10

Personality, Character, and Cultural Differences: Distinguishing Enduring-Order versus Evolving-Order Cultures

Gerard Saucier

We know that humans differ with respect to personality characteristics. Within any population one finds individual differences with respect to characteristic patterns of behavior, thought, motivation, and affect. And we know that such characteristics tend, particularly in adulthood, to be relatively stable across time. Both the variation and the stability across time are reasonably well mapped by existing empirically based models like the Big Five (Goldberg, 1990) or overlapping alternatives (e.g., Saucier, 2009).

Likewise, we know that humans live in societies that have evidently something understood as culture. This “culture” can be defined as shared ideas, beliefs, worldview, attitudes, values, norms, rules, and standards: shared patterns of thinking that underlie human behavior. There is no human group without a significant cultural domain of shared ideas, beliefs, norms, and so on (Brown, 1991).

Both personality and culture are scientifically well-accepted realities, but the nature of the relation between them is less clear and consensually understood. The weak linkage might be traced to a variety of factors. Prior to the 1960s, anthropology failed to light upon a promising culture-and-personality paradigm due to overcommitment to unproductive conceptual frameworks (e.g., classic Freudian theory, or typological approaches based on unrealistic notions of within-group homogeneity). After the 1960s, the zeitgeist of that field has gone in a different direction. For its part, psychology gave very little attention to cultural matters until 40 years ago, and though growing, cultural psychology remains a peripheralized field in a highly compartmentalized discipline of psychology within which personality and cultural psychologists rarely intersect. Down on the “farm” that is the field of psychology, culture and personality thrive in distinct siloes well separated from one another.

Linking up concepts and paradigms in personality with those of culture is no mere academic exercise. Personality psychology is now a multinational and transcontinental field that can no longer assume that models and nomological networks from Western countries will obediently replicate in other populations, some of which have a much greater share of the world population than does the West. Cultural psychology must come to grips with the reality that to treat “members of a culture” as all alike not only oversimplifies the data, but is a form of stereotyping. Frequently, insights, understanding, and the capacity for downstream applications are lost when knowledge is compartmentalized; reality does not respect disciplinary compartments that are based on the somewhat historically arbitrary divisions that have arisen in academe. One sees (at least) two important problems: How does one understand the structure, sources, and consequences of personality attributes in a way that accounts for what is culturally variant and culturally specific, as well as what is cross-culturally ubiquitous? And does one understand cultural dynamics in a way that takes account of the contributions of individual-level variation?

PRINCIPLES

In the remainder of this chapter, I deal with this issue or problem by advancing a set of 12 interlocking principles that serve to link up the disparate fields of personality and culture. These principles are linked in a series, so the order in which they are presented is far from random. Most of the principles have substantial empirical backing; some of whose empirical support is not yet well-established are advanced because they not only are promising but also help to usefully link those principles that do have clearer empirical backing, bringing more coherence to the overall framework. Along the way, there will be opportunity to comment on pertinent methodological and historical issues, as well as relevant current events.

1. Culture is not just incidental to human life but profoundly important to it: we are cultural animals. On a sheer physical level, humans are less well-equipped to survive in a tooth-and-claw world than their primate cousins; chimpanzees, though smaller, have strength, ferocity, and agility that enable them to defeat humans in hand-to-hand combat. In the course of evolution, humans have traded off body power (muscle strength) for brain power (Bozek et al., 2014), making up for an increasingly underdeveloped physical survival vehicle with an elaborated cultural survival vehicle (Pagel, 2012) with systems of technology, language, and culture. Although other species give evidence of fragmentary cultural learning, among humans this learning is distinct in being rapid, fueled by capacities for wholesale imitation, in being cumulative, and in its facilitation by sophisticated uses of language. Distinctly, human cultures have enforced social norms existing within rule systems—including ethics, morality, rituals, and religion—to which persons demonstrate their specific adherence and allegiance by specific communicative display (Hill, 2009). Given species-wide problems like mass violence and self-induced climate, a sapiens label may be ill-fitting. But there is less doubt that we constitute a Homo culturalis. As Baumeister (2005; also Henrich, 2008) argued, we are cultural animals.

2. Cultural standards center on moral and social norms. Major components of culture identified in the earlier definition—shared values, norms, rules, and standards—suggest the potential importance of morality. These components have long been emphasized by prominent sociologists (e.g., Parsons, 1970, p. 22; Shils, 1975, p. 38) and anthropologists (Kroeber, 1948, pp. 101-102; Linton, 1945, pp. 43-53). Westen (1985, p. 224) saw these very components as constituting a “culture ideal” operative in individual psychodynamics.

There are reasons to agree not only with the broad proposition that “human culture is normative” (Dubreuil, 2010, p. 31) but even with Miller’s (2007) stricter proposition: “Morality is central to culture” (p. 477). Culture frames conceptions of what is normative. And by the definition of being cultural, this is shared knowledge. Coordination with individuals who do not share your social norms is costly (Perry, 2009). There is, however, more than one type of normative frame within a culture (Bailey, 2001). As Hill (2009) suggests, ethical rules (and those conventions that we might term social norms but not moral norms) are quite distinct to human culture, and some of these are backed up by enforcement (via punishment or reward). Thus, moral behavior reflects culturally learned knowledge—about rules and standards with regard to what considered good or bad, right or wrong, selfish or unselfish. As Shweder (1991, p. 191) notes, many routine everyday behaviors (queueing, sharing, dividing things up) are governed by moral interpretations. And as Hill (2009) observes, “many cultural rules encourage individual altruistic behavior that serves the common good and are backed by social punishment” (p. 276), and even rituals and religion yield emotional investment in the continuing maintenance of the moral rule system. Indeed, part of the sanctioning is carried on verbally through application of highly evaluative character/personality language; as Hill (2009) observes, people “experience feelings of anger, fairness, justice, indignation, guilt, and so on and categorize other humans as jerks, assholes, self-centered, egotists, sleazeballs, criminals, villains, and so on when they violate social regulations” (p. 281). People respond to culturally defined violations “as disgusting, revolting, repulsive, vile, abhorrent, deranged, and so on,” whereas one sees “little evidence that primates show similar emotional responses to deviants who fail to adhere to the local socially learned traditions” (p. 281). People only respond with strong emotion when there is something at stake, and these instances of highly affective language imply that many people have a strong stake in the maintenance and observance of the moral rule system.

The most evaluative personality language tends to be about adherence or violation of moral norms. Hampson, Goldberg, and John (1987) presented reliable social desirability norms for 573 personality adjectives. Among those terms administered to both British and American raters, the most evaluatively extreme were Honest, Kind, and Sincere at one pole, and Cruel, Deceitful, Dishonest, and Insincere at the other pole. The content suggests strong verbal sanctioning of deceit and cruelty, across two populations.

The priority of moral contents can also be seen in the culturally relevant domain of values. S. H. Schwartz and Bardi (2001) found, across diverse populations from around the world, surprising consensus in the relative ranking of values. Benevolence values (e.g., being honest, helpful, and forgiving) were at the top of a high-international-consensus values hierarchy. It is widely recognized that moral rules and obligations are naturally given a high priority, as reflected in strong sanctions, capacity to trump other social rules and norms, and applicability to everyone (Wallace & Walker, 1970).

To be clear, morality is not the only concern evident in cultural norms, standards, values, and the like. For example, competence concepts may be just as ubiquitous cross-culturally as are morality concepts (Saucier, Thalmayer, & Bel-Bahar, 2014). And competences are clearly a concern in the variation expressed in personality adjectives (e.g., Intellect; Goldberg, 1990) and type-nouns (Saucier, 2003). They are likely linked to status considerations of a different kind than is true for morality. A broader treatment of cultural standards in relation to individual differences should give a full account of competence standards, but this is beyond the scope of the current chapter, because compared to morality, competence standards seem to have only a secondarily crucial place in the understanding of culture.

Nor should the proposal that morality is central to culture be misunderstood as a claim that a majority portion of culture consists of morality. Culture can be usefully understood as a rather loose association of multitudinous conventions (Poortinga, 2011): these are norms and standards but not necessarily moral ones. Conventions regarding domains as diverse as art, business, education, technology, and even science are all cultural in nature. It is just that moral norms tend to be a highly conserved, consequential, and affectively charged component of culture, giving them a centrality that, as I will argue shortly, bleeds over into the domain of personality differences.

So, to return to our main points: humans are cultural animals, and their cultural norms center—reach their highest evaluative pitch—in the area of moral norms. How does this translate into personality?

3. The central personality dimension is character, that is, the tendency to regulate oneself by those evaluative norms that inspire dutiful action and restraint from pure pursuit of self-interest.The most emphatic evidence for this point comes from studies of type-nouns, which tend to be more evaluative than adjectival descriptors of personality. Saucier (2003) derived factors from the correlations among 372 highly familiar American-English type-nouns from ratings of 607 targets (a mixture of self and liked and disliked targets). What is the center of gravity for this kind of descriptor? Table 10.1 lists the 25 terms with the highest loading on the first unrotated principal component, along with the personologically relevant definition from the American Heritage Dictionary (1991). It is clear that a majority of these domain-central type-nouns have moral content, much of it focusing on deceit (e.g., Weasel, Phony, Fake, Liar, Deceiver, and Crook), and a second major type of content involves incompetence (e.g., Idiot, Moron, Dummy, and Dumbbell). Type-noun structure centers on moral emotions: first, on the issue of whether the target is or is not the elicitor of moral emotions, such as disgust and especially contempt, and second, because subjected to trait-ascriptions like these, the target should feel ashamed (another moral emotion). It appears that a substantial driving force in type-nouns (even excluding the expletive type-nouns that have the same function) is shaming norm violators by way of contemptuous labeling, which would obviously function to maintain the cultural-moral rule system.

Other studies of type-nouns produced a similar picture. Structural analyses of personality-descriptive type-nouns were reported for the Dutch language (De Raad & Hoskens, 1990). Using 755 type-nouns as stimuli, descriptions of self and other were obtained from 200 pairs of persons in the Netherlands and Dutch-speaking Belgium. By far the largest (first) recurrent factor was labeled as Malignity (e.g., Monster, False-friend, Arch-villain, and Arch-hypocrite). Henss (1998) studied the structure of German type-nouns, selecting 192 type-nouns that were administered to 240 males and 240 females, each of whom was assigned to describe one prominent stimulus person selected from different fields of life. Factor analyses were conducted separately by gender of target. But both sets had one factor—easily the largest among women and nearly the largest among men—characterized by terms (in translation) like “pompous ass” and “pain in the neck.” Even though Henss emphasized representation of the Big Five in his selection of type-nouns, a non-Big-Five-like morality factor was still obtained.

But one need not restrict oneself to type-nouns in order to observe the centrality of moral content. Let us consider what appears to be historically the first very large-scale exploratory factor analysis of personality adjectives, which was accomplished in 1973 (in unpublished work) by Willem K. B. Hofstee. Hofstee analyzed the same set of 1,710 adjectives (with N = 204) used in later studies by Goldberg (1992) and Ashton, Lee, and Goldberg (2004). Operating in an environment not yet constrained by strong expectation of a Big Five structure or of even a structure in which the factors are all of relatively equal size, he extracted (and rotated by varimax) 21 factors. The first, and largest by far (accounting for almost 9% of the variance), was defined by the following adjectives having loadings of at least .60, in order starting with the highest loading: Ruthless, Cruel, Rude, Harsh, Brutal, Uncourteous, Coarse, Overviolent, Overfierce, Impolite, Heartless, Belligerent, Overharsh, Uncordial, Cold, Treacherous, Acid, Malicious, Pitiless, Cold-hearted, Hard-hearted, Slanderous, and Dictatorial. The highest loading adjectives on the opposite pole, all at least .50, were Giving, Gentle-hearted, and Humane. As is clearly evident in the content, this is another morality factor, here emphasizing maleficence (vs. non-maleficence). It is not an instance of a factor of the type labeled “Negative Valence” (e.g., Saucier, 2009) due to the substantial content on both poles of the dimension. Lest this dimension be dissociated too strongly from the earlier-cited English type-noun factor, it is worth noting that terms like Honest, Dishonest, and Deceitful also had their highest loading on this first factor, although these loadings were moderate in magnitude (.37 to .51 range).

| Jerk | … dull, fatuous, or stupid person |

| Weasel | … person regarded as sneaky or treacherous |

| Rat | … despicable or sneaky person, especially one who betrays or informs upon associates |

| Creep | … annoyingly unpleasant or repulsive person |

| Idiot | … foolish or stupid person |

| Scum | … one, such as a person or element of society, that is regarded as despicable or worthless |

| Moron | … person regarded as very stupid |

| Dummy | … person regarded as stupid; a silent or taciturn person |

| Nuisance | … one that is inconvenient, annoying, or vexatious; a bother |

| Phony | … one who is insincere or pretentious; an impostor, a hypocrite |

| Worm | … person regarded as pitiable or contemptible |

| Jackass | … foolish or stupid person; a blockhead |

| Dumbbell | … person regarded as stupid |

| Twit | … person regarded as foolishly annoying |

| Fake | … one that is not authentic or genuine; a sham |

| *Friend | … person who one knows, likes, and trusts … with whom one is aligned in a cause |

| Scoundrel | … a villain; a rogue |

| Pest | … annoying person or thing; a nuisance |

| Liar | … one that tells lies |

| Deceiver | [no distinct definition provided; but by implication, this is one who deceives] |

| Snake | … treacherous person |

| Traitor | … one who betrays one’s country, a cause, or a trust, especially one who commits treason |

| Crook | … one who makes a living by dishonest methods |

| Incompetent | … devoid of those qualities requisite for effective conduct or action |

| Hypocrite | … person given to hypocrisy [falseness] |

Note. Source of definitions is American Heritage Dictionary (1991). *This term has a high negative (rather than positive) loading, is antonymous to other terms. |

|

Saucier, Thalmayer, Payne, et al. (2014) examined lexical-study datasets from a very diverse set of languages, from Africa, Asia, and Europe. They found that two-factor structures universally included a factor of “Social Self-Regulation” (S) whose most recurrent descriptors are Honest, Kind, Generous, Gentle, Good, Obedient, and Respectful. The S factor is usually the larger of the “Big Two,” and when only one factor is allowed, its content is primarily S content. It draws together Honesty and Agreeableness content, as well as the most moralized aspects of Conscientiousness (i.e., diligence and responsibility). Another study (Saucier, Thalmayer, & Bel-Bahar, 2014) found that morality and social self-regulation content was ubiquitous across languages at a level markedly higher than that for Big Five factors. Indeed, such content displayed a level of ubiquity similar to that for Wierzbicka’s (1996) semantic primitives (good-bad, big-small) and Osgood’s (1962) semantic differential dimensions.

So is the largest factor in the personality domain—as defined in the most conventional way, by adjectives from the natural language—actually morality? What emerges as the largest factor depends, of course, on variable selection. The importance of variable selection accounts for why moral content was relatively absent from early models of personality, like those of Eysenck and Cattell, not to mention the original NEO-PI inventory of Costa and McCrae (1980), which was originally based on analyses of Cattell scales. The great structural innovation of the 1980s was the grafting of previously omitted content of an at least partially moral nature onto previous models, a fertile communion which created current conceptions of the Big Five.

The field of personality psychology, at its inception (e.g., in the influential early work of Gordon W. Allport), peripheralized ethical/moral attributes. This slighting of the ethical likely stems from historical conjunctions associated with the development of moral philosophy. The time period in which personality psychology arose was one in which, in philosophy, emotivist conceptions of morality were strongly influential. For example, Ayer (1936) argued that moral language simply expresses feelings toward various classes of actions, and does not refer to anything substantive. Stevenson (1944) suggested that such language functions additionally to manipulate others’ emotions and attitudes; as with Ayer, moral language was thought to not have a descriptive function (MacIntyre, 1966).

In the early years of personality psychology, similar assumptions were adopted by key figures; they were consistent with the dominant behaviorist paradigm of the day. For example, it was assumed that moral characterizations say more about the perceiver than about the perceived. Allport set aside morally evaluative terms, as he did terms describing feelings and emotions, as not of central relevance for personality psychology: such terms should be avoided by psychologists in this field, since they could not refer to “neuropsychic dispositions.” Given acceptance by other leaders in the field, the downstream result was a field whose prime variables through the middle of the 20th century were non-moral variables: extraversion and neuroticism. Consonant with these predilections against whatever hinted at a moral characterization, in 1945 the American journal Character and Personality changed its name to the still-retained moniker of Journal of Personality. Although “character” had multiple meanings at the time, the shift was consonant with analogous shifts in the broader culture, what Susman (1984), based on studies of self-help books across time, has labeled a shift from a culture of character (emphasizing duty, reputation, honor, morals, and self-discipline) to a culture of personality (emphasizing that one be magnetic, bold, and entertaining).

Gradually, by taking account of ever wider evidence, the field of personality steadily corrected this imbalance. A key development was a line of investigations that followed Allport’s initial foray in that direction. Tupes and Christal, Digman, Norman, and Goldberg identified in American data a Five-Factor (Big Five) Model that included dimensions of Agreeableness and Conscientiousness. These dimensions included elements of morality, such as potentially ethical virtues like kindness, unselfishness, and dependability, and were incorporated in what became a popular five-factor inventory (Costa & McCrae, 1992). Eventually, projects were initiated in various languages that found increasing evidence for a sixth dimension related to honesty (Ashton et al., 2004; Saucier, 2009), even more directly related to the ethical virtues. Indeed, Lee and Ashton (2012) suggest that Honesty is the single most important dimension of personality.

The belated empirical discoveries of a morality-related personality dimension support a position frequently found among philosophers, that certain aspects of normative ethics are quite generalizable across human contexts. And, extending the process that led earlier to Big Five and then Big Six models, this position arguably helps complete the correction for an essentially emotivist bias against moral/ethical virtues that has been implicit since the early days of the personality field. Nonetheless, history has consequences, and one consequence is that dimensions like extraversion and neuroticism are typically considered the most prototypical of the personality domain, although studies of the natural language (especially if one deigns not to exclude the type-nouns) indicate centrality for the moral characteristics.

What is implied—and not implied—by the proposition “Morality is central to the domain of character and personality”? It is not intended that moral content constitutes a majority of content in this domain. Centrality does not mean that a majority of either personality attributes or personality dimensions are moral, as there are many extremely useful sources of variance away from the center. For example, one might bring to mind extraversion, emotional stability, creativity, and so on. There are many personality dimensions, but based simply on their number and the strength of their intercorrelation—which reveals strong consensual underlying constructs in the human minds and perceptions that are reflected in the ratings—morality comes first. Attempts to reduce the domain of character and personality entirely to neurophysiological predispositions are prone to miss the impact of culture. Although variation in moral character clearly partakes of genetic influences—witness the genetic underpinnings of psychopathy (Skeem, Polaschek, Patrick, & Lilienfeld, 2011)—this variation is driven by the sociocultural environment—including moral norms—in which the human being must necessarily operate.

To this point, principles indicate that humans are cultural animals whose cultures have moral norms at their center and whose language of personality characteristically has considerations of moral character at its center. Given the high social desirability of moral character, why would not everyone possess it? What dynamic drives this variation?

4. Variation in moral character, broadly conceived, arises from competing pressures of norms versus what broadly constitutes self-interest. Self-interest here is taken to be a summation of hedonic motives (e.g., the desire to minimize pain and maximize pleasure) and striving to enhance power for self or for one’s immediate group. Norms on the other hand manifest as externally recognized laws or as an internalized sense of obligation to which one feels a sense of commitment or merely a recognition of what ought to be said or done.

This conception of character dynamics is congruent with approaches taken by Wilson (2004), a moral philosopher, and Bailey (2001), a cultural anthropologist. Wilson notes that as humans we frequently constrain ourselves “by internalized canons of appropriateness, decency, taste, and civility that forbid us certain actions that we could easily perform …” (2004, p. 5). Moral rules, in particular, are “restrictive and prohibitory rules whose social function is to counteract the short- or long-term advantage possessed by a naturally or situationally favored subject” (2004, p. 9). These rules “are concerned with the regulation of actions that can be broadly described as self-interested … limiting the physical and psychological damage individuals can do to one another in pursuit of their own interests or the interests of their party, class, nation, or tribe” (2004, p. 11). She characterizes them as, paradoxically, rules for not getting ahead, which presuppose a willingness “to accept a reduction of advantage to benefit another …” (p. xii). Bailey (2001) states a similar notion in simpler terms, of a “tension between dutiful action and self-interest” (p. 1). According to Bailey (2001, p. 127), “in reality behavior is not entirely directed by conscience and a sense of duty; it is also the product of self-interest, ambition, and fear. People do not always do what they are normatively supposed to do.” This reality is driven by the contrast between the rules of a normative code and those from a strategic code (which is more concerned with effectiveness than morality). Bailey points out that people (especially in politics) often benefit from circumventing the moral/normative code, even if they all the while maintain a façade of normative acceptability. An implication is that people will want to achieve power and self-interest but will not necessarily say so, given the expectations stemming from the normative code. In theory, this is the origin of the concern with deception that is so evident at the center of the structure in type-nouns.

At first glance, it might be surprising that there is individual-level variation in sociomoral self-regulation at all, given the pressure to observe consensual evaluative standards. One might expect such pressure to produce considerable uniformity. But there are trade-offs involved. Let us assume that all individuals have internalized the same moral standards, and to the same degree. Just how much should one let these moral standards inconvenience one’s pursuit of pleasure, possessions, and a position of power? There is reason (for many) to limit the inconvenience these standards introduce.

However, the foregoing assumption—that all individuals have internalized the same moral standards and to the same degree—is too strong. Instructive here is a distributive model of culture (e.g., T. Schwartz, 1978). According to this model, culture is a complex pool of knowledge distributed variably within individual mindsets, with some elements shared more widely, others less. The degree and content of sharedness depends partly on age cohorts or role specialization; some individuals are better representatives than others of the central tendency in their cultural group. Thus one additional source of variation in moral character is the degree of knowledge of cultural norms, and of identifying with or internalizing those one has come to know. A second additional source of variation is subcultural variation (e.g., between generations, classes, or ethnic subdivisions) in what the moral norms are understood to be. A third, holding knowledge and subculture constant, would be values: competing values are involved, as referenced in a major dimension of self-enhancement versus self-transcendence (S. H. Schwartz, 1992), one promoting self-interest and the other obligations toward others.

The notion that variation in moral character is driven by conflicts between duty and self-interest has a familiar, common-sense feel. One might cite as evidence the content of scales to measure the personality dimension of Honesty. A Big Six measure (Thalmayer & Saucier, 2014) employs items like “Use others for my own ends” and “Steal things” that express a tendency to pursue self-interest in contravention of moral rules. A HEXACO measure (Lee & Ashton, 2004) has some items that suggest a self-interested gain (e.g., using counterfeit money, getting a million dollars, and getting a raise or promotion) when the norm-enforcement cost in terms of potential sanctions (e.g., getting caught, not getting away with it, having a lie or pretense called out) is low, thus getting at the respondent’s degree of internalization of moral norms. One might also effectively tap variation by counterposing high-cost dutifulness with an understandable pursuit of self-interest, as in the anti-Machiavellian notion that you should never take advantage of others, even if others are taking advantage of you.

To this point, principles indicate that humans are cultural animals whose cultures have moral norms at their center and whose language of personality characteristically has considerations of moral character at its center, the variation in which is driven by the tension between self-interest and dutiful action. This suggests a fairly universal template that might apply in any cultural context. We can now extend this ubiquitous template a bit farther with one additional principle.

5. A certain skeletal core of moral rules is conserved across cultures. There is evidence indicating that virtually any language will have a moral vocabulary, with notions like good and bad, right and wrong, disobedient, wicked, and so on (Saucier, Thalmayer, & Bel-Bahar, 2014). But such global attributes specify little about what actions are good or bad. Gert (2004), a moral philosopher, proposes a basic core of moral rules that any rational person (presumably in any culture) would assent to. These include do not kill, cause pain, disable, deprive of freedom, deprive of pleasure, deceive, or cheat; obey the law, keep your promises, and do your duty. They constitute, potentially, a set of universally recognizable human rights. All of Gert’s rules tend to focus on avoidance of harm, and along similar lines Nichols (2004) has suggested that harm-related norms are universal, because they have an affective resonance that is advantageous from the standpoint of cultural evolution. Bok (1995) is more overt about what moral duties may be pervasive across cultures, providing “the rudiments of a shared minimalist ethics” (p. 57) that might apply across human communities and involving duties of mutual support and loyalty, constraints on specific kinds of violence and dishonesty, and justice with respect to conflicts between values. Vauclair and Fischer (2011), relying on empirical data, suggest that there are smaller between-population differences in illegal-dishonest moral violations than in those of a personal-sexual nature, with the implication that the former are more conserved across cultures. Miller’s (2007) review of the cultural psychology of moral development identifies not only numerous areas of cross-cultural variation but also a few commonalities: justice concerns appear to be universal, and theft and some forms of assault may be ubiquitously recognized as justice violations. Shweder (1991, p. 190) suggests that, for example, American and Oriya (India) people are different in many ways, even in some aspects of their moral ethic, but in both cultures “it is wrong to engage in arbitrary assault, break promises, destroy property, commit incest.”

We should be clear about what type of morality these moral rules represent. In terms from Kohlberg (1971), this is conventional morality, a rule-following ethic based on identifying with a society’s moral code, an ethic of the sort found readily in adults around the world. It is not a postconventional morality that posits free-floating abstract principles of justice or individual rights (a sort identifiable mainly in Westerners, and even then just a minority).

And the degree of universality of moral rules should not be overstated. D’Andrade (2008) has observed that there is surprisingly little variation in values between cultures, but there appears to be far more variation in “what counts as what.” Applied here, a crucial question is “what counts as an unjustifiable harm?” For example, whether selling marijuana to an acquaintance or having sex outside of marriage counts as an inflicted harm depends on the culture, the jurisdiction, even the person.

Another obvious line of variation both within and between cultures would stem from moral inclusion. Are the ubiquitous refrain-from-harming rules applied to all humans, or only to members of a narrower group (e.g., family, tribe, and nation)?

And yet a third source of variation would arise from rules, varying by religious community or political persuasion, that involve harm less directly than other considerations like obedience to authority, loyalty to an in-group, proper conduct of ritual, or personal purity or chastity or abstinence from vices. There are indications (Saucier et al., 2015) that content reflecting such in-group assortative “binding” forms of morality show larger cross-cultural differences than is found for item content referencing the need to reduce harm and injustice.

Although humans are no doubt biologically prepared from evolutionary selection to learn such rules and to sanction deviations from them, moral rules can be generally presumed to be culturally learned. Knowledge of such rules—and fidelity to them in behavioral practice against the strong undertow of self-interest—is captured by constructs like Honesty and Social Self-Regulation. Arguably, these are tethered to the largest most central dimension in the personality domain—that of moral character. Although there are certainly important variations between communities in the nature of such moral rules, there do appear to be some common aspects. So we can posit that all cultures possess moral rules and differentiate people based on the strength of their tendency to dutiful action inspired by such rules. But not only that: also that certain rules about avoiding harm and unfairness to others have wide circulation in human societies. So the largest factor in personality (character) is profoundly cultural, but is not necessarily a source of cultural differences; it draws on dynamics that appear to have good commonality across cultures. Moral attributes of character, and the dimension of sociomoral self-regulation of which they are the center, are an important intersection of culture and personality/character. They are the locus at which cultural socialization most strongly touches the domain of personality.

Moral rules do not appear, however, to be the best place to look for cultural differences. And neither do personality characteristics appear to be a promising place to look.

6. Behavioral attributes, as represented in most personality scales, are not a prime locus for cross-cultural differences. This is an empirically based observation, though with good theoretical or methodological rationales for why it should be the case. And a few caveats are in order with regard to what constitutes a “personality scale.” But let us begin with the empirical evidence.

In a global Survey of World Views, Saucier et al. (2015) administered a diverse set of 281 items of a psychological nature to 8,883 participants (mostly college students) from 33 different countries around the world; the population of these 33 countries added up to some 67% of the total world population in 2012 (the year the questionnaire was administered). A prime aim was to investigate which kinds of variables (or item content) might have the most or least cross-cultural variation. In line with this goal, the key analysis was the computation for each item of the percentage of variance accounted for by participants’ country of origin (indexed by intraclass correlation or eta-squared coefficients, which yielded similar results). The emphasis on item-level results, treating each item as a variable on its own, is consistent with the approach in the previously published study (Saucier et al., 2015).

At this point, it suffices to mention that the 281 items included 40 items that derived ultimately from the International Personality Item Pool (Goldberg et al., 2006), most of which were constituents of the 36QB6 measure of the Big Six structure (Thalmayer & Saucier, 2014). Approximately 1/7 of the questionnaire’s items were personality items, but not a single one of these personality items generated an eta-squared greater than .15; in fact, the eta-square values for these 40 items ranged from .026 to .148 (mean .074), suggesting only small to medium effects of culture. Averaging the eta-square values by Big Six domain—Agreeableness .047, Resiliency .061, Honesty/Propriety .062, Extraversion .075, Conscientiousness .088, Originality/Intellect .109—suggests that, among personality dimensions, those related to morality are in the low range and those related to “openness” are in the high range for cultural differences. But none of these differences are of large effect size.

There are not many analogues to this study, in which personality items were administered in a single study across a broad range of countries, and then item-level indices of culture effects were calculated. It would be useful to apply the same approach to other archival data where available.

There are several reasons to expect modest-size cultural differences in personality-descriptive items. The first is reference-group effects (Heine, Lehman, Peng, & Greenholtz, 2002), which arise because individuals implicitly rate themselves (or others) against a normative reference group, and these reference groups may be profoundly different from one cultural context to another. It may be that we will only see personality differences between cultural groups clearly if we base them either on behavioral frequency counts or on ratings by objective third-party judges (who in common know or at least observe participants in all the cultural contexts).

A second reason to expect only modest differences is that personality variation may be highly subject to a balancing form of frequency-dependent selection, in which a trait becomes less differentially adaptive as it becomes more common. This is most evidently the case for amoral tendencies. A small proportion of cheaters (wolves) can have a field day with a large population of cooperators (lambs), but this does not mean that wolves will ultimately outnumber lambs. Society may benefit from aggregate behavioral versatility in its membership. A herd would do well to have a cadre of opportunity seekers who will find greener pastures, as well as a balancing cadre of threat avoiders who will monitor the environment for predators. On this view, risk takers and neurotics can make complementary contributions to group success.

A third possible reason is that what is most conventionally considered personality may specifically exclude those kinds of individual differences that do in fact vary most substantially across cultures. This possibility is best addressed after identifying the variables with the largest cultural differences, and then exploring how they are or might be indexed on personality measures.

7. Among psychological variables, the largest cross-cultural differences pertain to what is religious or “quasi-religious.” This principle goes against the gradually adopted canon that the single most important contrast in cross-cultural psychology is between individualism and collectivism. However, the early studies in that field tended to be limited by inadequate data. One tends to find only a modest range of variables, and a representation of countries that do not fairly represent the world population: Western countries were over-represented or more densely sampled, especially in comparison to Africa and South Asia. This pattern derived from the understandable tendency to concentrate on participants who are “easy to come by,” that is, mainly from those countries with the largest concentrations of psychologists. (The same problem limits inferences in the field of personality.)

The Survey of World Views project (Saucier et al., 2015), by design, included a very large range of item content: several dozen variables that might be compared with respect to degrees of similarity and difference across samples. And it featured a stronger proportional representation of the “global south” (Africa, south/southeast Asia, Latin America) than has been typical in these studies, so as to represent a majority of the world’s population by its selection of countries. Reflecting the assumption that culture is defined especially by shared ways of thinking, items predominantly referred to beliefs, values, and norms.

Coefficients (eta-square and ICC) were generated for 281 items, using the maximum sample sizes available for each item. Data from 30 countries were utilized: removal of three Western countries (Australia, Ireland, and the Netherlands) that had unusually small samples lessened the tendency toward an over-representation of European-origin populations (although results were demonstrably very similar if these countries were nonetheless included).

Table 10.2 shows the items with the largest differences between countries. Among the 42 items with the largest ICC (or eta-square, which were very similar) values, the largest differences were on contents involving devotion to religion, ethnonationalism, hierarchical family values, and aspects of family-oriented collectivism. These were large effects: country-of-origin accounted for 20–40% of the variance in the item—well above the range cited for all the personality items mentioned earlier.

Although unexpected in some ways, the results were not entirely without precedent. Large cross-cultural differences in beliefs connected to religion (or the metaphysical)—especially on practices and behaviors that reflect the everyday impact of religion on persons—has been found previously (see, e.g., Fischer & Schwartz, 2011). There has been less previous cross-cultural work on ethnonationalist sentiments, but they partake of a quasi-religious character. Anthony D. Smith characterized ethnonationalism as a “political religion” or “surrogate religion” (Smith, 2001, p. 35), with appeal and endurance based on “deep-rooted, enduring religious beliefs and sentiments, and a powerful sense of the sacred” requiring “absolute loyalty” (Smith, 2003, p. vii). As Smith describes, ethnonationalist sentiments often cast one’s ancestral group as a chosen people with a special destiny, with a kind of collective immortality achieved via heroic devotion to the nation.

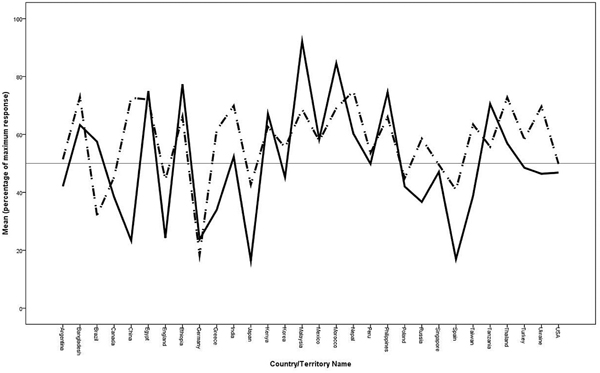

Figure 10.1 shows the country means (for the 30 prime countries) for two collections of items that show large cross-cultural differences and were included in the Survey of World Views dataset: the three intrinsic religiosity items from Koenig, Patterson, and Meador (1997) and the four ethnonationalism items from Saucier and Bou Malham (2015). This figure should be interpreted with caution, inasmuch as measurement invariance is not documented for these collections of items. However, the figure gives preliminary indications for how variables map onto countries.

The current proposition (principle 7) simply states what appears to be an empirical fact: that, in the contemporary world at least, variables of a religious (or quasi-religious) nature show the largest cross-cultural differences. This fact has potentially important implications. It argues against insularity, highlighting the overlap of cultural psychology most prominently with the psychology of religion, and with political psychology. And it might spur theoretical development, by virtue of the puzzle it generates. What theory of culture can best make sense of the high profile of religion and ethnonationalism in how populations differ?

| η2 | η2ips | ICC | ICCips | Item in Full |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| .39 | .31 | .37 | .29 | How often do you spend time in private religious activities, such as prayer, meditation, or study of religious scriptures? |

| .39 | .27 | .38 | .27 | How often do you attend church, mosque, temple, or other religious meetings? |

| .36 | .29 | .35 | .27 | I try hard to carry my religion over into all other dealings in life.* |

| .33 | .28 | .32 | .27 | Religion should play the most important role in civil affairs. |

| .33 | .26 | .32 | .25 | My religious beliefs are what really lie behind my whole approach to life.* |

| .31 | .26 | .30 | .25 | In this society, children generally live at home with their parents until they get married. |

| .31 | .25 | .31 | .24 | At a critical moment, a divine power will step in to help our people. |

| .30 | .23 | .31 | .24 | In this society, a mother sleeps with her child until well past the child’s second birthday. |

| .30 | .25 | .28 | .23 | I adhere to an organized religion. |

| .28 | .21 | .28 | .21 | We need tough leaders who can silence the troublemakers and restore our traditional values. |

| .27 | .20 | .26 | .19 | Men and women each have different roles to play in society. |

| .26 | .20 | .24 | .18 | If you are protecting what is sacred and holy, anything you do is moral and justifiable. |

| .26 | .18 | .28 | .17 | In this society, aging parents generally live at home with their children. |

| .26 | .19 | .24 | .17 | [What’s right vs. wrong can be decided based on] Whether or not someone’s action showed love for his or her country. |

| .26 | .20 | .23 | .19 | I honor the glorious heroes among my people who sacrificed themselves for our destiny and our heritage.** |

| .25 | .19 | .23 | .17 | In my life, I experience the presence of the Divine.* |

| .24 | .20 | .25 | .21 | Respect for authority is something all children need to learn. |

| .23 | .16 | .23 | .16 | In this society, individuals occasionally become possessed by a spirit, who temporarily takes possession of that individual’s body. |

| .23 | .19 | .22 | .18 | My first loyalty is to the heritage of my ancestors, their language and their religion.** |

| .23 | .17 | .23 | .17 | I can always trust the government to do what is right. |

| .23 | .18 | .23 | .18 | My honor is worth defending, even aggressively. |

| .23 | .16 | .22 | .15 | In this society, people fear that if they break social rules then others will use sorcery or witchcraft against them. |

| .22 | .17 | .21 | .16 | I believe in predestination—that all things have been divinely determined beforehand. |

| .22 | .15 | .22 | .15 | The mother should accept the decisions of the father. |

| .22 | .17 | .21 | .17 | In this society, people believe that the spirits of dead ancestors are active and can affect events in everyday life. |

| .22 | .16 | .22 | .16 | The father should be the head of the family. |

| .22 | .18 | .23 | .19 | The homeland of my people is sacred because of its monuments to our ancestors and heroes.** |

| .21 | .14 | .19 | .13 | I am proud of my country’s history. |

| .21 | .17 | .21 | .17 | I believe in the superiority of my own ethnic group. |

| .21 | .16 | .22 | .16 | In this society, boys are encouraged more than girls to attain a higher education. |

| .20 | .18 | .20 | .18 | In this society, teen-aged students are encouraged to strive for continuously improved performance. |

| .20 | .16 | .20 | .16 | My ancestors once lived in a golden age with glorious and beautiful achievements.** |

| .20 | .15 | .20 | .15 | Foreigners have stolen land from our people and they are now trying to steal more. |

| .20 | .14 | .20 | .14 | The father should handle the money in the house. |

| .20 | .15 | .21 | .16 | Going to war can sometimes be sacred and righteous. |

| .19 | .12 | .19 | .12 | Religious faith contributes to good mental health. |

| .19 | .15 | .21 | .16 | It is always smart to be completely truthful. |

| .19 | .24 | .22 | .28 | In this society, alcohol is consumed frequently and occasionally in great quantities. |

| .19 | .13 | .20 | .14 | Parents and children must stay together as much as possible. |

| .18 | .17 | .17 | .16 | What is good can be judged only by the gratification of the senses. |

| .18 | .14 | .18 | .13 | [What’s right vs. wrong can be decided based on] Whether or not someone was good at math. |

| .18 | .22 | .23 | .23 | My own race is not superior to any other race. |

Note. N ranges from 7,268 to 7,871 depending on the item. η2—eta-squared; ICC—intraclass correlation (ICC[1]); ips—in ipsatized data; η2 and ICC indicate the proportion of between-individual variance in the item accounted for by between-country differences. *Intrinsic Religiosity item referenced in Figure 10.1. **Ethnonationalism items referenced in Figure 10.1. See Saucier et al. (2015) for indicators as to the source for other items. |

||||

Before going on to sketch the beginnings of a theoretical framework for why it arises, we can use this empirical fact to introduce a caveat to the preceding proposition (principle 6) that personality items—behavioral attributes—are not a prime locus for cultural differences. Allport (1937) stated that “the more generalized an attitude”—that is, the wider variety of targets it is addressed to—“the more does it resemble a trait” (p. 294). Being religious, or ethnonationalistic, might well be considered a trait. The former at least demonstrates retest stability coefficients at least as high as those for conventional personality traits (Saucier, 2008). And indeed, some multiscale personality inventories include related constructs. The Temperament and Character Inventory (Cloninger, Przybeck, Svrakic, & Wetzel, 1994) includes a multifaceted scale for Self-Transcendence; Tellegen’s (in press) Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire has a scale for Traditionalism; and the Omnibus Personality Inventory (Heist & Yonge, 1969) one for Religious Orientation. The Openness to Change scale from the 16PF (Conn & Rieke, 1994) may fall into the same class. These inventories have not been the target of wide-scale cross-cultural comparisons, but if they were, one can predict (based on the current principle 7) that these will be the single scales within their respective platform that shows the largest cross-cultural differences.

That religious—and quasi-religious—variables show the largest cross-cultural difference is an empirical fact that demands some explanation. A simplistic explanation would be that some societies are religious and others are not. Such a proposal would be undercut by the persistence of religious persons in largely secular societies and of nonreligious persons in the apparently religious societies. This simplistic proposal would moreover be guilty of stereotyping. Instead, here is offered a more subtle general principle.

8. Any society has two realms of culture: sacred (meaning oriented) and secular (instrumentally oriented). Let us begin by supposing that a neutrally framed contrast of societal types underlies the psychological variables having the largest between-country effect sizes. As Figure 10.1 indicates, eastern hemisphere countries from the global South are most likely to be on one side, whereas countries in Western Europe are most prone to be on the other side.

This contrast of societal types can be framed in terms of theory imported from anthropology. Some cultural anthropologists have highlighted the material side of culture (e.g., Harris, 1979) and others the sacred side (e.g., Rappaport, 1999). A way of bridging the two viewpoints comes from La Barre (1970), who identified two realms of culture: an outer-adaptive or secular realm oriented to known material realities and an inner-adaptive or sacred realm oriented to accessing shared meaning in the face of potential uncertainty and anxiety. Both realms are presumably found within any culture. In terms from Bailey (2001), the material side of culture is oriented especially to strategic rules (how to be effective). The sacred side orients more to unquestioned worldview assumptions that undergird a particular society, what Rappaport (1999) termed “cosmological axioms” and “ultimate sacred postulates.”

It was noted earlier in the chapter that all cultures possess moral rules and differentiate people based on the strength of their tendency to dutiful action (which regulates pursuit of self-interest) based on these rules. It may appear to some that such moral rules inhere in the sacred side of culture, but this would be most true in a very religious culture. Secular moralities are also possible, and indeed the law codes of more secular societies contain strands of such moralities, with moral desiderata less often found in religion-based moral systems, such as tolerance, freedom from discrimination, and environmental sustainability. The sacred side of culture is most of all focused on systems that provide meaning; in the absence of religion, a society does not totally lack normative standards. Such norms could arise from legislatures or local councils, but norms arise more informally whenever people communicate regularly with one another (Harton & Bourgeois, 2004).

9. Societies differ (at any point in time) in the relative priority/predominance of the sacred and secular realms of culture. One may go further than simply postulating there are two realms of culture. It appears that societies differ, at any point in time, in the comparative vigor of these two realms of culture, and in the degree to which one realm is given privilege over the other. The realm that is privileged comes to regulate the other. Table 10.3 introduces a novel inductive framework contrasting societies oriented to an enduring normative order versus societies oriented to an evolving normative order. These two types merely define extremes of a continuum; as Figure 10.1 might imply, many actual societies negotiate intermediary places on the continuum and can move in one direction or the other over time. Such a distinction is captured to a moderate degree by the S. H. Schwartz (1992) values dimension of conservation versus openness to change, but as conventionally measured, this dimension shows considerably less between-country variation than do variables of religiosity and ethnonationalism (Saucier et al., 2015).

Enduring-order societies emphasize a core tradition held sacred that provides a shared meaning system. The meaning system is transmitted vertically from older to younger generations, a process that might inherently play up ethnic ancestry and time-honored religious traditions. Thus, this corresponds to a “postfigurative” culture as described by Margaret Mead (1970). The ethnographic record indicates that postfigurative enduring-order societies are historically quite the norm (Fox, 2011) and may be a baseline state to which societies tend easily to revert.

In contrast, evolving-order societies emphasize material culture and technological innovation, which facilitates change and creates ongoing transition rather than tradition. In these societies, one sees a greater degree of horizontal peer-network transmission of cultural information; thus, in Mead’s terminology, they are “cofigurative.” The emphasis on innovative technological expertise means a less central role for elders. Being less committed to tradition, these societies can afford a greater receptivity to environmental inputs that might generate “evoked culture.” The vertical transmission of tradition takes a less central, more peripheral position in society. In such a society, tribalistic in-group favoritism is regulated in a kind of intertribalism; group loyalties are, at least in part, channeled to a more superordinate level.

| Enduring-Order Societies | Evolving-Order Societies |

|---|---|

| Value (seek, preserve) an enduring normative order | Value (or at least tolerate) an evolving normative order |

| Default—historically more common—desire for which stimulated/reinforced by various conditions of stress, its variant forms originally functioning as stress-minimizers | A variant overriding the default—more rare—arising primarily in prosperous low-stress conditions; under threat or stress, population tends to return to default (see left) |

| Oriented to maintain/protect shared meaning in a worldview/value system, satisfying existential needs for certainty. Ensures: Constant tradition | Oriented to strategic success in instrumental ends, material security, use of technological innovation. Material culture. Accepts: Constant transition |

| Oriented foremost to a sacred (held ancient or timeless) realm (La Barre, 1970) | Oriented more strongly to realm of secular (La Barre, 1970) |

| Focuses heavily on transmitted culture, sometimes zealous protection from outside influences, new “data” often ignored; in that sense culture is more “theory based” | Focus shifts to evoked culture, cosmopolitan adaptation to outside influences, what current “data” indicates; in that sense culture is more “data based” |

| More of vertical (elder to younger) cultural transmission (i.e., postfigurative; Mead, 1970) | More of horizontal peer-network cultural transmission (i.e., cofigurative; Mead, 1970) |

| Cooperation preferentially channeled via forms of “tribalism,” via ties of blood and common ancestry, or religions that can bind people by common belief, authority into wider in-group; these in-groups regulate individual behavior; particularism is unregulated, given free play | Cooperation preferentially channeled via forms of “intertribalism,” via civic superordinate ties transcending ethnic and religious identities; ties of ethnicity and sect/religion more regulated (given less free play), while pursuit of personal strategic ends up more unregulated |

A given population is not strictly fixed to one point or extreme on this fundamental cultural continuum. A society at the enduring-order extreme is not exclusively a sacred culture, just as a society at the evolving-order extreme is not exclusively a secular culture. Since any society already includes both sacred and secular cultural realms, changes in which realm has the lead role (and so regulates the other) could be accomplished even without importation of new cultural contents. Although drastic shifts seem not to be frequent, a society can within a few generations slide dramatically in one direction or the other. Religious awakenings or increases in ethnonationalist fervor may take the society one way, or declines in religious belief or nationalistic sources of identity may take it the other way.

In American political discourse, these two sides of culture have sometimes been identified with the distinction between church and state. These two sides (as would characterize an evolving-order society) are to keep some distance from each other. Although it does appear that the state regulates the church more than the other way around, some socially conservative political factions argue that this relation should be reversed.

It should be stressed that the framework laid out in Table 10.3 was stimulated by patterns in data from the 2012 Survey of World Views. It cannot be decisively tested in the present data and is in need of an adequate measurement operationalization. Items in Table 10.2 may contribute to this, particularly those that reference the relative priority given to sacred-culture (enduring normative order) and secular/material-culture (evolving order) components, where they might intersect, overlap, or come into conflict. Only one questionnaire item in Table 10.2—“Religion should play the most important role in civil affairs”—fully embodies this key ingredient.

So far, the sequence of principles has accounted for a surface-level empirical finding—of large-size cross-cultural differences in religious and quasi-religious content—by identifying its deeper roots in a cultural continuum: enduring-order and evolving-order societies at the extremes reflecting differing relative predominance given to sacred and secular/material realms of culture. But why do these two distinct realms of culture arise?

10. Humans and their societies respond to an existentially difficult situation with a combination of instrumental adaptations and a projected cultural worldview attributing sacredness and providing meaning. The principle here is that there are differing directions of response to the fundamental existential situation of the human in society. And these generate the two realms of culture discussed above.

Let us assume, to borrow some terms from La Barre (1970, p. 349), that heartless winds shape the universe. Even if this premise turns out to not be ultimately true, there is an existential reality by which it certainly can look that way, and humans and their societies respond to this existential reality (how it looks). It is a discouraging if not terrifying situation. But there are ways to deal with this predicament. One can attempt to understand and make use of the winds, perhaps in ever-evolving ways; thereby one develops the capacity to be instrumental and coercive with respect to nature and bends it to human purposes. Or alternatively, one can construe them to be not so heartless after all, reinstating meaning by imposing or projecting a more comfortable veneer of reality on the universe; this would be most effectively done in a way that will endure, rather than needing to be reconstituted with every generation, Naturally, most humans do not like to live in a world in which they fight to survive and reproduce with no sense of an appealing or inspiring meaning or redeeming value behind it all. As La Barre (1970) points out, an extremely common if not universal theme in the projection of meaning onto the universe is to postulate unseen forces (spirits or gods) that have human- or animal-like qualities and with whom one can interact in a relatively personal way, which can include commanding these forces (as in magic) or beseeching them for assistance (as in religion).

Bailey (2001) observes that it “is part of human nature to look for and need to find meaning in what happens” (p. 126). He goes on to a further generalization: “Order is anchored in religion, faith, in a normative framework regarded as an eternal verity” (p. 127). Although normative frameworks can also be anchored on the side of a secular, evolving order (as in the ideal of communal rationalism that informs a legislature), Bailey here taps into how religious psychology satisfies what psychologists call the need for meaning. This need has been given short shrift in motivational classifications, but recent cross-cultural evidence (Church et al., 2013) suggests that it is at least as important as the three needs postulated in the well-known Self-Determination Theory of motivation (Ryan & Deci, 2000).

So humans desire not only to survive and be effective with the environment into which they are existentially thrown but also to have a sense of meaning, order, and coherence within their lives and their society. What principles should inform our handling of the two realms of culture and the two aspects of human nature that they reveal?

11. Sacred culture is a double-edged sword—and the same may be true for secular, material culture. There is some evidence that sacred culture, as represented most prominently in institutional/traditional religion, can be an important satisfier of the need for meaning (e.g., Emmons, 2005). The religious, as well as the conservatives who put a premium on traditional religion, are happier (Hackney & Sanders, 2003; Schlenker, Chambers, & Le, 2012; but see Wojcik, Hovasapian, Graham, Motyl, & Ditto, 2015), though perhaps mainly so to the degree that their society is strongly religious (Diener, Tay, & Myers, 2011). Religion, as well as shared ethnic identity, is a source of social capital of the “bonding” though not the “bridging” type (Putnam, 2000). It may be protective against some social problems, such as loneliness (Rote, Hill, & Ellison, 2013), acceptance of suicide as an option (Stack & Kposowa, 2011), and substance abuse (Moscati & Mezuk, 2014). Based on the explicit content of religious messages, we might expect religion to be a source of compassion, generosity, and hope, and both religion and identification with a rich ethnic heritage might promote courage and heroism. Ethnonationalist sentiments have been the inspiration for effective programs of nation-building over the last two centuries (e.g., in Latin America and Eastern Europe).

But this sword cuts both ways. On the other side, manifestations of sacred culture have been associated with violence on sometimes quite a large scale. These arise in the course of protecting a particular meaning system against threats, or otherwise asserting it against the nonbelievers. Historical examples are so abundant that they suffice to make the point. Recent examples include ad-Dawlah al-Islāmiyah fī ’l-ʿIrāq wa-sh-Shām (Daesh; ISIS), Boko Haram, the Taliban, and al-Qaeda. Nazi Germany and imperial Japan (through World War II) can be read as regimes riding high on crests of ethnonationalist sentiment, and sentiments of this type also drove the Rwanda genocide. Less intuitive examples from the last century are nontheistic political cultures of Leninism, Maoism, and the Khmer Rouge, which arguably created a sacred out of an ideological system and defended it in a quasi-religious way. Beyond the last century, of course, one could cite the Wars of Religion in Europe, the Inquisition, and the Crusades as prominent examples of sacred culture gone violent. Characteristic of such a development is the compartmentalization of ubiquitous ethical constraints against harming and injuring, so as to allow for extreme harm and injury to an out-group. In the terms of Moral Foundations Theory (Haidt & Joseph, 2008), this is binding-foundation morality without the constraints imposed by individualizing-foundation morality.

The evidence on both sides is less clear at this point, but a promising hypothesis would be that secular, material culture is also a double-edged sword. On the good side, it yields technological innovation, as well as tolerance, multiculturalism, and attention to universal human rights. On the bad side, this realm of culture left on its own seems to spin off materialism and a superficial consumer culture that is detrimental to well-being (e.g., Dittmar, Bond, Hurst, & Kasser, 2014), and anomic alienation that might contribute to substance abuse, depression, and suicide (Barzilay et al., 2015).

These considerations suggest that a framework arising from the principles put forward in this chapter have important real-world applications. These deserve future investigation. But we must remember that although these outcomes may appear to be at a collective level, they are transacted by and within individuals, through psychological processes. All the variables discussed in this chapter are manifest and measureable at the individual level. So the concluding principle comes home to roost there.

12. Consequential individual differences in thinking patterns (i.e., mindset) involving the sacred, the secular, and aspects of worldview that give meaning to lives should be part of the standard toolbox of personality psychology. The principles useful for integrating culture with personality partly emphasize moral concepts, but once one deals with cultural differences, it is attitudinal variables that come to the fore. If personality is defined, in part, as characteristic patterns of thinking, would not generalized attitude dispositions like religiousness and conservatism be personality characteristics? Indeed, they are both already found to be (negatively) correlated with one of the factors in the Five-Factor Model (Openness to Experience), and religiosity shows persistent if modest positive associations with Agreeableness and Conscientiousness (Saroglou, 2010). An earlier section pointed out that existing personality-inventory scales like Self-Transcendence and Traditionalism reach into the domain of attitude-dispositions and are likely to show larger cultural differences than behavioral-tendency scales.

There are several arguments for adopting such thinking-pattern tendencies into the family of commonly recognized personality variables. First, in order to exclude them we would need to adjust our definition of personality so that such characteristic patterns of thought would not count. And if we did so, the Openness-to-Experience concept might need to go out as well, as it is primarily a way of thinking. These tendencies are likely to show retest stability similar to that for standard traits and appear to predict important outcome criteria (including well-being and meaning in life). They help link up the personality domain with culture, politics, religion, and so on, extending the interdisciplinary reach of the personality field.

The arguments against might include the following: to a degree, thinking-pattern tendencies need a differing mode of measurement, not being necessarily as reducible to adjectives or short behavior-descriptive phrases. They might be more difficult to infer based on nonverbal behavior than is true for a classic personality trait. It might be more problematic to include them in industrial/organizational settings where political, religious, and cultural neutrality may be desired. And, it might be argued, they belong inherently to other fields and are useful to personality psychologists mainly as outcome criteria. For example, it is interesting that anxiety and guilt-proneness in childhood tends to prefigure political conservatism in adulthood (Block & Block, 2006), but the association does not make this outcome itself a personality attribute. It is not my position that more compartmentalization is needed, but others may wish to make this argument.

The ultimate issue may be whether we wish to have a personality psychology that is linked to the more ubiquitous aspects of culture and not the most variable aspects, or something different: a personality psychology that also interfaces with the deeper sources of cultural variation and the important insights and applications that arise therefrom. So the principle as stated above is incomplete. It should end by saying that certain variables should be part of the standard toolbox of personality psychology if that field wishes to have the strongest and widest applicability to contemporary life.

ENCAPSULATION AND EVALUATION

To review, the principles that have been delineated are the following.

- Culture is not just incidental to human life but profoundly important to it: we are cultural animals.

- Cultural standards center on moral and social norms.

- The central personality dimension is character, that is, the tendency to regulate oneself by those evaluative norms that inspire dutiful action and restraint from pure pursuit of self-interest.

- Variation in moral character, broadly conceived, arises from competing pressures of norms versus what broadly constitutes self-interest.

- A certain skeletal core of moral rules is conserved across cultures.

- Behavioral attributes, as represented in most personality scales, are not a prime locus for cross-cultural differences.

- Among psychological variables, the largest cross-cultural differences pertain to what is religious or “quasi-religious.”

- Any society has two realms of culture: sacred (meaning oriented) and secular/material (instrumentally oriented).

- Societies differ (at any point in time) in the relative priority/predominance of the sacred and secular realms of culture.

- Humans and their societies respond to an existentially difficult situation with a combination of instrumental adaptations and a projected cultural worldview attributing sacredness and providing meaning.

- Sacred culture is a double-edged sword—and the same may be true for secular, material culture.

- Consequential individual differences in thinking patterns (i.e., mindset) involving the sacred, the secular, and aspects of worldview that give meaning to lives should be part of the standard toolbox of personality psychology—if that field desires the greatest degree of applicability.

The foregoing principles are in good part empirically driven, which helps account for their lack of strict deductive logic. However, they might be reduced to a deeper structure that first vitally links humanity to culture, culture to morality, and morality both to character (and thus personality) and to cross-cultural commonalities (what might be styled “ubiquitous culture”). Flipping into the complementary topic of cross-cultural differences (and more “variable culture”), the linkages go from culture to what is religious and quasi-religious, explained in terms of two realms of culture that vary in their relative priority from one context to another, which in turn are seen as responses to the existential human condition, responses that each bring benefits but are prone to impose costs. The final principle advances a recommendation that the topic of “variable culture” indicates individual-difference constructs (such as religious and quasi-religious ones) that should become more important in personality psychology.

It appears that these principles work together mainly to set an agenda for consequential theory and research, by providing indications of how to get at core features and large-effect differences rather than wallowing in inconsequential minutiae in the vast nomological networks of culture and personality. Culture, morality (and self-interest), character, religion, ethnic sentiments, the sacred, the secular, and the existential human condition are shown to be integrally linked in key ways. They should not be segregated and compartmentalized. As that implies, contributions from a range of scientific disciplines are relevant to theory and research around these principles.

To an extent, these principles constitute a broad-level theoretical framework for understanding culture and personality. Taken together, these principles might inspire research that will lead to important gains in prediction, in generalizability across cultures, and in interdisciplinary integration. However, the principles themselves span considerable ground, and more work is needed to fashion a tightly coherent theory from them. At this juncture, they might be seen as constituting a broad umbrella conceptual framework within which useful theories of a specific nature might be generated.

Cross-cultural data affords an opportunity for personality psychology to shake cultural biases and achieve a more panhuman view of the subject matter. Recent developments in the field of personality should inspire cultural psychologists and other students of culture to revisit the classic domain of culture and personality. It is hoped that the perspective provided by the principles reviewed here might help shape good things to come in both research and theory.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Preparation of this chapter benefited from a grant from the John Templeton Foundation.

REFERENCES

Allport, G. W. (1937). Personality: A psychological interpretation. New York, NY: Henry Holt.

The American Heritage Dictionary of the English language, Third edition. (1991). Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin.

Ashton, M. C., Lee, K., & Goldberg, L. R. (2004). A hierarchical analysis of 1,710 English personality-descriptive adjectives. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87, 707–721.

Ashton, M. C., Lee, K., Perugini, M., Szarota, P., De Vries, R. E., Di Blas, L., Boies, K., & De Raad, B. (2004). A six-factor structure of personality-descriptive adjectives: Solutions from psycholexical studies in seven languages. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 86, 356–366.

Ayer, A. J. (1936). Language, truth, and logic. London: Gollancz.

Bailey, F. G. (2001). Treasons, stratagems, and spoils: How leaders make practical use of values and beliefs. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Barzilay, S., Feldman, D., Snir, A., Apter, A., Carli, V., Hoven, C. W., … Wasserman, D. (2015). The interpersonal theory of suicide and adolescent suicidal behavior. Journal of Affective Disorders, 183, 68–74.

Baumeister, R. F. (2005). The cultural animal: Human nature, meaning, and social life. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Block, J., & Block, J. H. (2006). Venturing a 30-year longitudinal study. American Psychologist, 61, 315–327.

Bok, S. I. (1995). Common values. Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press.

Bozek, K., Wei, Y., Yan, Z., Liu, X., Xiong, J., Sugimoto, M., … Khaitovich, P. (2014). Exceptional evolutionary divergence of human muscle and brain metabolomes parallels human cognitive and physical uniqueness. PLoS Biology, 12(5), e1001871. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001871

Brown, D. (1991). Human universals. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

Church, A. T., Katigbak, M. S., Locke, K. D., Zhang, H., Shen, J., Vargas-Flores, J., … Ching, C. M. (2013). Need satisfaction and well-being: Testing self-determination theory in eight cultures. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 44, 507–534.

Cloninger, C. R., Przybeck, T. R., Svrakic, D. M., & Wetzel, R. D. (1994). The Temperament and Character Inventory (TCI): A guide to its development and use. St. Louis, MO: Center for Psychobiology of Personality, Washington University.

Conn, S. R., & Rieke, M. L. (1994). The 16PF fifth edition technical manual. Champaign, IL: Institute for Personality and Ability Testing.

Costa, P. T., Jr., & McCrae, R. R. (1980). Still stable after all these years: Personality as a key to some issues in adulthood and old age. In P. B. Bakes & O. G. Brim (Eds.), Life-span development and behavior (Vol. 3, pp. 65–102). New York, NY: Academic Press.