Distraction Is a Sign of Dysfunction

The modern workplace is a constant source of distraction. We plan to work on a big project that demands our undivided attention, but we are distracted from it by a request from our boss. We book an hour of focused work, only to be pulled into yet another “urgent” meeting. We might make time to be with our family or friends after hours, only to be called into a late-night video conference call.

Though we’ve discussed various tactics in earlier chapters, including timeboxing, schedule syncing, and hacking back external triggers in the workplace, for some of us the problem is bigger than upgrading our skills.

While learning to control distractions on our own is important, what do we do when our jobs repeatedly insist on interrupting our plans? How can we do what is best for our careers, not to mention our companies, when we’re constantly distracted? Is today’s always-on work environment the inescapable new normal or is there a better way?

To many, the adoption of various technologies appears to be the source of the problem. After all, as technologies like email, smartphones, and group chat proliferated through enterprises, employees were expected to use these tools to deliver whatever their managers wanted, whenever they wanted it. However, new research into why we get distracted at work reveals a deeper cause.

As we learned in part one, many distractions originate from a need to escape psychological discomfort. So what is making the modern employee so uncomfortable? There is mounting evidence that some organizations make their employees feel a great deal of pain. In fact, a 2006 meta-analysis by Stephen Stansfeld and Bridget Candy at University College London found that a certain kind of work environment can actually cause clinical depression.

Stansfeld and Candy’s study explored several potential factors they suspected could lead to depression in the workplace, including how well teammates worked together, the level of social support, and job security. While these factors are often the topics of watercooler or coffee-break conversation, each proved to have little correlation with mental health.

They did, however, find two particular conditions that predicted a higher likelihood of developing depression at work. “It doesn’t so much matter what you do, but rather the work environment you do it in,” Stansfeld told me.

The first condition involved what the researchers called high “job strain.” This factor was found in environments where employees were expected to meet high expectations yet lacked the ability to control the outcomes. Stansfeld added that this strain can be felt in white-collar as well as blue-collar jobs, and likened the feeling to working on a factory production line without a way to adjust the production pace, even when things go wrong. Like Lucille Ball working in the chocolate factory in the classic episode of I Love Lucy, office workers can experience job strain from emails or assignments rushing by like unwrapped chocolates zooming along a conveyor belt.

The second factor that correlates with workplace depression is an environment with an “effort-reward imbalance,” in which workers don’t see much return for their hard work, be it through increased pay or recognition. At the heart of both job strain and effort-reward imbalance, according to Stansfeld, is a lack of control.

Depression costs the US economy over $51 billion annually in absenteeism, according to Mental Health America, but that number doesn’t even scratch the surface of the lost potential of millions of Americans who suffer at work without a medical diagnosis. Furthermore, it doesn’t account for the mild depression-like symptoms caused by unhealthy work environments that lead to unwanted consequences, such as distraction. Because we turn to our devices to escape discomfort, we often reach for our tech tools to feel better when we experience a lack of control. Checking email or chiming in on a group-chat thread provides the feeling of being productive, regardless of whether our actions are actually making things better.

Technology is not the root cause of distraction at work. The problem goes much deeper.

Leslie Perlow, a consultant turned professor at Harvard Business School, led an extensive four-year study that she documented in her book Sleeping with Your Smartphone. In the book, she writes of managers at the Boston Consulting Group (BCG), a leading strategy consulting firm, who perpetuated the high expectations and low-control work culture associated with mental illness.

For example, Perlow describes a project led by two partners at the firm with opposing work styles. One of them was an early riser, while the other was a night owl. Like parents embroiled in a nasty divorce, the two were rarely in the same room and would communicate through their team. A consultant on the team recalls,

The more junior partner was continually asking us to expand and add things, so we would end up with forty- to sixty-page slide decks for the weekly meetings. The senior partner would wonder why we were all in the red zone [working more than sixty-five hours per week] . . . One partner was up late and would send us changes at 11 pm, the other was up early sending emails at 6 am . . . We were getting it on both ends.

The anecdote may be unique, but the problems it highlights are not. Employees doing their duty and trying to please their managers often feel unable to change the way things function. As a consultant Perlow interviewed said, “Partners like hearing ‘yes,’ more than they like hearing ‘no,’ and I’m trying to give them what they want.”

If a manager sent an email at an hour traditionally reserved for one’s family or sleep, it would be read and replied to. If a manager wanted a meeting to discuss whatever they felt needed discussing, despite other pressing matters, the team would drop everything and attend the meeting. If a manager felt the team needed to work late (irrespective of employees’ existing personal plans), well, you can guess what happened.

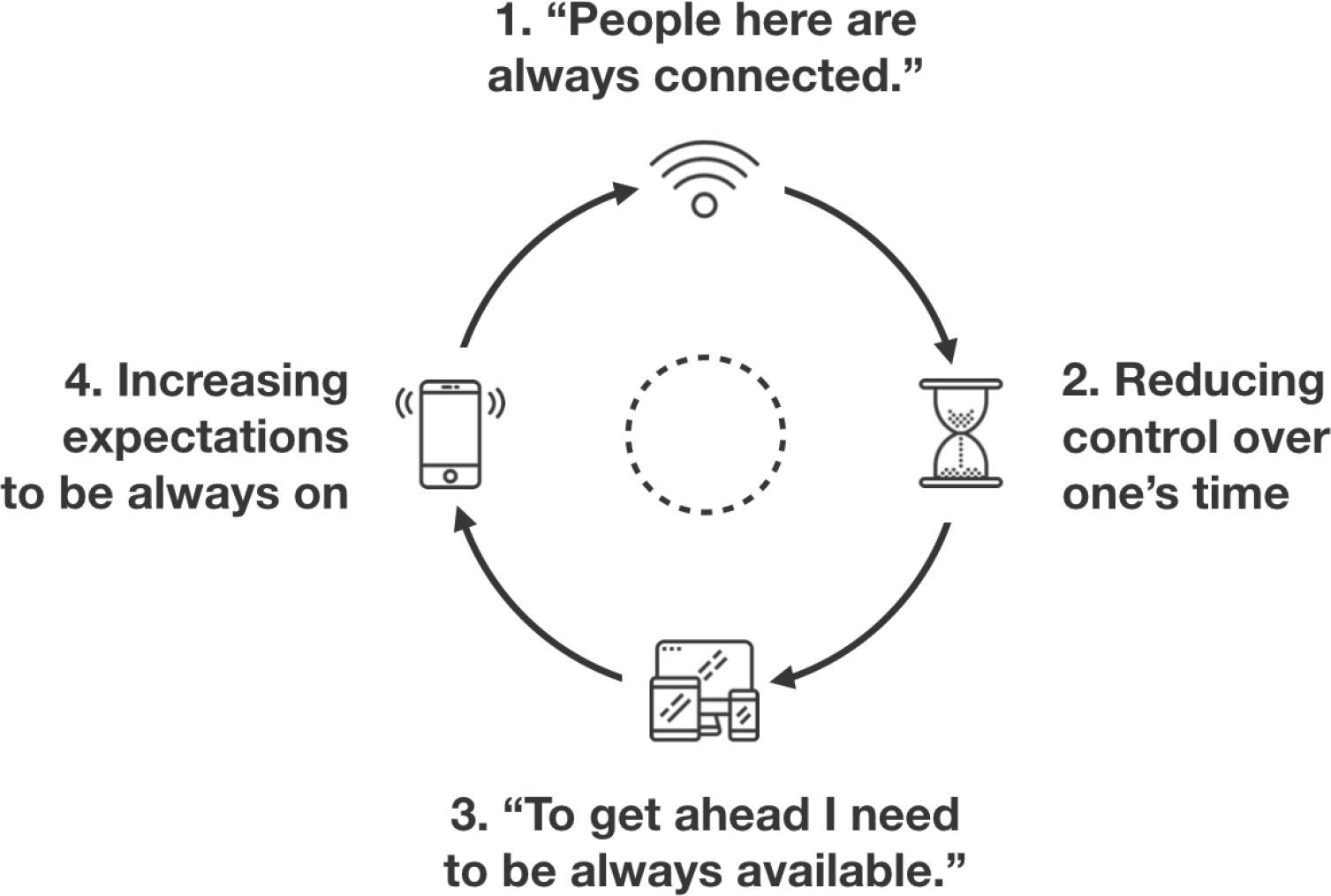

The addition of technology to this corrosive culture made things worse. Perlow describes how the pressure employees feel to be constantly on-call gets amplified in what she calls the “cycle of responsiveness.” She writes, “The pressure to be on usually stems from some seemingly legitimate reason, such as requests from clients or customers or teammates in different time zones.” As a result, employees “begin adjusting to these demands—adapting the technology they use, altering their daily schedules, the way they work, even the way they live their lives and interact with their families and friends—to be better able to meet the increased demands on their time.”

Increased accessibility comes at a high price. Answering emails during your child’s soccer game trains colleagues to expect quick responses during times that were previously off-limits; as a result, requests from the office mutate personal or family time into work time.

More requests mean more pressure to respond, as email inboxes overflow and Slack messages continue to pour in. Soon, a culture of always-on responsiveness becomes the office norm—exactly as it did at BCG.

While technology perpetuates a vicious “cycle of responsiveness,” its cause is a dysfunctional culture. (Source: Inspired by Leslie Perlow book, Sleeping With Your Cell Phone)

The cycle of responsiveness is caused by a cascade of consequences. Technology such as the mobile phone and Slack may perpetuate the cycle, but the technology itself isn’t the source of the problem; rather, overuse is a symptom.

Dysfunctional work culture is the real culprit.

Once Perlow realized the source of the problem, she helped the company change its toxic culture. In the process, she revealed that if a company was unable to address an issue like technology overuse, it was likely also concealing all sorts of deeper problems. In the following chapters in this section, I’ll expand on what Perlow did to help BCG and what you can do to change the culture of distraction at your workplace.

![]() REMEMBER THIS

REMEMBER THIS

• Jobs where employees encounter high expectations and low control have been shown to lead to symptoms of depression.

• Depression-like symptoms are painful. When people feel bad, they use distractions to avoid their pain and regain a sense of control.

• Tech overuse at work is a symptom of a dysfunctional company culture.

• More tech use makes the underlying problems worse, perpetuating a “cycle of responsiveness.”