Chapter 15

Philemon 21–25

Literary Context

As we noted in our discussion of the delineation of the main body of this letter, it is best to see v. 21 as beginning the concluding remarks of this letter.1 The previous subsection (vv. 17–20) builds on the relationship between Paul and Philemon as Paul listed his demands. This is highlighted by the repeated use of the first person pronoun (“I” in vv. 19, 20; “me”/“my” in all verses). Paul urged Philemon to act properly in light of their partnership and also offered to repay any debt owed to Philemon while reminding him of his own indebtedness to Paul (vv. 18–19). He concluded by asking Philemon to refresh his own heart (v. 20; cf. v. 7).

In this final section, Paul begins by expressing his confidence that Philemon will be obedient to his demands and requests (v. 21). This note of confidence signals the beginning of the closing section as it refers back to the entire main body of the letter.2 In v. 22, one finds another specific instruction as Paul requests Philemon to prepare a room for him for an upcoming visit. In light of the presence of this specific instruction, some consider the main body of the letter as extending to v. 22. (cf. GNB, CEV, NEB, HCSB, NET, NLT, ESV).3 It is clear, however, that the instruction in v. 22 is of a different nature than those provided in vv. 17–20. First, the instructions in vv. 17–20 are all focused on Onesimus, although Paul grounds such instructions on his relationship with Philemon. In v. 22, however, the instruction focuses squarely on Paul’s visit. Second, by the time of Paul’s future visit (v. 22), all the requests noted in vv. 17–20 should have been performed. This again points to the disjunction between the two sections. Finally, this note of Paul’s visit is consistent with distinct sections of his letters where he discusses his travel plans (cf. Rom 1:8–15; 15:14–33; 1 Cor 4:14–21; 2 Cor 12:14–13:13; Gal 4:12–20; Phil 2:19–24; 1 Thess 2:17–3:13).4

Main Idea

Paul reinforces his preceding arguments by expressing confidence in Philemon’s obedience as well as noting his own impending visit. This letter concludes with a list of greetings and a closing benediction, thus framing its content with references to the wider ecclesiological and theological contexts.

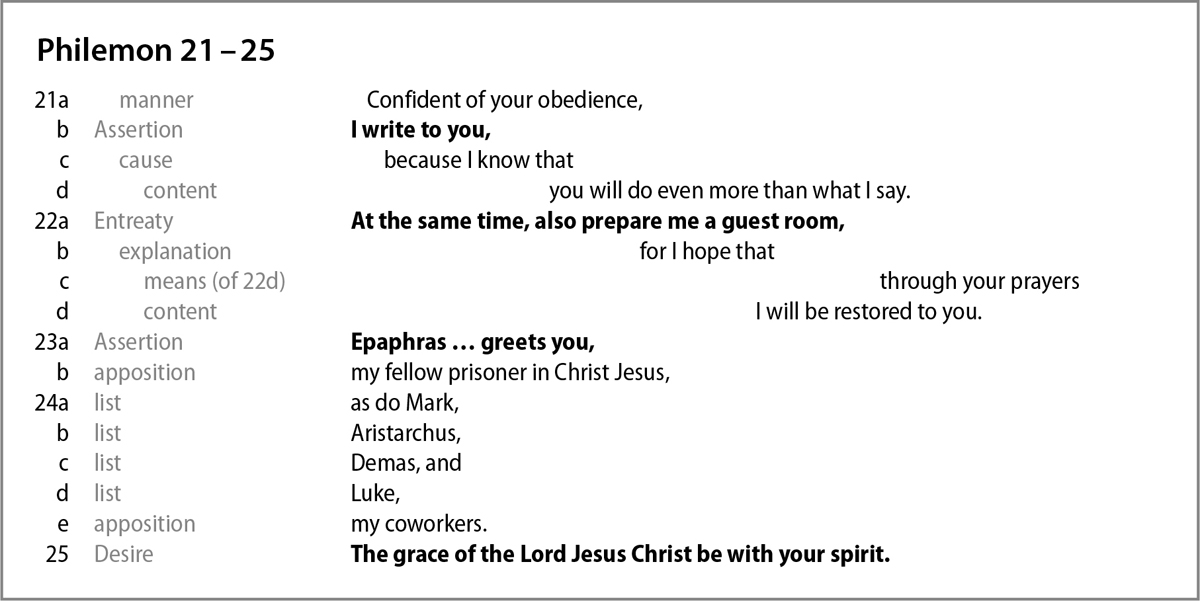

Translation

Structure

After the main body of this letter (vv. 8–20), Paul gives further instructions that underline the need for his requests to be followed (vv. 21–22). Shifting from his earlier emphasis on appealing to Philemon on the basis of love (v. 9) rather than command (v. 8), Paul now uses the language of “obedience” (v. 21a) in expressing his expectations for Philemon. He goes on to mention that he expects Philemon to do even more than what is specified in this letter (v. 21c-d). Despite the difficulties in discerning exactly what is implied in this statement, it is clear that Paul’s desire is not limited to what is explicit in the main body of the letter. This subtle hint aims at forcing Philemon to act beyond the requests made, so that he can be faithful to the faith he confesses as well as to the partnership he shares with Paul.

The instruction for Philemon to prepare a room for him in his next visit (v. 22) also acquires significant rhetorical force as Paul reminds Philemon that he will be held responsible for fulfilling the stated and implied requests of the letter. Obscured by contemporary English usage, the shift from the singular verb to the plural pronoun should be noted: “prepare [second person singular] me a guest room, for I hope that through your [plural] prayers I will be restored to you [plural]” (v. 22). This shift paves the way for the greetings that follow as the wider circle of believers becomes witnesses ensuring that Philemon will provide the proper response.

In the final greetings, Paul first conveys greetings from Epaphras, whom he identifies as his “fellow prisoner in Christ Jesus” (v. 23). Likely the founder of the church of Colossae (cf. Col 1:7; 4:12), Epaphras is singled out in this final greeting section, perhaps again to make it clear that this is not simply a personal and private letter. The others listed (Mark, Aristarchus, Demas, and Luke) are all identified as Paul’s “coworkers” (v. 24).5 As in his other letters, Paul closes with a final benediction (v. 25).

Exegetical Outline

- I. Final Greetings (vv. 21–25)

- A. Further instructions (vv. 21–22)

- 1. Expected Obedience from Philemon (v. 21)

- 2. Call to prepare for Paul’s visit (v. 22)

- B. Greetings from Paul’s coworkers (vv. 23–24)

- 1. From Paul’s fellow prisoner, Epaphras (v. 23)

- 2. From Paul’s coworkers (v. 24)

- a. Mark (v. 24a)

- b. Aristarchus (v. 24b)

- c. Demas (v. 24c)

- d. Luke (v. 24d)

- e. Summary (v. 24e)

- C. Benediction (v. 25)

- A. Further instructions (vv. 21–22)

Explanation of the Text

21a-b Confident of your obedience, I write to you (Πεποιθὼς τῇ ὑπακοῇ σου ἔγραψά σοι). Though refusing to evoke his apostolic authority, Paul expresses confidence that Philemon will be obedient to his requests. Some prefer to see this statement as the climax of the previous section “since there is no abrupt shift in subject matter.”6 This, however, ignores several shifts in both focus and tone. First, the use of a perfect participle (“confident,” πεποιθώς) at the beginning of this sentence is significant since it is the first nonfinite verb after vv. 17–20. Although the imperative reappears in v. 22, this section is no longer dominated by specific instructions for Philemon.

Second, in the previous section, Paul focuses on appeals based on love (v. 9); here he uses language of “obedience.” This shift in tone should not go unnoticed no matter how the concept of “obedience” is to be understood.

Finally, the reference to “more than what I say” also serves as a marker as Paul now moves beyond the previous discussion in pointing to what must yet be uttered.

The word translated “confident” (πεποιθώς) carries the nuance of “persuade, trust, obey.” In the perfect tense, it can refer to the act of being “so convinced that one puts confidence in someth[ing].”7 Most contemporary English translations rightly render this verb as “having confidence” (KJV, ASV, NASB, NKJV) or simply “confident” (NRSV, REB, TNIV, ESV, NIV).8

The reference to Philemon’s expected “obedience” (τῇ ὑπακοῇ) is a bit surprising, especially in light of Paul’s earlier decision not to evoke his (apostolic) authority (see vv. 8–9). In Paul, this term often refers to the believer’s obedience to God (Rom 6:16; 15:18; 16:19)9 or to Christ (2 Cor 10:5), and by logical extension also to the gospel message (Rom 1:5; 16:26). Some suggest that “obedience” should be understood here in a weaker sense of “compliance”10 or “acquiescence.”11 That meaning is, however, unattested in Paul’s writings. Others, therefore, consider the implied object of obedience here as “Christ’s command,”12 “the will of God,”13 or “the gospel.”14

While the ultimate object of the believers’ obedience is certainly God and his Son, the role of Paul here cannot be ignored. His reference to Philemon’s obedient response to his own requests is implied in the second half of this verse: “because I know that you will do even more than what I say.” This is consistent with his repeated focus on his own role in his appeal to Philemon (cf. vv. 17–20). Elsewhere Paul also uses similar language as he considers himself as an intermediary agent of God; thus, he rightfully deserves such “obedience” (ὑπακοήν in 2 Cor 7:15; cf. Phil 2:12).15 Beyond the canonical corpus, one can also point to examples where such language within the “confidence-formula” can be used even among equals.16 Moreover, in vv. 8–9, Paul’s mere claim not to impose his authority on Philemon is itself a power claim, and Philemon’s obedience is expected. Therefore, Paul’s return to such language of authority is not unexpected as he provides a climactic note in his appeals to Philemon.17

“I write” (ἔγραψα) should again be taken as an “epistolary aorist.” Because of the same verb form in v. 19, however, some argue that it does not refer to the literal act of writing and should thus be rendered as “I send this letter to you.”18 In any case, it points to the authority embedded in this letter penned and sent by Paul.

21c-d Because I know that you will do even more than what I say (εἰδὼς ὅτι καὶ ὑπὲρ ἃ λέγω ποιήσεις). With this clause that also begins with another perfect causal circumstantial participle, Paul makes another ambiguous request of which the meaning is left unspecified. Much speculation surrounds the reference behind “more than what I say.” Many are confident that this “more” refers to “Philemon’s bringing the legal aspect of his worldly relationship with Onesimus into conformity with the social structural ground of their new churchly relationship, presumably by legally freeing Onesimus.”19 Others consider this ambiguity as a way for Paul to allow Philemon to respond in his own way to the wider theological framework laid out in this letter.20 An extreme version of this reading is the conclusion that Paul himself is unsure as to the best course of action to recommend.21

To suggest that Paul does not have a solution in mind fails to take into account the carefully crafted main body of this letter, where Paul does provide a detailed theological vision within which Philemon is to act. Manumission does not seem to be the embedded meaning behind this clause, however, since in v. 16 he has already moved beyond the limited concern of the legal status of Onesimus. If a solution can be found in this letter, it is located in v. 13, where Paul explicitly desires to keep Onesimus so that he can be of service to him and the gospel he preaches. If so, this “more” should be considered as a veiled request for Philemon to allow (or free) Onesimus so that he can return to Paul for the further service of the gospel mission.22 Manumission is not quite enough for Paul since Onesimus is not simply to be disengaged from his household; he is also to be engaged in the household of God to play a role in God’s mission on which a new humanity is being built (cf. Col 3:11).

22a At the same time, also prepare me a guest room (ἅμα δὲ καὶ ἑτοίμαζέ μοι ξενίαν). Paul concludes his appeal to Philemon with a note of his impending visit. The particle translated “at the same time” (ἅμα) is a “marker of simultaneous occurrence.”23 The translation of this phrase as “and one thing more” (TNIV, NIV; cf. NRSV) is acceptable if it is not understood merely as a casual thought that happens to come into Paul’s mind.24 Our translation sufficiently highlights the connection between this request and the previous one as Paul concludes this letter.

In Hellenistic Greek, the word “guest room” (ξενία) is most often used in the sense of “hospitality,”25 but both of its occurrences in the NT refer to a place where hospitable acts are performed (cf. Acts 28:23). The two usages are not entirely divorced from one another, however, especially in this context where Paul is likely not simply referring to an empty space for temporary lodging, but “a hospitable reception with all the amenities that good hospitality entails.”26 As his “partner” in faith (v. 17; cf. v. 6), Paul will also feel the need to receive such hospitality when he visits Philemon after his release from prison.

The significance of Paul’s request for Philemon to have a guest room prepared for him has been variably understood. On one end of the spectrum, this request is read as a “thinly veiled” statement comparable to Paul’s earlier statement in 1 Cor 4:21: “What do you prefer? Shall I come to you with a rod of discipline, or shall I come in love and with a gentle spirit?”27 Others see it as a promise as Paul looks forward to being restored to his partner.28 Based on both the rhetorical force of Paul’s preceding argument and his commitment to appeal to Philemon “on the basis of love” (v. 9), it seems best to consider Paul as intending to exert gentle pressure here as he expects Philemon to act appropriately in light of the theological framework outlined above.29

22b-d For I hope that through your prayers I will be restored to you (ἐλπίζω γὰρ ὅτι διὰ τῶν προσευχῶν ὑμῶν χαρισθήσομαι ὑμῖν). Paul here expresses a wish to visit Philemon through God’s gracious answer of the prayers of believers. While some argue that “I hope” (ἐλπίζω) completes the triad with “love” (v. 5) and “faith” (v. 5), this verb when used to describe Paul’s travel plans (cf. Rom 15:24; 1 Cor 16:7; Phil 2:19, 23) necessarily hints at a “tentativeness” that is absent in Paul’s other uses of this verb in reference to the hope that one finds in Christ.30 Here, Paul’s reference to “prayers” defers to God as the one who will ultimately determine the future plans and fate of Paul.

With this clause, one finds the return of the second person plural pronoun “your” (ὑμῶν) and “to you” (ὑμῖν). On the most fundamental level, this plural pronoun points to Paul’s belief that the entire community of believers in Philemon’s house church is praying for him (cf. Rom 15:30).31 In its immediate context, it also evokes the other members and leaders of this house church to hold Philemon accountable to the demands presented to him. This plural also paves the way for Paul’s final greetings to the believers there.

One can also identify “a strong recapitulating function” here as Paul points back to the beginning of this letter where other members of Philemon’s house church are noted (vv. 1–3).32 Thus, Paul again makes it clear that this is not a private letter. Not only will the other church leaders serve as witnesses to Paul’s demand and Philemon’s response, but they and their entire community will also be affected by Philemon’s decision.

“I will be restored” (χαρισθήσομαι) often carries the sense of “gracious provision” (cf. Rom 8:32; 1 Cor 2:12; Gal 3:18; Phil 1:29; 2:9),33 and its passive voice is best taken as a divine passive especially in a context where “prayers” are mentioned. Some translations, therefore, render this verb, “I will be given (back) to you” (NASB, NET), or even “I will be graciously given to you” (ESV), although such renditions may be awkward to our ears. In any case, Paul’s focus is not on restoration but on God’s gracious act of leading Paul to Philemon.

Many have considered this note on Paul’s desire to visit Philemon in Colossae as a strong evidence for this letter being written in Ephesus rather than in Rome, especially because Paul himself had expressed his desire to travel to Spain after his Roman imprisonment (cf. Rom 15:24, 28).34 This verse does not, however, necessitate this conclusion. First, the rhetorical intent of this note must be emphasized. While one cannot doubt Paul’s sincerity as he hopes to visit Philemon, this note reminds Philemon of the need to take the letter seriously. Moreover, a travel note such as this one serves more to express his desire to be with the recipient rather than outlining an itinerary. Finally, in light of the strong tradition in both the canonical text and in early Christian tradition that Paul did return to Asia after his Roman imprisonment, the actual distance between his place of imprisonment and Philemon’s location should no longer be considered a critical factor in this discussion.

23 Epaphras, my fellow prisoner in Christ Jesus, greets you (Ἀσπάζεταί σε Ἐπαφρᾶς ὁ συναιχμάλωτός μου ἐν Χριστῷ Ἰησοῦ). As in his other letters (e.g., Rom 16:3–16, 21–23; 1 Cor 16:19–20; Col 4:10–15; 1 Thess 5:26), this letter ends with words of greeting. The closest parallel to this section is Col 4:10–15, where Epaphras, Mark, Aristarchus, Demas, and Luke are also mentioned. In light of such similarities, the differences between this final section and the concluding section of Colossians (4:7–18) should also be noted. First, Paul’s signature in Col 4:18 is missing in Philemon, though see his handwritten note in Phlm 19, which may function in a similar way to Col 4:18; as we noted on v. 19, it is also possible that this shorter and more personal letter was entirely written by Paul.

Second, Tychicus, the letter carrier, is mentioned in Col 4:7–8, while Philemon has no such reference. This omission can probably be explained by the fact that the introduction of Tychicus in Colossians is meant to highlight his function as one who will explain Paul’s own circumstances. If we assume that Philemon is among the Colossian believers who have already received such information, to reintroduce Tychicus is unnecessary. Moreover, since this letter is likely to be carried by Onesimus himself, there is no need for yet another letter carrier.35

Third, in Colossians, the list of names is divided between Jews and Gentiles, while no such division is obvious here. This can be explained by the emphasis on the unity of God’s people in Colossians (cf. Col 3:11), whereas an ethnic concern is not the focus of Philemon.

Finally, the omission of “Jesus, who is called Justus” (Col 4:11) here should also be noted. Some have suggested that the final word of this verse should have a final sigma, thus referring not to Christ, but to this “Jesus”: “Epaphras, my fellow prisoner in Christ, greets you, so does Jesus” (ἀσπάζεταί σε Ἐπαφρᾶς ὁ συναιχμάλωτός μου ἐν Χριστῷ, Ἰησοῦς).36 Attractive as this emendation may be, it has no manuscript support. Therefore, it seems best to adopt the traditional reading even though it remains unclear why this “Jesus” is omitted from this list of greetings.

“Epaphras” is mentioned first, probably because of his prominent status among the Colossian believers. Since he was the one who spread the gospel to the Colossae area (cf. Col 1:7; 4:12), his name would no doubt further exert pressure on Philemon.

The term “fellow prisoner” (ὁ συναιχμάλωτός) can be understood in either a literal or a metaphorical sense. Those who argue for a literal reading37 must explain why the title is applied to Aristarchus rather than Epaphras in Colossians (Col 4:10; cf. Rom 16:7).38 In this case, however, the presence of the phrase “in Christ Jesus” suggests that this title should be taken metaphorically, both here and in Col 4:10.39 Moreover, since this term literally means “fellow prisoner of war,”40 Paul himself would not literally fit this category. The use of a different word group for his own imprisonment in v. 1 (“prisoner,” δέσμιος) also argues against taking this literally.41 It seems best, then, to take Paul as again evoking this imagery to urge Philemon to imitate those who are willing to give up their rights for the sake of the gospel.

24 As do Mark, Aristarchus, Demas, and Luke, my coworkers (Μᾶρκος, Ἀρίσταρχος, Δημᾶς, Λουκᾶς, οἱ συνεργοί μου). “Greets you,” which starts the Greek sentence in the previous verse, applies to each one of these names. Most English translations insert either “and so do” or “as do” to clarify the relationship between these two verses.

All four names appear in the final greetings in Colossians (Col 4:10, 14). “Mark,” the one identified as “the cousin of Barnabas” in Col 4:10, is likely the John Mark who joined Paul and Barnabas in their first missionary journey, but did not complete the journey and abandoned them in Pampylia (Acts 15:38), an act that caused the rift between Paul and Barnabas (15:39). His appearance in Colossians and here points to the reconciliation between Paul and Mark, and most probably also Paul and Barnabas. In a letter that emphasizes acts of reconciliation, the appearance of this name provides added significance.

“Aristarchus” is among Paul’s travel companions in Acts (19:29; 20:4). Originally from Macedonia (cf. 27:2), he was with Paul during the riot in Ephesus (19:21–41). In Colossians, he is identified as Paul’s “fellow prisoner” (Col 4:10), probably reflecting on their commitment to Christ and his gospel.

Unlike Mark and Aristarchus (identified as “Jews” in Col 4:11), “Demas” and “Luke” are likely Gentiles. Demas (see Col 4:14) is later described as one who deserted Paul (2 Tim 4:10–11). “Luke,” however, was a longtime companion of Paul, if we assume that he is the author of Luke-Acts and the character identified in the “we-passages” in Acts (16:10–17; 20:5–15; 21:1–18; 27:1–28:16). In Col 4:14, he is also identified as “the beloved physician.” By grouping Jews with Gentiles, longtime partners with more recent partners, and those who have at times failed with those who have always been faithful, Paul further emphasizes the breakdown of social and hierarchical boundaries in the gospel ministry.

These four are labeled as Paul’s “coworkers” (οἱ συνεργοί). This term is used elsewhere to identify those who serve with Paul (cf. Rom 16:3, 9, 21; 2 Cor 8:23; Phil 2:25; 4:3; Col 4:11),42 but its presence in the final section of the letter should be read in light of the appearance of the same term in v. 1, where Paul identifies Philemon as his and Timothy’s “coworker.” Since the entire letter is enveloped by such references, Paul points to a “common action and accountability” within which Philemon is to play his own part.43 Once again the public nature of this personal letter carries a significant rhetorical function. Moreover, to identify Philemon with other notable coworkers of Paul is to make the assertion that Philemon’s appropriate acts of obedience will also qualify him to be among those who participate in the ministry of the gospel.44

25 The grace of the Lord Jesus Christ be with your spirit (Ἡ χάρις τοῦ κυρίου Ἰησοῦ Χριστοῦ μετὰ τοῦ πνεύματος ὑμῶν). As in Paul’s other letters, this grace benediction is likely meant to replace the “farewell wish” often found in secular letters.45 Various forms of this benediction can be found in Paul’s letters, and the one Paul uses here is identical to that of Phil 4:23. Although formulaic in nature, such a benediction is not without significance in its own literary context as Paul concludes his presentation. Here, “grace” (ἡ χάρις) again evokes the opening “grace” and “peace” benediction (v. 3) as Paul frames his discussion with the theology of grace and reconciliation. Without the revelation of the grace “of the Lord Jesus Christ,”46 the transformation depicted by Paul will remain an unachievable ideal. In light of the reality of such divine grace, however, this transformation becomes a necessity demanded by the gospel of the cross.

“With your spirit” (μετὰ τοῦ πνεύματος ὑμῶν; cf. also Gal 6:18) should be understood simply as “with you.”47 “Spirit” here, even with the definite article, points to the human spirit rather than the divine Spirit. The exact reason for the inclusion of this word in these closing benedictions remains unclear,48 but the combination between the singular “spirit” and the plural “your” is noteworthy. This combination provides an emphatic note on the distribution of the divine grace among every single believer.49 It is this divine provision that allows Paul to write what he did and Philemon to respond the way he should.

Theology in Application

Obedience and Accountability

In this closing section of Philemon, Paul draws attention to the need to provide a proper response to what he has just written. The use of the word “obedience” (v. 21) is particularly important. As noted above, this word is most often used for one’s obedience to God or Christ. Such uses may suggest that behind this use of the word Paul is also pointing to the need for Philemon to be obedient to Christ and God. Nevertheless, to use this term here further bolsters the power of what is written in this letter: Philemon’s obedience to Christ and God is to be measured in light of the way he is obedient to the specific instructions embedded in this letter. The written word, therefore, provides the specific and concrete expressions of God’s will.

Setting himself apart from the moral philosophers of his time, Paul’s teachings carry an authority that demands an obedient response. This authority is derived from “Christ Jesus,” because of whom Paul is “a prisoner” (v. 1). Even though Paul’s mode of discourse in this letter is an appeal “on the basis of love” (v. 9), the source and basis of this appeal is Christ Jesus himself, and it carries a substantial force that cannot be ignored. For contemporary believers who encounter Paul’s letters, we are called to submit to the gospel embedded in these pages.

In this letter, the vocabulary of obedience is particularly important because obedience language often appears in the discussions of the relationship between masters and slaves (cf. Eph 6:5; Col 3:22). Elsewhere, Paul has already used this metaphor in the contrast between slavery to sin and obedience to righteousness:

Don’t you know that when you offer yourselves to someone as obedient slaves, you are slaves of the one you obey—whether you are slaves to sin, which leads to death, or to obedience, which leads to righteousness? (Rom 6:16)

In this letter where the issue of slavery is at the forefront, the use of such language is particularly striking. In calling Philemon to be obedient to the gospel that Paul himself preaches, he reminds Philemon that he is no different from Onesimus, for they are both slaves to a higher authority. Moreover, they are no different from Paul (v. 1), who is also a slave of Christ. This relativizes Philemon’s own relationship with Onesimus and puts this earthly relationship in its right perspective. Such use of the obedience language is, therefore, comparable to Paul’s own exhortation to the earthly masters: “Masters, provide for your slaves justice and equity, since you know that you also have a Master in heaven” (Col 4:1).

Paul makes it clear that this obedience is not simply an individual and personal response; it should characterize an entire community of believers. Here, the interconnectedness of believers is highlighted. First, in his request for Philemon to prepare a guest room for him for his next visit (v. 22), Paul reminds Philemon of his own presence as he expects to witness Philemon’s obedience to his earlier appeals. Second, the greetings from his “coworkers” (v. 24) also point to the public nature of this letter as Paul fully realizes that this personal matter is one that will involve the entire community of believers. In this closing section, therefore, Paul calls for the creation of a moral community defined by its obedience to God, Christ, and his gospel.50 It is within this community that this gospel message can become a living reality.

In an age when the gospel is often understood in therapeutic terms, the concept of “obedience” must be reintroduced in our churches. As individuals, we must be obedient to God’s will as expressed in the written Word. As God’s people, we must develop into communities accountable to one another as we seek to grow the body of Christ. Christian leaders should not shy away from disciplining or rebuking their flocks all the while allowing themselves to be open to warnings and corrections. Are we willing to build and participate in accountability groups so that we can be reminded of the need to be faithful to God? Are we willing to grow so that our local communities of believers can be mature in Christ?

Primacy of the Gospel Ministry

Paul reminds his audience here again of the primacy of Christ and his gospel. Returning to the issue of freedom and slavery, he reminds them that he himself is in chains, and he asks for prayers so that he can be released from his imprisonment (v. 22). His plans after his release are, however, no different from the reason why he was imprisoned in the first place, since his release from prison will not affect his status as “a prisoner of Christ Jesus” (v. 1). Taking the appellation attached to Epaphras, “my fellow prisoner in Christ Jesus” (v. 23), in the metaphorical sense, Paul emphasizes that it is not freedom but obedience that is the ultimate goal of the gospel message.

The passing reference to “prayers” (v. 22) points to Paul’s dependence on and submission to the divine will, and the formulaic note on “the grace of the Lord Jesus Christ” (v. 25) that concludes this letter is formulaic because of Paul’s conscious choice of words for the endings of all of his letters. Without such “grace,” Paul would have no gospel to preach, and Philemon would not be expected to be able to act the way Paul expects him to. All of these are possible because “it is by grace you have been saved, through faith—and this is not from yourselves, it is the gift of God” (Eph 2:8). This “grace” allows one to participate in God’s cosmic act of reconciliation through his Son (Col 1:6; cf. 1:15–23), and it is also this “grace” that allows two individuals to relate to one another in strikingly different terms (cf. vv. 15–16). Readers of these two letters, and of this commentary, can do no better than to rely on this divine grace as we seek to live lives consistent with the message we have received.