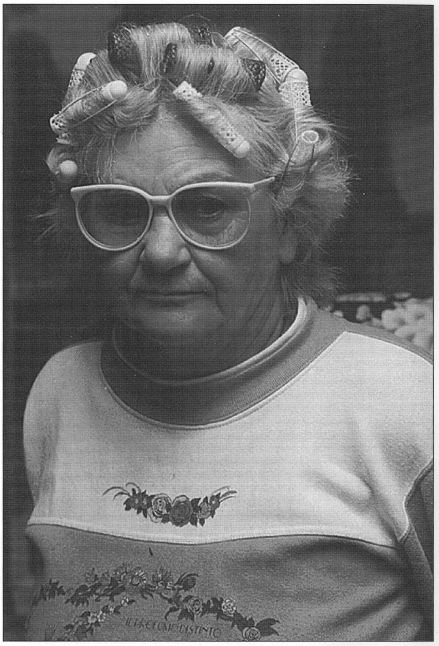

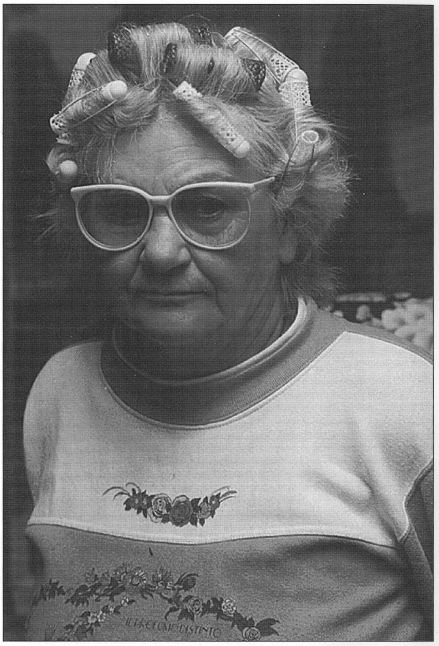

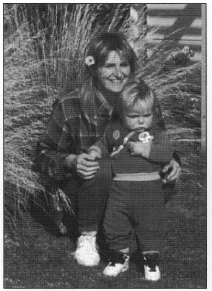

A bad hair day … grandmother and drug dealer Kath Pettingill on the day of her arrest.

TO Jim Wiggins, being a policeman meant more than locking up crooks. He believed he should be a leader in the community, a role model, someone to be relied upon.

Wiggins didn’t want to be another anonymous cop who worried about the job in office hours. To him policing wasn’t a job, it was his life. And, eventually, his death.

That was half a lifetime ahead on 2 April, 1972, when the young Jim Wiggins was one of 25 recruits who walked into the newly-acquired police academy, the former Corpus Christi College in Glen Waverley, to begin training. The recruits were grouped in alphabetical order. Wiggins roomed with a friendly young man named Ray Watson.

Watson, later a detective senior sergeant in the Armed Robbery Squad, was to remember his room-mate as a ‘keen and decent man.’

‘I joined the job with the hope of being a detective, but Jim was different. He wanted to serve the community in uniform in the traditional manner. He was pleasant, conscientious and friendly.’

He said he was not surprised when Wiggins took the job at the one-office station at Tarnagulla, an old goldfields town in central Victoria. ‘It seemed to suit him, he was a down to earth person.’ For Wiggins, it was a little like going home. He had been raised in St Arnaud, nearby, before moving to Melbourne when he was 16. He tried several jobs before deciding he wanted to be a policeman, but was on the borderline of the height requirements and had to undergo a series of stretching exercises before he made the limit.

Ray Watson last saw his old room-mate at the 20-year squad reunion. ‘He hadn’t changed. He was enjoying life and was the same talkative bloke I remembered. He seemed to be thriving.’

Jim Wiggins was no high flyer, but he seemed rock solid and unflappable. He had a steady, if unspectacular, career in eastern suburban police stations. His first marriage broke up, and he remarried in 1982. In 1989 he applied for the vacancy at Tarnagulla, 165 kilometres north west of Melbourne.

Those who knew Jim said he went bush because he thought he could make a difference there. In the city, policing was a round of grief and conflict. It meant shift after shift of trying to put a bandage on a weeping sore. In the country, he thought, it would be better. You could anticipate problems; try to deal them before it was too late.

‘He felt that working at Ringwood was like being a repairman who was given a list of jobs as long as your arm at the start of a shift and just kept going until the end of the shift,’ his wife, Helen, was to say.

‘He wanted to be part of a community. We went to Tarnagulla because we saw it as a change of lifestyle, a chance to get out of the rat race.’

Tarnagulla, once a bustling gold mining centre, is a fly speck on the map, a town of 200 people in the dry farming districts near Maryborough. Jim and Helen and their two children, Kate and Tara, moved into the police residence there in February, 1990.

The station had not changed much since the grandfather of the Chief Commissioner, Neil Comrie, was the lone policeman there. The young Neil Comrie used to play in the station’s lock-up, built 127 years ago to house drunken gold prospectors and would-be bush rangers.

There are 101 one-person stations in Victoria. About one per cent of the force is scattered around the state in these isolated domains.

It seems an attractive lifestyle. You are largely your own boss, with a car, a house and a position of respect in a close-knit community. But there is a downside. You live in a fishbowl where all your actions are open to scrutiny. Have a drink too many in the local pub and you’re a drunk. Lock up a popular local and you’re a demon.

As times have got tougher and the public purse smaller, the productivity demands on all police have become greater. In some areas one-man stations are expected to breathalyse 20 drivers a day in areas where they are flat out finding 20 cars.

Jim Wiggins’ best friend and confidante was Senior Constable Con Geurts, who controlled the patch 15 kilometres away at Dunolly. They watched each other’s back and kept in daily contact. Their families also became close. ‘I’ve got two boys and he had two girls. His daughters were the ones that I never had and my sons were the ones he never had,’ Geurts was to recall.

Geurts gradually became concerned about his mate. ‘He went through a little hassle. He was overdoing it.’ He said locals tried to get Wiggins to develop interests outside policing. They even got him to ride in the engine to Wycheproof on the wheat train as a distraction. His state of mind improved, but he was still obsessed with work.

‘He always thought of the job first. He gave 110 percent. It got to him in the end. I think he thought he couldn’t keep up his own standards. He had a big area to police with a small population. He was forever trying to justify the existence of the station because he was frightened it might be closed.’

He started a one-man road blitz and persuaded the local police command to give him a radar gun. ‘He said he would get 30 bookings a month. He would sit there for hours on the side of the road. He loved that radar.’

Con, look after the radar, mate.

In Melbourne there are police psychologists who work around the clock on stress cases. There are social workers, welfare officers, doctors, chaplains, and mates to weave a safety net. But in the one-man stations, police claim they are often left to work it out for themselves. Each district has a welfare officer, but police are often reluctant to talk about their inner problems to a superior.

According to Geurts, in the last 12 months of his life, Jim Wiggins, 42, was confronted with more grief, trauma and tragedy than hard-nosed city detectives working in the high crime areas of Melbourne would be expected to bear – but he had to do it on his own.’ Death just seemed to follow him,’ he said.

In one case, a local youth killed his step-father, then dumped the body in the bush, doused it with fuel and set fire to it. Wiggins had to guard the remains through a hot day, then escort them to Melbourne. He also had to spend a day guarding a cemetery after a grave robbery.

He found the body of a man who had suffered an epileptic fit and drowned. Later he found the remains of a man who had died several days earlier in a house, and organised a pauper’s funeral for him. He also found a man who had committed suicide at the side of the road.

Wiggins talked a suicidal young man into giving up his loaded .22 rifle during a dangerous confrontation. After any incident with firearms, police are required to accept counselling. He drove to Melbourne for a session with a psychologist which, according to Helen, lasted three minutes.

While this was going on he still had the town’s problems to fix. Police in one-man stations must try to walk the line between being everyone’s mate and the law. Some residents grumbled when the district Traffic Operations Group nabbed a local drunk driver. ‘Some people thought Jim should have warned him,’ Geurts said.

Helen Wiggins said her husband loved his job and felt a deep-seated responsibility to the town. Even when on holidays he would keep running sheets and attend to jobs. ‘It engrossed him. He became a policeman to the exclusion of everything else.’

The death message is every police officer’s most dreaded assignment. In the one-man stations it’s worse, because the policeman knows the victim and the family. It is nearly always much more personal. ‘You can’t walk away,’ his wife said. ‘Jim was a pall bearer at the funeral of people who had died in accidents he had attended.’

I served the people of Tarnagulla area to the best of my ability. I believe I’ve given all I can there’s no more.

Barry Condick has been a motor mechanic, Justice of the Peace, and Tarnagulla resident for 44 years. He remembers Jim Wiggins as a ‘special sort of man. He was the best country cop I have ever known and I’ve seen a few come and go. Everyone still wants to know why he did it. If he was unpopular it would be a different story, but he was well liked. If you had a problem he was always there.’

I’m not perfect, but I believe my life has been worthwhile – helping others.

‘He would sit out on the road with his radar for hours. Time meant nothing to him,’ Condick said. He seemed talkative and happy, and rarely spoke about police work. ‘He didn’t appear to worry about anything. Now I think he must have. He was never off duty. Maybe that was the problem.’

I’m so tired, I haven’t slept much over the past four days since Sunday. I simply feel depleted – anxious and upset with myself for being so neglectful and careless.

It wasn’t the big problems that sapped Jim Wiggins’s will to live. It was little things that shouldn’t have mattered. He charged two local brothers over not storing their firearms correctly, but felt a hypocrite because he had been doing the same thing for years. It evidently didn’t occur to him to use his discretion and warn them.

I’m no better, being a policeman I should know better.

Wiggins went to the faintly ridiculous length of removing the police sign from the front of his car so it wouldn’t forewarn speeding drivers. Then, racked with guilt, he drove to Bendigo headquarters to ‘confess’ to a senior officer over his actions. It was such a minor incident that it wasn’t taken seriously. No-one seemed to pick up the signs that the country copper was beginning to unravel.

On Thursday, 4 January, 1996, Jim Wiggins woke up alone and depressed. The small police residence was quiet. His wife and daughters were in Eildon on a holiday. They were due back the next day.

He rang Con Geurts, who drove over for a chat. ‘He was pretty low but after a couple of hours he ironed a shirt and said he was going to work.’ He gave no indication he was considering suicide. Geurts has relived that last conversation with his mate a thousand times. ‘I wasn’t to know he was so stressed. He hid it. He was coming around for tea that night. Sometimes I think, I hate the bastard for what he’s done, why did he hide it all from me? I could have helped.’

Sorry Con, I got worse as the day went on. Don’t in any way blame yourself.

Jim Wiggins headed off to Bendigo to try and get the transfer letters to replace the police sign on the front of the car. When he decided to commit suicide no-one will know, but he clearly wanted his wife out of town in the hope it would minimise the trauma. She was due home the next day. It may have been a case of ‘now or never’.

I couldn’t bear to think you would find me.

He had last spoken to his wife two days earlier and had given no indication he was dangerously depressed. ‘Jim was the last man on earth that I would have thought would take his own life. I am just lost for answers,’ she was to say.

She said he’d been talking about getting a gun safe and was seen on the Tuesday in uniform, without his gun in his holster. ‘Maybe it was a cry for help. Maybe he was trying to say, “Don’t let me near a gun”.’

She said she felt her husband may have become trapped in the role of the calm, rational policeman and could not talk of his depression. ‘Jim and I had to appear to be always in control. We were the people that others came to for help and comfort.’

When he returned from Bendigo it was business as usual. Several locals spoke to him and he appeared normal. No-one sensed the inner turmoil.

Jim Wiggins was quietly disintegrating, but in his last few hours he completed mundane police charges. He filled out paperwork and dealt with routine queries. He drove to see a local man and delivered a summons, as if he wanted to leave a clean slate.

Sorry to the people of Tarnagulla. You are the best To everyone I spoke with today I tried to keep up a happy appearance even though my gut was in a knot.

He returned to the station and at 2.40 pm began to tie up loose ends as he organised his own death. He tried to explain why a devoted family man, who was liked and respected and was doing a job he claimed to love, would end his life.

I have this feeling that I’ve let everybody down. The coward’s way out I couldn’t go without leaving a note. I believe it is wrong not to leave an explanation. Now that I’ve written this down I feel much better and relieved. There’s not much paper work to be completed.

He placed the keys to the police car on the table with a pencil and his sunglasses, next to his handwritten, four-page suicide note. Then, everything in order, Senior Constable Wiggins, still in full uniform, left the station and walked about 20 metres to the historic lock-up, unclipped his holster, withdrew his Smith & Wesson revolver, released the safety catch and, methodical to the end, shot himself dead.

The local community and the police hierarchy were shocked. The chief commissioner attended the funeral. But life goes on. Within weeks Helen Wiggins was told another policeman would be visiting the police residence the following day. He was considering applying for the Tarnagulla position.

It was no longer her family home. It was a house that went with a job – and the job was now vacant. She has since moved to Dunolly.

Helen Wiggins lost her husband and the father of her children. She also lost her identity. The police husband and wife are a team in small country town. The wife is as heavily involved in police work as the man in the uniform. She was the one who counselled victims, organised emergency accommodation, gave advice and helped where she could. But with her husband’s death she was now the victim. Her role in the community was gone.

She was not pressured to move, but when the day came, leaving the police house hurt her. ‘It was as though they were simply washing away Jim’s blood and installing a shiny new happy family to carry on as usual. I felt I was leaving him behind. I half expected him to drive down the road and park in the carport.’

She thinks police in one-man stations are misunderstood, that their value to the community cannot be measured by cold crime statistics or kilometres patrolled and could not be quantified on a balance sheet. ‘It is true community policing. They are everything from social workers to handymen. They are rung about anything and everything, from car accidents to fixing a globe on an outside light. It’s not unusual to find a policeman chopping the wood or mowing the lawns for a widow.’

Jim Wiggins said in his suicide note he wanted to be buried next to his father at St Arnaud. At the church service 500 people turned up, more than twice the population of Tarnagulla. The locals even ran a bus so that the aged and infirm could pay their respects.

Everyone said Jim Wiggins was a good bloke. But for him, it wasn’t enough.

WHEN police work alone they learn fast that the rule book doesn’t have all the answers. So says a man whose beat for 17 years was 3200 square kilometres of isolated mountain country.

Bernie McWhinney was a legend as the old bush copper from Jamieson, a knockabout with a blue singlet under his blue uniform. He could be seen propping up the bar in the local pub or patrolling the area on horseback. He still believes common sense was more important than rules and regulations.

‘I mightn’t have always done it according to the book, but there were no complaints. It was effective policing,’ he says of his remarkable career minding one of the biggest ‘patches’ in the state.

For 25 of his 28 years in the force McWhinney worked alone. In many ways he remained untouched by modern management theory. Commissioners came and went, district bosses were appointed and retired, but Bernie kept on being Bernie.

He would go to the pub and have a social drink in uniform, arguing he was always on duty, so what did it matter? When he was in the police residence next to the station he would always answer the door. Even when his marriage broke up in 1982, he still remained on duty and available.

A bad hair day … grandmother and drug dealer Kath Pettingill on the day of her arrest.

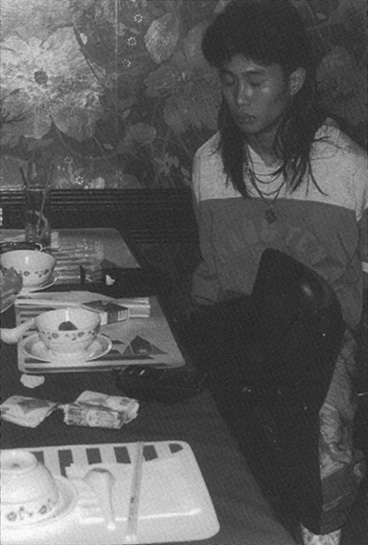

Drug dealer Viet Le took no notice of a birthday party at the next restaurant table. He should have. It was the NCA.

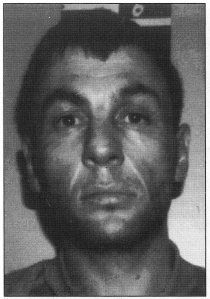

Melbourne and Sydney heroin trafficker Mengkok Te (left) caught by a police surveillance camera.

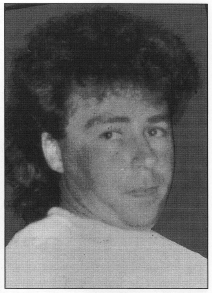

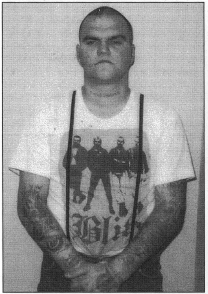

Dealer Steven MacKinnon with a woman now in police protection.

Wendy Peirce … says she’s finished with crime.

Peter Allen … ran a drug syndicate from inside prison.

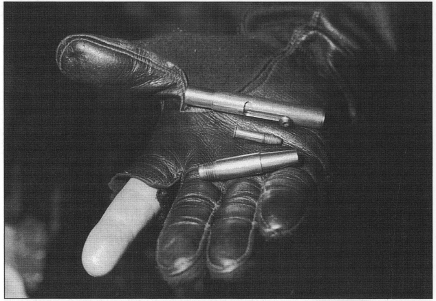

A pen pistol found in Kath Pettingill’s knickers.

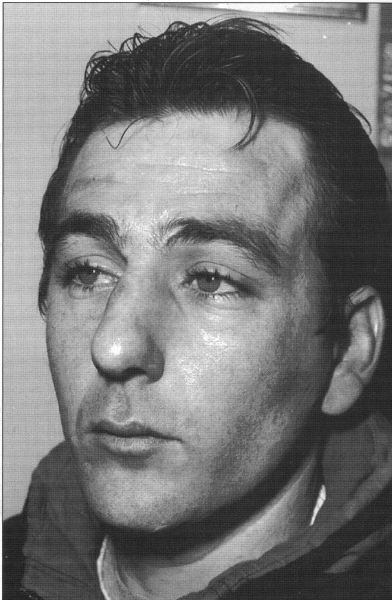

Trevor Pettingill … followed family tradition as a drug dealer.

Victor Peirce … allowed out of jail to go bowling.

Dennis Allen … his mum would search him for a police tape.

Dane Sweetman … neo-Nazi and fashion plate.

Greg ‘Bluey’ Brazel … clever, charming, cold-blooded killer.

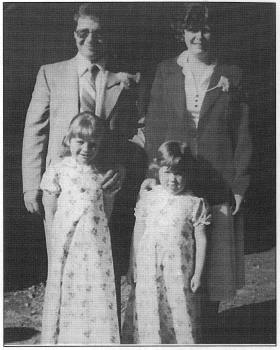

Missing … Edwina Boyle with husband Fred and daughters. She has not been seen since 1983.

Kerry Whelan … disappeared from a suburban carpark in 1997.

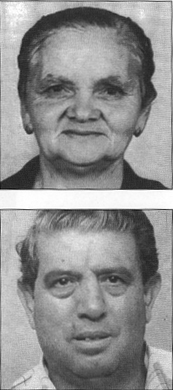

Multiple murderer Sandy MacRae.

Two of his victims, Rosa and Carmelo Marafiote.

Their son Domenic was buried by MacRae in this pit at his Mildura farm.

‘I was an old-fashioned kick ’em in the bum type of policeman. When the police force introduced computers I knew I was on the way out. I couldn’t even start one, still can’t. Today, if it isn’t on computer it didn’t happen,’ says the man who retired to drive trucks.

A ‘one manner’ soon learns he is more than just the local copper. He is the marriage guidance counsellor, family psychologist, tourist guide and the person everyone leans on.

According to McWhinney’s homespun wisdom, the first rule is always to have an answer. Even the wrong answer is better than none. ‘I don’t know,’ is not good enough.

‘There was an old bloke who was a little bit slow. He was in Melbourne when he was picked up by the locals for driving through a stop sign. He told them he couldn’t read at all and they cancelled his licence. He came to me and said; “It will ruin my life, Bernie”.

They would have crucified him. I knew that he mightn’t have been able to read but I knew he could drive. I got him the official written test, but he did my personal test over the kitchen table. I showed him pictures of the traffic signs and he could recognise them, even if he couldn’t read them. I was satisfied so I filled out his test paper.

‘Then I told him something which wasn’t strictly true. I said, “Bill, this is a special restricted licence. You can drive in Jamieson and Woods Point and to the edge of Mansfield, but nowhere else.” I even showed him where he could park at the edge of Mansfield.’

‘He was happy, but then someone told him that was wrong and he could drive anywhere. He was nearly cleaned up by a truck on the way to Benalla. I got him and said, “Bill, I’m the policeman and listen to me. You can’t go past Mansfield”. He was as happy as buggery.’

But while the idea of being The Law was attractive, the reality of being always on duty eventually can grind down those who work alone. ‘My door was always open. You would have someone come in and say he thought his kids were on drugs, and then someone who was worried his wife was playing up. You would counsel them, but who could you turn to? Welfare was three hours away in Melbourne.’

In 1987 McWhinney was severely bashed and spent a week in hospital. When the body healed he was left with emotional scars. ‘I needed counselling. I was pig headed at first and denied it, but in the end I knew I did. But it was a three hour trip, and when I finally got there it was the last thing I felt like. Sometimes you would scream out for someone to talk to, to spill your guts, someone to have a bawl to. I admit there were a few times I took a box of stubbies into the hills and drank most of them. There’s a couple of gay blokes up here who were probably the closest thing I had to counsellors. When I wanted a moan or talk about a problem I’d go to them.

‘But sometimes police need to talk to police. To sit in the mess room with six or eight other police. You can’t do that in a one-man station.’

He said even in the force, police didn’t understand the pressures of being the only law in town. ‘You might have to tell an old digger that his best mate has died in hospital. You spend an hour with him talking. You get in the car and over the radio someone will ask, ‘where the hell have you been?’ There was a lot of jealousy from the larger stations.’

But while McWhinney is full of tales of country people banding together, he still has the bitter after-taste.

‘I remember having to deliver the death message after someone had died in an accident. There were 12 people, six men and six women. They were laughing near the water, having the time of their lives. At first I couldn’t bring myself to tell them. Their day had been filled with laughter and I was going to turn it into a tragedy.’

That was more than 15 years ago. But Bernie McWhinney still remembers.