At the end of March 1811, Napoleon sent instructions that the HQ of the Army of Portugal should remain in Coimbra until it attacked Lisbon! How different was the reality facing the French army. It was a long way from Coimbra and had just left Guarda. Masséna retreated just across the Spanish border, finding himself back where he had started some ten months earlier. His campaign seemed to have been totally fruitless. Many men of the Army of Portugal had been lost at the battle of Bussaco and from exposure in the following months, while unable to pierce the Lines of Torres Vedras, drive the British into the sea and take Lisbon at last. The single, solitary French gain in Portugal had been the fortress of Almeida.

Wellington was not far behind the French. Welcome news was that General Robert Craufurd was arriving from leave in England to resume command of his Light Division. Sir William Erskine had been a relatively competent division commander but, being somewhat unused to the rapid movements of light troops, it had been a difficult duty for him whereas Craufurd was an outstanding light troops general. The news was greeted by all as a good omen for the army as it neared the Spanish border.

Once again, the fortress of Almeida was to play a key role in dictating the course of the campaign. Masséna knew that if he could retain control of Almeida, the Anglo-Portuguese army would be unable to threaten the French hold on western Spain whilst leaving such a powerful enemy base uncaptured in their rear. The French marshal had no intention of keeping his whole army there, as the fortress would probably be surrounded and, in any event, the Spanish plains of Leon would be a better source of food and supplies than the rocky hills of Portugal. The countryside surrounding Almeida, Guarda and Sebugal was devastated and Masséna’s army was critically short of food, forage and all sorts of supplies – a rather sorry-looking shadow of the splendid and confident force that had crossed into Portugal the previous year. He therefore left a strong force in Almeida and his army then fell back towards Ciudad Rodrigo.

Almeida had been partly destroyed by a catastrophic explosion on 26 August 1810 which had led to its surrender to the French and opened the route into Portugal. By drafting labourers the French garrison had, eight months later, made enough repairs to once again make the fortress a mighty obstacle. General Antoine-François Brenier, a tough and experienced veteran, was left as governor of the fortress with a garrison of about 1,300 troops.

Wellington’s troops reached the area in April, and the 6th Division with Pack’s Portuguese Brigade surrounded Almeida. The other divisions and brigades were spread between Almeida and Concepcion. The Light and 5th divisions were at the ruins of Fort Concepcion on the Spanish border acting as the vanguard of Wellington’s army and watching Masséna. Provisions were quite scarce for the Anglo-Portuguese too, and not much could be expected in desolate villages such as Nava de Aver, Pozo Bello or Fuentes de Oñoro, but their commissariat was bringing in enough to sustain the men if not always all the animals. It would have to do for the time being. Wellington had no plans to march into the plains of Leon towards Ciudad Rodrigo. To do so, he believed, would expose his army to a counter-attack by a much stronger French force, as he was convinced that French troops in Spain would reinforce Masséna’s army.

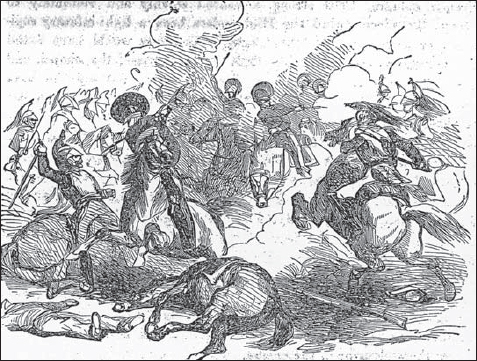

A party of British light dragoons attacks elements of Masséna’s rear guard during the retreat.

Wellington’s hunch proved correct. Marshal Bessières, commander of the 70,000-man French ‘Army of the North’ in Spain was instructed to help his colleague Masséna prevent the British and Portuguese from entering Spain. Bessières was also supposed to be conducting operations against the remnants of the Spanish army in Galicia, however, and was further preoccupied by the intractable guerrilla problem, which required considerable forces to guard strategic points and communication routes. It may well have been Bessières’s intense dislike of Masséna that, in the end, led him to state that all his troops were spoken for and only 1,600 cavalry and a battery of artillery were available.

Wellington, well informed as ever, therefore felt any immediate action by the French was unlikely, given the present state of their armies. He took the opportunity to make a lightning visit to the south. Accompanied by a few staff officers on good horses, he galloped south from Villar Formoso to the fortress of Elvas in five days, arriving there on 20 April, inspected troops and issued orders and then galloped north again, reaching his army at Alameda, a small village between the fortress of Almeida and Ciudad Rodrigo, on the 29th. It was an amazing feat that puzzled French intelligence officers.

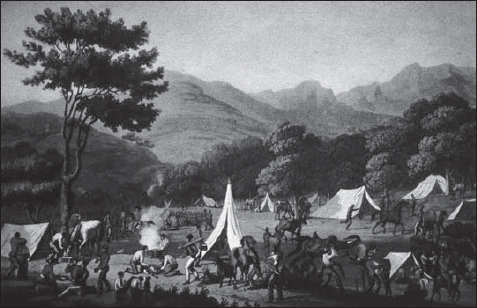

A bivouac of British cavalry near Villa Velha in May 1811. Print after Bradford. (Pedro de Brito Collection, Porto)

Meanwhile, a mortified Napoleon sitting in Paris could only conclude, no doubt with some anguish, that Masséna who had up until then been one of his better marshals, was now a broken man. Following General Foy’s reports he was left in no doubt. There was no alternative, and on 20 April Napoleon signed a letter relieving Masséna of command. Marshal Marmont, who had recently returned to France after a period of command in Dalmatia on the Adriatic, had been ordered to Spain to command 6th Corps following Marshal Ney’s departure. While en route Marmont received the news that Masséna was dismissed and that he would take over command of the entire Army of Portugal rather than just 6th Corps.

Until Marshal Marmont reached the army in western Spain, Masséna remained in command. The French troops, except for the garrison of Almeida, were posted east of the Agueda River and in the area of Ciudad Rodrigo. Although Masséna was not yet aware of his dismissal, he knew he had failed in everything he was supposed to accomplish and that it could not be far off. However, reinforcements, supplies, clothing and ammunition were now reaching him as he could draw on the Army of Portugal reserves still in Spain. Up to 18,000 of these fresh troops were in the Salamanca area and thousands were marched west at once to replace the sick and worn out as well as to reinforce the battalions of the 2nd, 6th and 8th corps. Also in western Spain was General Drouet’s 9th Corps, from which battalions were drawn to reinforce Masséna. Drouet was somewhat reluctant to do this but had no choice in the matter as the commanding officer in the area was Masséna. Thus, in spite of shortages in cavalry horses and in artillery, Masséna was rapidly re-establishing a formidable force, which by 1 May was already 42,000 strong.

Masséna’s main concern was that Almeida should not fall to the Anglo-Portuguese. He had stated that it was a matter of honour that the fortress be held, but the strategic consequences were far more important if Almeida resisted. Masséna aimed to finally defeat Wellington in a general engagement. In this area there were no mountain ranges as at Bussaco and no intricate fortifications such as those north of Lisbon to offer tactical advantages to Wellington and his men. If Masséna won the ensuing battle, and he felt his chances were great on such ground, the victory would vindicate him and, very likely, reinstate him in the emperor’s favour.

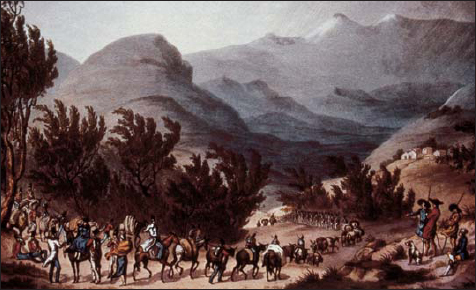

Baggage mules at the rear of the Anglo-Portuguese army on the march in May 1811. Print after Bradford. (Pedro de Brito Collection, Porto)

He faced difficulties, however. His army was far from impressed with its commander-in-chief so far. His tactical imprudence, the amazing resilience of the enemy in Portugal, the shortages of all sorts notably in artillery, his disagreeable manner with other senior officers, his antics with his mistress Henriette Leberton, whom they knew as ‘Madame X’ and the shock of seeing the popular Marshal Ney dismissed, had badly shaken the respect and confidence the army should have had in its leader. Nevertheless, these reasons were not enough to deter French soldiers. Masséna had been a great general and might well regain his laurels if given the chance. A French army, even with low morale, was a fearsome, well-organised and hard-fighting entity whose spirit could quickly change from despair to the sublime if its men saw glimpses of glory – ‘la gloire’ – their ultimate inspiration. Masséna knew all this and knew he had a good chance to turn the tables on Wellington.

On the Allied side, the forces available to Wellington were substantially weaker. Besides the troops blockading Almeida, he had about 37,000 men of whom a little over 10,000 were Portuguese, to face Masséna’s rapidly growing force. The French outnumbered the Allies’ 34,000 infantry by some 8,000 men. The Anglo-Portuguese were especially weak in cavalry with a mere 1,850 troopers, including 312 Portuguese, to face 4,500 French cavalry. Only in artillery did Wellington have superiority over Masséna, with four British and four Portuguese batteries totalling 48 guns against the French 38.

The French might well have had even more troops had it not been for the animosity between marshals Masséna and Bessières. Bessières commanded at Salamanca, and the sudden arrival of Masséna’s 40,000 starving and ragged men from Portugal in his area had greatly strained both the supplies and personal relations already soured by jealousy and power struggles. Bessières sent rations for 20,000 men, which he felt was all he could spare, and further claimed all of his troops were tied up holding down guerrillas. This may have been true, but Masséna doubted it. As Bessières had promised to help Masséna contain the Anglo-Portuguese, he duly marched westward and joined Masséna with a small force consisting of 1,700 cavalry, half of which was detached from the Imperial Guard, and a battery of Imperial Guard horse artillery. Had Bessières been able to gather even 10,000 men, Wellington would have had to withdraw behind the Coa River. Fortunately for the Allied cause, he did not.

The village of Fuentes de Oñoro looking towards the east. The initial French attack on 3 May 1811 came from that direction. (Photo: RC)

Wellington, who enjoyed excellent intelligence largely thanks to the Spanish guerrillas of Don Julian Sanchez, probably knew that he was outnumbered by 2 May, but not by enough enemy troops to warrant a retreat should the French advance to relieve Almeida. Wellington was in a fighting mood if, as ever, prudent.

If one had to pick the quality that most typically characterised Wellington, that quality could well be his remarkable eye for terrain. At first glance, as one nears the Spanish border from the west, the terrain appears to be fairly flat. However, reaching the small village of Fuentes de Oñoro, one notes it is built on a gentle slope just west of the narrow and shallow Dos Casas River. The ground just behind the hamlet is higher and open, stretching across a broad, low plateau until the River Coa is reached about 15 km further west. This meant that a force posted behind the village would have the advantage of higher ground as the flat plain to the east was somewhat lower. The nature of the ground around the village attracted Wellington’s attention, and he saw it as a suitable place to meet a French attack. It was not perfect, as it would be exposed to enemy fire, but it had many sturdy stone walls and solid buildings. The village would also be difficult to outflank. Wellington took advantage of these various features, making Fuentes de Oñoro the southern flank of the Anglo-Portuguese army, guarded by Sir Brent Spencer’s 1st Division.

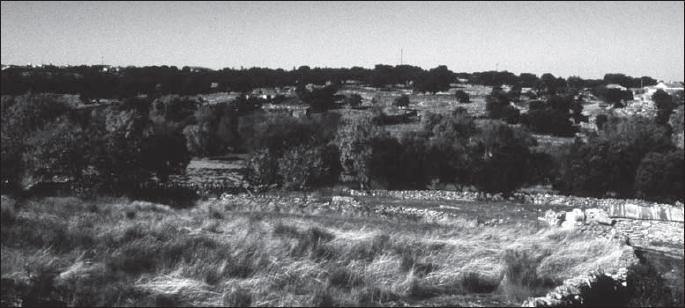

Fuentes de Oñoro as seen from a bluff just southwest of the village. Wellington is likely to have been on that bluff as it offers a commanding view from high ground. (Photo: RC)

To the northwest, in the vicinity of the village of Villar Formoso, were Houston’s 7th Division and Picton’s 3rd Division. Further north was Campbell’s 6th Division on the road midway between the villages of Alameda (not to be confused with the Fortress of Almeida further west) and Sao Pedro. Erskine’s 5th Division was just below Aldea do Obispo near the ruined Fort Concepcion. Just to the north were some Portuguese cavalry piquets. Craufurd’s Light Division with four regi-ments of cavalry was posted further east to keep an eye on the French. Wellington’s army was thus deployed on a north–south line, about 12 km long, between the Dos Casas and Turon rivers. About 10 km west of Fort Concepcion was the fortress of Almeida, held by a French garrison now blockaded by Wellington’s troops.

Fuentes de Oñoro as seen from near the river. This is the view French soldiers would have had as they charged into the village. (Photo:

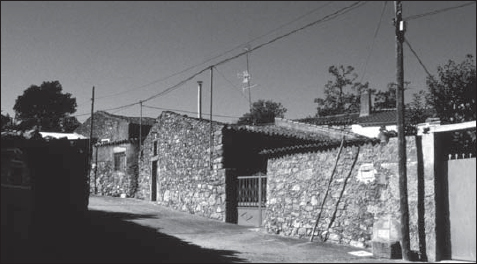

A street in Fuentes de Oñoro that was no doubt the scene of desperate fighting during the bloody battle in 1811. (Photo: RC)

With the Anglo-Portuguese army spread between Aldea del Obispo and Fuentes de Oñoro, Masséna saw an opportunity to strike. On 2 May, he led his army out of Ciudad Rodrigo. The objective was the relief of Almeida and the defeat of Wellington’s army, which stood between him and the fortress. This was a tall order by any standard, but Masséna knew this was his last chance to restore his tarnished reputation by striking a victorious blow. It would instantly vindicate him in the eyes of Napoleon and of his own army. Almeida, the key to Portugal, would be secured and the route opened for another invasion.

A French view of the battle of Fuentes de Oñoro on 5 May 1811 after Martinet. The foreground shows an attack by the French dragoons on infantry in the first phase of the battle. There are of course no mountains in the area such as shown in the background.

The men who marched out of Ciudad Rodrigo were motivated by the prospect of striking at the Anglo-Portuguese and relieving their comrades holding Almeida. After all the humiliations and the retreat from Portugal, the opportunity to attack the hated ‘Anglais’ was welcome. All knew that Masséna had once been a great general and that, with a bit of luck, he could lead them to victory.

The French army marched west on two parallel roads. Predictably, the Allied forward piquets spotted them and there was much skirmishing between the French and Allied scouts. The Light Division gradually fell back before the advancing French troops, who became visible to Wellington’s Allied army as they marched forward during the afternoon. Three columns of troops with about 2–3 km between each could be seen on the plain east of the Dos Casas River. The 2nd Corps formed the northern column marching on the road leading to Aldea do Obispo and ultimately to Fortress Almeida. Next came the centre column made up of the 8th Corps which had only one division marching in the general direction of Sao Pedro. The column to the south was the most powerful with the entire 6th Corps followed by the 9th Corps, which was not yet visible. This column numbering over 30,000 men, was heading straight for the village of Fuentes de Oñoro.

Masséna had concentrated the majority of his forces in a strong southern column, as he suspected that Fuentes de Oñoro was the key to the Anglo-Portuguese position. During the afternoon of 2 May he rode with his staff officers to survey Wellington’s positions. This convinced him that Fuentes de Oñoro was the place to attack. If it fell, not only would part of Wellington’s army be lost, but his line could be rolled up from the south. With luck, the majority of the British and Portuguese soldiers would not escape, the Allied army would be destroyed and Wellington killed or disgraced.

Fuentes de Oñoro, Afternoon, 3 May 1811. Viewed from the south-east showing the initial French attempt to storm the village two days before the main battle.

The fields southwest of Fuentes de Oñoro. This is the area that Masséna hoped his cavalry would sweep across and outflank the Allied army on the morning of 5 May 1811. It proved to be well protected by Wellington’s second defence line. (Photo: RC)

Wellington had just as shrewd a battlefield eye as Masséna, and he also recognised the importance of Fuentes de Oñoro. The Allied troops in Fuentes de Oñoro’s immediate vicinity numbered some 24,000 men, most of them – in typical Wellington style – concealed from the French on the high ground behind the village.

Ferey’s Division from Loison’s 6th Corps was ordered by Masséna to storm Fuentes de Oñoro. It had ten battalions numbering 4,200 men for the task. As a diversion, the northern column (Reynier’s 2nd Corps) was ordered to launch a feint against the British 5th Division at the very northern end of the line. The weak centre column would remain east of San Pedro. All these movements were reported to Wellington by Allied scouts. He naturally suspected that the northern column’s moves towards the 5th Division were merely probes intended to fool him, but he ordered Craufurd’s Light Division to move up closer should the French close in.

In the early afternoon, the six French infantry battalions of the first brigade of Ferey’s Division attacked Fuentes de Oñoro. Waiting for them were 1,800 elite troops under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel W. Williams of the 5/60th consisting of the light companies drawn from 17 British and four Portuguese battalions, two extra light companies from the King’s German Legion, four rifle companies from the 5/60th and one company from the 3/95th Rifles. An additional 460 men belonging to the 2/83rd Foot were also in the village.20

As soon as the French battalions came within range to the east the Allies opened fire, but with little effect, and the French pressed on. The shallow Dos Casas River was practically dry, and they crossed it easily and took possession of some houses on the lower slope next to the river. The Allies counter-charged and the French started to withdraw. General Ferey was on the spot and ordered the five battalions of his second brigade to attack. Desperate fighting ensued in the narrow streets and houses of the village. According to Marbot, the attack of the second brigade might have succeeded but for a case of ‘friendly fire’ in the confusion of battle; in their red tunics the French Hanoverian Legion were mistaken for British infantry and fired upon by the French 66th Line Infantry. Despite the confusion caused by this error, the French slowly forced the British and Portuguese to withdraw through the village. The Allied light companies fought stubbornly into the late afternoon at the foot of the hill behind the village and near Fuentes de Oñoro’s little church.

Field west of Fuentes de Oñoro on a plateau just past the village. This area was where Picton’s 3rd Brigade was posted in reserve, ready to reinforce troops defending the village. (Photo: RC)

Wellington was watching all this from the hill further back. By now the 4,200 French were overwhelming his 2,200 Allied troops and it was time to commit more British troops. The 1/71st, 1/79th and 2/24th were called up from Spencer’s 1st Division. Led by Colonel Henry Cadogan, the three battalions charged into the village and stopped the French. ‘How different the duty of a French officer to ours’, recalled a soldier of the 71st who was there. ‘They stimulating their men by their example, the vociferating, each chaffing each other as they appear in a fury, shouting, to the points of our bayonets’ while ‘after the first huzza the British officers, restraining their men, still as death’ and ‘Steady, lads, steady, is all you hear, and that in an undertone.’ William’s light companies rallied alongside Cadogan’s men and together they counter-attacked the French. More bitter lane-to-lane and house-to-house fighting ensued now as the French in their turn fell back through the village and then across to the east bank of the Dos Casas River. They were followed closely by the British. The men of the 1/71st even crossed the river and advanced up its eastern slope, but they were now too far ahead to be supported and retreated back to the western bank. All the ground gained by the French during the afternoon had been lost.

Marshal Masséna, watching the fighting from a distance, now called up four battalions from Marchand’s division to cover Ferey’s retreating men and allow them to rally. The four French battalions, and other troops that had quickly rallied, secured the ground as far as the east bank of the Dos Casas River. The west bank was held by Wellington’s men and the French did not mount another attack. The shooting died down as night came and both sides remained in their positions.

5 May 1811. Viewed from the south-east showing the first French attacks by Loison’s Corps and Montbrun’s cavalry and the Allied retreat to Wellington’s second defensive line.

The small church of Fuentes de Oñoro as seen from the west. It was the scene of heavy fighting on 5 May 1811. The bayonet charge by the 88th Foot hit the French at this spot. (Photo: RC)

Once again, a French assault against Wellington’s positions had failed with heavy casualties. Ferey’s Division suffered 652 men, killed, wounded or taken prisoner; this figure included three officers and 164 men captured when the troops led by Cadogan had recaptured the village. By comparison, the Allied losses were much lower at 259 killed or wounded including 48 Portuguese.

This initial engagement had showed Masséna that the Allied forces were well dug in at Fuentes de Oñoro. The frontal assault had failed but it remained to be seen if the village could be outflanked. Masséna had previously outflanked Wellington successfully after the battle of Bussaco. Cavalry General Montbrun dispatched reconnaissance parties in every direction to make a thorough survey of the Anglo-Portuguese positions.

From early in the morning of 4 May, parties of French cavalry could be seen riding back and forth at various points north and south of Fuentes de Oñoro. In the village itself, British troops were dug in, taking cover behind stone walls and houses. French troops just across the Dos Casas River had done the same. The enemies were close to each other, separated only by the practically dried-out riverbed, each expecting the other to attack. During the morning, intense firing broke out and continued until sometime before noon, when it finally died away. It seems the French thought the British would try to drive them out of the houses near the river. However, the British had no such plans.

In the afternoon, cavalrymen began returning with their reconnaissance reports. From these, General Montbrun now gained a much better idea of Wellington’s positions, which he reported to Masséna. The Allied army’s positions north of Fuentes de Oñoro were strong and there was no realistic chance of a breakthrough in that area. Reports coming in from the south and southwest revealed that the villages of Pozo Bello and Nava de Aver had nothing but a line of cavalry piquets in front of them and a battalion of infantry in Pozo Bello. From these reports, Masséna determined the next move.

The obvious place to concentrate an attack to outflank the Allied army was to the south of Fuentes de Oñoro. For the attack to succeed the pressure would have to be maintained on the village and points further north so that Wellington could not detach troops to the south to resist the French flanking movement.

Three infantry divisions totalling 17,000 men were assigned to carry out the flanking movement: Marchand’s and Mermet’s divisions from the 6th Corps and Solignac’s from the 8th Corps. The cavalry would consist of Montbrun’s dragoon division and the three brigades under Fournier, Lepic and Wathier for a total of 3,500 troopers. The total attack force, all fresh troops, would thus be 20,500-men strong. These troops would move south of Fuentes de Oñoro and then west at Pozo Bello and its vicinity heading towards Freneda.

To keep the pressure on the rest of Wellington’s line, some 14,000 men in three divisions would attack the village of Fuentes de Oñoro. Further north, Reynier’s Corps would make limited attacks on the Allied line. If it proved weakly defended, a major attack would be launched.

This was a complex but sound plan, certainly better than any of Masséna’s previous battle plans since entering Portugal in 1810. He knew he had a definite numerical advantage over Wellington although probably not the extent of it. Masséna in fact outnumbered Wellington by some 11,000 men. As darkness fell on 4 May, Masséna’s 48,500 men started moving to their appointed position for the attack the next morning.

While Masséna was planning, Allied army scouts were watching every French movement. Wellington considered good intelligence of the utmost importance and his headquarters was alive with cavalry and staff officers riding in and out with the latest information. His Portuguese Corps of Mounted Guides was attached to his immediate staff and included officers and troopers that were familiar with the country and who could generally assess the quality of information from prisoners and deserters. Communication with distant Lisbon could be remarkably swift thanks to the newly created Portuguese army telegraph corps. Now that the Allied army was entering Spain, the guerrillas of Don Julian Sanchez eagerly provided Wellington with intelligence on the movements of the French.

The French had nothing like the intelligence network that had been developed by the British and Portuguese. One of Masséna’s staff officers, Pelet, later wrote that ‘the bands of Spanish insurgents and the English army supported each other. Without the English the Spanish would have been quickly dispersed or crushed. In the absence of the guerrillas, the French armies would have acquired a unity and strength that they were never able to achieve in this country, and the Anglo-Portuguese army, unwarned of our operations and projects, would have been unable to withstand concentrated operations.’

From Wellington’s perspective, the intelligence being received on 4 May spoke of a remarkably quiet French army. As he ‘never slept comfortably’ when opposed by Masséna, Wellington was sure something was afoot. Clearly another attack … but where? His flanks seemed the most likely target. The northern flank seemed secure so it had to be the southern flank, which was indeed where most of the French army was poised. Late in the day, his scouts noticed stirrings in the French camps. They were preparing to move. Wellington ordered his four British regiments of cavalry to string out to the south with mounted guerrillas of Don Julian Sanchez at the far southern end near Nava de Aver. Stretched over 5 km, it was not a strong formation and would not stop an enemy force, but it would provide a first obstacle. The 4,500 men of Houston’s 7th Division were ordered to move south and post themselves behind the village of Pozo Bello, except for the 85th Foot and the 2nd Cazadores stationed in the village itself.

Masséna noted that Wellington’s southern flank was overextended and ordered the bulk of his cavalry to assault the Allied right supported by three infantry divisions. Thousands of French troopers swept through the village of Pozo Bello defended by the British 85th Foot and 2nd Portuguese Cazadores. The defenders were badly mauled in the ensuing melee but, like most of the troops on Wellington’s right, managed to retreat to the strong new defense line established further north. (Patrice Courcelle)

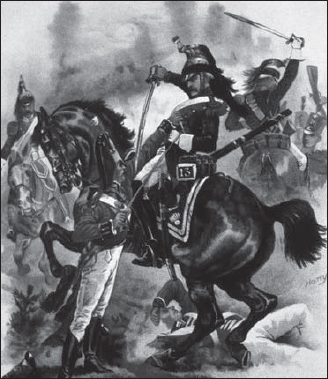

Captain Ramsay and his Royal Horse Artillery gunners galloping through the French in his famous and successful bid to save his two guns at the battle of Fuentes de Oñoro in the morning of 5 May 1811.

The Spanish guerrillas of Don Julian Sanchez had had lookouts at Nava de Aver since 3 May. On the evening of the 4th, they were joined by two squadrons of the 14th Light Dragoons. At daybreak on 5 May Major T.W. Brotherton asked Don Julian to show him where he had posted his forward piquets. Don Julian saw horsemen in the fog to the east and thought they were his lookouts. Brotherton was dubious as it seemed like a lot of horsemen for a piquet. As the fog lifted, Brotherton recalled, they were seen to be ‘a whole French regiment dismounted. They now mounted immediately and advanced against us.’

It was the first wave of Monbrun’s dragoons followed by a mass of troopers who seemed to cover the plain to the east. The Spanish guerrillas were surprised by the French dragoons and galloped off to the west without offering resistance. Hordes of French dragoons now galloped past Nava de Aver. The two squadrons of the British 14th Light Dragoons retreated to the northwest, fighting off the French troopers as they fell back. At this point, the main body of French cavalry encountered the British 16th Light Dragoons and the 1st Hussars of the King’s German Legion, who were posted further north, forming a line between Nava de Aver and Pozo Bello. The 16th and the hussars formed up and, rather amazingly, charged the French cavalry in an attempt to halt them. They lost many men, soon realised they would be overwhelmed and galloped back to Pozo Bello pursued by hordes of French troopers. Brotherton’s two squadrons of the 14th Light Dragoons, who were also retreating from further south, now arrived at Pozo Bello.

By then, masses of French dragoons were closing in on the village of Pozo Bello. It was about 7.00am and, up until now, only French cavalry had been engaged. Infantry arrived on the scene in the form of the two divisions of Generals Marchand and Mermet. Marchand’s Division, some 12 battalions totalling nearly 5,900 men, moved up to Pozo Bello. The French voltigeurs rapidly cleared the woods just east of the village of its Anglo-Portuguese skirmishers and then charged into the hamlet. The 85th Foot and the 2nd Cazadores knew they could not stand for long against such odds and retreated north from the village, but it was already almost too late. As the British and Portuguese soldiers streamed out of Pozo Bello, they were unexpectedly set upon by a large body of French cavalry on their flank. Within a few minutes, the 85th and 2nd Cazadores lost 150 men but the rest of the battalions managed to get away thanks to two squadrons of the King’s German Legion hussars who charged the oncoming French. A few companies of the 95th Rifles also came to the rescue, and Costello recalled seeing that ‘the 85th Regiment, in their conspicuous red dresses, were being very roughly handled by the enemy in this, their first engagement since arriving in the country.’ This assistance allowed the two Allied battalions time to form a new defence line running westward and linking with the 7th Division 2 km away.

Captain Ramsay saving his guns at Fuentes de Oñoro according to a print in Stoqueller’s 1852 biography of Wellington.

Captain Ramsay saving his guns at Fuentes de Oñoro according to a print after Harry Payne.

The 7th Division was rather isolated from the rest of Wellington’s army and there was a real possibility that it might be cut off. The battalions of French infantry coming out of Pozo Bello were formed into columns heading north while Montbrun’s cavalry were in pursuit of the retreating British and Portuguese. Wellington could see all this and realised the danger to the 7th Division. It was equally clear that Masséna and his generals had also seen the weakness of his overextended line to the south. Wellington ordered that a new defence line be established running west from Fuentes de Oñoro for about 3 km with piquets as far as the village of Freneda. The Light Division formed a line from Fuentes de Oñoro with Spencer’s 1st Division west of it. Houston’s somewhat mauled but still formidable 7th Division would retreat to place itself west of the 1st Division. It was a superb and very rapid tactical move on Wellington’s part, testimony to his exceptional ability to react swiftly to unfolding events. This new line was less extended and could still foil the French flanking movement.

5 May 1811. Viewed from the south-east showing the French assault on the village of Fuentes de Oñoro itself.

During the French cavalry attack that overwhelmed a detachment of the Foot Guards, Captain Home of the 3rd Foot Guards (or Scots Guards) was attacked by three French troopers. A man of uncommon muscular strength, Home repulsed all three. The uniform of the French trooper is erroneous. The 13th Chasseur à cheval did not have helmets nor cuirasses as it was a light cavalry unit wearing shakos and green jackets with orange collar and green cuffs. Brown overalls strapped with leather were often worn in Spain and the men of the 13th still wore queues in 1813. (Print after Harry Payne)

Meanwhile, some 2,700 French troopers were sweeping everything before them as they rode north pursuing the 85th Foot and the 2nd Cazadores. To cover the Allied infantrymen and slow down the French, some 1,400 British light cavalry of Slade’s and Arentschild’s brigades and Bull’s Battery of the Royal Horse Artillery stood in the way. Montbrun’s dragoons and generals Wathier’s and Fournier’s brigades of Chasseurs à cheval and hussars clashed with the British 1st Dragoons, the 14th and 16th light dragoons and the King’s German Legion’s 1st Hussars. It could only be a holding action against the greatly superior French attackers and the British troopers fell back, one squadron fighting while the other retreated before it halted and in turn covered the other squadron’s retreat. This fighting lasted for a long time, indicative of the obstinacy of the troopers of both sides. The French believed they had routed the British but, although they lost nearly 160 men, the British troopers remained in formation as they withdrew, eventually falling back past the 7th Division’s infantrymen.

General Houston deployed his 7th Division, which was joined by the 85th Foot and the 2nd Cazadores, at the foot of a gentle slope with some battalions taking cover behind low stone walls. The orderly formation of Montbrun’s cavalry was somewhat disrupted as it came face to face with Houston’s Division. The French troopers menaced Houston’s centre and a French horse artillery battery came up to fire at it while Montbrun sent a brigade of dragoons to outflank the British position on the west side. This seemed to work and they charged towards the British flank when, from behind a stone wall, the Chasseurs Britanniques opened a robust volley fire at close range that checked and unnerved the dragoons; they fell back. A similar attempt on the 51st Foot met with the same fate. Private Wheeler of the 51st recalled the effect of the volleys: ‘For a moment the smoke hindered us from seeing the effect of our fire, but we soon saw plenty of horses and men stretched not so many yards from us.’ The French cavalry retreated to regroup.

Craufurd’s Light Division was now arriving to the rear of Houston’s 7th Division. Houston moved his division further to the northwest to cover a possible flanking manoeuvre. The Light Division with the remnants of the British dragoons and light cavalry now barred the way of the French troopers. The British and Portuguese light infantry was formed into squares with the cavalry and a few field guns in between.

The French infantry and artillery was brought up to attack the Light Division, and soon, some 15 guns were on the field. The British cavalry troopers repeatedly charged the French guns, preventing their effective use against the Allied infantry packed into compact squares. Craufurd was now ordered to retreat and join the 1st Division to complete Wellington’s line. This was achieved with the pursuing French cavalry close behind.

During this retreat occurred a most singular incident when Captain Norman Ramsay’s two guns of Bull’s troop of the Royal Horse Artillery were overtaken and surrounded by the pursuing French cavalry. They had fallen behind as they had repeatedly halted to discharge a shot or two to slow the pursuit. What happened next is best told in the stirring words of William Napier’s history of the war which immortalised this event: … a great commotion was observed amongst the French squadrons; men and officers [of the French cavalry] closed in confusion towards one point where a thick dust was rising, and where loud cries and sparkling of blades and flashing of pistols indicated some extraordinary occurrence. Suddenly the multitude was violently agitated, an English shout arose, the mass was rent assunder, and Norman Ramsay burst forth at the head of his battery [actually two guns], his horses breathing fire and stretching like greyhounds along the plain, his guns bounding like things of no weight; and the mounted gunners in close and compact order protecting the rear.21 As Ramsay’s horse artillerymen were galloping desperately towards the British line, a squadron of the 14th Light Dragoons and a squadron of the 1st Royal Dragoons, seeing the guns in danger, turned back and charged the pursuing French cavalry which allowed Ramsay to reach the 1st Division safely amidst the cheers of its infantrymen, who had witnessed the whole incident.

The French were more fortunate a little further west. There, a piquet from Stopford’s Foot Guards Brigade in Spencer’s 1st Division formed a small square to resist the oncoming French cavalry. The square easily beat off the rather disorganized charge by the French troopers. Unfortunately, their commander, Lieutenant-Colonel George Hill of the Scots Guards, then ordered his men into an extended skirmish line again. At that point came a second charge made by the 13th Chasseurs à cheval that broke through three companies and cut down some 70 men in a matter of minutes, taking Hill and 20 others prisoner. The rest of the guards piquet banded together and resisted the onslaught as best it could until relieved by a troop of the 1st Royal Dragoons and a squadron of the 14th Light Dragoons. By that time, the Guards had suffered about 100 casualties.22

These episodes were only two of several attacks made by the French cavalry on Wellington’s southern flank, but the new Allied position was obviously strong. Montbrun now felt that the already hard-hit 1st Division was ripe for an all-out general charge, which, if carried out by a strong body of attacking cavalry, had a good chance of piercing the Allied line. Behind his dragoons and light cavalrymen was Lepic’s Brigade – a reserve of some 881 officers and troopers of the Imperial Guard cavalry. Added to his men, these elite horsemen would form a force of some 3,500 cavalry to hurl at Spencer’s 1st Division. The French infantry of Loison’s 6th Corps would follow as soon as a breach had been made. Montbrun called on Lepic to bring his Guard cavalry forward, but to Monbrun’s mortification, Lepic answered that he could not as only Marshal Bessières had the power to authorise the deployment of his cavalry. A frantic search began for Bessières, who could have been anywhere on the battlefield. He was eventually found near Pezzo Bello, but by this time Monbrun’s opportunity had passed as the 1st and 7th divisions and the Light Division had consolidated their positions. As Kinkaid of the 95th Rifles put it, the French that did approach ‘did not seem to like our looks, as we [the Light Division] occupied a low ridge of broken rocks, against which even a rat could scarcely have hoped to advance alive.’

The main French attack was a frontal assault on the village of Fuentes de Oñoro, which met determined resistance from the British garrison of 24th Foot, 71st Highland Light Infantry and 79th Highlanders. A second massive assault by 18 companies of elite French grenadiers led to desperate fighting in the village and was only defeated by the timely arrival of the British light infantry companies and the 6th Portuguese Cazadores. The French now threw in two more divisions and the Allies retreated. Wellington then gave permission for Mackinnon’s Brigade of Picton’s 3rd Division to charge. Picton himself ordered ‘this business must be done with cold steel.’ The bayonet charge by the 45th, 74th and 88th, supported by the surviving defenders, eventually drove the French out after a desperate struggle amid streets choked with dead and wounded. (Patrice Courcelle)

French accounts largely blame this blunder for the failure of their army at Fuentes de Oñoro. However, as British and Portuguese historians point out, it was far from certain that the French cavalry – Imperial Guard or not – would have broken through the British and Portuguese regiments. The 3,500 French troopers would have attacked a force four times their number. British troops were arguably the hardest to break with cavalry charges and their firepower was acknowledged as the deadliest in Europe. As the French were learning, the new Portuguese army was proving as tough and deadly on the battlefield as the British. It is impossible to know what the outcome of the charge would have been, but the strong suspicion must be that the Allied troops would have repulsed Monbrun’s and Lepic’s cavalry.

The great French cavalry attacks to the south had driven the British back to a new defence line that was actually less extended than their initial positions. This new line continued to protect the southern flank so that Masséna’s troops could not relieve Almeida. The bulk of Wellington’s army, mostly deployed behind Fuentes de Oñoro still had to be vanquished if the French were to prevail. Masséna ordered six divisions to attack the village and its immediate area across a 1.5-km front. This was a powerful attack force, but the target was a formidable defensive position. The low stone houses, narrow winding streets and the hills just behind it were ideal spots in which the Anglo-Portuguese defenders could dig in.

On the plateau behind the village further west was Spencer’s 1st Division, then Picton’s 3rd Division and Ashworth’s Portuguese Brigade. In the village were the 1/71st Foot and 1/79th Foot with the 2/24th Foot on the hill just behind and ready to reinforce the two Highland battalions within minutes. Craufurd’s Light Division had been withdrawn to form the reserve. Wellington, who enjoyed superiority in artillery, had also concentrated six batteries in the area. When the French artillery posted to the northeast of Fuentes de Oñoro opened up to ‘soften up’ the area for the attack, the Anglo-Portuguese batteries answered with such potent counter-battery fire that the fire of the French gunners soon became ineffective.

The French cavalry had been in action to the southwest for about two hours (since dawn) when Masséna, saw in the distance what was apparently his troopers sweeping all before them and ordered the assault on Fuentes de Oñoro. The attack was launched by the 4,200 men of Ferey’s Division of 6th Corps, which was holding the few houses east of the small Dos Casas River. The French were initially successful, driving the 71st and 79th back about halfway into the village but the assault was checked by the arrival of the 24th Foot. To support the attack, General Drouet called upon his shock troops – three battalions made up of 18 companies of elite grenadiers drawn from both Divisions of his 9th Corps. Wearing their tall bearskin caps, these grenadiers now pushed into the village and renewed the attack, driving the three British battalions back towards the church at the foot of the hill. Wellington, seeing the increased pressure on this critical point, ordered the light companies – the same that had fought in the village two days earlier – to reinforce the men in the village. They were followed by the entire 6th Cazadores. A ferocious struggle ensued in the village’s streets with no clear advantage to either side.

To break the deadlock, General Drouet decided to commit the 10,000 men from Conroux’s and Clarapède’s divisions for a final sweep through the village and up to the plateau so as to smash Wellington’s centre. As many as ten French battalions – about 6,000 men – charged into Fuentes de Oñoro to assist their grenadier comrades. They ran through lanes already choked with the dead and wounded. The British and Portuguese soldiers fought back fiercely but had to retreat in face of superior numbers. The French 9th Light Infantry got past the little church and to the foot of the hill behind it. Just beyond was Mackinnon’s Brigade of about 1,800 men made up of the 1/45th, 74th and 1/88th from Picton’s 3rd Division. Sir Edward Packenham was sent to Wellington by Mackinnon to request permission to charge the French.

Wellington perceived that this was the decisive moment and immediately granted Mackinnon’s Brigade permission to charge down into the village. ‘We’ll waste no powder’ Picton said grimly, ‘this business must be done with cold steel.’ A few minutes later, the 1/88th charged down the hill, meeting the French 4/9th Light Infantry in a terrible clash by the church, face to face in a desperate struggle mostly with the bayonet – a street battle of heroic intensity until the French light infantrymen began to give way. The 74th charged down another street and also started driving back the French infantrymen while the exhausted Highlanders and Allied light infantry companies rallied to support the counter-attack. The tide of men surged through the streets in one of the few instances during the Peninsular War when the bayonet was used in a general engagement. The French retreated at every point and fell back across the river to its eastern bank where they halted.

The final, massive assault of the French 9th Corps had been repulsed by the Anglo-Portuguese with much slaughter, and the battle ended at about 2.00pm. The 9th Corps had lost over 800 men and Ferey’s Division some 400 so that French casualties were in excess of 1,200 men. The 74th and 88th lost only 116 men while the 24th, the light companies and 6th Cazadores reported 160 casualties. After the shooting had died down, Picton encountered some men of the 88th and told them ‘Well done 88th!’ to which some answered ‘Are we the greatest blackguards of the army now?’ alluding to his former comments on the regiment. ‘No, no, you are brave and gallant soldiers. This day redeemed your character.’23

Allied casualties suffered during the day amounted to 1,452 officers and men of which 192 were killed, 958 wounded and 255 taken prisoners. The French had 2,192 casualties of which 267 were killed, 1,878 wounded and 47 taken prisoners. Most of the French artillery’s guns were put out of action by the Allied guns.

The southwestern battery at the fortress of Almeida. Its French garrison managed to slip out in May 1811. (Photo: RC)

The final event of the campaign concerned the French garrison stranded in the fortress of Almeida. As the French army withdrew into Spain, Masséna sent messengers to Almeida with instructions to abandon the place and try to escape undetected. Two of the three messengers were disguised as peasants but were caught and shot as spies. The third messenger remained in uniform and got through to Brigadier-General Antoine-François Brenier, governor of Almeida. The place was surrounded by Pack’s Portuguese Brigade until 10 May, when it was relieved by Campbell’s 6th Division. Meanwhile, in the city, the French spiked guns and placed mines to ruin the fortifications. On the night of 10/11 May, Brenier and his 1,300 men slipped out quietly in two columns. They ran into piquets of the 1st Portuguese Infantry and the 2nd Foot which were quickly scattered. Just at that moment, tremendous explosions rocked Almeida, attracting the attention of the Allies so that Brenier and his men slipped through more British troops after some fighting and joined Masséna’s army. It was a setback for Wellington, who was very upset. Neither Generals Campbell or Erskine had deployed their troops in a tight enough noose around the city. The French lost about 350 men in the fighting but, in Wellington’s opinion, it was a disgrace that any should have escaped at all.

Nevertheless, the last of the French troops had finally left Portugal. A few hours before, on 11 May, Marshal Marmont arrived to replace Masséna.

20 The 17 light companies were drawn from the 2/24th, 2/42nd, 1/45th, 1/50th, 1/71st, 74th, 1/79th, 2/83rd, 1/88th, 2/88th, 1/92nd, 94th, the 1st, 2nd, 5th and 7th line battalions of the King’s German Legion, the 9th and 21st Portuguese infantry.

21 William F.P. Napier, History of the War in the Peninsula and in Southern France, Vol. II, book XII. The event inspired a number of paintings, several of which appear in this book.

22 The French accounts of this success are rather quaint. Fririon mentioned that ‘300 Hussars [!] of the English Royal Guards’ had been captured. A. Hugo’s France Militaire, IV, was even better, stating that Monbrun’s charge on the ‘English Royal Grenadiers’ had broken through and sabred their two squares and taken ‘1,200 prisoners, but only could bring part of them back’...!

23 As quoted in Arthur Griffiths, The Wellington Memorial (London, 1897), p.330. The 88th and 74th who charged with the bayonet suffered amazingly few fatalities. The 1/88th had one officer and one private killed, the 74th had one officer and two privates killed. The wounded consisted of two officers and 47 men of the 1/88th, two officers and 54 men of the 74th (Oman, IV).