Exit

NEXT TO A RED HILL in the desert, our only daughter wandered and disappeared into the thicket of her dreams, leaving us blind—as we heard the thud of her fall without knowing in which direction to turn.

1.

NELLY WAS THE first to pick up on it. One night, after Shira had fallen asleep, she whispered to me in the kitchen that something was going on with our little girl. Something bad. Not just your everyday blues. Something in her eyes had changed since we moved south. “I’m not speaking metaphorically,” she stressed. “There’s something in their grayness that doesn’t look right. I don’t know.”

Nelly believed in the body, believed it spoke louder than words. She claimed that’s how she could almost always tell when something was about to happen to Shira. I thought there was a simpler explanation. That she always suspected something was going on with our daughter, so sometimes she also happened to be right. I’m not saying this as criticism. Quite the opposite. Nelly was the better parent. Neither of us doubted that. When Shira was five, even she noted in a passing remark made on Tel Baruch beach that “Mommy loves me more.” Nelly quickly denied it, signaled to me to go get the girl an ice cream, and like an idiot I ran a kilometer and a half for a cracked Cornetto, only to run back and discover that a week earlier, Shira had sworn off dairy because her kindergarten teacher said milk was stolen from cows. I don’t know whether Nelly forgot to warn me, or if she just wanted to remind me of the power dynamic. I, for my part, tried to come out ahead at least in the more banal areas—parent-teacher conferences, school plays, and sports competitions—where I enjoyed a slight lead. This included the fourth-grade soccer league’s final match of the season, when ASA Ramat Aviv beat Beitar Kfar Shalem two to one thanks to Shira blocking a last-minute penalty kick.

A brief hug at the end of the game. That’s all I managed to get from her.

“The girl’s doing fine,” I announced. I told Nelly that I had actually been worried the first two weeks, when she acted as if nothing had changed. No sane girl moves from Tel Aviv to a desert homestead without having some kind of temporary crisis, and it’s good for her to finally experience it.

Nelly said I was missing the point and lowered the jar of herbal tea onto the table with a thud. Other than her clothes, it was the only thing she brought with her from our old house, claiming that without it she would go back to smoking in two days. I wasn’t as successful at asceticism; I set out south with two bookcases, a telescope, and my framed certificate of excellence from the Technion, which I still haven’t found the time to hang. It was the one condition I made when Nelly insisted we move, to take whatever I wanted with me, and to her credit she never gave me any trouble over it.

“It’s a little more serious than that, Ofer,” she said, adding my name to convey the gravity of the matter.

“You’re just getting yourself worked up for no reason,” I threw in before she could say anything else. “Give it a couple of weeks, the girl will get used to it.”

“That’s what I’m trying to explain, I don’t think it’s just the move,” she said, and added in a confiding tone, “Maybe you could talk to her? I’ve tried but it’s not working.”

I wanted to say that I’d tried as well, that I’d been trying for some time now and getting nowhere. And that also, I’d lately come to realize that Shira had always belonged more to her than to me. That maybe it was time we considered having another kid. And that we would agree that I get dibs on this one. We’d sign an agreement before he’s even born, two kids for two parents. But I didn’t really want to bring up the subject, to deal with her adamant assertion that it was all in my head, and her not-so-subtle insinuations that even if it wasn’t, a father doesn’t talk about his child like that.

“Sure thing,” I replied, got up, and went to our bedroom. “I’ll talk to her.”

2.

I WOKE UP to an empty room. Nelly had left for work early and dropped off Shira at school on her way. She was supposed to start work every day at nine, but insisted on being at the office at eight. To set an example. “To help these people realize their potential, because potential is not something they’re short of here in the south,” she’d repeat her worn mantra, as if the people of the south were another moisturizer she had taken upon herself to market to the masses. I have to admit I was skeptical at first. When out of nowhere Nelly suggested we move to a remote farm in the south, I didn’t buy her sudden Zionist urge to settle and develop the Negev. But after two months here, I’m not so sure anymore. You never know with Nelly. Most of the time she can’t stand the world, but every so often she gets these bursts of compassion, which she herself can’t explain. She once called me from the car, and sounding rather distraught said she had picked up a homeless Russian she found on the street. She ordered me to switch on the water heater and clear my wet clothes from the bathroom. Only after I said that if Shira caught AIDS it was on her did she come to her senses, dropping the guy off on the Namir highway with two hundred shekels in his pocket.

And yet, Nelly wasn’t one to move to the south out of purely altruistic motives. It’s tempting to believe we moved because she wanted the promotion, but that wasn’t the only reason either. Even though we never discuss it, I know we moved because of me. Because I didn’t deliver. Didn’t make good on the promise I made on our first date in that dive bar in downtown Haifa.

During our twelve years of marriage, how many times have we discussed that promise? Three? Four? Hard to say exactly. But I do remember what she told me a few months after that first date, when we went on our first vacation together—a bed-and-breakfast in the Galilee. She lay on the bed in a white bathrobe, half naked, ran her fingers through my hair and said that was what had won her over. The promise that by forty, I’d make my first million. She explained it wasn’t my desire to get rich that attracted her. It wasn’t the money, it was the drive. It was how I said it—not as an aspiration, but a cold fact. “That’s what makes you so special,” she said, and quickly added, “makes us special. The drive to push forward. To succeed unapologetically.”

I immediately told her she couldn’t be more right. And not because I actually knew she was right like I was hoping she was. I don’t know whether I was truly planning on making a million bucks, or just wanted to impress a girl. But with time, I found out I liked playing the guy she wanted me to be. The one who goes once a week to a fusion restaurant without knowing what fusion cuisine means; who surprises his girlfriend with a trip to London on a Wednesday morning for no special reason, just because he feels like it. Nelly says a man is measured by his most ambitious dream, and mine started the day I met her.

There was only one problem with our dreams—she realized them, and I didn’t. She beat me four years ago, whizzed past me leaving a trail of dust when she was appointed VP at Segal & Zuzovsky, while I was still stuck in career limbo as a development manager in a series of mediocre start-ups whose idea of a company fun day was an egg-and-spoon race at the Yarkon Park. At first she teased me that I couldn’t keep up. But with time the banter died down and was replaced by tedious exchanges such as whose turn it was to take out the trash and which form to fetch from the bank. Petty requests that only reinforced my fear that all the expectations she had of me at the beginning had disappeared along the way, as if she had resigned to spending her life with a lesser man.

I honestly thought the start-up I had joined two years ago, Lucid Memo, was going to change everything. The whole business was based on a Jewish professor of neuroscience from Harvard who immigrated to Israel after reading the book Start-up Nation. She moved here and hooked up with an Israeli hi-tech entrepreneur, some guy called Amichai Miner; they decided to devise a technology that would enable people to share memories. Today I can’t believe I thought it stood a chance; I guess I just didn’t think it through at the time. I even gave up part of my salary in exchange for options in the company. All I wanted was to make good on my promise. To score a knockout against life itself. I worked my ass off, anywhere between fourteen and sixteen hours a day, including weekends. Including holidays. More than I wanted the money, I wanted to get to the moment I could tell Nelly I made an exit, that the company was sold to some Chinese investment fund. To see how she would smile despite herself, exposing that small gap between her two front teeth she always tried to hide.

But that didn’t happen. Development stalled and the money started to run out. I was forced to recruit mediocre talent because we couldn’t compete with the salaries other companies were offering. Six months later I was fired from my position as head of development, and one of those unremarkable employees took over my role for half the pay. His name was Nicolai, a strange bird who had graduated from college only three years ago; one of those people who thinks that anyone who doesn’t vacation abroad at least once a year is living below the poverty line. He still calls me once a month to bitch about his problems at work, failing to comprehend that I have no interest in helping him, even though I’ve been laying on pretty thick hints about it.

Anyway, instead of celebrating my fortieth birthday on a yacht bound for the Canary Islands like we’ve always talked about, Nelly and I settled for Eyal Shani’s new joint. Rockstar Shlomi Shaban and his actress wife, Yuval Scharf, sat at the table to our right. It was there, shortly before our dessert arrived—chocolate cake sprinkled with sea salt—that Nelly brought up the idea of moving south. “For half a year tops.” She said Zuzovsky had asked her to set up the new offices in Mitzpe Ramon. She talked about the unexploited potential of the residents of the Negev. She said that if she did a good job, she’d climb another rung on the ladder to CEO. And that the timing couldn’t be better because her parents would be staying in LA for at least another year, so we could live on their farm on Highway 40, a fifteen-minute drive to Mitzpe. Then she launched into a ten-minute monologue about why living at the end of the earth was actually a good thing. That the clean air would do wonders for Shira’s asthma. That we always said we wanted to check the living-outside-a-major-city box. And besides, it would be significantly cheaper living on the farm because her parents were even paying the electricity and water, so instead of looking for a new job I could work on developing that app I’d been talking about for over a year now. And what she really wanted to say but chose not to was that it had been two months since I’d been let go and I still hadn’t gotten off the couch. That if I wanted to continue being unemployed and depressed, at least I could do it in rent-free shitsville.

I didn’t actually need much convincing. Back then, all I wanted was to take a breather. To stop for a moment and figure out what my next step should be after failing to accomplish my one goal.

“No chance,” I replied. I argued the move wouldn’t be good for Shira. That I couldn’t see myself living outside Tel Aviv. I was afraid of telling Nelly the truth because I had the feeling she might be testing me. That she was thinking of leaving me and checking where I stood. So I said there was nothing to talk about, and only after two weeks, when I realized she was serious, did I say I’d do it, just for her.

Shira was psyched about the idea, said living in the desert sounded like a dream. She thought and talked about the world in Disney terms, and meeting her expectations wasn’t always easy. She once declared hysterically that she had to find the star closest to the sun otherwise she’d die, forcing Nelly to take her to the observatory in Givatayim that very same evening. When she was eight, she reached the conclusion that she was a secret princess and we were her adoptive parents, thinking the word “adoptive” meant evil. Her first attempt to run away from home soon followed. We found her seven minutes after she walked out the front door, fifty meters from our building. She told us she hadn’t dared go any farther because she knew she wasn’t allowed to cross the street alone.

We didn’t always know how to handle that distant dreaminess of hers, and she certainly didn’t know how to handle our sarcasm. She kept saying she’d never be like us when she grew up. On her most recent birthday, when she turned eleven, she even tried hiding the Encyclopedia of Fairies she got from her friend, fearing we’d tell her fairies weren’t real.

Nelly worried Shira wouldn’t fit in at the school in Mitzpe. She claimed that if Shira couldn’t even handle us, she wouldn’t stand a chance with the children there. They’d eat her alive. I was also afraid the hooligans of Mitzpe would crush her delicate soul, but I thought it was a good opportunity to force her out of her little bubble. Luckily, she landed a good teacher, who even assigned her a “big brother,” a year ahead of her. When Shira got home from her first day at her new school, we were on the edge of our seats as if she was returning from the front lines and had lived to tell the tale. Straight off the bat she said we had lied to her, that the kids in Mitzpe listened to exactly the same music as the kids in Tel Aviv, and we both laughed with relief.

Unlike for Shira and Nelly, no one was waiting for me in the south. To be honest, it was a comforting realization. I thought that at first I’d spend most of my time herding sheep, connecting to nature or something like that. But after two days I realized that Nabil, the Bedouin worker who tended to the farm, did everything much better than I ever could. I only got in his way with my silly questions. So after a week of dragging my feet, I decided Nelly was right, that it actually was a good opportunity to start working on my app. I had gotten the idea for it when I was still working for the last start-up; one of the employees at the office had said his dream was to buy a Ferrari, but he had no idea how to even start saving up for it. It got me thinking there could be an app that helped people realize their dreams. You’d type in the thing you wanted most—a Ferrari, a house in Petah Tikva, a monthlong trip to Japan—and the software would calculate your odds of fulfilling that dream based on data such as the price, your salary, and current expenses. And not only would it evaluate the odds, it would also provide an estimated time frame and suggest the necessary steps toward getting that Jet Ski you had always wanted. It would recommend small changes to your spending habits, such as canceling your gym membership that was just a waste of money, or skipping a vacation in Greece. Every so often, the app would even recommend more significant life changes. For example, weighing the possibility of quitting your job as a high school teacher against cashing in on your charisma as a real estate agent. Because values are nice, but then you have only a 4 percent chance of being the proud owner of a Ferrari.

I started spending a few hours a day working on my idea, running market research to see if a similar product already existed, making phone calls to people who could help me get started, trying to write a rudimentary code for the software. I can’t say exactly what I did, but I can say it took up most of my time. When I think back on that period, it feels like a faded, dragged-out dream devoid of clear actions. The only thing I remember clearly is that other than working on the app, once a day, a little before sunset, I’d climb up the hill behind the farm and look at the lights coming on across the Mitzpe below.

The official name was “Tel Ahmar”—the Red Hill. But it wasn’t really red, just a sandy hill in faded shades of brown. And it wasn’t even a hill but a cliff someone had probably fallen off once. No one sets out to visit Tel Ahmar. Most people stumble upon it on their way to Eilat. They climb up the hill and come back sweaty and tired, asking me where the red sand was, to which I reply with the same tired joke that it just ran out an hour ago.

3.

THE DAY AFTER my conversation with Nelly, Shira came home in the afternoon like always. She shut the door behind her, holding a small hoop with colorful threads and beads.

“What’s that?” I asked.

“An Indian dream catcher,” she replied. I asked who gave it to her, and she said her big brother.

“Nice of him,” I said. “Sounds like he likes you.”

She blushed, but didn’t answer. Didn’t even smile. I immediately wanted to change the subject, feeling bad for embarrassing her. I asked if she wanted me to make her something to eat. She said she didn’t, which was a relief because there wasn’t enough food in the fridge to whip up something nice. I knew I had to talk to her, but didn’t know how to begin, and before I could find a way she was already in her room. I stood by her closed door for several moments, then reached out to knock, but the fear that she wouldn’t open got the better of me.

I had already come up with the alibi I’d give Nelly, that I hadn’t talked to Shira yet because I had to help Nabil tend to an injured sheep. But luckily, I didn’t have to lie. Nelly had had a long day at the office and only came back to the B&B around midnight. That’s what Nelly and I called the place we lived in, simply because we were unable to call it home. Nelly collapsed onto the mattress without brushing her teeth. Her parents were short, thin people who made do with a narrow double bed. Like every night, we embarked on a long session of awkward fumbling and shoving in an attempt to find a semi-comfortable sleeping position. And I, even though I never told her, liked the small shoves that sometimes turned into brief caresses, intimations of the obscure distance between us.

In hindsight I can say the dream catcher was the first sign, but as with the others that followed, I failed to take notice. That bus she missed, the bleary eyes, that morning I woke her up and for a moment she didn’t recognize me. A litany of supposedly random events that only revealed their full meaning with time.

4.

“A TIP FOR LIFE.” That was the headline of the newspaper article I had been reading the day it all began. It was about a waitress in the States who received a ten-thousand-dollar check from an old customer, who then killed himself by jumping off a bridge and into the Mississippi River. I hope that before I die someone will solve the mystery of why our minds remember such useless information. Every evening I’d wait for Nelly to bring a copy of Yedioth Ahronoth from Mitzpe. I used to wrap it in a blue plastic bag and put it on the table, saving it for the next morning. Nelly reminded me that I was already reading it after everyone else and didn’t see the point of putting it off even longer, but I had started to like the idea of living in a different time zone from the rest of the world, a day after everyone else. I liked thinking that when time took a right onto the dirt trail by Highway 40, it came for a little R&R. That here it stopped moving forward at a steady pace, knowing that it was allowed to slow down, even move a few minutes backward, sag, or spill sideways.

I don’t remember seeing her walk in. When I raised my head, Shira was already inside the B&B, hanging her black backpack on the hook by the front door.

“Hey, you’re back,” I said.

“Yup.”

“How was school?”

“Fine.”

“Good. Did you learn anything interesting?”

“Not really.”

We were silent for a few moments.

“Want something to eat?”

“No.”

“Are you sure? I can make you a sandwich.”

“I’m sure. Thanks.”

“Okay. Do you have homework?”

“A little.”

“A little is good,” I said. “Time to do it?”

“In a minute.”

“Good, good.”

I went back to the newspaper. Out of the corner of my eye I saw she was still standing there. I looked up and smiled, asked if everything was all right, thinking it might be a good moment to try talking to her. She said everything was fine and even smiled. A small, brief smile. She turned toward her room and I let her go, keeping my eyes on the newspaper even though I couldn’t really concentrate. Five, maybe ten minutes later, I heard the keys rattling in the lock. Nelly had a dinner meeting with a potential client, so she had come home early to get ready. She opened the door and took two steps into the B&B. She dropped her bag and crouched down. For a moment I thought she had fallen, but then I realized—Shira had been there the whole time. Sitting in the corner, by the door, and I hadn’t noticed. Sitting with her back against the wall, her arms slumped to her sides. Her gaze was fixed to the floor, to a nondescript point in space.

“Shirale, what are you doing here?”

“Nothing,” she said.

“How long have you been sitting here like this?”

“I don’t know.”

Nelly looked at me, waiting for an answer.

“Five minutos,” I said in our made-up hybrid of English and Spanish, a secret language Nelly and I tried to invent to replace the Yiddish and Moroccan our grandparents spoke between themselves.

“What’s going on, Shira, tell me,” Nelly said to her.

Shira didn’t reply, and I was getting anxious, my mind racing with a thousand and one frightening scenarios.

“Come on, Shira, explain it to us,” I said.

“We need to understand what happened,” Nelly added.

“I’m fine, really,” she replied with a feeble voice.

“Shira, up, come on. This is no good, sitting on the floor like this.” I took two steps toward her.

“Let’s move you to a chair, Shirush?”

Shira shrugged her shoulders with reluctance.

“So maybe you and I should go for a little walk?” Nelly suggested.

“Maybe,” Shira replied.

“Good, that’s a great idea,” I said. “We’ll go out, get some fresh air.”

I bent down to lift her, reaching out both my hands. Shira averted her gaze, and Nelly grabbed my hand. There was something rigid about her touch.

“I forgot to tell you, Nabir wanted you to go help him.”

“What?”

“Nabir said he needed you, that there’s a problem with the sheep’s water tank. Do me a favor, go to him.”

“You mean Nabil?”

“Yes, yes. He said it was urgent. Would you go already?”

“But, la niña,” I protested.

“Don’t worry, I’ll stay with her.”

I froze.

“Well?” she urged me, her tone slightly raised, just enough so I’d get the hint but Shira wouldn’t. I don’t know why I agreed, but I went outside. Nabil was sitting by the sheep shed, wearing a hat with the logo of an insurance agency and smoking a Noblesse. He was a big guy who could barely squeeze himself into the white plastic chair. I walked up to him and sputtered, “What’s this business with the water tank?” He had no idea what I was talking about. I explained that Nelly said he was looking for me. He still didn’t know. I told him it made no sense, because we were just in the middle of something with the girl.

The worst thing was that Nabil figured it out before I did. He understood Nelly had wanted me out of the way.

“Okay, a miscommunication, I guess,” I said in a pitiful attempt to save face. “I’ll head back.”

“Wait,” Nabil said. “Your Nelly is a smart woman. That one knows what she’s doing.” He removed the bag resting on the chair next to him. “Sit, habibi, sit,” he said and took another cigarette out of the green pack.

I hesitated for a moment, but sat down.

“Trouble with the girl?” he asked, and I nodded. Nabil took a drag and looked out at the red hill. “There’s nothing worse than a man standing helplessly in front of his children,” he announced. “Wallah, there really is nothing worse.” He turned his gaze to the B&B, watching Nelly opening the front door, folding her arms and looking out at the road. I heaved myself up. “Good luck,” Nabil said and smiled. “Or like they say, break a leg.”

She apologized before I even reached the doorstep. “I don’t know, I was hoping that if just one of us was there it would lower her resistance threshold,” she said, quoting yet another term she had picked up from the child psychology books she liked to read. “I couldn’t get anything out of her,” she sighed. “I don’t understand what’s going on with her, I really don’t.” She leaned her head against my chest, instantly dissipating my anger. “We’re in over our heads, Ofer. She needs to see a professional.”

“What do you mean a professional? A doctor?” I asked.

“A psychologist, an art therapist, I don’t know,” she said. “Someone who can figure out what’s troubling her.”

At “psychologist,” I thought Tel Aviv. An opportunity for a visit on the grounds that psychoanalysis had yet to find its way south.

“I’ll text Sagi, he sees a psychologist on Dizengoff Street, says he’s excellent.”

Nelly laughed. She said Dizengoff was a three-hour drive, but she could compromise on Beersheba. She said that since I was already going to be there, it might not be such a bad idea to get some therapy myself. “Having an intimate relationship with a city that boasts over seventy percent humidity is not normal,” she said, and I laughed. She was like that, could placate me with just a few words after days of estrangement.

5.

THE PSYCHOLOGIST STOPPED the session after half an hour. She came out into the waiting room, caught me napping with an eye half open, and asked if my child was on the autism spectrum.

“Of course not,” I replied before even processing the question, and quickly straightened my back.

“I think you need to take her to the hospital,” she said, explaining that there was no point completing the session since the child was barely responsive. That it wasn’t a psychological matter but a physical one. Neurological, in her opinion. “You haven’t taken her to a doctor yet?” she asked with subtle reproach.

I tried defending myself. I said Shira was pretty much a happy girl, but the psychologist opened the clinic door and said, “See for yourself.” I approached Shira and put my hand on her back. I asked her how the session was going, but I could already see she wasn’t the same girl. Sitting cross-legged, her head drooped like a rag doll’s, her brown hair veiling her face. She wouldn’t look me in the eye, replied curtly, three words at a time.

I waited with her for two hours in the ER until they took her for a diagnosis. A young intern asked her a series of questions, but she wasn’t cooperating. He checked her pupils with a flashlight, then her reflexes. He didn’t detect any abnormalities. He called over a doctor who also didn’t find anything unusual, and whispered to the intern that something didn’t add up. They decided to admit her for further tests.

Nelly freaked out when I told her. She left the office at once, took a car from one of the employees, and raced over at 130 kph. She arrived after Shira had already fallen asleep, sat down on the chair next to me, and rested her head on my shoulder as I gave her a detailed report.

“What have we gotten ourselves into, Ofer?” she whispered, and I recalled another night, a few years back, when she had leaned her head on my shoulder like that. It was after she had gotten drunk on half a bottle of cava and admitted for the first time that she had changed her name from Nili to Nelly because Nili was an old woman’s name and Nelly sounded like a Canadian supermodel. I remembered laughing my head off while she dug her face into my shoulder with childish embarrassment.

In the morning Shira underwent a neurological examination that came out normal. Additional tests over the next few days also failed to provide any answers as to what had happened to our daughter. Nelly went back to the farm that first night and I slept on a chair, but once we realized Shira was going to stay in the hospital a little longer, we decided to pull shifts. Nelly took the evening ones, straight from work, and I took the rest. It was clear to us both that I was suspending all work on my app until things cleared up. The doctors told us the symptoms weren’t caused by trauma, but the facts didn’t interest us. We were consumed by our fears, dedicating our few moments together at the hospital between shifts to our ever-expanding list of suspects without knowing what the indictment was. That “big brother” of hers from school. The bus driver who picked her up every morning. Her teacher. Even Nicolai, my former coworker, had become questionable. Names were added, others temporarily removed, but one always remained, hovering at the top of the list.

Say, is it possible that we left him alone with Shira on the farm? Why is he always working so late? And what’s he always fiddling around with behind the B&B? Yeah, and how can he even afford that pickup of his? And why won’t he stop asking how Shira is doing? What business is it of his?

I didn’t actually think Nabil had done anything to Shira, but there was something comforting in the thought of having an address to direct our pain.

Together, Nelly and I had come to the conclusion that something about his big body was a threat. She wouldn’t stop saying that we were smart never to have asked him in for coffee. At first she stated repeatedly that our suspicions had nothing to do with him being a Bedouin, but then she stopped. Said that the whole situation with Shira left her too tired to deal with it, but if she had any energy she would have told him long ago to leave. That living with all the question marks surrounding him was simply impossible. Nelly didn’t ask for anything explicitly. Didn’t even hint, but I understood it fell to me to take care of it.

Three or four days after Shira was hospitalized, after snatching a few hours of sleep on the farm, I headed back to the hospital so Nelly could go to work. On my way out of the B&B I saw Nabil. He was sitting by his pickup, pouring himself coffee from his orange thermos. He took out half a pita with hummus wrapped in tinfoil and waved at me. I thought I’d put off the conversation for another day, but he gestured me over, leaving me little choice.

“Sabah al khair,” he said, and quickly poured coffee into another small glass. “Tafaddal, ya Ofer, tafaddal.”

I told him I didn’t want any. “Haven’t started working yet?” I asked, trying to mimic the psychologist’s disapproving tone.

“Two hours ago,” he replied. “Sugar?”

Again, I said I didn’t want coffee.

“That’s a shame, it’s good for the soul,” he said. “Tell me, how’s your little girl?”

I informed him there was no improvement. The doctors couldn’t figure out what was wrong with her. Nabil put his hand on his wide chest, his eyes welling up.

“Wallah, what a tragedy,” he said in a strangled voice. “Why did this happen to us, why?” he exclaimed, trying to comfort me, which only drove me crazy. With a single word—us—he had appropriated my only child. I couldn’t stand the thought that just like that, from a few physical gestures and even fewer words, he had expressed everything I wanted to feel but couldn’t.

“If you want me to come to the hospital at night to help out, just say the—”

“How about keeping your nose out of it?” Nabil quickly apologized, said I was right and the offer was inappropriate. He took a last sip of his coffee, got up, and announced he was going back to the sheep.

“Listen, Nabil, since we’re already talking,” I said, “Nelly and I have given it a lot of thought lately. We realized we don’t need that much help with the farm.”

Nabil washed out the glasses with a squished water bottle. He smiled.

“Obviously, I need help, not you,” he said, and burst into laughter.

“I mean, we don’t need your help.” I saw the lines on his face tensing. It wasn’t the first time I had fired someone. The face always does that. People walk around their entire life trying to be unique, but the moment they lose control, the body takes over and they all react the same way. Nabil put down the bottle and glasses on the chair, rubbed his hands on his jeans, and looked at me.

“You don’t need help?”

“That’s right,” I answered.

“Wallah,” he said. He clenched his right fist and took a deep breath.

“What is this? Where is this coming from, huh?” he said, raising his voice. “Did Nelly’s father say you could do this? I work for him, not for you.”

“Yes, we’ve talked to him, it’s all been approved,” I lied. Nelly could deal with that one later. His wide frame froze. The possibility that Nabil was innocent evaded me at that moment, making way for the thought of Nelly’s smile once I told her I’d dealt with it.

“You know that soon it’ll be seven years that I’ve been working here? Back when the Bezalels were here, before Nelly’s father bought the place,” he said, and what he meant was long before some retired bank CEO bought himself a farm in the south because he didn’t know what to do with all that money.

“Seven years is a long time.”

“A very long time,” he replied, his voice stifled with insult.

“You’ll get your full compensation, don’t worry. You can leave with a clear mind.”

“Oh, I’m not worried, believe me,” he said, twirling the water bottle with both his hands. “Just tell me, Ofer, who’s going to take care of them now?” he asked, pointing the bottle in the direction of the sheep. Tiny beads of water spilled onto his black rubber boots. “You?”

“Yes,” I said. “Me.”

“You?”

“Aywa,” I replied in Arabic. Nabil laughed again.

“Wallah? What can I say, habibi,” he said, and placed his sweaty palm on my shoulder. “Good luck with that. Really, good luck.”

Nabil collected the thermos and glasses, turned, and placed everything in the passenger seat of his pickup. I quickly got into my car and saw in the rearview mirror Nabil trailing along the dirt road in the direction of the highway, laughing to himself.

I made it to the hospital an hour and a half later. “You don’t need to worry about Nabil anymore,” I told Nelly, explaining that I had fired him. She smiled and caressed my cheek, reminding me how gentle hands could be. I spent the entire day with Shira in the presence of that smile, toying with the idea of a start-up that would develop the technology to preserve touch the way you save a photo, so that whenever I wanted, my brain could re-create the exact sensation of her hands at the click of a button. I asked Shira what she thought of my idea, but she didn’t even answer. When Nelly arrived in the evening Shira had already fallen asleep, and she said we might as well both sleep at the farm tonight. It wasn’t as if the girl was in any real danger, and in any case she always slept through the night.

“She won’t even know we weren’t here. We could put up a scarecrow with a picture of my head and it would be enough,” she said. “Actually, it would probably be enough even when she’s awake.” For a moment we hesitated about whether we were allowed to laugh. We decided we were, but only a little.

That night Nelly and I had sex like we hadn’t had for a long time. The narrow bed continued to close in on us, but also pushed our bodies into each other. Hands to face, lips to neck, feet to knees, eyes to stomach, with no room for unnecessary distance. And everything with swift, precise movements, because the mattress wouldn’t allow otherwise.

“We look like a Picasso painting,” Nelly said, to which I replied, “Totally,” and we smiled at each other because we both knew I had no idea what that meant. Afterward, with her head resting on my chest, it occurred to me that maybe it was better this way—better the girl suffered a bit longer if that meant I would get my Nelly back. But I immediately told myself I was just being foolish, and that the most important thing was that the girl got better. So if one day they invented a machine that read minds, no one would know I had wanted my girl to suffer.

6.

THE DOCTORS DISCHARGED Shira from the hospital after a week, saying that maybe being at home would help her find her way back to herself. The only problem was that the B&B wasn’t a home. Not to us, and certainly not to Shira.

“Maybe we should move back to Tel Aviv?” Nelly suggested in the corridor, next to the vending machine. She said she’d probably have to quit her job but maybe that wasn’t such a bad thing, that it shouldn’t take her more than a month or two to find a new firm. She was surprised I was the one who insisted on staying.

“Another move is hardly what the girl needs right now,” I said. “And if I go back to work, who exactly is going to take care of her?”

Nelly nodded, finding my reply reassuring, happy she didn’t have to feel like a career-crazed woman. Shira spent the entire ride home sitting in the back seat staring out the window. When we arrived, she unbuckled her seat belt and opened the car door even before I’d switched off the engine. She got out of the car and started running toward the red hill. We were so excited by that sudden display of animation that we left the keys in the ignition and ran after her. She was moving with incredible speed while we panted behind her, laughing that we could barely keep up, then arguing who she had gotten her athletic genes from. And I started thinking that maybe it had all just been a bad, absurd dream, that by tomorrow the girl would be back in school, maybe even cashing in on her classmates’ empathy to win the election for student council.

My hopes were dashed once she made it to the top and immediately collapsed onto the ground. She lay on the sand, arms splayed, staring at the sky. We called out: Shira, Shirale, Shirush. We tried everything, but she didn’t answer. It took us an hour until she agreed to get up—or more like didn’t refuse. On the way down, we held her on either side so she wouldn’t fall. We led her to her room and laid her on her bed, quickly tucking the blanket around her, as if it was a straitjacket that would protect her from herself. That evening, Nelly told me she didn’t know what she would have done without me. That she didn’t know any other man who would take upon himself running a farm with forty sheep and one fading child. She admitted it was hard on her, too hard. That she couldn’t bear to see her little girl falling apart before her very eyes. And just like that, with one brief sentence, she shifted the responsibility for our daughter’s care over to me.

It began with the typical tasks, putting her to bed at night and making her three hearty meals a day, but very soon it became clear it wasn’t enough. Because the girl was barely functional, the circumstances demanded more: help with brushing her teeth, changing her clothes, and taking her on daily walks to the hilltop became an integral part of the job description. And I, who thought I had already missed out on Shira, had gotten a second chance to raise her.

Only tending to the sheep turned out to be a much more complicated task than I had imagined. The one time I tried leading them to the nearby meadow it took me the whole day and I lost two sheep along the way. After that little incident, I decided I ought to keep them within the perimeters of the farm, convincing myself they didn’t actually need anything other than food and water. And even if they did, they’d manage. Nabil had left his white plastic chair on the farm, and Shira liked sitting on it and looking at me while I fed the sheep. Sometimes she’d start laughing when she saw what a miserable mess I was making of it, and I’d look at her, hoping she’d never stop. I was the only one who got to see those bursts of life. Those few brief moments, once or twice a day, when the girl smiled or even spoke, emerging from her burned-out soul. One morning, on the hilltop, she said she liked breathing in the desert. And one evening, she asked for another omelet. Said she liked it best when I made it with onions. Nelly didn’t believe me, said she needed to see it with her own eyes. I told her that’s what drove me crazy; it was one thing if the girl had disappeared completely, but it was clear that beneath it all, Shira was still there.

Two weeks later, Nelly took the girl for a checkup in Beersheba. She offered to drop me off in Mitzpe, so I could take a break for a few hours, get some fresh air. I didn’t want to, but Nelly insisted and while she didn’t come out and say it, what she meant was that she needed me to take a break so she’d know she was allowed to as well. Because the conference in Tel Aviv was in two weeks’ time, and she needed to know it was okay for her to go away for three days.

I gave in, and a moment after she dropped me off at a café, I crossed the street and sat down on a bench as an act of protest. So no one could say I was having a cappuccino while my little girl was having an MRI. But soon enough the Mitzpe sun bested me, forcing me to get up and embark on a quest for the last remnants of shade. Passing by the public library, I negotiated a compromise with myself—I’d sit in the air-conditioned space only if I spent that time trying to figure out what was going on with Shira. It was a small library with a frayed green carpet running the length of the floor, gray steel bookcases lining the walls, and a librarian wearing sunglasses and holding a white cane pacing back and forth by the front door. I wanted to go on the internet, but a few kids who had skipped school were sitting at the only computer station. The kids ignored my presence completely, and I found it rather pleasant thinking I was both there and not there. I spent three hours skimming through all the medical books stacked on the shelf beside the reflexology and shiatzu books. My mind was spinning with the countless illnesses that could have attacked Shira; the various ways in which a person can simply cease to exist were truly unfathomable. Nicolai called me while I was standing with a book in my hand, but the librarian’s stern shushing solved my dilemma as to whether I should answer.

When Nelly texted me that they were heading back from Beersheba, I quickly took myself to the café, ordered two cappuccinos, and even drank one so I could tell her they didn’t know how to make a proper coffee.

“How was it?” Nelly asked when I got into the car.

“Life altering,” I replied, and Nelly laughed. So did Shira. We both swerved our heads toward the back seat.

“See? See?” I told Nelly, who covered her mouth in shock.

“Dad’s funny, right?” she said, just to make the girl talk.

“The funniest,” Shira said and smiled. Nelly and I looked at each other as if our daughter had just uttered her first word.

“We have to get this on tape,” Nelly said and took her phone out of her bag, but her hands were trembling so badly she couldn’t unlock the screen. The girl leaned forward into the radio that was playing “Dreamer” by theAngelcy and looked at it intently, as if the song itself was appearing right before her eyes, a defined shape and volume in space.

“I can’t take it anymore,” she said and leaned her head back. She closed her eyes, the gap between her words and her indifferent gaze unbridgeable.

“Can’t take what?” I asked, but the girl was gone. We sat there in silence, the three of us, until Nelly released the handbrake and started driving.

I couldn’t fall asleep that night. That sentence, “I can’t take it anymore,” kept haunting me. It drove me crazy thinking that maybe there were moments in which Shira was aware of her condition. That her consciousness was trapped in a locked-up body. My mind started racing with all the illnesses I had read about in the library. Meningitis and all kinds of tumors and ALS and epilepsy. I counted them one by one like sheep, and at some point I leaped out of bed in a panic and ran to her room. The dream catcher was hung over her bed and her closet was open. The light from the kitchen illuminated her face with a dull yellow glow. Only after watching her chest rise and fall for an entire minute did I allow myself to calm down. I was thinking of stroking her hair and tried to pinpoint when exactly this had happened—when touch stopped being an instinctive action and became one that demanded an explanation and rationale. And before I could find a reason, I saw it before me. I kept studying her from every angle to make sure I didn’t get it wrong, and realized Nelly had been right from the very beginning. The clue was there, in her eyes.

A sketch from one of the dozens of library books popped into my head. An illustration that demonstrated how pupils move during a dream, from side to side, back and forth. But beneath her thin eyelids I saw Shira’s pupils move differently. In circles, and fast. Too fast.

7.

SHIRA LAY IN bed at the sleep lab, hooked up to all kinds of electrodes and wires.

“You look like a captive alien,” I said. Shira didn’t laugh. I covered her with the blanket up to her waist because I couldn’t tell whether she was actually cold. She fell asleep after a few moments. When she was seven years old, there was a period in which she struggled with sleep but felt bad waking us up, so we didn’t know about it until one day Nelly woke up in the middle of the night and found her sitting in the living room staring at the ceiling. It turned out it had been going on for five days. Ever since, every night at bedtime, Nelly would sit on Shira’s bed and try to get her to confess, as if Nelly was some Irish priest. She wouldn’t let go until Shira spilled her heart out, telling her about the teacher who had yelled at her at school and the boy who whispered to her in the hallway that he loved her. Nelly said she had to know everything. It drove her crazy thinking there might be thoughts buzzing through her daughter’s mind that she wasn’t privy to. I looked at Shira again and wondered whether her silence was a conscious choice. Maybe she knew exactly what was troubling her, but didn’t want to burden us.

I went out into the hallway and sat in one of the chairs. I decided to wait out the night there in the unlikely event that Shira woke up looking for me. An older woman with short red hair sat in front of me, and an agitated old man stood not far from us yelling at one of the technicians.

“Why isn’t anyone getting her a pillow? I don’t get it,” he grumbled. “I just don’t get it!”

The technician tried to calm him down, asking what his wife’s name was. “Lilian, her name is Lilian,” he said and in a huff took to the chair to my left, noticing I was staring at him.

“What are you looking at, huh?”

“Nothing, nothing,” I said, and quickly closed my eyes in a conciliatory gesture. I don’t know if I’d slightly nodded off before I heard the doctor rushing into the technician’s room. The old man, the woman with the red hair, and I all stretched out simultaneously.

“Looks like something serious happened,” the woman said.

I got up and stood by the door.

“Can you hear anything?” the old man asked.

I said I couldn’t.

A few moments later, the door opened and the doctor darted out into the hallway. He tried sidestepping me without making eye contact, but I leaned slightly to the left, bumping into his shoulder. He looked at me and apologized.

“Is there a problem with one of the patients?” I asked.

He glanced at the two others waiting in the hallway, then looked back at me.

“Are you Shira’s father?” he asked.

“Yes,” I replied, and felt in the back of my neck two twinges of relief.

“I can’t say anything for sure yet. We’ve discovered a few abnormal findings, but we have to run more tests,” he said, and apologized for having to rush off. If Nelly knew I didn’t try to stop him, she would have divorced me then and there.

Shira spent the three following nights at the sleep lab. Not that she even noticed. With every night the number of doctors pacing the hallways grew. They didn’t try to hide the fact that it had to do with Shira. Unlike with other patients, who got their wake-up call at 6:00 A.M. and were promptly discharged, a doctor came to examine Shira every morning for a whole hour. All the technicians and doctors I tried talking to said more tests had to be run before they could say anything with any certainty, but sometimes they were willing to drop a few hints. Her REM was three times the normal average. Her brain wave activity was abnormal and her breathing erratic. A collection of symptoms that refused to form a definitive diagnosis. On the fourth night, Nelly insisted on coming. She showed up without notice at midnight with a box of cookies and a small pillow, resting her head on my shoulder and commenting that we were already used to sleeping together in uncomfortable places. She set her alarm clock for seven, but one of the technicians woke us up half an hour before it was to go off, asking that we go see the director of the institute for an update on the situation.

I instantly shot up. Nelly remained seated. “Maybe it’s better not knowing,” she said. I was afraid she was right. We walked into the director’s office and sat down. Nelly yawned and stretched her arms while I scanned the room, as if the answer to what had befallen Shira was somewhere within those four walls. A few diplomas boasting Dr. Mendelson’s name were hung on the wall behind the desk. The desk itself was rather bare, with nothing on it but a large keyboard, green reading lamp, and a wooden-framed photo of what seemed to be her two blond children. They were wearing buttoned-up shirts and jeans, smiling against the white background of the photography studio.

“Straight out of a Gap catalog,” I whispered to Nelly, who then glanced at the photo.

She snorted. “More like a propaganda poster for the Aryan race. Who shot that photo, Goebbels?” she asked just as the director of the institute walked into the room. I covered my mouth, trying not to laugh, doing my best to look like a concerned parent.

The director sat down in front of us, lowering a few thick black notebooks onto the desk. Then she placed her elbows on the desk and crossed her arms, looking at us with a solemn expression and asking how we were holding up.

“Not too great,” Nelly said. She gave me a side-glance, saw that I was still trying to suppress my laughter. Dr. Mendelson’s German looks didn’t help.

“What can I say, Doctor. It’s been …,” Nelly said with a thin smile only I could see, “a real holocaust.”

I cracked up. No matter how hard I tried to get my act together, I just couldn’t stop laughing. Which made Nelly laugh, even louder than me. She didn’t even try to fight it. I saw the doctor’s stern gaze, all the thoughts running through her head about the two wacko parents sitting in front of her. Maybe she got it right, but at that moment, it didn’t matter. Dr. Mendelson nudged the stack of notebooks in our direction and opened the top one.

“What’s that?” I stuttered between fits of laughter, trying to settle my breathing without much success.

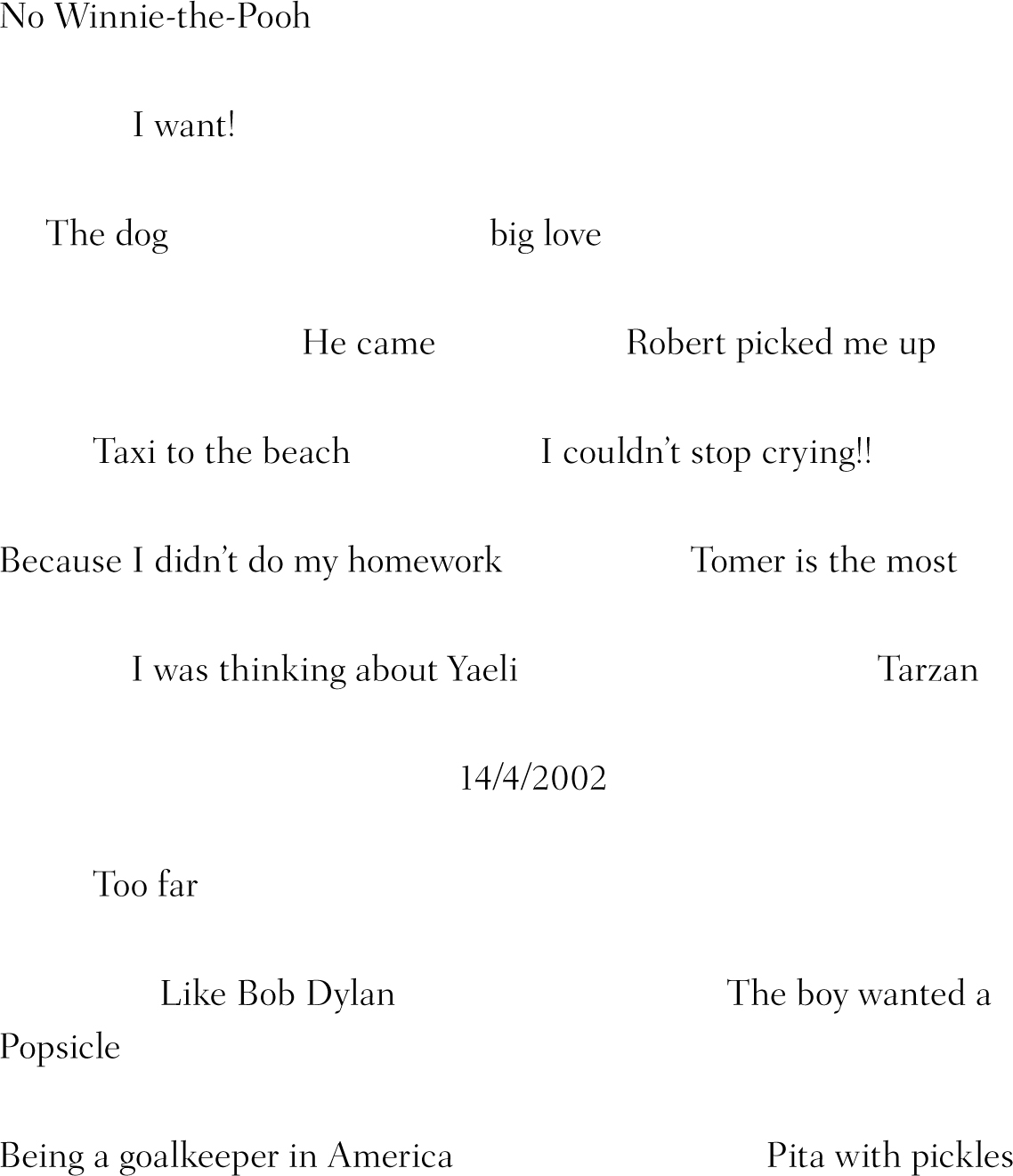

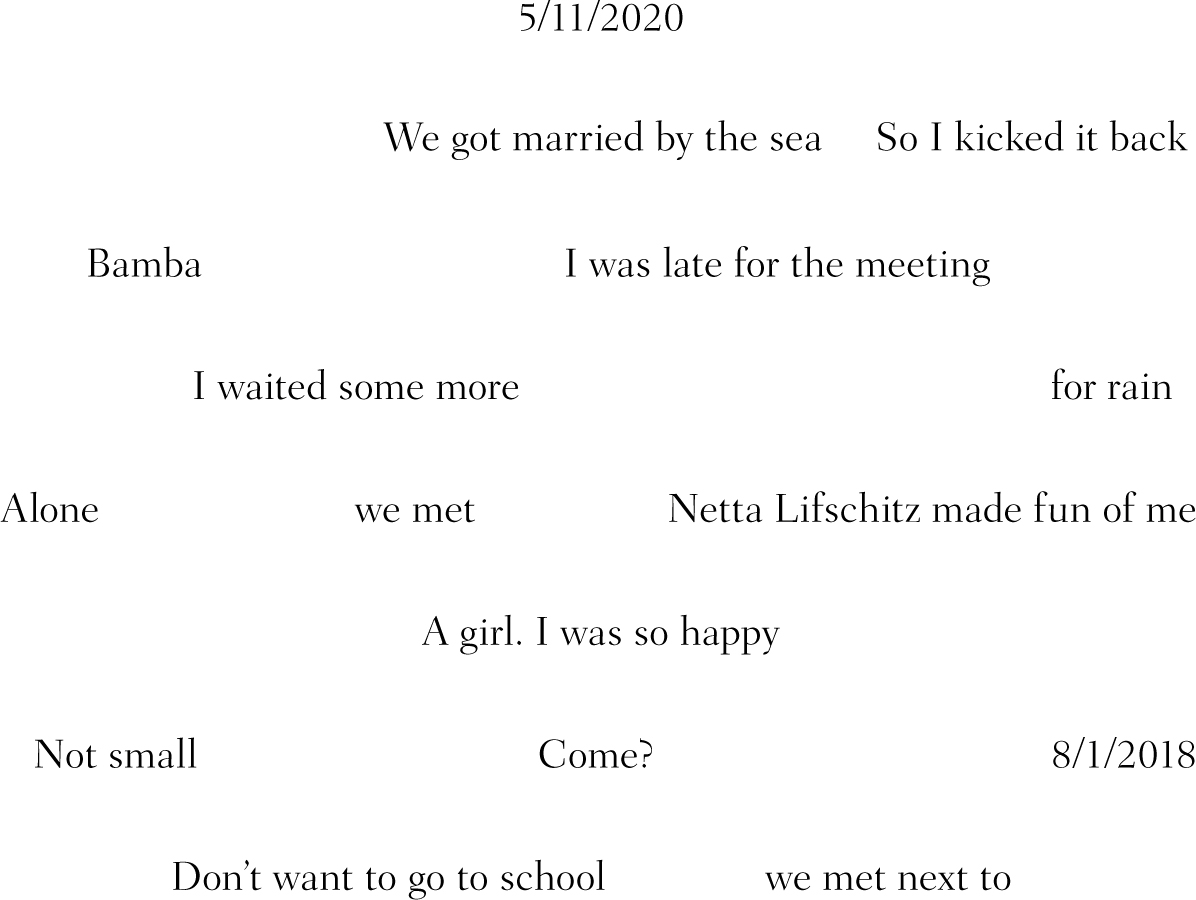

“Shira’s dreams,” she announced. “We asked her every morning to write down what she could remember from her dreams.”

We stopped laughing. We peeked at the pages. There were thousands of misshapen, illegible words, like the doodling of a little girl. “As you know more than anyone, Shira’s fine motor skills have suffered a serious deterioration, which is why her handwriting is basically indecipherable,” Dr. Mendelson said. She told us one of the technicians tried letting her type her dreams onto a computer, but the result was a nonsensical sequence of letters. She took out a yellow marker from the front pocket of her lab coat. “In the notebook, however, we did find a few words we could make out. Mostly single words, here and there a few short sentences. I’d appreciate it if you could go over it. Maybe there are things you could identify better than us.”

We were silent. Dr. Mendelson said she’d give us some time alone and left the room. We stared at the jumbled words in fearful awe. Nelly reached out to the open notebook and pulled it closer to us, then started leafing through the pages slowly. At first she didn’t dare look, and once she did, she couldn’t understand. The handwriting was crabbed and minuscule, a mishmash of letters bumping into each other as if Shira had wanted to make sure no one could read it. I picked up the marker, and we started going over the text, digging for clues. Slowly, very slowly, the words started to surface—mostly unconnected, but sometimes fragmented, illogical sentences.

Who is Netta Lifschitz? Who did she marry? Who’s going to come? A girl? How did she know Bob Dylan? Robert? Who the hell is Robert?

Fragments of Shira flashed before us, and we pored over every word, slowly, sifting through traces of the girl’s consciousness. And every few moments we backtracked, afraid we might have missed a word and disappointed to find out we hadn’t. Her words trampled over each other on the page until they had lost all meaning, contracting and spilling onto the back cover.

“How can someone dream so much, Ofer?” Nelly asked. Like always, she got what this was about before I did. When Dr. Mendelson returned, she started talking about the brain, using all these terms Nelly and I didn’t understand, like sleep cycles and EEG. She explained that when we sleep, we cycle through several stages, one of them being REM sleep—a stage characterized by rapid eye movement, when most dreams occur. She further explained that Shira’s dreams in each cycle were longer than those of other children her age, but it was a negligible difference, a few minutes at most. “It isn’t the actual duration of her dreams, but her subjective experience of that duration. It seems she experiences it as a very long period of time.” The doctor believed that was the root of the problem.

“What do you mean? How long?” Nelly asked her. Dr. Mendelson offered only vague answers, but Nelly wouldn’t let it go. “When we ask most people to write down their dreams, they write anything between half a page and a page and a half,” the doctor said, and then tilted her head toward the notebook. “Shira, on the other hand, wrote eighty pages the first night, and almost a hundred last night.” She said they tried finding a precedent in the professional literature but couldn’t.

“I don’t understand, how long does Shira feel every dream lasts?”

“It really wouldn’t be professional to give you a precise number.”

“Seven? Eight hours?”

“I would estimate more.”

“A day?” Nelly asked, lowering her fist onto the table.

Dr. Mendelson reached for one of the notebooks, picked it up, and gazed at the words. Then she looked up at us. “There are no certainties, we’re still very much in the dark here. But I believe it’s highly probable that Shira feels as though every dream lasts years,” she said, and quickly reiterated that it was merely an initial estimation.

“Days?” I asked, as if I had misheard. Dr. Mendelson turned the notebook in our direction and pointed at a series of numbers that appeared at the top of the page. “I don’t know if you’ve noticed these markings,” she said and began flipping through the pages, showing us that they appeared every few pages.

6/11/2019

7/16/2017

13/8/2020

7/4/2022

27/5/2020

13/9/2018

“We think these are dates.” She said they had never come across a patient who was aware of the dates in her dreams. “The notebooks always begin in 2015, and then leap between dates. In the first notebook, the earliest date was 11/6/2019. In last night’s notebook the date 7/4/2022 appeared.”

Nelly and I looked at each other and couldn’t understand. Didn’t want to understand. Dr. Mendelson explained that the dates never appeared in chronological order. That it was possible every dream was another moment on the time line, and the girl was bouncing back and forth from one dream to another.

“And Shira is the only girl in the world who’s experiencing this?” Nelly asked nervously.

Dr. Mendelson said it was unlikely. That in theory, a lot of people could be experiencing dreams that lasted years, the only difference being that Shira was the only person who remembered them all. “And also the only one whose functioning was severely impaired by this.”

I considered the stack of notebooks again. The words took on new meanings, from a bunch of free associations to possibilities. Every word was a possibility of who Shira could be. The infinity of her private future was laid out on every page, and I was afraid. Afraid that Shira was galloping toward that infinity, getting lost inside it. Dr. Mendelson said they’d carry on with the tests and start her on medication. She promised they’d try everything, and added that there was always the chance that just as her dreams had appeared out of nowhere, they’d eventually disappear. Said there was a lot we didn’t know about the brain, and any attempt to offer an accurate answer as to when and how her condition might change or improve—would be irresponsible.

Nelly reached out and grabbed my hand. She hung her head, mourning our child. Maybe mourning us. Dr. Mendelson said that while she knew it wasn’t much consolation, she had to remind us it could be a lot worse.

“Obviously it’s better than terminal cancer,” Nelly said with frustration and raised her head, squinting as if to hide the redness of her eyes.

“What I meant,” Dr. Mendelson carefully weighed her words, “is that there’s no evidence that the child is suffering.” She said there was almost no indication that she was even having nightmares, and no symptoms of emotional distress. “It may very well be that to a certain extent, she’s happy,” she said, and we remained silent, having forgotten that was even a possibility.

8.

WE RETURNED WITH Shira to the B&B. Nelly’s dad called that evening. Nelly said he hadn’t yelled at her like that in years. He had tried getting an update from Nabil, but the latter hung up on him, thinking it was a prank. “My dad said we had some nerve firing Nabil without even telling him. Got himself all worked up over having to deal with this mess while he was on a cruise.”

Nelly tried telling him it had simply slipped her mind. That with everything that was going on with the girl, her head wasn’t screwed on straight, but her dad replied that with all due respect, that was no reason to go do such a stupid thing. “He said Nabil was coming back to work. And that if we tried pulling another stunt like that we were welcome to rent an apartment in Mitzpe.”

“Did you explain that something felt off? That we felt that—”

“That was just hysterical nonsense,” she said, and lay on the bed. “You know we were dumping all our shit on him.”

I told her she was wrong even though I knew she was right. Then I sat there silently. I got up to brush my teeth, and Nelly gave up. When I came back to bed she was lying with her back to me. I tried thinking about something else. Not about Shira. I broke my rule and read that day’s newspaper, but it didn’t help. Even an article about a space probe landing on Mars made me think about Shira. “It’s crazy,” I said. “Human beings can send a spaceship to Mars but they have no idea what’s going on inside their own brains, it’s just absurd.”

Nelly didn’t respond. I wanted so badly to hear her voice that I decided to keep talking until she said something. “Every dream is a few years for her, can you even imagine that? It’s totally insane. She must be feeling so lonely inside that thing. Really, just thinking about her like that, shifting between dreams with no one beside her, she probably—”

“She’s right,” Nelly said.

“What?” I asked, just to keep her talking.

“Maybe she’s right.”

“Who? Who’s right?”

“The doctor,” Nelly said and turned onto her back. Her eyes were closed.

“Right about what? What are you talking about?”

“That maybe this whole shitty situation,” she said and sighed, “actually isn’t that bad.”

Now I was quiet and Nelly was doing the talking. “It’s not like she’s having nightmares. She’s dreaming. Dreaming all the time,” she said and opened her eyes, looking at me. “I mean really, Ofer, wouldn’t you jump at that opportunity if someone offered it to you?”

“What opportunity? What exactly are you talking about?”

“Think for a second,” she said. “Someone comes and offers you the opportunity to live inside your dreams, without nightmares. To jump from dream to dream every night, to feel as if the whole thing lasts for years. You want to tell me you wouldn’t go for it?”

“Not in a million years,” I replied.

“Really, Ofer? You’d really pass on it? To me it sounds even better than a cruise to the Caribbean,” she said, then hesitated for a moment. “You know what the first thing was that crossed my mind when that Mendelson said the girl wasn’t suffering?”

“What?” I asked.

“That maybe,” she said, and fell silent for a moment. “Maybe Shira chose this.”

“Chose what?” I replied, irritated. “You’re talking in code words, Nelly, I don’t understand.”

“Chose her dreams. Chose to live inside them,” she said and sat up, looking at the door as if she was afraid Shira might be standing on the other side eavesdropping. “I know I sound completely crazy. I know, honestly. But maybe with all those fantasies of hers, she found a way to live inside her dreams. And maybe, just maybe, she’s choosing to live there, make an exit from this world.” She looked at me. “Think, Ofer. Years. Every night is years for her. No wonder she’s barely responsive, doesn’t even recognize us. What’s one day with us compared to years inside her own head?”

“What … what are you talking about?!” I barked at her. “You think she’s choosing to be like this? Completely unresponsive? You actually think anyone would want to live like that?”

I got angry at Nelly. There was no way our child would choose to leave us. “You would think we abused her or something, that she had to escape somewhere.”

“Maybe we didn’t truly see her,” Nelly said, and I knew that when she said “we” she meant “you.” “I don’t know, I’m starting to think we weren’t really there for her. That we were too busy with our own lives. You know what I’m saying?”

“What’s with the guilty conscience bullshit?” I hissed, getting even more annoyed. I told her I hated when she got like that. That once every few months she had those pseudo-pensive moments reflecting on her life and the very next day worked twelve hours straight again. “If tomorrow they call saying they want to appoint you CEO, all these questions would disappear in a flash,” I said, and added, just as a dig, “that’s what separates us from everyone else, remember?”

“What are you talking about?” she asked.

I thought she was being coy, but studying her expression, I realized she wasn’t. She honestly had no idea what I was talking about. I reminded her about that night in the Galilee. What she had said. That drive to push forward.

“You said that’s what separates us from the rest,” I said. “The unapologetic desire to succeed.”

She considered me for a moment with a serious gaze, and slowly her features began to soften. She laughed.

“Sounds like something you heard on a reality show,” she said. “There’s no way I said that.”

I argued with her, reminded her of the details, that the sentence was said after we had gotten out of the Jacuzzi and into bed. She remained unconvinced. She flat out denied it, and I couldn’t understand why. Then she got annoyed with me. “Listen, I don’t remember saying it,” she said, “but even if I did,” she added with a hesitant tone, “it’s just the silly ramblings of a clueless twenty-three-year-old. Nothing more than that. And anyway, the whole CEO business is officially off the table,” she announced. She told me Hakimi had gotten the job two weeks ago. She said it as if it were some inconsequential anecdote, not something she’d been dreaming about for the past seven years. She couldn’t believe she’d been stupid enough to think the move south would give her extra points. Didn’t understand at the time that they were exiling her. I asked her when this had happened, and if she’d spoken with Zuzovsky, but Nelly said she was too tired to talk about it. Which was the last thing I’d expected her to say. I tried coming up with some comforting reply but couldn’t, so I stroked her back gently, tugging her body toward mine. “Enough, don’t turn this into an issue,” she said, but gave in to my touch all the same. “Why didn’t you tell me until now?” I asked, and she said I had enough on my mind and she didn’t want to saddle me with her failures too.

“Maybe you’re right,” she said tiredly, and admitted that maybe she was just upset about not getting the job and that everything she’d said just now about the girl and our lives was a bunch of nonsense. That in a day or two she’d get her act together and find her next goal. “And then I’ll just have the Shira business to deal with,” she added. “No biggie, right?”

I smiled. She placed her head on my knees, and I brushed my hand through her hair. She smiled too.

“I can’t believe how we laughed in her face,” she said. I told her that when Dr. Mendelson opened the notebook, I thought she was going to order us to write “We’re bad parents” forty times or something like that. Nelly laughed again.

“You know,” I said, “I can’t believe that in the twenty-first century they’re still asking people to write down their dreams to understand what’s going on with them.”

“Yup,” Nelly replied. “It’s a shame your guys at Lucid didn’t come up with some technology that would allow people to share their dreams. Because you know, watching someone’s dream is much more interesting than another cooking show on Channel 2.”

“Yup. You’re right. It is more interesting.” I continued to stroke her head. I suddenly had the vague memory of the research department actually exploring that option and ruling it out. How I would have loved to meet her there. Meet Shira in her dreams. One minute there could have solved this whole thing. “It is a shame,” I said.

Nelly turned onto her side, pressed her cheek against my chest, closed her eyes, and fell asleep.

9.

THE FOLLOWING MORNING I saw Nabil wandering outside the B&B, tending to the sheep as if he had never left. Nelly came out and approached him. I stood behind her as she told him she wanted to apologize for everything that had happened, that it was an unfortunate misunderstanding, but the most important thing was that he was back. Nabil didn’t say a word.

“Have a cup of coffee with us?” she asked. He raised his thermos and shook his head. “I really am sorry,” I said. “I should never have fired you.”

“Stop bullshitting me,” he said without looking at me, and went back to work.

Nabil’s words weighed heavily on me, but I was glad he was back. It allowed me to spend more time with Shira. I felt that she needed me more than ever. The notebooks alone took hours out of my day. The doctors made it clear that Shira had to write down her dreams every morning, that it had to be the first order of business. Once I sat her down at the kitchen table, she started writing without my even having to ask. She sat there for two to three hours, until the notebook filled up with words. When she finished writing the last sentence she leaned back, dropped the pencil onto the table, and I put her back to bed, waking her up again in the afternoon.

Shira’s dreams became longer and longer. Every morning the girl wrote more and more words, but the doctors couldn’t explain it. The only thing they cautiously dared to suggest was that the tests indicated the possibility that Shira’s brain could no longer differentiate between wakefulness and sleep. Her sight and hearing were deteriorating sharply, and her sense of smell, taste, and touch was even worse. Her senses were barely functioning, which is exactly what happens to people while dreaming. They explained that might be what was making her so inert.

“That makes no sense,” I protested, telling the doctors it didn’t add up, because there were moments of absolute clarity in which Shira was fully aware of her surroundings. They, on their part, explained that it was like when people experienced a lucid dream—the person knows he’s dreaming. They said it was possible that every now and then Shira’s brain reset itself and understood the difference between a dream and reality, but before she managed to process the situation in full, she would revert back to her hazy existence.

We continued to take Shira to the hospital and the sleep lab, but by that point I had begun to feel that we were doing it more for the doctors than for Shira. They treated her like a math riddle you knew didn’t have an answer but kept trying to solve just for the challenge. I was already exhausted from tending to her 24-7. The revelation regarding Shira’s long dreams should have encouraged us, but in fact did just the opposite. Nelly and I felt as though we had managed to scale the high wall built around the child, only to discover an even higher wall waiting behind it. I tried hinting to Nelly that maybe it was time to start thinking about some kind of treatment facility, just to look into the possibility, but she wouldn’t hear of it. She said there would be nowhere to put her because not a single person in the whole world suffered from the same problem. Said she wouldn’t let her child rot in some loony bin. I started to think maybe she was right. That maybe the girl actually was choosing to remain in her state, and we needed to let go. At least a bit. But I didn’t have the guts to say it out loud, so I kept quiet. I kept quiet and continued to tend to her, but a little less. I gave up on the veggies at breakfast. And on the ten minutes I’d sit beside her after she fell asleep. Sometimes even on the daily stroll to the hilltop, even though I knew she liked it.

Nor was I up to dealing with the app. It wasn’t going anywhere. I couldn’t schedule any meetings in Tel Aviv, and even phone calls with potential business partners couldn’t last more than ten minutes because I had to check on Shira.

I sat in the kitchen every night holding the yellow marker, sifting through the notebooks for clues. At a certain point I stopped trying to decipher the meaning of the words and started to gauge the quantity. I’d sit there with a calculator and try to work out how long every dream lasted. The numbers made no sense. If Shira dreamed every night the duration of approximately three years, that meant that since this all began Shira had dreamed a hundred and twenty years. At least.

One night, Nelly got back from work, approached me from behind, and placed her hand on my shoulder. She looked at the calculator in front of me and said there was no point trying to measure the time inside her dreams. That it was a different kind of time, one which we couldn’t even begin to comprehend.

“What do you mean?” I asked her. She sat down beside me and took the pencil out of my hand.

“I’ve thought about this a lot,” she said, sketching a delicate line on one of the blank pages. She tried to explain that if we likened time to a straight line that moves forward at a steady pace, Shira experienced time as something entirely different. “If anything, I’m starting to think that Shira’s time looks like a bunch of dots,” she said, filling the page with tiny circles. Her theory was that every dream was a dot, and Shira bounced from one dot to the next with no particular order or logic. “One moment she’s at her wedding to that Robert, the next she’s back at Edna’s kindergarten, and then suddenly she’s a goalkeeper in the middle of a soccer game.” She said that explained the fragmented sentences and why the dates were never in chronological order.

“Did you get a master’s in quantum physics and forget to tell me about it?”

“Use that as a pickup line and you can get any woman you want,” she teased and placed her hand on mine.

I looked at the page again, picked up the calculator, and continued to punch in digits. “I’m not sure I agree with you,” I said, and added that even if I did, I wouldn’t quit the calculations. If there was one thing that gave me any kind of comfort in this whole situation with Shira, it was the thought that the girl might live forever in her dreams.

After Shira and Nelly fell asleep, I went out for a stroll by the farm. I walked up to the road and stood on the curb. It was cold. Not a single car drove by. I couldn’t get over what Nelly had said. That the girl consciously chose to live inside her dreams. It made zero sense, but on the other hand, everything that had gone on with Shira in the past month and a half defied the rules of logic. So let’s say, for a moment, that Nelly was right. That Shira actually did find a bug in the system; that she discovered a way to live inside her dreams. Why would she want something like that? That kind of escape? I couldn’t understand it.

There was a time when Shira was little that she liked playing pranks on us. Nelly or I would put her to bed, and she’d pretend to be sleeping, and the moment we walked out of her room she’d burst into laughter. Nelly could play that game with her for maybe an hour, acting as if it was the funniest thing in the world, but I didn’t always have the patience for it. After a few times, I told Shira to quit fooling around. And she really did quit it but only with me, and continued playing with Nelly. After two days I got jealous of Nelly for getting to spend another hour with the girl, who would barely talk to me. During that same period, I’d put her to bed and stand outside her door, waiting to hear her laugh again. But I didn’t hear a thing. It was the first time I realized Shira and I were on different wavelengths. That I simply couldn’t understand her, no matter how hard I tried. Much like today.

My phone rang.

I silenced the ringing but kept staring at the screen. It was Nicolai. For some reason I suddenly thought maybe he could help, and before I even managed to process that thought, I had already picked up.

“Hello? Ofer? Hello?”

“Yup.”

“Wonderful, finally! I been trying to catch you.”

“Yeah, sorry,” I said. “I’ve been a little busy.”

“Never mind, happen to best of us. What important is we’re finally talking,” he said, and embarked on a desperate monologue about all the problems at the office. Said the CEO wouldn’t stop yelling at him. That his best employee had quit yesterday, and that in two weeks’ time his team was supposed to deliver a project and they’d barely gotten half the work done. “Every week someone off sick or take vacation as if we’re not on deadline,” he grumbled. “Just yesterday one took off for Liechtenstein for three days. I didn’t even know that was a country until I look it up on Wikipedia.”

“Neither did I,” I replied, and Nicolai said that it was probably only a matter of time until they fired him. He admitted he hadn’t thought being a development manager was so complicated.

“It is,” I said, hoping my voice didn’t betray my satisfaction.

“But never mind about my problems,” he said with a certain despair. “How are you doing? Already planning retirement?” he asked, and I didn’t know whether it was a bad joke or if he was being serious. I didn’t want to get into it with him, so I just said I was working on a new project.

“Really? What kind?” he asked.

“It’s all very early stages so I can’t really go into detail,” I said. “By the way, Nicolai, if we’re already talking, I wanted to ask something of you. I have a somewhat vague memory of Lucid trying at some point to check the possibility of dealing with the subject of dreams. I’m probably wrong, but is there any chance you could look into it with someone from research?”

Nicolai started laughing even before I was done talking. “Oh, I know what you’re doing!” he said. “Ballsy. For real. Actually sounds like totally cool idea. Little similar, but cool.” Similar to what, I wondered.

“I know there was something, but I can’t really remember,” he said. “I don’t want to give you some off-the-cuff answer, I need looking into it.”

“So there actually was such a project?” I asked, making sure he understood what I was talking about.

“Yes, yes and yes. I think there was even a meeting about it, just few days ago.”

I heard Nicolai taking a deep breath. “Say, Ofer, I also have little favor to ask you. Would you be willing to meet sometime soon, just to shoot the breeze like they say, maybe give some career advice?” he asked with slight trepidation in his voice. “I know it’s probably a lot to ask, but …”

“Yes,” I answered instantly, without thinking. “Sure, no problem. I’d love to.”

He wouldn’t stop thanking me.

I hung up and gazed at the empty road for a few more minutes before heading back home, feeling a flutter of optimism.

10.

“I THINK YOU be happy to hear what I discover,” Nicolai wrote me in a text the next day, and added an emoji of a smiling face with sunglasses.

“What did you discover??” I texted back, adding the second question mark for emphasis.

It was only hours later, after a nerve-racking wait, that he texted back that he’d tell me everything when we meet. From that moment on I couldn’t stop thinking about what they had developed over there. All I remembered was that while working there, the topic of dreams had come up. I just wanted to know if it was possible, if there was a way of getting inside Shira’s head. That maybe, somehow, we could still fix what was wrong with her. I tried imagining what her dreams looked like, but no matter how hard I tried, I simply couldn’t.

That evening, after I tucked Shira into bed, I sat down at the table and went through the notebooks. Nelly had started packing for her conference. She always started getting ready for her trips days in advance, which only stressed her out more. After half an hour she couldn’t take it anymore, grabbed a cigarette and went outside, coming back in two minutes later. She approached the kitchen cabinet and fished out a box of mint tea.

“We’re out of the Mexican brand?” I asked.

“No, I prefer this one.”

“Say,” I asked her while she waited for the water to boil, “if someone told you you could see Shira’s dreams, on TV for instance, would you watch them?”

“Of course,” she said with her back to me.

“Yeah, me too, that’s why lately I’ve been thinking—”

“Actually, maybe not.”

“No?”

“Yeah, on second thought, I wouldn’t want to,” she announced and sat at the table, mixing a teaspoon of sugar into her tea.

“But why?”

She said worst-case scenario she’d watch a nightmare and agonize over how her girl was suffering. “And worse than worst-case scenario, I’d happen to catch a good dream.”