult time, Muhammad faced the deaths of two of his dearest companions: Khadijah, his wife and confidant, as well as his beloved uncle and protector, Abu Talib. And yet, in spite of the challenges, Muhammad’s flock continued to grow. In 622 he moved his followers in small, inconspicuous groups to the city of Yathrib (Medina) in an emigration known as the Hijrah. In Medina Muhammad established Islam as a religious and social order. From there, Muhammad later led campaigns against his opponents, including Mecca; by 629 he was able to lead his followers on the first peaceful pilgrimage to that city. He continued to receive revelations until his death in 632.

After the Prophet Muhammad’s passing, the Muslim faithful learned to survive as a community in the period of conversion and crystallization (634–870 CE). First, four “rightly guided” caliphs, all friends or relatives of Muhammad, ruled from 632 to 661. These leaders stretched Islam’s borders by taking over Palestine, Egypt, Syria, and parts of Iraq. They also organized the government.

One important event was a controversy over ‘Ali, the pious cousin and son-in-law of Muhammad, who was the last of these caliphs. ‘Ali faced many difficulties, including the opposition of Mu‘awiyah, the governor of Syria. But ‘Ali had supporters, too, called the Shi‘at ‘Ali, or Partisans of ‘Ali. In 661, ‘Ali was murdered. After ‘Ali’s assassination, Mu‘awiyah assumed the caliphate, founding the Umayyad dynasty. That injustice—and later the murder of ‘Ali’s son al-Husayn by Umayyad troops—angered the Shi‘ites. They opposed the Umayyads’ more secular rule and decided to follow spiritual leaders called imams. Thus began a separation between two branches of Islam: the Sunni, who make up 85 percent of Muslims today, and the Shi‘ah, who constitute the remainder.

Meanwhile, the Umayyad empire flourished. The Umayyads, who ruled from Damascus, Syria, expanded their empire all the way from the western Mediterranean into Central Asia. They also made use of the dhimmi system in managing their heterogenous empire. Under this arrangement, Jews and Christians were not forced to convert to Islam, but they did have to pay a special tax for living in the empire. This way, the empire encouraged but did not force religious conversion. In fact, most of the future Islamic empires had systems in place that made room for religious minorities in their midst. In many of these empires, Christians and Jews would even have privileged places in the government and the military. In 750 a new dynasty, the ‘Abbasids, overthrew the Umayyads and began to rule from a new capital city, Baghdad.

During the period of fragmentation and florescence (flowering) that took place between 870 and 1041, the ‘Abbasid empire became a centre for art and science. After Chinese papermakers were captured in battle in 751, Muslim artisans learned how to make paper for books. Literature spread quickly. Great works were translated from ancient Greek, Sanskrit, Syriac, and other languages into Arabic. These new ideas encouraged the development of schools of philosophy (falsafah, adapting the word from Greek). Muslim scholars made contributions to the sciences in fields such as algebra, astronomy, botany, chemistry, and medicine. They became experts at map-making and navigation. Over time, regional dynasties began to develop, too, such as the Fatimids, who captured Egypt and created a new capital, Cairo.

Although Islam was blooming, it faced obstacles and hostilities that ultimately caused it to redirect and thrive in new ways. During the period of migration and renewal, from 1041 to 1405, broad in-migration and assimilation played an especially crucial role. As part of this trend, a number of Muslim cities were attacked by outsiders. Christian Crusaders captured Jerusalem, a city holy to Christians, Muslims, and Jews, in 1099. The Crusaders were finally forced from Jerusalem by Saladin, a powerful Muslim leader, in 1187. In 1258, the Mongols—pagan, horse-riding tribes of the Central Asian steppe—invaded Baghdad, where they slaughtered hundreds of thousands of residents and terminated the caliphate. Ironically, after several generations, the Mongols themselves converted to Islam, spreading the faith across their vast empire.

Three powerful empires rose during the period of consolidation and expansion (1405–1683). Babur, a descendent of Mongol leader Genghis Khan, started taking over India in 1519, founding the Mughal dynasty. At its greatest extent, the Mughal empire covered most of the Indian subcontinent. Mughal ruler Shah Jahan had the Taj Mahal, one of the architectural wonders of the world, built in memory of the favourite of his three wives.

By contrast, the Shi‘ite Safavid dynasty had its origins in a Sufi brotherhood in northwestern Iran. After winning the support of local Turkish tribesmen and other disaffected groups, the Safavids were able to expand throughout Iran and into parts of Iraq.

Meanwhile, in what is now Turkey, the Ottoman Empire was on the march. The Ottoman dynasty, which had started at the turn of the 14th century, conquered lands in the Middle East and in Europe, including Hungary, Serbia, Romania, and Bosnia. In 1453 the Ottomans captured Constantinople from the Byzantine Empire and turned it into the new capital, Istanbul. The Ottoman Empire’s trade ships controlled much of the Mediterranean Sea. The Ottomans had a sophisticated culture and made alliances with European powers such as France and Great Britain. Then, in 1683, the Ottomans reached a limit. In that year, they invaded Austria, penetrating all the way to Vienna, where their ambitious campaign failed. It was a turning point, and a telling marker for the future.

As the Islamic world entered its next phase, reform, dependency, and recovery (1683 to the present), it faced a new challenge—the rising power of Europe.

In the 1800s the British took over India as a colony, finally snuffing out the crumbling Mughal empire. The Ottoman Empire survived longer, but over time it weakened as well. As it did, colonial powers such as France and Britain took control, both directly and indirectly, of more and more territory in Africa, Asia, and the Middle East. Western powers grew increasingly interested in influencing the Middle East when they learned of the vast stores of oil that lay underneath such countries as Iran, Iraq, and Saudi Arabia. Eventually, colonized lands became new countries, in some cases more constructs than organic nations, with arbitrary boundaries and markedly different groups of people suddenly designated as countrymen. Such acts led to many questions about what kind of identity should matter most—national or religious.

As you read this book you will learn much more about the Islamic world. You will have the opportunity to explore the perils and promise of great empires, to discover a profound and diverse cultural heritage, and to learn what unites and separates different branches of the Islamic faith. And you will gain a new perspective on one of the world’s greatest and most enduring religions.