Schedule Important Relationships

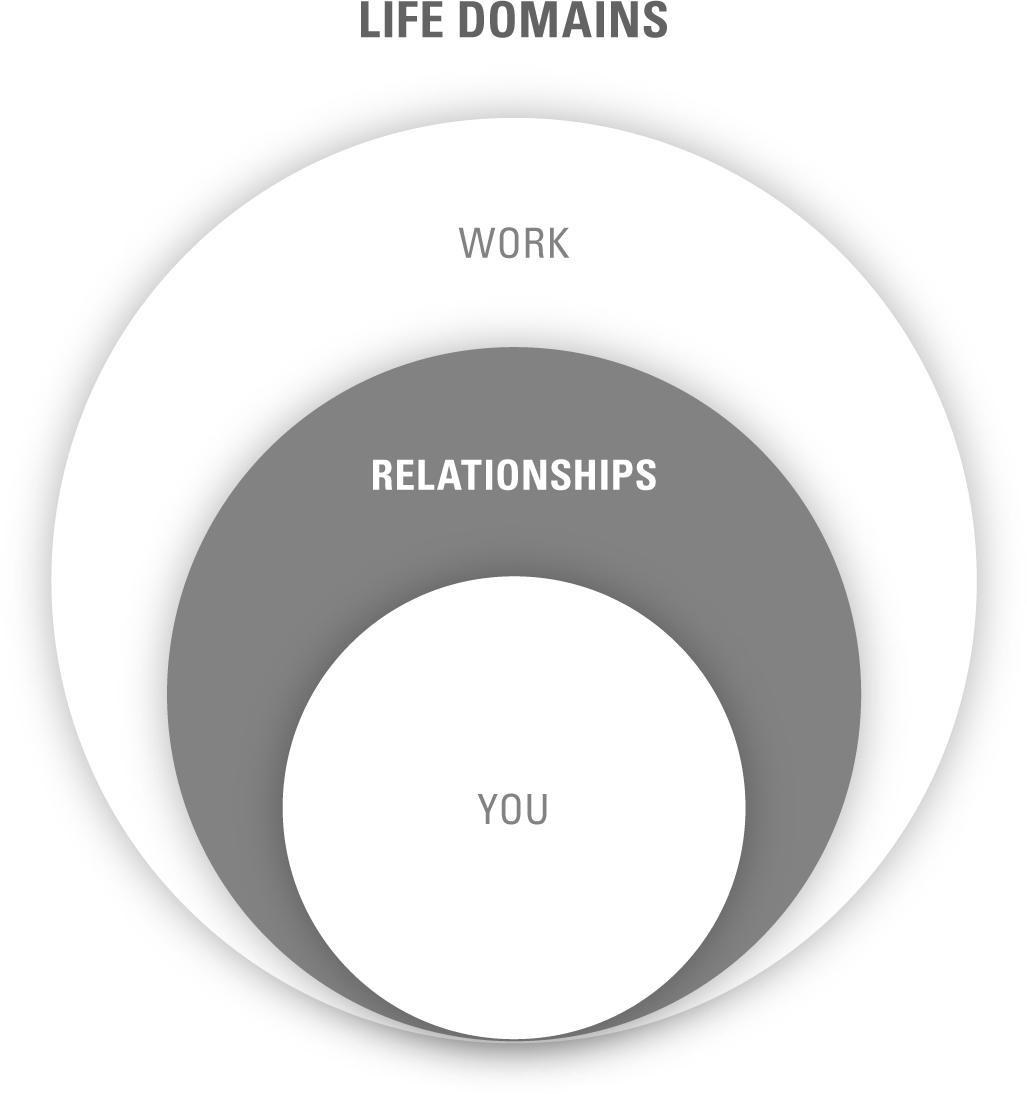

Family and friends help us live our values of connection, loyalty, and responsibility. They need you and you need them, so they are clearly far more important than a mere “residual beneficiary,” a term I first heard in an Economics 101 class. In business, a residual beneficiary is the chump who gets whatever is left over when a company is liquidated—typically, not much. In life, our loved ones deserve better, and yet, if we’re not careful with how we plan our time, residual beneficiaries are exactly what they become.

One of my most important values is to be a caring, involved, and fun dad. While I aspire to live out this value, being a fully present dad is not always “convenient.” An email from a client informs me that my website is down; the plumber texts to tell me that his train is stalled and he needs to reschedule; my bank notifies me of an unexpected charge on my card. Meanwhile, my daughter sits there, waiting for me to play my next card in our game of gin rummy.

To combat this problem, I’ve intentionally scheduled time with my daughter every week. Much like I schedule time for a business meeting or time for myself, I block out time on my schedule to be with her. To make sure we always have something fun to do, we spent one afternoon writing down over a hundred things to do together in town, each one on a separate little strip of paper. Then, we rolled up all the little strips and placed them inside our “fun jar.” Now, every Friday afternoon, we simply pull an activity from the fun jar and do it. Sometimes we’ll visit a museum, while other times we’ll play in the park or visit a highly rated ice cream parlor across town. That time is reserved just for us.

Truth be told, the fun jar idea doesn’t always work as smoothly as I’d like. It’s hard for me to muster up the energy to head to the playground when New York’s temperatures fall below freezing. On those days, a cup of hot cocoa and a couple of chapters of Harry Potter sound way more inviting for us both. What’s important, though, is that I’ve made it a priority in my weekly schedule to live up to my values. Having this time in my schedule allows me to be the dad that I envision myself to be.

Similarly, my wife, Julie, and I make sure we have time scheduled for each other. Twice a month, we plan a special date. Sometimes we see a live show or indulge in an exotic meal. But mostly, we just walk and talk for hours. Regardless of what we do, we know that this time is cemented in our schedules and will not be compromised. In the absence of this scheduled time together, it’s too easy to fill our days with other errands, like running to the grocery store or cleaning the house. My scheduled time with Julie allows me to live out my value of intimacy. There’s no one else I can open up to the way I can with her, but this can only happen if we make the time.

Equality is another value in my marriage. I always thought I behaved in a way that upheld that value. I was wrong. Before my wife and I had a clear schedule in place, we found ourselves bickering about why certain tasks weren’t getting done around the house. Several studies show that among heterosexual couples, husbands don’t do their fair share of the housework, and I was, I’m sad to admit, one of them. Darcy Lockman, a psychologist in New York City, wrote in the Washington Post, “Employed women partnered with employed men carry 65 percent of the family’s child-care responsibilities, a figure that has held steady since the turn of the century.”

But like many men Lockman interviewed in her research, I was somehow oblivious to the tasks my wife handled. As one mother told Lockman,

He’s on his phone or computer while I’m running around like a crazy person getting the kids’ stuff, doing the laundry. He has his coffee in the morning reading his phone while I’m packing lunches, getting our daughter’s clothes out, helping our son with his homework. He just sits there. He doesn’t do it on purpose. He has no awareness of what’s happening around him. I ask him about it and he gets defensive.

It was as if Lockman had interviewed my wife. But if my wife wanted help, why didn’t she just ask? I later came to realize that figuring out how I could be helpful was itself work. Julie couldn’t tell me how I could help because she already had a dozen things on her mind. She wanted me to take initiative, to jump in and start helping out. But I didn’t know how. I had no idea, so I’d either stand there confused or slink off to do something else. Too many evenings followed this script, ending in late dinners, hurt feelings, and sometimes tears.

During one of our date days, we sat down and listed all the household tasks that each of us performed; making sure nothing was left out. Comparing Julie’s (seemingly endless) list to mine was a wake-up call that my value of equality in our marriage needed some help. We agreed to split the household jobs and, most important, timeboxed the tasks on our schedules, leaving no doubt about when they would get done.

Working our way toward a more equitable split of the housework restored integrity to my value of equality in my marriage, which also improved the odds of having a long and happy relationship. Lockman’s research supports this benefit: “A growing body of research in family and clinical studies demonstrates that spousal equality promotes marital success and that inequality undermines it.”

There’s no doubt scheduling time for family and ensuring they were no longer the residual beneficiary of my time greatly improved my relationship with my wife and daughter.

The people we love most should not be content getting whatever time is left over. Everyone benefits when we hold time on our schedule to live up to our values and do our share.

This domain extends beyond just family. Not scheduling time for the important relationships in our lives is more harmful than most people realize. Recent studies have shown that a dearth of social interaction not only leads to loneliness but is also linked to a range of harmful physical effects. In fact, a lack of close friendships may be hazardous to your health.

Perhaps the most compelling evidence that friendships affect longevity comes from the ongoing Harvard Study of Adult Development. Since 1938, researchers have been following the physical health and social habits of 724 men. Robert Waldinger, the study’s current director, said in a TEDx talk, “The clearest message that we get from this seventy-five-year study is this: good relationships keep us happier and healthier. Period.” Socially disconnected people are, according to Waldinger, “less happy; their health declines earlier in midlife; their brain functioning declines sooner; [and] they live shorter lives than people who are not lonely.” Waldinger warned, “It’s not just the number of friends you have . . . It’s the quality of your close relationships that matters.”

What makes for a quality friendship? William Rawlins, a professor of interpersonal communications at Ohio University who studies the way people interact over the course of their lives, told the Atlantic that satisfying friendships need three things: “somebody to talk to, someone to depend on, and someone to enjoy.” Finding someone to talk to, depend on, and enjoy often comes naturally when we’re young, but as we grow into adulthood, the model for how to maintain friendships is less clear. We graduate and go our separate ways, pursuing careers and starting new lives miles apart from our best friends.

Suddenly work obligations and ambitions take priority over having beers with buddies. If children enter the picture, exhilarating nights on the town become exhausted nights on the couch. Unfortunately, the less time we invest in people, the easier it is to make do without them, until one day it is too awkward to reconnect.

This is how friendships die—they starve to death.

But as the research reveals, by allowing our friendships to starve, we’re also malnourishing our own bodies and minds. If the food of friendship is time together, how do we make the time to ensure we’re all fed?

Despite our busy schedules and surfeit of children, my friends and I have developed a social routine that ensures regular get-togethers. We call it the “kibbutz,” which in Hebrew means “gathering.” For our gathering, four couples, my wife and me included, meet every two weeks to talk about one question over a picnic lunch. The question might range from a deep inquiry like, “What is one thing you are thankful your parents taught you?” to a more practical question like, “Should we push our kids to learn things they don’t want, like playing the piano?”

Having a topic helps in two ways: first, it gets us past the small talk of sports and weather, giving us an opportunity to open up about stuff that really matters; second, it prevents the gender split that often happens when couples convene in groups—men in one corner, women in another. Having a question of the day gets us all talking together.

The most important element of the gathering is its consistency; rain or shine, the kibbutz appears on our calendars every other week—same time, same place. There’s no back-and-forth emailing to hammer out logistics. To keep it even simpler, each couple brings their own food so there’s no prep or cleanup. If one couple can’t make it, no big deal; the kibbutz goes ahead as planned.

The gathering lasts about two hours, and I always leave with new ideas and insights. Most important, I feel closer to my friends. Given the importance of close relationships, it’s essential we plan ahead. Knowing there is time set aside for the kibbutz ensures it happens.

No matter what kind of activity fulfills your need for friendship, it’s essential to make time on your calendar for it. The time we spend with our friends isn’t just pleasurable—it’s an investment in our future health and well-being.

![]() REMEMBER THIS

REMEMBER THIS

• The people you love deserve more than getting whatever time is left over. If someone is important to you, make regular time for them on your calendar.

• Go beyond scheduling date days with your significant other. Put domestic chores on your calendar to ensure an equitable split.

• A lack of close friendships may be hazardous to your health. Ensure you maintain important relationships by scheduling time for regular get-togethers.