Victoria

Victoria was lucky. She was eighteen and didn’t have to help much around the house. She had a paying job! She did housework for Mrs. Harrington. Mrs. Harrington often gave Victoria leftovers to take home to us. Ham, roast beef, and even lamb! Mrs. Harrington used to give Victoria dresses she didn’t want to wear anymore. Once she even took Victoria to New York and bought her a pair of high heels with bows!

The Harringtons were rich. Mr. Harrington was the owner of the cotton mill. They had a son Curtis who was my age. He was in my class at school, but I didn’t have anything to do with him. Curtis

was fresh and always got into trouble. The older son, Andrew Harrington, was a “super,” or superintendent at the mill. He used to sneak home early to talk to Victoria before she left for the day. I think he was in love with her.

He took her roller-skating, and they went downtown to the movies every time a new one was playing. Andrew had a car and wore polished shoes and a necktie. Ma wanted Victoria to marry him. Ma said in America this could happen.

Victoria knew about everything. She fixed her hair in the latest style, and she knew all about the new dresses and hats. She knew every single word of the popular songs and sang right along when they were played on the radio.

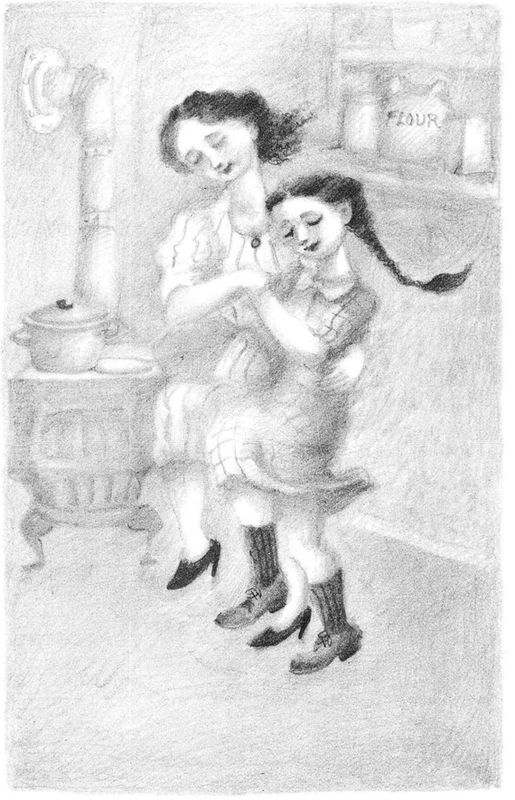

She was a great dancer, too. She liked to practice with me so she’d look good when she went out with Andrew. She’d turn on the radio music, and we’d dance all around the kitchen.

Walter never wanted to join us. “Not me. I don’t have dancing feet,” he’d say.

Dancing was such fun. We’d twirl and kick and swing! We’d get to giggling and shrieking. Walter

and Ma would get caught up in it. They’d laugh and shake their heads.

“Oh, you two!” Ma would say.

Pa didn’t approve of dancing and music.

“Crazy stuff! You won’t get ahead in life wasting your time like that!” Pa said.

Once Pa and Victoria had a big fight about her wearing lipstick, but Victoria wore it anyway. Pa let her get away with a lot because she had a paying job.

“If it weren’t for Victoria, we’d be on relief,” Pa said. That made Ma cry. The city gave out a little money to those who didn’t have work.

One time Walter said, “It’ll be better next year. I’ll be sixteen and quit school and get a job.”

“And what job will that be, wise guy?” Pa asked. “Who’ll hire a stupid like you? Aah!”

Walter left the house and slammed the door.

“He’s a good son,” Ma said. “He wants to help. Don’t talk to him like that.”

Why did Pa have to be so mean? I stood at the window and watched my brother shuffling down the street. He kicked rocks. He kicked a trash can.

I wanted to open the window and yell, “Walter, you’re a good son! You’re a good son!”

Victoria joined me at the window. “Pa sure is hard on him. Pa’s just like Walter—they both have a lot on their minds.”