Police

Walter was loading the stove with coal, and Pa was sitting in the rocking chair, trying to read the newspaper.

“Come here, Wanda. What’s this word?”

“That’s ‘economic,’” I said.

“And what’s this?”

“That says ‘government predictions.’”

“You’re smart, Wanda. You’re gonna be somebody,” Pa said. I smiled inside. I liked when Pa said things like that to me.

The knock at the door was loud and urgent. Ma and I were startled and almost spilled the bowls of cabbage soup we were carrying to the supper table.

“Who is it?” Pa called out.

“Police. We need to talk to you.”

Pa hurried to the door and unlocked it. “Yes, sir?” he asked.

“Are you Mr. Malinski?”

“Yes, sir,” Pa answered.

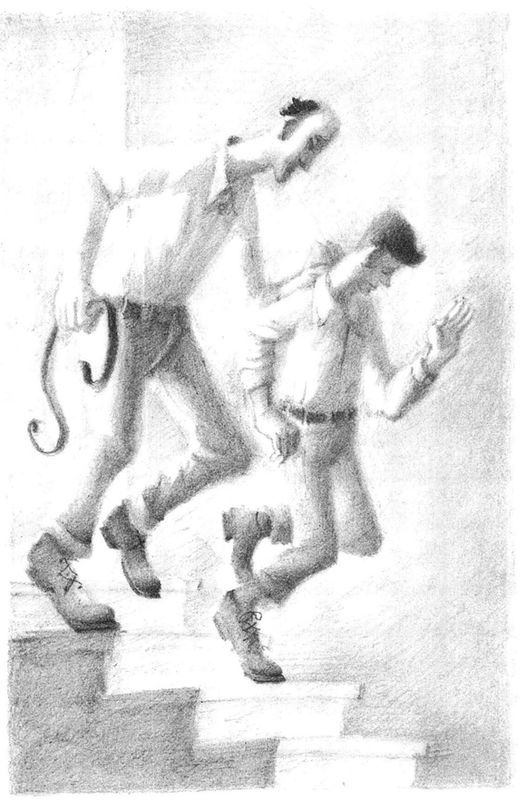

Pa stood aside as the two officers entered. It was crowded in our kitchen. A clothesline with our wet laundry was strung across the room, and it made the room even smaller. The policemen had to duck under the laundry as they came in. The tall one turned to his partner and smirked.

“Mr. Malinski, do you have a son named Walter?” the other officer asked.

“Yes, sir. I do,” Pa answered. “Why? What is it?”

Walter moved to Pa’s side.

“Are you Walter?” the officer said.

“Yes, sir.” Walter looked scared. We were all scared.

“Mr. Malinski,” the policeman said. “There was an incident down by the railroad tracks this afternoon. Curtis Harrington says your son Walter attacked him with a knife.”

“My son has no knife!” Pa said.

“What? What?” Ma asked, grabbing my arm.

“My son has no knife!” Pa insisted.

Walter reddened.

“Do you have a knife?” the policeman asked.

“Yes, sir. I do,” my brother answered.

“Go get it, then,” the policeman said.

Walter went to his cot and took the penknife out from under his mattress. Pa’s eyes flashed. I could hear his short, hard breath.

“Where did you get that? Where?” Pa demanded.

Ma was yammering in Polish, and I had to shush her.

Walter handed the penknife to the policeman.

“You’re very lucky, Mr. Malinski. Curtis Harrington’s father is a very important man in this town, and he has agreed not to press charges if we confiscate the knife.”

Then the officer spoke again to Walter. “You’d better wise up, kid. There are laws in this country. You can’t go around attacking people with knives.”

I saw the look on Walter’s face. I saw the look on

Pa’s face. I couldn’t restrain myself any longer. I grabbed Pa’s arm.

“Pa, Walter didn’t attack anyone. I was there. I know!”

Pa shoved me away. “Shut up, Wanda! Shut up!” he yelled. He shoved me away.

“Mr. Malinski, you’d better teach your children right from wrong,” the policeman went on. “This is America. You’re in America now.”

“Yes, sir. Yes, sir,” Pa answered.

The two policemen turned to leave and ducked back under the laundry. I heard the tall one say, “How can they live like this? It smells like something died in here!” I hated cabbage soup from that day on.

As the policemen left our house, the crowd of curious neighbors parted to let them pass. Pa went to the window and pulled down the shade.

Then he turned to Walter. “You! You! You bring police to this family! You bring shame to this family!” And he took his belt off and hit Walter over and over again.

“Pa, don’t! Pa!” I pleaded.

“Stop! Stop!” Ma cried.

Pa opened the cellar door and pushed Walter down into the dark. “A rat! That’s what you are! Sleep with the rats!” Pa slammed the door.

“Let’s eat!” he said to Ma and me.

We sat down with our bread and our soup. I didn’t want to eat. I never wanted to eat again. I put my head in my hands and sobbed.

“Eat!” Pa said, pounding the table.

I pushed my chair back and ran to my room. I threw myself on the bed and wept.

Some time later Ma came into my room with a hunk of bread. “Here. For you and Walter. Go give it to him.”

I went into the kitchen and glanced at Pa sitting with the newspaper. He said nothing.

When I opened the cellar door, Ma said, “Tell Walter to come up. My son does not sleep with rats!” She glared at Pa. He said nothing.

When Victoria came home from the Harringtons’, she took Walter outside for a talk. It was late when

they returned, and I saw her hug Walter. She came into our room and put on her nightgown and got under the covers. She was crying.

“What’s the matter?” I asked.

“I don’t know if I ever want to be related to Curtis Harrington,” she said.

A couple of weeks later, there was a lot of excitement at school. Everyone was talking about it. It was in the newspaper, too. Podorozny’s Market had been robbed!

Mr. Podorozny and his family were asleep in their tenement above the market when they heard the loud crash of glass breaking. Mr. Podorozny ran downstairs in his long johns and confronted a boy stealing money from the cash register. It was the rich boy, Curtis Harrington, stealing! Curtis tried to run away, but Mr. Podorozny stopped him with a broom and held him until the police arrived. The police put Curtis in the paddy wagon and took him to the station. Mr. Harrington had to come down to get him. He offered Mr. Podorozny a lot of money to settle up, but Mr. Podorozny wanted to press

charges. He said Curtis was a rotten kid who needed to learn a lesson. Victoria heard Mr. and Mrs. Harrington talking about sending Curtis away to boarding school.

Ma said Curtis was turning out bad probably because his father hollered at him too much. Pa said maybe Curtis was turning out bad because his mother was too softhearted. But Victoria said, from what she saw, no one paid any attention to Curtis at all.