Chapter 7

Colossians 3:1–11

Literary Context

Many consider 3:1–4 as signifying the shift from the theoretical to the practical.1 This reading is correct in noting the shift in focus from the polemic to the hortatory as Paul encourages his audience to “set your minds on the things above, not things on the earth” (v. 2). The paragraphs that follow, which include vice (vv. 5, 8–9) and virtue (vv. 12–14) lists, a call to lead a life of worship (vv. 15–17), and a discussion of behavior within the household (3:18–4:1), confirm this reading.

It is incorrect, however, to consider 2:23 as the conclusion of Paul’s theoretical arguments or that Paul does not have the false teachers in mind in the remaining sections. First, the connection with the previous section is unmistakable. Paul’s discussion of the believers’ participation in the death of Christ, introduced by a conditional clause in 2:20, finds its counterpart in 3:1, which likewise begins with a conditional clause as he discusses the significance of their participation in Christ’s resurrection (3:1).2 Putting to death evil desires in v. 5 also points to the continued relevance of the arguments presented in 2:20–23.

Second, this section begins with a call to “seek the things above” (3:1). This is not an abstract call to follow Christ; rather, it comes after the extensive polemic against the false teachers, who apparently were promoting the “worship of angels” (2:18) and related cultic practices (2:20–21, 23). Paul here challenges such visionary experiences. Instead of seeking what is exotic and alien in the realm “above,” Paul specifies that the one who should be worshiped is “Christ,” who is “seated at the right hand of God” (3:1). The call to “seek the things above” and the expansion of this call in 3:5–11 are thus a polemical note against those who seek private visions in an attempt to obtain superior religious experiences.3

Third, the introduction of a note on eschatology in the appearance of Christ at the end of time (v. 4) also provides a strong response to the false teachers at Colossae. Instead of focusing on the present, private consummation of one’s communion with the divine, Paul emphasizes the coming public display of the glory of Christ, when every believer “will be revealed with him in glory” (v. 4). As in 2:20–23, therefore, this section should also be considered a transitional paragraph that combines theoretical discussions with Paul’s paraenetic concerns.

In 3:5–11, Paul moves further to the concerns of Christian living, though this section is also clearly built on the foundation of the previous sections. Concern for Christian living reflects the affirmation in 1:15–20, where the church, which symbolizes the new creation, is compared to the creation of the universe. As such, “the church becomes the microcosm for cosmic reconciliation.”4 The concern for the behavior of the believers is therefore a concern closely related to the discussion of Christ as the Lord of the cosmos.

The discussion that follows this section continues Paul’s concern to establish the right pattern of behavior for the Christian community. As 3:5–11 points to the stripping off of the old nature as one participates in the community of God’s people, 3:12–14 points to the putting on of the new nature. This leads to the reaffirmation of the lordship of Christ through thanksgiving (3:15–17), a theme concretely illustrated in Paul’s discussion of household relationships (3:18–4:1). Thus, Paul continues to explain the centrality of Christ as the necessary basis for one’s worship and moral life.

- V. Faithfulness of the Believers (2:6–4:1)

- A. Call to Faithfulness (2:6–7)

- B. Sufficiency in Christ (2:8–23)

- C. Reorientation of Christian Living (3:1–4:1)

- 1. Focus on the Risen Christ (3:1–4)

- 2. Take off the Old Humanity (3:5–11)

- 3. Put on the New Humanity (3:12–17)

- 4. Lord of the Household (3:18–4:1)

Main Idea

Believers should focus on Christ alone, the exalted one who will be revealed in glory at the end of times. Identified with this exalted Christ, believers are to live lives that are not controlled by the earthly desires, and they are to participate in a unified community that finds its foundation in nothing but Christ himself.

Translation

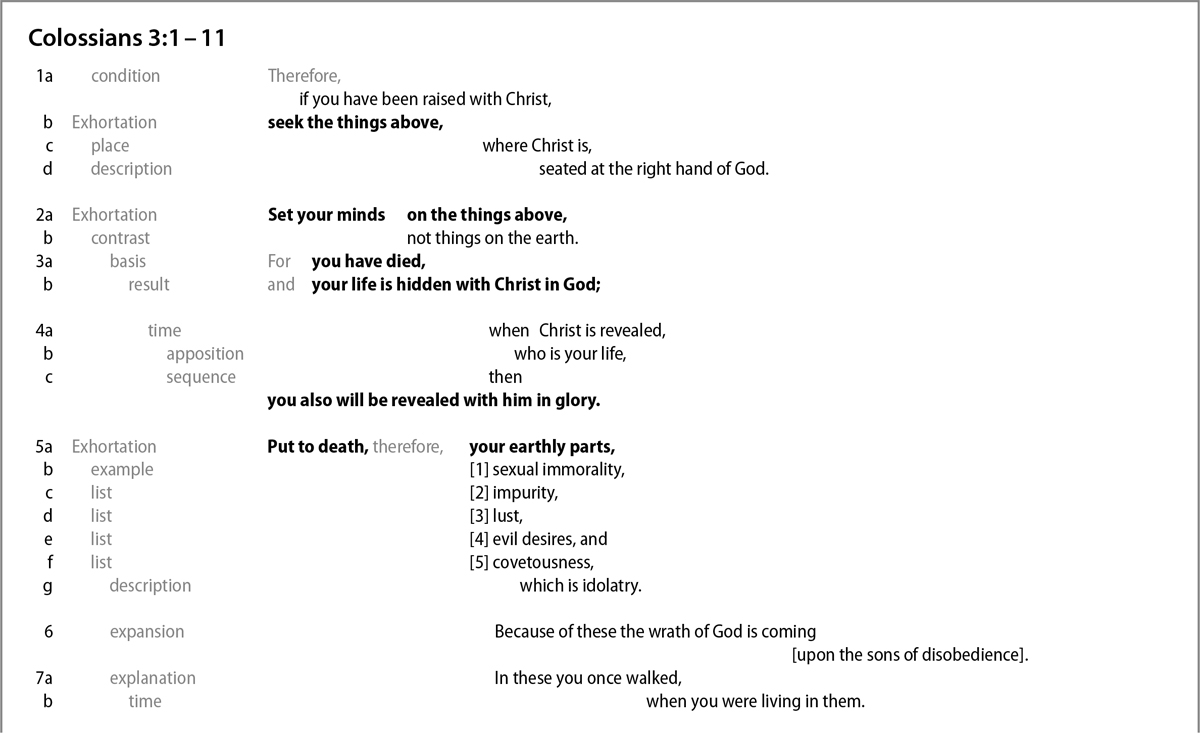

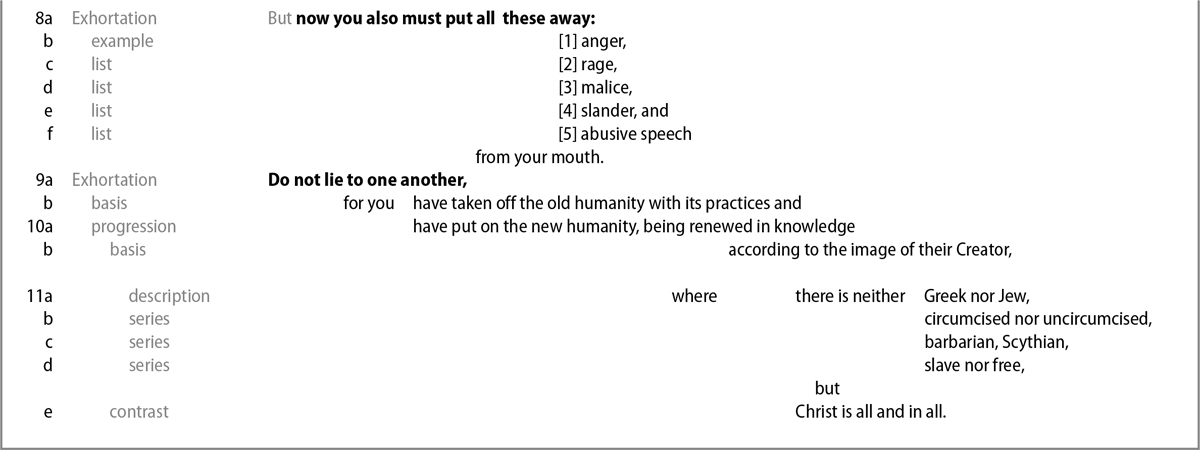

Structure

After a critique of the false teachers who were promoting the worship of heavenly beings (2:16–19), Paul reminds his readers that their proper object of worship is Christ, who is seated at the right hand of God (3:1–4). In this section, therefore, Paul returns to his intense focus on Christ as the only acceptable object of worship. Since believers have been raised with Christ, they are to “seek the things above” (v. 1). These “things above” are not lofty heavenly visions, however, but “Christ,” whose body exists in the earthly realm (cf. 3:5–4:1). To “seek the things above” is, therefore, to live a life worthy of Christ, who died on the cross and was raised from the dead (vv. 2–3a).

The present reality of sharing in Christ’s death and resurrection anticipates the glory to come (vv. 3b–4). Instead of the benefit for a few who are able to obtain superior knowledge in their private religious experiences, Paul emphasizes the full revelation of glory in the public return of Christ at the end of times. The eschatological consummation of salvation history that centers on the mighty acts of God through Christ becomes the foundation of Paul’s critique of those who focus on self-centered religious experiences.

In vv. 5–11, Paul illustrates the implications of the worship of the exalted Christ for believers struggling in their earthly existence. It is significant that Paul starts with their identity in the exalted Christ (vv. 1–4) and only then proceeds to their pattern of behavior (vv. 5–11). Unlike the false teachers, who insist on their own works as they attempt to participate in the heavenly experiences, “Paul moves in the reverse direction, since he sees the starting-point and source of the believer’s life in the resurrected Christ in heaven, from where it works itself out into the earthly life (3:5ff).”5

In the call to take off the old self, Paul begins with two vice lists that sandwich the grounds for rejecting such vices (vv. 5–8). The first vice list contains a catalogue of sinful desires (v. 5), several of which remind one of the Ten Commandments. The final explanatory phrase, “which is idolatry” (v. 5g), is important because it points to the central concern behind these vices. Paul is not simply randomly listing the vices that believers should avoid; he is rather describing selected manifestations of hearts that worship idols and is more concerned with the ultimate object of worship, Christ. Criticizing the false teachers of false worship, Paul points to a life that manifests the worship of the true God.

The grounds of Paul’s exhortation provided in vv. 6–7 further confirm this reading as he urges the (Gentile) believers to abandon a pattern of behavior that characterized their life before they participated in Christ’s death and resurrection. Consistent with his emphasis in vv. 1–5, Paul again points to the eschatological judgment as the reality that faces those who refuse to worship the one true God.

The second vice list contains a catalogue of sins related to speech and violent offenses in interpersonal relationships (v. 8). While the previous list in v. 5 may point to the sins of one’s heart, this list may point to those actions that interrupt the harmonious life of the community of God’s people. While the exhortation “do not lie to one another” (v. 9a) introduces the final paragraph of this section, it also serves as a concluding remark for this second vice list. Its function is comparable to the explanatory phrase in v. 5g (“which is idolatry”). In other words, the sins listed in v. 8 are actions of lying to one another. They point to a life in falsehood that refuses to acknowledge the truth and reality of the death and resurrection of Christ. This therefore corresponds to the sin of idolatry.

This reading of the vice list in v. 8 is confirmed by 3:9b–11. In 3:9b–10, Paul points directly to the putting on of the “new humanity” according to the image of its Creator. The notes on the new humanity bring up the issue of living according to one’s confession. In 3:11, Paul defines this “new humanity” in communal terms. Instead of focusing simply on individual virtues, Paul defines this “humanity” as a community that is not to be divided along ethnic, cultural, or social lines. This focus on community is also a response to the false teachers, who have erected barriers in their focus on private experiences for a few. Instead, Paul points to “Christ” (v. 11e) as the sole foundation of this community. The “new humanity” is the “body of Christ” (1:18, 24; 2:19; cf. 3:15), which reflects the power of God’s work in Christ’s death and resurrection.

Exegetical Outline

- I. Focus on the Risen Christ (3:1–4)

- A. Having been raised with him, seek things above (3:1)

- B. Having died with him, do not focus on the things below (3:2–3a)

- C. Having been hidden with him, you will be revealed in glory (3:3b–4)

- II. Take Off the Old Humanity (3:5–11)

- A. Put to death the earthly nature (3:5–8)

- 1. Catalogue of the sins of desire (3:5)

- 2. Warning to those who live in their past (3:6–7)

- 3. Catalogue of the sins of speech (3:8)

- B. Resist The Life In Falsehood (3:9–11)

- 1. Do not lie to one another (3:9a)

- 2. Because you have put on the new nature (3:9b–10)

- 3. New nature defined as the new community in Christ (3:11)

- A. Put to death the earthly nature (3:5–8)

Explanation of the Text

3:1a Therefore, if you have been raised with Christ (Εἰ οὖν συνηγέρθητε τῷ Χριστῷ). Paul reminds the Colossian believers of their new lives and identities in Christ. As in previous sections (cf. 2:6, 16), “therefore” (οὖν) marks the transition into another stage of Paul’s argument. In his discussion of baptism in 2:12, Paul has already noted how believers were raised in Christ. Closer to this section, the protasis of the conditional clause (“if you have been raised with Christ”) here naturally completes the thought of 2:20 (“if you have died with Christ”). In both clauses, the participation of the death and resurrection of Christ is not in doubt, and these notes serve rather as the grounds for Paul’s further argument concerning the appropriate behavior of the believers. As with 2:20, it is justifiable to translate this protasis as an assumed fact: “since … you have been raised with Christ” (NIV, TNIV).6

The passive verb “you have been raised” (συνηγέρθητε) points to God’s actions, which serves as a corrective to the false teachings that emphasize human efforts in approaching the divine. While the previous note on dying “with Christ” (σὺν Χριστῷ) uses the pronoun “with” (σύν) in emphasizing the believer’s identification with Christ, a similar effect is accomplished here with the prepositional prefix (“with,” σύν-) attached to the verb “to raise” (see comments on 2:12). To be raised “with Christ” is to be raised “to new life with Christ” (NLT). Although 2:12 pointed directly to baptism as the context of the believers’ participation in the resurrection of Christ, baptism is but “the symbolic center”7 of the believer’s participation in an entire new pattern of life that involves spiritual, mental, physical, and cultic aspects. In the discussion that follows, Paul makes clear what this new life in Christ entails.

3:1b-d Seek the things above, where Christ is, seated at the right hand of God (τὰ ἄνω ζητεῖτε, οὗ ὁ Χριστός ἐστιν ἐν δεξιᾷ τοῦ θεοῦ καθήμενος). In light of the believers’ sharing in the resurrection of Christ, they are called to “seek the things above.” With the definite article τά), the adverb “above” (ἄνω) takes on a substantive sense: “the things above.” Since this adverb is used substantivally only here (and in v. 2) in the NT, some scholars argue that “this is another of the catchwords of the philosophy.”8 If so, what is striking is not Paul’s call to “seek the things above,” but his further explication of that which is above. While the false teachers encourage their followers to focus on the heavenly realm (2:18), Paul makes it clear that the center of such heavenly attention is nothing but Christ himself.

“Where Christ is, seated at the right hand of God” can be taken in two ways, and each option depends on the relationship between the indicative verb “is” (ἐστιν) and the participle “seated” (καθήμενος). Some take both together as a periphrastic construction, expressing one verbal idea: “where Christ is seated at the right hand of God” (TNIV; cf. KJV, NAB, NLT, TEV). In light of the intervening prepositional phrase (“at the right hand of God”), which can modify either the auxiliary verb or the participle,9 it is more plausible that Paul is expressing two verbal ideas: “where Christ is, seated at the right hand of God” (NRSV, NIV; cf. ASV, NASB, NJB, NKJV, REB, NLT, NET, HCSB, ESV).

This separation of the two clauses also allows them to contain independent though related concepts. To identify Christ in heaven is to situate him where the throne of God is situated (see 2 Chr 18:18; Pss 11:4; 103:19; Isa 6:1; 66:1; Dan 7:9).10 This affirmation attests to the power and glory of one who has participated in God’s creative act (cf. 1:15–20), and this is consistent with the high Christology exhibited throughout the previous sections.

“Seated at the right hand of God” furthers this christological affirmation with an allusion to Ps 110:1 (109:1 LXX): “Sit at my right hand until I make your enemies a footstool for your feet.” The lack of exact parallel has caused some to question this allusion, but the widespread use of this psalm in early Christianity makes this connection more probable than not (Acts 2:34–35; Heb 1:13; 8:1; 10:12–13; 12:2; 1 Pet 3:22). Moreover, this allusion also fits the context of Paul’s arguments: since Christ has defeated all the spiritual powers and forces (2:10, 15; cf. 1:16), he alone should be worshiped. With the allusion to Ps 110:1, therefore, one finds affirmation of the beginning of Christ’s sovereign rule.11 The consummation of such rule is again dependent on Christ’s return in glory (cf. v. 4).

The participation of Christ in God’s glory is further illustrated by the metaphor of “seating.” In Jewish traditions, God alone sits in the heavens, while the other subordinating angelic beings stand beside him.12 Christ’s being seated at the right hand of God, therefore, points to his sharing of God’s sovereign rule. The allusion to Ps 110:1 is a striking departure from Jewish traditions, which find little use of this verse. This “difference simply reflects the fact that early Christians used the text to say something about Jesus which Second Temple Jewish literature is not interested in saying about anyone: that he participates in the unique divine sovereignty over all things.”13

The affirmation of Christ’s status and his participation in God’s sovereignty do not simply aim at responding to the false teachers. They also provide the foundation for a pattern of Christian earthly living that should reflect this heavenly reality. In the remaining sections, Paul draws out the practical implications that flow from the common Christian confession that “Jesus is Lord” (Rom 10:9; 1 Cor 12:3).

3:2a Set your minds on the things above (τὰ ἄνω φρονεῖτε). This clause completes the thought of “seek the things above” in v. 1. “Set your minds” goes beyond “seek” in emphasizing the need to dwell intently on the things above, and this translation is adopted by most modern versions.14 NLT’s more dramatic rendering may further bring out the nuance of this verb in this context: “Think about the things of heaven.” This involves the transformation of one’s mind in the obedient submission to God’s will as manifested in both thoughts and actions (cf. Rom 12:1–2).15

The significance of this verb is best illustrated by its uses in another of Paul’s prison letters, written most likely during the same period of time. In Philippians, after the call for believers to being “like-minded” (τὸ αὐτὸ φρονῆτε) since they have “one mind” (ἓν φρονοῦντες; Phil 2:2), Paul criticizes those whose “mind is set on earthly things” (οἱ τὰ ἐπίγεια φρονοῦντες, 3:19). Instead, believers’ “citizenship is in heaven” (3:20a).

This reminder of the heavenly orientation of the believers in Philippians is likewise framed within the expectation of the final revelation of Christ: “we eagerly await a Savior from there, the Lord Jesus Christ, who, by the power that enables him to bring everything under his control, will transform our lowly bodies so that they will be like his glorious body” (Phil 3:20b–21). While Paul focuses on the future subjection of all things to Christ in Philippians, in Colossians he emphasizes Christ’s inaugurated rule, as Christ has already defeated his enemies on the cross and through his resurrection (2:14–15). In both contexts, the call to focus on heavenly things is grounded on the lordship of Christ, the consummation of which lies in the future when all believers will be glorified with Christ (3:4).

3:2b Not things on the earth (μὴ τὰ ἐπὶ τῆς γῆς). The second way this verse goes beyond v. 1 is the presence of the polarity between “above” and “earth.” Not only is Paul calling believers to focus intently on the things above, but he also urges them to reject “things on the earth.” This contrast is meaningful in various ways. First, the contrast is comparable to that of the “flesh” and the “spirit” elsewhere. If so, to reject the “things on the earth” is to reject the earthly desires.16 This reading is supported by the note on “earthly parts” in v. 5, which introduces the vice lists that follow (vv. 5, 8; see comments below).

Second, if “above” is defined as the place “where Christ is, seated at the right hand of God” (v. 1), the “things on the earth” are practices that refuse to acknowledge Christ as the sovereign Lord of all. The contrast between “above” and “earth” can then be compared to that of “human tradition” and “Christ” (2:8), and even of “shadow” and “substance” (2:17). The use of this polarity is then polemical in intent, as Paul argues against any practices that distract one from worshiping the one and only rightful object of worship.

Finally, the use of this polarity may also be an intentional critique of the dualistic framework assumed by the false teachers. Their ascetic practices may assume a body-soul dualism as they seek to transcend the constraints of the material world. Earlier in this letter, however, Paul has already noted that in Christ “all things were created, in heaven and on earth” (1:16). Moreover, through his death on the cross, all things were reconciled to him, “whether things on earth, or things in heaven” (1:20). In this context, therefore, Paul is not assuming the same metaphysical dichotomy; he is rather using such categories in an attempt to transform the perspective of his audience. Believers are not to escape from this material world; rather, they are to focus on Christ as they live faithfully on earth: “It is in their corporeal body that the community should be oriented toward God’s will, and thus, as v 4 goes on to say, toward God’s future consummation.”17 As such, believers can acknowledge Christ to be both creator and sustainer of both the heaven and the earth.

3:3 For you have died, and your life is hidden with Christ in God (ἀπεθάνετε γάρ, καὶ ἡ ζωὴ ὑμῶν κέκρυπται σὺν τῷ Χριστῷ ἐν τῷ θεῷ). Providing the grounds for the call to focus on the things above, Paul again points to the believers’ death with Christ. In light of 2:20, “you have died” here points to both their identification with Christ and their liberation from the evil powers. Mentioned together with their being “raised with Christ” (3:1), this death is not a sign of weakness but a sign of empowerment in Christ as he defeated the power of death in his resurrection.

With the plural pronoun “your” (ὑμῶν), the singular “life” (ἡ ζωή) should be considered as a “distributive singular,” where the individual person among the wider group is in view.18 This “life” is the present existence of believers as they participate in the resurrection of Christ. The continuity of this “life,” which bridges the present experience of God’s salvation and the future consummation, reappears in the final revelation of Christ’s glory in v. 4.

That this life “is hidden with Christ” is significant in a number of ways. First, the verb “to hide” (κρύπτω) can signify close association (cf. Luke 13:21),19 and this meaning is certainly present in light of Paul’s identification of Christ as “your life” (ἡ ζωὴ ὑμῶν). To be “hidden with Christ” reaffirms the believers’ participation in Christ’s death and resurrection as they anticipate the final consummation of God’s salvific act at the end of time.

Second, to be “hidden with Christ” necessarily implies the security that one finds in Christ.20 The following verse explains the purpose of this hiddenness as it guarantees the final participation of believers in the revelation of God’s glory. This security from the evil powers is also implied in the reference to their dying with Christ, an act that points to the freedom of the threats posed by the opposing spiritual powers (2:20).

Third, in light of 2:3, where Paul asserts that in Christ “all the treasures of wisdom and knowledge are hidden,” Paul is here affirming that the lives of believers are also contained in Christ. This may serve a polemical purpose as Paul argues against those who continuously seek to get access to the heavenly mysteries. Paul’s response is that believers are already hidden with all the treasures in Christ. The sufficiency of Christ cannot be challenged, and to seek for these treasures elsewhere is to betray the true gospel.

Related to this polemical purpose is the redefinition of this hiddenness in historical rather than mystical terms.21 This redefinition can already be found in 1:26, where the “the mystery [that is] hidden” is defined in historical terms as it is “now revealed to his saints.” In the present context, this hiddenness likewise anticipates the final revelation of glory (3:4). This hope not only explains the lack of full manifestation of divine power and glory in believers who live in the present age; this anticipated manifestation of the full glory of God also obviates the need to focus on the present attainment through ascetic practices and visionary experiences.

Finally, this association with Christ may reveal the true identity of believers that can be found only in Christ. This reading finds its parallel in Rom 2:28–29, where the “hidden” word group is used in the definition of the true people of God: “someone is a Jew who is one inwardly” (NET).22 When the lives of believers are identified with Christ in v. 4, therefore, it is not simply association but also identity that is at issue. Instead of identity markers that provide external identification of those who follow the false teachers (2:11, 16, 20–21), the Colossian believers are called to identify themselves simply in reference to Christ.

Although translated as “in God” (ἐν τῷ θεῷ) in most modern versions, it is possible to take this phrase in an instrumental sense: “your life is hidden in Christ by God”23 (cf. Eph 3:9). Nevertheless, one does not find an instrumental use of ἐν in this letter when final agency in reference to God the Father is in view. Some have taken it in a locative sense and have made it explicit in their translation: “your life is hidden with Christ, who sits beside God” (CEV). It is perhaps best to see this prepositional phrase as indicating close identification since Christ is to be identified as God; as such, “its christological weight is wholly of a piece with the Wisdom Christology of the hymn in 1:15–20.”24 The unbreakable bond between believers, Christ, and God the Father is here established. It is this bond that provides the security for believers as they await the final fulfillment of God’s plan in history.

3:4a-b When Christ is revealed, who is your life (ὅταν ὁ Χριστὸς φανερωθῇ, ἡ ζωὴ ὑμῶν). The note on the hiddenness of an object demands a discussion about its revelation. Here, Paul adopts a temporal framework that accommodates this polarity. The intense christocentric focus is again reflected as Paul describes the destiny of believers in terms of the consummation of God’s salvific plan in Christ.

The verb “is revealed” (φανερωθῇ) is unexpected in the description of the return of Christ at the end of times, and this word choice has led some to conclude that Paul is not referring to Christ’s second coming here. According to this reading, since dying and being hidden do not refer to the physical death and burial of believers, neither should “is revealed” refer to the physical return of Christ with his followers. Instead, one should read the verse in the following sense: “If you let it become visible that Christ is your life, then to his glory it will also become manifest that you have been raised to a new life with him.”25 The discussion that follows (3:5–4:1) then points to this manifestation of Christ’s glory in the daily living.

This noneschatological reading is unlikely, however, and a response to this reading sheds light on the function and significance of this verse. This reading downplays the references to the future in this letter. “The hope of glory” in 1:27 clearly points to the consummation of glory at a future point in time. An eschatological emphasis is also apparent in this section, where Paul points to “the wrath of God” in 3:6, a phrase often found in eschatological contexts. The call to be “alert” in 4:2 likewise evokes a similar context. Therefore, a reference to the revelation of Christ cannot be limited to present Christian living.

The choice of the verb “is revealed” (φανερωθῇ) is anticipated by the reference to hiddenness in v. 3, and should therefore not be used as an argument against an eschatological reading (cf. 1:26). Hiddenness itself is a concept familiar in eschatological contexts as it “reflects the apocalyptic conviction that what will be revealed in glory is hidden for the duration of the present age (e.g., 2 Bar. 48.49; 52.7).”26 Although not a technical term in reference to the parousia, the verb “to reveal” has been used in reference to the manifestation of all deeds in eschatological judgment (2 Cor 5:10).

Finally, the significance of the pair “when” (ὅταν) and “then” (τότε) must not be missed. This pair points to a reality that has not been realized—a pair that naturally follows the death and resurrection/exaltation of Christ. Elsewhere in Paul, one also finds references to the death, resurrection, and return of Christ mentioned together (esp. 1 Cor 15, where Paul discusses the identification of believers with Christ in his death and resurrection, which thus provides the basis of the future hope when he returns in glory):

But Christ has indeed been raised from the dead, the firstfruits of those who have fallen asleep. For since death came through a man, the resurrection of the dead comes also through a man. For as in Adam all die, so in Christ all will be made alive. But each in turn: Christ, the firstfruits; then, when he comes, those who belong to him. Then the end will come, when he hands over the kingdom to God the Father after he has destroyed all dominion, authority and power. (1 Cor 15:20–24)

In this context, the return of Jesus likewise justifies the hope that believers place in his resurrection. Although our present living out of the power of the risen Lord is the emphasis of the following verses, this life is grounded in the historical events that have and will take place according to the salvific plan of God.

“Who is your life” (ἡ ζωὴ ὑμῶν)27 renders the phrase literally translated as “your life.” This phrase stands in apposition to “Christ.” Paul moves here from association to identification: “It is not enough to have said that the life is shared with Christ. The apostle declares that the life is Christ.”28 This identification is critical to Paul’s argument and should not be limited to one particular set of relationships, as is illustrated in CEV: “Christ gives meaning to your life.” One’s identification with Christ in the context of the outworking of his death and resurrection can also be found elsewhere in Paul:

We always carry around in our body the death of Jesus, so that the life of Jesus may also be revealed in our body. For we who are alive are always being given over to death for Jesus’ sake, so that his life may also be revealed in our mortal body. So then, death is at work in us, but life is at work in you. (2 Cor 4:10–12; cf. Gal 2:20; Phil 1:21)

In this section in Colossians, however, Paul extends this identification to the final revelation of Christ’s glory.

3:4c Then you also will be revealed with him in glory (τότε καὶ ὑμεῖς σὺν αὐτῷ φανερωθήσεσθε ἐν δόξῃ). This final clause draws out the implication of the believers’ identification with Christ. The reuse of the verb “reveal” in “you will be revealed” (φανερωθήσεσθε), together with the phrase “with him” (σὺν αὐτῷ), points to the ultimate goal of our identification with Christ. This appearance in glory justifies our present hiddenness.

Paul does not explain the significance of the reference to “in glory” (ἐν δόξῃ) in this context, except that this is the fulfillment of the longings of believers. Elsewhere in Paul, this glory often consists of Christ’s ultimate victory over death when believers will be clothed with an immortal body (1 Cor 15:53–54; cf. Rom 2:7; 6:4; 1 Thess 4:16–17). This fits this context well, although earlier in this letter, Paul also pointed to the glory in the ultimate manifestation of the power of God through Christ (1:11) and the fulfillment of God’s plan in history (1:27). This glorious note becomes a significant anchor for the Colossians as they seek to be faithful to the gospel in which they are called. After all, these “insignificant ex-pagans from a third-rate country town”29 will participate in a glory that encompasses all creation, and it is to this cosmic vision that their identities are to be grounded.

3:5a Put to death, therefore, your earthly parts (Νεκρώσατε οὖν τὰ μέλη τὰ ἐπὶ τῆς γῆς). This verse begins with the particle “therefore” (οὖν), which signals another stage of Paul’s argument (cf. 2:6, 16; 3:1) as it builds on the previous call to focus on the risen Christ (3:1) and “the things above, not things on the earth” (3:2) while awaiting the full revelation of Christ’s glory (3:4). The list of vices to be avoided represents the “things on the earth.”

“Put to death” (νεκρώσατε) is built on the previous assertion that “you have died” (v. 3). The relationship between the previous indicative statement and the present aorist imperative must be noted. In the preceding discussion, Paul has emphasized the active work of God through Christ on behalf of those who believe in him. God is the one who “delivered us from the dominion of darkness and transferred us into the kingdom of his beloved Son” (1:13), and this is accomplished through “the blood of his [Christ’s] cross” (1:20). While believers are called to participate in Christ’s death and resurrection (2:11–12), Paul makes it clear that God has destroyed all opposing forces through Christ’s death on the cross (2:14–15). In this context, therefore, the call to “put to death” the old practices is to be balanced by the recognition that Christ’s death allows such an imperative to be a possibility. Moreover, this call is also based on the fact that believers were already “dead in [their] transgressions” (2:13). This call to “put to death” the old self is the living out of the victory that has already been won.

This call, therefore, means: “let the old man, who has already died in baptism, be dead.”47 This relationship between the indicative and the imperative is best explicated in an earlier Pauline letter:

For we know that our old self was crucified with him so that the body ruled by sin might be done away with, that we should no longer be slaves to sin—because anyone who has died has been set free from sin…. Count yourselves dead to sin but alive to God in Christ Jesus. Therefore do not let sin reign in your mortal body so that you obey its evil desires. (Rom 6:6–7, 11–12)

To “put to death” means to live with a recognition that one is already freed from the power of sin. This relationship between the imperative and the indicative is reflected in versions that translate the imperative as “consider … as dead” (NASB) or “don’t be controlled by” (CEV).

The direct object of putting to death is “your earthly parts” (τὰ μέλη τὰ ἐπὶ τῆς γῆς). The second article followed by the prepositional phrase functions as an adjectival modifier, thus “earthly.” “Your … parts” is commonly used in reference to body parts (see esp. 1 Cor 12:12–16). Since in Jewish traditions evil deeds are often related to the various parts of the body, some have taken “your earthly parts” as referring to these various parts doing various types of sins. “Your earthly parts” then refers to “your limbs as put to earthly purposes.”48 The translation adopted here assumes this background. Nevertheless, since the vice list that follows focuses primarily on sexual sins, it is also possible to read this phrase as referring to the general sinful nature of unredeemed humankind—thus, “whatever belongs to your earthly nature” (TNIV, NIV; cf. NET), or even “the sinful, earthly things lurking within you” (NLT).

3:5b-g Sexual immorality, impurity, lust, evil desires, and covetousness, which is idolatry (πορνείαν, ἀκαθαρσίαν, πάθος, ἐπιθυμίαν κακήν, καὶ τὴν πλεονεξίαν ἥτις ἐστὶν εἰδωλολατρία). This list provides examples of the believers’ past unredeemed nature.49 The first four items are directly related to sins of a sexual nature. “Sexual immorality” refers to various kinds of sexual transgressions; in the OT, it is also connected with idolatrous practices (Isa 47:10; Jer 3:9; Ezek 23:8; Mic 1:7; cf. Exod 34:15–16; Deut 31:16).50

“Impurity” is often used in reference to cultic impurity in the OT (Lev 5:3; 15:3, 30–31; 16:16; 22:4–5; Num 19:13; Judg 13:7; 2 Chr 29:5, 16), but it also appears in contexts where sexual immorality (Hos 2:10 [LXX 2:12]) and idolatry (Jer 19:13; 32:34 [LXX 39:34]; Ezek 7:20; 36:25) are discussed. In Paul, it is also often used in relation to sexual immorality (Rom 1:24; 2 Cor 12:21; Gal 5:19)51 although it can refer to the general rejection of the holiness of God (1 Thess 4:7).

“Lust” (πάθος) literally reads “passion” (ASV, NAB, NASB, NRSV, NKJV, ESV), but in this context it most likely refers to “shameful passion” (NET) of a sexual nature.52 This is confirmed by its use elsewhere in Paul, especially when this is used to characterize “the pagans, who do not know God” (1 Thess 4:5; cf. Rom 1:26).

“Evil desires” (lit., “evil desire,” ἐπιθυμίαν κακήν) can refer to sinful desires in general (e.g., Rom 6:12; 7:8; 13:14; Gal 5:16) but in this context also likely refers to illicit sexual passion (e.g., Rom 1:24; 1 Thess 4:5). This term serves as a transition to the last vice, as the relationship between “evil desires” and “covetousness” is made clear in Rom 7:7: “I would not have known what coveting [ἐπιθυμίαν] really was if the law had not said, ‘You shall not covet’ ” (Rom 7:7; cf. Exod 20:17; Deut 5:21).53

The final item, “covetousness” (πλεονεξίαν), together with the descriptive phrase, “which is idolatry,” points to the background of this list in the Ten Commandments. The general background of the Ten Commandments to NT vice and virtue lists has already been noted,54 and this is particularly clear in here.55 Following various expressions of sexual transgressions, Paul ends with the command against covetousness (cf. Exod 20:17; cf. Deut 5:21). In the OT, this tenth commandment properly concludes the Ten Commandments in two ways. First, it is obviously different from the previous ones in that it “deals with motivation rather than action,” especially “motivations behind the crimes … of commandments six through nine.”56 Second, it points back to the first set of commandments since all the crimes reflected in these commandments find their roots in their refusal to worship the one true God and thus are forms of idolatrous practices.

Although grammatically the phrase “which is idolatry” modifies only “covetousness,” “covetousness” reflects the motive behind all the preceding vices. Paul instructs believers to avoid the various sexual vices because they are manifestations of covetousness, a general and comprehensive vice that points to the refusal to submit to the lordship of Christ. Paul is not randomly imposing a new list of selected regulations; rather, he is calling the believers to reject their idolatrous past and to worship the one Lord of all.

3:6 Because of these the wrath of God is coming [upon the sons of disobedience] (δι’ ἃ ἔρχεται ἡ ὀργὴ τοῦ θεοῦ [ἐπὶ τοὺς υἱοὺς τῆς ἀπειθείας]). Paul uses the phrase “the wrath of God” to underline the significance of the above call to faithful living. Although the present manifestation of God’s wrath is not foreign to Paul’s thought (e.g., Rom 1:18–32), in light of the reference to the final revelation of Christ’s glory in v. 4, it seems best to take this as a reference to the eschatological wrath of God to be revealed at the final judgment (cf. Rom 2:5; 5:9; 9:22; 1 Thess 1:10).57 The contrast between participation in the final revelation of glory and the experience of God’s wrath is illustrated in Rom 2:7–8:

To those who by persistence in doing good seek glory, honor and immortality, he will give eternal life. But for those who are self-seeking and who reject the truth and follow evil, there will be wrath and anger.

Although one’s evil deeds precipitate the final manifestation of God’s wrath, one’s good deeds cannot deliver that person from that wrath. Elsewhere, Paul makes it clear that for those who turn from idols, Jesus delivers them from God’s coming wrath:

They tell how you turned to God from idols to serve the living and true God, and to wait for his Son from heaven, whom he raised from the dead—Jesus, who rescues us from the coming wrath. (1 Thess 1:9–10)

Therefore, one should not downplay God’s salvific act through Christ (1:12–14, 20–23; 2:11–15) when the evil deeds to be avoided by believers are listed.

The authenticity of the prepositional phrase “upon the sons of disobedience” (ἐπὶ τοὺς υἱοὺς τῆς ἀπειθείας) is uncertain, and it is not included in some modern versions.58 The appearance of this phrase in Eph 5:6 may have prompted some early scribes to insert it into this context, and it is not found in two of the earliest and most reliable manuscripts.59 Both the internal and external evidence seem to provide a slightly stronger case for its omission. Thus, it is best to include it in parentheses (see UBS4 and NA27).

Regardless of whether the phrase comes from the parallel in Eph 5:6, Eph 2:2–3 is equally relevant as Paul describes the believers as those who formerly belong to “the sons of disobedience” and were “by nature the children of wrath” (NASB). Here in Colossians, Paul is likewise calling believers to reject their former lives as those who were “once alienated and hostile in mind” (1:21). The notes on “the wrath of God” and “the sons of disobedience” point again to the function of the vice list as providing the definition of God’s people and thus consolidating the boundary between those who belong to Christ and those who refuse to submit to his lordship. The distinction is not simply a sociological one, for Paul emphasizes the eternal relevance for one’s faithful submission to Christ.

3:7 In these you once walked, when you were living in them (ἐν οἷς καὶ ὑμεῖς περιεπατήσατέ ποτε ὅτε ἐζῆτε ἐν τούτοις). Paul now makes it explicit that in the vice list above, he is characterizing the former life of the (Gentile) believers. Taken as a neuter relative pronoun, “these” (οἷς) most likely refers to the sins listed in v. 5.60 Paul is criticizing the believers for participating in the sinful practices that characterized unbelievers.

The significant change in one’s way of living has already been noted in 2:6, where Paul likewise adopted the metaphor of walking: “just as you received Christ Jesus the Lord, continue to walk in him.” The contrast between their former lives and their present existence in Christ is highlighted by the temporal indicator “once” (ποτε), which has already appeared in 1:21: “you were once [ποτε] alienated and hostile in mind through evil deeds.” The list in 3:5 has elaborated on such “evil deeds.” In Paul, vice lists are often used to describe the former pattern of those now redeemed by Christ, and the content of the two vice lists here (vv. 5, 8) merges in Paul’s later writings to make the same point (see Titus 3:3; cf. 1 Cor 6:9–11).61

The second part of the verse (“when you were living in them”) seems redundant.62 Word order in Greek, however, points to a chiastic structure with “then” and “when” at the center, highlighting the former pattern of behavior of these believers:

- A In these (ἐν οἷς)

- B you walked (καὶ ὑμεῖς περιεπατήσατε)

- C once (ποτε)

- C´ when (ὅτε)

- B´ you were living (ἐζῆτε)

- B you walked (καὶ ὑμεῖς περιεπατήσατε)

- A´ in them (ἐν τούτοις)

This emphasis on the past (“once” and “when”) paves the way for the next verse, which begins with yet another temporal particle, “but now” (νυνί δέ). The contrast between the former life and the present status as followers of Christ becomes clear.

Others have also attempted to make sense of this apparent tautology by noting a development from the first to the second half of the verse. Drawing on the difference in nuances between “you … walked” and “you were living,” some see the first part as focusing on “actual conduct” while the second describes a “general lifestyle,”63 while others see the first as “the condition of their life” and the second as the “character of their practice.”64 While a semantic analysis of the two words may not justify such a distinction, in context a progression of thought seems clear. In light of 2:6, the metaphor of walking provides a general context in reference to lifestyle and behavior, while “living” points back to 2:20, where Paul makes a distinction between living in the world and dying to it with Christ. “Living” thus points more specifically to the life-death-resurrection metaphor used throughout this letter (1:18–20; 2:11–12, 13–14, 20). In any case, Paul is clearly calling believers to die to their former life as they participate in the worship of the risen Christ (3:1).

3:8 But now you also must put all these away: anger, rage, malice, slander, and abusive speech from your mouth (νυνὶ δὲ ἀπόθεσθε καὶ ὑμεῖς τὰ πάντα, ὀργήν, θυμόν, κακίαν, βλασφημίαν, αἰσχρολογίαν ἐκ τοῦ στόματος ὑμῶν). With this second list of vices, Paul shows how believers should act in building up their community in unity and love. “Put … away” (ἀπόθεσθε) can refer to the general action of “to get rid of” (NLT), but in this context it may be related to the specific metaphor of putting away one’s clothing. Elsewhere in Paul, this word is always used with the contrastive verb “to put on” (ἐνδύω, Rom 13:12–14; Eph 4:22–25), a verb also used by Paul in the arguments that follow (vv. 10, 12).65 In other NT writings, however, the verb is also used in the general sense of getting rid of evil practices (Jas 1:21; 1 Pet 2:1).

The meaning of this verb depends on whether the various vices are to be considered as a group or whether the final phrase (“from your mouth”) modifies all the members of this group. Defining the phrase “from your mouth” more narrowly, many understand it as attaching “to the end of the last as a way to reinforce the last two sins.”66 This reading is explicit in some versions: “But now you must get rid of all these things: anger, passion, and hateful feelings. No insults or obscene talk must ever come from your lips” (GNB).

In this context, however, it is best take “from your mouth” as referring to the entire group of vices: “But now have done with rage, bad temper, malice, slander, filthy talk—banish them all from your lips” (REB). First, since the final phrase in the previous list (“which is idolatry”) modifies all the items, this last modifying phrase should likewise be understood that way. Elsewhere in Paul, evil speech out of one’s mouth can also be understood as symbolizing a general refusal to worship God (Rom 3:10–18). Moreover, the “mouth” is portrayed as the primary vehicle through which one can submit to the lordship of Christ: “If you declare with your mouth, ‘Jesus is Lord,’ and believe in your heart that God raised him from the dead, you will be saved” (Rom 10:9). The various vices listed here are but expressions of one whose mouth refuses to confess Jesus as one’s Lord.

This understanding is confirmed by Paul’s subsequent arguments when he suggests that one should ground one’s behavior in thanksgiving and praise (vv. 15–17). This contrast between sinful behavior as symbolized by one’s evil speech and a life of worship is best illustrated by two other NT passages. First, in the parallel passage in Eph 5, after a list of sexual sins (Eph 5:3), Paul turns to a list of vices all related to speech: “obscenity, foolish talk [and] coarse joking” (Eph 5:4). This not only lends support to reading the second vice list in Col 3 as one that focuses on speech, but the alternate behavior Paul recommends also sheds light on the reasons behind his mentioning of such vices: “but rather thanksgiving” (Eph 5:4). This call to “thanksgiving” is a call to worship and confess God and his mighty deeds on behalf of his people.67 The underlying problem behind those involved in evil speech is a refusal to worship God and submit to the lordship of his Son.

A second passage (one outside of Paul’s letters) further confirms this reading. After a critique of those who cannot control their tongues (Jas 3:1–6), James provides the basis of such a critique in the need to choose between praising God with one’s mouth and cursing others with the same mouth:

With the tongue we praise our Lord and Father, and with it we curse human beings, who have been made in God’s likeness. Out of the same mouth come praise and cursing. My brothers and sisters, this should not be. Can both fresh water and salt water flow from the same spring? (Jas 3:9–11)

In Col 3, Paul appears to be making a similar argument. From a mouth that refuses to confess the singular lordship of Christ, one finds various kinds of evil acts and patterns of behavior. As such, this list is related to the previous catalogue in v. 5 in that both lists point to manifestations of acts of idolatry; and even though “from your mouth” modifies the entire list, the individual vices noted in this list are not limited to explicit verbal sins.

“Anger” (ὀργή) and “rage” (θυμός) have overlapping semantic fields. In the LXX, they often refer to the wrath of God (e.g., Num 12:9; 14:34; 32:14; Deut 13:17 [LXX 13:18]; Josh 7:26; 2 Chr 28:11; Isa 5:25), and in Paul they also appear with other vice lists (Eph 4:31). Although in certain contexts “anger” can denote “a more or less settled feeling of hatred” while “rage” refers to “a tumultuous outburst of passion,”68 this distinction is not obvious in the biblical texts when the two terms are used together. If the manifestation of “anger” and “rage” in the OT is primarily the right of the sovereign and holy God, such behavior among human beings usurps divine right while assuming that one can function similarly as the ultimate judge.

“Malice” (κακία) also appears in NT vice lists (cf. Rom 1:29; Eph 4:31; Titus 3:3; 1 Pet 2:1). It can refer to evil disposition or even “malicious behavior” (NLT) that results from such a disposition. In Greco-Roman literature, the term often contrasts to “virtue” (ἀρετή) and can refer to the general “quality or state of wickedness.”69

“Slander” (βλασφημία) can acquire the specific sense of “blasphemy” (KJV, NKJV) against God (Matt 12:31; 26:65; Mark 14:64; Luke 5:21; John 10:33; Rev 13:1, 5–6; 17:3), but it also appears in other vices for defamatory speech against others (Matt 15:19; Mark 7:22; Eph 4:31; 1 Tim 6:4). It is possible, however, that speaking against others should be understood as an act of blasphemy because to do so is to “curse human beings, who have been made in God’s likeness” (Jas 3:9).

Finally, “abusive language” (αἰσχρολογία) can refer more specifically to “obscene language” (NAB) or even “dirty talk” (NJB; cf. NLT). In light of a related word in Eph 5:4 (αἰσχρότης, “obscenity,” NIV) in the context of coarse and inappropriate speech, this narrower definition is not impossible. Nevertheless, since all previous vices are related primarily to displays of anger, a more general reference to “abusive language” is more likely. Although occurring only here in the NT, this term appears in extracanonical vice lists for abusive speech.70 If so, this list points to expressions of anger that prevent one from participating in the community of God’s people, which is characterized by unity and love (vv. 12–14).

3:9a Do not lie to one another (μὴ ψεύδεσθε εἰς ἀλλήλους).71 Concluding his discussion on vices, Paul urges the believers to live a life in truth. This isolated call is often considered as yet another command that grows from the concerns expressed above: “The same concerns for relationships of mutual confidence and respect continue in a warning against lying to one another.”72 It is best to consider this call as summarizing the previous list that involves primarily the sins “from your mouth” (v. 8).73

The act of lying should not be considered simply as a verbal act of making a false statement. In the biblical material, to lie is to deny the Truth as represented by God himself. This is best illustrated in Paul’s own statement in Romans: “They exchanged the truth about God for a lie, and worshiped and served created things rather than the Creator—who is forever praised. Amen” (Rom 1:25). Significantly, this verse also appears in a vice list that depicts the sinful behavior of the Gentiles (1:26–30), and it mentions the act of lying as these Gentiles worship idols instead of the Creator God. This accusation reappears in Rom 2:8: “But for those who are self-seeking and who reject the truth and follow evil, there will be wrath and anger.” To Paul, therefore, the act of lying is an active denial of the truth that can only be found in God. “Do not lie,” therefore, provides the proper conclusion to the vice list in v. 8, and the fact that lying is to be equated to idolatry also links this second list with the first (v. 5).

“To one another” provides the link between offenses directed against God and those against others. As lying is understood as an idolatrous act, lying “to one another” is to act within a community that denies the truth of God. The same connection between vertical and horizontal relationships is also expressed by this reciprocal pronoun in v. 13, where Paul urges believers to “forgive one another” as they have been forgiven by God. This pronoun points to the community as the context through which vices are to be avoided and virtues to be practiced (cf. vv. 10–12).

3:9b For you have taken off the old humanity with its practices (ἀπεκδυσάμενοι τὸν παλαιὸν ἄνθρωπον σὺν ταῖς πράξεσιν αὐτοῦ). Paul now grounds the previous exhortation with a note on their new identity in Christ. Although considered by some to be an imperatival participle,74 “for you have taken off” is best taken as a causal adverbial participle providing the grounds for the previous all-encompassing call to recognize and acknowledge the truth. This distinction is important because the act of taking off the old humanity is already an accomplished fact, and Paul is pointing instead to the implications of that act.75

In light of 2:11–15, where one also finds the metaphor of taking off clothing (ἀπεκδυσάμενος, v. 15), this participle likely reflects the background of baptism, when believers participate in the death and resurrection of Christ. Together with the call to “put on” (ἐνδύσασθε) in v. 12, however, this pair also points to the use of the clothing metaphor.76 Some have understood the coexistence of these two metaphors as rooted in OT practice, where the priest washed himself with water before clothing himself with the sacred garment as he approached God (cf. Exod 29:4–9; Lev. 16:3–4).77

This clothing metaphor also likely alludes to the Adam account in Genesis. As God provided a new set of clothing for the fallen humans (Gen 3:7, 21), here Paul uses this change of clothing to signify the believers’ “inaugurated new-creation relationship with God.”78 The reference to the new creation (“according to the image of their Creator”) in v. 10 confirms this allusion. Elsewhere in Paul, “the old humanity” refers to “the body ruled by sin” (Rom 6:6). In the present context, Paul points not only to the regeneration of one’s nature, but also to the new community that is created, a community that bears the image of God. For those reading through the lens of individualism, the climactic statement in v. 11 is surprising since it defines not one’s inner being but the new community of God’s people: “where there is neither Greek nor Jew, circumcised nor uncircumcised, barbarian, Scythian, slave nor free” (v. 11).

Paul’s assertion here is a natural progression of his arguments begun in 1:15–20, where the church is identified as the body of Christ in the new creation (1:18). Unlike the false teachers, who seem to have focused on private religious experience, Paul focuses on a community of regenerated persons who testify to God’s work through Christ in the new created order. In this reading, “the old humanity” refers to those who belong to the old lineage of the first Adam, while “the new humanity” belongs to Christ (cf. 1 Cor 15:22, 45). Though these phrases have often been rendered as “the old/new man” (KJV, ASV, NKJV, NET, HCSB) or “the old/new self” (NAB, NASB, NRSV, NJB, GNB, TNIV, ESV, NIV), in light of Paul’s emphasis on the creation of a new community, “the old/new humanity”79 best captures Paul’s intention here as these phrases “derive their force not simply from some individual change of character, but from a corporate recreation of humanity.”80

3:10 And have put on the new humanity, being renewed in knowledge according to the image of their Creator (καὶ ἐνδυσάμενοι τὸν νέον τὸν ἀνακαινούμενον εἰς ἐπίγνωσιν κατ’ εἰκόνα τοῦ κτίσαντος αὐτόν). Corresponding to the act of taking off “the old humanity” (v. 9), Paul calls the believers to “put on the new humanity.”81 Like the participle “taken off,” “put on” is also a causal adverbial participle providing further grounds for Paul’s previous call to avoid behavior that reflects the “old humanity.” Clearly, Paul has fully shifted to the clothing metaphor as he points to a decisive and drastic change brought by the cross and resurrection.

The presence of the attributive participle “being renewed” (ἀνακαινούμενον), which modifies the substantive “the new [humanity]” (τὸν νέον), may appear to be a paradox: “the new being renewed again.”82 The juxtaposition of these terms is important for a number of reasons. First, “the new humanity” points to the decisive incorporation of believers in Christ, while the participle “being renewed” points to the ongoing participation of believers as they become what they are already. This is consistent with Paul’s emphasis on the daily involvement of believers in this process: “our inner self is being renewed day by day” (2 Cor 4:16 ESV).83 This tension points again to the “already but not yet” tension typical of Pauline theology. For those who only see a realized eschatology in Christian existence, this offers a corrective note.

Second, the passive voice of this participle points to God as the ultimate agent. The temporal tension between God’s past act through Christ and the present Christian involvement is therefore supplemented by the tension between divine agency and human responsibility.

Third, the use of the verb “to renew” (ἀνακαινόω) may also be important in revealing the work of the triune God. In Paul, the renewal of believers is often the work of the Holy Spirit (Titus 3:5; cf. Eph 3:16).84 If so, God calls believers to put on the new humanity created by his new creative act through his Son, and the Spirit continues to work through them as they grow into what has been prepared for them. This tension, therefore, sheds light on the unfolding of God’s plan for humanity through his Son and the Holy Spirit.

“In knowledge according to the image of their Creator” again alludes to the Genesis creation account.85 “Knowledge” may echo the centrality of “knowledge” in the account of the fall in Gen 2–3, so that “being renewed in knowledge” points to the reversal of the effect of the fall through God’s new creative act in Christ. “The image of their Creator”86 clearly alludes to Gen 1:26–27.

In light of the previous reference to Christ’s role in both the old and new creations (1:15–20), it is not impossible to take this “Creator” as Christ himself.87 In this context, however, it is better to take it as a reference to God the Father. In light of the allusion to Gen 1:26–27, a reference to God the Father is to be assumed. Since Christ himself was “the image of the invisible God” in Col 1:15, the christocentric emphasis is retained here, where Paul is urging believers to conform to Christ, who is the perfect image of the Creator. “When God re-creates Man, it is in the pattern of Christ, who is God’s absolute Likeness.”88 As such, the process of renewal is also a christocentric one: “Since man has been created after the image of God, i.e., Christ, assimilation to God must also take place via Christ.”89

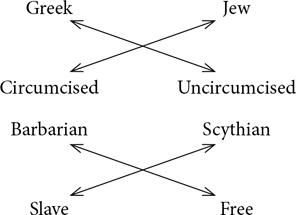

3:11 Where there is neither Greek nor Jew, circumcised nor uncircumcised, barbarian, Scythian, slave nor free, but Christ is all and in all (ὅπου οὐκ ἔνι Ἕλλην καὶ Ἰουδαῖος, περιτομὴ καὶ ἀκροβυστία, βάρβαρος, Σκύθης, δοῦλος, ἐλεύθερος, ἀλλὰ [τὰ] πάντα καὶ ἐν πᾶσιν Χριστός). The climax of this discussion of the “new humanity” comes with this verse, which provides definition for this community. Paul makes it clear that he is not focusing narrowly on the behavior of an individual; rather, his concerns center on the upbuilding of the community of God’s people.

“Neither Greek nor Jew” is a familiar contrastive pair in Paul’s letters.90 It can refer to the different stages in God’s redemptive plan (Rom 1:16; 2:10), and as the basic categories that divide humanity in the eyes of the Jews, this pair can also point to the universal human predicament (Rom 3:9) and the corresponding universal lordship of Christ (10:12; 1 Cor 1:24). Thus, the word “Greek” is not a narrow ethnic label pointing simply to those who are “Greek” by birth; it applies to anyone influenced by Greek culture or, even more broadly, to anyone who is not identified as a Jew (e.g., John 7:35). Some versions have, therefore, justifiably chosen to translate the term “Greek” as “Gentile” (NLT, TNIV, NIV).91

“Circumcised nor uncircumcised” often refers to “Jews” and “Gentiles” respectively, and they also appear elsewhere in contrastive terms (Rom 2:25–27; 3:30; 4:9–12; 1 Cor 7:19; Gal. 2:7; 5:6; Eph 2:11). The point here is well expressed in Gal 6:15, a verse that also refers to the community of God’s new creative act: “Neither circumcision nor uncircumcision means anything; what counts is the new creation.” The presence of a contrastive pair that essentially repeats the preceding phrase, “neither Greek nor Jew,” may be explained by the ethnic barrier set up by the false teachers, who were insisting on certain elements of Jewish identity markers (cf. 2:16–23). The notes on “circumcision” (2:11) and “uncircumcision” (2:13) mentioned above may also have prompted Paul to emphasize this contrastive pair.

The pair “barbarian, Scythian” is more difficult to explain. “Barbarian” often refers to those who do not speak Greek,92 and it is thus considered to be someone who is not only a “foreigner”93 but also “uncivilized.”94 “Scythian” points to the inhabitants north of the Black Sea. The Scythians were often considered to be an extreme example of “barbarian” (i.e., “the lowest type of barbarian”).95 But then this pair appears out of place since the other pairs are clearly contrastive in nature.96 Presupposing a Cynic background of the Colossian false teachers, who may have identified themselves as Scythians, Troy Martin has suggested that this pair should be understood from a Scythian perspective: “From a Scythian viewpoint, the term barbarian means anyone who is a non-Scythian.”97 Paul is then directly reacting against this Cynic perspective in breaking down barriers between different people groups. Attractive though this proposal may be, it is difficult to explain how “Scythian” should be paired with “barbarian” instead of “Greek.”98

A more plausible case has been proposed by Douglas Campbell, who suggests that Scythians are to be understood as “slaves,” and they are opposed to the free “barbarians.”99 This proposal not only maintains the contrasting nature of this pair, but it also explains the relationship between the first and second pair, and thus the third and fourth:

Paul is therefore arguing against the distinction between circumcised Jews and uncircumcised Greeks, and also that between free barbarians and Scythian slaves. Although this theory may lack extensive literary support,100 this would at least explain both the structure and the content of this series.

The final pair, “slave nor free,” is an obvious pair that points to contrastive social status; it has appeared both in Paul in a literal (1 Cor 12:13; Gal 3:28) and a metaphorical sense (Rom 6:20; 1 Cor 7:21–22; Eph 6:8), and elsewhere in the NT (1 Pet 2:16; Rev 6:15; 13:16; 19:19). A discussion of the relationship between master and slave also appears in 3:22–4:1. Paul grounds his critique of the social division of his time in the theological affirmation that we have all been slaves to sin, and freedom can only be found in Christ: “For the one who was a slave when called to faith in the Lord is the Lord’s freed person; similarly, the one who was free when called is Christ’s slave” (1 Cor 7:22; cf. Gal 4:21–31).

These contrasts are consistent with Paul’s statement elsewhere when he affirms the unity brought by God’s redemptive work through Christ: “There is neither Jew nor Gentile, neither slave nor free, nor is there male and female, for you all are one in Christ Jesus” (Gal 3:28; cf. 1 Cor 12:13). The lack of the gender pair in Col 3:11 list may be explained by the subsequent discussion of husband and wife in 3:18–19,101 though this would not explain the presence of the slave-free pair in spite of its reappearance in 3:22–4:1. More likely Paul formulates this structure in light of the challenges the Colossian believers are facing. It seems that ethnic and class distinction played a part in the formulation of the false teachings, but gender seems less of an issue.102

The portrayal of the unity of this new humanity is important for Paul as he points to the impact of the universal reconciliation achieved by Christ’s death and resurrection (1:18–20; cf. 2:15). This is expressed in the final clause: “Christ is all and in all.” Here, however, the “all” moves from cosmological affirmations to its ecclesiological significance: since Christ has conquered all, all peoples now can participate in this one body. As such this gospel, which centers on Christ’s work, is proclaimed all over the world (1:6, 23). Behind this affirmation of the unity of God’s people is also the recognition of the diversity found in this new humanity,103 and each group will play a part as they live out Christ’s lordship.

Finally, this cosmological and ecclesiological reality also carries its own ethical impact, and this present section points precisely to a new heavenly perspective even for earthly living (cf. 3:1–4).104 In further unpacking this “all and in all,” Paul will continue to demonstrate the relevance of this confession for both the community of God’s people (3:12–4:1) and those presently outside this community (4:2–6).

Theology in Application

Spirituality and Eschatology

Reading through Col 2, where one finds Paul criticizing the false teachers for their promotion of the worship of heavenly beings (2:18), the readers may be surprised to find the call to “seek the things above” (v. 1) at the beginning of a section that contains exhortation for the believers (vv. 1–4). In numerous ways, however, Paul makes it clear that he is not calling his readers to return to the search for spiritual fulfillment in their particular experiences as they seek to encounter those heavenly beings.

First, instead of esoteric experiences, Paul points to Christ alone, who is “seated at the right hand of God.” This distinct christocentric perspective is consistent with his arguments earlier (cf. 1:15–20; 2:8, 13–15, 16–17) as Paul emphasizes that the only proper goal of any spiritual journey is Christ and he alone.

Second, while this section begins with the call for believers to act, the focus quickly shifts to the act of Christ himself. As one’s “life is hidden with Christ in God” (v. 3), one’s fulfillment depends only on God’s further work in and through Christ.

Third, since one’s fulfillment is dependent on the act of Christ and not one’s ability or achievement, all who have been “buried with him in baptism” (2:12) are able to gain access to this fulfillment, which can be found in Christ. Instead of a private and elitist experience, therefore, Paul emphasizes the universal accessibility of the powerful work of the cross, one that brings reconciliation to all things, “whether things on earth, or things in heaven” (1:20).

Finally, and perhaps most striking of all, Paul introduces the eschatological perspective, when he mentions the future participation of the revelation of Christ’s glory at the end times. The glory that one seeks in one’s private religious experiences through either heavenly ascent or the worship of heavenly beings is to be superseded by the public revelation of Christ’s glory, when all who have died and have been raised in him can find true fulfillment in this consummation of God’s work in Christ.

In numerous ways, this eschatological perspective is critical for appreciating a spirituality that is faithful to the gospel message. The reference to the revelation of “Christ … in glory” in the end times is but the consummation of God’s work in Christ through his death and resurrection. For believers, the death, resurrection, and return of Christ form the basis of any call to faithful living. Again, one finds the indicative as the basis of the imperative, which is “just the reverse of Aristotelian and indeed all human religious approaches to holiness.”105

In repeatedly emphasizing the mighty acts of God through Christ, Paul calls believers to abandon their self-centered preoccupation with their statuses, even their spiritual statuses, as they participate in the metanarrative with Christ at the center of this drama of salvation. This is then another call to abandon an idolatrous life and turn to a life that centers on the one who alone deserves all honor and worship. Any discussion of spirituality that is not attentive to God’s promise to complete his work through Christ can easily become a trap that ironically lures one away from the true worship of God.

To acknowledge the reality of the fulfillment of God’s promise in the future complete redemption of the body is to realize the need to be faithful in one’s present existence. The failure to affirm this objective reality leads to a false understanding of the significance of Christ’s death and resurrection. An example can be found in a recent treatment on spirituality that adopts an existential reading of the meaning of Christ in which dying to Christ is interpreted as death to an insistence of “a heterosexual orientation” and “a judgmental image of God,” while resurrection becomes the awakening “to a gay or lesbian identity, a God of unconditional love, or the realization that the church is a fallible and, at times, oppressive and damaging institution.”106 One wonders if this understanding of spirituality is precisely the kind that Paul is seeking to correct when he insists on the sovereignty of Christ, who is not only the liberator of the oppressed but the one who challenges all forces that distract one from conforming “to the image of their Creator” (v. 10). Moreover, the note on “the wrath of God” in v. 6 reminds one that the glorious Christ is also the holy God, who demands full obedience.

An eschatological spirituality is, therefore, not an escapist ideology that allows its followers to downplay the significance of the present, earthly existence. This point is already implicitly noted in the tension between the singular “Christ,” who is in heaven (v. 1), and the plural “things above,” on which one is supposed to focus (v. 2). These “things” are further explicated as Paul urges believers to lead a faithful life precisely because they are focused on the exalted Christ. For Paul, then, “believers should (to adapt a modern idiom) be so heavenly minded that they do more earthly good.”107

Finally, this critical eschatological spirituality unmasks all present imposters who claim to be the realization of God’s kingdom on earth. To identify the consummation of God’s work in the present age without sufficient attention to the glorious future can easily lead to “enslavement to current ideology, be it liberal democracy, feminism or green politics.”108 Since God is the one who brings about this new creation through Christ, he is the only one who can complete this new creative act when Christ returns in glory. To downplay the future only leads to a false perception of God’s work in the present age. Certainly, God works through the church to redeem people and incidentally culture today. Historically, however, some groups have attempted to inaugurate heaven on earth through ascetic communities or other cloisters. This self/human-generated attempt misses the point of Colossians. Paul emphasizes that the church must live in light of the accomplished new reality even though things are not yet consummated and physically perceptible. Paul is focused on right action in light of God’s work in Christ, not the bringing about a new kingdom on earth. Christ accomplished a new reality, and he alone will bring it to consummation.

Put to Death the Earthly Parts

In our previous discussion, we offered cautionary notes concerning the function of the ethical imperatives in Paul.109 In this section, however, one cannot ignore the clear and direct call to avoid certain vices. Without taking the two lists (vv. 5, 8) as comprehensive, they do sufficiently represent behaviors that betray one’s identity as God’s redeemed people. Both lists directly lend themselves to application, and numerous examples can be cited in bringing to life these vices.

The significance of the first list is noted with the final item linked with an explanatory phrase: “covetousness, which is idolatry” (v. 5). As noted in the exegetical discussion, this final note connects the list to the Ten Commandments. Lust and illicit sexual behavior are expressions of covetousness, which are considered to be idolatrous acts because of the displacement of God as the proper object of worship. Beyond marital infidelity and other immoral acts, contemporary readers should also be reminded that pornography, which is so prevalent among Christians and even clergy, does not simply involve a “two-dimensional artifact” but is itself “a series of activities” that reduces the person (often a woman) to a subordinate tool devoid of the dignity as one created in the image of God.110

Often considered as belonging to a different category, premarital sexual acts that glorify the supremacy of love often loom large in church youth programs, but a repressive strategy is often imposed without a proper positive focus on the need to divert one’s energy in the pleasure of worshiping God. Paul reminds us that the root of these vices lies in covetousness, which can be defined as “the loss of contentment in Christ so that we start to crave other things to satisfy the longings of our heart.”111 As sexual desires touch on the deepest cravings of one’s soul, their manifestation reflects whether one is able to lead a christocentric life through faith in God’s redemptive act in Christ. This in turn explains why sexual vices often appear in vice lists in Paul (Rom 1:26–27; 13:13; 1 Cor 5:10–11; Eph 5:3; 1 Tim 1:10).

In the second list (v. 8), one finds various forms of vices related to the untamed tongue. The connection with James 3 has already been established insofar as violent verbal acts are considered acts that contradict the confession of the lordship of Christ. Notes on anger and wrath (v. 8) in the context of a reference to “the image of their Creator” (v. 10) point to the relevance of a book that contains an intense focus on speech ethics (Jas 1:19, 26; 3:1–12; 4:11–12; 5:9, 12), and where speech is considered “the index of a person’s whole moral being.”112 In 3:9, James makes it clear that to insult a person is to insult the Creator in whose image the person had been created: “With the tongue we praise our Lord and Father, and with it we curse human beings, who have been made in God’s likeness.” To insult a person is therefore to take on the posture of the Creator, who alone has the right to judge his creation. Instead, believers are called to the humble worship of the Creator God—a point that is well made by Jeremy Taylor in the classic work, The Rule and Exercises of Holy Living and Holy Dying:

Humility is the most excellent natural cure for anger in the world; for he that by daily considering his own infirmities and failings makes the error of his neighbour or servant to be his own case, and remembers that he daily needs God’s pardon and his brother’s charity, will not be apt to rage at the levities, or misfortunes, or indiscretions, of another.113

In the context of Colossians, this vice list should also be understood in light of the repeated affirmation of the final authority of Christ. To be involved in violent speech acts is to refuse to submit to the lordship of Christ and is thus an idolatrous act. Moreover, as in James 3, where abusive speech is an act of denying the truth (Jas 3:14), Paul concludes the list with a call to acknowledge the truth in one’s daily living (v. 9). His exhortation is therefore one that centers on the integrity of faithful living that is consistent with the confession of believers.

Put on Christ, the New Uniform

In adopting the clothing metaphor with the call to “put … away” (v. 8) and “put on” (v. 10), Paul draws attention to the need to shed one’s identity and put on a common identity that conforms to the reality one finds in Christ. This uniformity, which results in the conformity to “the image of their Creator” (v. 10), creates a new social self within a community that is to be distinguished by nothing else but “Christ,” who is “all and in all” (v. 11).

The significant social and political implications are highlighted by Paul’s definition of the new humanity in communal terms: “where there is neither Greek nor Jew, circumcised nor uncircumcised, barbarian, Scythian, slave nor free” (v. 11). Although the Jews were not distinguished by their clothing, the Greeks and Romans did notice the distinct clothing practices of various people groups.114 To suggest that believers put on a distinct set of clothing is to call the believers to participate in a “communion of the different”115 as they distinguish themselves as those belonging to Christ alone.

The power of this clothing metaphor is well illustrated by a sociocultural analysis of clothing practices:

Clothing functions to indicate personal identities, social and cultural positions and roles. For example, garments worn may indicate that one is male, female, young, old, wealthy, poor, monarch, peasant, priest, minister, civilian, soldier, athlete, prisoner, judge, academic or many other things. A redressed person may be a re-formed or re-presented person, one who has a changed identity and a changed social role.116

Not only does the clothing of a person reflect on his or her social and political identity; the wearing of a specific type of clothing also aids in transforming the self-understanding of a person: “Constant wearing of official costume can so transform someone that it becomes difficult or impossible for him or her to react normally.”117 In the case of a uniform, when the entire community follows the same clothing practices, it transforms the individual’s personality into a social identity where one acts within the boundaries within a code of behavior dictated by the wider community.

In light of the significance of clothing practices, therefore, Paul’s use of the clothing metaphor takes on added significance. To outsiders, believers are to be identified as those belonging to Christ. To the believers, this act of adopting a new set of clothing will affect their behavioral pattern as they externalize their confession under the lordship of Christ. Though no longer unique within the group, this group is to be different from the rest of humanity as it transcends social, cultural, and ethnic barriers in testifying to the transformative power of the gospel of the cross.

In our times, communities of God’s believers still need to be called to witness this new social and cultural identity. It has been noted that “at 11:00 on Sunday morning when we stand and sing and Christ has no east or west, we stand at the most segregated hour in this nation.”118 In other parts of the world, similar observations can be made in Christian communities, whether it is the remnant of a colonial past or the result of more recent labor movements where different people groups converge in one locale.

Those preaching or teaching on this text may want to take the opportunity to encourage their audience to wrestle with ways in which the unity of God’s people can be lived out in their own contexts. The disunities are not exclusively racial as Paul indicates, and they often involve economic, educational, and social stratifications and biases imported from the larger culture. Some have attempted to merge different ethnic congregations,119 while other creative solutions may be more appropriate in different contexts.120 In any case, we are called to demonstrate our unity in Christ as one new humanity in concrete ways. This unity will testify to the power of the gospel message even in the present age.