Chapter 13

Philemon 8–16

Literary Context

In the previous section, which contains the opening greetings (vv. 1–3), thanksgiving (vv. 4–5), and prayer report (vv. 6–7), Paul paves the way for this central section, which contains his requests regarding Onesimus (vv. 8–10). The introductory section has provided the framework for Paul’s requests by identifying the various characters involved through their positions within the family of God. While God is “our Father” (v. 3) and Jesus Christ is the “Lord” (v. 3), Philemon is a “brother” (v. 7). This points ahead to Paul’s urging Philemon to receive Onesimus also as a “brother” (v. 16) in view of his new position as a believer, a “son” born to Paul during his imprisonment (v. 10).

The thanksgiving and prayer report also provide the foundation for Paul’s argument here. Paul’s thanksgiving is based on Philemon’s “love for all the saints” and “faith in the Lord Jesus” (v. 5). The prayer report likewise focuses on “faith” (v. 6) and “love” (v. 7) for one who claims to be a member of the household of God. In the letter body, “love” becomes the basis for Paul’s appeal to Philemon (v. 9).

Most scholars agree that the main body begins with v. 8. But there is no consensus as to where it ends and whether a discernible division can be found within this body. This lack of consensus is due to the close connection between vv. 8–16 and vv. 17–20 on the one hand, and the presence of further instructions in vv. 21–22 on the other.

We should begin with the ending of the main body. Because it obviously focuses on Paul’s appeal to and instructions for Philemon, some see a distinct break at the end of v. 22 (cf. GNB, CEV, NEB, HCSB, NET, NLT, ESV).1 This is supported by the presence of a final instruction (to provide a guest room for Paul) in v. 22, while v. 23 shifts to the greetings. Those who consider the main body as focusing on the issue surrounding Onesimus see v. 21 as providing a natural break, for there Paul concludes with a final admonition to Philemon to be obedient to what is asked of him (cf. NRSV, NJB, TNIV, NIV).2 Finally, for those who consider v. 21 as a concluding note that underlines the urgency for the main body of the letter, v. 20 becomes the natural conclusion to the main body (cf. NAB).3

The consideration of vv. 8–20 as containing the main body of the letter provides the best reading. First, the phrase “at the same time” (ἅμα δέ) at the beginning of v. 22 links this verse with v. 21. Since v. 22 deals with Paul’s travel plan, it fits well within the closing section of Paul’s letters (cf. Rom 15:22–32). Thus, it is best to see v. 21 as the beginning of the closing section. Second, the words “brother” (ἀδελφέ), “refresh” (ἀνάπαυσον), and “heart(s)” (τὰ σπλάγχνα), which conclude the introductory paragraph (v. 7), reappear in v. 20; they provide a corresponding conclusion to this second section of the letter.

The line between the two subsections within the main body of the letter is even less clear.4 Our division points to the first subsection as providing Paul’s appeal on the basis of his relationship with Onesimus (vv. 8–16), while the second one provides the instructions on the basis of his relationship with Philemon (vv. 17–20). This division is suggested by the absence of imperatives in vv. 8–16 but the presence of the verb “appeal” (παρακαλῶ) in vv. 9, 10; by contrast, vv. 17–20 contain three imperatives (vv. 17, 18, 20). The presence of “therefore” (διό) in v. 8 and a comparable marker (οὖν) in v. 17 further confirms these two subsections.5

In vv. 8–16, Paul evokes his authority (v. 8), though basing his appeals on love (v. 9). He also alludes to his relationship with Onesimus (v. 10), Onesimus’s usefulness for him (v. 11–14), and his new relationship in Christ and thus his place in Paul’s heart (v. 15–16). With such appeals, Paul provides specific instructions in vv. 17–20 for Philemon to receive Onesimus and thus refresh Paul’s heart.

- I. Opening Greetings (vv. 1–3)

- II. Faith and Love (vv. 4–7)

- III. Requests concerning Onesimus (vv. 8–20)

- A. Appeals from the Relationship between Paul and Onesimus (vv. 8–16)

- B. Instructions from the Relationship between Paul and Philemon (vv. 17–20)

- IV. Final Greetings (vv. 21–25)

Main Idea

Identifying Onesimus as his child and as one useful for him and the gospel ministry, Paul urges Philemon to consider him no longer as a slave but as a beloved brother. This new sense of reality provides the basis for Paul’s explicit instructions in the section that follows.

Translation

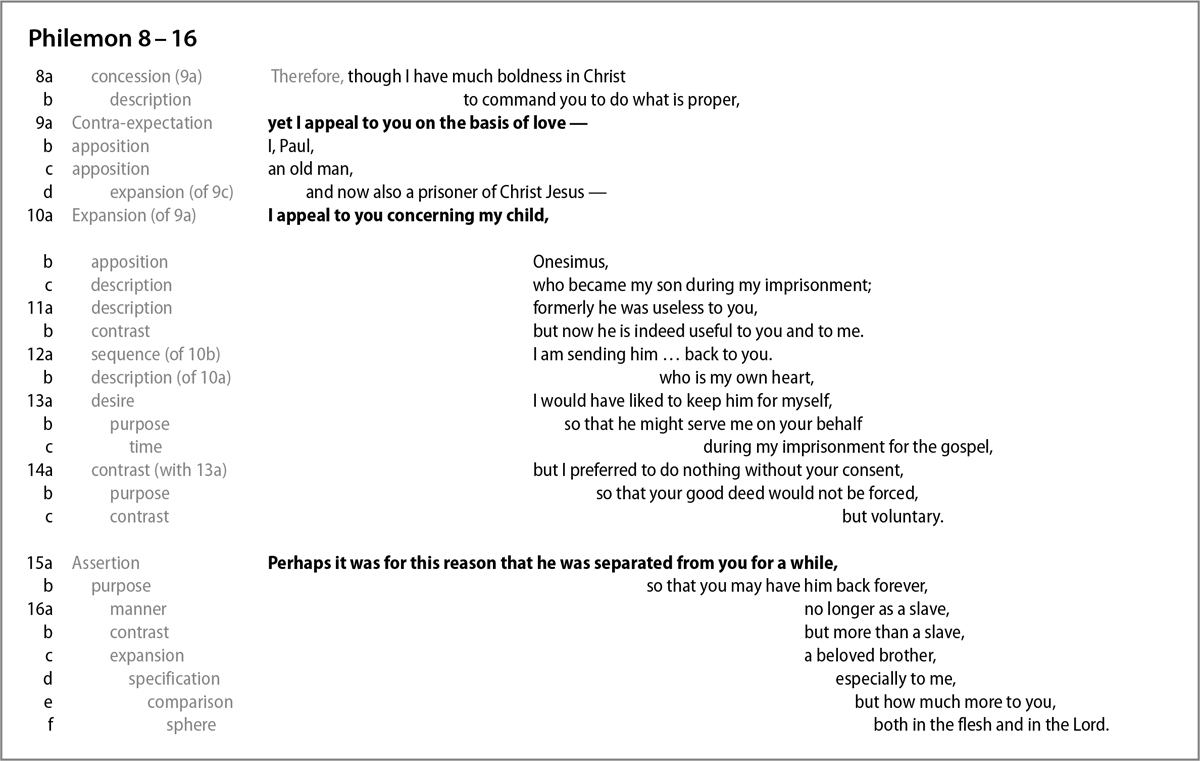

Structure

Paul appeals to Philemon on the basis of Paul’s relationship with Onesimus. He begins by noting his authority over Philemon, but then expresses his decision to appeal to Philemon on the basis of love instead (v. 9a). Therefore, he does not identify himself as an apostle, but as a prisoner and an old man (v. 9b-d). Although this is an appeal of love, such a self-identification does carry sufficient rhetorical force to fuel the particular appeal that follows.

In v. 10 Paul begins his appeal by identifying Onesimus as his “child,” one born to him in his imprisonment. This father-son relationship transforms the requests that follow into ones that cannot be rejected. Playing on the meaning of his name, Paul describes Onesimus as someone who is “useful” to him, although he might not have been so to Philemon (v. 11). In describing his decision to send Onesimus back to Philemon, Paul further identifies Onesimus as his “heart” (v. 12). He then expresses his desire to keep Onesimus for himself so that he can serve Paul and thus also further the cause of the gospel on account of which Paul is imprisoned (v. 13). Echoing his earlier sentiment concerning love as the basis of his appeal (cf. v. 10), Paul reiterates his desire not to force Philemon into submission, but to encourage him to respond according to his own will (v. 14).

In the third sentence of this section, through the use of a divine passive (“he was separated,” ἐχωρίσθη, v. 15), Paul notes a possible explanation of the divine will behind the separation between Philemon and Onesimus, with an implicit appeal that Philemon should receive Onesimus back “no longer as a slave, but more than a slave, a beloved brother” (v. 16a-c).6 Even here, Paul calls Onesimus his “beloved brother” and urges Philemon to share this view (v. 16d-e). This paragraph shifts the attention away from the personal relationship between Paul and Onesimus to the relationship between God and Philemon.7 These references to God frame this appeal to consider Onesimus as a “beloved brother,” one that can be considered the climax of Paul’s appeal in this letter.

Exegetical Outline

- I. Appeals from the Relationship between Paul and Onesimus (vv. 8–16)

- A. Based on love rather than on authority (vv. 8–9)

- B. Onesimus as Paul’s child (v. 10)

- C. Onesimus as useful to Paul (v. 11)

- D. Onesimus as Paul’s heart (v. 12)

- E. Paul’sdesire to keep Onesimus (vv. 13–14)

- F. Reference to divine purpose (vv. 15–16)

- 1. Onesimus to be received as Philemon’s brother (vv. 15–16c)

- 2. Onesimus as Paul’s beloved brother (v. 16d-f)

Explanation of the Text

8 Therefore, though I have much boldness in Christ to command you to do what is proper (Διό, πολλὴν ἐν Χριστῷ παρρησίαν ἔχων ἐπιτάσσειν σοι τὸ ἀνῆκον). Paul implicitly establishes his authority by claiming he will not evoke such authority. “Therefore” (διό)8 signals the beginning of a new section. The comma after this conjunction and the one at the end of this verse reflect an exegetical decision to connect this adverb with the verb that appears in the next verse, thus: “therefore … I appeal to you.”9 In this context, the conjunction points back to v. 7 as the grounds of Paul’s appeal: “because the hearts of the saints have been refreshed through you in the past, I am appealing to you….” But v. 7 is part of the wider discussion of faith and love in vv. 4–7. Since those verses introduce Paul’s central appeal in this letter body, it is best to see this conjunction as pointing back to the entire thanksgiving and prayer report.

The participle “though I have” (ἔχων) is a concessive circumstantial participle. The word “boldness” (παρρησίαν) can carry overlapping layers of meanings. It can refer to the “public” (Mark 8:32; John 7:4, 13, 26; 11:54) and “plain” (John 11:14; 16:25, 29) nature of one’s expressions. It can also refer to “confidence” (Acts 2:29; 2 Cor 7:4; Heb 10:35) and “boldness” (Acts 4:29, 31; 28:31; Phil 1:20; 2 Cor 3:12; Eph 3:12) that is built on one’s relative position of power and authority. In this context, most readings affirm the unique authority derived from Paul’s relationship with and position “in Christ.” For those who translate this term as “freedom,” it points to “the capability to speak up freely” because the Lord “enables them to open their mouths freely and courageously.”10 For those who adopt the translation “confidence”11 or “boldness,”12 it is a confidence derived from the authority of Christ rather than one that is based on one’s inherent rights.

This “boldness” grounded “in Christ” can refer to the “boldness” that believers experience in the victory of Christ (Phil 1:20; 1 Tim 3:13; cf. Col 2:15). Here, however, when it is used with the verb “command” (ἐπιτάσσειν), Paul is clearly pointing to his unique authority over Philemon.13 This “boldness” can then be understood as “apostolic παρρησία,”14 one derived from his position as an “apostle of Christ Jesus by the will of God,” a self-identification often found at the beginning of his letters (1 Cor 1:1; 2 Cor 1:1; Eph 1:1; Col 1:1; 2 Tim 1:1).

Significantly, elsewhere in his letters Paul never refers to his own exercise of his authority “to command.”15 Using the nominal form (“command,” ἐπιταγή), more than once he expresses his hesitancy to command believers (cf. 1 Cor 7:6; 2 Cor 8:8), probably because of his conviction that only God can command (Rom 16:26; 1 Cor 7:25; 1 Tim 1:1).16 It is striking, therefore, to find Paul affirming that authority here. Even though he claims not to use such power, the mere mentioning of such authority is in itself a striking power claim. It has been rightly noted, therefore, that in this verse “Paul parades a theoretical apostolic authority unmatched elsewhere in his letters.”17 Moreover, the expectation that Philemon will respond “in obedience” (v. 21) assumes that Paul is engaging in the exercise of his apostolic authority.18

Regarding “what is proper” (τὸ ἀνῆκον), the context implies a sense of duty, which is made explicit in some versions: “what is required” (ESV) and “your duty” (NRSV). Paul does not specify the basis for determining what is proper. It is possible that he is referring to the appeals that follow, thus: “what you ought to do according to the content of this letter.” Nevertheless, in light of the reference to Paul’s authority “in Christ,” it seems best to consider the reference to be in the wider sense of proper behavior in Christ, thus: “that which is proper for one who lives under the authority of Christ.” The phrase “as is fitting in the Lord” in Col 3:18 provides additional support for this reading.

9a Yet I appeal to you on the basis of love (διὰ τὴν ἀγάπην μᾶλλον παρακαλῶ). Instead of “command,” Paul appeals to Philemon in love. “I appeal” (παρακαλῶ) implies making a request,19 but it is a request made with strong emotional investment.20 In contrast to “command,” “appeal” points to a different framework of relationships within which the interaction between Paul and Philemon is to be defined. “Command” reflects a relationship between two official parties with different social and political locations; “appeal” is a request made within the sphere of personal friendship. Paul, therefore, is arguing against the use of authority based on hierarchical structure and turning to a frame of reference derived ultimately from their individual relationships with Christ. Moreover, this “appeal” becomes an example for Philemon’s own interaction with his slave: “Paul used conventions of brotherhood to appeal to Philemon to treat a runaway slave as a brother rather than a criminal.”21

Despite the contrast between “command” and “appeal,” Paul has clearly established his authority to call Philemon to obedient submission. But the focus on “appeal” points to a different use of power as Paul seeks to challenge the rhetoric of “domination and control” while seeking to emphasize the transformative power embedded in the gospel message of Jesus as Lord (cf. vv. 3, 5, 16, 20, 25).22 It is the authority of this message that undergirds Paul’s rhetoric.

As “the basis” (διά + accusative) of Paul’s appeal, this “love” does not refer to his mode of appealing, but to the grounds of this appeal in Philemon’s own prior acts of love.23 If Paul were focusing on his own mode of appealing, he would have used διά + genitive, as he did elsewhere: “I appeal to you, brothers and sisters, by our Lord Jesus Christ and by the love of the Spirit” (Rom 15:30 NRSV). Here the emphasis on “love” as the basis of Paul’s appeal continues the theme already mentioned in the introductory section (vv. 5, 7). That basis lies, therefore, within Philemon’s own expression that grows out of his faith in the Lord Jesus Christ rather than in the external authority imposed by the apostle Paul.

9b-d I, Paul, an old man, and now also a prisoner of Christ Jesus (τοιοῦτος ὢν ὡς Παῦλος πρεσβύτης, νυνὶ δὲ καὶ δέσμιος Χριστοῦ Ἰησοῦ). Shifting from Philemon’s prior acts of love, Paul now reflects on his own circumstances. The participle left untranslated here (ὤν) has been variously understood as causal (“since”) or concessive (“even though”). The decision rests on whether the word πρεσβύτης is to be taken in a positive (“ambassador”) or negative (“old man”) sense, thus: “since I am … the aged” (NASB), or “even though I am … the ambassador of Christ Jesus” (GNB). Our translation aligns with those who consider this clause as a parenthetical clause syntactically separated from the previous clause (NRSV, NLT, NET, ESV); the repetition of “I appeal” (παρακαλῶ) in v. 10a resumes the thought begun in v. 9a.

Because of the difficulties in understanding why Paul here, and nowhere else, identifies himself as an “old man,”24 some have suggested it means “an ambassador” (cf. 2 Cor 5:20; Eph 6:20). Those who argue for this reading point to a number of factors:25 (1) elsewhere Paul identifies himself as “an ambassador in chains” (πρεσβεύω ἐν ἁλύσει, Eph 6:20); (2) the word “ambassador” (πρεσβυετής) is only one letter different from “old man” (πρεσβύτης), and the reading in our present Greek text may reflect an early corruption of the text; (3) even if not, one can point to several documents where πρεσβύτης is used instead of πρεσβευτής for an ambassador (e.g., 1 Macc 13:21; 14:22), probably because of a confusion between these words.

The majority of the contemporary versions26 and a number of commentators continue to consider “old man” the correct reading.27 First, the lexical support for “ambassador” is weak, and the few references likely point to scribal errors.28 Second, there is no manuscript support for “ambassador” (πρεσβευτής) here. Third, since Paul has just given up a rhetoric of power (v. 8), it would be surprising to find him reverting to a label such as “ambassador.”29

In Paul’s argument, “old man” fits the context well since both “old man” and “prisoner” point to experiences of dependence and weakness.30 Here, “Paul begins his argument to Philemon by evoking considerable pathos for himself—as an old man and prisoner in need of support—and at the same time by establishing Onesimus’ ethos—as his child who is now responsible for his support.”31 Shifting from a rhetoric of power to one of weakness, Paul urges Philemon to consider his relationship with Onesimus within this new frame of reference.

Paul’s self-identification as a “prisoner of Christ Jesus” builds on this sense of dependence and weakness and pushes his point one step forward. While being an “old man” is the natural stage in one’s life journey, being a “prisoner of Christ Jesus” reflects an obedient will that has responded to the divine call.32 Here, Paul is likewise calling Philemon to submit to the divine will in giving up his own sense of autonomy and superiority. Elsewhere, Paul also calls others to join him “in suffering for the gospel” while identifying himself as “his [the Lord’s] prisoner” (2 Tim 1:8).

10 I appeal to you concerning my child, Onesimus, who became my son during my imprisonment (παρακαλῶ σε περὶ τοῦ ἐμοῦ τέκνου, ὃν ἐγέννησα ἐν τοῖς δεσμοῖς Ὀνήσιμον). Paul now gives the content of his appeal by mentioning of the name of the person who is its center. In the previous verse, “I appeal” (παρακαλῶ) is left without an object.33 An object does appear, however, in this verse: “I appeal to you [σε].” This points to Paul’s resumption of thought started at the beginning of v. 9, and the intervening material must be considered as parenthetical.

The preposition “concerning” (περί) used with the verb “I appeal” is unusual, and it lies at the center of a debate about the background and purpose of this letter. Although many versions read “I appeal to you for my son/child” (KJV, ASV, NASB, NKJV, NRSV, HCSB, ESV, TNIV, NIV), the meaning of “for” in these translations appears to have the sense of “on behalf of” (NAB, GNB), a reading adopted by most commentators.34 A few have, however, suggested that this preposition points to Onesimus as the object of the appeal: “I ask for [him].”35 Those who support this reading note that “to request on behalf of” would be represented by a different Greek phrase: παρακαλῶ ὑπέρ (cf. 2 Cor 5:20; 2 Cor 12:8; 1 Thess 3:2).36 But those defending the traditional reading point to papyri evidence that supports the reading of this preposition in the sense of “on behalf of.”37 Moreover, as with 1 Thess 3:2, there is a significant semantic overlap between the two prepositions.38

It should be noted, however, that these defenses merely point to the possibility of reading this phrase in the sense of “I appeal on behalf of”; they do not prove this is the more prevalent or even the only possible reading. The use of περί with this verb appears often in summons formulae in the papyri material,39 and one simply cannot rule out the possibility that Paul is using that same formula in the sense of “I ask for.” In short, while Paul is clearly appealing “concerning” Onesimus, it is unclear whether he is appealing “on behalf of” him (seeing this letter primarily as one that asks for forgiveness) or “for” him (seeing this letter as a request to have Onesimus returned to himself, cf. v. 13). The preposition, by itself, is not determinative enough to exclude or confirm either reading.

Paul identifies Onesimus as “my child” (τοῦ ἐμοῦ τέκνου)—an identification that also applies to Timothy (1 Cor 4:17; Phil 2:22). In both cases, “Paul is commending to the addressees a person coming to them from him.”40 In such contexts, this appellation takes on considerable rhetorical force because their relationships with Paul impose a certain demand on the recipients as they consider ways to receive them. This relationship is made explicit in the words that follow, where the relationship between Paul and Onesimus is depicted as a father-son relationship.

In this verse, we finally encounter the name of the person at the center of Paul’s discussion, Onesimus (Ὀνήσιμον).41 A common name applied to slaves,42 this “Onesimus” is likely the Onesimus whom Paul depicts as “the faithful and beloved brother” in Col 4:9. After identifying him as his “child,” Paul further describes him as the one “who became my son during my imprisonment.” This relative clause literally reads, “whom I have begotten in my imprisonment” (NASB). This is often taken to refer to Onesimus’s conversion,43 which reflects the OT tradition that considers a slave as a proper member of the household (cf. Gen 17:9–14).44 In the Jewish tradition, a convert is compared to a “child just born” (b. Yebam. 22a) since the son is to learn the Torah from his own father.45

Because of this relationship, one can conceivably understand this metaphor as extending beyond the time of conversion. In Phil 2:22, for example, Timothy is identified as Paul’s son because of his involvement in Paul’s ministry: “you know that Timothy has proved himself, because as a son with his father he has served with me in the work of the gospel.” It is therefore possible to see this metaphor as referring to “some other kind of changed relationship.”46 Others have hypothesized that Onesimus would have been “converted” in a more general sense when Philemon’s household became part of the wider Christian community, and the present reference to his birth points to “the reincorporation of Onesimus into Christian fellowship.”47 In any case, the relationship between Paul and Onesimus is underlined with this reference, and its rhetorical force cannot be missed.

11 Formerly he was useless to you, but now he is indeed useful to you and to me (τόν ποτέ σοι ἄχρηστον νυνὶ δὲ [καὶ] σοὶ καὶ ἐμοὶ εὔχρηστον). Playing on the meaning of Onesimus’s name, Paul points to his new status and function within the ministry of the gospel. In Greek, this verse is not a separate sentence but a further description of Onesimus: “who formerly was useless to you, but now is useful both to you and to me” (NASB). This text immediately follows the name “Onesimus,” a name that means “useful.”48 This wordplay provides a contrast between Onesimus’s past and his present status as a true believer. The pair, “useless” (ἄχρηστον) and “useful” (εὔχρηστον) has also been translated as “unprofitable” and “profitable” (cf. KJV, ASV, NKJV). Paul does not specify in what ways Onesimus has been “useless” to Philemon. Some suggest it refers to Onesimus’s escape from his master,49 while others point to the wrong he had done to Philemon (as perhaps implied in v. 18),50 or simply the general unreliability of his work.51

It should be noted, however, that this contrastive pair built on the meaning of the name Onesimus does not necessarily have to point to a reality behind both elements in the pair. If Paul is focusing on the usefulness of Onesimus, “ἄχρηστον need not function literally outside the word play.”52 Moreover, it has been noted that Phrygian slaves were notorious for their “vulgar type of slavish offenses.”53 Paul may be simply alluding to such a reputation while emphasizing the present usefulness of Onesimus. Others have suggested this uselessness may well refer to Onesimus’s past as an unbeliever. As in the case of all human beings, only through God’s grace can one find oneself useful in the plan of God.54

In any case, it is at least possible that this contrast between “useless” and “useful” aims primarily at highlighting the usefulness of Onesimus in the gospel ministry now that he is a Christian disciple.55 The reference in v. 13 that Paul would like to keep him for his service may further support this reading. This focus on Onesimus’s present usefulness rather than his past uselessness is specifically noted with the use of the word “indeed” (καί) here.56

With this understanding of this wordplay, one may also be able to explain the phrase “to you and to me” (σοὶ καὶ ἐμοί). These two pronouns may point again to Paul and Philemon’s partnership in faith (cf. vv. 6, 17).57 In Col 4:9, Paul has already identified Onesimus as a “faithful” brother. Here, with the common ground in the gospel message, Paul may be implying that Philemon should continue to have Onesimus serve in some ways for the advancement of the gospel. Less likely is the possibility that Paul is referring to Onesimus’s present usefulness to him in the gospel ministry, but his usefulness to Philemon as a slave after his return.

Beyond the wordplay on Onesimus, many also see a play on the word “Christ” (Χριστός) and a related word for “useful” (χρηστός), since both words were pronounced the same in Hellenistic Greek.58 This wordplay fits the context well, but if this secondary wordplay is present, one would have expected Paul to use the word χρηστόν instead of εὔχρηστον for “useful” here. This wordplay seems to be less than obvious.

12 I am sending him, who is my own heart, back to you (ὃν ἀνέπεμψά σοι, αὐτόν, τοῦτ’ ἔστιν τὰ ἐμὰ σπλάγχνα). As Paul comments on Onesimus’s return to Philemon, he again emphasizes Onesimus’s importance to him. As with vv. 10b–11, this verse is actually a relative clause in Greek, providing further description of Onesimus: “whom I am sending back to you, him, who is my own heart.”

This verse has a complicated textual history, prompted by the appearance of the relative pronoun (“whom,” ὅν) with the seemingly redundant third person pronoun (“him,” αὐτόν), thus, literally: “whom I am sending back to you, him, who is my own heart.” The reading chosen here has been considered to be one that “best explains the origin of the other readings.”59 The awkward presence of αὐτόν may emphasize Onesimus as the proper subject of the discussion without explicitly naming him,60 and the absence of any imperative here may aim at suspending the expectation of the readers until v. 17, where the proper appeal is made when Paul again identifies Onesimus with his own self: “receive him, as you would receive me.”

Almost all contemporary versions take the verb ἀνέπεμψα to mean: “I am sending … back.”61 Noting the frequent use of this verb in the NT in the sense of “referring or remitting a case,” however, some have suggested the translation “I am sending up.”62 The verse then takes on a legal sense: “It is this new Onesimus—Onesimus really himself—whose case I am referring to you [ἀνέπεμψα], and now that I send him, I seem to be sending my heart.”63 While this reading may again challenge the traditional reading, some who affirm the traditional hypothesis—which sees Onesimus as a runaway slave and the letter as a letter appealing for forgiveness—consider “I am sending up” as an appropriate translation.64 It is true that this legal meaning was a common one in ancient documents, but “sending back” is “the alternative meaning” in the Hellenistic papyri documents,65 and it fits the context better.

The word “heart” reappears here (cf. v. 7) as Paul identifies Onesimus as “my own heart” (τὰ ἐμὰ σπλάγχνα). This phrase can justifiably be taken as “a part of myself” (HCSB). Paul is sending his own self to Philemon, and he expects Onesimus to be treated as such (v. 17).66 Moreover, to describe a slave as “my own heart” identifies him within the new frame of reference in Christ. This identification serves to force Philemon to accept Onesimus’s new status. After all, to accept this “heart” would demonstrate Philemon’s continued commitment in his labor of love for all the saints (v. 7), as well as his partnership with Paul (vv. 17, 20).

13 I would have liked to keep him for myself, so that he might serve me on your behalf during my imprisonment for the gospel (ὃν ἐγὼ ἐβουλόμην πρὸς ἐμαυτὸν κατέχειν, ἵνα ὑπὲρ σοῦ μοι διακονῇ ἐν τοῖς δεσμοῖς τοῦ εὐαγγελίου). As Paul provides further description of Onesimus, he alludes to his possible future service for Paul himself and for the gospel. In Greek, this relative clause focuses on Onesimus, who is at the center of Paul’s desire in his service for the gospel: “whom I wished to keep with me, so that …” (NASB).

The emphatic first person pronoun “I” (ἐγώ) draws attention to Paul’s own desire and sets up a contrast between that desire and his decision to do what is appropriate under the circumstances: thus, “I really wanted to …” (NLT). The imperfect verb “I would have liked to” (ἐβουλόμην) is to be read with the aorist verb “I preferred” (ἠθέλησα) in the next verse. The change in the vocabulary and tense is important. In this context, “the imperfect implies a tentative, inchoate process; while the aorist describes a definite and complete act.”67 The imperfect can therefore be translated as an unfulfilled wish: “I would have liked to …” (NIV; cf. ESV),68 while the aorist as a definitive act: “I preferred …” (NRSV). In terms of meaning, there is significant overlapping in the semantic domains of the two verbs, both being used to express “desire, want, wish.”69 If a distinction is to be made, “I would have liked to” denotes Paul’s own “desire,” while “I preferred” denotes his “will” or “resolution.”70 Taken together, Paul is suppressing his own desire in his own resolution to do what is appropriate.

In the previous verse, Paul has already noted he is sending Onesimus back to Philemon. Here he expresses his own desire to do the opposite, and in the next, he explains why he made the decision that he did. The discrepancy between Paul’s own desires and his final decision has led some to read the infinitive “to keep” (κατέχειν) as “implying … that it was Onesimus who was anxious to return to make amends and peace with his master.”71 Others point to the possibility that “the congregation living in the city of Paul’s captivity may have exerted some pressure on Paul, advising that he separate himself from the fugitive, who had been harbored long enough.”72 These readings not only assume a particular background behind the separation of Philemon and Onesimus, but they also attribute Paul’s decision to external factors. What Paul himself emphasizes, however, is his own will to send Onesimus back, perhaps in order to maintain “partnership” with Philemon (vv. 6, 17). It is precisely this “partnership” that forms the basis of his argument.

The reason for Paul’s desire to keep Onesimus is that “he might serve” (διακονῇ) him in his imprisonment. In Paul’s letters, the verb διακονέω is always used in a religious/theological context. Therefore, it seems probable that Paul is expressing his desire to have Onesimus serve as a minister of the gospel.73 The fact that serving Paul is serving the gospel is made clear by the reference to his “imprisonment for the gospel”; his predicament is part of his calling as one who serves the gospel mission. Some even consider this verse as the heart of Paul’s appeal as he expresses his desire to have Onesimus serve as a gospel missionary.74 The presence of this implicit appeal with the absence of any note on Onesimus’s repentance forces one to reevaluate the background and thus the purpose of this letter. Instead of an appeal for forgiveness, the focus on Onesimus’s usefulness (v. 11) and the expression of Paul’s desire to have Onesimus “serve” in the gospel ministry point to this wider ministerial and evangelistic concern as lying at the center of this letter.

The phrase “on your behalf” (ὑπὲρ σοῦ) may be important in more than one way. First, if Onesimus had been sent by Philemon to serve Paul in prison, this presupposition would assume this fact and suggest that Philemon should permanently release Onesimus so that this brother can continue to serve Paul on his behalf. Moreover, the need for Philemon to serve Paul in some ways may assume a certain indebtedness on Philemon’s part. This assumption reemerges in v. 19, where Paul reminds Philemon that he owes Paul his very self. If so, the appearance of “on your behalf” also adds rhetorical force to Paul’s argument in this letter.

“During my imprisonment for the gospel” takes this prepositional phrase as a description of Paul’s own imprisonment. Less likely is that this refers to Onesimus’s future imprisonment as he serves in the gospel mission: “In the chains of the gospel he could serve me.”75 That this refers to Paul’s own imprisonment is supported by the fact that every appearance of the word “chain/imprisonment” (δεσμός) in Paul’s letters refers to his own imprisonment (Phil 1:7, 13, 14, 17; Col 4:18; 2 Tim 2:9; cf. Phlm 10). The genitival phrase “for the gospel” (τοῦ εὐαγγελίου) should be taken as a genitive of reference, expressing both the cause and the purpose of his imprisonment: “for the sake of the gospel” (NET; cf. GNB).76 What is not clear is whether “gospel” refers to the content of the gospel77 or the act of preaching the gospel. Verse 9 (“a prisoner of Christ Jesus”) points to the former reading, although both may be implied here.

14a But I preferred to do nothing without your consent (χωρὶς δὲ τῆς σῆς γνώμης οὐδὲν ἠθέλησα ποιῆσαι). As the final part of this long sentence, this verse serves as a transition from Onesimus as the center of concern to Philemon.78 Paul wants Philemon to respond voluntarily to his appeal.

This verse also serves as a contrast to the previous clause. This contrast is highlighted not only by the adversative conjunction “but” (δέ), but also by the presence of the emphatic “your” (σῆς), a stronger possessive pronoun instead of the simple genitival form of the second person singular pronoun (σου, v. 13).79 This pronoun corresponds to the emphatic first person pronoun “I” (ἐγώ) in the previous verse. The point is clear: despite Paul’s own desire, he is willing to give up his rights in honor of Philemon’s own judgment. Paul is thereby hoping that Philemon will give up his own rights to act in line with the new reality that exists in Christ.

The significance of “I preferred to” (ἠθέλησα), has already been noted in our discussion of v. 13. The translation adopted here (“I preferred to do nothing”), rather than the more idiomatic paraphrase, “I did not want to do anything” (NASB, NAB, REB, TNIV, NET, NIV; cf. HCSB, NLT), highlights the contrast with v. 13 and thus with Paul’s own act according to the strength of his will and conviction.

The meaning “consent” for γνώμη is common in Hellenistic writings.80 Behind Paul’s request for Philemon’s consent may lie the recognition that he is the rightful “master” of Onesimus;81 others point to Paul’s personal relationship with Philemon as the primary motivation behind this request.82 But in light of Paul’s attempt to convince Philemon to act within the new framework of the reality in Christ, it is best to see again Paul’s partnership (cf. v. 6, 17) with his coworker in faith (v. 1) as the primary force that will restrain him from simply exercising his rights according to his own personal desire.

14b-c So that your good deed would not be forced, but voluntary (ἵνα μὴ ὡς κατὰ ἀνάγκην τὸ ἀγαθόν σου ᾖ ἀλλὰ κατὰ ἑκούσιον). Paul now appeals to Philemon’s commitment to be consistent in his Christian walk. For the sake of contemporary readers, it is tempting to translate this “good deed” (τὸ ἀγαθόν) as “favor” (TNIV, NIV) or even with the verb “to help (me)” (GNB, NLT), but this translation is inadequate. This “good thing” refers to “every good thing” (παντὸς ἀγαθοῦ) in v. 6. There the “good thing” is described as that which “is in us for Christ.” The “good thing” is not limited to kind deeds performed for others; rather, it is that which is appropriate when one lives in Christ. In this context, therefore, Paul is not simply referring to a “favor” that Philemon should be doing for him, nor is he simply asking for Philemon’s help; he is instead trying to have Philemon live out the reality that he is already affirming: the new life lived out in the household of God.

With this reference to the “good thing,” one again confronts the question concerning the implied request embedded here. In light of v. 13, it seems best to consider this “good thing” as the release of Onesimus to serve Paul as he himself serves the Lord in his imprisonment.83 Those who consider this a “general expression which does not restrict the letter’s recipient to the fulfillment of a precise instruction”84 fail to recognize the importance of the previous verse in interpreting this phrase.

“Forced” (ἀνάγκην) carries the sense of “necessity” (KJV, ASV) and “compulsion” (NASB, NKJV, NET, ESV). In 1 Cor 7:37, this word is used in contrast to the one who “has control over his own will” (NIV). This is also how the term “voluntary” (ἑκούσιον) is to be understood. For readers familiar with the translation “spontaneous,”85 it should be noted this word is to be understood as “the opposite not of ‘premeditated’ but of ‘unwilling.’ ”86

It is no accident that Paul discusses this contrast between “forced” and “voluntary” in a letter that deals with the proper treatment of a slave. In setting up an example for Philemon, Paul has decided to grant him the freedom to act according to his own will in light of their partnership in Christ and the new reality found in Christ (cf. v. 15). As he does so, Philemon should similarly allow Onesimus to respond to the call to service according to his own will, and not according to the compulsion imposed on him by one who insists on his status as a slave. In addition to enhancing the rhetorical force of his argument, this verse is significant in that Paul is living out a model that Philemon is to follow.

15a Perhaps it was for this reason that he was separated from you for a while (τάχα γὰρ διὰ τοῦτο ἐχωρίσθη πρὸς ὥραν). Paul finally alludes to Onesimus’s separation from Philemon, and he considers this separation to be part of God’s will. The postpositive γάρ, left untranslated here (cf. “For perhaps it was for this reason,” NET),87 points to the syntactical relationship between vv. 15–16 and the previous sentence: Paul is sending Onesimus back although he wanted to keep him because of the possibility that Philemon and Onesimus would be able to relate to one another within the new framework in the household of God in Christ.

“For this reason” (διὰ τοῦτο) points ahead to the second half of the verse, which provides the reason for Onesimus’s temporary absence from Philemon. This is made explicit in some versions: “Perhaps the reason he was separated from you for a little while was that you might have him back forever.”88 This phrase is then connected with the “so that” (ἵνα) that follows, a clause that indicates this reason. Onesimus’s temporary absence from Philemon, then, becomes the reason for God to work so that the relationship between Philemon and Onesimus can be transformed permanently.

In terms of function, both “perhaps” and “he was separated” carry considerable theological weight. In this context, “perhaps” (τάχα), “a marker expressing contingency,”89 does not express doubt or uncertainty; rather, it calls for further deliberation and the need to see beyond what is apparent. Many, therefore, see this word as introducing “a cautious added thought,”90 while others suggest it points to “divine involvement.”91 In any case, these two verses aim at forcing Philemon to see the events that have transpired through the eyes of faith.

In the same way, “he was separated” (ἐχωρίσθη) should be taken as implying divine involvement. This passive verb is rightly considered to be a “divine passive,” so that God is the ultimate subject of what took place.92 Some have considered this verb as a “euphemistic verb,”93 and Paul’s use of it shows that he “clearly does not want Philemon to be reminded of the damage he has suffered.”94 Others have suggested that by using this verb, Paul intends “to protect Onesimus yet also give his master a precise hint of Onesimus’s crime.”95

These inferences are, however, without basis. Consistent with other Hellenistic uses, in the NT this verb occurs in reference to the departure from a locality (Acts 1:4; 18:1,2), separation from objects/persons (Rom 8:35–39; Heb 7:26), and also the extended meaning as in discussions of divorce (Matt 19:6; Mark 10:9; 1 Cor 7:10, 11, 15). In ancient documents, it does not refer to an escape, nor is it a euphemism for a criminal act. From this verb, therefore, one cannot argue for the presence of a criminal act that prompted this separation.96

It is best to see God as the focus of this verb. Paul is using it to suggest that God might have used him in his meeting with Onesimus as an instrument for a higher end: to convert Onesimus into a believer and a disciple. He has been brought into a network of relationships in which all are full members and siblings within the household of God. For Philemon, to receive Onesimus back “represents the completion of God’s design.”97

15b So that you may have him back forever (ἵνα αἰώνιον αὐτὸν ἀπέχῃς). As noted above, this clause provides the content of the prepositional phrase “for this reason,” for Paul considers it God’s will for Philemon to accept Onesimus as a fellow believer. “You may have … back” (ἀπέχῃς) can acquire a technical sense of “receiving full payment” in business transactions (cf. Phil 4:18),98 but here it refers to the full and willing reception of Onesimus.

The contrast with the previous clause is highlighted by word order. The previous clause ends with “for a while” (lit., “for an hour,” πρὸς ὥραν), while in this clause “forever” (αἰώνιον) immediately follows the conjunction “so that” (ἵνα). The temporary separation will now be overshadowed by a renewed relationship that lasts “forever”; this renewed relationship is the focus of the next verse. Here, “forever” likely means “permanently” (HCSB).

The use of “forever” may evoke a similar use in Exod 21:6, where a voluntary slave would have his ear pierced and would “be his [master’s] servant for life [εἰς τὸν αἰῶνα].”99 But in light of the next clause, where Paul clearly states that Philemon is to receive Onesimus back “no longer as a slave, but more than a slave,” it seems certain that Paul is not saying that Onesimus will now serve Philemon permanently as a slave. To “have him back forever” should, therefore, refer to the new relationship that transcends earthly relationships, and this is likely what Paul means with the phrase “a beloved brother” (v. 16).

16a-c No longer as a slave, but more than a slave, a beloved brother (οὐκέτι ὡς δοῦλον ἀλλὰ ὑπὲρ δοῦλον, ἀδελφὸν ἀγαπητόν). Paul now explicitly articulates the new relationship between Philemon and Onesimus. Modifying the verb “you may have … back” (ἀπέχῃς), this verse provides further definition as to how Onesimus is to be received. This phrase modifies the purpose clause with its subjunctive verb ἀπέχῃς, so one might have expected μηκέτι rather than οὐκέτι for “no longer.”100 The use of οὐκέτι here may serve to emphasize that “ ‘no more than a slave’ is an absolute fact, whether Philemon chooses to recognize it or not.”101 If so, the significance of this statement in Paul’s rhetorical strategy should not be missed.

The particle “as” (ὡς) has been taken in a number of ways. Least likely is the reading that takes this in the counterfactual sense of “as though.” This reading assumes that Onesimus is not literally a slave and should not be treated as one.102 This use of the particle is absent from the NT (except perhaps in 2 Cor 10:9). It is best, therefore, to consider this as a “marker introducing the perspective from which a per., thing, or activity is viewed or understood as to character, function, or role.”103

Even so, it is not clear whether this particle introduces merely a subjective perspective or one that reflects an objective reality (at least in the opinion of the author). For some, ὡς points merely to Paul’s subjective reading of the situation, without challenging the objective reality of Onesimus’s status as a slave.104 But it is questionable whether Paul would consider the reality in Christ, where there is neither “slave” nor “free” (Col 3:11) in the new humanity brought about his redemptive death, as merely a subjective reading. One cannot deny, however, that ὡς does point to a reality that may escape human eyes. “No longer as a slave,” therefore, points to a reception of this slave within a new framework that acknowledges the relativization of the present social and political reality without necessarily denying such a reality in the present age. This is consistent with Paul’s exhortation to the slaves in Col 3:23: “whatever you do, do it wholeheartedly, as [ὡς] to the Lord and not to people.”

This understanding is perhaps confirmed by the next phrase, “but more than a slave” (ἀλλὰ ὑπὲρ δοῦλον). The preposition “more than” (ὑπέρ), by itself, does not necessarily deny the reality of a slave’s earthly status, but it does point to his new status as “surpassing” that of his present identity.105 When Paul further defines this phrase through the words “a beloved brother” (ἀδελφὸν ἀγαπητόν), readers are again reminded of the ambiguity and tension with the presence of these competing realities. While some see behind this juxtaposition of labels as pointing toward a call to manumission,106 others see Paul as less concerned with the social relationships at this point.107 Such ambiguity has also led some to conclude that Paul himself “did not know what to recommend.”108

Before surrendering to such interpretive despair, a few points need to be made. First, within the social reality of the first-century Roman world, a simple call to manumission without changes to the entire Roman social and political system would simply be considered as an idealistic move. Moreover, in such contexts, “manumission would have diminished Philemon’s obligations without increasing Onesimus’ well-being or security.”109

Second, regardless of whether Paul is calling for Philemon to manumit his slave, the progression of thought in this verse clearly points to the significance of a new set of relationships among these brothers in Christ.

Third, the adjective “beloved” (ἀγαπητόν) should also be noted. As Philemon is the “beloved” in v. 1 and as he has consistently expressed his “love for all the saints” (v. 5; cf. vv. 7, 9), he is urged to fulfill this trajectory of love in his reception of Onesimus. This love transcends the old realities that include both their former statuses as well as the possible tensions between them.

Finally, the striking juxtaposition of the titles “slave” and “brother” is noteworthy. Not only is it unique in the NT,110 but the fact that slaves are considered aliens within the household highlights the significance of this sibling language. Note too that manumission itself would not only fail to remedy this situation; it could further alienate the slave from the household, since to “free a slave meant not only to alienate family property, but also to disengage a member, though an inferior one, from the oikos.”111 Within the social and political reality of the first-century world, therefore, to consider a “slave” as a “beloved brother” is at least as significant as the mere call for manumission would be.

16d-f Especially to me, but how much more to you, both in the flesh and in the Lord (μάλιστα ἐμοί, πόσῳ δὲ μᾶλλον σοὶ καὶ ἐν σαρκὶ καὶ ἐν κυρίῳ). Building on his own relationship with Onesimus, Paul now urges for the transformation of the way Philemon relates to Onesimus since both Onesimus and Philemon are Paul’s sons in the faith. The combination of the superlative adverb “especially” (μάλιστα) with its comparative form “more” (μᾶλλον) has been labeled as an “enthusiastic illogicality”112 that can be rendered literally as “most of all to me … more than most of all to thee.”113 “Especially to me” draws attention to the close relationship between Paul and Onesimus, as Onesimus became Paul’s son during his imprisonment (v. 10). “How much more to you” then points to Philemon’s newfound relationship with Onesimus as a sibling within the household of God.

Moreover, in the context of Paul’s wider argument, this superlative-comparative combination takes on added rhetorical force. If Onesimus is most important to Paul, he is to be even more important to Philemon precisely because Onesimus is not simply his “beloved brother” in Christ; he is also Paul’s son. Underlying this emphatic note is the assumption that will be made explicit in v. 17: “receive him, as you would receive me.”

The contrast between “in the flesh” (ἐν σαρκί) and “in the Lord” (ἐν κυρίῳ) completes the thought of this sentence. This contrast can be found nowhere else in Paul’s writings, but the discussion of household relationships in a letter addressed to the same wider community may help. In Col 3:18–4:1, the lordship of Christ is repeatedly affirmed through the title “Lord” (3:18, 20, 22, 23, 24; 4:1). Significantly, it is in this context that the masters of slaves are identified as “the masters/lords of the flesh” (lit., τοῖς κατὰ σάρκα κυρίοις, 3:22). In that Colossian context, the authority of the “masters” is relativized through the reference to the “flesh.” In this context, however, the strategy is reversed, and the point is striking. One would have expected Paul to say that Onesimus is to be received as a slave “in the flesh,” but a “beloved brother in the Lord.” Instead, Paul applies both prepositional phrases to the “beloved brother.”114 That is to say, Onesimus is a “beloved brother” not simply in a spiritual sense, but also in an earthly sociopolitical sense.

Several implications can be drawn from this claim. First, as noted above, the climax of this sentence indeed lies in the claim that Onesimus is to be treated as “a beloved brother.” This application to this contrastive pair points to the comprehensive scope of this reality within the household of God. Although manumission may not be the main point of this passage, it is Onesimus’s status as a “beloved brother” that is the focus of Paul’s concern here. Moreover, if he was converted as a household slave when Philemon was converted, his true conversion under the mentorship of Paul would allow him to return to his household as a full member of the household of faith.115 At the end, Paul is as concerned with convincing Philemon of the significance of this new reality as he is with Philemon’s proper reception of Onesimus as a full member of this household.

Theology in Application

More than Freedom

Contemporary readers of Philemon often focus on Paul’s precise position concerning the manumission of Onesimus. Most, however, are disappointed with what they find in this text. Those who see manumission behind this text highlight v. 16 in particular: “no longer as a slave, but more than a slave, a beloved brother … both in the flesh and in the Lord.” The fact that the final prepositional phrases modify “a beloved brother” points to the earthly significance of Onesimus’s new status as a brother in the household of God.

Moreover, the development of Paul’s rhetoric that climaxes in his labeling Onesimus as “a beloved brother” also draws attention to this new label as one that at least relativizes his (former) status as a slave. Those who do not see this as a call for manumission point to the absence of any explicit call that can be interpreted as such. Furthermore, the fact that Paul writes “no longer as a slave” rather than “no longer a slave” points to his lack of interest in challenging this social institution. What both sides can agree on is the fact that Paul could have been clearer in making his intention known, at least as far as this issue of manumission is concerned. This has also led some to conclude that Paul himself is not exactly certain as to what he would like to recommend.116

Instead of focusing on the issue of manumission, readers should allow Paul to set the agenda for his own writing. In this case, he writes as an apostle and not as a philosopher whose task is to outline an ideal state or as a political operative who has the power to bring about systemic changes to the social and political reality of the first-century world. He is not, however, ignorant of such discourses or disinterested in such visions. In this letter, however, Paul is confronted with a more immediate problem with the status and identity of Onesimus. Instead of simply seeking to disengage Onesimus from the household of Philemon so that he can serve Paul in his imprisonment, he attempts to accomplish a far more difficult task, one that leads to a far more nuanced and sophisticated letter.

Identifying himself primarily as one who serves “Christ Jesus” (v. 1), Paul sees his primary task as convincing both Onesimus and Philemon to accept the reality that the gospel of Christ introduces. As one who considers himself the father of Onesimus (v. 10), Paul seeks to have him returned to his household and to become a full member of this spiritual household. Instead of spending effort in convincing Philemon that he can live without Onesimus, he does the reverse. Thus, one finds the emphasis on Onesimus being “useful” (v. 11) and his being “no longer as a slave, but more than a slave” (v. 16). Onesimus is to return to Philemon, and with a proper reception, they will be able to testify to the new humanity that is in Christ (cf. Col 3:11). Choosing a path that transcends manumission, on the one hand, and upholding the status quo, on the other, Paul considers both options as detrimental to both Philemon and Onesimus. Instead, he insists on having them relate to one another as “beloved brothers” (cf. v. 16), because they are both “beloved” in the eyes of God. Therefore, “both in the flesh and in the Lord” (v. 16), Paul expects them to live out the reality of the gospel message.

For contemporary Christians, we must also be reminded of the primacy of this gospel message and the reality it brings. Though unpopular in some circles, evangelism and missions still form the heart of our Christian calling. But this is not to ignore the present reality of struggles or to romanticize the systemic evil that can be identified around us. Instead, we are called to focus on the gospel message that demands so much more from us. It is a gospel that testifies to a God who is not simply a projection of our human imagination:

It is obvious that this God’s name of Father is not merely an echo of the experience of fatherhood, masculinity, strength, and power in this world…. No, this God is a different God … a God who does not overthrow the existing legal order and the whole social system, but who tempers it for humanity’s sake; and a God who consequently wants to have the barriers of categorization between good people and bad, friends and foes, neighbors and strangers, workers and unemployed, removed. How? By humility, self-denial, love, forgiveness without end, service regardless of reward, sacrifice without compensation.117

Through the death of his Son on the cross, this God is able to conquer the world through an utterly powerless act, but one that challenges all powers and authorities (Col. 1:15–20). In refusing to use his apostolic power to proclaim freedom for Onesimus, therefore, Paul is testifying to the gospel of this cross, a gospel that refuses to challenge the structure of this world simply through the powerful instruments of the world.

Rhetoric of Weakness

In shifting the focus away from the individual thirst for freedom, Paul focuses instead on the believers’ freedom to serve one another and to find their identity in Christ. In articulating this vision, Paul makes it clear that he himself is also willing to give up his freedom for the sake of the gospel. As a “prisoner” (vv. 1, 9) and an “old man” (v. 9), he submits to a reality in which the exercise of his own will is no longer his primary concern. The decision to “appeal … on the basis of love” (v. 9) is, therefore, not merely a rhetorical ploy; it reflects the refusal to exercise the rightful power he possesses, especially since Philemon owes him his “very self” (v. 19). This also explains his decision to send Onesimus back so that Philemon can exercise his right to make the right decision through his “voluntary” will (v. 14).

This rhetoric of weakness is no mere rhetoric. For Paul, this points to the reality of the cross, and this is to live out the gospel of this cross through which reconciliation is possible (cf. Col 1:21–23). In this letter, therefore, Paul highlights the framework within which one should love, without explicit commands that are to be followed. Paul refuses to succumb to the temptation to exercise his power so that Philemon can give up his own. If there is a “power” about which he can “boast,” it is the power in his weakness, as he states elsewhere:

I will boast all the more gladly about my weaknesses, so that Christ’s power may rest on me. That is why, for Christ’s sake, I delight in weaknesses, in insults, in hardships, in persecutions, in difficulties. For when I am weak, then I am strong. (2 Cor 12:9–10)

This rhetoric of weakness is possible because Christ “was crucified in weakness, yet he lives by God’s power” (2 Cor 13:4).

This demonstration of a life that submits to weaknesses in turn becomes a powerful argument for Philemon to give Onesimus his own life. As Paul is willing to give up his claim over Onesimus (v. 13), Philemon should do the same. As Paul resists exercising his will over others (v. 14), Philemon should do the same. As God is the sovereign one who stands behind the events that have transpired (v. 15), Philemon should also yield to God’s sovereignty. Following the affirmation of that sovereignty and the willful submission to God’s will, Paul launches the most powerful argument possible for Philemon to give up willfully his rights over Onesimus so that he too can serve God with his own will. Even without a call to manumission, one does find a powerful basis for such a call. This call seeks neither to “accommodate” nor to “colonize” the world, but it will bring new life into this present existence simply because one has been born into this new reality:118

Christians do not come into their social world from outside seeking either to accommodate to their new home (like second generation immigrants would), shape it in the image of the one they left behind (like colonizers would), or establish a little haven in the strange new world reminiscent of the old (as resident aliens would). They are not outsiders who either seek to become insiders or maintain strenuously the status of outsiders. Christians are the insiders who have diverted from their culture by being born again. They are by definition those who are not what they used to be, those who do not live like they used to live. Christian difference is therefore not an insertion of something new into the old from outside, but a bursting out of the new precisely within the proper space of the old.119

In Paul’s letter to Philemon, one finds a striking example of such a process wherein new believers are called to reevaluate their identity in their own social and cultural locations. This message is also relevant for contemporary readers who may not be struggling with issues of slavery. From self-centered and idolatrous lives that worship individual freedoms and rights, we must submit to the powerful demands of the gospel message and serve God with all our will and might. It is only in such a posture of weakness that we can experience God’s power, a power that bursts forth in our present existence.

What are some modern manifestations for such quests for individual freedoms and rights? Within our churches, these may include insisting on one’s own opinion in the name of divine inspiration, competing for power and attention, or trying to dominate in committees and worship teams. In our workplace, these may include an insatiable desire to get ahead by whatever means, or the urge to establish one’s status within the corporate system at the expense of Christian witness. In society at large, such quests for individual freedoms and rights lurk behind our positions in numerous social issues such as abortion, euthanasia, or sexual ethics. In all these, Paul’s rhetoric of weakness reminds us not to assume the posture of the autonomous self but to recognize our place within the created order and the wider plan of God.

For the Kingdom of God

By insisting on a rhetoric of weakness that looks beyond individual freedom, the focus on the kingdom of God should not be missed. Paul’s self-identification as a “prisoner of Christ Jesus” (vv. 1, 9) already points to a christocentric framework of reference. The reference to Onesimus being “useful to you and to me” (v. 11) likely refers to Onesimus’s new service as a believer, and Paul’s wish to keep him so that he might serve him on Philemon’s behalf during his “imprisonment for the gospel” (v. 13) points to the heart of Paul’s request. These statements are peripheral while the fate of Onesimus lies at the center of attention, but they are central to Paul’s agenda as he focuses on what will benefit the ministry of the gospel.

Far from being a theologically deprived letter, the letter to Philemon reveals a profound theocentric and christocentric vision. Paul’s indirect request to have Onesimus serve him as he is imprisoned “for the gospel” (v. 13) points to a missions-driven agenda, and the concern to have Philemon relate to Onesimus as “a beloved brother” (v. 16) situates this relationship within the wider ecclesiological discussions where the sibling language plays an important role in depicting the new community that submits to the lordship of Christ. These missiological and ecclesiological emphases are grounded in Christ’s redemptive death, which may have provided the model for Paul’s own offer in v. 18 (see comments). Elsewhere in Paul, it is explicitly noted that believers can relate to one another because of the death of Christ: “So, my brothers and sisters, you also died to the law through the body of Christ, that you might belong to another, to him who was raised from the dead, in order that we might bear fruit for God” (Rom 7:4).

Contemporary readers should take note of the significance of this theocentric and christocentric message, which will impact the lives of individuals navigating through the implications of their own claims as members of the household of God. In drawing attention to these dimensions that may not be the immediate concerns of Philemon, Paul reminds him of the priority of this new reality. Those among us who are also struggling with their own daily struggles will do well if they are also reminded to seek first the kingdom of God (see Matt 6:33).