Jonathan Franzen, the writer Time magazine called the “Great American Novelist,” struggles with distraction just like you and me. The difference, however, between Franzen and most people, is that he takes drastic steps to keep himself focused. According to a 2010 Time profile:

He uses a heavy, obsolete Dell laptop from which he has scoured any trace of hearts and solitaire, down to the level of the operating system. Because Franzen believes you can’t write serious fiction on a computer that’s connected to the internet, he not only removed the Dell’s wireless card but also permanently blocked its Ethernet port. “What you have to do,” he explains, “is you plug in an Ethernet cable with superglue and then you saw off the little head of it.”

Franzen’s methods may seem extreme, but desperate times call for desperate measures. And Franzen is not alone in his methods. Famed director Quentin Tarantino never uses a computer to write his screenplays, preferring to work by hand in a notebook. Pulitzer Prize–winning author Jhumpa Lahiri writes her books with pen and paper and then types them on a computer without internet.

What these creative professionals understand is that focus not only requires keeping distraction out; it also necessitates keeping ourselves in. After we’ve learned to master internal triggers, make time for traction, and hack back external triggers, the last step to becoming indistractable involves preventing ourselves from sliding into distraction. To do so, we must learn a powerful technique called a “precommitment,” which involves removing a future choice in order to overcome our impulsivity.

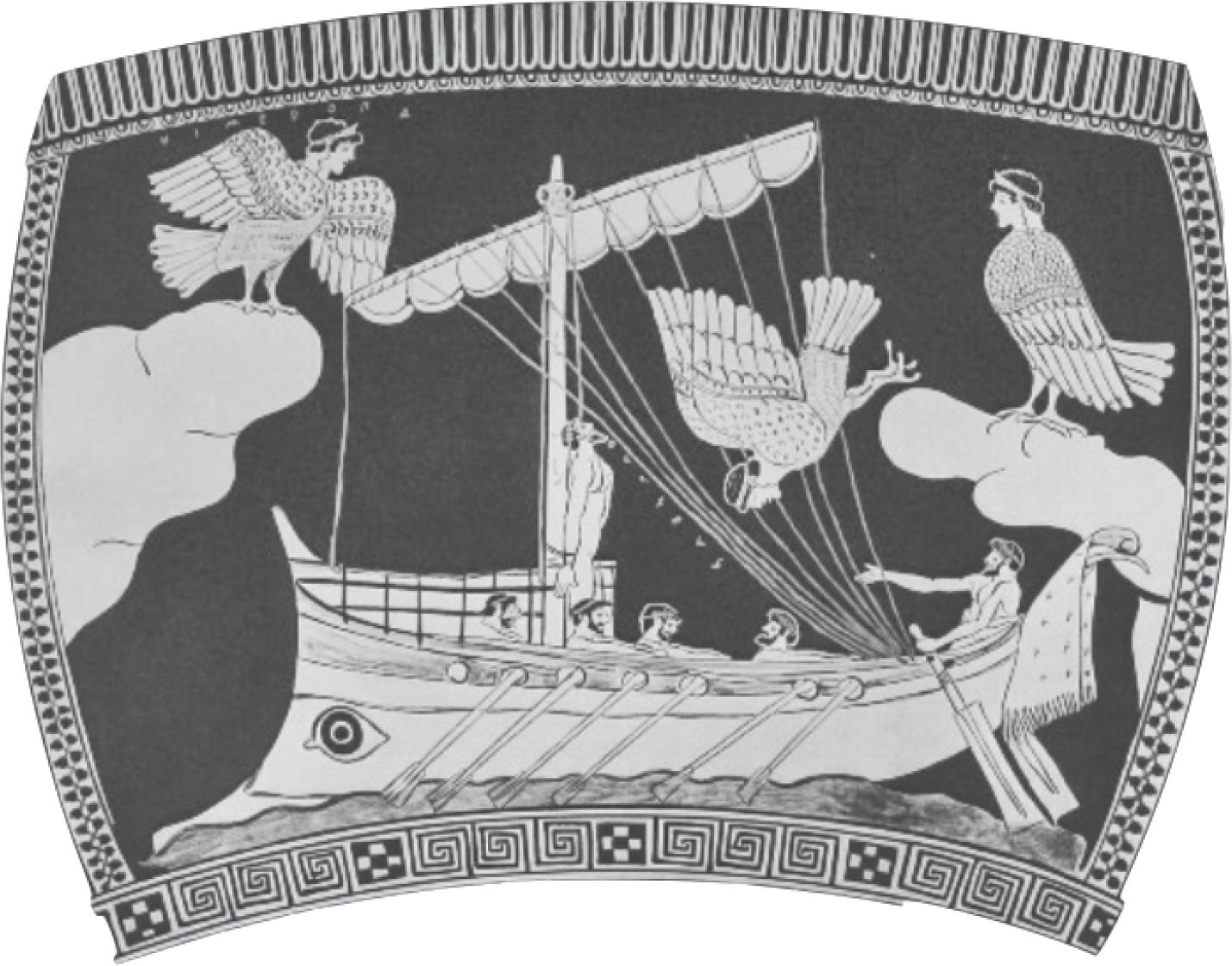

Although researchers are still studying why it is so effective, precommitment is, in fact, an age-old tactic. Perhaps the most iconic precommitment in history appears in the ancient telling of the Odyssey. In the story, Ulysses must sail his ship and crew past the land of the Sirens, who sing a bewitching song known to draw sailors to their shores. When sailors approach, they wreck their ships on the Sirens’ rocky coast and perish.

Knowing the danger ahead, Ulysses hatches a clever plan to avoid this fate. He orders his men to fill their ears with beeswax so they cannot hear the Sirens’ call. Everyone follows Ulysses’s orders, with the exception of Ulysses, who wants to hear the beautiful song for himself.

But Ulysses knows that he will be tempted to either steer his ship toward the rocks or jump into the sea to reach the Sirens. To safeguard himself and his men, he instructs his crew to tie him to the mast of the ship and instructs them not to set him free nor change course until the ship is in the clear, no matter what he says or does. The crew follows Ulysses’s commands, and as the ship passes the Sirens’ shores, he is driven temporarily insane by their song. In an angry rage, he calls for his men to let him go, but since they cannot hear the Sirens nor their captain, they navigate past the danger safely.

In Homer’s Odyssey, Ulysses resists the Sirens’ song by making a precommitment and successfully avoiding the distraction.

A “Ulysses pact” is defined as “a freely made decision that is designed and intended to bind oneself in the future,” and is a type of precommitment we still use today. For example, we precommit to advanced health-care directives to let our doctors and family members know our intentions should we lose our ability to make sound judgments. We precommit to our financial security by depositing money in retirement accounts with steep penalties for early withdrawal to ensure we don’t spend funds we’ll need later in life. We covet the fidelity that is promised in a lifelong relationship bound by the contract of marriage.

Such precommitments are powerful because they cement our intentions when we’re clearheaded and make us less likely to act against our best interests later. Just as we make precommitments in other areas of our lives, we can utilize them in our counteroffensive against distraction.

The most effective time to introduce a precommitment is after we’ve addressed the first three aspects of the Indistractable Model.

If we haven’t fundamentally dealt with the internal triggers driving us toward distraction, as we learned in part one, we’ll be set up for failure. Similarly, if we haven’t set aside time for traction, as we learned in part two, our precommitments will be useless. And finally, if we don’t first remove the external triggers that aren’t serving us before we make a precommitment, it’s likely not going to work. Precommitments are the last line of defense preventing us from sliding into distraction. In the next few chapters we’ll explore the three kinds of precommitments we can use to keep ourselves on track.

![]() REMEMBER THIS

REMEMBER THIS

• Being indistractable does not only require keeping distraction out. It also necessitates reining ourselves in.

• Precommitments can reduce the likelihood of distraction. They help us stick with decisions we’ve made in advance.

• Precommitments should only be used after the other three indistractable strategies have already been applied. Don’t skip the first three steps.