Much as Toronto does not have a fiscal crisis, Ontario municipalities do not have a spending problem but a revenue problem. In the absence of a concerted pushback, municipal governments can only administer what senior governments create. Ontario municipalities, and Toronto in particular, nevertheless are likely to encounter a number of pressures down the road that will stretch local finances and require political compromises. Never letting a crisis go to waste means using those opportunities as moments to do things that were seemingly unlikely or impossible beforehand (Mirowski 2014). Since the 1970s, it has often been neoliberals who have used moments of crisis for transformational purposes. The steps taken at City Hall since amalgamation, but especially since the onset of the 2008 global economic downturn and election of Rob Ford, take further steps toward the remaking of the local state in neoliberal form. As the role of cities and metropolitan areas increases in domestic and international importance and are seen as cultural and economic centres as well as expressions of political discontent, the need for policy nuance that recognizes the different needs of large and small cities, urban and rural, northern and southern, grows ever more important. Clearly, there is a need to better integrate, coordinate and administer provincial–municipal services delivery, including greater federal participation. Yet the extent of senior-level involvement seems increasingly uncertain as the one-size-fits-all dogma of neoliberalism dominates policymaking. This uncertainty in stable, long-term funding leaves municipalities vulnerable to both changes in financial arrangements and changes in government. For instance, in the summer of 2014 the Ontario Liberal government announced $100 million in annual investments in small towns with fewer than 100,000 persons. In response to these much publicized “new investments,” St. Thomas, Ontario, mayor, Heather Jackson, whose city numbers around 38,000 people, said: “We’re nearing $300 million worth of infrastructure deficit in our community alone … we’re certainly looking forward to being able to access more funds” (Ferguson 2014). The irony of this announcement is that it comes on the heels of reductions to the Ontario Municipal Partnership Fund, which saw transfers payments to northern municipalities down $28 million in 2014, and an expected $35 million in 2015 (amo 2014). These reductions come in the face of forecasted provincial austerity measures extending to 2017–18, which a good many critics, including the Drummond Commission, have noted will require spending cuts deeper than the Harris era. In the face of governments’ continued affinity to neoliberalism and commitment to austerity, the future of municipal financing is unclear. What is certain, however, is that in the absence of greater federal–provincial involvement as well as new municipal revenue-raising capacities and governance autonomy — which, of course, could only be operationalized though successive economic and political struggles — such inaction will heighten the social dislocations across Ontario municipalities.

On October 27, 2014, municipalities across Ontario went to the polls to elect new mayors and regional and municipal representatives. In Toronto, despite a scandal-plagued term, Rob Ford was the first to announce his plans to seek a second mandate. Throughout the summer, rumours swirled that former trustee, city councillor and member of Parliament Olivia Chow would run for mayor. Upon announcing her run, most polls had Olivia Chow favoured to win by a wide margin. A third contender however, John Tory, would eventually secure the mayoral office. Tory, whose grandfather created one of Bay Street’s largest law firms working with the finance, insurance and real estate industries, was well known for his long-standing Conservative ties. A former backroom operative for the Mike Harris Conservatives, he held several leadership positions in the federal Conservative government of Brian Mulroney. In between his stints in politics and the revolving door to the highest echelons of corporate Canada, Tory opened a private legal practice, served as president and ceo of Rogers Media, commissioner of the Canadian Football League, a radio personality and chair of CivicAction. In between these activities, he also ran unsuccessfully for mayor of Toronto in 2003 and served as leader of the Ontario Progressive Conservative Party from 2004 to 2009, and as a member of Provincial Parliament from 2005 to 2009.

After supporting both Rob and Doug Ford in the 2010 election, however, 2014 would be different. While an in-depth appraisal of the election is not possible here, some central issues are nevertheless worth a mention. While Rob Ford was incommunicado during a two-month stint in rehab, Chow and Tory each sought to coalesce voters around an anyone-but-Ford coalition. Chow’s weak political vision, borrowing from the dismal Andrea Horwath ndp provincial platform, presented a “third way” social democratic vision that touted her work with small business and ability to work with conservative Mel Lastman during her time on City Council. Her “moderate,” “sensible” social democratic campaign focused on pocketbook populism, building the fully funded Scarborough light-rail transit and plans to increase the Land Transfer Tax from its current 2 percent to 3 percent on residential properties selling for more than $2 million.

The Toronto and York Region Labour Council, which endorsed Olivia Chow, launched the Our Cities Matter campaign, which sought to publicize issues related to transit, poverty, precarious work, racial equity and the range of services provided by municipal workers, including child and elder care, libraries and environmental initiatives. cupe Locals 79 and 416, as well as the Elementary Teachers of Toronto and Ontario Public Service Employees Union, also supported the Chow campaign. Collectively, unifor, the United Food and Commercial Workers, cupe National and United Steelworkers banded together under the banner “Progressive Toronto” to run a series of ads accusing John Tory of being “out of touch” with women (after suggesting they learn how to play golf to get a pay raise). Like all too many labour campaigns, however, both the Our Cities Matter and Progressive Toronto campaigns stagnated and then vanished, having failed to build an activist base from which to educate and mobilize. As was demonstrated in both the 2009 and 2012 rounds of bargaining, organized labour’s emphasis on backing individual councillors failed to generate a critical mass of elected officials challenging the austerity agenda. Moreover, in the absence of broad-based public backing, councillor support (even where possible) is unlikely to develop without building long-term, community-centred organizational and mobilizational approaches, not campaigns that come and go with elections.

The centrepiece of John Tory’s plan revolved around “SmartTrack,” an $8 billion, twenty-two-stop “surface subway” using existing GO Transit tracks. Despite significant flaws in the plan (Gee 2014; Barber 2014a), the proposal is premised on an additional $5 billion in provincial and federal funding, including $2.6 billion from tax increment financing — borrowing billions in the hope that the property tax base grows enough to pay it off. His plan also called for building a Scarborough subway and lowering property taxes along the route for ten years in order to encourage business development. Other initiatives included a code of conduct and, tellingly, a City task force that would look into restructuring opportunities for Toronto Community Housing Corporation. As a result of being diagnosed with cancer six weeks before the election, Rob Ford dropped out of the mayoral race, announcing his intention to run for his old seat on City Council. His brother, Doug Ford, took his place as heir to Ford Nation. His campaign essentially repeated the dogma of his brother’s 2010 election — going after the “gravy,” keeping taxes low, spurring business development, taking a tough stance with city unions and building subways, not light-rail transit.

On election day, John Tory was elected mayor with 40 percent of the vote, while Doug Ford and Olivia Chow received 34 and 23 percent of the vote. In an attempt to present himself as non-ideological, throughout his campaign John Tory vowed not to steer the city to the left or right but forward. Olivia Chow failed to capitalize on her initial popularity, running a cautious, middle-of-the-road campaign, while Doug Ford seemed to lack the popular charisma characteristic of his brother Rob, who retained a seat on Council. Tory also seemed to benefit from the anyone-but-Ford vote as the Chow campaign focused much of their energy and resources going after the Ford brothers, as opposed to the gaps in John Tory’s SmartTrack or his stated affinity to the Ford administration’s political program minus the scandals.

Through the 2014 campaign, John Tory denied that both white privilege and the deep currents of racism in Toronto exist. This was in spite of many instances to the contrary, such as the experience of Munira Abukar, a Muslim woman and community activist whose campaign signs were vandalized saying “go back home,” racist and homophobic slurs against Kristen Wong-Tam, who was running for Council re-election, and repeated racial and gendered intimations and explicit remarks directed at Olivia Chow. These overtures culminated in a shockingly inappropriate Toronto Sun cartoon by Andy Donato portraying Chow as a racial caricature and Mao-style communist riding the coattails of her late husband, Jack Layton. Toronto’s Bay Street community lined up behind John Tory, who attracted some $2.5 million from donors, while Olivia Chow raised $1.7 million and Doug Ford around $300,000. The Toronto Taxpayers Coalition (Peat 2014) mounted a Stop Chow Now campaign, arguing that she made former Mayor David Miller look like a fiscal conservative, warning: “The left is pulling out all the stops to recapture the city and restore a tax and spend socialist government.” In his early days, John Tory has touted privatizing public services, pro-business development and tax “incentives,” as well as holding the line on taxes and reaching a “fair” deal with the city’s unionized workers. It may very well turn out to be that with the election of John Tory, Toronto merely exchanged an incompetent conservative with a sophisticated one.

Of the forty-four councillors making up Toronto City Hall, thirty-six out of thirty-seven incumbents won their seats, seven councillors are new and one is last term’s mayor. With this election, the conservative agenda has been largely strengthened: new councillours include Stephen Holyday, son of former councillour and provincial Conservative member of Parliament Doug Holyday; investment firm director Justin Di Ciano; former right-wing Liberal member of Parliament Jim Karygiannis; and former police officer Jon Burnside. As journalist Edward Keenan (2014) has written, when it comes to appointing City Council’s executive and chairs of committees and agencies, John Tory’s appointments “read like a declaration of war against city council’s progressives.” In a particularly telling appointment, John Tory chose far-right councillor Denzil Minnan-Wong as deputy mayor and to sit on the boards of Invest Toronto, Build Toronto and Waterfront Toronto — agencies he’s long rallied against for not pushing an expansive enough pro-development-at-all-costs agenda. Furthermore, Minnan-Wong will head the Civic Appointments Committee, charged with overseeing appointments from everything to libraries, community centres and the Toronto Parking Authority, as well as head of the Strike Committee that selects members of Council committees and heads for the labour relations committees that negotiate with the city’s unions. If Minnan-Wong’s long tenure as councillor and his actions during the 2009 and 2012 rounds of bargaining are any indication, far from a new “united Toronto” and Council, Tory has fired the first shots in what may be the opening salvo of class warfare on a level perhaps previously unseen.

Despite a record voter turnout of 61 percent, the consolidated conservative coalition at City Hall also raises concerns about the lack of gender and racial diversity. The proportion of non-white councillours remains the same as it was ten years ago at 13 percent, while the proportion of women serving has fluctuated over that time between a quarter and one-third of total Council seats. Curiously, in a poll released less than a week to go before the election, some 19 percent of Ontario New Democratic Party supporters said they planned to support Doug Ford, while 24 percent said they planned to support John Tory. With 43 percent of provincial New Democratic supporters vowing to cast a ballot for one conservative mayoral candidate or the other, the inability of so-called progressive candidates to craft a message that captures the democratic imagination and counters the neoliberal rhetoric of supposedly post-ideological politics, speaks to the need to rebuild and redefine what is meant by Left politics in an era when the ideological spectrum has shifted so far to the right.

As opposed to social democracy with “sober senses,” then, what is needed is a Left movement made up of labour and social movement dissidents, rooted in the communities they serve, putting forward a vision of engaged democratic participation, social justice and emancipatory politics that offers promise and inspiration to those engaged in struggles of various kinds to create a better local politics and with that a better world. Paradoxically, as David Hulchansky (2014) has argued:

Toronto’s electoral divide, however, is not along partisan political lines. The divisions are based on socio-economic, ethno-cultural and skin colour characteristics … The loss of well-paying unionized job with benefits following free trade agreements, global financial markets, and “efficiencies” in corporations and governments (e.g., contracting-out to firms paying minimum wage) have decimated the once large and growing group in the middle of the income distribution. We have a polarized labour market, with many more at the bottom and a few more at the top.

The class divisions at the heart of the 2014 campaign, much like the class politics in the making of the megacity since 1998 more generally, have much to do with the social exclusions at the core of neoliberal governance arrangements. As John Lorinc (2014) has argued, “Resident associations and business improvement areas wield real clout with councillors, while tenant councils, where they exist, simply do not.” This class exploitation is multifaceted across race, gender, ability, ethnicity, sexuality and other subjectivities, yet has continuously reproduced itself in post-amalgamation Toronto.

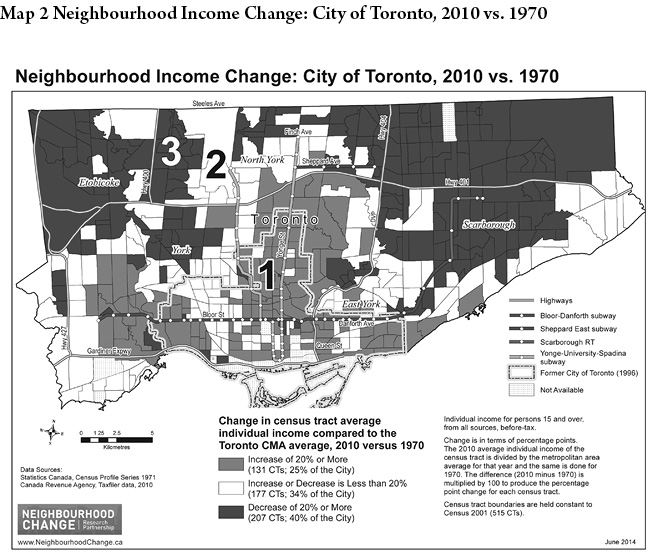

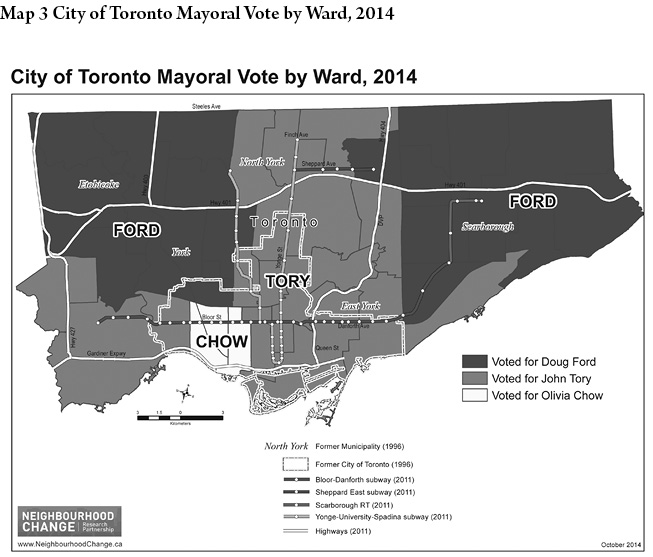

As Maps 2 and 3 illustrate, this spatial mismatch is further illustrated through the inverted “T” pattern flowing from north of the city to the south, which emerged more clearly since the 2014 election (Tencer 2014). The inside of the “T,” what Hulchanski (2010) has referred to as City 1, contains most of the city’s wealthiest enclaves and gentrifying areas. City 2, formerly characterized by middle-income earners, has been shrinking rapidly; Ford, Chow and Tory more or less split this area of the city. Doug Ford, however, took nearly all of City 3, Toronto’s low-income, largely immigrant populations excluded from both the “new economy” and public services, particularly transit (Taylor 2014; Haider 2014). Thus, while the cult of personality and public transit dominated the election campaign, this election was as much about declining access to public services and income inequality as it was about urban-suburban voting patterns:

It took thirty years to divide Toronto into three cities. And as this week’s [October 27, 2014] election vividly demonstrated, those social divisions produce a divided voting pattern. Over time, it is possible to incrementally reverse these trends, year after year. But this long-term goal can only occur if city council, and a mayor with a bully pulpit, are willing to not only advocate for change, but also take meaningful steps that will help create a city with fairer opportunities for all, thereby reducing the divide writ large on our electoral map. (Hulchanski 2014)

In this context it is important to recall that Mayor Mel Lastman (1998–2003) used the reduction in federal and provincial transfer funds to municipalities as a political rationale to harmonize downwards wages and increase workplace precarity. Rather than depart from the neoliberal project, Mayor David Miller (2003–2010) sought to bolster competitiveness, enhance entrepreneurial opportunities and promote Toronto as a “global city,” ultimately seeking concessions from workers as a disingenuous trade off against public services. Rob Ford and Council (2010–2014) extended the assault against public services and civic workers by raising user fees, selling off public assets, contracting-out and extracting further concessions from employees. Peck and Ticknell (2012: 248) argue:

Progressive “postneoliberal” strategies will be going nowhere, practically or metaphorically, if they continue to privilege the local over other horizons of action and intervention. Constraining the operation of neoliberalism … at extra-local scales, and making room for the propagation of reciprocal and cooperative extra-local relations (including active sociospatial redistribution, neoliberalism’s antithesis) must be a defining feature of progressive movements beyond market rule.

Building a movement for social change cannot come from the top down, but must arise through collective political struggles across the many cleavages of the working class. This has been organized labour’s, as much as other social movements’, most effective tool for real change. Considering the multiplicity of pressures, time will tell if a major resistance is in the cards.