England probably has a 2000-year history of making wine, but the trouble is that it’s an inglorious one – until now. And for the first signs that ‘things can only get better’, we wouldn’t have to go back much more than 20 years to find the first flash of brilliance which would transform a woebegone, unconfident and, frankly, unnecessary English wine world into the thrilling place that it is now – so full of potential that I sometimes call England ‘The Newest New World Wine Nation’.

This Brave New World of English wine is based on bubbles, but the preceding 2000 years were not. Oh, there probably were some wines with a bit of prickle to them, because when the autumn was cold wines couldn’t always finish off their fermentation and when you drank the wine in the following spring, it might have had a bit of a sparkle for a week or two as it finished its fermentation. But that would be chance and in any case was there really much wine being made? Did the Romans plant vines? A few archaeological digs imply they did, but it seems more likely that they imported boatloads of wine from the warmer areas of Europe that were part of their empire rather than struggled to make something decent from the shivering straggly vines they’d manage to grow in Britannia.

And after the Romans came the Dark Ages when the English gave up trying to be civilised for a few centuries and anyway, temperatures appeared to drop so there was even less incentive to try to ripen grapes. I’d sort of expect that drinks like mead would have been popular. This went on until about 1000AD, when things perked up a bit. We entered what the climate experts call ‘the Medieval Warm Phase’, which wasn’t any warmer than in Roman times, but we had a Christian Catholic Church by then, and they needed wine for Mass, presumably red wine, the grapes for which they still would have struggled to grow, in chilly England. And we had a fair number of nobles keen on the finer things of life, many of them descended from the Normans who came over to England with William the Conqueror in 1066. The Domesday Book of 1087 showed that England – mostly London and East Anglia – had just 42 vineyards, few of them larger than an acre or two. Not a lot? Exactly.

You can try as hard as you like but it’s difficult to find much evidence for a flourishing vineyard scene. Anyway, the south-west of France, including Bordeaux, became part of the English Crown in 1152 when Henry II married Eleanor of Aquitaine. A nice Bordeaux rouge? Or a thin sharp Essex white? You wouldn’t choose the Essex white. Even literary references seem to favour chat about red wine – and that wasn’t locally grown.

The ‘Little Ice Age’ wouldn’t have seemed so little at the time. It lasted from about 1400 to about 1850. The River Thames would freeze over, sometimes for up to two months, and frost fairs and markets were held on the ice. There were a few vineyards planted in places like Deepdene and Painshill in Surrey, but they mostly seemed to be rich men’s follies, and, despite the effects of the Industrial Revolution beginning to warm things up a bit after 1850, honestly, not much of interest had happened by the time 1950 came along a century later. Between the First and Second World Wars not a bottle of English or Welsh wine was commercially produced. And it still wasn’t warm.

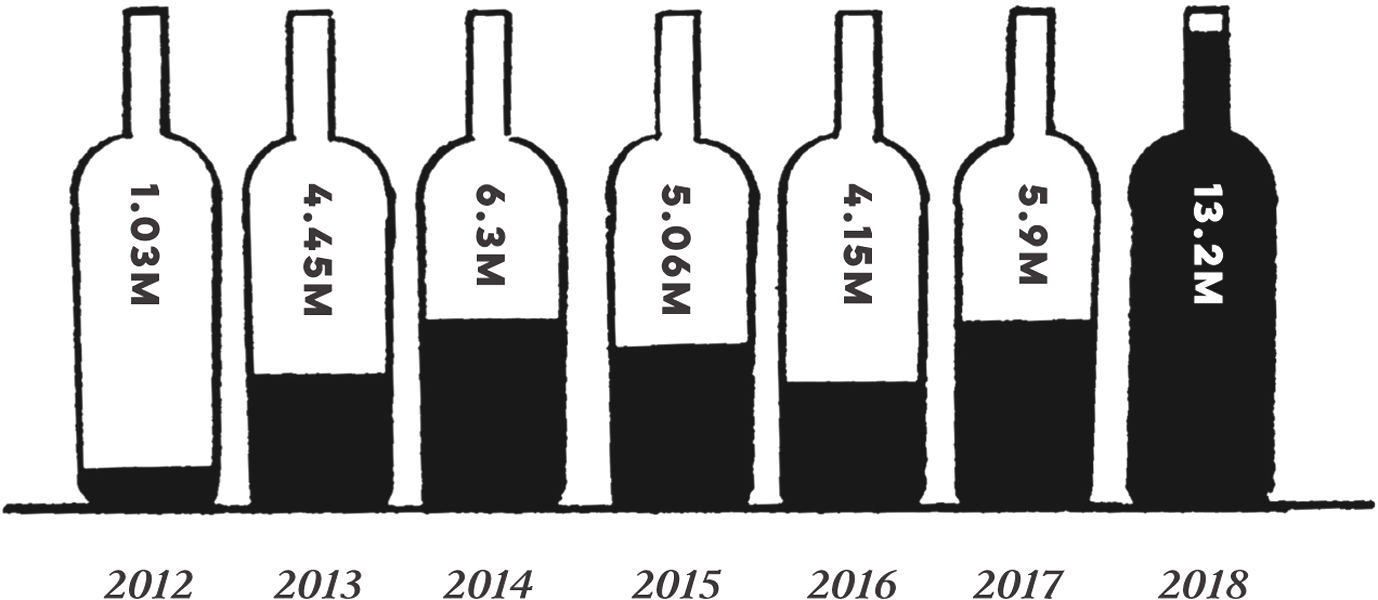

A visionary called Barrington Brock established a viticultural research station at Oxted in Surrey after the Second World War. His vineyards were high up and the weather was usually cold and wet. But over the next 25 years he did at least prove that you could grow vines outdoors in the UK and make wine from them, even though he never managed to turn a profit for himself. Two other pioneers in the 1950s and ’60s – Major-General Sir Guy Salisbury-Jones at Hambledon in Hampshire (now gloriously revived) and Jack Ward at Merrydown in Sussex – also cautiously planted vines and made wine. Not much. Indeed, hardly any. In 1964 the total national crop was recorded as 1500 bottles! (The UK produced 13.2 million bottles in 2018.) But they offered the wine for sale and someone bought it. The first faltering steps toward the modern glittering English wine scene had been taken.

Both Guy Salisbury-Jones and Jack Ward believed in the eventual success of sparkling wine here, but this first revival was on the back of mostly thin, mean whites, often drunk without complaint for fear of offending your host. I had a few and, gosh, they were hard work. I kept hold of a 1976 from Chilsdown near Chichester for 35 years – regularly holding it up to the light to see if its bleach white colour had matured at all. It never had. So in 2011 I cracked it open, and this pale, unfriendly liquid forced its way out, indignant at having been disturbed and as lemon-lipped and cantankerous as it had been at its inception. Proud, unbending – yes. Fun to drink – definitely not.

The wines certainly became more drinkable during the 1980s, because slightly sweet, fruity German wines were all the rage in Britain – at one time half the wine we drank in Britain was German. Several German or German-trained winemakers turned up in England, at such wineries as Lamberhurst, High Weald and Tenterden; they took one look at our vineyards – most of which were full of German, cool climate vine-crossings like Müller-Thurgau – and thought, we know what to do here, make German-style wines. Germans made their wines sweeter by adding some grape juice – full of sugar – which they called Süssreserve. In Germany this usually made for a fairly flat mouthful, but England was cooler than Germany, the acid in our grapes was higher, and so a splash or two of sweetening grape juice merely balanced the acid rather than flattened the wine.

There were a lot of pretty poor wines made in the 1980s, but also some good ones, and you could reasonably say that making English Liebfraumilch-type wines was the first real sign of a new wave. I look at my tasting notes from the 1980s and early ’90s, and find lots of charming, fresh, slightly leafy, slightly grapy white wines coming from wineries such as Staple, Barnsole, Tenterden, Biddenden or Syndale Valley in Kent, Lamberhurst, Carr Taylor, Nutbourne or Breaky Bottom in Sussex, Wootton, Pilton Manor or Three Choirs in the south-west and Pulham St Mary in East Anglia. All nice but none of them world-shattering. None of them doing something unique and better than anybody else. That didn’t happen until the 1990s. You can call this the Second New Wave. You can call it a birth, a rebirth, an apocalypse. I call it ‘The Nyetimber Effect’.

In 1988 a couple of marvellously cussed Americans from Chicago decided that you could make great sparkling wine in an area of England with very similar soils and climate to Champagne, using the same grape varieties as Champagne, and the same methods and top-end equipment as were used in Champagne. All the experts said you couldn’t do it – plant apples like everyone else. But every time someone told Stuart and Sandy Moss they couldn’t turn their gorgeous medieval Sussex estate of Nyetimber into a world-class sparkling wine producer, they became more determined. As Stuart said, they persevered almost because it was so damned hard.

They made their first sparkling wine, out of Chardonnay, in 1992. It won the Trophy for Best English Wine in 1997. They made their second wine, from Chardonnay, Pinot Noir and Pinot Meunier, in 1993. This won the Trophy for Best Sparkling Wine in the World in 1998. I remember the shock, the excitement, the shivering thrilling realisation that I was tasting something entirely new, of astonishing potential, which would change my wine life for ever. Such events don’t come round often in an entire lifetime of wine. I was grateful to be there at the start, and I knew that England had found its vocation as a wine country.

I had already been making speeches about the effects of climate change since the early 1990s – to deaf ears, frankly. But now it all made sense. The Champagne region was only a couple of hours’ drive south of Calais on the English Channel. I had seen reports showing how their soils and many of the soils in southern England were the same. I knew that Champagne traditionally was about 1°C warmer than southern England, and experts said that was the difference between northern France just being able to ripen the classic French grapes, and southern England being unable to do so. Yet Champagne had been warming up all through the 1980s and ’90s. Champagne in the growing season at the end of the 1990s was 1°C warmer than it had been a generation before. And if so, was southern England still only 1°C cooler than Champagne? Didn’t that mean that by the 1990s, Kent and Sussex were just warm enough to ripen Chardonnay and Pinot Noir – and if someone took the plunge, could these chalky and sandy soils of England’s south-east be a new Champagne?

So thank you to the Mosses and thank you Nyetimber. There really was a ‘Nyetimber Effect’. It really did transform English wine. Nyetimber aimed for the very top of one particular quality pyramid, the sparkling wines of Champagne, which had been unchallenged in the world for several hundreds of years. Now there was a challenger – just over the English Channel. Nyetimber weren’t the first to make fizz in England and to believe in its future. The really early pioneers of the 1950s made a tiny bit. Carr Taylor made some from Sussex Reichensteiner in 1983 and it was quite good. New Hall actually made a little Pinot Noir fizz in 1985 – but these were merely ripples. Who would take the big plunge? Nyetimber, with its wonderfully ‘can-do’ American owners who simply would not be denied.

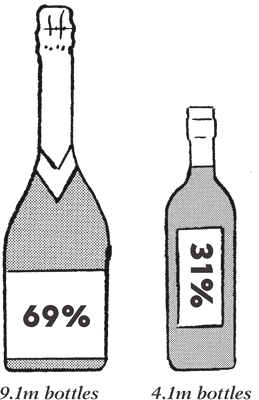

Of course, there continues to be a lot of still wine being made in the UK, but we are increasingly seen by the rest of the world as sparkling specialists. About 70 per cent of our wine is sparkling, and every year the percentage of grapes being grown for fizz increases. But Britain is lucky in several ways. Champagne hardly makes any still wine – it lives or dies by its expensive sparkling wine and its hard-won reputation. As Britain sets out to share this sparkling glory, with all the investment and long-term planning that requires, still wines – cheaper to make, cheaper to sell – provide a crucial cash flow safety valve. While new plantings career onward and upward, as they have done since 2017, still wines actually offer one of the few channels, along with wine tourism and hospitality, to get some money coming back into the business.

(shown in millions of bottles)

This shows that production is still erratic in the UK, but the direction will be relentlessly upward as new vines come on stream.

But the spirit is a sparkling spirit. Ridgeview quickly joined Nyetimber in the 1990s as a winery solely concerned with making top Champagne-style fizz. Chapel Down, the winery now occupying the old Tenterden site, is a major fizz producer, and almost all the new tyros are focused on fizz – Gusbourne, Coates & Seely, Hattingley Valley, Hambledon, Exton Park, Greyfriars, Rathfinny, Harrow & Hope, Furleigh and Simpsons – many of them make some still wine but all of them concentrate on fizz. And did I mention Taittinger and Vranken-Pommery? They are two leading Champagne producers. They have both established estates – in Kent and Hampshire respectively – with the objective of making some of the best sparkling wine in the world. They won’t be the last ones to cross the Channel.

Honestly, if you had to choose a nation in which to grow vines solely based on its geology and soils, Britain – England, Wales and even Scotland – would be hard to beat. So why haven’t we had a thriving wine culture for the last few hundred years? Well, for those of us who live here – the weather. The Roman writer Tacitus dismissed Britain as a filthy, foggy, rainy hellhole 2000 years ago. What? England? The south and east of England? In the 21st century? Filthy, foggy and rainy? I don’t think so. In fact, millennials, and those even younger, could be excused for not recognising this view of the British Isles at all. People who grew up in the 1950s, ’60s, ’70s and ’80s – ah, yes, they remember the fogs, the drizzle, the certainty that August Bank Holidays would be miserable. Do older people always look back and say things were different then? Yes, they were. They were worse.

Climate change and global warming are probably the biggest challenges the human race faces today. In most parts of the world, the effects of climate are already worrying and will probably become catastrophic. There are just a few corners of the globe where climate change is having a positive effect. And if I had to choose one place where climate change has completely transformed a way of life for the better, it would be in the vineyards of England and Wales. That transformation isn’t without its challenges.

But let’s have a closer look at this new British climate which promises so much.

First, and most important, it is warmer. It’s warmer in Cornwall. It’s warmer in Sussex and Kent. It’s warmer in Essex and Norfolk, and Monmouth and Conwy and even Yorkshire, for goodness sake. Which means that grapes will ripen in areas they never would before, and that varieties like Chardonnay and Pinot Noir, which need more warmth than England has had for 2000 years, are now the dominant varieties in our southern vineyards and performing superbly. But how is it warmer? Well, there’s no question that we have been getting considerably more very hot days in our summers. Very hot for Britain I would describe as 30°C and more. In the last couple of decades of the 20th century, many years would pass with not a single day reaching 30°C. In the first 20 years of the 21st century, only 2007 saw a summer with no days at 30°C, although the average temperature for the whole of 2007 was the second highest on record.

And this heat is extending back into spring and forward into autumn. Record heat is being recorded in June, May and April, let alone March and even February (I have more than once recently sat outside my local pub with a pint in February – in shirtsleeves). August’s heat is stretching into September (in 2019 they were still recording unheard-of temperatures as high as 33°C in south-east England at the end of August: on the Bank Holiday for a start). September now rates as late summer, and frankly October often does as well. Three of the five warmest ever Septembers have been in this century, and nine of the ten hottest Octobers have been in the last 20 years. Put this together with much more professional vineyard management and you have vineyard owners boasting that they are picking grapes with twice as much sugar as a generation ago, and the harvests are up to a month earlier. In 2018 the English harvest started on August 28.

But this astonishing change in our summer weather is not an isolated phenomenon. We are surrounded by various weather systems in Britain as a maritime nation. They are becoming more extreme, too. In particular, as the systems to the west warm up, and the south-westerly is the prevailing wind for the majority of our vineyards, we get more rain events, much stronger winds and greater likelihood of things like flash flooding, torrential downpours and hail. Often we see a localised area getting several months’ worth of rain falling in a single day.

Imagine if your vineyard is in the middle of one such area. Periods of great heat can often bring a much more violent reaction of storms, and even cold (look how the weather went from very hot to very cold at least twice in the summer of 2019, during June and during August – after which, of course, record heat was once more recorded). This climate change phenomenon is a roller coaster ride. Few experts any longer simply refer to it as ‘global warming’ and many actually call it ‘climate chaos’. And they’re not wrong. Nothing is predictable any more. At the moment Britain’s vineyards are on an upward curve. Let’s make the most of it while we can.

And there’s one more thing. Frost, especially springtime frost. Again, this isn’t just a British phenomenon. Europe is increasingly being hit by vicious late spring frosts. Famous vineyard areas like Burgundy in France have been hammered again and again in the 2010s. If you have a cold winter and the vines are late to wake and start their growing season, with rising sap and buds being pushed out, a spring frost may well do no harm – the vine’s branches can cope with all but the worst frosts at way below 0°C. But if you have a warm February and March, as we now often do, then by mid-April those buds may well be pushing out and opening up, encouraged by the sun. So a frost that might have been harmlessly rebuffed by tough vine wood can devastate the delicate vine buds and decimate your crop.

On April 26 and 27 2017, a terrifying frost destroyed crops all over Europe. Southern England’s lovely warm March and early April weather had encouraged the vines to push out their buds. Overnight temperatures as low as –7°C meant many vineyards lost up to 80 per cent of their crop. So much for global warming.

They say that the most important factor when it comes to selling a house is location, location, location. In a marginal vineyard country like Britain, the coolest of any of the serious wine-producing nations, suitability of your vineyard site must be at the top of your list of priorities. Well, you’d think so. But an amazing number of British vineyards in the second half of the 20th century were planted simply because the piece of land concerned was available. Often it was part of a property owned by a family who thought the idea of a vineyard was a lovely one, especially after a series of delightful summer holidays in places like France.

Often it was a patch of farmland that wasn’t being used for much, so why not try vines? And often the plot chosen was on heavy, wet, cold clay soils of the sort that England is full of, and if there is one thing vines don’t like it’s having cold wet feet. They don’t much like sitting there in the teeth of a gale either, and many early sites were completely exposed to the elements. And vines do like a fair bit of sun, so those early sites which were north facing were hardly likely to give you a decent drop of remotely tasty wine.

England is brilliantly furnished with good to great vineyard soils which drain well and offer the vines the nutrients they like. One world vineyard authority, Dr Richard Smart, says that the Paris Basin is the motherlode of all vineyard land. So what is the Paris Basin? It’s the ring of chalk and limestone ridges that run around Paris. It passes through Champagne and then it moves north from Calais across the Channel to the cliffs of Dover and England. In southern England it includes the North and South Downs. The chalk also extends right up through the Chiltern Hills to Hertfordshire, Cambridge, Norfolk, Lincolnshire and East Yorkshire. Jurassic limestones spread from Dorset up through the Cotswolds and on into Lincolnshire and northern Yorkshire. This pale soil is very well drained and reflects heat back onto the grapes. Sounds perfect.

Hampshire is all about chalk and this view of cellar excavation at Exton Park shows there is almost no topsoil at all.

And this is just the chalk and limestone-based soils. The Thames Valley and elsewhere also have warm, well-drained gravel beds great for vines. The greensands and sandy clays that keep popping up in Kent and Sussex and elsewhere are warm and well-drained and highly suitable for vines. Another great climate expert, Dr Alistair Nesbitt, reckons there are well over 30,000 hectares (74,100 acres) of prime vineyard land available in England – and barely any of that has been planted yet, even by estates which are situated on the chalks, the limestones and the greensands.

And there are all the other soils. The most common of these in southern England is clay, for example Wealden clay or London clay. Clays mixed with limestone, gravel or sand can make excellent vineyard soils. Pure clay is much more difficult. Tough, thick, claggy clay is cold and waterlogged in winter and wet weather, and cracked and parched in drought. It doesn’t sound promising, yet, especially in Kent and Essex, delicious wines are being made from grapes grown on the clays, even including what are often England’s best Pinot Noirs and Bacchus. How? Well, this is where good old climate change and local weather go hand in hand. Essex is the driest part of England. Suffolk, Norfolk and Kent do pretty well, too. And there are an increasing number of places like the Crouch Valley in Essex which are proving to have amazingly suitable local climates. It’s rarely going to be drought-dry there, so the clays are just warm enough, not too damp, and delightfully soft, scented red and white wines are possible. On heavy clays that shouldn’t be possible. In Europe it normally isn’t. Somehow it can work in England, and above all, in Essex.

And as the climate warms, even regions like Scotland and the Welsh borders are revealing soils that are pretty much the same as those in Germany’s Mosel Valley, France’s Beaujolais and northern Rhône Valley, and Portugal’s Douro Valley. Dr Richard Selley, a greatly respected British geologist – and wine enthusiast – put together a scenario of vineyards in Britain based on widely accepted projections of temperature increases up to 2080. The Thames Valley and Hampshire could be too hot for wine grapes; our best Chardonnay and Pinot Noir could be coming from the uplands of Derbyshire and Yorkshire, and refreshing whites could be made on the banks of Loch Ness.

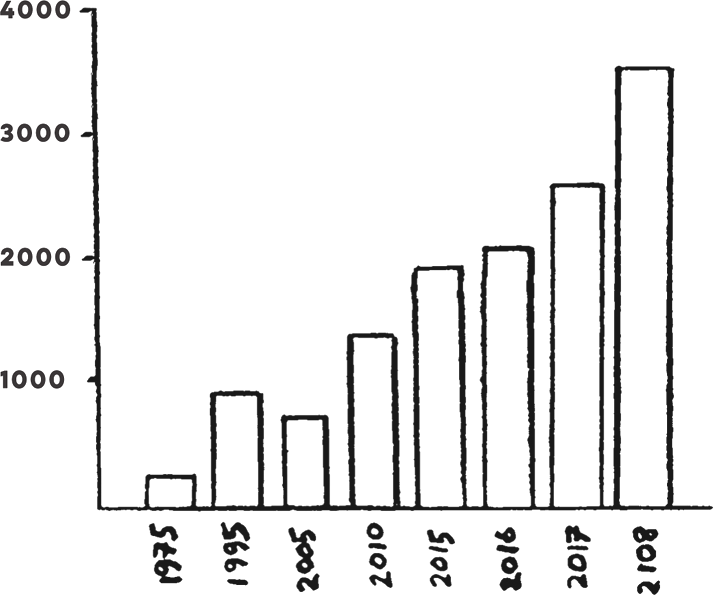

Vineyards are cropping up in increasing numbers all over England and Wales, from Yorkshire down to Cornwall, but the biggest concentration is in the drier and warmer areas of East Anglia and the South-East.

Britain’s leading vineyard expert, Stephen Skelton, thinks that the soil is less important than the site being protected from the worst of the wind and rain, and being well exposed to the heat of the sun. There has been a rush during the 2010s to plant the chalky downland of southern England because the soils seem identical to many of those in Champagne, and global warming has meant that the climate is now fairly similar, especially in many parts of Kent, Sussex and Hampshire, to what it was like in Champagne at the end of the last century. So this change has been rapid and has had a significant effect on what types of site can now be successfully planted. The rule used to be that anything over 100 metres (330 feet) high wouldn’t ripen grapes. It will now and there are vineyards at 200 metres (660 feet) high that are producing crops of good grapes. Many of these are on chalky sites.

Even so, they will generally get more wind than lower sites and that is a mixed blessing. Breezes are generally welcome in the summer and autumn because they keep the air moving and stop fungal infections from taking root. But strong winds lower the temperature, blow the flowers off the vines so they don’t set a crop, and can even break the branches of young vines. You see a lot of windbreaks in British vineyards, usually in the south-west, to catch the worst of the gales. Sometimes even they are not enough.

Airflow can also help in preventing frost. Many sites have frost pockets in them where cold air drains and sits, freezing any vines that may be planted there. Keeping the air moving is the best way to combat frost, and various systems can be employed against frost, all of which rely upon trying to keep warmer air moving into colder spots. Chapel Down’s Kit’s Coty vineyard in Kent probably has the best system. The high speed Eurostar trains hurtle past the bottom of the vineyard several times an hour, at 200 kilometres (124 miles) an hour – wonderful for keeping the air constantly on the move.

And whether you’re on a slope or not matters, too. In a cold climate like Britain’s you want to catch as much of the sun as possible. Slopes, generally, do this best. Although in midsummer there isn’t much difference in the amount of sun a flat or a sloping vineyard gets, as the season wears on and the sun drops lower in the sky, a vineyard facing south and planted on a slope of 30° will get far more direct sunlight. By October such a site may be getting 30 per cent more sunlight than a flat site. Most new vineyards are sited on slopes, although rarely as steep as 30°. Usually the objective is to have a southerly aspect toward the sun. Some growers prefer south-easterly so that the vines warm up more quickly in the morning. Some prefer south-westerly, since typically afternoon sun is warmer than morning sun. Surely no one would want to face north? Well, Peter Hall at Breaky Bottom in Sussex has a north-facing vineyard that always ripens before its southerly neighbour. Robb Merchant at White Castle in Wales has just planted a northerly slope, but he shows me the path of the sun, the wind protection from a copse of trees, the rain shadow from the local mountain, and he reckons he’ll be able to ripen Cabernet Franc on it, something no one else has managed yet in Wales. And surely New Hall in Essex know everything about their local conditions after 50 years of growing some of England’s best grapes? Their new vineyard below the tranquil Purleigh churchyard looks to have a fair bit of north-facing land to me.

Critical mass really does matter. And success breeds success. And a few really hot summers in Britain turn people’s heads and fill their minds with dreams of owning a vineyard more than anything. 1976 was a spectacularly hot summer – I spent it acting on the melting tarmac streets of inner Manchester – I should know. Despite the summer coming to an abrupt halt at the end of August and two months of gloomy, drizzly English miserableness ensuing, there was a rush of interest in establishing vineyards across the UK, and some of the nation’s most impressive vineyards were planted in the aftermath. They didn’t all prosper, and despite the 1990s bringing some of the warmest ever British weather, including some decent autumns, there was a drop of more than a fifth in the vineyards’ acreage leading up to 2003.

Ah yes, 2003. This was the year, far more than 1976, when people began to wake up to the fact that we are living in a warming world. Temperatures reached 35°C for the first time since records began nearly 400 hundred years ago. 35°C? Faversham in Kent reached 38.5°C on August 10. A big intake of breath, and then a renewed enthusiasm for vineyards, which saw them increase by about 20 per cent in 2006 alone. Since then warm winters, springs, summers and autumns have continued to fuel the belief that England’s time has come and maybe Wales’s, too.

And the proof is in the pudding. Beginning this modern era with the glorious wines of Nyetimber and Ridgeview at the turn of the century, a whole swathe of the 21st-century plantations are producing wines – generally sparkling – that seem to improve with every vintage. Nyetimber and Ridgeview are still there, stronger than ever, but there’s an ever-growing jostling band of pretenders whose wines can equal theirs. Success breeds success. Critical mass matters. In 2017 a million vines were planted. In 2018 a million and a half vines went into the ground as the vines that were already there produced a harvest of 13.2 million bottles to eclipse the previous largest crop of 6.3 million bottles in 2014. Which spurred everyone on even further. At least 3 million vines were planted in 2019, maybe a lot more, as weather records tumbled once again, and several new ‘hottest ever’ days were recorded. Vineyard Number 9321 is one of the UK’s newest registered vineyards – it’s only two vines, in Upper Lodge’s kitchen garden in Sussex – but from small acorns .... And where are most of the new plantings? On the soils and slopes that have proved themselves in the last decade. On the chalks of the North and South Downs, on the greensands and sandy clays of Sussex and Kent, in the protected calm of the East Anglia coast.

The heat of 2003 had an effect across the Channel, too. Champagne’s reputation for the finest fizz in the world has relied on a regular supply of grapes creeping to ripeness in fairly marginal conditions. 2003 in Champagne produced their earliest harvest ever in blistering weather after a blistering summer. A lot of producers thought they would simply be unable to make proper sparkling wine – and if this was a sign of the future, they’d need to think about finding somewhere cooler to produce their grapes. You didn’t have to be a genius to realise that the most suitable soils and climate were just over the Channel in southern England.

After a bumpy start, British vineyards are rapidly expanding, with most of the plantings being of the Champagne varieties: Chardonnay, Pinot Noir and Pinot Meunier.

I first became aware of the French interest when I started getting telephone calls in 2004 asking me to confirm this or that rumour that the big Champagne houses had moved in on Kent under hidden identities and bought large swathes of chalky, infertile, low value agricultural land. Low value if you’re thinking of raising a crop of wheat. Remarkably high value if you’re a Champagne producer looking for a safety net. The price of a hectare of Kentish chalky farmland was about 1 per cent of the price of good vineyard land in Champagne. These were only rumours, but I still look at swathes of Kentish land that I should have expected someone to start developing into vineyards ages ago – and it’s just sitting there. Have the Champagne houses already land-banked large chunks of England for the time when they are forced to look elsewhere for their supply of grapes? But it wasn’t just rumours. In 2005 my dentist told me of a French friend of his, Didier Pierson, a grower from Avize, one of Champagne’s best villages, who had planted a vineyard on a high, chalky ridge in Hampshire. In 2007 and 2008, as I was touring various vineyards in the south, I couldn’t resist asking – have the Champagne boys tried to buy you yet? Every vineyard I went to had had a visit, some had had an offer but none had said yes – yet.

And then in 2015 the fox broke cover. Taittinger, one of Champagne’s greatest houses, announced that they had purchased an old apple orchard on chalky soil near Canterbury in Kent, and they were planting the Champagne grape varieties – 20 hectares (50 acres) in 2017, another 8 hectares (20 acres) in 2019, with more to come. Their first crop was in 2018. I know where the wine is being stored, but I haven’t had the audacity to ask to taste it. After all, Taittinger will want to make a big splash as they launch their first wine under the Domaine Evremond label (Charles de Saint-Evremond was an exiled French nobleman who performed wonders in encouraging Champagne drinking in England in the 17th century).

And they shouldn’t tarry too long. Vranken-Pommery, another famous Champagne house, has bought an estate on the Hampshire chalky downlands near Exton Park. They had planted over 40 hectares (100 acres) by 2019 and have been burnishing their skills by already producing some sparkling wine called Louis Pommery England at a neighbouring winery, Hattingley Valley. The years of 2018 and 2019 were very hot in France. Will more Champagne houses bow to the inevitable and set up stall in the UK?

The increasing interest of the French in English vineyards can only be a good thing for improving the reputation of the nation’s wines, but it makes me wonder a little about whether an ever-increasing French and, maybe, other European presence in the UK, will bring about pressure to adopt European bureaucratic controls for British wines. Europe has a very tightly regulated and, frankly, restrictive appellation system for controlling places where you can grow vines, which varieties you can grow and what types of wine you can make. There is also a looser system of control for areas without much tradition or for grape varieties that are not usually grown there. In France we’d know these wines most frequently as Vin de Pays. So there’s a straitjacket approach and there’s a laissez-faire ‘anything goes’ approach. All the greatest traditional wines of Europe are made inside the appellation straitjacket. But the majority of the most exciting, imaginative New Wave, and often affordable, wines are made under the very broad umbrella of the laissez-faire.

Well, France has had 1000 years to figure out what brings the best results, so maybe it deserves to be able to lay down the law about what works best in certain regions and, I suppose, put a bit of a straitjacket around it. But Britain has no tradition of excellence at all. To be honest, everything is wonderfully experimental. We’ve got ideas as to what vineyard sites might work best. We’ve gone headlong into planting the Champagne varieties while keeping loads of other less trendy varieties in the soil. We think we know what’s best for each of us, but we don’t know. In this way, we are a new frontier, New World wine country with everything to prove, everything to explore. There are quality systems in place in the UK, but they are far less restrictive than those in France, and all the better for it. Any system which bureaucratically attempts to shackle our enthusiasm and our imagination can’t be a good thing. We don’t yet know what will excel, where, and how. But there is an impressive bunch of wine entrepreneurs determined to find out, and they don’t need any help from the authorities.

Britain uses the European indicators of quality and authenticity in terms of regional original or traditional production – the PDO or Protected Designation of Origin and the looser term, PGI or Protected Geographical Indication. Many European wine producers, for example in France, Spain and Italy, use PGI when they are looking to make wines which don’t conform to tradition. In Britain PGI is used widely because it has fewer restrictions.

People have also started talking about ‘Grand Cru’ vineyards. Grand Cru means ‘great growth or ‘great site’. The very best wines in Burgundy come from a very few great sites that have earned their spurs over 1000 years. Bordeaux has a few such properties famous for hundreds of years. The Loire Valley, Alsace, Champagne, they’ve all worked out their special sites and accorded them ‘Grand Cru’ status. And now we are talking that language in Britain. People are calling Kit’s Coty in Kent a ‘Grand Cru’, but it’s only made a handful of vintages, impressive though they are. Gusbourne talk about developing a Grand Cru in their vineyards down by the Romney Marsh. Is the Tillington site near Petworth in Sussex a Grand Cru for Nyetimber? Will Denbies’ south-facing, 40 per cent slope be Surrey’s finest? We don’t know. It’s far too early to say. And with climate change accelerating, the probability is that the real ‘Grand Cru’ sites aren’t even planted yet. There are a series of south-facing, protected horseshoe bowls in the South Downs – Wiston Estate has one and it might even have several. I look at them and say – wow, let’s dream of ‘Great Sites’, let’s seek them out and try to draw out the magic they may possess. But let’s not make ‘Grand Cru’ a legal entity – if it’s good enough, wine lovers will recognise it for what it is without any help from lawmakers.

Wine comes in dozens of different styles – from still white and red to varying degrees of pink, from orange, through sweet and fortified to sparkling. The tiny wine industry of England has come of age and produces world-class wines, especially fizz, which is now the most important category in England, but what about the still wines? They’re still incredibly important and with the phenomenal expansion of vineyards may well become more important in the future – still wines are cheaper to make, quicker to bring to market and crucial for the winery’s cash flow.

In the following pages I’ve outlined the styles, both sparkling and still, that are important for English and Welsh wine.

(shown in millions of bottles, 2018)

Sparkling wine now easily outpaces still wine in Britain, as traditional-method fizz begins to earn a worldwide reputation for quality.

It is quite remarkable how Britain has gone from being a still white wine producer of declining relevancy in the world of wine to being a contender for the title of world’s best sparkling wine producer – all in the space of a generation. Frequently nowadays we wine critics have to remind ourselves that still wine is important in Britain and that it has never been better, at the same time as more and more examples of fizz that are good to outstanding appear with every vintage, and awesome amounts of land get planted with vines each year – most of them with the three Champagne varieties, Chardonnay, Pinot Noir and Pinot Meunier, which now comprise 70 per cent of all the vines planted. And the objective is always to make sparkling wine, not still wine. No one has yet set out to make the world’s greatest red Pinot Noir or white Chardonnay in Britain but quite a few people have set out to make the world’s greatest sparkler.

This ambition is firmly rooted in making wines from the Champagne varieties in the same way as they produce them in Champagne. By inducing a second fermentation inside the sealed bottle, capturing the bubbles that fermentation produces. Most of the wines of Champagne are made from a blend of all three Champagne grapes, so that a typical ‘Classic Cuvée’ would probably have at least half of the base wine coming from the black Pinot grapes, pressed extremely carefully to avoid staining the juice red. The rest of the juice would be Chardonnay. This ‘Classic Cuvée’ is definitely the most popular style in Britain, too.

Initially, during the 1990s and 2000s, these wines would all be vintage-dated, from a single harvest. But the unpredictable nature of the British weather – particularly the uncertainty as to what kind of quantity of grapes the vines can produce – has meant that, just as in Champagne, more and more wineries are now making a non-vintage style using wines from more than one harvest – or, as Nyetimber, puts it, a ‘multi-vintage’ style. Several of the larger wineries such as Nyetimber, Hattingley Valley and Chapel Down, as well as smaller ones such as Exton Park, put a considerable percentage of their wine each harvest into a reserve. This reserve wine ages and softens and deepens in flavour and can then be added back into a blend of younger wines to achieve a balanced and consistent style which simply isn’t possible with wines based on one vintage only.

Most English sparkling wine producers started out making vintage wine, with that year stated on the label, but most now produce both vintage and non-vintage. Vintage wine comes from a single harvest whereas non-vintage and multi-vintage wines are a blend of harvests. These require reserve wines to be put aside each vintage for later blending to soften and improve the flavours and to achieve consistency year on year. Since so many sparkling wine producers in England are recently established, reserve stocks have been low but each year should add to the stocks available and large vintages like 2018 and ’19 will provide the perfect opportunity for wineries to build up their reserve stocks – so long as they have enough storage tanks. Luxury cuvées are special releases, using the best grapes and the best selection of base wines, often with barrel ageing and extended time in bottle on the lees. Some of these wines are superb but you pay for the privilege. If you want to see what they are all about, try the following: Chapel Down’s Kit’s Coty Coeur de Cuvée, Coates & Seely’s La Perfide or Hattingley Valley’s King’s Cuvee.

The very first Nyetimber wine to achieve renown was a Blanc de Blancs, made only from Chardonnay grapes. This is one of the most popular – and highest-priced – styles of wine made in Champagne, and it looks as though this trend will be followed in Britain, too. The best Chardonnay grapes in Champagne come from one very chalky region called the Côte des Blancs, the White Slope. Nyetimber’s 1992 actually came from sandy soils, and many of the best English Blanc de Blancs wines until about 2010 came from clay and sandy soils. Since then there has been a rush to plant southern England’s plentiful chalk slopes with, above all, Chardonnay and more of these ‘white grape only’ sparklers do now come from chalky vineyards. There’s no doubt that these have an arresting, focused, limpid quality and an acidity that sweeps across your tongue. The wines from grapes grown on clay and sand are generally rounder, softer, creamier, nuttier. Neither is better or worse, just gloriously different. And many top Blanc de Blancs wines will mix grapes from chalk with non-chalk grapes.

Blanc de Noirs is a less popular, but equally impressive style of wine made only from black (noir) grapes – in almost every case, Pinot Noir with or without some Pinot Meunier. These wines are fuller, broader, a little richer on the palate, the acidity isn’t quite so taut, the texture isn’t quite so lacy. But England is producing tremendous examples, even if producers find them more difficult to sell. That means they may be a bit cheaper to buy, remember. Quite a bit of the best Pinot fruit is grown on clay, some on greensands and sandy clays, but also some on chalk. We are at such an early stage in our development as a great sparkling wine producer that we’re all still experimenting.

If Blanc de Noirs whites are a difficult sell, frothy pink wines may be the easiest sell of all. Pink is right in vogue at the moment, and Britain does it very well. The wines hold onto their pinging English acidity, but wrap this with a fruit of pink strawberry, maybe cherry, maybe pink apple and cream. And these pink wines are not just made from black grapes. Many of the best have a significant amount of Chardonnay in them. Oh, and there are some sparkling reds, too. Not many, but a throatful of Ancre Hill’s Triomphe Perlant – purple red, packed with rough black plum and sloe fruit rudely scented with balsam with a restraining collar of staining foam – should convince you.

Traditionally Champagne has contained a certain amount of sugar or ‘dosage’ to balance the acidity and accentuate the fruit. Not much sugar, in fact you only really notice it when it’s not there. There has been a trend for making bone-dry or Extra Brut Champagne – Champagnes labelled Brut nature, Pas dosé or Dosage zéro contain no sugar at all – and many of these wines make you realise how barely ripe the grapes were that made the wine. A little sugar helps. In England, the acidity in the grapes is generally higher than in France, but in a brilliantly piercing way. There are a few English wines with no sugar at all, and they are impressive though not always lovely. Just a few grams of sugar per litre – the magic figure seems to be somewhere between 6 and 9 grams (in Champagne these wines are labelled as Brut) – seems to me to create the perfect balance in English fizz and it’s not really noticeable until you take it away. When the label says Dry or Brut you will get the proper sensation of a dry wine.

I’ve been talking about sparkling wines made in the expensive and time-consuming Champagne or ‘traditional’ method. This is how all the best examples are made. And in fact 99 per cent of English sparkling wine is made this way. However, there are some wines made by the cheaper ‘tank’ or Charmat method, a more industrial process which is banned in Champagne. Producers like Flint in Norfolk have shown that you can make tasty stuff in this way. The bubble is not quite so fine and long-lasting, but so long as you’re not trying to create the so-called classic Champagne flavours of croissant, hazelnuts and crème fraîche, which rely on long ageing of the wine sitting in its bottle in contact with yeast lees, then the commercial reasons for it make sense. Grapes like Bacchus, Reichensteiner, maybe Solaris, maybe Rondo, which don’t in any case pick up those creamy, nutty flavours, are quite well suited to the Charmat method. And you can release the wine younger and sell it for less than the traditional method wines. We haven’t seen much Charmat method yet. Big vintages like 2018 will mean we’ll see a lot more.

There’s one even cheaper way to make wine froth a bit – you can simply carbonate it. Some of the worst sparkling wines in the world are made like this. Yet they can be a good drink, especially if the base wine is from a very well-flavoured grape variety. New Zealand makes some carbonated Sauvignon Blanc that tastes like – well, fizzy Sauvignon Blanc. Some people say Bacchus is Britain’s answer to Kiwi Sauvignon. Maybe. Certainly, Chapel Down has started making carbonated Bacchus and it tastes like – well, a very easy-going, frothy Bacchus.

It’s not often you find yourself saying thank goodness for Liebfraumilch. But it was the German style of fruity, slightly sweet white wines which gave British vineyards their first cautious wine boom. When the modern wine era began in the 1950s, any kind of template for style was likely to be French and consequently dry. That’s OK if you have ripe grapes, but England in the 1950s and ’60s, and frankly the ’70s and ’80s, didn’t have properly ripe grapes. I’ve tasted a few of the dry whites made in the 1950s and ’60s and, honestly, you couldn’t finish a glass, let alone a bottle.

In the 1980s German wine, fruity, slightly sweet, became the most popular style of wine in Britain. The arrival of several German, or German-trained, winemakers in England who knew how to turn English grapes into a sort of Liebfraumilch meant that home-grown grapes, low in natural ripeness but dollied up with added sugar and the sweetly fruity unfermented grape juice known as ‘Süssreserve’, or ‘sweet reserve’, could make a reasonably attractive, vaguely grapey, sometimes scented, but rarely dry, white wine. But the 1990s were brutal to this rather neuralgic me-too Germanic style. Australian, Californian and New Zealand wines hit the UK market – ripe, alcoholic, sunny but dry. There was no way that England’s home brew could match any of these, and wineries and vineyards began to go out of business.

And if it weren’t for the carnival cavalcade of fizz that Nyetimber and Ridgeview lit the flame for in the 1990s, I can’t see that we’d have that much to celebrate in English wine right now. Sparkling wine massively upped the ambitions of English winemakers. Helped by climate change, but also by far better vineyard management brought into play by the usually well-financed and sophisticated sparkling mob, the old varieties which used to make Germanic styles, but also the queen of whites – Chardonnay – could achieve a ripeness level that didn’t need you to add any sugar to the wine. The new goal is to make great Chardonnay, but the legacy grapes like Seyval Blanc, Ortega and, above all, Bacchus can now ripen well enough to make wines that don’t need extra sugar, and can, I suppose, be likened to New Zealand Sauvignon Blanc.

Medium and medium sweet wines are pretty out of fashion nowadays. But they are a very attractive style when your grapes are high in acidity. Too much acidity makes a dry wine raw and harsh. But if you leave some sweetness in the wine, it balances the flavour to such an extent that the acid can merely seem like a squirt of lime or lemon juice, freshening up the fruit, and the sweetness becomes barely noticeable. In cold countries it’s often not possible to ripen grapes enough to lower their acidity to easy-going levels. Britain is getting warmer, but as viticulture stretches northward toward Yorkshire and westward into Wales many vineyards struggle to reduce the acid in their grapes. In which case, medium styles make absolute sense. Grape varieties like Solaris and Orion are often made with sweetness remaining, and are much better for it. Varieties like Huxelrebe and Siegerrebe aren’t common but make attractive, sappy, zingy medium styles. And even Bacchus is often made with quite a few grams of sweetness left in the wine – but this balances the acid very attractively, and we’d never know we were drinking a medium wine.

There are two ways to make a naturally sweet wine – one that isn’t fortified with spirit as with port. If your grapes are attacked by a particular fungus called ‘noble rot’, which intensifies the sugar without turning the juice into vinegar, you can make great sweet wine. Sauternes from the Bordeaux region of south-west France is the most famous example. Or you can leave the grapes to freeze on the vine and press off the thick, sugary goo while the water is still frozen as ice. Canada, not surprisingly, is famous for its icewine.

Neither of these styles of sweet wine is common in Britain. You need very ripe grapes in the first place for the noble rot fungus to strike your crop, rather than all the other unwanted types of rot. In the old days this occasionally happened by mistake, but apart from Denbies, who have a plot of Ortega that gets hit by noble rot almost every year, few wineries attempt it. Our winters aren’t cold enough for icewine either, but you can, quite legally, pick your grapes, freeze them and then press off the thick sweet sludge and make quite exciting sweet wine. There are a few tasty examples – Eglantine in Lincolnshire probably did it first, but Hattingley Valley in Hampshire also excel. But this style of wine will never be more than a niche movement – something to keep the winemaker excited. Or will it? These wines sell out pretty fast at the cellar door, though it’s difficult to persuade any retailers to stock them.

I really didn’t think I would be including this interesting but challenging category in a book on English wines – this style of wine originated in Georgia 8000 years ago. The wines are made from white grapes and the colour can be orange but doesn’t have to be. But then I tasted Chapel Down’s version in 2015 and another from Litmus Wines at Denbies. These were both remarkably refined, almost delicate, yet unmistakeably made by leaving the skins in contact with the grape juice for far longer than is usual in white winemaking. Just long enough to pick up colour, to pick up a little teasing, tannic bitterness, and a little perfume and flavour which you wouldn’t normally get in a white wine – something like tamarind peel, dusty peach or apricot skins, and apple core. I should also mention the chewy, dusty-tasting Trevibban Mill Orion orange wine from Cornwall. As I said, teasing, but not overdone like many other European ‘orange’ wines are.

In 2019 I had a good look at the wines from organic and biodynamic pioneers like Albury in Surrey, Davenport in Sussex and Ancre Hill in Monmouth and the fascinating, self-confident, almost exuberant wines from radical newbie Tillingham in Sussex. And to my surprise and delight, I thought – we can do organic and biodynamic in this country, too, this supposedly damp maritime nation of ours. We don’t have to use all the chemicals, we don’t have to protect our wines with cultured yeasts, stainless steel and sulphur. We can if we want. But there’s a fascinating ‘natural’, non-chemical future just beginning to stretch its wings. I bet there will be more along soon.

Pink, or rosé, wines will be one of the most important styles made in Britain over the next 10 to 20 years. They should be much more important now, but even in 2019 I was disappointed with the range available, and surprised at how many I tasted lacked real style. However, the standard is better now than it was, and there are more of them. In the 1990s I would do big tastings of English wines, sometimes over 100 at a time, and pink wines were regularly outnumbered by the fairly feeble and scanty reds.

That was understandable in the 1990s because pink wine wasn’t fashionable, as it is now. And you can make delicious, mouthwatering pink out of your red grapes when they don’t ripen fully, which is often the case in a typical English summer. Rondo, Regent and Dornfelder are varieties all making tasty pink wines and they’re often better than reds made from the same vineyard. But it is Pinot Noir and Pinot Meunier which will provide the grapes for Britain’s best pinks in the coming years as plantings of these two have exploded to provide the base wines for sparkling wine. These varieties both make excellent pink wine, either sparkling or still, and many vineyards will realise it makes very good business sense to release a still pink wine at nine months old rather than waiting three years to release the same base wine as a sparkler. Our cool British conditions should bring forth some of the world’s most enjoyable pinks in the next few years, and I would prefer English to Provence as my rosé thirst quencher any day.

This section almost divides into two parts. First, there are the red wines made from grape varieties specifically bred in laboratories to be able to develop both sugar and colour in cool to positively cold environments – Rondo, Regent and Dornfelder are the most common of these – and there are quite a few tasty reds being made, sometimes with a little oak aging adding to the texture and flavour.

And second, red wines made from the great French Burgundy grape, Pinot Noir, sometimes abetted by the slightly easier to ripen Pinot Noir Précoce (early) and Pinot Meunier. Wine enthusiasts call great Burgundy the ‘Holy Grail’ – often sought but rarely if ever found – even in Burgundy itself. Pinot Noir doesn’t like much heat, but it usually wants a bit more than is available in England, and most vineyards are better off using their Pinot for sparkling wine or for pink still wine. And yet, each year a few more wineries manage to make a red Pinot which is genuinely enjoyable to drink. It usually immediately gets showered with some kind of Burgundian comparisons, but it shouldn’t. These fragile, delicate, rather sappy, occasionally floral wines with attractively bright fruit based on flavours like cranberry, redcurrant, red plum, strawberry or rosehip or pale cherry, are truly English (or, in a couple of cases, Welsh). One or two wineries such as Gusbourne, Brightwell, Bolney and Chapel Down regularly produce enjoyable Pinot reds. The 2018 vintage will see another clutch of good red wines and it won’t stop there. Essex and the south-east of England have numerous vineyard sites that only require slightly more favourable conditions to produce good light red wines. And red Pinot is something that virtually every winemaker in the world wants to have a go at.

Finally, we are beginning to see plantings of warmer climate grapes such as Merlot (at Bluebell in Sussex), Cabernet Franc (at White Castle in Wales) and Pinotage (at Mannings Heath in Sussex), so the red wine world here is expanding year by year.

The grape variety is the most important influence on how a wine tastes. All grape varieties (as with different types of fruit and vegetable) have different flavours, giving different-tasting wines. Conditions in southern England are now pretty similar to what they were in Champagne 20 years ago and so it is not surprising that the Champagne grapes of Chardonnay, Pinot Noir and Pinot Meunier can now regularly ripen well enough for sparkling wines and increasingly for still wines, too. And nearly all the new plantings are of these varieties. There are numerous early-ripening, usually Germanic, grape varieties still left in the vineyards, often making very attractive still wines and sparklers. Of these the white Bacchus and Seyval Blanc are the most important.

Ripening red grapes in the British climate is much more challenging, and erratic summer and autumn weather can still prevent proper ripening. Even so, with better varieties and techniques, results are improving rapidly. Pinot Noir and Pinot Meunier, used mainly for sparkling but also for still, in particular rosé wine, are the main red varieties but Regent, Rondo and Dornfelder are other varieties which can do well here, and are crucial for rosé and red wines in the more marginal areas.

Variety % |

Total hectarage |

Hectares planted |

|

29.7% |

1063 ha |

|

28.9% |

1034 ha |

|

11% |

394 ha |

|

6.9% |

247 ha |

|

4.2% |

150 ha |

|

2.4% |

70 ha |

|

2.3% |

66 ha |

|

2.1% |

61 ha |

Others |

12.5% |

494 ha |

Key  Red grape variety

Red grape variety  White grape variety

White grape variety

*includes Pinot Noir Précoce

Chardonnay was planted in the very first of the revival vineyards in England – at Hambledon in Hampshire and at Oxted in Surrey in the early 1950s. Chardonnay made the greatest dry white wines in the world then – from Burgundy in northern France – just as it makes an awful lot of the best ones now from all around the globe. So you would want to be ambitious and plant the best. But it was a pity about the English climate. Year after year they could barely get the grapes to soften on the vine, let alone ripen up to a nice sugary autumn juiciness. Growers generally decided that specially bred cool climate vine varieties from Germany were a better bet, at least offering you the chance of making a wine of sorts, even if it tasted nothing like white Burgundy.

But the dream of getting Chardonnay ripe never went away and in the 1980s a few growers in Kent and Sussex dipped their toes into the Chardonnay waters again. Pretty cautiously. By 1990 only 20 hectares (50 acres) had been planted out of a national total of 929 hectares (2295 acres) of vines. Compare that with 2019 when there were 1034 hectares (2555 acres) of Chardonnay in a total of 3579 hectares (8845 acres). Yet things were about to change out of all recognition. First, Nyetimber from Sussex made a Blanc de Blancs sparkler in 1992 from 100 per cent Chardonnay grapes which won the Trophy for Best English Wine in 1997. Then Ridgeview, also from Sussex, won the Best English Wine Award in 2000 for their Cuvée Merret Bloomsbury 1996, a Chardonnay–Pinot Noir blend from Sussex and Kent grapes. These two wines simply transformed the way we looked at English wine. These were world-class sparklers and they were as good as Champagne. And the white grape variety of Champagne is Chardonnay.

I would have expected more people to rush in and plant Chardonnay, but they didn’t. Did everyone think these outstanding wines were just flashes in the pan? They weren’t. Ensuing vintages won trophy after trophy, and they also started beating Champagnes in blind-tasting competitions. But it wasn’t until the 2003 vintage, which brought the hottest summer conditions on record to Europe and the UK, that the critical mass believing in our ability to make the world’s best sparkling wine began to form. And if the UK began to believe that we could be the next great site for sparkling wines as the climate warmed up to something like the temperatures usually associated with Champagne, just a couple of hours’ drive south-east from Calais, the Champagne growers began to worry that their long reign at the top of the sparkling tree might be in danger of drawing to a close. You need fresh acidity in your grapes to make lively, mouthwatering sparkling wine. Champagne growers in 2003 were complaining that their grapes were literally stewing on the vine. But take a short hop to the north across the English Channel and that weather tempered by English conditions looked like a foretaste of a golden future. At last plantings of Chardonnay began to boom, and by 2019 they accounted for nearly 30 per cent of vines.

But we hardly ever see the word Chardonnay on the front label. No, and you don’t in Champagne either. We see an increasing number of wines labelled Blanc de Blancs – white wine from white grapes – and with every vintage more of these are likely to be pure Chardonnay. Some of our best sparklers are now all Chardonnay, sometimes austere, lemony and proud, sometimes stuffed with a citrus richness like lemon meringue smeared with soured cream. Ridgeview, Harrow & Hope, Gusbourne and Nyetimber are all superb. Yet the bulk of Chardonnay grapes are used in the so-called ‘Classic’ sparkling wine blend with the black Pinot Noir and Pinot Meunier grapes where they definitely add a crispness, a focus, a lick of clean, clear citrus fruit to the wine.

And what about the fabled still white Chardonnay, the new Chablis, the new Meursault – is there any sign of that here? Well, yes, but the best Chardonnays don’t taste like Chablis or Meursault; they taste gloriously, differently English. And there aren’t many of them, yet. My first glimpse of this future was at the end of the 1980s when a Hampshire winery called Wellow produced a Chardonnay so pale it could have been water, so light and ethereal I hardly dared sip it – but the flicker of beautiful Chardonnay fruit was there, the first modern spark, barely substantial enough to be fanned into flame. The flame is now bright – not big, not furious, but bright, as vineyards like Chapel Down’s Kit’s Coty and Gusbourne in Kent, and Clayhill in Essex show just what can be done. Chardonnay’s day job is making great sparkling wine, but you can’t blame it for moonlighting now and then.

So Bacchus is Britain’s New Zealand’s Sauvignon Blanc is it? Well, well. I suppose it could be. A generation or two ago there wasn’t any New Zealand Sauvignon Blanc and New Zealand’s wine reputation was far worse than England’s is today. And Sauvignon Blanc wasn’t exactly much sought after, either. There were a few decent examples from Bordeaux and the Loire Valley in France (where they didn’t put the grape name on the label, so you probably didn’t know you were drinking Sauvignon), and a few from northern Italy, and from Austria (where they helpfully call it Muskat-Silvaner). So Sauvignon came from almost nowhere to being a global star hand in hand with New Zealand becoming a global star after languishing for its entire wine existence as a grubby-tasting joke.

So there could be some sort of parallel here. Not a total one, because New Zealand swept to prominence on the back of Sauvignon Blanc’s ability to make astonishing white wines the like of which the world had never seen, while its sparkling wine scene is still surprisingly unspectacular. England’s rampant rush to fame is on the back of a series of sparkling wines made from the same grapes as Champagne, in the same way as Champagne, and often from very similar soil and climate conditions, which have equalled and increasingly surpassed the quality of equivalent Champagnes. But the still table wines, of any colour, lag well behind.

Frankly, there is no dishonour in this – Champagne makes very few still wines you’d want to drink, and Burgundy, using the same grape varieties but grown further south, doesn’t make many exciting sparklers. Most famous regions specialise. Well, yes and no. Most famous European wine regions specialise, sometimes literally only producing a single type of wine from a single grape variety. But most New World wine countries are keen to try as many different wine styles as they think might work. Europe usually has rigid wine laws saying what you can and can’t do, often worked out over the centuries. The New World is ready to give everything a go. And with England at the very northern tip of being able to barely ripen grapes like Chardonnay and Pinot Noir, which always make the best fizz when they’re barely ripe, but not the best still wine, another grape variety is going to be needed to spearhead any kind of still wine revolution.

Because England is so cold in wine terms, not many top grape varieties will ripen here. Producers such as Rathfinny and Denbies have tried the cool climate classic Riesling without success. Chenin Blanc from the Loire Valley hasn’t worked, either. You would think that Sauvignon Blanc might work. Well, it may, since tasty examples are beginning to creep out from wineries such as Woodchester in the Cotswolds, Denbies and Greyfriars in Surrey, Polgoon in Cornwall and Sixteen Ridges in Herefordshire (the polytunnels help with these two). Even Albariño (the grape from Galicia in the cool north-west of Spain) has made an appearance at Chapel Down. No, it needed one of the specially bred German vine crosses to step up – preferably one without too long a name and too many umlauts. Bacchus fits the bill.

Bacchus was ‘created’ in Germany as long ago as 1933 and, like most of these vine crosses, is pretty much a sugar machine in Germany’s warmer conditions. But in Britain, Bacchus ripens much more slowly and holds on to its acidity and consequently its bright elderflower and hedgerow scent that would be lost in sunnier climes. The flavour can be a little sappy, the acid reminiscent of mild lemon zest, and the fruit might even be peachy or at very least as ripe as a good English eating apple or a crisp greengage plum. The wine can be dry, or not quite dry. One or two producers like Chapel Down have even tried aging it in oak barrels and to my surprise it works quite well. There is even some sparkling Bacchus. It took a while for Bacchus to get going here – I did two tastings of over 100 English white wines in 1991 and there were only three Bacchus wines included, and only the wine from Three Choirs was much fun. It’s a different story now. Obviously wine judges like Bacchus because its wines regularly win the top still white wine awards in wine competitions in the UK, although sunny vintages like 2018 will probably give Chardonnay a healthy kick up the charts. And Bacchus will grow just about anywhere. It’s excellent in Essex and Norfolk (New Hall, Flint and Winbirri), excellent in Kent and Sussex (Chapel Down and Bolney), and is happy right across the West Country down to Cornwall (Camel Valley). And the British wine-drinking public are catching on, too – just as they did with New Zealand Sauvignon Blanc. The flavour’s not that similar, but the wine is fresh and bright and fairly low in alcohol – and you couldn’t get a better name for a wine grape than Bacchus, the Roman god of revelry and wine, the god of fun.

Every dog has his day. Every grape variety will find somewhere in the world where it can flourish. Even vines that are banned, uprooted, exterminated and despised can still find some little corner, some little nook, where soil and climate just briefly intersect with a grower’s passion and talent. And a super wine can result. Seyval Blanc was created through cross-breeding in France in 1921. But it’s banned from all the French quality wine areas because it isn’t a pure Vitis vinifera species (the grape species from which nearly all the world’s quality wine is made), and they’re very strict about that in France.

Actually it does make pretty rubbish wine in France, but in England, it finds its niche. It ripens early, so can cope with the vagaries of the English climate. It’s got high acids, and doesn’t have a particularly appealing flavour by itself. There’s something slightly feral, slightly like picnic nuts that had fallen in the mud, but you ate them anyway, like eating green apple peel by itself without the flesh – and did you wash your hands? Owen Elias, once of Chapel Down, and one of England’s top winemakers, says Seyval Blanc tastes of raw potato and cabbage.

So you sort of wonder why anyone should plant it? Well, it absolutely divides opinion, but I’ve been tasting Seyval Blanc for over 30 years; I remember some spicy, vivid, very appetising Seyval from Breaky Bottom made in years like 1984. Spots Farm at Tenterden in Kent made green and smoky but honeyed dry Seyval in 1983. And these – especially the wine from Breaky Bottom – aged for years, and really did develop flavours more like dry French wines than those of any other variety. Which was probably the whole point. Nearly all the grape varieties in the early revival after the Second World War were German-inspired and made off-dry, rather scented whites at their best (some of the original winemakers tried to make them dry, but few outside the dental profession found much pleasure in them). Seyval could give a passingly decent impersonation of something like a Muscadet or a Petit Chablis. To be honest, in the hands of someone like George Bowden at Leventhorpe Vineyard in Yorkshire, it still does.

But Seyval in southern England is now there largely because it can produce good crops of fairly neutral, quite high acid juice that works well as the basis for sparkling wine or as part of a sparkling blend. None of the top sparkling blends include Seyval any more, yet producers like Camel Valley, Breaky Bottom, Bluebell, Denbies and Three Choirs still include it in some of their blends. You can still just about taste that rustic green apple and muddy nut quality, but I’m really quite fond of it. After all, it’s very English, and no one else does it quite like that.

Since these two white and off-white members of the Pinot family are reckoned to ripen quicker than Chardonnay you would expect a rush to plant them in England and Wales. Well, there hasn’t exactly been a rush, but they are slowly making their presence felt, and since they are both permitted varieties in Champagne, they do have a certain attraction for English bubbly producers.

Pinot Blanc is often rather disingenuously called ‘Chardonnay’ around the world since Chardonnay is an easier name to sell. The fact that Pinot Blanc ripens more quickly and gives bigger yields than Chardonnay makes the deception profitable. There is no need for deception here in the UK since we are at the beginning of the journey toward fine dry white still wines. And Pinot Blanc works well here. Chapel Down has made a really nice fresh Pinot Blanc since the turn of the century and Stopham in Sussex have specialised in it. Stopham also makes a full, spicy, slightly tropical Pinot Gris, as do Bolney (also in Sussex) and others. This is the same grape as the Italian Pinot Grigio – which is usually a fairly neutral wine. But Pinot Gris is the French name for the grape and in Alsace it can make succulent, honeyed wine. This is the path English producers will be following. Some producers like Rathfinny blend the two together.

During the 1980s the British drank more wine from the Müller-Thurgau grape than from any other variety. Why? Because most of the wine we drank then was pretty ordinary German stuff like Liebfraumilch or Piesporter Michelsberg – and Müller-Thurgau, easy to ripen, and likely to literally weigh itself down with vast crops of tasteless grapes, was the workhorse of such wines. But shove Müller-Thurgau in the damper, colder soils of Britain, where yields of grapes were nothing like so gross as in Germany, and where the grape only crept to ripeness even in warm years – and you could make very nice wine from this much abused grape. In the 1990s it was England’s most widely planted variety, as English producers tried to ape the Germans. At its best, from producers such as Pulham St Mary in Norfolk, Breaky Bottom in Sussex, Syndale Valley in Kent and Wootton in Somerset, Müller-Thurgau was lightly floral, with a pleasantly crisp leafy green acidity and usually a few grams of sugar left in it. Better than Liebfraumilch? Definitely. But there is now barely a vine left in England.

Although Chardonnay and Bacchus are the two grape varieties that get the most attention, and simply by themselves cover about 40 per cent of the British vineyards, there are various other grape varieties that were famous once. Seyval Blanc and Müller-Thurgau are two obvious examples, and there are a few varieties, carefully bred for the colder, damper conditions of many parts of Wales and the north of England, which deserve a mention.

In the 1980s and ’90s, you’d see an awful lot of wines labelled Müller-Thurgau. But there were various other Germanic vine crosses too, some of which were rather good. Huxelrebe doesn’t sound very appetising but can make very snappy, leafy, rather gooseberryish wines, especially in Kent (I always liked Biddenden’s Hux), and there’s still some planted. Siegerrebe is a very early ripener that can make rich, honeyed, almost tropical wines – Three Choirs in Gloucestershire are famous for it. Ortega has turned out to have a genuine role to play – it ripens fast and is very susceptible to noble rot, the fungus which concentrates the juice and gives enough sweetness to make dessert wines. Denbies regularly makes a cracker in Surrey. Varieties like Reichensteiner, a rather bland but early ripening variety, Schönburger, Würzer, Würzburger and Ehrenfelser are quietly fading away. Madeleine Angevine – Mad Ange as growers call it – is proving surprisingly resilient and makes very attractive wines in Suffolk (Giffords Hall), Hampshire (Danebury), Yorkshire (Leventhorpe) and elsewhere – mellow, soft, ever so slightly smoky. But there is a bunch of new varieties, very specifically bred for the cold – they’re popular in countries like Denmark and Sweden. The most important are Solaris, Orion and Phoenix. In Wales and the north of England, they are crucial and produce wines with real flavour and personality. If global warming continues its relentless march, they may eventually give way to the big beasts like Chardonnay, so enjoy them for what they are – the best varieties at the moment for some of our marginal areas.

You simply can’t stop winemakers planting Pinot Noir. All over the world, from the heat of the eastern Mediterranean, to Australia and Argentina, to California and the Pacific Northwest, as well as all over western Europe, wine growers crave success with Pinot Noir and so Pinot Noir is planted, rarely with memorable results, and usually in conditions that are too warm and too dry for it to flourish. Burgundy, its heartland in eastern France, isn’t warm and isn’t dry and Pinot Noir only ripens satisfactorily on a tiny sliver of one east-facing slope. Champagne, further north in France, is less warm and less dry, and despite rarely making still red wine from Pinot Noir that would turn many heads, the grapes do ripen enough to form the basis for superb sparkling wine, since sparklers are best made from grapes that are barely ripe.

And then there’s Britain. Above all, the south of England, stretching from Kent and Sussex to Hampshire and Dorset via Surrey and the Thames Valley. Here, it’s even cooler than in Champagne. Here, it’s often even wetter. But as the climate changes, particularly in the last 20 years, more and more vineyard sites are proving that they can manage the balancing act of slowly edging the Pinot Noir toward ripeness, usually in October, without ever letting its delicate, almost fragile cool climate flavours descend into the jammy ripeness which occurs so readily in warmer climes. Such grapes, with their long period sitting on the vine as the summer fades and the mellow warmth of autumn takes over, can build up fabulous flavours at low alcohol levels – perfect for sparkling wine.

And Pinot Noir is massively helped in the south-east and in Hampshire by soils – often chalky, sometimes sandy – that can be indistinguishable from the soils of Champagne, which is, after all, only a couple of hours’ drive from the Channel port of Calais. These British soils have shown that they can produce grapes as suitable for sparkling wine as the soils in Champagne. Yet the fascinating thing about Pinot Noir in England is that it also excels on heavy clay soils, like those of the Kentish Weald or the Essex coast. It doesn’t excel on clay in France. In France they will tell you that Pinot Noir is a very fussy grape and the marriage of soils, aspect to the sun, amount of heat, sunshine hours, the wind, the rain – all that – must just fit precisely together for this variety to produce interesting results. That’s a lot of variables, and even Burgundy and Champagne struggle to piece the jigsaw together.

Will Britain find it any easier? No. But has Britain got conditions as good as those in France for Pinot Noir? Well, for still red wine, maybe not. Yet since cooler parts of the world have at last been able to produce good to excellent red wine that really doesn’t taste like Burgundy at all, England might find some special places where an entirely English-tasting red wine is possible. And it won’t be from conditions or soils like those of Burgundy. Pinot Noir doesn’t like heat, but it rots easily and so likes to stay dry. Kent and Essex are two of the driest parts of England. Even on heavy clay soils, Pinot is beginning to make wines to turn a head or two from these counties. Not like Burgundy, but nice.

As the climate warms, we will certainly see more wineries making a stab at Pinot Noir red, but right now, its best role as a still wine is pink. Less ripe grapes with less colour and sugar can make delicious, refreshing pink wine. Particularly after the explosion in planting during 2017–19, there are going to be a lot of young Pinot Noir vines producing grapes that need to be quickly turned into wine and sold for cash flow reasons alone. Pinot Noir pink is perfect for this, and we should shortly be making some of Europe’s best dry rosé.

But Pinot’s main job is to provide the base wine for sparkling wines. Pinot Noir is a black grape, but the juice is colourless, and if you press the grapes very carefully you can avoid staining the juice. Two-thirds of the grapes in Champagne are black, and most of the fizz they produce is white. Champagne employs the most delicate, precise grape presses in the world, and these presses are now appearing all over England, demonstrating just how serious the winemakers are. There are now 1063 hectares (2626 acres) planted with Pinot Noir in England and Wales, out of a total of 3579 hectares (8845 acres). That makes Pinot Noir the most planted variety by a whisker from Chardonnay – each year, Pinot Noir is jostling with Chardonnay to boast the highest acreage. And despite being less predictable when it comes to things like setting a crop, grape growers are surprised at how adaptable it can be if you care for it in the vineyard. Clearly it revels in the chalk and sandstone and gravel soils, but its ability to give really tasty crops from clay, so long as the weather is dry, is something of a revelation.

The majority of the Pinot Noir wine is blended with Chardonnay to make what is called a ‘Classic Cuvée’– the fuller, broader textures and flavours of Pinot Noir (and sometimes, Pinot Meunier) complementing the leaner, more vivacious character of the Chardonnay. White Blanc de Noirs from Pinot Noir by itself is so far a less popular style but is bursting with flavour and personality and wineries like Exton Park, Ridgeview and Jenkyn Place make wonderful examples. Most of the pink sparklers are made by blending Pinot with Chardonnay, but there are some so-called Rosé de Noirs pinks that match the best from Champagne, from wineries like Coates & Seely, Hattingley Valley, Ridgeview and Exton Park.

Pinot Noir may be finicky, may be mercurial, may be unpredictable, but in Britain, for sparkling wines above all, it has found a home.