Prevent Distraction with Price Pacts

A price pact is a type of precommitment that involves putting money on the line to encourage us to do what we say we will. Stick to your intended behavior, and you keep the cash; but get distracted, and you forfeit the funds. It sounds harsh, but the results are stunning.

A study published in the New England Journal of Medicine illustrated the power of price pacts by examining three groups of smokers who were trying to quit their unhealthy habit. In the study, a control group was offered educational information and traditional methods, such as free nicotine patches, to encourage smoking cessation. After six months, 6 percent of people in the control group had stopped smoking. The next group, called the “reward group,” was offered $800 if they had stopped smoking after six months—17 percent of them were successful.

However, the third group of participants provided the most interesting results. In this group, called the “deposit group,” participants were required to make a precommitment deposit of $150 of their own money with a pledge to be smoke-free after six months. If, and only if, they reached their goal, they would receive the $150 deposit back. In addition to recouping their cash, successful deposit-group participants would also receive a $650 bonus prize (as opposed to the $800 offered to the “reward” participants) from their employer.

The results? Of those who accepted the deposit challenge, an astounding 52 percent succeeded in meeting their goal! One would imagine that a greater reward ought to lead to greater motivation to succeed, so why would winning the $800 reward be less effective than winning the $650 reward, plus $150 deposit? Perhaps participants in the deposit group were more motivated to quit smoking in the first place? To combat this potential bias, the study’s authors only used data from smokers willing to be in either test group.

Explaining the results, one of the study’s authors wrote that “people are typically more motivated to avoid losses than to seek gains.” Losing hurts more than winning feels good. This irrational tendency, known as “loss aversion,” is a cornerstone of behavioral economics.

I’ve learned how to harness the power of loss aversion in a positive way. A few years ago, I was frustrated at the number of excuses I was making for not exercising regularly. At the time, going to the gym couldn’t have been easier—the fully equipped facility was located in my apartment complex. I couldn’t blame my no-shows on traffic, nor could I blame it on membership dues, because membership was free for residents. Even taking a long walk would be better than doing nothing. Yet I somehow found reasons to skip my workouts.

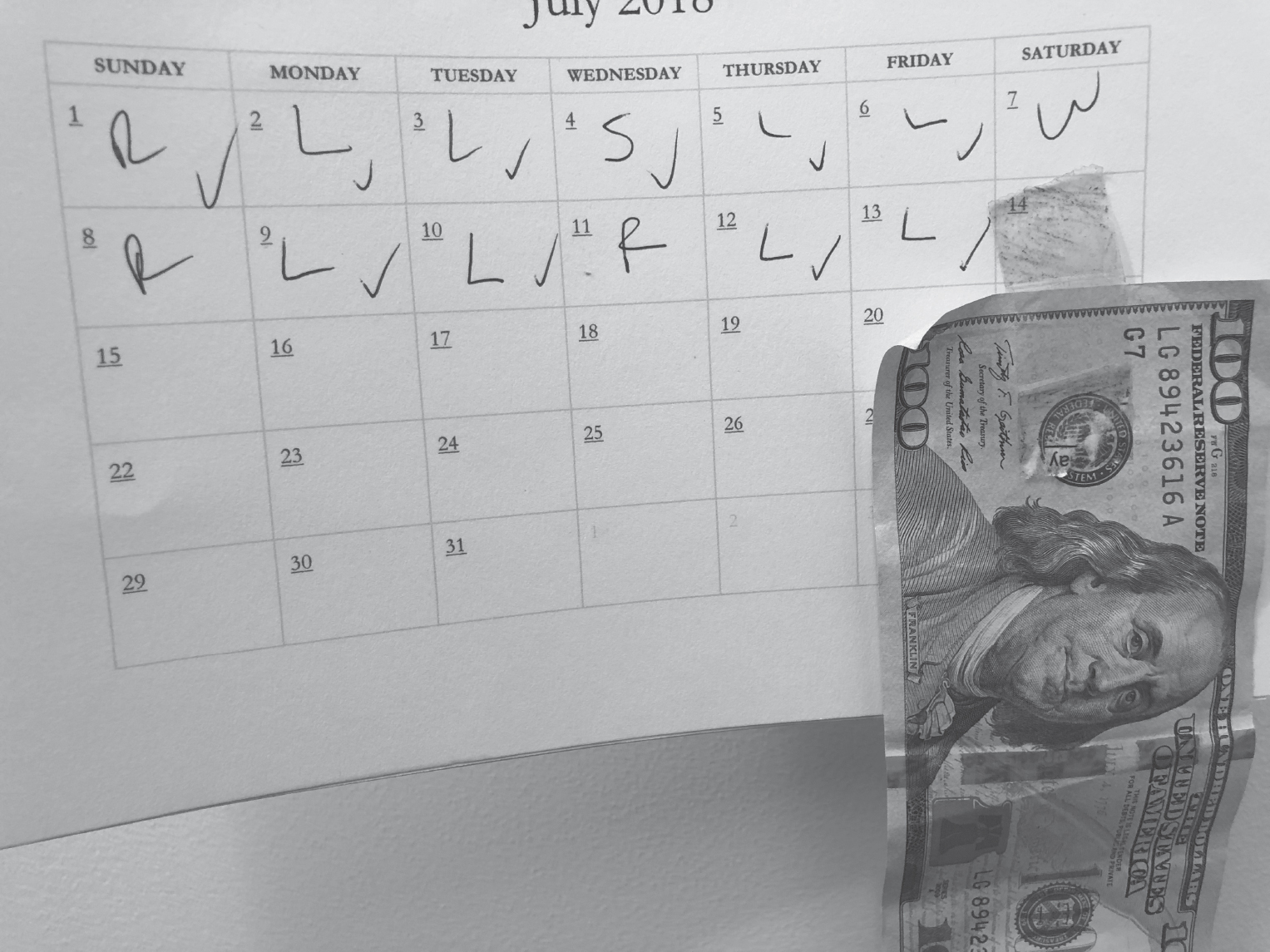

I decided to make a price pact with myself. After making time in my timeboxed schedule, I taped a crisp hundred-dollar bill to the calendar on my wall, next to the date of my upcoming workout. Then I bought a ninety-nine-cent lighter and placed it nearby. Every day, I had a choice to make: I would either burn the calories by exercising or burn the hundred-dollar bill. Unless I was certifiably sick, those were the only two options I allowed myself.

Any time I found myself coming up with petty excuses, I had a crystal clear external trigger that reminded me of the precommitment I made to myself and to my health. I know what you’re thinking: “That’s too extreme! You can’t burn money like that!” That’s exactly my point. I’ve used this “burn or burn” technique for over three years and have gained twelve pounds of muscle, without ever burning the hundred dollars.

My “burn or burn” calendar is one of the first things I see in the morning. It reminds me that I need to either burn calories or burn the hundred-dollar bill.6

As exemplified by my “burn or burn” method, a price pact binds us to action by attaching a price to distraction. But a price pact need not be limited to smoking cessation, weight loss, or fitness goals; in fact, I found it helpful for achieving my professional ambitions as well. After spending nearly five years conducting the research for this book, I knew it was finally time to start putting words on the page, but I found it difficult to get down to writing each day and instead found myself doing even more research, both online and offline. Even worse, I found myself a few clicks away from consuming media that was entirely irrelevant to my writing goals. Clearly, I was not making traction.

Eventually, I’d had enough of my false starts, half-finished chapters, and incomplete outlines. I decided to put some skin in the game and enter a price pact to hold myself accountable to my important goal of finishing this book.

I asked my friend Mark to be my accountability partner in my price pact; if I didn’t finish a first draft of this book by a set date, I had to pay him $10,000. The thought of it made me sick to my stomach—if I forfeited the money, gone would be the vacation budget I’d set aside for my fortieth birthday; gone would be my self-indulgent fund reserved for my new adjustable desk; most devastatingly, gone would be the completion of this book, a goal I so desperately wanted to achieve.

A price pact is effective because it moves the pain of losing to the present moment, as opposed to a far-off future. There’s also nothing special about the dollar amount so long as the sum hurts to lose. For me, the price pact worked like a charm, because knowing that I had so much on the line kicked me into high gear. I committed to a minimum of two hours of distraction-free writing time six days per week, added it to my timeboxed schedule, and got down to work each day. In the end, I was able to keep my money (and my vacation and adjustable desk), and you’re now reading the result of my work.

By this point, you may think price pacts are an impenetrable defense against distraction. Why not just make the cost of distraction so high that you always stay on track? The fact is, price pacts aren’t for everyone and for every situation. While price pacts can be highly effective, they come with some caveats. To experience the best results with price pacts, we need to be aware of and plan for their pitfalls:

PITFALL 1: PRICE PACTS AREN’T GOOD AT CHANGING BEHAVIORS WITH EXTERNAL TRIGGERS YOU CAN’T ESCAPE

There are certain behaviors that aren’t suitable for changing through a price pact. This kind of precommitment is not recommended when you can’t remove the external trigger associated with the behavior.

For example, nail biting is a devilishly hard habit to break because biters are constantly tempted whenever they become aware of their hands. Such body-focused repetitive behaviors are not good candidates for price pacts. Similarly, attempting to finish a big project that requires intense focus while working next to a colleague who wants to continuously show you the latest photos of their “super-cute” puppy is unreasonable. Price pacts only work when you can tune out or turn off the external triggers.

PITFALL 2: PRICE PACTS SHOULD ONLY BE USED FOR SHORT TASKS

Implementing price pacts like my “burn or burn” technique work well because they require short bursts of motivation—a quick trip to the gym, two hours of focused writing time, or “surfing the urge” of a cigarette craving, for example. If we are bound by a pact for too long, we begin to associate it with punishment, which can spawn counterproductive effects, such as resentment of the task or goal.

PITFALL 3: ENTERING A PRICE PACT IS SCARY

Despite knowing how effective they are, most people cringe at the idea of making a price pact in their own lives—I sure did at first! I struggled with committing to my “burn or burn” regimen because I knew it meant I would have to do the uncomfortable work of hitting the gym. Similarly, shaking Mark’s hand and pledging to finish my manuscript made me sweat. Only later did I realize how illogical it was to resist a goal-setting technique that makes success so much more likely.

Expect some trepidation when entering into a price pact, but do it anyway.

PITFALL 4: PRICE PACTS AREN’T FOR PEOPLE WHO BEAT THEMSELVES UP

Though the study discussed above was one of the most successful smoking cessation studies ever conducted, some 48 percent of the participants in the deposit group did not achieve their goal. Behavior change is hard, and some people will fail. Any program for long-term behavior modification must accommodate those of us who, for one reason or another, don’t stick with it. It’s critical to know how to bounce back from failure—as we learned in chapter eight, responding to setbacks with self-compassion instead of self-criticism is the way to get back on track. While trying a price pact, make sure you are able to be kind to yourself and understand that you can always adjust the program to give it another go.

None of the four pitfalls negate the benefits of making a price pact. Rather, they are preconditions to make sure we use the right tool for the job. When used in the right way, price pacts can be a highly effective way to stay focused on a difficult task by assigning a cost to distraction.

![]() REMEMBER THIS

REMEMBER THIS

• A price pact adds a cost to getting distracted. It has been shown to be a highly effective motivator.

• Price pacts are most effective when you can remove the external triggers that lead to distraction.

• Price pacts work best when the distraction is temporary.

• Price pacts can be difficult to start. We fear making a price pact because we know we’ll have to actually do the thing we’re scared to do.

• Learn self-compassion before making a price pact.

![]()

6 If you’re curious, R stands for “run,” L means “lift” (as in lift weights), S stands for “sprints,” W means “walk,” and the check mark indicates I did my writing for the day.