Chapter 4

Colossians 1:24–2:5

Literary Context

This section follows the christological confession in 1:15–20, which has provided the critical foundation for this entire letter. In the form of a hymn, the exalted status of Christ is affirmed through a description of both his role in creation (vv. 15–16) and his death and resurrection (vv. 18b–20), which climaxes in his role as the sustainer of all things (vv. 17–18a). Paul emphasizes how the death of Jesus in his physical body has completed the act of reconciliation through which believers can approach God. In response to this act, Paul also urges the Colossians to stand firmly in the gospel that they had received.

The status of Paul as Christ’s “servant,” noted at the end of the previous section (1:23), becomes the focus of this next section. The gospel now centers on the ministry of one particular apostolic bearer of this gospel. This connection between the cosmic Christ and the particular servant explains a number of parallels that exist between these two sections: suffering (1:24, 29; 2:1; cf. 1:18, 20), physical body (1:24; cf. 1:22), church (1:24; cf. 1:18), and Christ (1:24, 27, 28; 2:5; cf. 1:15–20).

Although this section focuses on Paul’s unique role as an apostle, he first makes it clear that he is not the center of the gospel message. His role within God’s wider plan is to be the “servant of the church” (v. 25). Second, in a section flooded with the first person singular, the appearance of the first person plural pronoun “we” (ἡμεῖς, v. 28) must not be missed. Rather than simply a “stylistic variation,”1 this pronoun emphasizes that Paul is not the only one proclaiming the gospel of Christ. Third, the emphasis in this section is on his “suffering” (vv. 24, 29; 2:1), not on his “power,” since that power only comes from Christ (v. 29).

Just as the previous section contains both a summary of the gospel (1:15–20) and an appropriation of such a gospel (1:21–23), this section also contains two subsections. The first one (1:24–29) introduces Paul’s own mission and role, and he draws attention to the “mystery” that has now been revealed (vv. 26, 27). In the second subsection, Paul explains that his apostolic call and mission allows believers to be assured of their knowledge of and commitment to this “mystery” (2:2). At the end (2:5), Paul refers to his absence, which reminds his audience that this letter represents his presence and authority.2 This leads into the next major section (2:6–15), where Paul addresses the specific concerns the Colossians are facing in their own context.

This section that focuses on the role of Paul is not simply an excursus; instead, it forms an integral part of his argument. First, in light of Paul’s emphasis on God’s plan, the progression from God the Father (1:3–14) to Christ the Son (1:15–23) that leads to the present section on Paul the servant of Christ (1:24–2:5) becomes understandable. In the next section, the focus is then shifted to the recipients of the gospel that the apostles are preaching (2:6–4:1). Second, in emphasizing his unique role in God’s plan, Paul also reminds his audience to submit to the gospel for which he has labored (1:29; 2:1). This then prepares for the strong critique of the false teachers in the next section. Third, in emphasizing his own “suffering” and “struggles” (1:24, 29; 2:1), Paul may also be preparing the Colossians to participate in this struggle as they seek to be faithful to the gospel (2:16; 4:2). Finally, some have also detected a subtle reaction against the false teachers in this section.3 Instead of speculations and misleading visionary reports, Paul reminds the audience that they should rely on the secure “knowledge” that is anchored in Christ himself (2:2).

At the end of this section, the reference to Paul’s absence also reminds his audience that this letter represents his presence and authority (2:5).4 Though absent in flesh, Paul as the mediator of the gospel message continues as he urges the Colossians to stand firm in their “faith in Christ” (2:5). This urge becomes powerful precisely because his absence testifies to his own faithfulness to the gospel as he repeatedly reminds his audiences that he is faithful to this gospel for which he is “in chains” (4:3, 18).

- III. Climactic Work of the Son (1:15–23)

- A. Supremacy of Christ (1:15–20)

- B. Response to the Work of Christ (1:21–23)

- IV. Apostolic Mission of Paul (1:24–2:5)

- A. Paul’s Suffering in the Plan of God (1:24–29)

- B. Paul’s Toil for the Local Churches (2:1–5)

- V. Faithfulness of the Believers (2:6–4:1)

Main Idea

As a servant of Christ and his church, Paul labors as a steward of the plan of God, a plan that reveals the glorious mystery that is relevant for all humanity. For those in Laodicea and Colossae in particular, Paul points to the urgent need to be grounded in the knowledge that is in Christ so that they will not be deceived by false teachings.

Translation

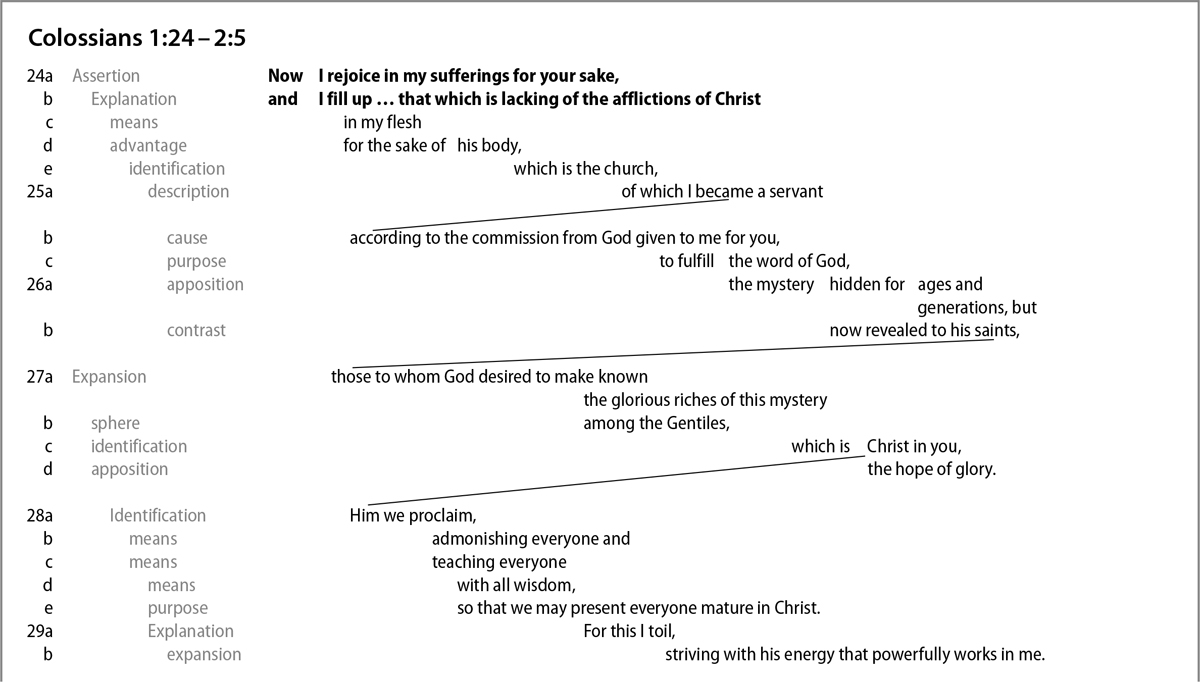

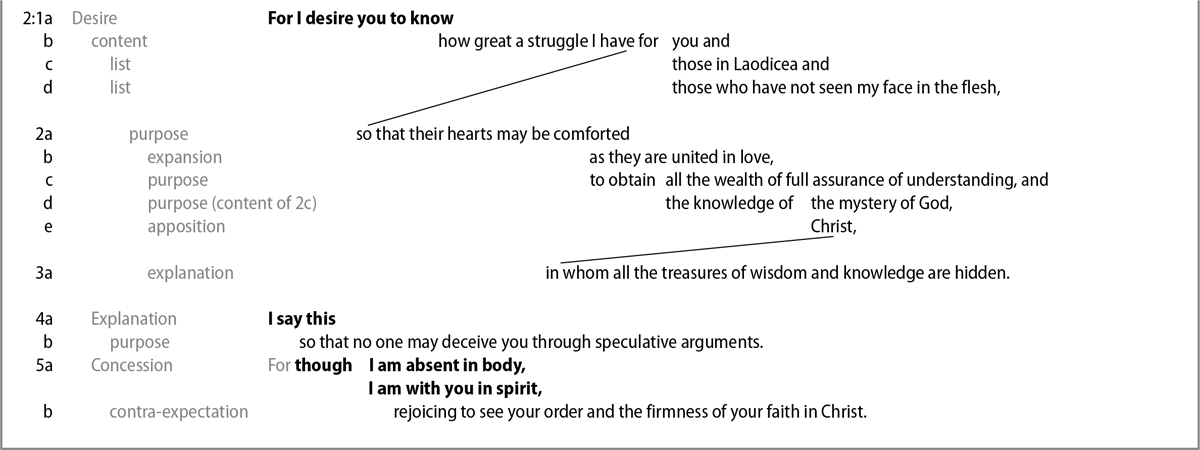

Structure

Various proposals have been offered in mapping the development of Paul’s thought in this section. These include a single or double chiastic structure.5 While a consensus may not be possible, three structural markers are clear. First, the recurrence of rejoicing (χαίρω/χαίρων) and physicality (τῇ σαρκί) in both 1:24 and 2:5 serve as an inclusio to delineate this section, which focuses on Paul’s apostolic mission.

Second, in both subsections (1:24–29 and 2:1–5), the focus is on the “mystery” of God (1:26–27; 2:2–3). This points to both the center of Paul’s mission as well as the urgency of his message for his audience.

Third, in light of the parallelism between the two subsections that deal with Paul’s struggles (1:24–25; 2:1), the mystery of God (1:26–27; 2:2–3), and the mission of Paul among the apostles (1:28–29; 2:4–5), one difference is also clear: 1:24–29 focuses on Paul’s general stewardship of the gospel, and 2:1–5 focuses on Paul’s specific labor for the Colossians and Laodiceans. These two related subsections recall the previous section, where one also finds a general christological confession (1:15–20) and a specific application particularly relevant in one local context (1:21–23).

Paul begins by noting the role of his suffering in the wider plan of God (1:24–25). Through these difficult verses, the eschatological significance of Paul’s mission is clarified. He then shifts the attention to the mystery of God, one that is particularly relevant in his mission to the Gentiles (1:26–27). With a shift to the plural pronoun in 1:28, Paul identifies himself with other servants of the gospel whose mission is to present everyone mature in Christ (1:29). Paul concludes by noting the source of his power, which can be found in Christ.

In the second subsection, Paul likewise begins with his struggles, but he now focuses on his labor for those in Colossae and Laodicea (2:1). The goal of such labor is that they may be united in love and understanding so that they can fully comprehend the mystery of God (2:2–3). With a firm grasp of that mystery, Paul expresses his wish that they withstand the challenges of the false teachings (2:4–5).

Exegetical Outline

- I. Paul’s Suffering in the Plan of God (1:24–29)

- A. Paul’s suffering for the sake of the church (1:24–25)

- B. Mystery of God revealed (1:26–27)

- C. Apostolic mission (1:28–29)

- II. Paul’s Toil for the Local Churches (2:1–5)

- A. Paul’s struggles for the Colossians and Laodiceans (2:1)

- B. Full understanding of the mystery of God (2:2–3)

- C. Epistolary mission of Paul (2:4–5)

Explanation of the Text

1:24a Now I rejoice in my sufferings for your sake (Νῦν χαίρω ἐν τοῖς παθήμασιν ὑπὲρ ὑμῶν). Paul here shifts his attention to his apostolic role as one who suffers for the Gentile believers. “Now” (νῦν) may simply signify the logical progression of Paul’s argument (1 Cor 5:11; 12:20),6 although in this context with the reference to his “sufferings” Paul may have his present imprisonment in mind (cf. 4:3, 10, 18). In light of the emphasis on his involvement in the unfolding of the eschatological plan of God, this “now” may also point to the realization of the age of fulfillment. This reading is supported by the reappearance of “now” (νῦν) in v. 26 in reference to the revelation of God’s mystery.

“I rejoice in my sufferings” points to Paul’s practicing of what he teaches in 1:11–12, where he encourages the Colossians to give thanks to the Father joyfully even when they need to be patient and steadfast. The note on “rejoicing” reappears at the end of this section in 2:5, where Paul shifts the focus to the life and behavior of the audience. These two notes bracket the intervening material that centers on the relevance of Paul’s suffering for the Colossians.

Although the Greek text does not specify that Paul is referring to his own suffering,7 the context makes it clear that he is the implied subject of this verbal noun (“my sufferings”). The coexistence of joy and suffering can be found elsewhere in Paul (cf. 2 Cor 6:10), especially when this suffering is related to his proclamation of the gospel (cf. Phil 1:18–19). This reference to suffering highlights its importance in his apostolic ministry (cf. Rom 5:3; 2 Tim 1:12; 3:11). It also points to Paul’s imitation of Christ’s suffering (cf. 1 Thess 1:6) and to his authority as an apostle called to this path of suffering (cf. Acts 9:26).

In this context, Paul’s rejoicing is not simply because he is suffering, but because he is suffering “for your sake” (i.e., for the sake of the Colossians; cf. also 2 Cor 1:6). But this connection is still surprising here because it is not immediately clear as to how Paul’s suffering will affect a community that he had neither founded nor visited. The end of this verse, which identifies the audience as part of the “body” of Christ, helps to alleviate the initial shock of this verse.8 Moule, who accepts this identification, further suggests that Paul is referring to the Gentiles in particular, of which the Colossians are a part, and “Paul’s sufferings were incurred largely as a result of his apostleship to them.”9 The parallel in Eph 3:13 further supports this reading. The second part of this verse, therefore, serves to explain how Paul’s suffering affects the Gentiles.

1:24b-c And I fill up in my flesh that which is lacking of the afflictions of Christ (καὶ ἀνταναπληρῶ τὰ ὑστερήματα τῶν θλίψεων τοῦ Χριστοῦ ἐν τῇ σαρκί μου). Paul now specifies that he is completing that which remains to be filled up in the predetermined messianic afflictions that are taking place in the eschatological era. While this clause is meant to explain Paul’s suffering for the sake of the Colossians,10 the difficulties embedded in this verse have often limited the explicatory power of this clause. Before providing various options in understanding this entire clause, the various elements should first be analyzed.

The verb “I fill up” (ἀνταναπληρῶ) appears only here in the NT, but the related form, with only one prepositional prefix, “to fill up/to complete” (ἀναπληρόω), has appeared together with the references to “that which is lacking” (τὰ ὑστερήμα[τα]) in 1 Cor 16:17; Phil 2:30.11 Whether the second prepositional prefix ἀντί (“instead of,” “on behalf of”) adds anything to this verb is unclear. Taking into account the full force of this preposition, some have translated the verb as “to fill up or complete for someone else.”12 But others have considered the two verbs as synonymous (“fill up,” NKJV, TNIV, NIV).13 In light of Paul’s earlier reference to “for your sake” (ὑπὲρ ὑμῶν) and the phrase that follows, “for the sake of his body” (ὑπὲρ τοῦ σώματος αὐτοῦ), a certain sense of representation is likely present although an exclusive vicarious significance cannot be deduced from the presence of this prefix.

In the Greek text, “in my flesh” (ἐν τῇ σαρκί μου) follows “the afflictions of Christ,” and this word order has encouraged some to take this prepositional phrase as modifying Christ’s afflictions: “I am completing what is lacking in Christ’s-afflictions-in-my-flesh for the sake of his body.”14 With the absence of a definite article (τῶν) before this prepositional phrase, however, it is best to take this phrase in an adverbial sense modifying the verb “is lacking” (as most contemporary versions do). Moreover, the placement of this phrase is probably dictated by the next phrase in the Greek text, “for the sake of his body” (ὑπὲρ τοῦ σώματος αὐτοῦ), as the two phrases together aim at evoking the earlier reference to “his [Christ’s] body of flesh” (τῷ σώματι τῆς σαρκὸς αὐτοῦ, 1:22). In focusing on his own physical suffering, not only does Paul point to the importance of the continuation of Christ’s work on the historical plane; he also points to the proper way to use one’s body within the greater salvation plan of God. This emphasis may in turn anticipate his criticism of the false teachers, who encourage the misuse and mistreatment of one’s “body” and “flesh” (2:23).

“That which is lacking of the afflictions of Christ” (τὰ ὑστερήματα τῶν θλίψεων τοῦ Χριστοῦ) is perhaps one of the most difficult phrases to interpret in this letter. “That which is lacking” can point to a relative degree of insufficiency or a definite gap that has to be filled. Linking this deficiency with the “afflictions of Christ” causes confusion with the exact sense of this phrase. The function of the genitival phrase “of Christ” (τοῦ Χριστοῦ) lies at the center of this debate. The possible renderings include “Christ’s own afflictions” (possessive genitive), “afflictions for Christ” (objective genitive), “afflictions in regard to Christ” (genitive of reference), or “messianic afflictions” (attributive genitive). Most contemporary commentators choose either the possessive genitive or attributive genitive.

(1) Christ’s own afflictions. For those who consider this phrase as referring to Christ’s own afflictions, some have suggested that the suffering of Christ was indeed insufficient for the salvation of his followers.15 This interpretation, however, is unlikely in light of the repeated references to the sufficient and final salvific work of Christ (1:18–20, 22; 2:9–10, 14–15).

Others see this as an exaggerated statement that aims at exalting the role of Paul by one his disciples or admirers. This portrayal of Paul becomes a “mirror-image of the portrait of Christ,”16 and it appears only after Paul’s own martyrdom, which prompted some “to interpret Paul’s death theologically.”17 This reading assumes that the author is a poor student of Paul’s own theology who ends up with a portrayal that is in conflict with the rest of this letter with its emphasis on the final sufficiency of Christ.

Others distinguish between the various types of sufferings of Christ. While the final “sacrificial efficacy” of Christ’s suffering cannot be doubted, the “ministerial utility” of such suffering remains an object of imitation.18 It is unclear, however, whether any ancient examples can be cited for the coexistence of the two types of the suffering within the same text, and whether the audience would be able to detect such a subtle distinction.

Noticing the word order in the Greek text, some take the phrase “in my flesh” (ἐν τῇ σαρκί μου) as modifying “the afflictions of Christ” (τῶν θλίψεων τοῦ Χριστοῦ). Therefore, it is not Christ’s suffering that is deficient: “the defect that St. Paul is contemplating lies not in the afflictions of Christ as such, but rather in the afflictions of Christ as they are reflected and reproduced in the life and behavior of Paul, his apostle.”19 As noted above, this reading of the Greek text is problematic. Moreover, while in Phil 3:10–11 Paul does express his conviction to participate in the suffering of Christ,20 the parallel with our present verse is not exact especially in light of the absence of the critical reference to Paul’s filling up “that which is lacking” in Christ’s affliction.

Finally, some who take the phrase “of Christ” as a possessive genitive nevertheless see the believers as standing behind this reference to Christ. This can be understood as a case of corporate identity, where the community of Christ is represented by Christ himself.21 Others point to the mystical union between Christ and his followers.22 This reading is again problematic in light of the clear distinction made between Christ and both the creation and the church in the preceding hymn (1:15–20) and in the rest of the present verse.

(2) Messianic afflictions. To take the genitival phrase as an attributive genitive and thus see “Christ” as a title (“Messiah”) that modifies the noted afflictions allows Paul to affirm the presence of a deficiency that is related to Christ the Messiah, but not one for which Christ is responsible.23 Jewish texts testify to the belief in the time of Paul that tribulations and sufferings would precede the arrival of the end of times (Dan 7:21–27; 12:1; Jub. 23:13; 4 Ezra 4:36–37; 13:16–19; cf. also NT texts, such as Mark 13:20; Rev 7:14; 12:13–17). The idea of a definitive amount of sufferings to take place during this period is also assumed in Rev 6:9–11. In Paul, the language of “birth pangs” is also used to refer to the suffering that precedes the final consummation of God’s salvation among his people (Gal 4:19), and the relationship between his mission and the parousia is also noted in his earlier letters (cf. Rom 11:25–32; 2 Thess 2:6–7). In light of this background, Paul’s reference to “that which is lacking of the afflictions of Christ” may then point to the amount that remains to be filled up in the predetermined sufferings that are to take place in the end times.24

This reading is further supported by a number of observations: (a) the reference to “that which is lacking” may presuppose a predetermined quota; (b) the word for “afflictions” (θλίψεων) is never used by Paul for Christ’s own atoning suffering; (c) the presence of a definite article (τῶν) before “afflictions” may point to a precise kind of suffering that Paul has in mind; (d) the note on the necessity of Paul’s suffering as related to his calling as an apostle suggests the idea of a quota (1 Cor 4:9; 2 Cor 2:14; 4:11);25 (e) this present paragraph is flooded with eschatological references, especially in v. 26;26 (f) while many concede that “Colossians does not specify how Paul’s suffering benefits the church,”27 this reading provides at least one possible link when his suffering fulfills this quota, thus hastening the fulfillment of God’s work in history and benefitting even those whom he had never met.28

The purpose of evoking such messianic afflictions may be twofold. First, Paul seeks to establish his authority as an apostle to the Gentiles who suffers for them in proclaiming the powerful gospel. This allows him to provide the warnings and encouragements that follow. Second, perhaps in anticipating the false teachers who emphasize immediate eschatological experience through spatial ascent, Paul emphasizes the significance of the temporal framework of salvation history. Ultimate fulfillment and union with Christ await when the promised final consummation is realized. A similar strategy can also be detected in 3:1–4 (see comments there).

1:24d-e For the sake of his body, which is the church (ὑπὲρ τοῦ σώματος αὐτοῦ, ὅ ἐστιν ἡ ἐκκλησία). This phrase recalls “for your sake” (ὑπὲρ ὑμῶν) in 1:24a as it identifies the audience as part of the universal church. In the christological hymn, Paul has already identified Christ as “the head of the body, the church” (v. 18). The reappearance of this description therefore also connects Paul’s ministry with Christ’s, while emphasizing that Christ is the authority under which he serves. This phrase also links this section with the conclusion of the previous section, where Paul affirms his role as a “servant” of the gospel (v. 23), an affirmation that will be reiterated in the next verse. Both the unique status of Paul the apostle and his subordinating role to the authority of Christ are emphasized throughout this section.

1:25a Of which I became a servant (ἧς ἐγενόμην ἐγὼ διάκονος). The relative pronoun “of which” refers back to “the church” and points to Paul’s self-portrayal as one who is not only subservient to the gospel but also carries the distinct honor to speak on its behalf. This section (vv. 25–29) provides significant elaboration on the purpose of the suffering noted in v. 24. Note also the presence of two phrases that point back to the previous discussions: “of which I became a servant” recalls v. 23, and “to fulfill the word of God” at the end of v. 25 parallels Paul’s mission as just noted in v. 24.

In v. 23, Paul claims to be “a servant” (διάκονος) of the gospel; here, however, Paul is “a servant” of the church. The connection between the gospel and the church has already been established in v. 6, where it is stated that the gospel bears fruit and grows “in the whole world.” The existence of the universal church testifies to the power of this gospel. In this context, since the church is considered to be “the body” of Christ (v. 24), to be a servant of this body is to serve the “head” of this body (v. 18). Elsewhere in this letter, Paul also names Epaphras (1:7) and Tychicus (4:7) as “fellow slaves” (σύνδουλος) of Christ. In all three cases, servitude may be implied, but the word may also point to the honor of one who serves as the spokesperson for one in power.29

1:25b-c According to the commission from God given to me for you, to fulfill the word of God (κατὰ τὴν οἰκονομίαν τοῦ θεοῦ τὴν δοθεῖσάν μοι εἰς ὑμᾶς πληρῶσαι τὸν λόγον τοῦ θεοῦ). Paul continues his self-portrayal by locating himself within the wider plan of God. “The commission” (τὴν οἰκονομίαν) can refer to an office, and some have taken the phrase “the commission from God” as referring to “the office of God,” thus the “divine office” (RSV) of the apostle Paul.30 The parallel in 1 Cor 9:16–17 is important, however, especially when the word is used in both contexts to refer to the call and responsibility of Paul as one who must proclaim the gospel to the Gentiles. Therefore, “the commission” is perhaps the best translation, understood as “the commission God gave me” (TNIV, NIV).31 The word οἰκονομία originated in a household context (cf. Luke 16:1–4), and it became a particularly relevant term when the early Christians found their roots by gathering around the “household” (οἶκος), as noted in this letter (4:15; cf. Rom 16:5; 1 Cor 11:34; 16:19; 1 Tim 3:5).

The parallel in Eph 3:2 further explains that this commission is “the commission of God’s grace” (pers. trans.). In Colossians, the close connection between the powerful “word” (ὁ λόγος), “gospel” (τὸ εὐαγγέλιον), and “grace” (ἡ χάρις) in Col 1:5–7 has already paved the way for Paul’s description of his own mediatorial role in the outworking of God’s plan in history. The prepositional phrase “for you” (εἰς ὑμᾶς) anticipates v. 27, where Paul points to the revelation of the mystery of God to the Gentiles. Reading vv. 25 and 27 together, Paul is reiterating the fact that he is an “apostle to the Gentiles” (Rom 11:13; cf. Gal 2:8), “appointed a herald and an apostle … and a true and faithful teacher of the Gentiles” (1 Tim 2:7).

The clause “to fulfill the word of God” is similar to Paul’s description of his own mission in v. 24.32 The word “fulfill” (πληρῶσαι) has been taken in various ways. Some take it in an adjectival sense as modifying “the word of God” (“proclaiming his entire message to you,” NLT). Perhaps closer to the intention of Paul, others take it in an adverbial sense in the depiction of the full reception of the word (“to make the word of God fully known,” ESV), or in the portrayal of the mission to preach the word (“so that I might fully carry out the preaching of the word of God,” NASB; cf. NET). But in light of the use of a related term in v. 24 (“I fill up,” ἀνταναπληρῶ), the full force of this infinitive has to be recognized especially in reference to that which needs to be filled up.

Paul is not simply aiming to fill the audience with the word of God; instead, Paul is focusing on the need to fulfill the mission of God’s word. As that word is destined to grow and bear fruit “in the whole world” (v. 6), Paul, as the bearer of this word, is to participate in fulfilling its mission. In v. 27, he further explains that this fulfillment is to be found in proclaiming the gospel among the Gentiles. This is similar to Paul’s christological confession in 1 Tim 3:16, which portrays the mission of the Son:

He appeared in the flesh,

was vindicated by the Spirit,

was seen by the angels,

was preached among the nations,

was believed on in the world,

was taken up in glory.33

In language closer to this particular verse, one can also point to Rom 15:19: “From Jerusalem all the way around to Illyricum, I have fully proclaimed [from πληρόω] the gospel of Christ.” This comment is not to boast about the effectiveness of Paul’s own ministry; the focus is rather on the inherent power embedded in the mission of the word.

The significance of the parallels between Paul’s need to “fill up” that which is lacking in the afflictions of Christ in v. 24 and his commitment to fulfill the word of God in this verse should not be downplayed. To suffer is part of the proclamation of the word of God. This suffering for the gospel is, after all, the content of Paul’s call as conveyed through Ananias: “This man is my chosen instrument to proclaim my name to the Gentiles and their kings and to the people of Israel. I will show him how much he must suffer for my name” (Acts 9:15–16).

1:26a The mystery hidden from ages and generations (τὸ μυστήριον τὸ ἀποκεκρυμμένον ἀπὸ τῶν αἰώνων καὶ ἀπὸ τῶν γενεῶν). Paul now describes his ministry in relation to the mystery in the eschatological promises of God. “The mystery” (τὸ μυστήριον) stands in apposition to “the word of God” (τὸν λόγον τοῦ θεοῦ) in the preceding clause, and as such it explains the content of this “word.” “The mystery” may evoke the “mystery cults” in the mind of the Gentile audience, but most scholars are now convinced that the context clearly points to the Jewish background of the term.34 Moreover, if Paul intends to refer to the “mystery cults,” he would have used the plural instead. For the ancient audience, however, it is possible that some may have seen this word as acquiring a polemical sense as this new “mystery” is to replace the mystery cults with which they were familiar.35

To appreciate the richness and complexity of this term, one must begin with its use in the Old Testament apocalyptic traditions. In Daniel, in particular, the “mystery” refers to the plan of God that will find its fulfillment in the future (Dan 2:18, 19, 27, 28, 29, 30, 47). This use can also be identified in the later Jewish literature.36 In light of this background, Paul’s use of this term here highlights both the continuity with the prophetic traditions as well as the discontinuity that this gospel of the eschatological age signifies.37 This mystery thus affirms the consistency of God’s plan for his people as well as the surprising elements that can only be revealed with the arrival of the climax of salvation history in the life and death of Jesus Christ.

A close parallel to Paul’s description of this “mystery” can be found in 1 Cor 2:6–7, where one finds references to wisdom (cf. v. 28), maturity (cf. v. 28), the ages, and the hiddenness of the mystery in the context of the revelation of God’s glory in an eschatological age: “We … speak a message of wisdom among the mature, but not the wisdom of this age or of the rulers of this age, who are coming to nothing. No, we declare God’s wisdom, a mystery that has been hidden and that God destined for our glory before time began.”

In Paul, the “mystery” can refer to the entire gospel (Rom 16:25) or one aspect of it (1 Cor 15:51).38 In the present context, this “mystery” centers on the inclusion of the Gentiles (v. 27) as Paul presents “everyone” mature in Christ (v. 28). This aspect of the “mystery” can also be found in Rom 11:25 and is elaborated in Eph 3:1–9. For Paul, this “mystery” is one aspect of the gospel, but it draws from its center as it points to the powerful work of God in the death of Christ that breaks down ethnic and cosmic barriers in the creation of the one people.

“Hidden” is a concept inherent in the term “mystery,” but it also anticipates the time of revelation. “For ages and generations” can have a temporal sense or a personal sense. In the LXX, “ages” and “generations” are often synonymous, referring to a lengthy period of time (cf. Exod 40:15; Lev 3:17). In this context, however, some point to the possible parallel in Eph 2:2 and the reference to the “rulers of this age” in 1 Cor 2:6–13 and suggest that the “ages” and “generations” are to be understood as the personified Aeons.39 The translation “from ages and from generations” (KJV, NKJV) leaves room for this personified reading. The temporal particle “now” that follows, however, supports a temporal reading.

1:26b But now revealed to his saints (νῦν δὲ ἐφανερώθη τοῖς ἁγίοις αὐτοῦ). The contrast between the past and the present is made clear with this verse, which announces the revelation of God’s eschatological mystery. In light of the reference to the “ages” and “revelation,” “now” (νῦν) likely points to the entire messianic era initiated by the death and resurrection of Christ (vv. 18, 20) and actualized in the proclamation of the gospel (v. 25). God is the implied agent of the passive verb “revealed” (ἐφανερώθη). This verb means “disclosed” (TNIV, NIV), but it is closely related to a similar term “revealed” (ἀποκαλύπτω)40 and therefore can justifiably be translated as such in this context (cf. NKJV, NRSV, ESV, NLT).

Unlike some recent attempts to interpret “his saints” (τοῖς ἁγίοις αὐτοῦ) as “those to whom the Gospel was first revealed and entrusted,”41 this term most likely refers to all believers in light of the consistent use of this term elsewhere in this chapter (vv. 2, 4, 12). Moreover, Paul later argues against the focus on private and selective revelatory experience (2:18) while affirming that all believers are the beneficiaries of such eschatological acts of revelation (2:6–15; 3:3–4). To Paul, therefore, the revelation of mystery is not simply “an essentially religious experience,”42 but the act of God in history for all who respond to the proclamation of God’s word.

1:27a-b Those to whom God desired to make known the glorious riches of this mystery among the Gentiles (οἷς ἠθέλησεν ὁ θεὸς γνωρίσαι τί τὸ πλοῦτος τῆς δόξης τοῦ μυστηρίου τούτου ἐν τοῖς ἔθνεσιν). Paul further identifies the recipients of the revelation of the mystery. “Those” (οἷς) goes back to the “saints” who receive this revelation (v. 26). The verb “desired” (ἠθέλησεν) indicates “the freedom of the divine will”43 and points back to 1:1, where the cognate nominal form occurs in the description of the foundation of Paul’s apostolic mission: “the will of God” (θελήματος θεοῦ). This emphasis on God’s active will again highlights the significance of his plan throughout history. Here Paul stresses that the inclusion of the Gentiles into God’s elect ones is not a historical accident; instead, it is within the predetermined plan of a God who is actively working in history. Some versions have chosen to make this idea explicit by translating the clause “God desired” as “it was God’s purpose” (NJB). This entire verse, with its references to the sovereign will of God, the glorious richness of the mystery, and the centrality of Christ, is similar to Eph 1:4–7.

“To make known” (γνωρίσαι) is another word often used in relation to the revelation of God’s mystery. The object clause after this infinitive is in indirect discourse and is introduced by an interrogative pronoun (τί), variously translated as “what” (KJV, ASV, NASB, REB), “what sort of,”44 and “how great” (NRSV, ESV) in this context. Although this pronoun can accentuate the quality or quantity of that which it introduces,45 here it functions primarily as an object marker (cf. 1 Thess 1:8; 1 John 3:2) and can therefore be omitted in translation.46

“The glorious riches” (τὸ πλοῦτος τῆς δόξης) literally reads “the riches of the glory.” In light of v. 11, where “the glory” is to be taken as a qualitative genitive, the genitive here takes on an adjectival sense, thus “the riches of his glorious inheritance” (CEV, TEV, TNIV, NET).47 The “riches” refers to the amazing plan of God that includes both Jews and Gentiles; Paul goes on to note explicitly that the object of God’s act of revelation is “the Gentiles.” In Eph 1:18, where one also finds the use of the phrase “the glorious riches,” Paul makes it clear that he has the “inheritance in his holy people” in mind—that is, the sharing of the inheritance among the Jews and Gentiles, both of which are now to be considered as God’s chosen ones.

1:27c-d Which is Christ in you, the hope of glory (ὅ ἐστιν Χριστὸς ἐν ὑμῖν, ἡ ἐλπὶς τῆς δόξης). While the previous relative clause identifies the recipients of the revelation of the mystery, this relative clause explains the content of such mystery. Grammatically, the relative pronoun “which” (ὅ) can refer either to “the … riches” or “this mystery” in the preceding clause. In light of 2:2 (“the mystery of God, Christ”), however, it is best to take “the mystery” as the antecedent of this pronoun. This relative clause explains the content of the mystery and explicitly identifies it with the indwelling of “Christ.” Taking “in you” (ἐν ὑμῖν) as referring to the Gentiles,48 Lightfoot is probably correct in claiming that “not Christ, but Christ given freely to the Gentiles is the ‘mystery’ of which St Paul speaks.”49

“The hope of glory” stands in apposition to Christ, who is the basis of this eschatological hope (cf. v. 23; 1 Tim 1:1). The genitive “of glory” (τῆς δόξης) is best taken as an objective genitive, thus, “the hope for glory” (NAB).50 This hope is “the blessed hope—the appearing of the glory of our great God and Savior, Jesus Christ” (Titus 2:13). In Jewish traditions, “glory” often accompanied the Torah, and the full “glory” will be restored at the end of time to those who are faithful to the law (2 Esd 7:95, 97; 1 En. 38:4; 50:1).51 To identify Christ as “the hope of glory” may then highlight his role as the fulfillment of the Torah, an assumption that lies behind the claim that in Christ, the mystery of God, one finds “all the treasures of wisdom and knowledge” (Col 2:3).

1:28a Him we proclaim (ὃν ἡμεῖς καταγγέλλομεν). “Him” translates the relative pronoun (ὅν) that points back to “Christ” (v. 27) as the center of Paul’s proclamation. This clause is important in providing critical corrections to possible misconceptions concerning the focus of this section. First, the self-description of Paul’s own suffering (vv. 24, 29) may give the impression that he is emphasizing his own role as the apostle. While his unique role is not to be doubted, Paul here emphasizes that it is “Christ” who is the object of all proclamation. With this relative pronoun, the reader is reminded not only of the grammatical antecedent in the previous verse, but all the previous mentions of “Christ” as the center and sole focus of Paul’s gospel (cf. vv. 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 15–20, 24). The role of Paul is a derivative one, and his status is relative to the absolute claim of Christ and his gospel that cannot be compromised.

Second, the appearance of the first person plural pronoun “we” (ἡμεῖς) is surprising, especially in light of the use of first person singular verbs before and after this verse (cf. vv. 24, 25, 29). Reading in light of first person plural verbs in v. 3, many assume that Paul is primarily referring to his specific coworkers (see vv. 1, 7–8; cf. 4:12–13),52 while others entertain the possibility of Paul’s use of the “editorial we” in this context.53 But both readings fail to explain the sudden appearance of this plural pronoun. It is more likely that Paul is intentionally including all who participate in the proclamation of the gospel message with this pronoun, and this group cannot be limited to those noted in this letter. The awkward repeated emphasis on “everyone” in the subordinate clauses that follow together with the note on “all wisdom” confirms that Paul is making a universal claim. This is also consistent with the reference to “the Gentiles” in the v. 27, a group not limited to the Colossians. This universal claim thus reminds one of early Christian confessions where the universal and absolute claim of the gospel is made (Rom 6:4; 1 Cor 8:6; 2 Cor 4:13–14; 2 Tim 1:9–10; Titus 3:4–7; cf. 1 Cor 1:23). In using this pronoun, Paul is situating himself within all those who confess Jesus to be the Christ.

The verb “we proclaim” (καταγγέλλομεν) belongs to missionary discourse, and the object of such proclamation is often “Jesus” (Acts 17:3), “Christ” (Phil 1:17–18), “the gospel” (1 Cor 9:14), or “the word of God/the Lord” (Acts 13:5; 15:36). As such, its uses overlap with that of “to proclaim” (κηρύσσω; cf. v. 23) and “to evangelize” (εὐαγγελίζω).54 This note on proclamation points to the concrete ways in which “the mystery” is able to be “revealed to his saints” (v. 26). Though those who proclaim are not the objects of such proclamation, they all play a critical role in fulfilling God’s plan in the historical plane.

1:28b-d Admonishing everyone and teaching everyone with all wisdom (νουθετοῦντες πάντα ἄνθρωπον καὶ διδάσκοντες πάντα ἄνθρωπον ἐν πάσῃ σοφίᾳ). Paul further identifies the means of proclamation in the acts of admonishing and teaching. These two adverbial participles can be taken either in an instrumental sense (“by admonishing … and by teaching”)55 or as participles of accompanying circumstances (“as we admonish … and teach”).56 It is unclear, however, whether such a distinction is a meaningful one here. Moreover, in light of the use of the verbs “to proclaim” and “to teach” as parallel terms in Acts 4:2, a fine distinction between “proclaiming,” “admonishing,” and “teaching” should not be made especially in reference to the early Christian missionary activity.57

“Admonishing” (νουθετοῦντες) may imply that an error needs to be corrected. In the NT, however, this word can also refer to the general instruction and proclamation of the word. In Rom 15:14, for example, the word denotes mutual encouragement: “I myself am convinced, my brothers and sisters, that you yourselves are full of goodness, filled with knowledge and competent to instruct [νουθετεῖν] one another.” Some have therefore preferred the rendering, “to lay at one’s heart”58—a rendering supported by 3:16. If so, “teaching” (διδάσκοντες) may denote an activity that need not be distinguished from “admonishing,” both of which are intimately related to the act of proclamation. In 2:6–7, being taught is equated to receiving the traditions concerning Jesus Christ.

In this context, Paul uses “admonishing” and “teaching” perhaps not to elaborate on the act of proclamation but to highlight the subsequent phrase “with all wisdom,” which illustrates its content.59 This phrase recalls “in all spiritual wisdom and understanding” of v. 9. The connection between v. 9 and this context is important. In the prayer report of v. 9 Paul points to God being the one who is able to fill the Colossians “with the knowledge of his will in all spiritual wisdom and understanding.” In this verse, however, Paul and the other gospel messengers become the agents through whom the recipients can receive “all wisdom.” This points to the emphasis on both divine acts and human mediation in this letter. In 2:2–3 Paul will again emphasize that this “wisdom” is hidden in Christ himself. This emphasis on “wisdom” anticipates Paul’s critique of the false teachers, who only acquire “an appearance of wisdom” (2:23).

In comparing 1:9 with this verse, another point becomes apparent. In the section where v. 9 belongs (vv. 3–14), Paul focuses on the particular situation of the Colossians and their faithfulness to God; in this context, however, Paul focuses on the power of the gospel among the Gentiles and uses the Greek term “all” (πᾶς) three times: “admonishing everyone [πάντα ἄνθρωπον],” “teaching everyone [πάντα ἄνθρωπον],” and “with all [πάσῃ] wisdom.” The reference to “everyone” (πάντα ἄνθρωπον) in v. 28e confirms this emphasis. Against the elitists, Paul is again emphasizing the universal scope and power of this gospel. In this verse, Paul points to both Jews and Gentiles as recipients of God’s work through Christ.

1:28e So that we may present everyone mature in Christ (ἵνα παραστήσωμεν πάντα ἄνθρωπον τέλειον ἐν Χριστῷ). This clause points to the purpose of the act of proclamation. As in v. 22, one again finds the use of the cultic term “to present” (παρίστημι), in reference to the proclamation of the power of Christ’s sacrificial death. While some translations chose to render τέλειον as “perfect” (KJV, ASV, NAB, NKJV, NJB, NLT),60 “(fully) mature” (RSV, NRSV, REB, ESV, TNIV, NET, NIV) is a more appropriate translation since Paul does not downplay the process of sanctification as he argues against those who claim perfection in their religious and ascetic practices (2:18, 23).

Nevertheless, this rendering should not deflect one from focusing on the finality of that which is required of believers as they stand before God. Paul emphasizes that this maturity is grounded in the unfolding of God’s will (Rom 12:2), which can be achieved only by the act of God in an eschatological era (1 Cor 13:10) when the believers find themselves in final and complete union with Christ (Eph 4:13). The “in Christ” (ἐν Χριστῷ) reference here is sufficient to highlight this salvation-historical, eschatological, and christocentric aspect in reference to Christian maturity. David Peterson is therefore correct in asserting that this maturity “is not some vague notion of ‘spiritual growth’ or ‘moral progress,’ but actualization of the redemption in Christ in personal and corporate Christian living.”61 In v. 22, Paul noted that Christ is to present believers as “holy, without blemish, and blameless before him”; this description helps us understand what is implied by the term “mature.”

1:29a For this I toil (εἰς ὃ καὶ κοπιῶ). With this clause, Paul returns to a discussion of his struggles for the sake of the gospel. The relative pronoun “this” (ὅ) is best taken to refer back to Paul’s attempt to “present everyone mature in Christ” (v. 28). Nevertheless, since such presentation is the goal of his act of proclaiming the gospel, Paul’s struggle ultimately points back to his wider apostolic mission. “For this” thus introduces the purpose for Paul’s toil, which can be made explicit in renderings such as “for this purpose” (NASB) and “to this end” (NKJV, REB, TNIV, NIV).

With “I toil,” Paul returns to his first person narration as he highlights his personal involvement in the spread of the gospel. Paul often uses this verb to describe his work for the Christian communities (1 Cor 15:10; Gal 4:11; Phil 2:16; cf. 1 Thess 2:9; 3:5; 2 Cor 6:5; 11:23). Although some consider this portrayal of Paul as authored by one of his admirers who was attempting to highlight his unique and exalted status,62 this reading is problematic. First, “since the verb and its cognate noun can both be used for common manual labor, the writer’s use of kopiaō suggests that he has not exalted Paul’s sufferings and work to the degree that they are in a completely different category from the suffering and work of other leaders.”63 Related to this is the fact that Paul himself often uses this term in his generally accepted letters to describe the labor of others (Rom 16:6, 12; 1 Thess 5:12). In highlighting his personal involvement, therefore, it is not his unique role that is emphasized here.

1:29b Striving with his energy that powerfully works in me (ἀγωνιζόμενος κατὰ τὴν ἐνέργειαν αὐτοῦ τὴν ἐνεργουμένην ἐν ἐμοὶ ἐν δυνάμει). Paul further qualifies his previous clause with a note on the source of his labor. The participle “striving” (ἀγωνιζόμενος) can indicate manner (“I toil strenuously,” REB; cf. TNIV, NIV) or attendant circumstances (“I labor, striving”).64 This verb may have belonged to the athletic imageries from which Paul often draws (cf. 1 Cor 9:25; 2 Tim 4:7),65 and it highlights a sustained effort for a particular goal. In this context, however, we cannot make a clear distinction between the previously noted toiling and the striving here. Some translations have therefore rendered the two as parallels terms, “I toil and struggle” (NRSV; cf. NAB; NLT; cf. 1 Tim 4:10).

The use of a participle (“striving”) that shares its semantic range with the verb it modifies (“I toil”) indicates that Paul is not introducing a new act; instead, he is attempting to explain the power that lies behind his toiling. This emphasis on being empowered by God’s power provides a critical balance to his earlier claim concerning his own work and labor. “His energy [ἐνέργειαν] that … works [ἐνεργουμένην]” reflects the Semitic use of a verb and its cognate noun.66 In Paul, ἐνέργεια often points to the power of God (Eph 1:19; 3:7; Phil 3:21; Col 2:12; 2 Thess 2:11), and it is often found together with other words denoting “power” (κράτος, Eph 1:19; ἰσχύς, Eph 1:19; δύναμις, Eph 3:7; 2 Thess 2:9; δύναμαι, Phil 3:21). The presence of “powerfully” (ἐν δυνάμει; lit., “with/in power”) is therefore not unusual.

Equally important is the connection between “energy” and the theologically significant term “grace,” especially illustrated in Eph 3:7: “I became a servant of this gospel by the gift of God’s grace given me through the working [ἐνέργεια] of his power.” For Paul and other NT authors, “grace” is a manifestation of the working and power of God.67 On God’s working through Paul’s own toil, a paraphrase of our present clause can also be found in 1 Cor 15:10: “I worked [ἐκοπίασα] harder than all of them—yet not I, but the grace of God that was with me.” Paul never allows the readers to consider him as the center of God’s work in history.

2:1a-b For I desire you to know how great a struggle I have for you (Θέλω γὰρ ὑμᾶς εἰδέναι ἡλίκον ἀγῶνα ἔχω ὑπὲρ ὑμῶν). While the previous subsection (1:24–29) provides a general statement on Paul’s stewardship of the gospel, this subsection (2:1–5) centers on Paul’s specific labor for the Colossians and Laodiceans. The previous subsection opened with the direct address to the audience through a second person plural personal pronoun “you” (vv. 24–25), and this pronoun was defined by the subsequent references to “the church” (vv. 24, 25), the “saints” (v. 26), “the Gentiles” (v. 27), and “everyone” (v. 28). In this subsection, however, the reference to “you” (ὑμῶν) is followed by specific references to the local audiences. This allows Paul to speak about his own absence from their midst (v. 5)—hence the need for this letter. More importantly, this shift from the general statement to the specific context situates the audience within the wider salvation-historical plan of God as they become the beneficiaries of God’s work through his Son.

“I desire you to know” highlights the significance of what follows (cf. 1 Cor 11:3).68 In terms of function, this is comparable to the formula “you know that” (3:24; 4:1), where Paul reminds his audience of what is important.69

“How great a struggle I have for you” indicates the intensity of the struggle Paul has endured. In English, “how great a struggle” could be rendered “I struggle very much indeed.”70 “A struggle” (ἀγῶνα) relates back to participle in v. 29 (“striving,” ἀγωνιζόμενος); although Paul did not make it clear as to the kind of “struggle” he had undergone for the sake of the readers, the connection with v. 29 provides some hints. In vv. 27–29, Paul connects his “striving” with his mission as an apostle to the Gentiles who is faithful in proclaiming the gospel message. In light of 4:3, where Paul states that he is “bound” in chains because of the proclamation of “the mystery of Christ,” the “struggle” should therefore include his imprisonment, which is a direct consequence of his faithfulness to his call and mission.71 In the verses that follow, Paul likewise points to his proclamation (vv. 2–3) and alludes to his absence, presumably a result of his imprisonment (v. 5). If we read 2:1–5 in light of 1:24, Paul’s “struggle … for you” is also to be understood in light of his participation in the eschatological suffering. This helps explain how he is able to suffer on behalf of those whom he had never met.

2:1c-d And those in Laodicea and those who have not seen my face in the flesh (καὶ τῶν ἐν Λαοδικείᾳ καὶ ὅσοι οὐχ ἑόρακαν τὸ πρόσωπόν μου ἐν σαρκί). Assuming that “for you” in the previous phrase refers to the Colossians, Paul points to other groups who have benefited from his ministry of proclamation. Laodicea was located eleven miles northwest of Colossae. The Jewish population in Laodicea can probably be traced back to third century BC when 2,000 Jewish families were settled in Asia Minor under the policy of Antiochus III. The significant contribution of the Laodicean Jews to the temple tax was documented before the first Jewish revolt.72 Students of the NT have often considered the message to the Laodiceans in Rev 3:14–22 as providing critical information concerning the first-century city of Laodicea, especially in the area of water supply (cf. Rev 3:15–16), finances (cf. 3:17–18a), textile industry (cf. 3:18b), and medicine (3:18c). More recent examination of the archaeological and textual data suggests, however, that these phrases evoke images understandable for the entire local region.73

Together with Hierapolis, Laodicea and Colossae are the notable cites in the Lycus Valley, and they are mentioned together in 4:13. It is unclear why Hierapolis is not also mentioned here,74 but it is possible that Laodicea is mentioned because the Laodiceans also received a letter from Paul, one that Paul encourages to be read aloud to the Colossians as well (4:16). Another possibility is that the Laodiceans are facing the same false teachings that plague the Colossians.75 Paul’s letters to the Colossians would then be of particular significance to the Laodiceans.

“And those who have not seen my face in the flesh” can refer to all those in Colossae and Laodicea who had not met Paul personally. If so, “and” (καί) is to be taken in an epexegetical sense. While some consider this phrase as referring to those whom he has not met, thus “universaliz[ing] Paul’s place in the church,”76 the shift from the universal language of 1:24–29 to the local references in 2:1–5 suggests that this group is likely referring to those who resided in the Lycus Valley.77 Paul’s discussion of his absence from them in v. 5 lends further support to this local reading.

2:2a-b So that their hearts may be comforted as they are united in love (ἵνα παρακληθῶσιν αἱ καρδίαι αὐτῶν, συμβιβασθέντες ἐν ἀγάπῃ). With this clause, Paul points to the purpose of his struggles for the Colossians, Laodiceans, and the others in the Lycus Valley. The “heart” is to be considered as the center of one’s will and emotions. In this case, Paul is pointing to one’s inner self: he wants them to “be comforted.”

The verb “comforted” (παρακληθῶσιν) is often translated as “encouraged” (NASB, NAB, NKJV, NRSV, NLT, TNIV, ESV, NIV), but this translation may focus too heavily on the emotional state of a person and is therefore unable to convey the significance of this term in this context. The verb can also be translated “strengthened,”78 which would relate to Paul’s activity of reaffirming the gospel message in this letter. The connection between this verb and the act of instruction is further supported by 1 Cor 14:31: “For you can all prophesy in turn so that everyone may be instructed [μανθάνωσιν] and encouraged [παρακαλῶνται].”

Our translation, “comforted,” understood properly,79 points to yet another layer in the significance of this term in this context. In the LXX, this verb evokes the eschatological comfort that will come from God in the time of salvation (cf. Isa 40:1, 2, 11; 51:3).80 The “comfort” that Paul’s eschatological suffering (cf. 1:24, 2:1) brings about is not simply the emotional and intellectual support for his readers; rather, his suffering will bring about the comfort that comes from God himself. The passive voice of this verb (a “divine passive”) supports this reading, and the relationship between Paul’s suffering and the comfort that is to come through God’s salvific act is made clear in 2 Cor 1:6: “If we are distressed, it is for your comfort and salvation; if we are comforted, it is for your comfort.”

The question concerning the function of the participle “as they are united” (συμβιβασθέντες) in this context is related to the wider question concerning the relationships between the various pieces in this verse. Some have divided the verse into four clauses as the “fourfold purpose of the struggle” of Paul:81

that their hearts may be comforted

and they may be united in love,

also that they may gain the full wealth of assurance…

and that they may gain the knowledge of the mystery of God.

This parallel structure does not, however, reflect the construction of this verse. The first clause, introduced by a “marker to denote purpose” (ἵνα),82 should be understood as the main purpose clause of the paragraph. The participial clause that follows (“united in love”) is best taken as modifying the act of comforting.83 The final two units, introduced twice by another purpose marker (εἰς), are purpose phrases, but it is unclear if they are to be seen as parallel with the ἵνα clause. Some take these phrases as the result of being “united in love,”84 but the presence of καί before these two phrases separates them from the participle and is best taken as modifying the entire purpose clause as introduced by “comforted” (παρακληθῶσιν):85

that their hearts may be comforted

as they are united in love

to obtain all the wealth of full assurance … and

the knowledge….

“As they are united in love” (συμβιβασθέντες ἐν ἀγάπῃ) introduces the theme of unity in this letter. Although in Greek the word “united” could acquire the sense of “instructed” especially in the LXX (cf. Exod 4:12, 15; Isa 40:13, 14),86 the use of this term in Col 2:19 and Eph 4:16 suggests that it should be understood in the sense of “being united.”87 Arguing against individual and elitist spiritual practices (2:16–23), Paul points to the significance of the unity of God’s people as they experience his redemption. This unity is explicitly noted in 3:11, where traditional barriers can no longer define their identity. Here in 2:2, “in love” points to the means through which such unity can be achieved. After the affirmation of the unity of God’s people in 3:11, one likewise finds the focus on “love” as the “bond” for perfect unity (3:14).

2:2c To obtain all the wealth of full assurance of understanding (καὶ εἰς πᾶν πλοῦτος τῆς πληροφορίας τῆς συνέσεως). With this prepositional phrase, Paul points further to the purpose of the comfort that the Colossians (and others) would receive. In Greek, “all the wealth” (πᾶν πλοῦτος) is followed by two genitives, “of full assurance” and “of understanding.” Two notable options are (1) taking “of full assurance” as a genitive of source and “of understanding” as objective genitive: “the wealth that comes from the full assurance of understanding” (NASB); and (2) taking “of full assurance” as a genitive of content and “of understanding” as genitive of source: “the wealth consisting of full assurance that springs from understanding.”88 What is clear is that Paul is providing an emphatic statement that highlights complete conviction and understanding as the purpose of one’s being comforted by the gospel message. The translation provided by NJB, though cumbersome, reflects Paul’s emphasis and passion here: “until they are rich in the assurance of their complete understanding.”

This purpose phrase provides a critical definition of the significance of the act of comfort. Instead of simply providing emotional support for his readers, Paul focuses on the need to have full conviction that is not to be separated from a complete understanding of the salvific plan of God. It is for their understanding of this gospel that Paul is willing to go through hardships and suffering.

2:2d-e And the knowledge of the mystery of God, Christ (εἰς ἐπίγνωσιν τοῦ μυστηρίου τοῦ θεοῦ, Χριστοῦ). Syntactically this purpose phrase, introduced by the same preposition (εἰς), parallels the previous phrase, but in terms of function this phrase further explains the content of the “understanding” noted in the previous clause. The connection between “knowledge” (ἐπίγνωσιν) and “understanding” (τῆς συνέσεως) has already been made in Paul’s prayer report (1:9), where he also considers the readers’ growth “in the knowledge of God” (1:10) as the goal of his prayer. This focus on “knowledge” continues in Paul’s ethical exhortation below (3:10). In this context, Paul’s discussion of this “knowledge” is explicitly linked with “the mystery of God”—a theme introduced in 1:26–27.

In the textual tradition, more than ten possible readings can be identified after “the mystery” (τοῦ μυστηρίου).89 The reading accepted by most translations, “of God, Christ” (τοῦ θεοῦ, Χριστοῦ), is supported by two of the best manuscripts90 and best explains the origin of the other variants.91 The genitive “of the mystery” is an objective genitive that functions as the object of the verbal noun, “knowledge.” “Of God” can also be taken as an objective genitive (“[mystery] about God”), but it is best taken as a possessive genitive in light of a similar construction in 1:9. Finally, “Christ” has often been taken as a genitive of apposition that defines “mystery” (“mystery, that is, Christ,” NRSV; cf. NASB, REB, NLT, ESV).92 This reading is supported by the early connection between “Christ” and “mystery” (1:27). Since “the mystery of God” can be identified with the gospel that centers on Christ,93 to know the mystery of God is to know Christ.

2:3 In whom all the treasures of wisdom and knowledge are hidden (ἐν ᾧ εἰσιν πάντες οἱ θησαυροὶ τῆς σοφίας καὶ γνώσεως ἀπόκρυφοι). With the relative pronoun “whom” (ᾧ) referring to Christ (v. 2), this prepositional phrase provides further description of the significance of Christ. The construction points back to the prepositional Christology of the christological hymn, where two references to “in him” (ἐν αὐτῷ, 1:16, 19) bracket the climactic and central affirmation: “in him [ἐν αὐτῷ] all things are held together” (1:17). Just as the hymnic affirmation points to the critical role of Christ, the present affirmation also points to his unique status. In light of the emphasis that “all [πάντες] the treasures of wisdom and knowledge” are contained in him, one is justified in rendering the phrase as “in him alone are hidden all the treasures of wisdom and knowledge.”94

“The treasures” (οἱ θησαυροί) denote “that which is stored up.”95 The two genitives that follow (“of wisdom and knowledge,” τῆς σοφίας καὶ γνώσεως) should be considered as genitives of content, thus providing the description of “all the treasures.” The focus here is on “all,” which stresses that the readers possess such richness and thus have no need to seek that which is only an illusion of such wisdom and knowledge (cf. 2:4, 23).96

“The treasures” rarely appears in the Pauline corpus,97 although the pair “wisdom and knowledge” does appear elsewhere (Rom 11:33; 1 Cor 12:8; cf. Eph 1:17; Col 1:9). All three word groups, however, appear in the same context in the LXX. Many have pointed to the significance of Prov 2:1–8, where one finds the following claim: “For the LORD gives wisdom [σοφίαν]; from his mouth come knowledge [γνῶσις] and understanding. He holds success in store [θησαυρίζει] for the upright” (Prov 2:6–7a).98 Most scholars affirm the influence of wisdom traditions in both canonical (Dan 2:19–22)99 and extracanonical material (Sir 1:24–25; Wis 6:22; 7:13–14; Bar 3:15).100 Paul is clearly portraying Christ as the embodiment of wisdom, and through Christ and him alone can one understand the divine will and plan.101

The notion of hiddenness (ἀπόκρυφοι) provides yet another dimension of Paul’s description of Christ as the embodiment of wisdom. In 1:26–27, Paul speaks of the revelation of the mystery to “the saints,” but the public revelation remains in the future, when these saints will appear with him in glory (3:4).102 This hiddenness does not point to the need for further revelation for those in Christ precisely because these saints are already “hidden with Christ in God” (3:3). Paul’s focus on hiddenness in this context points rather to the significance of the unfolding of the salvation plan of God. The mere use of the term “hidden,” therefore, anticipates the point of full and complete revelation.103

2:4 I say this so that no one may deceive you through speculative arguments (τοῦτο λέγω ἵνα μηδεὶς ὑμᾶς παραλογίζηται ἐν πιθανολογίᾳ). Here Paul shifts from the unique status of Christ, whom he preaches, to the deceptiveness of the false teachers whom the Colossians may be encountering. Some have therefore considered this verse as the beginning of a new section, with “this” (τοῦτο) pointing forward to the words that follow: “I tell you, then, do not let anyone deceive you …” (GNB).104 This reading is, however, problematic.

First, “I say this” in this concluding part recalls “I desire you to know” at the beginning of this paragraph (v. 1), as Paul expresses concerns for his readers. While vv. 1–3 focus on the positive note of encouragement, this verse points to the warning that must be issued. The reappearance of the direct address to the readers (“you,” ὑμᾶς) in this verse and in v. 1 provides coherence for this paragraph.

Second, while Paul can use “I say this” to refer to something that follows (cf. Gal 3:17; 1 Cor 1:12), with “so that” (ἵνα) the phrase should be understood to refer to what precedes:105 “My aim in telling you all this is that….”106 Paul is providing the rationale and a concluding note concerning what he just said. This statement highlights the urgency of Paul’s previous comments concerning the gospel he is commissioned to preach.

Behind the reference of “no one” (μηδείς) lies the false teachers whom Paul is criticizing (cf. v. 18), as are the references to “no one” and “anyone” in 2:8, 16. Some consider these references as indicating “that the philosophers were not a large group, but actually a minority from a numerical point of view.”107 It is equally possible, however, that Paul uses such references to downplay the significance of the false teachers rather than their number, by rhetorically stripping them of influence and identity.

The verb “deceive” (παραλογίζηται) should most likely be taken in the middle voice to refer to the act of deception through false reasoning (cf. “talks you into error,” REB).108 This definition is supported by papyri usages where the verb can be applied for the “wrong use” of particular documents.109 In this context, deception is carried out through the means of “speculative arguments” (πιθανολογίᾳ), a word not easily translated by an English word. In Classical Greek, this word is used in reference to speculative arguments as opposed to empirical demonstration.110 “Speculative arguments” is thus justifiably rendered as “fine-sounding arguments” (TNIV, NIV), “well-crafted arguments” (NLT), “specious arguments” (NAB, NJB, REB), or even “fancy talk” (CEV). In any case, this verse anticipates 2:8, where Paul likewise warns his audience of the misleading arguments posed by the unnamed false teachers, though he uses stronger and more explicit language: “See to it that no one takes you captive by means of empty and deceitful philosophy.”

2:5a For though I am absent in body, I am with you in spirit (εἰ γὰρ καὶ τῇ σαρκὶ ἄπειμι, ἀλλὰ τῷ πνεύματι σὺν ὑμῖν εἰμι). Paul’s unique role in the plan has already been established (1:24–29), and his work for the Colossians in particular (2:1–3) further establishes his position as one who has the authority to remind them of the gospel they have received. Now Paul deals directly with his absence and thus introduces the significance of this letter.

“For” (γάρ) provides the grounds for Paul’s issuing his warnings in v. 4, and they will find fuller development in what follows. Some have taken this sentence as pointing to the very danger caused by Paul’s absence: “the danger at hand is not to be underestimated, because the Apostle is distant and cannot be on hand to speak directly to the community.”111 “For” thus points to the reason for Paul’s urgent words of warning. While the reality and the potential peril of Paul’s absence cannot be denied, Paul’s focus here is not the severity of the situation but his unique authority as an apostle.

“Absent in body” can literally be rendered as “absent in the flesh” (KJV, ASV, NKJV); in light of this context it is clear that Paul is simply referring to his physical presence. His choice of the word “flesh” (σάρξ) instead of “body” (σῶμα) here and in v. 1 may be due to the use of this pair at the beginning of this section (1:24). There Paul uses the term “flesh” in reference to his own body, but he reserves the term “body” for the church, the “body” of Christ. Elsewhere in a similar context, Paul uses the word “body” instead: “For though I am absent in body [τῷ σώματι], I am present in spirit” (lit. trans. of 1 Cor 5:3; cf. 2 Cor 10:10). Elsewhere Paul could also talk about his absence “in face” (προσώπῳ, 1 Thess 2:17; cf. also Col 2:1). In any case, the flexibility of Paul’s use of these related terms is to be recognized.112

Some have, however, suggested that “I am with you in spirit” refers not to Paul’s spirit/heart but to the Holy Spirit, who is present with the readers as they read Paul’s own written words.113 In light of Paul’s reference to his physical presence, however, this phrase seems primarily to refer to Paul’s own self, though one cannot deny that “this self is connected with the divine Spirit which grants strength to the apostle to unite with the community in common action, despite the distance.”114 Moreover, consistent with the epistolary practices of his time, Paul’s use of the absence-presence formula also sheds light on this verse.115 His physical absence provides the urgent necessity for writing this letter. His words thus represent the very words of Paul the apostle, and in this manner he is present among them “in spirit.”

2:5b Rejoicing to see your order and the firmness of your faith in Christ (χαίρων καὶ βλέπων ὑμῶν τὴν τάξιν καὶ τὸ στερέωμα τῆς εἰς Χριστὸν πίστεως ὑμῶν). With this description of his expectation of the Colossian believers, Paul concludes this section before addressing directly the false teachings that those believers face. In Greek, “rejoicing to see” consists of two participles connected with a conjunction, rendered literally by the KJV as “joying and beholding.” In this context, it is best to consider the two participles as expressing one complex verbal act,116 and this is adopted by almost all modern English translations: “rejoicing to see.”

“Order” (τάξιν) and “firmness” (στερέωμα) could evoke a military context: “your orderly formation and the firm front which your faith in Christ presents.”117 But in Paul, “order” has only appeared elsewhere in 1 Cor 14:40 in reference to proper and orderly behavior.118 “Firmness” only appears here in the NT, but related forms have been used in the description of the strengthening (Acts 16:5; cf. 3:7, 16) and firmness (1 Pet 5:9; cf. 2 Tim 2:19) of one’s faith.119 While “of your faith” (πίστεως ὑμῶν) can conceivably modify both “order” and “firmness,” in light of the first appearance of the same personal pronoun (“your”) earlier in the clause, it is best to take that first ὑμῶν as modifying “order,” and “of your faith” as modifying “firmness.” Taking the conjunction “and” (καί) as having an epexegetical function, the interrelationship between the two parts of the sentence becomes clear: “rejoicing to see your order that is reflected in the firmness of your faith in Christ.” In this context, the focus is not simply on their order or the strength of their faith; it is on the anchor of their lives “in Christ,” which points to Christ as the object of their faith.

Paul’s note of joy and praise has several possible functions here. First, these words of praise have been considered a rhetorical device through which the goodwill of the audience is secured.120 Second, the note of “rejoicing” points back to the beginning of this section, where the same verb (χαίρω) appears in reference to Paul’s rejoicing over his own sufferings for the sake of the Colossians (1:24). This second note provides closure for this section while providing transition to the next section, which focuses intently on the strength of the faith of the Colossians. Third, and perhaps most importantly, the reference to “in Christ” paves the way for his arguments where he reaffirms the centrality of Christ in the faith of the believers. In combating the false teachings that the Colossians are facing, Paul insists that nothing less than a christocentric faith is sufficient for one to stand firm in the gospel they have received. It is for this gospel, after all, that Paul is willing to undergo great sufferings and afflictions.

Theology in Application

Identity and Self-Understanding

It may surprise some that we begin a section that deals with eschatology, gospel, mystery, wisdom, and apostolic suffering with a section on one’s self-understanding. Within the structure of Colossians, however, this section that focuses on Paul’s identity and mission does have a special role. After the discussion of the work and significance of Christ (1:15–23), and before dealing directly with the issues the Colossians are facing (2:6–23), one finds the critical bridge in the self-portrayal of Paul the apostle. While it can be dangerous to pull this aspect out of its theological and rhetorical contexts, certain elements of what Paul affirms here are relevant for all believers who seek to find their identity properly grounded in the gospel they have received.

Paul’s autobiographical details begin with the account of his call from God to become one who serves the word of God (1:25). In response to this call, Paul commits himself to proclaiming that word to all people as he is empowered by God (1:29). What is missing in Paul’s self-portrayal here is worth noting. Paul does not comment on his educational background in both Jewish and Greco-Roman centers of learning,121 nor does he emphasize his experience as a teacher of the Torah and one who must have had considerable power within the Jewish religious and political system.122 He focuses solely on his call from God, the source of his power. This is ultimately grounded in his understanding of the powerful grace of God, which is able to transfer sinners despite their unworthiness.

One noteworthy element in this self-portrayal is the importance of the “mystery” of God, which is revealed now at the end of times when God works through Christ in this climax of salvation history (1:26). Paul not only grounds his mission within this significant unfolding of salvation history, but his mission is also to be the instrument through which such “mystery” can be revealed to those who encounter the gospel (2:2). Throughout this self-portrayal, therefore, Paul identifies his life and ministry within the wider salvation plan of God. Writing in prison as he looks back at his ministry, Paul finds meaning neither in his accomplishments nor in the exotic episodes in his numerous journeys,123 but in his participation in the unfolding of God’s purpose. This purpose centers on “Christ,” who is, after all, “the mystery of God” (2:2). Before encouraging his readers to lead a Christ-centered life, he first demonstrates what such a life looks like.

In our contemporary culture, where greatness is often defined by one’s popularity, income, or social and political status, this section serves as a powerful reminder for the church to create a different culture, where significance is to be measured in a radically different way. In the early church, one can point to numerous “minor characters,” such as Matthias (Acts 1) and Ananias (Acts 9), who must be considered as “great” since they accomplish their call within the redemptive history of God. For us, our identity and worth are to be measured by our faithfulness to God’s wider plan of redemption and our specific calls within that plan.

Struggles and Afflictions

Both Paul’s focus on the call of God, who empowers him, and his role as the proclaimer of the gospel within the wider plan of God are grounded in his understanding of God’s grace, which does not allow for any boasting: “For when I preach the gospel, I cannot boast, since I am compelled to preach” (1 Cor 9:16). The achievement in which Paul does boast, however, is his own struggles: “If I must boast, I will boast of the things show my weaknesses” (2 Cor 11:30; cf. 12:9). It is not surprising, therefore, to find Paul discussing his own struggles and sufferings whenever he talks about his own identity and mission.

In his discussion of his suffering here, it is important to note that Paul does not provide a general theology of suffering, nor does he exhaust all types of suffering a believer may encounter. Rather, Paul’s focus is on his own suffering in the ministry of the gospel. To recognize this does not limit the power of this discussion, however, as it points to several important elements that are relevant for those who suffer for the sake of the gospel. First, to suffer for the sake of Christ is at the center of his mission as an apostle. The reference to “the commission from God given to me for you” (1:25) clearly points to the relationship between suffering and the ministry of “the word of God” (1:25). This is consistent with the Lukan account of Paul’s call and conversion in Acts 9:16 through the words of the risen Lord: “He must [δεῖ] suffer for my name.”

This reference to divine necessity points to the relationship between Paul’s suffering and Christ’s own suffering. In Luke 9:22, for example, one finds the same term for Jesus’ prediction concerning his own death: “The Son of Man must suffer [δεῖ] many things and be rejected … and he must be killed.” Regardless of how the expression “the afflictions of Christ” (Col 1:24) is to be understood, the numerous references to Christ in this section (cf. 1:27, 28; 2:2, 5) point to the relationship between Paul’s suffering and Christ’s own death, which was the center of the previous section (1:18, 20, 22).124 To be an apostle of Christ means, therefore, that one must be willing to “take up their cross” and follow him (Luke 9:23). In focusing on a lifelong ministry of walking on the path of the cross, Paul provides an alternative to those who are involved in ascetic practices (2:20–23) without fully realizing the demands of the cross that involve a total reorientation of one’s life in response to what was accomplished on the cross.

The reference to divine necessity also points to the wider plan of God within which the suffering of both Jesus and Paul has to be understood.125 Paul identifies his suffering with the revelation of Christ as “the mystery hidden for ages and generations” (1:26). This suffering is not an end in and of itself, but it points forward to Christ, who is also identified as “the hope of glory” (v. 27). For Paul, therefore, to align his suffering with Christ is to experience living in light of the climax of salvation history, which centers on the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ with the hope for the fulfillment of such history in the full revelation of Christ’s glory.

This is consistent with Paul’s affirmation elsewhere that “we share in his [Christ’s] sufferings in order that we may also share in his glory” (Rom 8:17), and that “our present sufferings are not worth comparing with the glory that will be revealed in us” at the end of times (8:18). Within such a wider perspective, suffering in Christ’s name is to experience fully the tension between the “already” and the “not yet.” Perhaps Paul emphasizes his own suffering at this point to reintroduce this temporal perspective into a community that seeks to transcend this tension in achieving the experience of the consummated age.

Finally, Paul does not suffer for suffering’s sake. Instead, he considers his suffering as contributing to the body of Christ. Paul begins by noting that his suffering is “for your sake” and “for the sake of his body, which is the church” (1:24). Turning his attention to his immediate readers, Paul again emphasizes “how great a struggle” he has for them (2:1). In light of the emphasis on the efficacy and sufficiency of Christ’s death in 1:15–20, Paul’s notes on his suffering for the church aim not at exalting himself as the great benefactor of the church. Instead of reaffirming a martyr mentality, Paul is emphasizing his solidarity with those who are also looking forward to the fulfillment of “the hope of glory” (1:27). It is not surprising, therefore, to find his statement that his suffering is to build up the community of God’s people “in love” (2:2). Transforming an individualistic view of spirituality, Paul points to the community through which the mystery of God can be fully made manifest. Suffering, then, becomes the means through which community can be built as God’s people share in the weaknesses that create the space of the powerful acts of God.

Suffering and persecution are very much a reality for believers in many parts of the world. Paul reminds these believers that their suffering is not in vain and that it often serves to build up the churches. It may perhaps seem surprising to believers in other parts of the world when these suffering brothers and sisters are not always envious of the life of the churches in the “free” world since they fully understand the sanctifying power of suffering in creating an alert community that thirsts for the final consummation of God’s kingdom. In a meeting with pastors of underground churches in a “closed” society, I was struck by the response they gave when asked of the greatest worries they have for their churches: “the end of the persecution of our churches.” Their response reflects a realization that the lack of suffering and affliction can often lead to a lazy church that is no longer alert in her existence between the times. For those in the “free” world, we are called to be alert as faithful witnesses in our own contexts. We are also called to identify with the suffering believers through prayer, financial support, and short-term and long-term mission work.