What is the most memorable behavioral change you’ve made in your adult life?

I’ve posed this question to hundreds of people—and rarely does the answer come trippingly to their tongues.

The quickest responses come from people who’ve eliminated a bad habit. When I posed the question to Amy, a fifty-one-year-old senior executive at a media company, she immediately took credit for quitting smoking.

“That’s not quite what I’m looking for,” I said. “Kicking cigarettes is admirable and hard. But smoking is also unhealthy and socially disdained. There’s a lot of external pressure to quit. I’m looking for voluntary behavioral change that made other people’s lives better because you were better.”

Amy thought about it. “Does being nicer to my mother count?”

That was more like it. Amy described a close mother-daughter relationship, perhaps too close. Her mother was in her late seventies and they spoke daily, but the conversation was governed by sniping and petty arguments. Parent and child were each engaged in a zero-sum game of proving herself right and the other wrong. “Love by a thousand cuts,” Amy called it. One day, triggered by her mother’s mortality and the realization that neither of them was getting younger, Amy decided on a truce. She didn’t tell her mother about it. She simply refused to engage in the verbal skirmishing. When her mother made a judgmental remark Amy let it hang in the air like a noxious cloud, waiting for it to vaporize from neglect. With her daughter unwilling to counterpunch, Mom soon stopped punching. And vice versa.

“What you did is not minor,” I said, congratulating Amy on an accomplishment more notable than quitting smoking. I asked her to imagine all the family holidays and Thanksgiving dinners and birthday parties and road trips that would be less fractious if people did as she did—declared a truce with their loved ones. “You changed the script for two people, not just yourself. That’s something to be proud of.”

Some people misunderstand the question. They recall a major career decision or an epiphany and confuse it with behavioral change. A financial executive cited his first year in law school when he knew that, unlike his father and brothers, he didn’t want to be a lawyer. That was a moment of clarity that triggered everything that followed—quitting law school, becoming a financial analyst—but it was a fork in the road, not a behavioral change. Likewise, the art dealer who, with a straight face, described the moment he “realized that not everyone comes at a problem with my point of view.” That’s an insight (and not all that unique) but unless it profoundly changed how he treated other people, that’s all it would have been—an insight.

A healthy number of people tell me about their triumphs of physical discipline and mental rigor: running a marathon, bench-pressing three hundred pounds, going back to school for an advanced degree, mastering bread making, learning to meditate. Again, commendable examples of self-improvement and not easily dismissed, but unless bread making or meditating has noticeably improved your behavior around others (as opposed to calming you down like taking a Valium), it’s not the interpersonal achievement I’m hoping to hear. You’ve adopted a worthwhile activity, not changed your behavior.

The majority of people are stumped. They can’t remember changing anything. (Quick question: what’s the most memorable behavioral change you have made?)

Their blank stares don’t surprise me. I get the same from most of my one-on-one clients in our first meeting. No matter how self-aware or alert to their surroundings these successful people may be, the need for behavioral change is not on their radar until I confront them with the evidence. We can’t change until we know what to change.

We commit a lot of unforced errors in figuring out what to change.

We waste time on issues we don’t feel that strongly about. We think, “It would be nice if I called my mother.” But if it really mattered to us, we would do it, instead of mulling it over, making the occasional call, but never committing in a way that’s satisfying and meaningful. We wish instead of do.

We limit ourselves with rigid binary thinking. Nadeem, for example, thought he had only two behavioral options in dealing with Simon: either grin and bear it (which was humiliating) or fight back (which only proved the folk wisdom, “Never wrestle with a pig—because you both get dirty but the pig loves it”). Nadeem didn’t appreciate that his environment—any environment—is supple. It offers more than either/or. He had to be shown that his awkward situation was an opportunity to model positive behavior that would burnish his image as a team player and, as an unexpected bonus, help Simon become a better team player.

Mostly, we suffer a failure of imagination. Until a few years ago, I had never coached an executive who was also a medical doctor. I’ve now had the privilege of coaching three: Dr. Jim Yong Kim, the president of the World Bank; Dr. John Noseworthy, the president of the Mayo Clinic; and Dr. Raj Shah, the administrator of the United States Agency for International Development. Along with being brilliant, they are three of the most dedicated, high-integrity people I have ever met.

Early in my coaching process with each doctor I went over the six Engaging Questions:

1. Did I do my best to set clear goals?

2. Did I do my best to make progress toward my goals?

3. Did I do my best to find meaning?

4. Did I do my best to be happy?

5. Did I do my best to build positive relationships?

6. Did I do my best to be fully engaged?

These were smart, heavily credentialed men who are not generally thrown by simple questions. But I could see a confused look and then silence as each man considered the fourth question: Did I do my best to be happy?

“Do you have a problem with being happy?” I asked.

In three separate interactions, each man responded with almost the same words: “It never occurred to me to try to be happy.”

All three had the intellectual bandwidth to graduate from medical school and ascend to chief executive roles, and yet they had to be reminded to be happy. That’s how difficult it is to know what we want to change. Even the sharpshooters among us can miss a really big target.

I can’t tell you what to change. It’s a personal choice. I could run through a list of gaudy qualities such as compassion, loyalty, courage, respect, integrity, patience, generosity, humility, etc. They are the timeless virtues that our parents, teachers, and coaches try to inculcate in us when we’re young and malleable. We’re frequently reminded of them in sermons, eulogies, and commencement addresses.

Being lectured on such virtues doesn’t compel us to be virtuous. A speech, no matter how pointed or eloquently delivered, rarely triggers lasting change—not if we lack a compelling reason to change. We listen, nod our heads in agreement, then go back to our old ways. A big part of it is that we lack the structure to execute our ambitions; we are visionary Planners but blurry-eyed Doers. But as with the three doctors, it’s also possible that some types of change never enter our minds.

That’s a big reason I introduce clients to the Engaging Questions early on. I’m forcing people to consider questions so basic we often forget to ask them. I couple these six questions with my trademark tutorial about the environment—how we don’t appreciate the good and (mostly) bad ways it shapes our behavior. And then I sit back and wait for the clients’ cranial wheels to start turning. In my experience, forcing people to think about their environment in the context of fundamental desires like happiness, purpose, and engagement concentrates the mind, makes people reflect on how they’re measuring up in those areas—and why.

When we assess our performance against the Engaging Questions and come up wanting in any way, we can lay the blame on either the environment or ourselves.

We love to scapegoat our environment. We don’t set clear goals because we answer to too many people. We falter on existing goals because we have too much on our plate. We’re unhappy because our job is a dead end. We don’t form positive relationships because other people won’t meet us halfway. We’re disengaged at work because the company refuses to help us. And so on.

As skilled as we are at scapegoating our environment, we are equally masterful at granting ourselves absolution for any shortcomings. We rarely blame ourselves for mistakes or bad choices when the environment is such a convenient fall guy. How often have you heard a colleague accept responsibility for whatever misery he’s feeling at work by admitting, “I’m a naturally miserable fellow”? The fault is out there somewhere, never within us.

Honestly assessing the interplay in our lives between these two forces—the environment and ourselves—is how we become the person we want to be.

My main goal in writing this book has been relatively modest: to help you achieve lasting positive change in the behavior that is most important to you. It’s not my job to tell you what to change. With time to reflect, most of us know what we should be doing. My job is to help you do it. The change doesn’t have to be enormous, the kind where people don’t recognize you anymore. Any positive change is better than none at all. If as a result of some insight gained here, you’re a little happier as you go through your day, or you have a slightly better relationship with the people you love, or you reach one of your goals, that’s enough for me.

But I’ve also tried to highlight the value of two other objectives. They don’t quite fit into the mold of the classic traditional virtues that our parents taught us. They’re more like positive states of being.

The first objective is awareness—being awake to what’s going on around us. Few of us go through our day being more than fractionally aware. We turn off our brains when we travel or commute to work. Our minds wander in meetings. Even among the people we love, we distract ourselves in front of a TV or computer screen. Who knows what we’re missing when we’re not paying attention?

The second is engagement. We’re not only awake in our environment, we’re actively participating in it—and the people who matter to us recognize our engagement. In most contexts, engagement is the most admirable state of being. It’s both noble and pleasant, something we can be proud of and enjoy. Is there higher praise coming from a partner or child than to hear them tell us, “You are always there for me”? Or anything more painful than to be told, “You were never there for me”? That’s how much engagement matters to us. It is the finest end product of adult behavioral change.

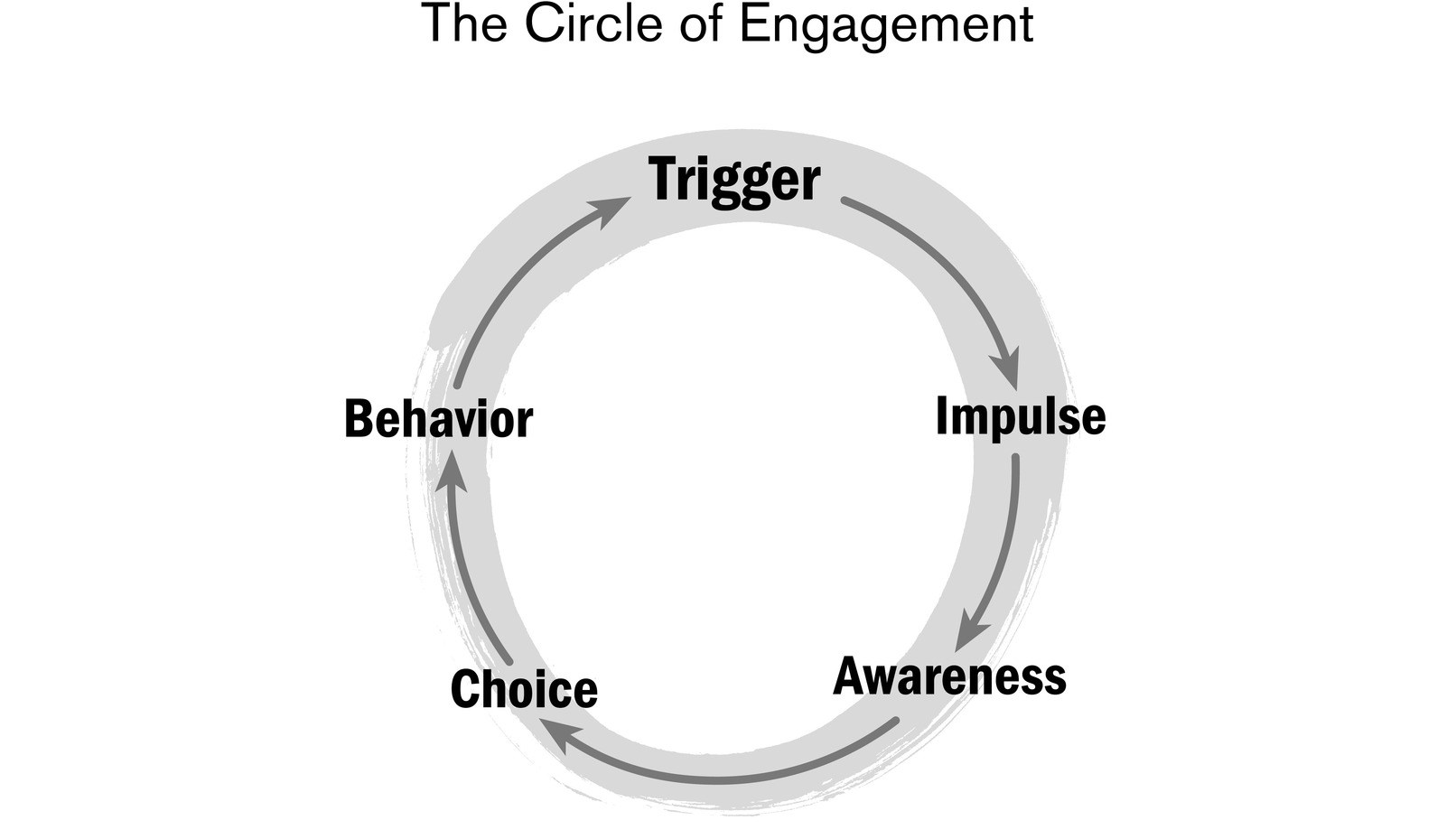

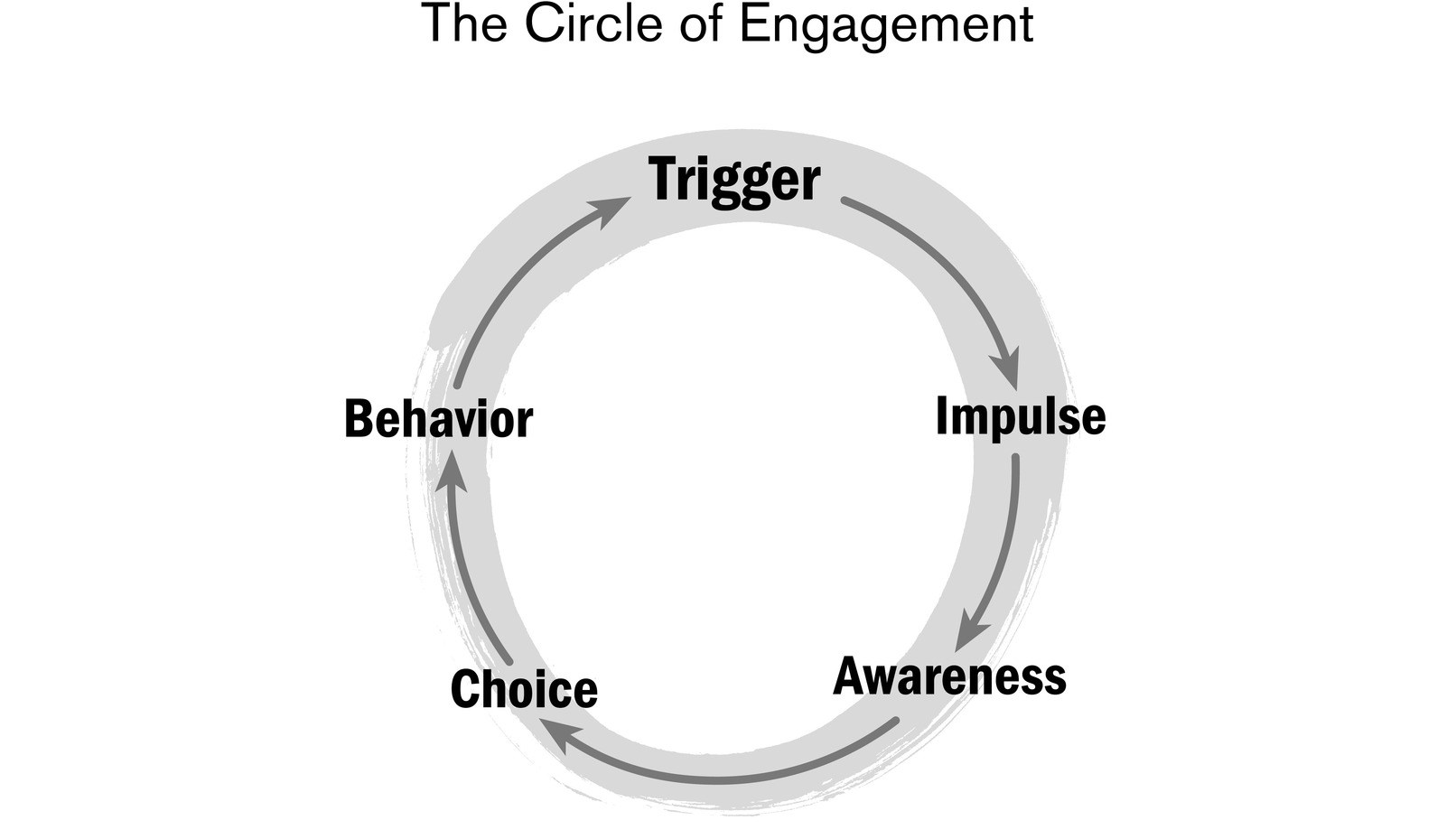

When we embrace a desire for awareness and engagement, we are in the best position to appreciate all the triggers the environment throws at us. We might not know what to expect—the triggering power of our environment is a constant surprise—but we know what others expect of us. And we know what we expect of ourselves. The results can be astonishing. We no longer have to treat our environment as if it’s a train rushing toward us while we stand helplessly on the track waiting for impact. The interplay between us and our environment becomes reciprocal, a give-and-take arrangement where we are creating it as much as it creates us. We achieve an equilibrium I like to describe as the Circle of Engagement:

This is an easily achieved state of equilibrium. Let me give you an example of how it works using an everyday event so common (but not trivial) we barely take notice (but should). The story came to me in an email from an executive named Jim who had been in one of my Graduate Executive classes at Dartmouth’s Tuck School of Business.

Jim’s wife, Barbara, called him at work when he was having one of those Category 4 hurricane kind of days. Everything going wrong: clients ticked-off, division chief riding him, assistant called in sick. His wife said, “I just need someone to talk to.” Evidently she was having a rough day at her job, too.

The statement I just need someone to talk to is a trigger—a trigger for Jim to stop what he’s doing and listen. He’s not being asked for his opinion or help. He’s not being asked to say anything at all. Just listen. It is the easiest “ask” of his day. He should cherish it as an unexpected gift.

But at the precise moment Jim hears Barbara’s voice, it’s not a certainty that he will accept the call as a blessing. A trigger, after all, leads directly to an impulse to behave in a specific way, and Jim had a full menu of impulses to choose from, not all of them desirable.

He could become even more frazzled than he was before the phone rang. In other words, use the trigger to elevate his existing emotions.

He could tell his wife that he’s really swamped at the moment and promise to call her back later or discuss it at home. In other words, delay the triggering moment for a time that’s more convenient for him.

He could give Barbara his perfunctory attention and multitask while she’s talking. In other words, award the trigger a lower priority than his wife attaches to it—and hope she doesn’t notice.

He could have self-righteous thoughts about how his wife’s problems pale in both severity and significance to his own and then demonstrate in exquisite detail that she is not as miserable as he is. In other words, he could compete with Barbara’s trigger and “win.” He could pursue the highly dubious strategy of proving that, once again, he is right and she is wrong.

Or he could listen.

These are all natural impulses. Who among us hasn’t felt grumpy or lapsed into a full-blown tantrum while being forced to listen to someone else complain? Or tuned out a friend’s whining by mentally traveling to another place? Or used another person’s complaining as an occasion to broadcast and glorify our own travails?

When we lack awareness (in many cases because we are lost in what we’re doing or feeling), we are easily triggered. The gap from trigger to impulse to behavior is instantaneous. That’s the sequence. A trigger leads to an impulse, which leads directly to a behavior, which creates another trigger—and so on. Sometimes it works out for us; we’re lucky and made the right “choice” without actually choosing. But it’s an unnecessary risk that can produce chaos. Awareness is a difference maker. It stretches that triggering sequence, providing us with a little breathing space—not much, just enough—to consider our options and make a better behavioral choice.

Jim wrote the email to let me know he made the right choice. Here’s his description of his first impulse at the triggering moment:

I was getting ready to point out that she wasn’t the only person having problems. Then I remembered your words in class: “Am I willing at this time to make the investment required to make a positive contribution on this topic?” I took a breath and decided to be the guy who she needed to talk to. I didn’t say a thing. When she finished venting, she said, “That felt good.” All I could say was, “I love you.”

This is the reciprocal miracle that appears when we are aware and engaged. We recognize a trigger for what it really is and respond wisely and appropriately. Our behavior creates a trigger that itself generates more appropriate behavior from the other person. And so on. This is what Jim accomplished with his wife’s trigger. She triggered something thoughtful and wonderful in him, and he reciprocated by triggering a feel-good response in her. In the most positive way, each had become the other’s trigger. Whether they knew it or not, they were running laps in a virtuous circle of engagement—and keeping the circle unbroken.