5

Climato-Economic Pressures on Cultural Identity

Evert Van de Vliert

Extreme temperatures are effective killers. All living species on our planet can easily be frozen or burned to death. No plant, no animal, no human is impervious to the problems posed by bitter winters and scorching summers. This double danger is particularly harmful to humans, who feed on plants and animals. Both men and women have to navigate between the Scylla of climatic cold and the Charybdis of climatic heat, with a number of consequences. First, they have evolved (a) basic needs for thermal comfort, nutrition, and health; (b) worries about cold winters and hot summers; and (c) strategies to exploit the seasonal availability of plants and animals. Second, few ancestors have migrated to arctic or desert regions where livability is highly problematic. Third, our ancestors have created trillions of ideas, practices, and artifacts, including money, to survive and thrive in cold and hot places. Fourth, all newborns nowadays enter into a given climato-economic environment to which they react. As a fifth consequence, highlighted here, some features of personal identity vary typically among inhabitants of differentially cold and hot habitats.

This chapter explores the relationship between the ambient temperatures of thermal climate and the under- versus over-representation of several identity features—covering both personal attributes and personality characteristics—in populations around the world. To clarify the issue, take the attribute of gender. If men were to be more cold-blooded and less warm-blooded than women, there would be an under-representation of men and an over-representation of women toward the tropical equator. Obviously, and luckily, that is not the case. Now take creativity as an important component of the personality characteristic of openness to experience. As detailed later, the density of Nobel laureates, technological pioneers, and innovative entrepreneurs increases toward both the North Pole and the South Pole. It seems hard to make sense of this intriguing anomaly without taking into account the spatial severity of cold and hot seasons.

The core idea is the alternating exposure of all living species to heat radiation from space. Only because the Earth spins around its tilted axis toward the Sun, do we escape being frozen in a darkened hemisphere with eternal winter or being burned in a lightened hemisphere with eternal summer. The superimposed idea is that too little, just enough, and too much heat from the Sun leave imprints on sets of identity features but that the size and shape of these imprints are usually dependent upon the economic wealth resources available for handling cold and heat. The resulting population differences have been variously labeled as modal needs (McClelland, 1961), national character (e.g., Inkeles, 1997), and cultural syndromes (Triandis, 1995). The term cultural identity, used here, refers more adequately to both passive adaptation and active niche construction and rests on the more solid foundation of the social identity theory (see Smith & Easterbrook, Chapter 6 in this volume).

The section right after this introduction illustrates briefly how all populations, poor or rich, have automatically adapted a few aspects of their cultural identity to climatic cold and heat. The next section incorporates poverty-based and wealth-based reactions to cold and heat into this line of empirical research. Cultural identities are expected to differ in response to appraisals of climato-economic habitats as being threatening, unthreatening, unchallenging, or challenging. Three main sections then review evidence of general climato-economic pressures on the prevalence of collectivists and individualists and more specific pulls away from and pushes toward fearfulness, trustfulness, tight behavior, and creative behavior. Negative impacts of threatening habitats on creativity and positive impacts of challenging habitats on creativity are reported here for the first time.

ILLUSTRATIONS OF AUTOMATIC ADAPTATIONS TO COLD AND HEAT

Genetic Adaptation: Lactase Persistence

Newborns produce the enzyme lactase needed to metabolize lactose, the sugar found in all milk. However, as the baby matures and begins consuming increasing amounts of other kinds of food, its body gradually decreases the production of lactase and tolerance of lactose (C. J. Cook, 2014; Curry, 2013; Durham, 1991). Intriguingly, the strength of this universal inclination to reduce milk consumption with age varies across the globe, ranging from small reductions by Icelanders and Finns to large reductions by Liberians and Cambodians (FAOSTAT, 2014). Decades of genetic research and academic debate have led to the insight that inhabitants of rather cold habitats and of some hot habitats share phenotypic tolerance of lactose and non-fermented milk products, but do so on the basis of different forms of genotypic lactase persistence (Gerbault, Moret, Currat, & Sanchez-Mazas, 2009; Ingram, Mulcare, Itan, Thomas, & Swallow, 2009).

Specifically, distinct lactase gene variants have been identified for populations in the cold regions of North-Western Europe (−13,910 C/T), and in some hot regions scattered across Northern Africa (−14,010 G/C) and Southern Asia (−13,915 T/G). The current understanding is that North-Western Europeans have evolved the habit of milk drinking to compensate for deficiencies of vitamin D3 and calcium due to insufficient doses of ultraviolet-B radiation from the Sun at colder latitudes (Durham, 1991; Flatz & Rotthauwe, 1973; Gerbault et al., 2009; Itan, Powell, Beaumont, Burger, & Thomas, 2009; Simoons, 2001). For several African and Asian populations in hot and arid areas, by contrast, milk stands out as an uncontaminated and healthy fluid for drinking supported by different gene expressions (G. C. Cook & Al-Torki, 1975; Ingram et al., 2009). Even if these somewhat speculative calcium-absorption and arid-climate explanations are incorrect, we can still be confident that lactase persistence is a genetic adaptation to climatic cold and heat.

Linguistic Adaptation: Speech Sonority

With a view to thermoregulation, it is functional to keep our mouths shut in cold environments and open our mouths in hot environments (Parsons, 2003). Relatedly, when we talk, we have to open our mouths less for consonants than for vowels. The articulation of consonants is characterized by constriction or closure at one or more points in the breath channel, with heat preservation as a result. But in the articulation of vowels, the oral part of the breath channel is exposed to the air, with heat release as a result. Hence, it would serve thermoregulation if words with many consonants (such as b, g, k, p, t) evolved in colder climates, whereas words with many vowels (such as a, o, u, ie, ee) evolved in hotter climates (Van de Vliert, 2009). Perhaps not surprisingly, that is exactly what anthropologists have found.

Fought, Munroe, Fought, and Good (2004) investigated approximately 45,000 word sounds in a sample of 60 indigenous populations chosen to represent major cultural areas on Earth. Each word sound was scored on a 14-point scale ranging from voiceless stop consonant (e.g., p, t, k) to low vowel (e.g., a, ɔ, æ). The resulting sonority score per population was then related to the degree of climatic cold versus heat. In support of the thermoregulatory explanation, the languages manifested more consonant and less vowel usage in colder areas (tchkash, vrazbrod, Gdańsk, Saskatchewan, Vladivostok, etc.) but more vowel and less consonant usage in hotter areas (maraki, tawani, Dahomey, Kuala Lumpur, Paramaribo, etc.). This seems to reflect automatic adaptations to climatic cold and heat rather than deliberate or random creation of languages.

Attitudinal Adaptation: Suicide Inclination

It might seem like a far-fetched idea that climates with severe cold or heat stresses may automatically push some inhabitants over the edge to suicide. Nevertheless, a study of 75 populations from all inhabited continents showed an accelerating increase of suicide rates in countries with colder winters and a steady increase in countries with hotter summers (Van de Vliert, 2009). By far the most suicide-prone populations were found in countries with continental climates where the winters are cold and the summers hot. It is relevant to add that this finding cannot be attributed to lower objective well-being represented by income per head, educational attainment, and life expectancy. Suicidal inclinations in harsher climates are higher among both relatively poor populations (e.g., Kazakhstanis, Lithuanians, and Russians) and relatively rich populations (e.g., Finns, Slovenes, and Swiss).

WEALTH-BASED REACTIONS TO COLD AND HEAT

The Fallacy of Climatic Determinism

Historical settlement patterns away from arctics and deserts, as well as automatic adaptations to thermal climate, tell the incomplete and in fact painfully misleading story that climate determines who we are. For more than 25 centuries, scientists have told that story over and over again (Feldman, 1975; Jankovic, 2010; Sommers & Moos, 1976). Ibn Khaldun, for example, observed that “the more emotional people were in the warmer climes with the prudes in the frigid North” (Harris, 1968, p. 41). At the beginning of the 20th century, proponents of the geographical school similarly argued how climate determines who we are and what we do (Sorokin, 1928; Tetsuro, 1971), sometimes with horrifying overtones of the superiority of some races and inferiority of others (Huntington, 1945; Taylor, 1937).

As so often, the psychological truth is more complex. It is an undeniable fact that colder winters and hotter summers entail larger deviations from physiological homeostasis, fewer nutritional resources, greater health problems, and shrinking control over everyday life. It is also true that more extreme ambient temperatures lead to cognitive cold and heat demands, affective cold and heat stresses, and conative attempts to cope with or manage cold or hot places of residence. But it is a terribly mistaken idea that humankind has no other option than adapting passively to a fixed climatic habitat. On the contrary, humans are quite resistant to climatic change as is apparent from the negligible effect of acclimatization through long-term adjustment in anatomy and physiology (Parsons, 2003). Even more importantly, our ancestors have created not only a rainbow of counteractions against climatic problems and difficulties but also, and especially, valuable property and money as tools that can help construct our own cultural identities (Van de Vliert, 2009, 2013a).

As far as I can ascertain, Montesquieu (1748/1989) was the first to realize how important property and money are for acquiring thermal comfort, nutrition, and health—which I regard as a solid foundation for person formation and development. The scientific breakthrough formulated by Montesquieu is the insight that people predominantly turn wealth resources into goods and services that satisfy climate-related existence needs. Basically, Montesquieu saw a harsh climate as posing a crucially demanding and stressful livability problem and national wealth as a proxy for the availability of resources to tackle that problem. During human evolution, family property, liquid cash, and illiquid capital have very slowly but surely come to serve as major tools for turning a given climatic habitat into a climato-economic habitat that is home to a cultural identity.

The Climato-Economic Interaction

Nowadays, everyone everywhere is handling bitter winters or scorching summers through property-based operations. Money is particularly useful because it can be flexibly moved across goods and services, buyers and sellers, places and times. Owning, earning, saving, and trading can help prevent and dispel discomfort, hunger, thirst, and illness in cold and hot areas and seasons. Economic modeling of climatic cold and heat as cost-raising factors (Burke, Hsiang, & Miguel, 2015; Jankovic, 2010; Rehdanz & Maddison, 2005; Welsch & Kuehling, 2009) leads to the conclusion that both colder-than-temperate winters and hotter-than-temperate summers generate less income (Burke et al., 2015) and are more expensive (Van de Vliert, 2013b). As a rule, economic wealth resources can provide all the necessities of life in these more stressfully demanding seasons, including heat and cold, food and drink, cure and care. Articulating the way that this is visible in modern communities, families in richer countries spend up to 50% of their household income on climate-compensating goods and services, a figure that rises up to 90% in poorer countries (Parker, 2000, pp. 144–147).

A central tenet of climato-economic theorizing is that the same degree of climatic cold or heat can be appraised as either negatively or positively demanding and stressful, that is, as either threatening or challenging depending upon the economic wealth resources available for handling cold and heat (Van de Vliert, 2009, 2013a). The greater economic costs of living in colder or hotter places evoke stronger threat appraisals in case of poverty but stronger challenge appraisals in case of wealth. To clarify and specify how this climato-economic interaction works, it helps to think about the two underlying dimensions as providing from few to many resources. The climatic dimension ranges from few nutritional and health resources (demanding) to many nutritional and health resources (undemanding). The economic dimension ranges from few cash and capital resources (poor) to many cash and capital resources (rich). A two-by-two conceptualization of the climato-economic space then results in four prototypical circumstances of livability. Habitats can be understood as being threatening (demanding, poor), unthreatening (undemanding, poor), unchallenging (undemanding, rich), or challenging (demanding, rich).

Threatening Habitats

In poverty-stricken circumstances, both colder-than-temperate winters and hotter-than-temperate summers loom dangerous because of a dearth of adequate shelter, heating or cooling devices, and seasonal availability of food and water. On top of this, health emergencies persistently lurk around every corner. Cold climates lead to frostbite, pneumonia, asthma, rheumatism, gout, influenza, and common colds, often with sickness absence from work as a further consequence. And in the tropics, there are “major vector-borne diseases (malaria, yellow fever, schistosomiasis, trypanosomiasis, onchocerciasis, Chagas’ disease, filariasis, among others), in which animals that flourish in the warm climate, such as flies, mosquitoes, and mollusks, play the critical role of intermediate hosts” (Sachs, 2000, p. 32). In short, the future is full of uncertainties and frequently beyond control.

A climato-economic habitat appraised as threateningly demanding and stressful is thought to elicit cohesiveness and solidarity in primary groups. Collectivism is functional in dealing with a living environment that arouses negative emotions of fear and distrustfulness and that is perceived as leading to failure with a shortage of strategies to overcome all the livability problems (see also Murray & Schaller, Chapter 4 in this volume). Additionally, goal setting may be primarily driven by a desire for avoiding ambiguity and risks in order to stay in control, leading to tight behavior and cultural outcomes that are typically characterized by rigid rules and roles (for a more detailed account, see Gelfand, Harrington, and Fernandez, Chapter 8 in this volume) and social inequality (Van de Vliert, 2009, 2013a).

Unthreatening Habitats

In areas with more temperate winters and summers, such as those where Comorans and Hondurans live, poverty is not necessarily threatening because climatic resources can make up for the lack of wealth resources. In addition to thermal comfort, temperate climates offer abundant food resources owing to the rich flora and fauna and fewer risks of unhealthy weather conditions. Inhabitants have little reason to worry about future temperatures and nutrition or to fear illnesses that are directly or indirectly linked to excessive cold or heat; in further consequence, they also have little inclination to pursue collectivist goals.

A climato-economic habitat appraised as unthreatening is expected to elicit relaxation and to be perceived as leading to success without much individual or collective effort because livability problems can be overcome easily. There are few pulls away from and pushes toward ingroup cohesiveness and solidarity and few pressures to control negative emotions and to tightly regulate behavior. Against this background, it should perhaps not be surprising that inhabitants of unthreatening habitats are less suicide-prone than inhabitants of colder and hotter habitats, irrespective of whether these other populations are poor or rich (Van de Vliert, 2009).

Unchallenging Habitats

If the inhabitants of an unthreatening habitat grow wealthier and healthier, they run into the paradoxical problem of missing the challenges of stressfully demanding cold and heat. At the very least, they simply have too few weather-related needs for goods and services to use their property for or to spend their money on. By far the best description of unchallenging habitats has been provided by John Steinbeck when he wrote: “I’ve lived in good climate, and it bores the hell out of me.” Tourism may make matters worse. Hordes of tourists, who shun not only climates that are too cold or too hot but also poverty, prefer such unchallenging holiday destinations (Bigano, Hamilton, & Tol, 2006), thus reducing local challenges even further.

A climato-economic habitat appraised as unchallenging may well elicit boredom rather than personal alertness and foresight and be experienced as leading to nowhere because stimulating livability problems are absent or minimal. As a rule, the living environment offers few individual hazards and hurdles, let alone collective tests and trials, and evokes few feelings outside of one’s comfort zone. It may indeed seem paradoxical, but richer populations in temperate climates, who already have all the climatic and economic resources for which they could possibly dream, tend to be unhappier than poorer populations in such climates (Van de Vliert, 2009).

Challenging Habitats

Colder-than-temperate winters and hotter-than-temperate summers, lacking the climatic resources of temperate areas, are inevitably more demanding and stressful. Wealth resources, however, can turn these stressful demands into challenges rather than threats, enabling inhabitants to also survive and thrive in rather harsh climates. Cash and capital can gratify all basic needs by means of special clothing, housing, air-conditioning, household energy, a higher caloric intake in cold climates or more intake of water and salt in hot climates, storage of food, medication, care and cure facilities, specific employer-employee arrangements, and other supplies and accommodations. Although the future is full of uncertainties, it can effectively and satisfactorily be managed.

In consequence, a climato-economic habitat appraised as challengingly demanding and stressful is thought to elicit opportunities for tests of ability and creativity, tests that can commonly be passed by individuals without enlisting much help from family members or others. This kind of living environment tends to come with experiences of curiosity and imagination, positive emotions of trust and fearlessness, and chances for further personal growth. More often than not, goal setting might be driven by a desire for seeking ambiguity and risks in order to create something new, producing cultural outcomes that are typically characterized by regulatory flexibility and social equality.

The Climato-Economic Measures

Assessing Cold and Heat

In climato-economic theorizing and research, 22° Celsius (~72° Fahrenheit) has been adopted as a point of reference because 22° Celsius is the approximate midpoint of the thermoneutral zone, where the experienced pulls and pushes of cold or heat are minimal (Cline, 2007; Gailliot, 2014; Parsons, 2003; Tavassoli, 2009). Climates are less resourceful and more demanding and stressful and require more conscious and subconscious adaptations and other reactions, to the extent that their winters are colder than 22° Celsius, their summers are hotter than 22° Celsius, or both.

Accordingly, climate is measured across a habitat’s major cities, weighted for population size, as degrees of deviation from 22° Celsius in centigrades. Specifically, cold demands are the sum of the downward deviations from 22° Celsius for the average lowest and highest temperatures in the coldest month and the average lowest and highest temperatures in the hottest month; heat demands are the sum of the upward deviations from 22° Celsius for these four average temperatures (source: Van de Vliert, 2013c; downloadable from www.rug.nl/staff/e.van.de.vliert by clicking on Projects). In Sudan, for example, where the lowest and highest temperatures are 5° and 19° Celsius in the coldest month and 40° and 48° Celsius in the hottest month, the cold demands are (│5°C − 22°C│ + │19°C − 22°C│) = 20, the heat demands are (│40°C − 22°C│+│48°C − 22°C│) = 44, and the total score for thermal demands is 64. Total scores are used in what follows here.

Assessing Wealth Resources

Because the impact of thermal demands on communal culture is altered by collective cash and capital (i.e., wealth), independent countries and dependent territories for which collective wealth is known are used as units of analysis. In most studies reported below, wealth is measured as income per head, as the capacity of a country’s currency to buy a given basket of basic goods and services (in international dollars, log transformed to reduce the skewed distribution). However, income per head is in yens for Chinese provinces and in American dollars for states of the United States. Although income per head is in constant flux, its international distribution used as a predictor variable is surprisingly stable (e.g., r = .77, n = 101, p < .001 over the past two centuries).

The Predicted Pressures

As is summarized in Table 5.1, climato-economic theorizing (Van de Vliert, 2009, 2013a) emphasizes the existence of three typical pressures on cultural identity, which are supported in the remainder of this chapter. On the one hand, inhabitants of threatening habitats, where extreme temperatures are insufficiently matched by wealth resources, eventually develop a collectivist identity, as well as over-representations of feelings of fear, and preferences for risk aversion and tightly controllable behavior. On the other hand, inhabitants of challenging habitats, where extreme temperatures are sufficiently matched by wealth resources, eventually develop an individualist identity, as well as over-representations of feelings of trust, and preferences for risk seeking and loosely structured creative behavior. In between, inhabitants of unthreatening and unchallenging habitats tend to develop neither collectivist nor individualist identities, and no under- or over-representations of fear or trust, or preferences for tightness or creativity.

Climato-Economic Habitat |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Thermal climate | Cold or hot | Temperate | Cold or hot |

| Wealth resources | Poor | Poor or rich | Rich |

| Appraisal | Threatening | Unthreatening Unchallenging | Challenging |

| Cognitive identity | Collectivist | Neither | Individualist |

| Affective identity | Fearful | Neither | Trustful |

| Conative identity | Tight behavior | Neither | Creative behavior |

Interestingly, Table 5.1 can be viewed from above and from aside. A vertical reading of the columns interrelates and helps explain cognitive, affective, and conative identities in terms of the ecological interaction of thermal demands and wealth resources. Thus, the columns reflect the explanatory merit of the theory of cultural identity. In addition, a horizontal reading of the rows in Table 5.1 offers systematic descriptions and comparisons of threatening versus challenging habitats in terms of the prevalence of fearful and tight collectivist orientations versus trustful and creative individualist orientations. Thus, the rows reflect the descriptive merit of the theory of cultural identity.

PRESSURES ON COLLECTIVIST AND INDIVIDUALIST IDENTITIES

As small-group animals, by nature humans tend to distinguish between ingroups and outgroups. Owing to climato-economic pressures, however, some are driven more by the primarily cognitive boundaries between their ingroups and outgroups than others. The some we have come to call collectivists, the others we have come to call individualists, and the in-betweens we have come to place on a continuum that connects these opposites (e.g., Gelfand, Bhawuk, Nishii, & Bechtold, 2004; Hofstede, 2001; Oyserman, Coon, & Kemmelmeier, 2002; Triandis, 1995). Treading in the footsteps of Harry Triandis (1995), collectivist versus individualist populations are defined here in terms of the proportions of individuals who are allocentric and idiocentric.

A population has a collectivist identity if there is a smaller proportion or under-representation of idiocentrics and a larger proportion or over-representation of allocentrics—“individuals who see themselves as parts of one or more collectives (family, coworkers, tribe, nation); are primarily motivated by the norms of, and duties imposed by, those collectives; are willing to give priority to the goals of these collectives over their own personal goals; and emphasize their connectedness to members of these collectives” (Triandis, 1995, p. 2). By contrast, a population has an individualist identity if there is an under-representation of allocentrics and an over-representation of idiocentrics—“individuals who view themselves as independent of collectives; are primarily motivated by their own preferences, needs, rights, and the contracts they have established with others; give priority to their personal goals over the goals of others; and emphasize rational analyses of the advantages and disadvantages to associating with others” (Triandis, 1995, p. 2).

For convention, here the term collectivist refers to both individual allocentrics and aggregates of allocentrics, and the term individualist refers to both individual idiocentrics and aggregates of idiocentrics. The most important characteristic is that collectivists are driven stronger by ingroup-outgroup differentiation than individualists are. Because ingroup love and outgroup hate are not necessarily two sides of the same coin (Brewer, 1999), climato-economic theorizing has been put to the test twice, first for preferential treatment of the groups to which one belongs (ingroup favoritism), and then for derogation and subjugation of the groups one does not belong to (outgroup discrimination). Following are reports of two cross-country studies concentrating on ingroup favoritism and outgroup discrimination, respectively, and of a two-country comparison. The last study compares climato-economic imprints on the prevalence of collectivists and individualists among the inhabitants of Chinese provinces and of the states of the United States.

Pressures on Ingroup Favoritism

Theory and Methods

Proliferation of one’s gene pool through advantageous treatment of one’s closest relatives (father, mother, son, daughter, sibling) serves an existential goal (Van de Vliert, 2011). However, genetic survival over time is out of reach if one does not first of all survive extreme temperatures at the place of residence. Thus, from an evolutionary perspective, the advantageous treatment of relatives may also be a natural reaction to climatic threats of cold or heat. This potential confounding of genetic and climatic survival creates a theoretical and methodological complication for research into the origins of ingroup favoritism.

To address that complication, climato-economic pressures on ingroup favoritism have been investigated in three target groups that differ in genetic relevance. My research team considered preferential treatment of members of the nuclear family (familism), relatives at large (nepotism), and fellow nationals (compatriotism). Middle managers’ participative observations of values and practices of familism (n = 17,370 from 57 countries), top executives’ judgments of nepotism (n = 10,932 from 116 countries), and citizens’ self-reported norms of compatriotism (n = 104,861 from 73 countries) have been analyzed (Van de Vliert, 2011). The composite index (Cronbach’s α = .89; Van de Vliert & Postmes, 2012) has also been regressed on thermal demands, wealth resources, and their interaction.

Results and Discussion

As predicted, familism, nepotism, and compatriotism are all over-represented among inhabitants of threatening habitats (e.g., Kazakhstanis and Mongolians), intermediately prevalent among inhabitants of unthreatening and unchallenging habitats (e.g., Guyanese and Taiwanese), and under-represented among inhabitants of challenging habitats (e.g., Icelanders and Americans). Thermal demands (4%), wealth resources (33%), and their interaction (10%) account for 47% of the variance in the composite index of ingroup favoritism, which appears to peak in poor countries with cold winters and hot summers. No evidence surfaced that the results were an epiphenomenon of the impact of parasitic diseases (Van de Vliert & Postmes, 2012), state antiquity, language diversity, ethnic heterogeneity, religious heterogeneity, or income inequality (Van de Vliert, 2011).

Pressures on Outgroup Discrimination

Theory and Methods

In the face of shared threat, identification and interdependence with ingroups tend to be directly associated with fear and hostility toward one or more outgroups (Brewer, 1999). As a likely consequence, ingroup favoritism and outgroup discrimination may both be most prevalent in threatening habitats, intermediately prevalent in unthreatening and unchallenging habitats, and least prevalent in challenging habitats. This further expectation has been supported in an 85-country study about discrimination against neighbors of a different race, immigrants, homosexuals, AIDS patients, and criminals (Van de Vliert, 2013a; Van de Vliert & Yang, 2014). The average of these five internally consistent indicators (Cronbach’s α = .79) has been regressed on the climato-economic predictors.

Results and Discussion

Thermal demands (2%), wealth resources (35%), their interaction (5%), and ingroup favoritism as a control variable (4%) account for 46% of the cross-national variation in outgroup discrimination. People who derogate and subjugate outgroup neighbors are over-represented among inhabitants of threatening habitats (e.g., Azerbaijanis and Belarusians), intermediately prevalent among inhabitants of unthreatening and unchallenging habitats (e.g., Indonesians and Singaporeans), and under-represented among inhabitants of challenging habitats (e.g., Canadians and Swedes). However, when ingroup favoritism is first controlled for (33%), the climato-economic interaction term (1%) does not reach significance anymore, indicating that ingroup favoritism mediates the joint effect of thermal demands and wealth resources on outgroup discrimination. Apparently, climato-economic pressures on collectivist and individualist identities leave direct imprints on ingroup favoritism and only indirect imprints on outgroup discrimination.

Pressures on Chinese and American Identities

Theory and Methods

These cross-country findings clearly suggest that larger under-representations of individualists and over-representations of collectivists in more threatening habitats contrast with larger under-representations of collectivists and over-representations of individualists in more challenging habitats. Similarly, within the large and predominantly poor country of China, which is home to collectivists in threatening and unthreatening habitats, the under-representation of individualists and the over-representation of collectivists is expected to increase in more threatening climatic habitats. By contrast, within the large and predominantly rich country of the United States, which is home to individualists in unchallenging and challenging habitats, the under-representation of collectivists and the over-representation of individualists is expected to increase in more challenging climatic habitats. These hypotheses have been scrutinized through a secondary analysis of the results from two separate studies.

In China, my research team administered a 14-item collectivism-individualism questionnaire to 1,662 native Han Chinese, aggregated scores for the 15 provinces in which they lived and worked, and gathered objective data on thermal demands, income per head, population density, and percentage of minorities from publicly available sources (Van de Vliert, Yang, Wang, & Ren, 2013). For the 50 states of the United States, individualism-collectivism scores were taken from Vandello and Cohen (1999); thermal demands across each state’s major cities (source: www.census.gov/compendia/statab) were averaged and then aggregated per state; and state-level indicators of income per head, population density, and percentage of minorities were retrieved from the same source.

Results and Discussion

The results confirmed the hypotheses, also after controlling for population density and percentage of minorities (for details, see Van de Vliert, 2013a). Within China, greater thermal demands in northern provinces (e.g., Inner Mongolia and Heilongjiang) are associated with more ingroup favoritism than in the temperate climates of southern provinces (e.g., Fujian and Guangdong) (r = .86, p < .001). Multilevel analysis of the individual-level data further showed that ingroup favoritism is stronger in poorer Chinese provinces with more stressfully demanding thermal climates, that is, in more threatening habitats. Within the United States, greater thermal demands in northern states (e.g., Alaska and North Dakota) are associated with less ingroup favoritism than the temperate climates in southern states (e.g., Louisiana and Hawaii) (r = −.72, p < .001). Moreover, these significant opposite tendencies in China compared to the United States are significantly different from each other (z = 6.80, p < .001).

These supplementary results allow four firm conclusions about where collectivists and individualists can be typically found. First, the larger over-representation of collectivists in more threatening climato-economic habitats even holds across regions within China, which is home to the largest collectivist civilization on Earth. Second, the larger over-representation of individualists in more challenging climato-economic habitats even holds across regions within the United States, which is home to the largest individualist civilization on Earth. Third, the within-country replications of the between-country results minimize rival explanations of the geographic spread of collectivists and individualists in terms of genetic makeup, historical factors other than the climatic and economic past, language differences, religious heritage and diversity, educational and political regimes, and the like. Fourth, the opposite latitude-identity tendencies within two countries with similar latitudes do not support strongly latitude-related causes of cultural identity including magnetic field, daylength variation, average temperature level, seasonal cycle, and parasitic disease burden.

PRESSURES ON FEAR AND TRUST

A fearful person may not always be distrustful, and a trustful person may not always be fearless. At the population level, however, it may become virtually impossible to make a meaningful distinction between a fearful and a distrustful cultural identity on the one hand and between a trustful and a fearless cultural identity on the other hand (Gheorghiu, Vignoles, & Smith, 2009; Hofstede, 2001; Kong, 2013, 2015; Welzel & Delhey, 2015; Yamagishi & Yamagishi, 1994). Nevertheless, taking care not to mistake fear for the opposite of trust, climato-economic pressures on fearfulness are here discussed separately from climato-economic pressures on trustfulness.

Pressures on Fearfulness

Theory and Methods

Persistent threats come with many negative affective consequences, which may in the long run lead to illness (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984; Selye, 1978), and there is no reason to believe that climato-economic threats would be an exception. This section focuses on psychosomatic ill-being as an affective manifestation of cultural identity that is the opposite polarity of the luxury problem of having stressful challenges. Published individual-level scores of nonclinical adults on the General Health Questionnaire, the Maslach Burnout Inventory, the Spielberger State-Trait Inventory, and the Beck Depression Inventory were meta-analytically compiled by Fischer and Boer (2011) and by Van Hemert, Van de Vijver, and Poortinga (2002).

Ron Fischer and I then averaged the previously aggregated scores for perceived ill health, burnout, anxiety, and depression into a country indicator of neurotic mental disorder (Cronbach’s α = .67; Fischer & Van de Vliert, 2011), here approximately representing fearfulness. After normalized scores were averaged, data from 58 populations were available for comparison in light of the theoretical framework in Table 5.1. We tested the climato-economic hypothesis by entering mean-centered main effect terms for thermal demands and wealth resources in the first two steps of a hierarchical regression analysis, followed by the interaction term in the third step.

Results and Discussion

We found that thermal demands (0%), wealth resources (17%), and their interaction (21%) account for 38% of the variation in fearfulness. Perceived ill health, burnout, anxiety, and depression appear to be most prevalent in poor populations residing in climates with stressfully demanding winters or summers (e.g., Iranians and Serbs), somewhat prevalent in populations residing in temperate climates irrespective of income per head (e.g., Hong Kongers and Sri Lankans), and least prevalent in rich populations residing in climates with demanding winters or summers (e.g., Finns and Swiss).

China, Singapore, Serbia, and Montenegro were potential outliers. However, when we repeated the analysis after removing these countries, the interactive impact of thermal demands and wealth resources on fearfulness increased from 21% to 27%, making the results clearer rather than fuzzier. The over-representation of fearful ill-being in threatening habitats, the over-representation of fearless well-being in challenging habitats, and the intermediate levels of prevalence in unthreatening and unchallenging habitats are in elegant agreement with the theoretical storyline for climato-economic pressures on affective cultural identity in Table 5.1.

Parasitic disease burden (Fincher & Thornhill, 2012; Schaller & Murray, 2008, 2011) and income inequality (Wilkinson & Pickett, 2009) are known antecedent conditions of stressful cultural fears and suspicions. However, controlling for these rival predictors did not wipe out the climato-economic effects. Because we were relying on a relatively small sample of populations, we also ran a bootstrap analysis but found no indication that the results were due to spurious correlation or outliers (Fischer & Van de Vliert, 2011). Finally, we failed to generate evidence of reverse causation (i.e., that healthier and happier populations construct more beneficial climato-economic niches).

Pressures on Trustfulness

Theory and Methods

Often there are no words to trust or distrust at all. Believing that other people are honest or loyal and have no intention of harming you is usually more a feeling than a thought. The positive emotion of trusting other people, no matter whether those others are members of ingroups or outgroups, provides the trust-senders as well as the trust-receivers with social capital (Fukuyama, 1995; Herreros, 2004; Welzel & Delhey, 2015). “Social capital increases as the radius of trust widens to encompass a larger number of people and social networks among whom norms of generalized reciprocity are operative” (Realo, Allik, & Greenfield, 2008, p. 447). Generalized interpersonal trust—and social capital in its wake—might be considered a societal asset that can help inhabitants manage not only cold or hot habitats but also numerous other demands and stresses of daily life.

Kong (2013), who was the first to explore the untrodden territory of climato-economic precursors of trust, discovered that generalized interpersonal trust as part of cultural identity is higher in challenging habitats than in unchallenging, unthreatening, and threatening habitats. Greater tolerance for uncertain or unknown outcomes appeared to mediate this relationship between more challenging habitats and higher trustfulness. A follow-up study (Kong, 2015) further revealed that this pattern of results is gene dependent. The positive impact of challenging habitats on trust, mediated by tolerance for ambiguity, is stronger in populations that are likely to have higher challenge appraisals of environmental stressors due to lower levels of 5-HTTLPR S-allele prevalence.

Because Kong’s research was based on cross-sectional data from only 67 countries, Robbins (2015) designed and executed a more comprehensive longitudinal study that included representative data from 123 populations spread over a 29-year time period. Trustfulness was measured with the question, “Generally speaking, would you say that most people can be trusted or that you need to be very careful in dealing with people?” The percentage of a country’s population that chose “most people can be trusted” was used as the dependent variable. Data were drawn from the Afro Barometer, the Arab Barometer, the Asian Barometer, the Euro Barometer, the European Values Study, the Latino Barometer, and the World Values Surveys. Unbalanced random-effects models and ordinary least squares regression demonstrated that thermal demands and wealth resources interacted in their impact on generalized interpersonal trust, even after controlling for Nordic habitat, monarchical government, and communist past.

Results and Discussion

An interesting first observation was that 86% of the variation in trustfulness is due to between-country factors (time-invariant pressures such as climatic, economic, and other endpoints of historical trajectories), while only 14% of the variation is due to within-country changes (time-variant pressures such as economic development and political changes). Given that trusting other people is a building stone of interpersonal negotiation and conflict management, organizational development, economic transactions, public governance, and numerous other cultural features (Bachman, 2011; Colquitt, LePine, Piccolo, Zapata, & Rich, 2012; Gunia, Brett, Nandkeolyar, & Kamdar, 2011; Kong, 2013, 2015; Realo et al., 2008), this finding emphasizes the importance of ecological explanations of the evolution of cultural identities.

Depending on the modeling technique used, thermal demands plus wealth resources (24% to 29%), their interaction (8%), and the control variables (14% to 16%) account for 46% to 53% of the cross-national variation in trustfulness. Replicating Kong’s (2013) results, Robbins (2015), too, came to the conclusion that only the inhabitants of challenging habitats develop mutual trust on a broad scale. Thus, the climato-economic pressures on cultural identity seem to be less pronounced for trustfulness than they are for fearfulness. Fearfulness is able to mark its over-representation in threatening relative to unthreatening habitats, as well as its under-representation in challenging relative to unchallenging habitats. Trustfulness, however, is only able to one-sidedly mark its over-representation in challenging relative to unchallenging habitats. There is not the slightest indication that the inhabitants of threatening and unthreatening habitats differ in how much they trust their fellow locals.

PRESSURES ON TIGHTNESS AND CREATIVITY

Humankind also evolves cultural identities by reacting to climatic and economic pulls and pushes on tight behavior and creative behavior. A short recapitulation of the lengthy story in this chapter may help ensure that the additional information to be provided about climato-economic pressures on tightness and creativity does not become confusing. My main line of argument started with heat radiation from the Sun. The Earth’s rotation around its tilted axis toward the Sun produces seasonal cycles with downward deviations from 220 Celsius in some regions and upward deviations from 220 Celsius in other regions. Although this has led to a few automatic adaptations to atmospheric cold and heat, climatic determinism is a major scientific fallacy. Rather, inhabitants manage their reduced control over everyday life in cold and hot habitats by building a collectivist identity embedded in feelings of fear if they are poor but an individualist identity embedded in feelings of trust if they are rich.

Collectivists coping with threat appraisals, sharp boundaries between ingroups and outgroups, and feelings of fear and distrustfulness do not seem to qualify as gifted constructors of creative courses of action and interaction. Mirrorwise, individualists facing challenge appraisals, smooth boundaries between groups, and feelings of trust and fearlessness do not seem to qualify as gifted constructors of tight rules, roles, and behaviors, allowing them to get and stay in control. Climato-economic theorizing accords with common sense in predicting that tightness and creativity are not on friendly terms. Tightness aims to control and maintain established practices that creativity strives to break away from (Van de Vliert, 2009). In consequence, threatening habitats tend to trigger tight behavior at the expense of creativity, whereas challenging habitats tend to trigger creative behavior at the expense of tightness.

Although climato-economic theorizing seems to be unique in asserting that climatic hardships in concurrence with economic hardships promote collectivist identity, this may be largely a matter of specification in presentation. Richter and Kruglanski (2004, pp. 115–116) have professed earlier that existential threats set in motion processes of culture building in directions of closed-mindedness, ingroup commitment, and ingroup favoritism, whereas the opposite processes endow people with a high enough degree of open-mindedness “to venture out on their own into the ambiguous, uncertain, and often risky realm of individualism.” In a similar vein, Gelfand et al. (2011; Harrington & Gelfand, 2014; for the most recent overview, see Chapter 8 in this volume) have provided evidence that greater environmental threats and a greater dearth of resources promote cultural tightness with clearer norms and stronger sanctions for non-conformity, traits that are also highly characteristic of collectivist identity (Carpenter, 2000; Triandis, 1995).

Pressures on Tight Behavior

Theory and Methods

When confronted by a threatening loss of control over their environment, people will at first attempt to reestablish that control (Gelfand et al., 2011; Richter & Kruglanski, 2004; Wortman & Brehm, 1975), using cash and capital as major tools to do so. To the extent that wealth resources are lacking, as is the case in more threatening climato-economic habitats, the key control mechanisms of uncertainty avoidance by formalization and centralization may often serve as back-up tools (Kong, 2013, 2015; Van de Vliert, 2009, 2013a). More formalization ties inhabitants more securely to behavioral prescriptions that guide and control activities and outcomes. More centralization places the power of decision making and control in the hands of fewer people higher up in the hierarchy. Formalization and centralization in combination lead to bureaucratic tightness (for overviews, see Burns & Stalker, 1966; Mintzberg, 1979; Morgan, 1986), which is thought to be increasingly shunned by inhabitants of more challenging climato-economic habitats, who prefer to take their own fate in their own hands.

Survey data gathered among about 17,000 middle managers from over 900 organizations in 61 societies throughout the world (House, Hanges, Javidan, Dorfman, & Gupta, 2004) were analyzed to examine whether tightness varies across threatening versus challenging habitats. The GLOBE group defined formalization or, as these authors named it, uncertainty avoidance as “the extent to which members of collectives seek orderliness, consistency, structure, formalized procedures, and laws to cover situations in their daily lives” (Sully de Luque & Javidan, 2004, p. 603). Centralization or, as these authors named it, power distance was “the degree to which members of an organization or society expect and agree that power should be shared unequally” (Carl, Gupta, & Javidan, 2004, p. 537). Two sets of four 7-point questions tapped formalization and centralization values (for aggregatibility, internal consistency, interrater reliability and construct validity, see Hanges & Dickson, 2004). The two measures were integrated into an index of bureaucratic tightness—the dependent variable in regression analysis.

Results and Discussion

Thermal demands (5%), wealth resources (21%), and their interaction (11%) account for 37% of the variation in bureaucratic tightness. Inhabitants endorsed bureaucratic regulation and control most in threatening habitats (e.g., Iranians and Russians), less in unthreatening and unchallenging habitats (e.g., Filipinos and Taiwanese), and least in challenging habitats (e.g., Austrians and Danes). Supplementary analysis revealed that religious differences and variation in economic activities cannot explain away the findings (Van de Vliert, 2009).

Although the middle managers in this sample function in both superior and subordinate roles, some concern is warranted that superiors rather than subordinates may appreciate tight control behavior. It is therefore important to mention the results of two other studies in which the appreciation of control mechanisms was compared across habitats (Van de Vliert & Postmes, 2012, 2014). Inhabitants of threatening habitats are more satisfied and happier if they are controlled by autocratic governments; inhabitants of challenging habitats are more satisfied and happier under democratic rule. In unthreatening and unchallenging habitats, there is no relationship between the form of government and well-being. In short, unlike populations in challenging habitats, populations in threatening habitats appreciate tight formal rules and hierarchical roles, most likely in order to avoid ambiguity and risks (He, Van de Vliert, & Van de Vijver, in press; Kong, 2013, 2015).

Pressures on Creative Behavior

Theoretical Considerations

Throughout human evolution, stressfully demanding winters and summers have required novel, often ecology-specific, inventions and innovations. Perhaps, then, it should not come as a surprise that the worldwide variation in the prevalence of individual and cooperative creativity is still visible among contemporary inhabitants of threatening versus challenging habitats (Van de Vliert & Murray, 2016). The greater creativity triggered by seasonal challenges in rich populations, compared to seasonal threats in poor populations, presumably has been gradually generalized and sublimated into a wider variety of inventions and innovations as well as higher investments in institutionalized research and development.

As touched upon in the introduction, there are more Nobel laureates, technological pioneers, and innovative entrepreneurs at higher latitudes toward the poles. The best available explanation so far is that disease-causing parasites thrive in warm ecologies toward the equator (Cashdan, 2014; Epstein, 1999) and that the lower disease burden at colder latitudes tends to favor creativity. Murray (2014) has shown that lower prevalence of disease-causing pathogens is robustly associated with higher creativity and that this relationship is mediated by reductions in collectivism and conformity. But how sure is it that lower disease prevalence is not a confounded indicator of stressful cold demands? A preliminary study of the climatic and economic origins of nations’ creativity (Karwowski & Lebuda, 2013) seems to suggest that parasitic pressure is in fact a manifestation of climato-economic pressure.

The apparent geography of creativity makes it interesting to investigate which variable predicts creative behavior the best—parasitic stress or climato-economic stress. This may be more than a matter of effect size because parasitic pressure is qualitatively—and thus theoretically—different from climato-economic pressure. Unlike humans, parasites cannot discriminate between unthreatening and unchallenging habitats in comforting climates, nor can they discriminate between threatening and challenging habitats in stressfully demanding climates. Or, put from another perspective, parasites may be better at undermining rather than underpinning human creativity, whereas wealth resources may be better at underpinning rather than undermining societal invention and innovation (cf. Van de Vliert, 2013c; Van de Vliert & Postmes, 2012).

Refined Prediction

The climato-economic pressures and predictions in Table 5.1 make no distinction between unthreatening and unchallenging habitats. It would therefore be a great step forward if an over-representation of creativity could be shown in unchallenging vis-à-vis unthreatening habitats. Throwing all caution in the wind, I predicted that creative attitudes and behaviors are increasingly prevalent in threatening, unthreatening, unchallenging, and challenging habitats, in this order.

Cultural Creativity

Murray’s (2014) worldwide measures of invention and innovation allowed us (Van de Vliert & Murray, 2016) to construct a 155-country index of creativity based on data from different sources employing different research methods including unobtrusive measures, official observations, and subjective survey responses. Cultural creativity was represented by (a) rates of Nobel Prize laureates per country of birth, (b) the technology index of the United Nations, (c) country rates of patent applications from the World Intellectual Property Organization, (d) Cornell University’s global innovation index, and (e) a measure of innovation versus invention from the World Economic Forum. Care was taken to verify the internal consistency of the index (.64 < r < .92), its representativeness (.85 < r < .96), and the equivalence of its meaning across cultures (.64 < r < .93).

Control Variables

The first variable entered into the regression analysis was the prevalence of human-to-human transmitted or non-zoonotic parasitic diseases (e.g., measles, cholera, leishmaniasis, and leprosy). This particular index, compiled by Fincher and Thornhill (2012), was chosen as these non-zoonotic diseases are preeminently the ones that motivate people to avoid potentially infectious contacts with others, thus inhibiting social network structures that are conducive to creativity. Non-zoonotic diseases served as a competitive predictor because disease-causing pathogens are known to reduce invention and innovation (Murray, 2014).

Current points of historical trajectories of national IQ, industrialization, and urbanization were also controlled for as these processes are so entwined with increasing material wealth that they might unintentionally confirm the refined prediction. National IQ (Lynn, 2007)—the average intelligence of a country’s inhabitants relative to other countries’ inhabitants—is available from Lynn and Vanhanen (2006). Industrialization (UNDP, 2004, 2007) is each country’s position on the historical continuum from agriculture to industrial and service employment (based on national percentages of employment in the three sectors). Urbanization (Parker, 1997) is the percentage of the country’s total population living in urban areas.

Regression Results

As can be seen in Table 5.2, lower prevalence of non-zoonotic diseases initially seems to account for 37% of the variation in cultural creativity (model 1) but turns out to be an epiphenomenal effect of the control variables (model 2). National IQ and urbanization together predict 60% of the variation in cultural creativity. Model 3 shows that thermal demands (b = .17, p < .01) and wealth resources (b = .65, p < .001) account for an extra 11% over and above the positive impact of national IQ (b = .02, p < .01). Finally, and most importantly, the interaction of thermal demands and wealth resources also reaches significance (b = .28, p < .001), increasing the effect size from 71% to 77% (model 4).

| Predictor | Model 1 (b) |

Model 2 (b) |

Model 3 (b) |

Model 4 (b) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Non-zoonotic diseases |

−.61*** |

−.09 |

.02 |

.01 |

National IQ |

.03*** |

.02** |

.02*** |

|

Industrialization |

.01 |

−.01 |

.01 |

|

Urbanization |

.01* |

.00 |

.00 |

|

Thermal demands (TD) |

.17** |

.12* |

||

Wealth resources (WR) |

.65*** |

.55*** |

||

TD × WR |

.28*** |

|||

ΔR2 |

.37*** |

.23*** |

.11*** |

.06*** |

Total R2 |

.37*** |

.60*** |

.71*** |

.77*** |

Note. There was no multi-collinearity (VIFs < 6.79), and there were no outliers (Cook’s Ds < .22). *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001. |

||||

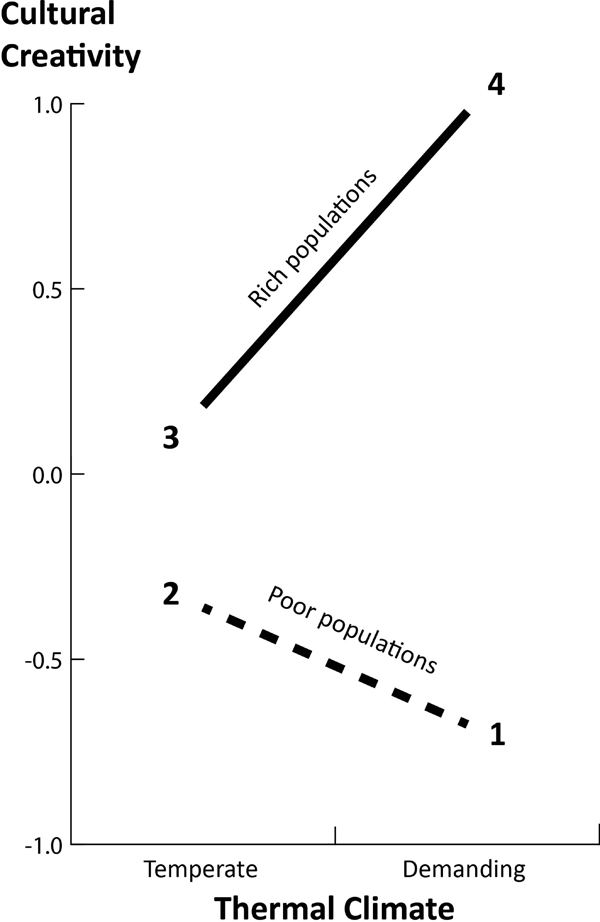

The plot of the climato-economic interaction effect on cultural creativity in Figure 5.1 provides full support for the refined prediction. Nobel laureates, technological pioneers, and innovative entrepreneurs are under-represented in poorer populations, but more so to the extent that these poorer populations reside in threatening habitats. Also, Nobel laureates, technological pioneers, and innovative entrepreneurs are over-represented in richer populations, but more so to the extent that these richer populations reside in challenging habitats. Supplementary analyses suggest that imperfect sampling of small and adjacent countries within the same climatic subzone, and of large countries with different climatic subzones, have biased the results only to a trivial extent.

Discussion

In anticipation of a more thorough publication (Van de Vliert & Murray, 2016), negative pressures of threatening habitats on creativity and positive pressures of challenging habitats on creativity are reported here for the first time. Climatic, economic, and parasitic precursors of cultural creativity appear to be operating in concert rather than in competition as various creativity scholars would have it (e.g., Andersson, Andersson, & Mellander, 2011; Hsiang, Burke, & Miguel, 2013; Murray, 2014; Talhelm et al., 2014). More inventive and more innovative attitudes and activities in less threatening and more challenging climato-economic habitats seem to be driven by local trust and local desires for seeking ambiguity and risks in order to create something new.

The results may be represented as a worldwide climato-economic ladder with stepwise increases in creative behavior. At the least creative first step are strong collectivists residing in threatening habitats (e.g., Chinese in the northern provinces of China). At the second step are weak collectivists residing in unthreatening habitats (e.g., Chinese in the southern provinces of China). At the third step are weak individualists residing in unchallenging habitats (e.g., Americans in the southern states of the United States). And at the most creative fourth step are strong individualists residing in challenging habitats (e.g., Americans in the northern states of the United States).

If Figure 5.1 is a valid representation of reality around the world, climatic and economic changes can both cause upward and downward movements on this ladder of creativity, albeit in completely different ways. The impact of climate change is restricted to smaller changes in creativity between the threat-steps 1 and 2 and larger changes in creativity between the challenge-steps 3 and 4. By contrast, the impact of economic change is restricted to smaller increases or decreases in creativity between unthreatening and unchallenging habitats (steps 2 and 3) and larger increases or decreases in creativity between threatening and challenging habitats (steps 1 and 4).

EVALUATION AND CONCLUSION

Strengths and Weaknesses

The foregoing overview of climato-economic pressures on cultural identity is no exception to the rule that every empirical theory has inherent strengths and weaknesses as a result of the assumptions and methods employed. The strength of going beyond climatic and economic determinism comes with the weakness of only cross-sectional support for the causal relationship between habitats and their inhabitants’ cultural identities. The strength of explaining the geographic spread of cultural identities in terms of threat appraisals versus challenge appraisals comes with the weakness that these appraisals and the underlying gratification of basic needs for thermal comfort, nutrition, and health have not been measured and analyzed. The strength of investigating cognitive identities (ingroup favoritism, outgroup discrimination), affective identities (fearfulness, trustfulness), and conative identities (tight behavior, creative behavior) comes with the weakness of not considering identity features at the individual level (for multilevel evidence in support of the theory in Table 5.1, see Chen, Hsieh, Van de Vliert, & Huang, 2015; Fischer, 2013; Van de Vliert, Huang, & Levine, 2004; Van de Vliert, Yang, et al., 2013).

A Meta-Analytic Comparison

Climato-economic theorizing has been fruitfully applied to investigate multiple domains of human functioning other than the domain of cultural identity (e.g., hypertension, infant mortality, wage importance, and ecosystem protection). A comparison of the effect sizes across studies uncovered that thermal demands account for the largest portion of the variation in critical matters of life or death (e.g., physical health), whereas wealth resources account for the largest portion of the variation in critical matters of work and organization (e.g., work motivation) (Van de Vliert, 2009). Clearly, the above-reported effect sizes are larger for wealth resources than for thermal demands, thus suggesting that the domain of cultural identity is closer to the work-and-organization segment than to the life-or-death segment of human functioning.

More specifically, it is also interesting to compare the relative sizes of the main and interaction effects of thermal demands and wealth resources across studies. In only two cases are the interaction effects larger than the additive main effects. Above we saw that thermal demands (0%), wealth resources (17%), and their interaction (21%) account for 38% of the variation in fearfulness. Elsewhere, it has been reported that, even with the cognitive cultural identity of collectivists versus individualists controlled for, thermal demands (0%), wealth resources (6%), and their interaction (13%) account for 19% of the cross-national variation in “threats of violence or physical abuse or actual abuse” (Van de Vliert, 2013a; Van de Vliert, Einarsen, & Nielsen, 2013). Together, these essentially identical yet independent findings may well point to an over-representation of neurotic personalities in threatening relative to challenging climato-economic habitats.

Next Steps

Stressful cold and heat demands can shape cultural identities in additive or interactive ways, and both have their academic merits (Van de Vliert, 2013b). A related yet insufficiently addressed question is to what extent inhabitants react culturally to cold and heat in general (i.e., to downward and upward deviations from 220Celsius in total) and to what extent they react culturally to specific combinations of climatic cold and heat. The interacting predictive powers of cold and heat deserve attention also because (a) present-day Earth offers more and higher cold demands and stresses than heat demands and stresses (for details, see Van de Vliert, 2013b), (b) warm winters can compensate extremely hot summers, and (c) cool summers can compensate extremely cold winters (for preliminary evidence, see Van de Vliert, 2009; Van de Vliert & Tol, 2014).

Another promising topic for further theory building on the ecological precursors of cultural identities is the integration of climato-economic and parasitic pressures on human functioning. Disease-causing pathogens tend to thrive in warm climates (Cashdan, 2014; Epstein, 1999; Murray, 2013; Talhelm et al., 2014), and wealth resources are often used to control the incidence of these pathogens. As a consequence, parasitic diseases in general and non-zoonotic diseases in particular may in some domains be mediating the impact of threatening, unthreatening, unchallenging, and challenging habitats on cultural identities (for more detailed evidence, see Van de Vliert & Murray, 2016).

Perhaps most importantly, we should stop pitting climatic accounts of personal attributes or personality characteristics against genetic ones. Climatic and genetic explanations are not mutually exclusive. Recall, for example, the evolutionary selection for the ability to digest lactose beyond weaning in populations that had domesticated milk-producing animals in order to survive climatic cold or heat. A natural point of departure for follow-up research might be that climatic survival in a particular place is a necessary but insufficient condition for sexual reproduction and thus for genetic survival and influence over time. In consequence, so-called genetic influences on persons or populations could, in fact, be tacitly mediating between climato-economic pressures and individual or cultural specifics and particulars on the effect side of the causal relationship.

Coda

Year-round heat radiation from space influences communal thinking, feeling, and acting. Reacting to too little or too much heat, poorer populations have evolved a more collectivist identity embedded in threat appraisals, feelings of fear, and tight behavior. Richer populations, however, reacting to those suboptimal heat conditions have evolved a more individualist identity embedded in challenge appraisals, feelings of trust, and creative behavior.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I thank Damian Murray for his cooperation in mapping the climatic, economic, and parasitic pressures on creative culture (Van de Vliert & Murray, 2016) and Tim Church, Boele de Raad, and Peter Smith for their helpful suggestions and critical comments on earlier versions of this chapter.

REFERENCES

Andersson, D. E., Andersson, Å. E., & Mellander, C. (Eds.). (2011). Handbook of creative cities. Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar.

Bachman, R. (2011). At the crossroads: Future directions in trust research. Journal of Trust Research, 1, 202–213.

Bigano, A., Hamilton, J. M., & Tol, R. S. J. (2006). The impact of climate on holiday destination choice. Climatic Change, 76, 389–406.

Brewer, M. B. (1999). The psychology of prejudice: Ingroup love or outgroup hate? Journal of Social Issues, 55, 429–444.

Burke, M., Hsiang, S. M., & Miguel, E. (2015). Global non-linear effect of temperature on economic production. Nature, 527, 235–239.

Burns, T., & Stalker, G. M. (1966). The management of innovation (2nd ed.). London, England: Tavistock.

Carl, D., Gupta, V., & Javidan, M. (2004). Power distance. In R. J. House, P. J. Hanges, M. Javidan, P. W. Dorfman, & V. Gupta (Eds.), Culture, leadership, and organizations: The GLOBE study of 62 societies (pp. 513–563). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Carpenter, S. (2000). Effects of cultural tightness and collectivism on self-concept and causal attributions. Cross-Cultural Research, 34, 38–56.

Cashdan, E. (2014). Biogeography of human infectious diseases: A global historical analysis. PLoS ONE, 9(10), e106752.

Chen, L., Hsieh, J. J. P., Van de Vliert, E., & Huang, X. (2015). Cross-national differences in individual knowledge-seeking patterns: A climato-economic contextualization. European Journal of Information Systems, 24, 314–336.

Cline, W. R. (2007). Global warming and agriculture: Impact estimates by country. Washington, DC: Center for Global Development, Peterson Institute for International Economics.

Colquitt, J. A., LePine, J. A., Piccolo, R. F., Zapata, C. P., & Rich, B. L. (2012). Explaining the justice-performance relationship: Trust as exchange deepener or trust as uncertainty reducer? Journal of Applied Psychology, 97, 1–15.

Cook, C. J. (2014). The role of lactase persistence in precolonial development. Journal of Economic Growth, 19, 369–406.

Cook, G. C., & Al-Torki, M. T. (1975). High intestinal lactase concentrations in adult Arabs in Saudi Arabia. British Medical Journal, 3(5976), 135–136.

Curry, A. (2013). The milk revolution. Nature, 500(7460), 20–22.

Durham, W. H. (1991). Coevolution: Genes, culture, and human diversity. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Epstein, P. R. (1999). Climate and health. Science, 285(5426), 347–348.

FAOSTAT. (2014). Milk available for consumption, in kcal/capita/day. Retrieved from http://faostat3.fao.org/download/FB/FBS/E

Feldman, D. A. (1975). The history of the relationship between environment and culture in ethnological thought: An overview. Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences, 11, 67–81.

Fincher, C. L., & Thornhill, R. (2012). Parasite-stress promotes in-group assortative sociality: The cases of strong family ties and heightened religiosity. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 35, 61–79.

Fischer, R. (2013). Improving climato-economic theorizing at the individual level. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 36, 488–489.

Fischer, R., & Boer, D. (2011). What is more important for national well-being: Money or autonomy? A meta-analysis of well-being, burnout and anxiety across 65 societies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101, 164–184.

Fischer, R., & Van de Vliert, E. (2011). Does climate undermine subjective well-being? A 58-nation study. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 37, 1031–1041.

Flatz, G., & Rotthauwe, H. W. (1973). Lactose nutrition and natural selection. Lancet, 302 (7820), 76–77.

Fought, J. G., Munroe, R. L., Fought, C. R., & Good, E. M. (2004). Sonority and climate in a world sample of languages: Findings and prospects. Cross-Cultural Research, 38, 27–51.

Fukuyama, F. (1995). Trust: The social virtues and their creation of prosperity. New York, NY: Free Press.

Gailliot, M. T. (2014). An assessment of the relationship between self-control and ambient temperature: A reasonable conclusion is that both heat and cold reduce self-control. International Review of Social Sciences and Humanities, 8, 149–193.

Gelfand, M. J., Bhawuk, D. P. S., Nishii, L. H., & Bechtold, D. J. (2004). Culture and individualism. In R. J. House, P. J. Hanges, M. Javidan, P. W. Dorfman, & V. Gupta (Eds.), Culture, leadership, and organizations: The GLOBE study of 62 societies (pp. 437–512). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Gelfand, M. J., Raver, R. L., Nishii, L., Leslie, L. M., Lun, J., Lim, B. C., … Yamaguchi, S. (2011). Differences between tight and loose cultures: A 33-nation study. Science, 332(6033), 1100–1104.

Gerbault, P., Moret, C., Currat, M., & Sanchez-Mazas, A. (2009). Impact of selection and demography on the diffusion of lactase persistence. PLoS ONE, 4(7), e6369.

Gheorghiu, M., Vignoles, V., & Smith, P. B. (2009). Beyond the United States and Japan: Testing Yamagishi’s emancipation theory of trust across 31 nations. Social Psychology Quarterly, 72, 365–383.

Gunia, B. C., Brett, J. M., Nandkeolyar, A. K., & Kamdar, D. (2011). Paying a price: Culture, trust, and negotiation consequences. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96, 774–789.

Hanges, P. J., & Dickson, M. W. (2004). The development and validation of the GLOBE culture and leadership scales. In R. J. House, P. J. Hanges, M. Javidan, P. W. Dorfman, & V. Gupta (Eds.), Culture, leadership, and organizations: The GLOBE study of 62 societies (pp. 122–151). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Harrington, J. R., & Gelfand, M. J. (2014). Tightness—looseness across the 50 United States. PNAS, 111(22), 7990–7995.

Harris, M. (1968). The rise of anthropological theory: A history of theories of culture. New York, NY: Crowell.

He, J., Van de Vliert, E., & Van de Vijver, F. J. R. (in press). Extreme response style as a cultural response to climato-economic deprivation. International Journal of Psychology. doi:10.1002/ijop.12287

Herreros, F. (2004). The problem of forming social capital: Why trust? New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture’s consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions, and organizations across cultures (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

House, R. J., Hanges, P. J., Javidan, M., Dorfman, P. W., & Gupta, V. (Eds.). (2004). Culture, leadership, and organizations: The GLOBE study of 62 societies. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Hsiang, S. H., Burke, M., & Miguel, E. (2013). Quantifying the influence of climate on human conflict. Science, 341(6151). doi:10.1126/science.1235367

Huntington, E. (1945). Mainsprings of civilization. New York, NY: Wiley.

Ingram, C. J. E., Mulcare, C. A., Itan, Y., Thomas, M. G., & Swallow, D. M. (2009). Lactose digestion and the evolutionary genetics of lactase persistence. Human Genetics, 124, 579–591.

Inkeles, A. (1997). National character: A psycho-social perspective. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction.

Itan, Y., Powell, A., Beaumont, M. A., Burger, J., & Thomas, M. G. (2009). The origins of lactase persistence in Europe. PLoS Computational Biology, 5(8), e1000491.

Jankovic, V. (2010). Climates as commodities: Jean Pierre Purry and the modelling of the best climate on Earth. Studies in History and Philosophy of Science, 41, 201–207.

Karwowski, M., & Lebuda, I. (2013). Extending climato-economic theory: When, how, and why it explains differences in nations’ creativity. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 36, 493–494.

Kong, D. T. (2013). Examining climatoeconomic contextualization of generalized social trust mediated by uncertainty avoidance. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 44, 574–588.

Kong, D. T. (2015). A gene-dependent climatoeconomic model of generalized trust. Journal of World Business, 50, 226–236.

Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York, NY: Springer.

Lynn, R. (2007). The evolutionary biology of national differences in intelligence. European Journal of Personality, 21, 733–734.

Lynn, R., & Vanhanen, T. (2006). IQ and global inequality. Augusta, GA: Washington Summit.

McClelland, D. C. (1961). The achieving society. Princeton, NJ: Van Nostrand.

Mintzberg, H. (1979). The structuring of organizations: A synthesis of the research. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Montesquieu, C. d. S. (1989). L’esprit des lois [The spirit of the laws; A. M. Cohler, B. C. Miller, & H. S. Stone (Trans.)]. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. (Original work published 1748.)

Morgan, G. (1986). Images of organization. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Murray, D. R. (2013). Cultural adaptations to the differential threats posed by hot versus cold climates. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 36, 497–498.

Murray, D. R. (2014). Direct and indirect implications of pathogen prevalence for scientific and technological innovation. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 45, 971–985.

Oyserman, D., Coon, H. M., & Kemmelmeier, M. (2002). Rethinking individualism and collectivism: Evaluation of theoretical assumptions and meta-analyses. Psychological Bulletin, 128, 3–72.

Parker, P. M. (1997). National cultures of the world: A statistical reference. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

Parker, P. M. (2000). Physioeconomics: The basis for long-run economic growth. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Parsons, K. C. (2003). Human thermal environments: The effects of hot, moderate and cold environments on human health, comfort and performance (2nd ed.). London, England: Taylor & Francis.

Realo, A., Allik, J., & Greenfield, B. (2008). Radius of trust: Social capital in relation to familism and institutional collectivism. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 39, 447–462.

Rehdanz, K., & Maddison, D. (2005). Climate and happiness. Ecological Economics, 52, 111–125.

Richter, L., & Kruglanski, A. W. (2004). Motivated closed mindedness and the emergence of culture. In M. Schaller & C. S. Crandall (Eds.), The psychological foundations of culture (pp. 101–121). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Robbins, B. G. (2015). Climate, affluence, and trust: Revisiting climato-economic models of generalized trust with cross-national longitudinal data, 1981–2009. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 46, 277–289.

Sachs, J. (2000). Notes on a new sociology of economic development. In L. E. Harrison & S. P. Huntington (Eds.), Culture matters: How values shape human progress (pp. 29–43). New York, NY: Basic Books.

Schaller, M., & Murray, D. R. (2008). Pathogens, personality, and culture: Disease prevalence predicts worldwide variability in sociosexuality, extraversion, and openness to experience. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95, 212–221.

Schaller, M., & Murray, D. R. (2011). Infectious disease and the creation of culture. Advances in Culture and Psychology, 1, 99–151.

Selye, H. (1978). The stress of life. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Simoons, F. J. (2001). Persistence of lactase activity among Northern Europeans: A weighing of the evidence for the calcium absorption hypothesis. Ecological Food Nutrition, 40, 397–469.

Sommers, P., & Moos, R. H. (1976). The weather and human behavior. In R. H. Moos (Ed.), The human context: Environmental determinants of behavior (pp. 73–107). New York, NY: Wiley.

Sorokin, P. A. (1928). Contemporary sociological theories. New York, NY: Harper.

Sully de Luque, M., & Javidan, M. (2004). Uncertainty avoidance. In R. J. House, P. J. Hanges, M. Javidan, P. W. Dorfman, & V. Gupta (Eds.), Culture, leadership, and organizations: The GLOBE study of 62 societies (pp. 602–653). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.