There’s no way to avoid it: now is the time to talk about stereotypes. And two in particular—namely, the notions that men have better spatial abilities than women and that men are better at parallel parking than women. Let’s unpack these stereotypes and see if it’s phrenology or fact. First, the argument for fact. All sorts of tests show that men consistently score higher than women on tests of spatial ability (one example among many is a much-cited 2003 study in Memory and Cognition by two Canadian researchers, both of whom happen to be female). If you ask whether most men have better spatial visualization skills than most women, the answer, independent of your ideology, opinion, and gender-informed perspective, is yes. Unfortunately, this difference isn’t just an interesting observation—with and without being studied in tandem with gender, spatial ability has been shown to predict high school geometry skills and scores on mathematics sections of college entrance exams. Spatial skills have real-world consequences even beyond scratching the paint on your car’s bumper, and when you line up all men against all women, most men do it slightly better.

The question, then, is why. Is there something innate or genetic in the male brain that makes it better able to imagine the possibilities of shapes? We can certainly see mental rotation tasks in the brain—when researchers from the Montreal Neurological Institute watched people’s brains with fMRI imaging as they matched figures to their rotated forms, blood flow in the brain increased in the right postero-superior parietal cortex, the left inferior parietal cortex, the left inferior parietal region, and the right head of the caudate nucleus. You won’t necessarily be tested on those names, but suffice it to say we know where the brain processes spatial information. And while the results are a bit inconclusive, there’s not really much difference between the brains of men and women as they rotate shapes in their minds. And there’s certainly no male gene linked with spatial ability.

So if gender difference in spatial ability doesn’t necessarily live in the structural capabilities of our brains, where does it live? One answer is that instead of nature, the difference may be due to nurture. Maybe the way men tend to grow up in our culture trains them in spatial abilities in a way that women miss. While many questions involving the brain and culture are met with a fuzzy soup of competing findings, we actually know the answer to this, and it comes from a 1,300-person study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences—in other words, it’s pretty darn solid.

In 2010, researchers from the University of California at San Diego traveled to northeast India to compare people from the Khasi and Karbi tribes. The tribes live next door to each other in the hills surrounding Shillong, and genetic tests show that they are closely related. In the Karbi tribe, women are not supposed to own land and the eldest son inherits property—they are a patrilineal society. In the Khasi tribe, property is inherited by the youngest daughter, men are not allowed to own land, and men are supposed to hand over their earnings to their wife or sister—they are a matrilineal society. This kind of natural division makes researchers drool. And after drooling (or perhaps concurrent with drooling), the researchers had 1,279 people from these villages solve a visual puzzle—anybody who could do it in less than thirty seconds earned a bonus of twenty rupees, about a quarter of a day’s wage.

Here’s what they found: in the patrilineal Karbi tribe, men had better spatial visualization skills, whereas in the matrilineal Khasi tribe, the spatial skills of women were just as good as the skills of men. Furthermore, there were a couple of households in the Karbi tribe that bucked the patrilineal norm. In these few Karbi households in which women happened to own land and money, the gender gap in spatial skills was only a third the size it was in the more common, male-dominated households.

The gender gap in spatial visualization skills is nurture, not necessarily nature. And even in our highly evolved Western society, we remain more Karbi than Khasi. In fact, the gender gap in spatial abilities goes beyond training—there’s an unfortunate difference in how the sexes perform on tests as well. See, on some level many of us are aware of this male-dominated stereotype, and both men and women bring this awareness with them to, for example, college entrance exams. When we bring preconceived notions of skill to a pressure-filled situation, something unfortunate happens; it’s called stereotype threat. Your brain has only so much brainpower to go around, especially in the area of your working memory, which is the part of your consciousness where you manipulate information in a goal-directed way. You need the full power of your working memory to do well on tests, and your working memory famously has limited slots—these are the “chunks,” like digits or other bits of information, that you can keep in the front of your mind at any time. Research shows that worry literally claims space in your working memory, pushing out other useful information or processing ability. This means that the more worried you are that you will do poorly on a test, the more likely you are to do poorly on the test.

Now replace the word worry with the words stereotype threat. In many cases of stereotype, it has been shown that people who fit a negatively stereotyped group worry that they will perform according to the negative stereotype, thus blotting out space in their working memory and helping to ensure that they perform according to the negative stereotype. In this case, women who say to themselves “I’m bad at geometry” are worried when they hit the geometry section of the SAT or ACT, and their worried working memories have less space to find the correct answers.

Does this mean that women are doomed to underperform men in spatial abilities, score lower on math tests, and remain underrepresented in fields such as engineering, science, and technology? Hardly. It’s perfectly possible to blast training and stereotype threat out of the water, for example by doing something as simple as playing a video game for a couple of hours. Researchers from the University of Toronto tested men and women on a spatial visualization test and found that men scored better than women. Then they had both groups play an action video game that required zooming around a three-dimensional space. After ten hours of gaming, the gender difference in spatial visualization skills was eliminated.

Yes, this example is a bit glib—we’re not going to solve the gender gap in STEM fields by playing video games. But it shows that the gender gap in spatial abilities is real and that it can be erased by offering men and women exactly the same training.

Think about this in terms of parallel parking. What training is offered to men and women? To answer this, imagine what happens in most male-female relationships in the United States when both parties get in a car. Do you think that in most relationships the man drives or the woman drives? That’s the training part. And now imagine the testing part—are you aware of the stereotype that men are better at parallel parking than women? If you are, then you help to create a self-fulfilling prophecy. Or you can decide there’s enough repression due to violence inherent in the system, say the heck with parallel parking, and get a car that will do it for you.

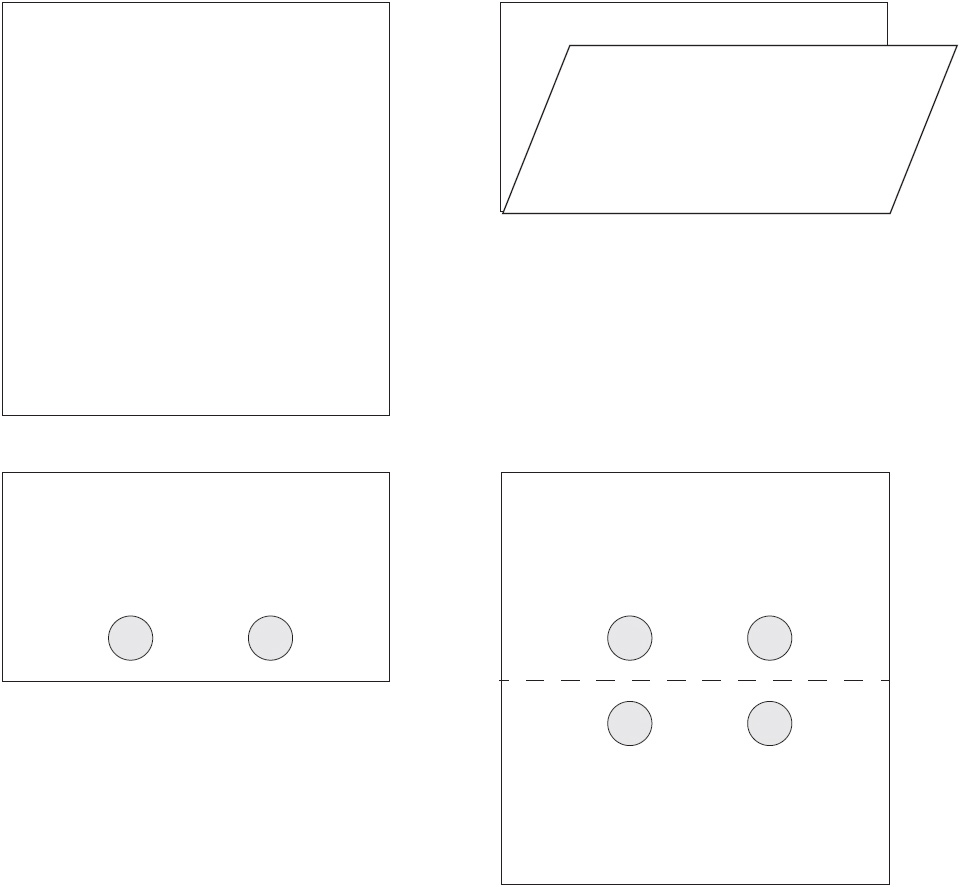

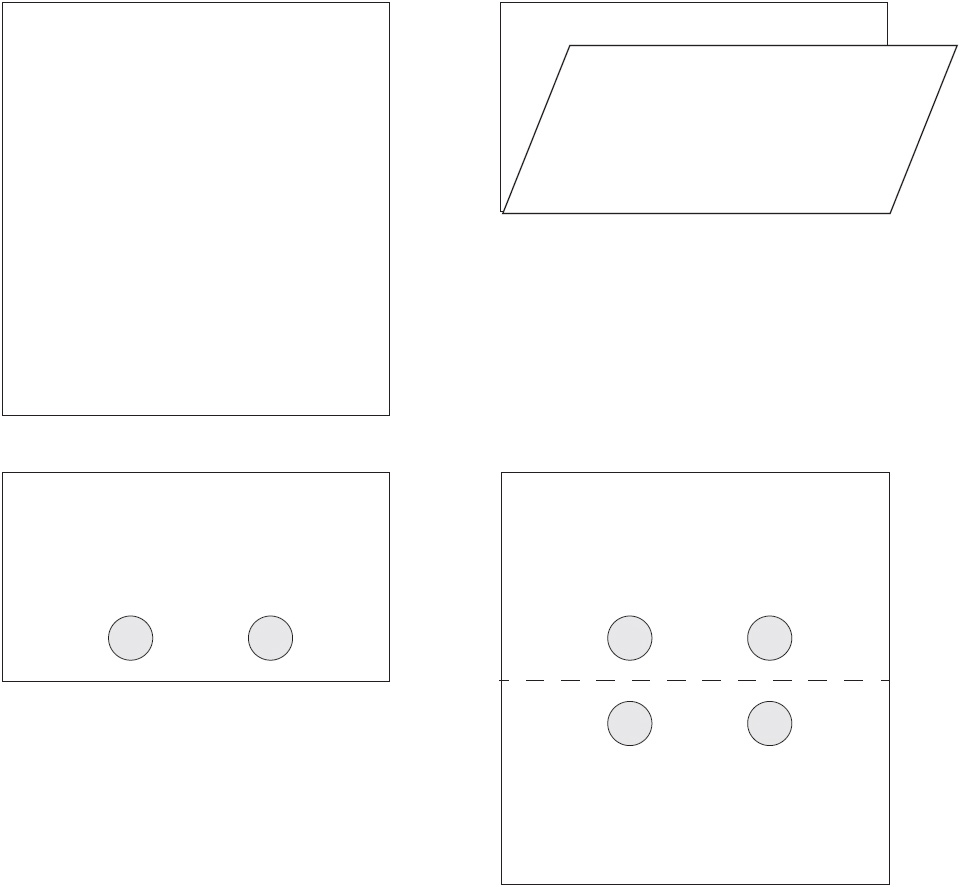

Search online for “paper folding test”—there’s a great version at spatiallearning.org. In this ingenious and devious task, a piece of paper is folded and then a hole is punched in the folded paper. What will the punched paper look like when unfolded? Matching the folds and punch to the correct target forces you to bend your mind’s spatial skills along with the paper. Do it enough and you will improve your spatial abilities. Whether or not this translates to better parallel parking may depend in large part on what you believe. If training your spatial skills makes you feel like a better parallel parker, it can smush the influences of stress and stereotype threat in your brain, making you a better parallel parker.