‘A MANIFEST MIRACLE OF GOD’ (1398–1399)

For most of the eight months he spent in Paris, Henry was based at the Hôtel de Clisson, at the heart of the city near the Temple. The welcome he received from King Charles VI and the princes of the blood was generous, and there was even talk of a possible marriage between him and Mary, the widowed daughter of the duke of Berry.1 Richard, alarmed, sent the earl of Salisbury to Paris to remind the French king that Henry was a traitor, and when Duke Philip of Burgundy repeated Salisbury's words in Henry's hearing it caused a row between them, although Charles protested that Henry had been treated unfairly.2 Yet if the French took a dim view of Richard's machinations against Henry, accusing him of secretly coveting the Lancastrian estates, the English king could point out that Henry's failure to disentangle himself from the undergrowth of factionalism which had sprung up around the intermittently insane Charles did little to smooth the path of Anglo-French diplomacy.3 Whether or not it was Henry's decision to stay at the Hôtel de Clisson, it was a decision with implications: its builder, Olivier de Clisson, one of the towering figures of French politics during the last thirty years of the fourteenth century, was the inveterate foe of England's ally John de Montfort, duke of Brittany; as one of the ‘Marmousets’ who had excluded the royal uncles from power between 1388 and 1392, he was also hated by the dukes of Berry and Burgundy, who toppled him from power following Charles's first attack of madness in 1392.4 This, however, only drove Clisson into the arms of the king's brother Louis, duke of Orléans, with whom he concluded a pact in October 1397 – in reality, a pact against Philip of Burgundy and his clients, who by now dominated the royal council. Philip was the English king's main ally at the French court and the architect on the French side of the twenty-eight-year truce of 1396. Louis of Orléans, by contrast, advocated a more robust cross-Channel policy, drawing into his orbit men such as Clisson who had waged decades of often successful warfare against the English.

Clisson was only rarely in Paris these days, but he and Henry were in contact.5 Around Christmas time, there was a rumour that the two of them, together with Louis of Orléans and John, count of Nevers, were planning an expedition to Avignon and Milan where, with the help of Duke Gian Galeazzo (Louis's father-in-law), they would effect a reconciliation between the Roman and Avignonese popes.6 Henry's friendship with Orléans was also well known: they often supped together, and in late January 1399 Louis entertained Henry and Mary de Berry at his castle of Asnières (Normandy), apparently to encourage their relationship.7 Yet their alleged initiative on the Schism, the most contentious issue in French politics and one of the many which divided Orléans and Burgundy, can hardly have received the blessing of either the French or the English king,8 and it is easy to see why Richard felt constrained to take counter-measures. Salisbury's mission to Paris was one such move; another was Richard's decision in October 1398 to retain a man whose reputation for thuggery outstripped even that of Clisson. Pierre de Craon, Lord of Ferté-Bernard, had fled France following a bungled attempt to assassinate Clisson in the rue de Saint-Pol, just yards away from the royal palace, in June 1392 and eventually made his way to England where, on 15 October 1398, two days after Henry left Dover to begin his exile, the English king retained him at the extravagant price of £500 a year for life.9 His infamy notwithstanding, Craon still had powerful friends at the French court, and they were not the same men as those whom Orléans or Clisson counted as their friends. In February 1399 Richard sent Craon and the royal under-chamberlain, Sir Stephen Le Scrope, to Paris on ‘secret affairs’, that is, to assess the state of French politics.10

If Richard made sure to keep abreast of developments in France, Henry also kept in touch with events in England. He exchanged letters with his father, who continued to offer him advice until, around Christmas, the fifty-eight-year-old Gaunt fell ill.11 He died on 3 February 1399 at Leicester castle, deeply depressed on account of the uncertainty surrounding his son's future and that of the Lancastrian inheritance.12 His will included the unusual provision that his body should remain unburied for forty days after his death, and thus it was not until 16 March that he was interred next to the high altar in St Paul's cathedral in London beside Henry's mother, Duchess Blanche.13 This was, Henry knew, a pivotal moment both for Richard and for himself: would the king keep his word and let him sue for livery of his father's estates, or would he succumb to the temptation to sequester the Lancastrian inheritance? The answer was not long in coming. A week before the funeral, at a council meeting at King's Langley (Hertfordshire), Richard made the decision to extend Henry's ten-year exile to a life sentence, and take possession of his father's lands. William Bagot, who was there, promptly sent a messenger to Paris informing Henry of the king's decision and advising him to ‘help himself with manhood’,14 so that by the time it was announced publicly on 18 March it is likely that Henry already knew his fate. Richard's pretext was that Henry's request to be permitted to sue for livery of any lands that might fall to him, granted to him in the aftermath of the judgment at Coventry, had been contrary to the terms of that judgment, which had forbidden him to petition for any mitigation of his sentence.15 Two days later, on 20 March, Richard also denied Henry the stewardship of England, an office held by the house of Lancaster for over a hundred years.16

Thus began the final crisis of Richard's reign. Popular support for his regime had been eroding for some time. Demonstrations of loyalty for victimized magnates – by the Mortimer retainers, for example, who turned out in their thousands to greet the earl of March on his arrival at Shrewsbury, all dressed in his livery, or by the one thousand and more well-wishers who gathered on the quayside at Lowestoft to give Thomas Mowbray a rousing send-off in October 1398, or by Thomas Geldesowe of Witney, one of the leaders of an uprising in the Thames Valley in the spring of 1398, who adopted ‘Thomas, the young earl of Arundel’ as his nom de guerre – were matched by local opposition in Warwickshire, Gloucestershire and elsewhere to upstart royal favourites such as Thomas Holand, the newly created duke of Surrey, and Thomas Despenser, now earl of Gloucester.17 Shortly before the aborted duel at Coventry, Richard issued orders to deal severely with any persons found defaming the king or his royal dignity.18 His bodyguard of Cheshiremen, the archers and yeomen of the crown who by early 1399 numbered at least 760 and possibly up to 2,000, were especially disliked, not just for their wanton violence but also for their unbefitting intimacy with the king: for every livery badge of the white hart that the king handed out, punned the author of Richard the Redeless, he lost ten loyal hearts.19 The blank charters which the king demanded from London and the seventeen counties closest to the capital aroused suspicion and dismay: the Londoners, said one citizen, were all ‘indicted as rebels’ by being forced to seal admissions of guilt accompanied by pleas for forgiveness, ‘and no man knew what it meant’. The day after seizing Henry's inheritance, the king issued a general prohibition against letters being sent out of the realm.20

Richard knew that it was in Paris that the likeliest threat to his kingship lay, and initially he tried to mollify Henry, allowing him to collect his income from Mary de Bohun's lands and promising him £2,000 a year from the treasury.21 When Gaunt died, he sent an esquire to Paris to inform him.22 Yet all this was as nothing when set against the blows the king inflicted on him in March 1399. To many, Richard's decision confirmed that it was his purpose all along to bring down the house of Lancaster, thus allowing Henry to present himself as the champion of property rights against a perjured regime.23 A contemporary poet excoriated Richard's cronies as ‘gentlemen from the dung (de stercore)’ and called on ‘the eagle duke . . . Henry of Lancaster, our light, our glory, our friend’ to return and, together with Christ, save the people and ‘have the villains drawn and beheaded’ – the villains being Bussy, Bagot, Green and Le Scrope.24 Henry must have been aware of such sentiments. Letters passed regularly between him and his council in London, and he knew that Richard was planning to go to Ireland, taking with him not only the hated Cheshire bodyguard but also several of his leading supporters among the remodelled upper nobility. His opportunity would come.

A concatenation of events in the early summer strengthened Henry's hand: Thomas, the son and heir of the earl of Arundel, escaped from the custody of the duke of Exeter and fled abroad to join his uncle, the exiled archbishop of Canterbury.25 After leaving England in October 1397, Archbishop Arundel had initially made his way to Ghent, then to Rome, where he incurred Richard's wrath by asking the pope to restore him to his see, and then, by January 1398, to Florence, where he remained for a year or so before returning north and spending time at Cologne and Utrecht.26 By early June at the latest, uncle and nephew had moved to Paris to join Henry. This was an act of defiance in itself, for Henry's sentence of exile had forbidden him any contact with the former archbishop. Richard had a healthy respect for Arundel,27 a man of nimble intellect and sharp tongue: he had berated the king to his face at least twice in the past, and would do so again.28 Yet it cannot have been an easy moment: the last time Henry and Arundel had met was at the September 1397 parliament, where Henry had helped to secure the conviction for treason of Arundel's brother and Gaunt had pronounced sentence of death on him. Walsingham reckoned that the archbishop's willingness to forgive if not forget must have required supernatural intervention.29 In the event, Henry and Arundel's reunion in Paris marked the forging of a partnership not merely for a revolution but for a reign.

Events in France also moved in Henry's favour. The dukes of Burgundy and Berry both moved out of the city before the end of May, either to escape an outbreak of plague or in frustration at the behaviour of the duke of Orléans. The latter's influence at the French court was now paramount.30 On 17 June, by which time news would have reached Paris that Richard had crossed to Ireland, Henry and Orléans drew up a treaty of alliance.31 On the face of it, this infamous (as it became) document appears unexceptionable. It bound Henry and Louis by mutual oaths to support each other's friends, oppose each other's enemies, uphold each other's honour and well-being, and come to each other's help in times of war or unrest, for as long as the Anglo-French truce remained in place. The exclusion of named individuals, including the kings of France and England and the duke of York,32 sought to allay any suspicion that it was a treaty directed against any of those persons. Yet suspicion there was, and given the timing that is not surprising. Henry would later claim that he had revealed his plans in full to Orléans, who had approved them and promised aid against Richard, and there were many in France who believed him, for the alliance seemed to guarantee, at the minimum, French connivance at the enterprise he was about to undertake. Orléans's reasoning is less easy to explain, but he probably found his territorial ambitions in southern France thwarted by the Anglo-French truce and hoped to foment trouble for the English king and the duke of Burgundy.33 Whether he truly believed that Henry would succeed in overthrowing Richard is another matter, although he must have realized that it was a possibility; while it is unlikely that Henry was actively aided by Orléans or anyone else in France, relations between the French and English courts had already cooled markedly since the heady days of 1396.34 Nevertheless, Henry covered his tracks: stopping off at Saint-Denis on his way to the coast, he let it be known that he was planning to travel to Spain. As far as can be gathered, he was allowed to board an English merchantman at Boulogne without any attempt being made to stop him.35 Within two weeks of sealing his alliance with Orléans he was back in England.

The success of the revolution of 1399 is explicable in part by the absence of the king, his Cheshiremen and his magnates in Ireland, and in part by the element of surprise Henry achieved.36 It was much more than a personal triumph: it was the vindication of the Lancastrian affinity, of loyalties and affiliations which had been nurtured and tautened for decades and generations to the point where they were able to withstand both the blandishments and the bullying of a king such as Richard. Since taking control of the duchy, Richard had done what he could to break the nexus between the affinity and its lord. Annuities paid by Gaunt to some ninety of his former retainers were not confirmed unless they agreed to ‘stay with the king only’, while the duke's estates were placed in the hands of those whom the king regarded as his most dependable supporters, although it soon became apparent that they had failed to inspire any personal allegiance among their new tenants.37 The investment which successive earls and dukes had ploughed into the Lancastrian corporation – an ongoing process, for Henry distributed 192 livery collars and 27 crescent badges in the summer of 1399 – now paid its dividend.38 Richard could neither buy nor command its defection.

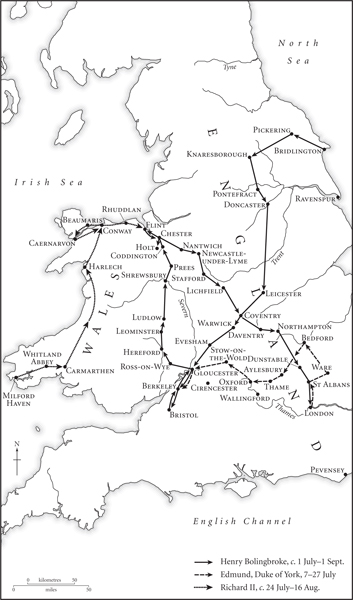

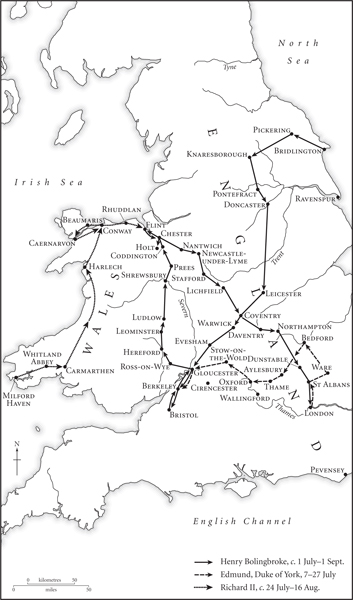

It was doubtless the confidence he placed in his father's affinity that persuaded Henry to land in Yorkshire.39 Putting in first at Cromer in Norfolk (a duchy property) to pick up supplies, then around 30 June at Ravenspur, an abandoned settlement at the mouth of the Humber where a hermit was later permitted to build a chapel to mark the spot, he eventually disembarked at Bridlington or a point close by, hoping presumably to enlist the aid of his favourite saint for his enterprise.40 Among the first to join him were Robert Waterton, steward of Pontefract, bringing with him 200 foresters from Knaresborough, and the Yorkshire knight Sir Peter Bukton, former steward of his household.41 The force Henry had brought with him from France consisted of a few dozen persons at most, and although it included experienced soldiers such as Erpingham, Rempston, de Courte and Norbury, it was in no sense an army of invasion. As a banner to rally the discontented, however, it served its purpose admirably. Henry himself, Archbishop Arundel, and the son of his beheaded brother were potent symbols of the warped judgments of Richard's later years. That the Lancastrian affinity would rally to Henry's cause might have been expected, but equally reassuring to Henry must have been the speed with which magnates such as the earls of Northumberland and Westmorland and Lords Willoughby, Greystoke and Roos came out against the king, and the fact that the citizens of York and Hull loaned him money to pay his troops. By the middle of July, the platoon-sized force which had beached at Ravenspur at the end of June had been transformed into an army several thousand strong.42

Although localized acts of resistance to Richard's regime broke out with remarkable speed,43 Henry remained wary during the first two weeks after his landing, moving from one duchy castle in Yorkshire to another (Pickering, Knaresborough, Pontefract); only once his level of support became apparent did he advance more rapidly southwards. At Leicester, around 20 July, he recruited followers from his father's Midland honours and from the retainers of the earl of Warwick.44 So far, he had encountered little resistance,45 but what the keeper of the realm would do was unclear. News of an impending invasion had reached Westminster on 28 June, prompting the duke of York to order the sheriffs to raise troops and join him at Ware (Hertfordshire) as soon as possible.46 As yet, York had little idea where the danger lay – the south coast and the west country both featured in his earliest plans – but by 7 July, when he left London for St Albans, he knew that Henry had landed in Yorkshire. On 12 July he moved to Ware to collect his troops, and by 16 July he had arrived at Oxford, where further contingents joined him.47 At its peak, his army consisted of around 3,000 men, but his position was weak. News of the ‘wondrous events’ in the north filled the land. ‘The eagle is up and has taken his flight’, enthused one poet, and ‘with him he brings the colt of the steed’ (the son of the earl of Arundel); the bush would be cropped (Bussy), the grass mown (Green) and the ‘great bag’ cut down to size (Bagot).48 The author of Richard the Redeless characterized Henry alternately as the eagle, the falcon or the greyhound. The poem opened in July at Bristol, where the author was praying in the church of the Trinity when rumours began to circulate that, while Richard ‘warred in the west’, Henry, a man whom ‘all the land loved throughout its length and breadth’, had landed in the east ‘to right his wrong, so that he should later do likewise for [the people]’. ‘Now, Richard the Redeless (ill-advised)’, chided the author, ‘take pity on yourself, you who led your life lawlessly and your people as well’, for Henry ‘has entered into his own’, and ‘covetousness has crushed your crown forever’.49 Sympathy for Henry's cause could also be found among the duke of York's troops, some of whom bluntly informed him that they would not partake in an attack on Henry, while York himself is said to have declared that he had no intention of attacking someone who had come to ask for the restoration of his rightful inheritance.50 Thus even as his army was mustering, it began to disintegrate, desertions multiplying as the invader approached. Money was not York's problem: he handed out over £2,000 to his captains and promised a good deal more. Yet there were many, as Walsingham put it, who, having accepted payment, ‘set off to find the duke of Lancaster and to fight with him at the wages of King Richard’.51 By about 20 July the keeper's position was becoming untenable. Hoping to make contact with Richard's army when it returned from Ireland, he sent his fellow councillors (Bussy, Le Scrope, Green, Bagot and John Russell) to Bristol, while he himself moved northwards via Stow-on-the-Wold to Gloucester and Berkeley, a route designed to effect a meeting with Henry.

Map 3 The revolution of 1399

Meanwhile Henry had arrived at Warwick castle on 24 July to discover that the duke of Surrey had placed a crowned hart of Richard II's livery and a white hind of his own livery atop the castle gate, both of which he demolished – the clearest signal yet that his ambitions extended beyond the restoration of the duchy of Lancaster.52 Publicly, Henry claimed that he had returned merely to claim his rightful inheritance, a cause which he knew would unite support behind him, and it was later asserted that he had sworn ‘upon the relics of Bridlington’, as well as at Doncaster when he was joined by the Percys, that this was all he would claim.53 Yet it is hard to believe that it did not cross the minds of those who marched with him in the summer of 1399 that their support was likely to have more thoroughgoing consequences. Left to rule, Richard might bide his time, but ultimately he would seek revenge, as he had in 1397–8; despite claims to the contrary later made by the Percys and others, his deposition was surely seen as the likeliest outcome of a successful military campaign by Henry. More contentious was the question of who would succeed him, to which Henry probably gave answers that were at best ambiguous and more likely mendacious.

Crossing the Severn at Gloucester,54 Henry arrived on Sunday 27 July at Berkeley, where he and York ‘came to an agreement’ in a chapel outside the castle.55 Exactly what this entailed is not recorded, but the outcome is clear: York abandoned his attempt to resist Henry's progress by force. Henry may have been asked to give certain undertakings in return, but it was probably too late for that by now. A few Ricardian die-hards such as Henry Despenser, bishop of Norwich, were placed under arrest, and on the following day the two dukes moved on to Bristol. Bagot had escaped to Ireland, but Le Scrope, Bussy, Russell and Green were still in the castle. Surrendered by the garrison, they were kept in custody overnight and tried before a military court on the morning of 29 July. Russell was spared, feigning insanity, but Le Scrope, Bussy and Green were convicted and beheaded; had they not been, it was said that the mob would have ‘broken them into little pieces’.56 In Henry's eyes they were guilty specifically of betraying him and his father, for Le Scrope came from a family with a tradition of service to the dukes of Lancaster, while Bussy and Green had both been Gaunt's retainers for nearly two decades, yet all three had been accomplices to the seizure of his inheritance.57 York's role at Bristol was telling: as keeper of the realm, he not only attended the execution of the king's councillors but used his authority to order the surrender of the castle.58 Indeed it was probably on his formal authority that they were tried, although in practice it must have been Henry's decision. From now onwards, Henry increasingly acted as if he were already king of England, even if he continued to preserve the fiction that he was acting in Richard's name. Yet by 2 August, when Henry appointed the earl of Northumberland to be keeper of Carlisle castle and warden of the West March of Scotland, offices manifestly in the gift of the crown, and sealed the appointment with the duchy of Lancaster seal, the line separating his de facto and de jure authority must have seemed to many to have faded almost to vanishing point.59

The fact remained, however, that Richard was still at large and, so far as Henry knew, in possession of an army. The king had arrived back from Ireland at Milford Haven (Pembrokeshire) around 24 July. A week later he had reached Carmarthen and made contact with some of the duke of York's officials, who probably told him of the startling transformation in his and Henry's fortunes. Deciding that he could not risk an armed confrontation – for the army which he commanded was but a shadow of the force which he had led to Ireland two months previously, storms and delays having scattered his fleet to a variety of ports – he made instead for North Wales, whither he had already despatched the earl of Salisbury to raise support and which was sufficiently close to Cheshire to offer the chance of a counter-attack or at least a refuge.60 In the interests of speed, he left his army behind, slipping away with just a dozen followers on the night of 31 July, dressed as a priest according to one account.61 When Aumale and Worcester awoke to find him gone, they disbanded the royal household, dismissed the army and made their way to Chester to submit to Henry.62

Henry's decision to make for Cheshire, Richard's inner citadel, made good sense. Marching along the Anglo-Welsh border during the first week of August, a route parallel to that of the king about sixty miles to the west, he encountered isolated pockets of resistance, but nothing to slow his progress apart from the daily influx of renegades from Richard's Irish army such as Robert Lord Scales, Thomas Lord Bardolf and (once he reached Chester) Aumale, Worcester, and Lords Lovell and Stanley.63 Yet according to Adam Usk the most welcome recruit to Henry's cause was no earl or peer but a greyhound, credited by the chronicler with an unerring instinct for the mutability of political fortunes. After the death of its first master, the earl of Kent, in 1397, the dog had found its way by instinct to Richard, with whom it remained day and night for two years, but when the king abandoned his army at Carmarthen it promptly deserted him and ‘once again by its own instinct, alone and unaided’, made its way to Shrewsbury, where it ‘crouched obediently before Henry, whom it had never seen before, with a look of the purest pleasure on its face’. Delighted at such a happy augury, Henry allowed it to sleep on his bed, and later, when brought once again into Richard's presence, it failed to recognize him.64 Also at Shrewsbury, where he spent the nights of 5 and 6 August, Henry received the submission of Chester, conveyed to him by Sir Robert and Sir John Leigh, members of the family which more than any other had been influential in promoting the king's interests there.65 For Richard, this represented the closing of the last window of hope, but it also disappointed some of Henry's own followers, whose hatred for Cheshire and its people had encouraged them to join him in the hope of plundering the county, but who now returned to their homes. In fact they were over-hasty. Despite promising to spare Cheshire, Henry was either unable or unwilling to prevent it being ravaged once his army entered the county on 8 August: crops were wasted, booty seized, chapels stripped of their valuables and exemplary retribution exacted. Three days after his arrival, Perkyn Leigh, a hero to many Cheshiremen and the leading royalist in the city, was summarily beheaded and his head set up on a stake outside the east gate of the town.66 For two weeks Henry's army occupied Chester, destroying houses and looting whatever weapons or provisions they cared to seize. The city chamberlain's account claimed that his men had seized 400 bows, large quantities of arrows, bowstrings, lance-heads, crossbows, baldrics and quarrels from the castle, along with substantial quantities of wine and salt.67

Meanwhile, the king and his small band of devotees had made their way northwards from Carmarthen, keeping close to the coast, and arrived at Conway castle around 6 August, but no army awaited him, only the hundred or so men who had accompanied Salisbury from Ireland.68 ‘Downcast and miserable’, Richard had with him the dukes of Exeter and Surrey, the earl of Gloucester, three bishops including Thomas Merks of Carlisle, and half a dozen or so servants and soldiers including the redoubtable Navarrese esquire Janico Dartasso. In the hope that something short of unconditional surrender might yet be negotiated, Exeter and Surrey were sent to parley with Henry. Exeter advised Richard to confront Henry directly, to offer him his inheritance and remind him of the shame which would fall upon his head should he depose a lawful king. There was apparently still a belief, or at least a hope, that the army left behind at Carmarthen might rejoin them in the north, but within a further day or two a messenger arrived from South Wales to inform the king that his Irish army had disbanded, which plunged Richard into another slough of despond. Believing Conway to be threatened, he decamped, first to Beaumaris on Anglesey, then to Caernarvon, possibly thinking to escape by ship, possibly searching for the safest refuge. The castles were unfurnished and unprovisioned: there was only straw to sleep on and barely enough to eat. Richard, ‘his face often pale’, cursed the day that he had decided to go to Ireland, but if he seriously thought of fleeing overseas, which he probably could have done, something or someone persuaded him not to; by 15 August at the latest, he was back at Conway to await the return of Exeter and Surrey.

They never did return. On arrival at Chester, Exeter began confidently by urging Henry to beg Richard's pardon for his ‘outrage’ in returning from exile, which, he assured Henry, would be freely granted, but he was quickly brought down to earth.69 Cutting off his brother-in-law almost in mid-sentence, Henry told the two dukes that he had no intention of allowing them to return to Conway. Surrey was locked away in Chester castle, Exeter detained in Henry's household, although when he pleaded too insistently to be allowed to leave, Henry banished him from his presence. The next day or two were spent conducting a lightning raid on Holt castle, eight miles south of Chester, a former Arundel castle which was now the king's principal treasury in the north-west, where Henry seized at least some of the very substantial quantities of money and plate.70 Returning to Chester around 12 August, he despatched the earl of Northumberland and, possibly, Thomas Arundel, to Conway to lure Richard out of the castle.71 What happened next was disputed at the time and still is. The Lancastrian version of events was that Richard, while still at liberty at Conway, promised Northumberland and Arundel that he was willing to abdicate and asked them to set up a committee to determine how this might best be done.72 Creton, however (who fails to mention Archbishop Arundel's presence at Conway), said that Northumberland tricked Richard out of Conway by swearing on the host that he would not be deposed as long as he agreed to restore Henry to his inheritance and to the stewardship of England, and to submit five of his councillors to trial in a parliament at which Henry, by virtue of his office as steward of England, would act as ‘chief judge’; having thus inveigled the king out of Conway, the earl ambushed him (he had concealed his troops behind an outcrop a few miles down the road) and led him to Flint to await Henry's arrival.73

Creton's story is surely closer to the truth. That Richard willingly agreed to abdicate at Conway is most unlikely, although it is possible that he agreed to remain king in name while effective power would be devolved to Henry. Equally problematical is Northumberland's role: he later claimed that Henry had deceived him, having initially sworn that Richard would not be deposed but would remain king ‘under the direction, and by the good advice, of the lords spiritual and temporal’.74 Northumberland's feelings towards the house of Lancaster were ambivalent: he had quarrelled bitterly with Gaunt in 1381 and resented the duke's interference in the affairs of the Anglo-Scottish Marches. More to the point, perhaps, his son Hotspur was married to Elizabeth, aunt of Edmund Mortimer, whom many regarded as the rightful heir to the throne should Richard be deposed; if Henry made any promises to Northumberland, they are more likely to have concerned the succession than the question of whether or not the king had to go. Like Henry, Northumberland knew that sooner or later Richard would seek revenge. Realistically, Northumberland, Henry, and perhaps Arundel must all have told a succession of lies in order to get their hands on the king – although there was probably no other way that they could have done so, and according to Creton Richard also lied, consoling his followers that he would never allow them to be brought to trial in parliament and would assuredly be avenged upon his enemies. Within another few hours, however, by late morning on Friday 15 August, he had fallen into Northumberland's hands, and his assurances counted for nothing.75

When he realized he had been led into a trap, Richard asked to be allowed to return to Conway, but the earl would have none of it: ‘Now that I have you here,’ he replied, ‘I will take you to Duke Henry as soon as I can, for you must know that I promised this to him ten days ago.’76 After a midday meal at Rhuddlan, the party moved on to Flint on the estuary of the Dee, where they spent the night. Henry arrived the following day, his army ‘marching along the sea-shore, drawn up in battle array’, while Richard stood on the battlements and watched them approach. A small detachment including Archbishop Arundel, Aumale and Worcester broke off from the main host and came up to the walls; Aumale and Worcester, Richard could not help noticing, no longer wore his livery but Henry's. The archbishop entered the castle first. Descending from the keep, Richard greeted him in the courtyard and the two men had a long conversation. Creton said that Arundel comforted the king and told him no harm would come to him, but another account of their exchange stated that Arundel told Richard he was ‘the falsest of all men’, that he had sworn upon the host that no harm would come to his brother the earl, and that ‘You have not ruled your kingdom but ravished it [and] by your foul example you defiled both your court and the kingdom.’77 Henry, meanwhile, had ordered his troops to surround Flint, but agreed to wait until the king had dined.78 Eventually, fully armed apart from his bascinet, he passed through the gate and Richard came out to speak to him. Both men removed their headwear, and Henry bowed twice ‘very low’. Richard spoke first: ‘Fair cousin of Lancaster, you are right welcome.’ Henry's reply was to the point: ‘My lord, I have come sooner than you sent for me, and I shall tell you why: it is commonly said among your people that you have, for the last twenty or twenty-two years, governed them very badly and far too harshly, with the result that they are most discontented. If it please Our Lord, however, I shall now help you to govern them better than they have been governed in the past’; to which Richard answered, ‘If it please you, fair cousin, it pleases us as well.’ These were, according to Creton, their exact words,79 and for the moment there was no more to be said. Henry called out (‘in a stern and savage voice’) for horses, whereupon two derisory little nags were brought forward, one for Richard, the other for the earl of Salisbury, to whom Henry, remembering his visit to Paris a few months earlier, refused to speak. Leaving Flint two hours after midday, they reached Chester before nightfall, where the king was jeered by the mob before being locked in the keep with a few close friends, including Salisbury and the bishop of Carlisle. No one else was permitted to speak to him; it was the evening of Saturday 16 August, and his reign had effectively ended. It had taken Henry less than fifty days to conquer both king and kingdom, exulted Walsingham, ‘a manifest miracle of God’.80

1 Saint-Denys, ii.674 (‘as long as he remained there, he was lodged in royal residences, lavishly provided for, along with his retinue, at the king's expense, and loaded with gifts’). Chronographia Regum Francorum (iii.166) said that Henry also visited Meaux, just east of Paris, at some point.

2 Oeuvres de Froissart, xvi.141–9; Salisbury was in Paris from late October to early December 1398: E403/561, 18 October; J. Laidlaw, ‘Christine de Pizan, the Earl of Salisbury and Henry IV’, French Studies 36 (1982), 129–43.

3 The chronicler of Saint-Denis said Henry befriended the duke of Berry, but Berry was not in Paris for much of the time Henry was there: from early August 1398 until 9 February 1399 he remained on his estates in Berry and Auvergne. Nor did he favour Henry's marriage to his daughter (F. Lehoux, Jean de France, Duc de Berri (3 vols, Paris 1966), ii.394–407).

4 The Hôtel de Clisson, built around 1370, was a monument to the wealth and power of this former constable of France: J. Henneman, Olivier de Clisson and Political Society in France under Charles V and Charles VI (Philadelphia, 1996); Lehoux, Jean de France, ii.201.

5 He was in Paris in April 1399, however, at the Parlement (Henneman, Olivier de Clisson, 171, 191, 304).

6 Note Henry's earlier request to take Henry Bowet to Lombardy, above, p. 117. P. Pietresson de Saint Aubin, ‘Documents inédits sur l'installation de Pierre d'Ailly à l'évêché de Cambrai en 1397’, Bibliothèque de l'école des Chartes (1955), 121–2, 138–9; CR, 26–9. John of Nevers was the son of Philip, duke of Burgundy; it was said that Burgundy and Orléans had settled their differences, but this was optimistic. The possibility of a marriage between Henry and Lucia Visconti, Gian Galeazzo's cousin, was also still being discussed as late as May 1399.

7 Oeuvres de Froissart, xvi.116, 137; E. Collas, Valentine de Milan, Duchesse d'Orléans (Paris, 1911), 253; BL Add. Charters 3066, 3404. Duchess Valentina gave Henry a diamond and a set of seven enamels on this occasion, costing 862 francs; she also gave two diamonds worth 30 francs each to two of Henry's esquires with him at Asnières on 27 January. See also ‘Histoire de Charles VI, Roy de France, par Jean Jouvenal des Ursins’, in Choix de Chroniques et Mémoires sur l'Histoire de France, ed. J. Buchon (Paris, 1838), 323–573, at pp. 405–7.

8 H. Kaminsky, ‘The Politics of France's Subtraction of Obedience from Pope Benedict XIII, 27 July 1398’, Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 115 (1971), 366–97. Orléans supported Benedict XIII, who supported Orléans's ambitions in Italy: B. Schnerb, Jean Sans Peur, Le Prince Meurtrier (Paris, 2005), 164.

9 Henneman, Olivier de Clisson, 153–4, 169–71; Foedera, viii.52; Craon received £666 13s 4d of this (E 403/561, 6 November, 8 January; E 403/562, 2 May, 13 May, 9 July), and accompanied Richard to Ireland (CPR 1396–9, 553).

10 E 403/561, 21 February.

11 Henry's ministers' accounts show constant messengers between England and Paris (DL 28/4/1, fos. 2r, 4v, 6r, 7r). When Marshal Boucicaut invited him to join an expedition against the Turks to avenge the disastrous defeat by a crusading army at Nicopolis in 1396, Henry sent Sir Thomas Dymmok to ask Gaunt if he ought to go. Gaunt advised against it, saying that if he felt the urge to travel, he would be better advised to visit his sisters in Portugal and Castile. Dymmok took the opportunity to visit Henry's children and make a tour of his English estates (Oeuvres de Froissart, xvi.132–7).

12 Goodman, John of Gaunt, 168, 174, quoting the Kirkstall chronicle. Gaunt had secured a pardon from the king for all his debts on 30 December, and £1,000 in restored tallies on 8 January (CPR 1396–, 467; E 403/561, 8 January).

13 ‘My beloved consort Blanche’, he called her in his will. J. Post, ‘The Obsequies of John of Gaunt’, Guildhall Studies in London History (1981), 1–12, at pp. 2–4, suggests that Henry may have slipped across from Paris for the funeral, but this is most unlikely; several of Henry's letters were dated from London in the spring of 1399, for he had left a seal in the hands of his chief ministers while he was abroad (DL 28/4/1, fos. 2–7).

14 In other words, to take whatever measures he deemed necessary, force included. The messenger was Roger Smart. According to Bagot, Richard vowed that as long as he lived Henry would never return to England. C. Fletcher, ‘Narrative and Political Strategies at the Deposition of Richard II’, Journal of Medieval History 30 (2004), 323–41, has questioned whether Richard did extend Henry's sentence of exile from ten years to life, correctly pointing out that this is not specifically stated in the Record and Process. Yet it is mentioned by two contemporary chroniclers as well as by Bagot, and it seems fairly clear that this was Richard's intention (CR, 75, 97–8, 211–12; Chronicles of London, ed. C. L. Kingsford (Oxford, 1905), 53). Richard retained Bagot that day as a member of his council with an annual fee of £100: CPR 1396–9, 494.

15 CR, 92; identical letters granted to Mowbray in October 1398 were revoked the same day, so when Margaret, duchess of Norfolk, died on 24 March, Richard seized her estates, although Mowbray was her heir.

16 CPR 1396–9, 490 (grant of the stewardship to the duke of York).

17 Usk, 38–9; Usk says 20,000 turned out to greet March, but this is hard to believe (PROME, vii.425; Davies, Lords and Lordship, 71; Saul, Richard II, 442–4; CPR 1396–9, 350, 365). The son of the decapitated Earl Richard of Arundel was called Thomas. For the rising, see Oxfordshire Sessions of the Peace in the Reign of Richard II, ed. E. G. Kimball (Oxfordshire Record Society 53, Banbury, 1983), 82–9; Bennett, Richard II and the Revolution of 1399, 123–4. The rising took place in the same area as the battle of Radcot Bridge a decade earlier.

18 CPR 1396–9, 505 (repeated a few months later: CCR 1396–9, 505).

19 CR, 31–2; Bennett, Richard II and the Revolution of 1399, 123.

20 Historical Collections, 98–101. The blank charters were stored in the royal chancery (CCR 1396–9, 488, 503).

21 Most of this was paid, up until 20 June 1399, plus a gift of 1,000 marks to help him move to Paris. The future Henry V was also given £500 a year plus £148 to pay for his equipment in Ireland (E 403/561, 14 November, 7 December, 21 February, 5 March; E 403/562, 2 May, 6 May, 20 June). Mowbray got £1,000 a year during his exile.

22 The esquire was Peter Breton. This entry appears in the exchequer issue roll under 8 January (E 403/561), but another entry under the same date records payments to messengers to summon lords to Gaunt's funeral, and since Gaunt did not die until 3 February these entries must have been inserted under the wrong date.

23 Richard never got the chance to reveal his plans for the Lancastrian patrimony. In the short term, Gaunt's vast estates were parcelled out between the king's favourites among the higher nobility – the dukes of Aumale, Surrey and Exeter and the earls of Wiltshire and Salisbury – but the door was left open for the young Henry to enter into his inheritance in due course: A. Dunn, The Politics of Magnate Power (Oxford, 2003), 168–77. In April, Henry sent his esquire, Esmond Bugge, to Windsor to try to persuade the king to relent (DL 28/4/1, fo. 6r; CR, 97).

24 Political Poems and Songs, i.366–8 (‘On the Expected Arrival of the Duke of Lancaster’).

25 CPR 1396–9, 214; Thomas was 17 and had been mistreated in Exeter's household, especially by ‘John Schevele’ (Sir Thomas Shelley), who made him perform menial tasks. He escaped with the help of a London mercer, William Scott, and joined the archbishop in Cologne or Utrecht: Historical Collections, 101; CR, 116.

26 Diplomatic Correspondence, ed. Perroy, 238, 240; D. Carlton, The Deposition of Richard II (Toronto, 2007), 75–86; A. Brown, ‘The Latin Letters in MS. All Souls 182’, EHR 87 (1972), 565–73. Arundel thought Florence ‘an earthly paradise’ and struck up a friendship with the Florentine chancellor and humanist Coluccio Salutati.

27 Note John Bussy's comments on Arundel's ingenuity and cunning (SAC II, 80).

28 Knighton, 354–60; CR, 68; CE, iii.382.

29 According to Walsingham, on the night that Gaunt died, his penitent spirit appeared in a vision to Arundel while he was at Utrecht and begged forgiveness for the injustices which he had inflicted upon the archbishop and his kinsfolk; Arundel, moved by such contrition, promised the spirit to pray to God for his soul (SAC II, 122–3).

30 Burgundy was in the Low Countries from May until August. Berry, having quarrelled violently with Orléans, retired to his castle of Bicêtre; Charles VI, apparently, ‘could no longer refuse anything that the duke of Orléans requested’ (Lehoux, Jean de France, ii.414–18).

31 CR, 109–14.

32 As Henry must have known, York had been appointed keeper of England during Richard's absence in Ireland.

33 Saul, Richard II, 406–7, where it is argued that English diplomacy in Italy also hindered his ambitions.

34 Orléans may have acted in a fit of pique, for it was at just this time that some twenty domestic servants of the young Queen Isabella, including her governess, Margaret de Courcy, and her secretary, arrived in Paris, having been deported from England on Richard's orders; this aroused great anger in France and infuriated Orléans, who had a particular affection for his niece. They were given £465 for removal expenses (CR, 110: E 403/562, 10 June).

35 CR, 25–31, 111, 116–17. One French source said that Charles VI permitted him to leave the realm because he said he was going to England to discuss ‘matters concerning peace’ with Richard II (Chronographia Regum Francorum, iii.169). He was carried to England by Thomas Gyles of Dover, who was rewarded with the office of bailiff of Rye for life (HOC, iii.258; CPR 1399–1401, 35). Saint-Denys, ii.706, said that Burgundy heard about unusual maritime traffic around Boulogne and tried to discover what was going on, but Henry avoided detection.

36 E 403/562, 13 May, 12 July: £2,639 for the war wages of 120 men-at-arms and 900 archers from Cheshire going to Ireland with the king (CCR 1396–9, 489–90; D. Biggs, Three Armies in Britain (Leiden, 2006), 65–80).

37 RHKA, 216, 310 (these 90 included 36 of Gaunt's knights and esquires); Dunn, Politics of Magnate Power, 171–2, who suggests that some of Gaunt's ministers may have been transferring duchy revenues surreptitiously to Paris via Lucchese merchants; Walker, Lancastrian Affinity, 177, 231.

38 DL 28/4/1, fo. 15v; these livery badges cost £83.

39 Walsingham said he initially sailed up and down the coastline to test the defences, and a small party of men under John Pelham was landed at Pevensey in Sussex (a duchy castle), where they were still being besieged by a royalist force three weeks later: S. Walker, ‘Letters to the Dukes of Lancaster in 1381 and 1399’, EHR 106 (1991), 68–79.

40 CPR 1399–1401, 209; DL 42/15, fo. 69v; Biggs, Three Armies, 105–9; CR, 133; the hermit was Matthew Danthorpe.

41 Usk, 52–3; Chronica Monasterii de Melsa, ed. E. Bond (3 vols, RS, London, 1866–8), iii.298–9. Some of Henry's retainers may have had advance notice of his intentions: John Davy, a Lancastrian servant, hastened from London to Dover ‘on hearing of the lord's arrival at the end of [June]’, presumably the landing of Pelham and his men at Pevensey (DL 28/4/1, fos. 7v, 15r).

42 Claims that up to 200,000 men joined him are implausible: for the size of Henry's force see CR, 35, 126, 252–3 (to the list on pp. 252–3 should be added the names of John Langford and William Bromfield): (DL 29/728/11987, m. 10, and E 403/564, 28 November). Henry's second son Thomas, aged twelve, was also with him. The 51 men who received around £5,000 of wages for joining him were only the captains of companies, some of whom brought scores and even hundreds of men. For the loans from York and Hull, totalling £433, see CPR 1399–1401, 354.

43 So at least it was later claimed by, for example, the garrisons of Dunstanburgh and Kenilworth, who claimed to have held them in Henry's name from 1 and 2 July; partisans of the earl of Warwick claimed to have seized Warwick castle on 4 July (DL 29/728/11987, mm. 5, 10; DL 42/15, fo. 71r; Mott, ‘Richard II and the Crisis of 1397’, 176).

44 Biggs, Three Armies, 189–94.

45 Although he had some trouble gaining entry to Knaresborough castle (CR, 133).

46 E. H. Pearce, William de Colchester, Abbot of Westminster (London, 1915), 76–7; E 101/42/12; CR, 111.

47 CR, 247–51; Biggs, Three Armies, 139–40.

48 Political Poems and Songs, ed. T. Wright (2 vols, RS, London, 1859–61), i.363–6 (‘On King Richard's Ministers’). Such anthropomorphic livery imagery would have been instantly recognizable: one of the Arundel livery badges was a horse. Likewise, Gloucester was the swan, the earl of Warwick the bear-keeper, and so forth.

49 Political Poems and Songs, i.368–417. Although begun in early July, the poem was not completed until several months later, for Henry had assumed the rule of the kingdom, although Richard is referred to as still alive.

50 CR, 118, 127 (Walsingham was at St Albans and in a good position to know).

51 CR, 118–19, 247.

52 CR, 135–6.

53 CR, 192–3; he was said to have sworn similar oaths at Knaresborough and at Chester (J. Sherborne, ‘Perjury and the Lancastrian Revolution of 1399’, Welsh History Review (1988), 217–41).

54 Henry was at Gloucester on 25 July (DL 28/4/1, fo. 2r).

55 ‘because the duke of York did not have the strength to resist him’ (CR, 127).

56 Ibid., 120, 128. They were not convicted of treason, but of misleading Richard II, and their possessions were seized by Henry ‘through conquest’: see below, p. 442.

57 Walker, Lancastrian Affinity, 266, 270.

58 CR, 120.

59 E 404/15/46. On 31 July, as duke of Lancaster and steward of England, Henry also granted John Norbury all the lands in England of John Ludwyk – a grant in the king's gift (BL Add. Charter 5829).

60 D. Johnston, ‘Richard II's Departure from Ireland, July 1399’, EHR 98 (1983), 785–805.

61 CR, 139.

62 CR, 122, 129, 141. On their way home, the royalist soldiers were harried and despoiled by the Welsh; if they tried to attack Henry's strongholds in Wales and the March, they would have found them well defended. The gates, moat, walls and drawbridge of Brecon castle had been strengthened; the keeper of Kidwelly castle had brought in oil and rocks to hurl at any who might be rash enough to try to assault it, and Hay-on-Wye castle was also reinforced; a detachment of horsemen was sent from Cantref Selyf to Gloucester ‘to defend their lord against his enemies’ (DL 29/548/9240; SC 6/1157/4, mm. 3–4; Davies, Lords and Lordship, 84–5).

63 The intrepid Adam Usk claimed to have persuaded the people of Usk not to harry Henry's army, and to have persuaded Henry to set free and promote Thomas Prestbury, a monk of Shrewsbury whom Richard had imprisoned in Ludlow castle for subversive preaching. Usk provides a vivid day-by-day account of Henry's route-march, noting that he and his followers ‘partook liberally’ of the wine which they found stored along the way. It was Eleanor Holand, Richard's niece and lady of Usk, who tried to organize resistance there (Usk, 52–6; CR, 128–9).

64 Usk, 86–7. A story that so perfectly personified (or at least caninified) the English people's transfer of allegiance from one ruler to another might be dismissed had not Froissart also heard it, although he heightened the drama of the greyhound's defection by placing it at the moment of Richard's capture (Froissart, Chronicles, ed. G. Brereton (Harmondsworth, 1968), 453).

65 CR, 128–9.

66 When Usk went to Coddington chapel on the morning of 9 August, hoping to say mass, ‘I found nothing there except doors and chests broken open, and everything carried off’ (Usk, 56–8; CR, 153–4; Clarke and Galbraith, ‘The Deposition of Richard II’, 163–4).

67 SC 6/774/10, mm. 2d, 3d (items were also taken from Flint and Rhuddlan). The garrison was paid to defend Chester from 3 July to 5 August, ‘on which day the aforesaid castle was, under certain conditions, delivered and handed over to the said duke [Henry]’.

68 For the last two weeks of Richard's freedom, we are largely dependent on the ‘Metrical Chronicle’ of Jean Creton, a valet-de-chambre at the French court who came to England in the spring of 1399 to join the king's expedition to Ireland. When news came of Henry's landing, Creton was sent back to North Wales with the earl of Salisbury and was with the king when he surrendered. For extracts from Creton's chronicle, see CR, 137–52; the whole text is translated in ‘Metrical History of the Deposition of Richard the Second’, ed. J. Webb, Archaeologia (1823).

69 ‘Metrical History’, 121: Creton said that Exeter spoke ‘quite boldly’ to Henry ‘for he had married his sister’, but Creton was not there (Exeter's wife was Elizabeth, Henry's elder sister).

70 For the treasure at Holt, see below, p. 175. Walsingham said Richard also went to Holt at this time, presumably to recover his treasure, but it seems unlikely that the king could have reached the castle and Creton does not mention it (SAC II, 154–5). Part of Henry's thinking was doubtless to prevent the treasure there from being looted by others under cover of the disturbances; some £20,000 of the Despensers' and Baldock's personal wealth was looted during the revolution of 1326–7, and took twenty years to recover (M. Ormrod, Edward III (New Haven, 2011), 47).

71 The archbishop may or may not have gone to Conway: see Sherborne, ‘Perjury and the Lancastrian Revolution’, and Saul, Richard II, 413–16, who thought that he was not there but that ‘a role was created for the prelate in the later narratives to lend a measure of legitimacy to the proceedings’.

72 CR, 169–70.

73 The five councillors to be submitted for trial were the dukes of Exeter and Surrey, the earl of Salisbury, the bishop of Carlisle, and the clerk Richard Maudeleyn.

74 CR, 38–9, 194–5.

75 CR, 146–8.

76 What follows is mainly from Creton's account (CR, 147–51).

77 CE, iii.382; the author thought Henry was already in the castle, and only when he cried ‘Enough!’ did Arundel relent.

78 Creton and his companion took the opportunity to present themselves to Henry at the gate, explaining that they had been sent by the king of France to accompany Richard to Ireland. Henry replied in French, ‘My young men, do not fear, nor be alarmed at anything you might see. Keep close to me and I will answer for your lives.’

79 ‘the very words that they exchanged, no more and no less, for I heard them and understood them perfectly well’ (CR, 149–51).

80 SAC II, 156, 234.