Neil Gordon Wilson … no one knows why he wanted to be a fish.

AT times she was a doting grandmother, clucking and fussing over her children’s children, but under pressure she showed the ruthlessness that made her a feared underworld figure for more than 30 years.

It took a heavy police taskforce, a tough female criminal and an undercover police officer posing as a yuppie snow skier to bring Kath Pettingill to justice, exposing her as an active drug dealer.

None of it might have happened without Rosina Power. She was a big, powerful woman with a tough streak and a keen sense of justice. When she heard that a man who lived near her was a suspected paedophile, she took matters into her own hands. Her husband was serving eight years for armed robbery, leaving her to bring up their three children alone. But he had hidden a double-barrelled shotgun inside a door in their house.

Rosina grabbed the gun, and she made a Molotov cocktail. She went to the man’s house, threw the fire bomb at it and blasted the front door with two shots. The next day the house was still standing so she bombed it again and fired more shots. She was arrested when she attacked the house on the third night.

She was sentenced to four years jail. While in Fairlea Women’s Prison she met Kath Pettingill, a grandmother, whose sons were considered among the worst criminals in Australia.

In 1993 Rosina Power was trying to make a new start. She moved into Wedge Crescent, Rowville, in Melbourne’s outer east. By a twist of fate one of her neighbours turned out to be Kath Pettingill. Like all good neighbours, Pettingill was soon on the doorstep to say hello. But instead of the traditional chat over coffee and cake, she came straight to the point. Would Ros like to move some drugs for her old prison buddy? Like a good host, Rosina walked into the kitchen to make her guest a cup of tea. But while she was there, she picked up the phone to ring a drug squad detective to tell him of the new neighbour from hell.

At 6.30 pm Pettingill returned to the house with her little grand daughter, but it was no Neighbourhood Watch meeting. She asked Power how much cannabis she could sell at $400 an ounce.

Kath said another of their close neighbours was also a dealer. On 15 May Rosina met Kath and the neighbour in a car outside the local milkbar and bought six small plastic bags of amphetamines for $300.

It was no big deal, but it sowed the seeds of Kath Pettingill’s destruction.

Rosina Power began to talk regularly to the Drug Squad detective. She agreed to introduce him to Pettingill as ‘Lenny Rogers’, supposedly a snow skier who wanted drugs to sell to yuppies on the slopes.

In May Pettingill went to Rosina Power’s home and gave her a plastic bag with an ounce of cannabis and several bags of speed. Power paid the grandmother $350 for the drugs the following day.

Kath Pettingill was a cunning old lag and she knew the way police worked better than some police did. She knew the best way to deal drugs was through a tight network, and never to strangers. But when Rosina introduced the man who called himself Lenny Rogers, she decided to take a risk. After all, Rosina was an old jail friend and Lenny seemed harmless. He didn’t look or act like a policeman or a crim. He didn’t talk tough and he appeared to be from another, more civilised world. In other words, to the street-smart Kath, he was a soft touch. A harmless mug.

But Kath knew the underworld was full of traitors and one night she turned on Lenny and demanded to search him, looking for a tape or gun. She always searched people, she explained. Even her own son, Dennis Bruce Allen. The feared underworld figure, known as ‘Mr Death’, was one of Australia’s biggest drug dealers and was involved in several murders before he died of heart disease.

Pettingill’s instincts were right. The conversation was recorded. It was a tense moment.

KATH: ‘Nobody’s guaranteed.’

LENNY: ‘I know.’

KATH: ‘Dennis never trusted me one hundred percent and I never trusted him one hundred percent, and he’s my son.’

LENNY: ‘Yeah, I know.’

According to police, Kath made further enquiries about Lenny, going as far as contacting corrupt former NSW detective, Roger Rogerson, to run a check on him. It came back clean.

Once Lenny had Kath on side, it opened all sorts of criminal doors to the undercover operative. If he was dealing with Kath, many criminals reasoned, then he was obviously worth knowing.

With Lenny working on the inside, police set up a task force that branched into two major investigations. Operations Earthquake and Tremor resulted in police moving in on amphetamine, heroin and marijuana rings, arresting sixteen people who were convicted and sentenced to a total 42 years jail.

In a series of buys Lenny purchased amphetamines, marijuana and heroin from Kath, her son Trevor Pettingill and their associates.

Most purchases were for at least $4000, but this wasn’t enough for Kath. She used Salvation Army emergency petrol coupons to fill the car she drove to do her drug deals.

Although she was making plenty of easy money, old habits died hard. She remained an active shoplifter.

She told friends the story of stealing a toy dinosaur for one of her grandchildren. She had slipped it under her clothes, next to her armpit and as she paid for other items at the checkout, the stolen toy began to slip and she had to squeeze it to make sure it didn’t fall. The pressure made the soft toy let out a growl. She pretended she had a bad case of wind and was making the growling noise herself. It worked. No store detective was prepared to confront an elderly woman making noises like an extra in Jurassic Park. Another shoplifting trip resulted in a haul of cosmetics and lingerie later sold at a discount through a suburban massage parlour. The grandmother took to wearing a see-through crochet white top in what was a rather bold fashion statement. Police were determined to make an airtight case. The fact that two of Kath’s sons, Victor Peirce and Trevor Pettingill, had been acquitted of the notorious ‘Walsh Street’ murders of young policemen Damian Eyre and Stephen Tynan in 1988, added to the detectives’ determination. They knew that any defence would be that police had planted evidence as a payback for Walsh Street. The taskforce wanted tapes and photographs that could not be disputed.

Kath Pettingill was like no other criminal. She called everyone ‘Love’, as if she were a friendly tea-lady. But she was often armed and had intimate knowledge of at least a dozen underworld murders.

On 26 July Kath went to Power’s house, produced a pen pistol from her knickers and said ‘have a look at my toy.’

At another meeting with Power, she chatted about business.

KATH: ‘Come in, love.’

ROSINA: ‘Hi Kath, how are ya?

Rosina followed Kath into Victor’s room. The grandmother sat on her son’s bed, produced a small Wizz Fizz spoon from a confectionary packet, and carefully used it to measure white powder into about six aluminium foils.

KATH: ‘I’ll just shut this door ‘cause all the kids’ll hear … Is your bloke happy with it (drugs) love?’

ROSINA: ‘Not too bad. He reckons if it was a bit better he’d be able to jump on it (dilute) a bit more. But he wasn’t, you know; he’ll make a bit, but not much.’

KATH: ‘What, complainin’ about it?’

ROSINA: ‘Yeah.’

KATH: ‘Fuckin’ kiddin’.’

ROSINA: ‘No. no.’

KATH: ‘We’ll look after ya, love, don’t worry … I made $2800 last night, love.’

The drug dealing in the street was an open secret. One night Rosina had every window in her house smashed and the words ‘DRUG DEALING SLUT’ daubed on her door. She could hardly defend herself by saying she was working undercover for the police.

During the operation Rosina walked up to Kath’s house with $1000 she had been given by police to buy amphetamines

KATH: ‘Yeah; oh, how are ya love.’

ROSINA: ‘How are ya.’

KATH: ‘All right.’

Rosina handed over $1000 to Kath.

KATH: ‘Oh, it’s the best love.’

ROSINA: ‘Yeah.’

KATH: It’s the best. I only get the best, you know that.’

Rosina was later to be put into witness protection, where she became one of the program’s success stories.

SLOWLY the police operation moved up the drug chain. It was nearly blown in August when Lenny was supposed to buy heroin worth $12000 from a drug dealer, Steven MacKinnon, known as ‘Stacker’.

Lenny arrived for a meeting at the corner of Johnstone and Hoddle Streets, Collingwood in a white Holden Commodore.

Stacker arrived on foot. He was furious, saying he had seen a man in a lane photographing the scene. He said the photograper had to be a policeman and he smelled a rat. Lenny remained calm and kept talking even when Stacker said he wanted to use a bottle to open the undercover’s head.

The group moved on to Footscray to meet the Chinese connection to get the gear. This time the Asian dealer spotted a police photographer. Stacker was livid. He began to shake with rage and accused Lenny of being an undercover policeman.

The butt of Stacker’s gun stuck out from his jacket. He wanted the money and he wanted it now. This was a deadly dilemma, a time when the only thing that stands between an undercover and a bullet in the brain is the ability to talk under pressure. No back-up police can move in quickly enough to help when flashpoint arrives.

If Lenny backed down his credibility in the criminal world would be ruined. Lenny took the risk and stood his ground, refusing to hand the money over without the gear. Stacker threatened to put Lenny in the boot of his own car. The deal was blown and MacKinnon stormed off. As Lenny became more accepted he was able to deal directly with the Chinese connection, Viet Le. He bought a quarter ounce of rock heroin at a Housing Commission flat in Collingwood for $3500. Later that day he bought a pound of amphetamines for $8500 from Trevor Pettingill.

That afternoon Le made contact to say he had given half an ounce rather than a quarter and wanted the balance back. In the drug world the idea of asking for drugs back was laughable, but Lenny did go back and hand over the difference.

Le was so impressed he dropped his guard and embraced his new found honest friend. He said that Lenny no longer needed an introduction, he could deal directly with the Asians. They would go to restaurants in Victoria Street, Richmond to deal.

Senior police were getting nervous. Stacker was still a loose cannon, and the longer the job went the greater the chance of it running out of control.

Le said he could sell Lenny eight ounces of heroin for $65,000. It was time to move after more than 15 controlled drug deals.

On 15 September Lenny bought two ounces for $21,000 from Le, with a promise of the balance to be provided the next day.

That was the day picked as the day to make the arrests. The key was to grab the offenders without letting anyone from the gang being warned. A series of co-ordinated raids were planned. Each offender would have to be arrested and isolated.

MacKinnon was arrested by Special Operations Group police at a Food Plus store in Preston and taken to the drug squad for interview.

Lenny and Power met Le at the Van Mai restaurant at 1 pm. The undercover had $56,000 to buy the drugs. Le said he could not get six ounces of heroin until the evening but he could get one ounce immediately. Le made a call on his mobile and then left the restaurant. He was handed the drugs by his dealer, Mengkok Te. He returned and handed Lenny an ounce of rock heroin. Lenny handed over $10,500 for it.

So happy was Le with the deal that he gave Lenny a small amount of amphetamines as a bonus. He said he would provide the rest of the heroin later that day and a pound of amphetamines in a few days. No-one was taking much notice of a group of twelve raucous office workers celebrating a birthday at the next table. The multi-cultural nature of Australia meant that a group of Anglo-Saxons shovelling down cheap Vietnamese food did not raise an eyebrow, although the diners made enough noise to raise the roof. The drug dealer and Lenny had to strain to hear each other as the nearby group sang ‘Happy Birthday’ and the guest of honour blew out the candles on the cake to loud cheers.

Le told Lenny they would be able to do business together and they were special friends. As the smiling Lenny was about to leave he made a pre-arranged gesture and the birthday party broke up.

The office workers were actually undercover National Crime Authority officers planted for the bust. Two pretended to head to the toilet, and as they passed the complacent Le, they swooped. The supplier, Te, was walking towards the restaurant to get his cut. He actually passed Lenny on the street. Surveillance police moved in and grabbed Te, who was also wanted in Sydney as a major importer of heroin.

Meanwhile, Kath Pettingill’s house in Venus Bay was searched. She might have seemed a charming old scallywag but she didn’t get a reputation as a gangster for nothing. When police searched her they found her pen pistol in her knickers.

Lenny had played his role so well that even as the boom was being lowered one dealer was trying to undercut Trevor Pettingill’s marijuana price by $400 a pound. His name was Edward Fiorillo, and he agreed to sell Lenny five pounds of marijuana for $22,000.

They arranged to meet near a cafe in Lygon Street, Carlton.

Lenny and Fiorillo met in a laneway. Fiorillo had a purple sports bag with the marijuana sealed in one pound lots. Lenny had $22,000. Police moved in to arrest Fiorillo, but he saw them and ran down Rathdowne Street. He was eventually arrested in a dead-end lane.

Police checked the dealer’s St Albans house. They found marijuana matching the drugs offered to Lenny. They also found marijuana hidden in the school cases of Fiorillo’s de facto’s child.

The Special Operations Group arrested Trevor Pettingill that evening in his flat in Collingwood. He was fairly relaxed as he had only a small amount of cannabis in the flat. His mood changed when he finally learned that one of his best clients, Lenny, was an undercover policeman.

Trevor Pettingill was sentenced to five years for drug trafficking, and his mother Kath to nine months. Le got three years jail, Te seven years and MacKinnon two years.

WHEN Wendy Peirce’s brother-in-law offered to shoot her in the foot for ‘the good of the family’ she thought about it for a while before declining the offer on the grounds that she was pregnant.

The brother-in-law was a notorious drug dealer, police informer and killer, Dennis Bruce Allen. The motive was to get Wendy’s husband, Victor Peirce, bail on compassionate grounds while he was awaiting trial for drug trafficking.

‘If I wasn’t pregnant it would have been all right. Dennis would have known how to do it without doing too much damage. Dennis shot himself in the leg once, when he didn’t want to go to jail. He wouldn’t trust anyone else to do it,’ Wendy Peirce said later.

Welcome to the world of Melbourne’s most infamous crime family, the Allen-Pettingill clan. Theirs is a world of violence, greed and betrayal, in which family members would take up arms against outsiders but then turn on each other, virtually on a whim.

Many criminals isolate their families from their ‘work’. The family home is sacred and safe houses are rented for underworld activities. But the Allen-Pettingill gang was different.

For them it was all mixed together. Children were brought up in households where people were killed, armed robberies plotted, drug deals struck, and guns as commonplace as stuffed toys. The kids grew up knowing Santa came down the chimney once a year, but armed detectives crashed through the front door a little more often.

Wendy had a massive falling out with Kath Pettingill when the older woman published her memoirs, The Matriarch, in 1996. It is purported to be the true story of Melbourne’s underworld during the past 20 years.

Few knew the workings of the underworld like Kath. She has worked as a brothel madam and a drug dealer. Six of her sons have been involved in virtually every serious crime on the statutes and some which should be. Two of the sons are now dead. Three of the remaining four were serving long jail terms by the mid 1990s.

But Wendy Peirce says her mother-in-law is an exploitative old woman, recycling family stories she has picked up over the years.

‘She’s a great grandmother now. She should be sitting down and doing the knitting not dragging up what has happened to us,’ she says. ‘She has brought my children into her book. She gave me a copy and wrote, “Wendy, if I have embarrassed you in this book I apologise, love Kathy.” When she rings I just hang up on her now. She’s written about things that have happened to me when she wasn’t even there. I’m disgusted.’

The Allen-Pettingill brood will always be associated with one of the worst crimes in Australia’s history. On 12 October, 1988, two young police, Damian Eyre and Stephen Tynan, were ambushed and murdered in Walsh Street, South Yarra. It was alleged to be a payback for police killing an armed robber, Graeme Jensen, during an attempted arrest in Narre Warren the previous day.

Two of Kath’s sons, Victor Peirce and Trevor Pettingill, and two family friends, Peter McEvoy and Anthony Farrell, were charged and acquitted over the Walsh Street killings.

Both Peirces had reasons to grieve over Jensen’s death. He was Victor’s best friend – and his wife Wendy’s secret lover.

One of the police task force’s main strategies in trying to gather evidence against the Walsh Street suspects was to get inside the close-knit Richmond tribe. First Jason Ryan, a nephew, turned to the prosecution, then Jason’s mother and Kath’s daughter, Vicki Brooks, agreed to give evidence for the police.

Police thought another key witnesses would be Wendy Peirce, who had made statements to detectives that her husband had admitted to her that he was one of the Walsh Street killers.

But for reasons Wendy finds difficult to explain, she changed her mind. When it came to the Supreme Court trial her story had changed. The police case was largely blown to pieces.

Police confidently predicted that Wendy had made the biggest mistake of her life and would ultimately pay for it with her life. But eight years after the murders and five years after the trial, she was still healthy and still married to Victor, the man she originally declared was a cop killer.

‘I was never going to give evidence against Victor. I don’t want to go into that all now. I think I had a mental breakdown, I was on heavy medications and I can’t recall all of what happened. I really don’t know why I did what I did,’ she said.

‘I love Victor and I know he loves me,’ she said. ‘He is a gentleman and a devoted family man. We had another child after that (Walsh Street) so it shows we are still together.’ The couple have four children ranging from voting age to kindergarten.

In 1992 Wendy was sentenced to 18 months with a minimum of nine for perjury over her evidence regarding Walsh Street. Her youngest child, Vincent, was five months old and went to jail with her.

Vincent was named after the Walsh Street trial judge, Justice Frank Vincent. Victor Peirce was sentenced to eight years with a minimum of six for drug trafficking. He had been in jail since his son was born. He was moved from the maximum security Barwon Jail to medium security at Bendigo and his earliest parole date was May, 1998. He was allowed to go ten pin bowling, cycling and long distance running outside of the jail while in custody.

Wendy maintains that Victor really had no choice but to go into crime in a big way. The Peirces lived in Chestnut Street, Richmond, next door to Victor’s brother Dennis Allen, who was making up to $70,000 a week through drug dealing. Allen once shot a bikie, Anton Kenny, and then severed his legs with a chainsaw in his Chestnut Street garage. It was not the ideal family environment.

Wendy met Victor when she was a business college student in 1977 and moved in with him shortly after. ‘I didn’t understand what sort of life we would lead,’ she said later. ‘I have come across murders. I’ve seen people shot, with their throats cut and bashed. It was a nightmare. I had to bring kids up during this. I was 17 when I got into this. I should be in a mental home.’

Peirce said she lived in a climate where any day a family tiff could be fatal. She recalled the day that Dennis Allen fought with his wife, Sissy Hill.

‘Dennis opened the boot. Sissy was in there with her throat cut. It wasn’t ear to ear, but she lay there just gurgling. It was awful. I was helpless. He just slammed the boot shut and I spun out. He told someone to drive her somewhere and just leave her in a dumpmaster. I got her dropped off at a railway station so someone would find her and take her to hospital. That saved her life.’ Or what was left of it. Sissy later committed suicide.

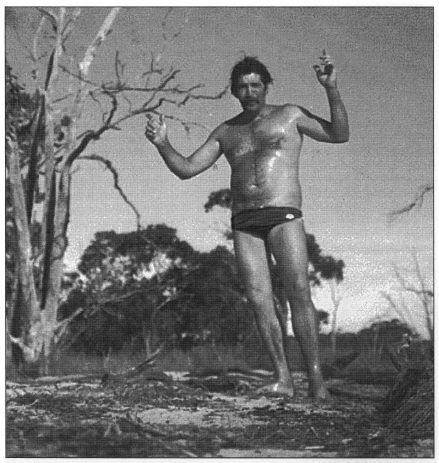

Neil Gordon Wilson … no one knows why he wanted to be a fish.

Neil Wilson self-portrait.

Neil Wilson self-destruction.

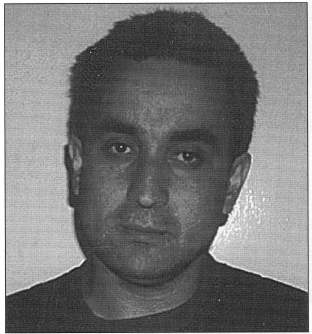

Kemal Sahin … wanted his wife’s finger delivered to him as proof of her murder.

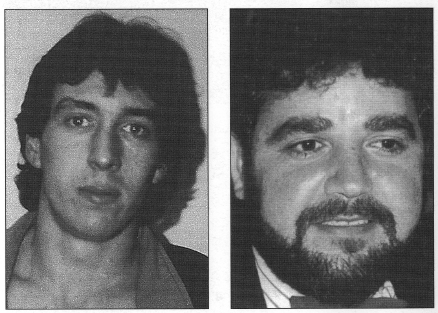

Victims of hitmen … Stuart Lance Pink (left) and Tony Franzone.

Eight more hit victims: Charles Francis Caron (left), Christopher Philips.

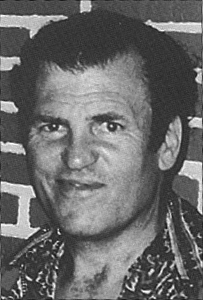

Dimitrious Nanos.

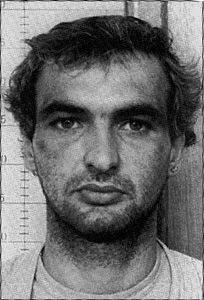

Quock Cuong Dwong.

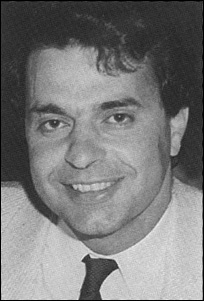

Alfonso Muratore.

Geoffrey Engers.

Santo Ippolito.

Rakesh Bhanot.

Double murderer and multiple rapist Raymond ‘Mr Stinky’ Edmunds.

Edmunds’ victims … Abina Madill and Garry Heywood.

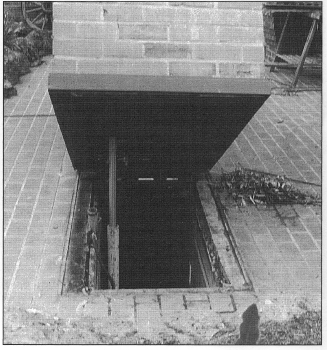

Bikie barbecue … hiding a massive concrete bunker used as an amphetamines laboratory in a suburban backyard.

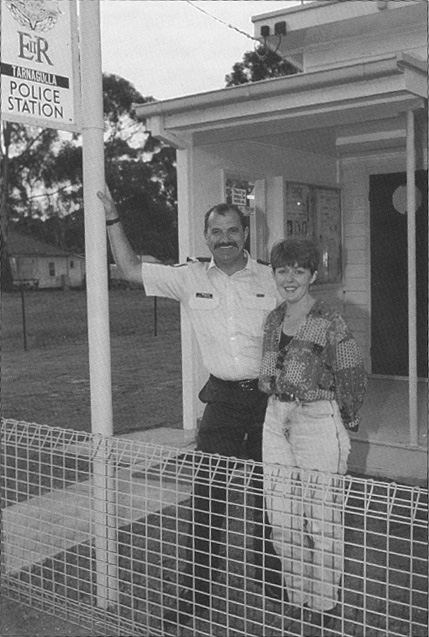

Jim Wiggins and wife Helen … the pressure of one-man policing led him to suicide.

On another night Allen brought home a woman he suspected of informing to police on a series of burglaries and car thefts. ‘He put her on a bed and beat her with a baseball bat. She was crying out for water and Dennis gave me some petrol and told me to make her drink it. When he went down the Cherry Tree (hotel) I sat her up and gave her some water and let her go. I just told Dennis she had escaped. I’ve got a heart. ‘Later, we were in the same cottage in jail and she said “Wendy, I can never repay you for saving my life”.’

While Peirce sees herself as the victim of her in-laws’ propensity for violence she was not kept there against her will. She was an active member of the family and accepted its peculiar ethos of rearing children in an environment of danger, police raids, drugs and death.

When Victor was arrested for drug trafficking in 1985, he wanted bail. Wendy, heavily pregnant at the time, purposely urinated while in court and announced to the stunned judge that her waters had broken and she was having a baby. Bail was granted.

‘I wouldn’t leave Victor and he was there. I was so young when I moved in with him and I adapted to what was happening. It was our biggest mistake moving into Chestnut Street. None of this would have happened if we had gone off on our own.’

A policeman who got to know her when she was in witness protection said: ‘She could be a real bitch. She had a savage temper and could flip out. She was sort of sucked into the gangster mentality of the family.

‘But she has a soft side as well, and really loves her kids. She came from a decent family but was drawn into their (Pettingill) way of life and had no way out.’

When she was in witness protection, one of the worst chores for police was to take her shopping. ‘She would shoplift things. She couldn’t help herself. She was always testing us, trying to push the boundaries.

‘She was in witness protection for nearly two years. I thought she had a real chance but it (the case) took too long to come up. She got in touch with Victor and that was the end.’

Another policeman is less sympathetic. ‘She is a manipulative woman who actively embraced the life of a gangster’s wife. She would do anything for the family and had the privileges that came from the profits derived from her husband’s drug dealings and armed robberies.

‘She agreed to go into witness protection when the family seemed to be disintegrating. It was a huge decision and she gave damning evidence at the committal. She was in protection for two years and she got sick of it. The family turned her again before the trial. If the trial had been quicker it may have been different,’ he said.

But Peirce denies having the trappings of the gangster days. She lives the life of a struggling single mother in an outer Melbourne suburb, struggling to pay the bills. She cannot use her telephone because of failure to pay previous accounts.

She says her children were victims of the family’s gangster background. ‘None of my kids have been in trouble with the law. Parents don’t want my kids mixing with theirs. What do they think? I’ve got a machine gun under the apron? I’m just a housewife.’

‘Katie’s a good kid, but she hardly ever gets invited to a birthday party. Another kid said at school the other day, “at least my dad isn’t in jail”.’

Peirce said a book about the Tynan-Eyre killings had been passed about at school. ‘I know the Walsh Street thing will never die down. I don’t care. I can live with that, but it is unfair on the kids.’

She said she knew that she had a temper and had convictions for crimes of violence. ‘I know I can get aggressive and fly off the handle but animals protect their young like mothers protect theirs.’

She said that all she wanted was for her husband to finish his jail sentence and come home.

‘He is the father of my kids but I’ve told him if this happens again that is the end. But it won’t happen again, I know it. When he gets out this time then that will be it. He adores his wife and children and he just wants to come home. We are just a normal family.

‘My daughter wanted to join the police force, but I told her to be realistic. There is no way known they would let one of Victor’s kids do that.’

PETER John Allen was a hard-working small businessman determined to get ahead. He had a product that was eagerly sought after, a strong distribution network and a captive market. His product was heroin, his customers were fellow inmates at Pentridge prison, and his supply line was managed by his half-brother, Victor George Peirce — one of the most dangerous criminals in Australia.

Allen controlled a large slice of the drug market to Pentridge, Bendigo and Geelong jails and he ran it using a telephone network inside the jail system.

Allen, then 41, was convicted of drug trafficking after a five-month trial costing about $960,000 in 1994. The jury of eight men and four women heard how a career criminal had been able to manipulate the prison system.

They were told Allen had made a total of $22,610 from 17 June, 1991, until 3 April, 1992, while inside prison.

According to police, he controlled a large section of Victoria’s main prison, using a combination of violence, drugs, a sinister reputation and cunning.

Allen had been convicted of being a heroin dealer in 1988 and sentenced to 13 years, with a minimum of 11. But for a career criminal, being in jail was only an inconvenience when it came to running a drug syndicate.

He developed a network using a corrupt prison officer, codenamed ‘The Postie’, three female couriers, five TAB accounts and his brother as his banker and drug buyer, all to supply inmates with drugs to order. The brothers trafficked heroin, amphetamines, Rohypnol and cannabis to prisoners.

In business; communication is the key, and Allen had no trouble talking to his outside network. He was allowed to work in the F division laundry, which he turned into a personal kingdom. He manipulated the system to the point where he had control of a telephone, which phone taps revealed he used to order drugs through an unsophisticated code and to ‘talk dirty’ to his girlfriends.

A group of prisoners worked in the laundry four hours a day. Allen used the telephone there for two hours a day. For a prisoner who should have been earning $20 a week, it was big business.

Police set up phone taps on the laundry phone and the telephone at Victor Peirce’s house to record conversations in which drugs and finances were discussed. The tapes were later used to break the network. As part of Operation ‘Double N’, police recorded 17,850 phone calls, including 1760 from the jail, and documented hundreds of hours of conversations.

During one phone call, Allen made it clear that it was he and Peirce who controlled the most feared crime family in Victoria.

‘Exactly. Yeah, ‘cause we’ve got it all together. Yeah, we’re the nucleus of the family. Yeah, we are the heart of the family, we keep things pumping,’ Allen said.

At one stage Allen lost contact visits for three weeks and rang Peirce in a rage. He asked his brother to organise the fire-bombing of several prison officers’ private cars as a payback.

He bragged on the phone that he certainly wouldn’t be broke when he got out, and spoke of paying ‘The Postie’ $300. ‘Not a bad effort for a poor boy in jail with 20 bucks a week … I’ve got people that want to help me out, that’s my business.’

As part of his business he organised inmates to get relatives or friends to deposit money (usually in multiples of $50) into one of the TAB phone accounts before the drugs were handed over.

The records, admitted in court, showed that cash deposits were made across Melbourne within minutes.

On 22 August deposits were simultaneously made to an account in the name of Peirce’s wife, Wendy, in Boronia ($50) and in Lonsdale Street ($52) at 1.49 pm. One week after that, deposits were made in Blackburn at 11.36 am and Balaclava two minutes later.

Police say Allen was able to control the network because prison officials put him in D division, an area for remand prisoners easily dominated by a man with Allen’s reputation. He had been placed there for his own protection from other career criminals.

In one telephone conversation he speculated whether the laundry telephone was tapped before dismissing the idea, believing that police might be monitoring his friend’s telephone: ‘His phone must be off.’

Detectives spent 13 months investigating Allen, from August, 1991, until September, 1992. Three months after the investigation began, Allen was transferred from Pentridge to Bendigo prison but he continued drug operations there. Police believe he also trafficked drugs while an inmate at Geelong.

‘We had no doubt that Peter Allen was a major drug trafficker within the system. He knew the system inside out and was able to build a network using jail telephones,’ the head of the Tactical Investigation Group operation, Detective Senior Sergeant Peter De Santo, said after the trial.

‘He was ambitious, and used hired muscle inside the jail to protect his business.’

The court was told that Allen had used five TAB accounts to hold the money. They included accounts in the name of Victor Peirce and Wendy Peirce, under her maiden name of Ford.

Allen bought a four-bedroom house for cash in 1985, after trafficking heroin for only four months after his release from jail.

According to fellow prisoners, Allen is intelligent, with a good grasp of the law, and has often acted as his own defence counsel. In the latest case he used a barrister paid by legal aid, but it did him no good. The jury took less then a day to find him guilty.

While Allen could be ruthless, prisoners said he lacked the violent streak of some other members of his family.

Victor Peirce did not confine himself to dealing in drugs for his brother. He also ran his own syndicate on the outside. In a separate case he was charged and convicted of heroin trafficking and sentenced to eight years with a minimum of six.

The Office of Corrections has changed the telephone access rules for prisoners, allowing inmates to ring only four different approved numbers. But drugs are still getting into every jail in Victoria.

Kathleen Pettingill: Former barmaid and massage parlour madam. Heavily connected in the underworld for 20 years, she had one eye shot out by another woman in 1978. Police codenamed an investigation into the family ‘Operation Cyclops’, a sly reference to the one-eyed giants of Greek mythology. Has written her memoirs, The Matriarch. Had six sons and a daughter, all with criminal records. Two have died.

Dennis Bruce Allen: Kath’s son. Drug dealer, murderer, pimp, police informer, and gunman. Allen was investigated over 11 mysterious deaths in the 1980s. Was believed to have been protected by corrupt police. Was making between $70,000 and $100,000 per week from drugs. He was on bail for 60 different offences in the early 1980s. He would inform on criminals to keep out of jail. Died in 1987 from heart disease. One death notice read: ‘Dennis the Menace with a heart so big. Sorry you’re gone, you were such a good gig.’

Peter John Allen: Kath’s son. Probably the most intelligent of the family. Considered one of the best ‘jail house lawyers’ in the state. Has often defended himself in complex criminal trials. Ran a heroin empire while in jail using a corrupt prison officer code named ‘The Postie’, three female couriers, five TAB accounts and his half-brother Victor as his buyer on the outside. In custody on drug trafficking. Release date, July 1999.

Victor George Peirce: Kath’s son. String of convictions. Charged and acquitted of the Walsh Street killings. Involved in armed robberies and drug trafficking. His best friend was Graeme Jensen, who was shot dead by police on 11 October, 1988. Has four children. In custody on drug trafficking, release date, May 1998.

Wendy Margaret Peirce: From a respectable South Melbourne family. Was to give evidence against Victor over Walsh Street but later changed story. Convicted for perjury. Says her life of crime is over.