In my coaching I have only a handful of “magic moves.”

Apologizing is a magic move. Only the hardest of hearts will fail to forgive a person who admits they were wrong. Apology is where behavioral change begins.

Asking for help is a magic move. Few people will refuse your sincere plea for help. Asking for help sustains the change process, keeps it moving forward.

Optimism—not only feeling it inside but showing it on the outside—is a magic move. People are automatically drawn to the confident individual who believes everything will work out. They want to be led by this person. They’ll work overtime to help this person succeed. Optimism almost makes the change process a self-fulfilling prophecy.

What makes these gestures magical is how effectively they trigger decent behavior in other people and how easy they are to do.

This chapter introduces a fourth magic move: asking active questions. Like apologizing or asking for help, it’s easy to do. But it’s a different kind of triggering mechanism. Its objective is to alter our behavior, not the behavior of others. But that doesn’t make it less magical. The act of self-questioning—so simple, so misunderstood, so infrequently pursued—changes everything.

I learned about active questions from my daughter, Kelly Goldsmith, who has a Ph.D. from Yale in behavioral marketing and teaches at Northwestern’s Kellogg School of Management.

Kelly and I were discussing one of the eternal mysteries in my field—namely, the poor return from American company’s $10 billion investment in training programs to boost employee engagement.

Part of the problem, my daughter patiently explained, is that despite the massive spending on training, companies may end up doing things that stifle rather than promote engagement. It starts with how companies ask questions about employee engagement. The standard practice in almost all organizational surveys on the subject is to rely on what Kelly calls passive questions—questions that describe a static condition. “Do you have clear goals?” is an example of a passive question. It’s passive because it can cause people to think of what is being done to them rather than what they are doing for themselves.

When people are asked passive questions they almost invariably provide “environmental” answers. Thus, if an employee answers “no” when asked, “Do you have clear goals?” the reasons are attributed to external factors such as “My manager can’t make up his mind” or “The company changes strategy every month.” The employee seldom looks within to take responsibility and say, “It’s my fault.” Blame is assigned elsewhere. The passive construction of “Do you have clear goals?” begets a passive explanation (“My manager doesn’t set clear goals”).

The result, argued Kelly, is that when companies take the natural next step and ask for positive suggestions about making changes, the employees’ answers once again focus exclusively on the environment, not the individual. “Managers need to be trained in goal setting” or “Our executives need to be more effective in communicating our vision” are typical responses. The company is essentially asking, “What are we doing wrong?”—and the employees are more than willing to oblige with a laundry list of the company’s mistakes.

There is nothing inherently evil or bad about passive questions. They can be a very useful tool for helping companies know what they can do to improve. On the other hand, they can produce a very negative unintended consequence. When asked exclusively, passive questions can be the natural enemy of taking personal responsibility and demonstrating accountability. They can give people the unearned permission to pass the buck to anyone and anything but themselves.

Active questions are the alternative to passive questions. There’s a difference between “Do you have clear goals?” and “Did you do your best to set clear goals for yourself?” The former is trying to determine the employee’s state of mind; the latter challenges the employee to describe or defend a course of action. Kelly was pointing out that passive questions were almost always being asked while active questions were being ignored.

My Brief History with Engagement

To the untrained eye this was a geeky discussion about semantics between a father and daughter who are overinvested in the intricacies of organizational behavior.

But this was a watershed moment for me. We were talking about employee engagement, a cherished and loaded concept among human resources professionals, who happen to be one of my major client constituencies.

In management circles, engagement is one of those mystically idealized conditions for employees, the equivalent of an athlete being “in the zone” or an artist being in a state of creative “flow.” To human resources professionals, employee engagement is not quite the naïve vision of “Whistle While You Work” in Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs—but it’s close.

Like “full employment” or world peace, however, employee engagement is also elusive and misunderstood. I have spent years thinking about it and discussing it with professionals. Yet I too have had a checkered history with the concept. Why is engagement so hard to instill in some people, so easy in others?

My puzzlement came to a head when I was invited to speak about coaching at a meeting of human resources executives. The presenters before me, chief HR officers from three leading corporations, were demonstrating why employee engagement is a major variable in the success of an organization. The next described the key drivers of engagement, which included laudable ambitions such as:

• Delivering fair pay and benefits.

• Providing the right tools and resources.

• Creating a learning environment that encouraged open communication.

• Providing variety and challenge in work assignments.

• Developing leaders who delegated well, nurtured their direct reports, provided recognition and timely feedback, and built interpersonal relationships.

It all made sense. Who could argue that committed employees willing to go the “extra mile” for their companies wouldn’t be more productive than disengaged employees who don’t care? Who would take the position that underpaying people and denying them the right tools to do their job was a great way to increase engagement?

Then the HR chiefs noted that engagement was near an all-time low! (Gallup research in 2011 showed almost no improvement—with 71 percent of Americans saying that they are “disengaged” or “actively disengaged” in their work.*) They didn’t have an explanation for this disconnect and the poor return on investment.

This was news to me at the time. It didn’t add up that after all the corporate investment in training, engagement wasn’t improving.

But it shouldn’t have been a shock. I saw supporting evidence nearly every time I took my seat on a plane. On a typical three-hour flight, some flight attendants are positive, motivated, upbeat, and enthusiastic. They are models of employee engagement. Other attendants are negative, demotivated, downbeat, and miserable. They are “actively disengaged.”

Why the difference? The environment for both attendants is identical—same plane, same customers, same pay, same hours, even the same training—and yet they are demonstrating massively divergent levels of engagement.

I started conducting my own private engagement tests at airline counters and club lounges. Whenever I was asked to show my American Airlines frequent flyer card, which at 11 million miles makes me one of the airline’s more loyal customers, I noted the employee’s response. It’s not a distinctive card (not like the sleek black matte card George Clooney receives when he reaches 10 million miles in Up in the Air), so I make sure it gets noticed by asking airline employees, “Have you ever seen one of these before?” In theory a fully engaged airline employee would see my impressive mileage and treat me like royalty—if only because I have showered the company with my patronage and cash. But given the engagement gap I’d experienced among the airline’s in-flight employees, I didn’t have very high expectations for the people on the ground.

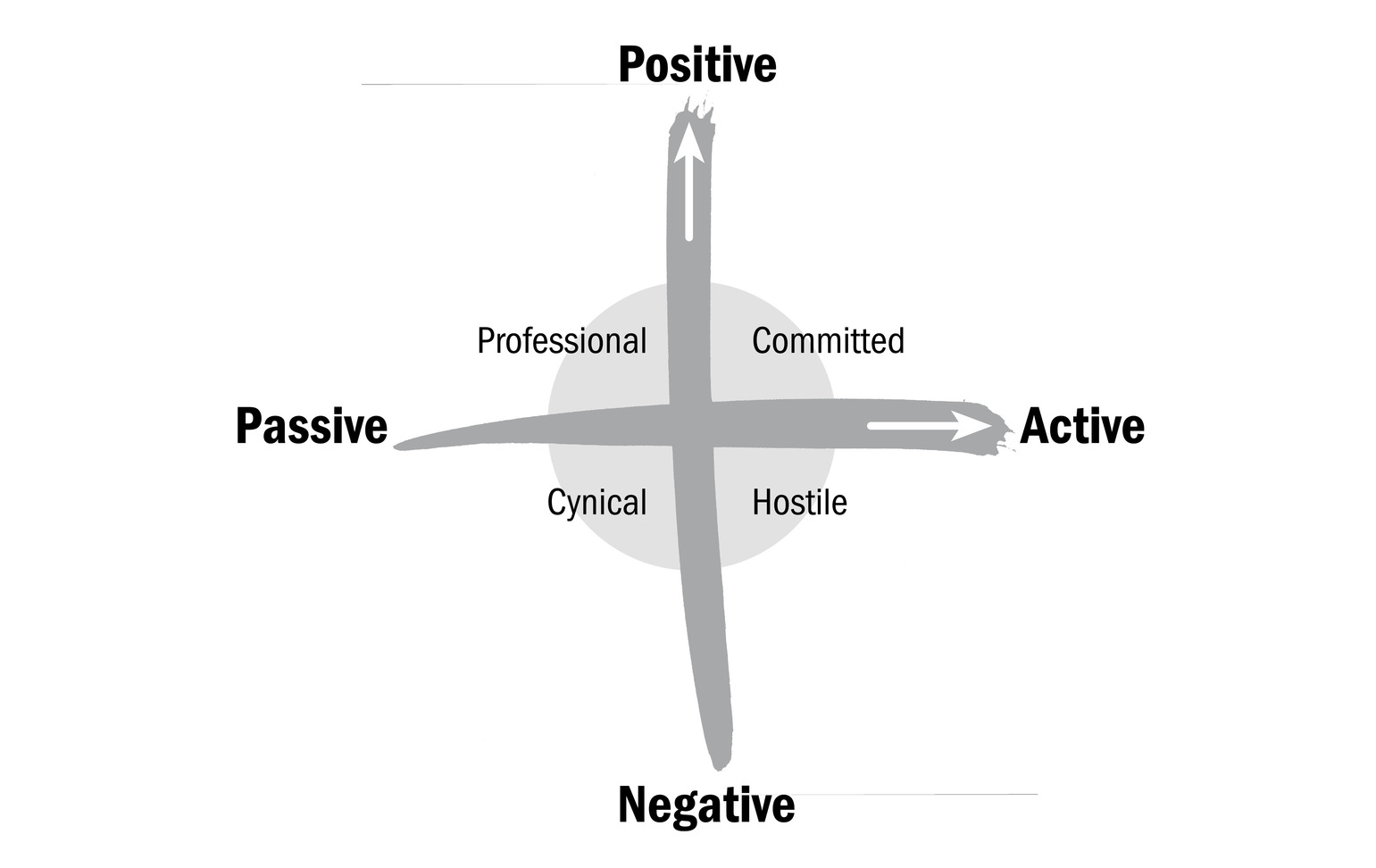

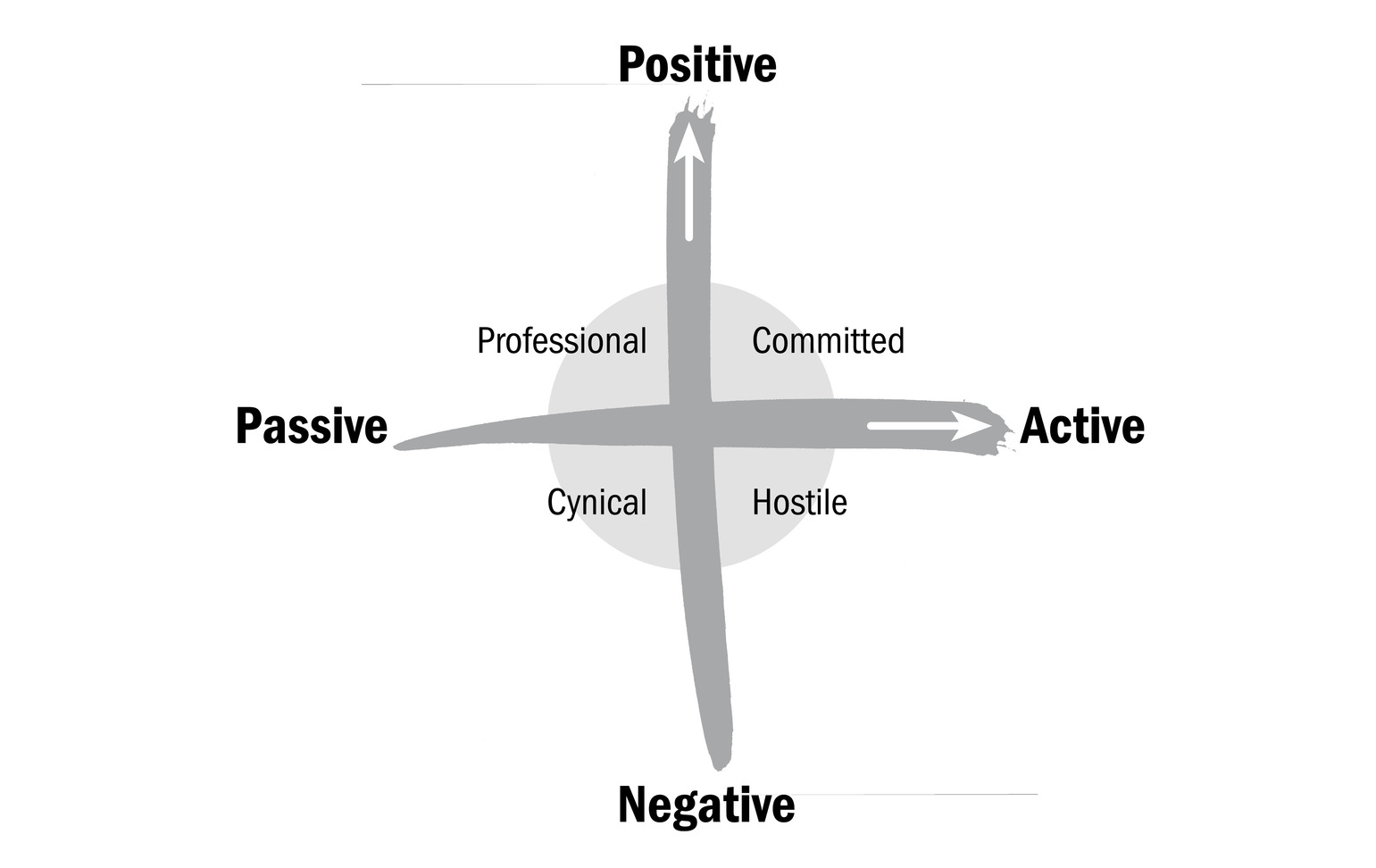

In my experience, fully engaged employees are positive and proactive about their relationship to the job. They not only feel good about what they’re doing; they don’t mind showing off their enthusiasm to the world. Using those qualities—positive versus negative, proactive versus passive—I tracked the responses to my 11 million miles card to distinguish four levels of engagement:

Committed: The proactively positive employees would examine the card as if they’d never seen it before, and say some variation on “Hey, this is cool.” Some would call over another employee to check out the card. They’d all thank me for my loyalty—and they meant it. Even though we were in the middle of a quickly forgotten exchange—it didn’t rise to the level of a transaction, certainly not a relationship—and would not see each other again, the employees made me feel great. That’s engagement.

Professional: Then there are the passively positive responses, best expressed by the woman behind the desk in Dallas who offered the sincere pleasantry, “We appreciate your loyalty, sir.” That’s okay. She made me feel appreciated. She was being a professional.

Cynical: The most common response I get is the passively negative tone of “That’s nice, sir.” Or “That’s interesting.” Bored with their job and indifferent to customers, these employees opt for the passive-aggressiveness of being superficially engaged with what they’re doing but conveying through their tone of voice that they really don’t care.

Hostile: At the bottom of the engagement barrel are the proactively negative types who dislike their jobs and can barely tolerate me. At their best, they treat me as an object of sympathy (“I hope that you don’t have to keep doing this much longer”). At their worst they attack me for simply existing, as in the man who took my card and said, “I’m really tired of you people who fly all the time and expect to get so much back from the airline because you have miles.” (The way he stretched out “miles” into three syllables was particularly gratifying. As a general rule, when I hear the words “you people” I know nothing nice will follow. And he didn’t disappoint.)

Whenever I meet “hostile” or “cynical” people in a service sector job, two questions come to mind:

• What genius hired you for a customer-facing position?

• What happened to you?

Answering the first question is at the core of my professional life. After that meeting, I significantly increased my exhortations to companies on the importance of follow-up after they train their employees. It’s one of my signature themes: People don’t get better without follow-up. So let’s get better at following up with our people.

Putting Active Questions to the Test

My daughter made me realize that I was still too focused on the company. The fact that I was wondering who hired these people and who put them in the front lines of customer service was a good indicator that I was still holding the employer, not the employee, solely responsible for creating engaged workers. By stressing better follow-up, I was merely increasing the company’s burden, asking them to be more thorough in documenting their employees’ failures.

There was nothing wrong with my message, but I was ignoring half of the equation: the employee’s responsibility for his or her behavior. The difference was not what the company was doing to engage the flight attendants. The difference was what the flight attendants were doing to engage themselves!

This was such a breakthrough for me that I initiated a controlled study with Kelly to test the effectiveness of active questions with employees who undergo training. The theory was that different phrasing of the follow-up questions would have a measurable effect because active questions focus respondents on what they can do to make a positive difference in the world rather than what the world can do to make a positive difference for them. (John F. Kennedy must have known this when he crafted one of the more memorable calls to action in American history: “Ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country.”)

In the first study, we used three different groups. The first group was a control group that received no training and was asked “before and after” questions on happiness, meaning, building positive relationships, and engagement.

The second group went to a two-hour training session about “engaging yourself” at work and home. This training was followed up every day (for ten working days) with passive questions:

1. How happy were you today?

2. How meaningful was your day?

3. How positive were your relationships with people?

4. How engaged were you?

The third group went to the same two-hour training session. Their training was followed up every day (for ten working days) with active questions:

1. Did you do your best to be happy?

2. Did you do your best to find meaning?

3. Did you do your best to build positive relationships with people?

4. Did you do your best to be fully engaged?

At the end of two weeks, the participants in each of the three groups were asked to rate themselves on increased happiness, meaning, positive relationships, and engagement.

The results were amazingly consistent. The control group showed little change (as control groups are wont to do). The passive questions group reported positive improvement in all four areas. The active questions group doubled that improvement on every item! Active questions were twice as effective at delivering training’s desired benefits to employees. While any follow-up was shown to be superior to no follow-up, a simple tweak in the language of follow-up—focusing on what the individual can control—makes a significant difference.