All Sailors must have at least a basic understanding of seamanship. No matter what part of the Navy you serve in, such knowledge will likely serve you well.

Major Topics Covered:

![]()

![]() Working with lines and ropes

Working with lines and ropes

![]()

![]() Mooring with lines and anchors

Mooring with lines and anchors

![]()

![]() Towing

Towing

![]()

![]() Underway replenishment

Underway replenishment

![]()

![]() Boats

Boats

![]()

![]() Types

Types

![]()

![]() Crews

Crews

![]()

![]() Customs

Customs

To Learn More:

![]()

![]() www.usni.org/BlueAndGoldProfessionalBooks/TheBluejacketsManual

www.usni.org/BlueAndGoldProfessionalBooks/TheBluejacketsManual

![]()

![]() Basic Military Requirements (NAVEDTRA 14325)

Basic Military Requirements (NAVEDTRA 14325)

![]()

![]() Seaman (NAVEDTRA 14067)

Seaman (NAVEDTRA 14067)

![]()

![]() Boatswain’s Mate (NAVEDTRA 14343A)

Boatswain’s Mate (NAVEDTRA 14343A)

![]()

![]() Chapman Piloting & Seamanship, 67th ed., by Jonathan Eaton (Hearst, 2013)

Chapman Piloting & Seamanship, 67th ed., by Jonathan Eaton (Hearst, 2013)

![]()

![]() Navy Towing Manual (Naval Sea Systems Command)

Navy Towing Manual (Naval Sea Systems Command)

![]()

![]() Boat Crew Seamanship Manual (COMDTINST M16114.5C) by U.S. Coast Guard (2014)

Boat Crew Seamanship Manual (COMDTINST M16114.5C) by U.S. Coast Guard (2014)

Associated Tabs:

![]()

![]() TAB 12-A: Mooring Line Configurations and Terms

TAB 12-A: Mooring Line Configurations and Terms

![]()

![]() TAB 12-B: Line-Handling Commands

TAB 12-B: Line-Handling Commands

![]()

![]() TAB 12-C: Anchor Chain Identification System

TAB 12-C: Anchor Chain Identification System

![]()

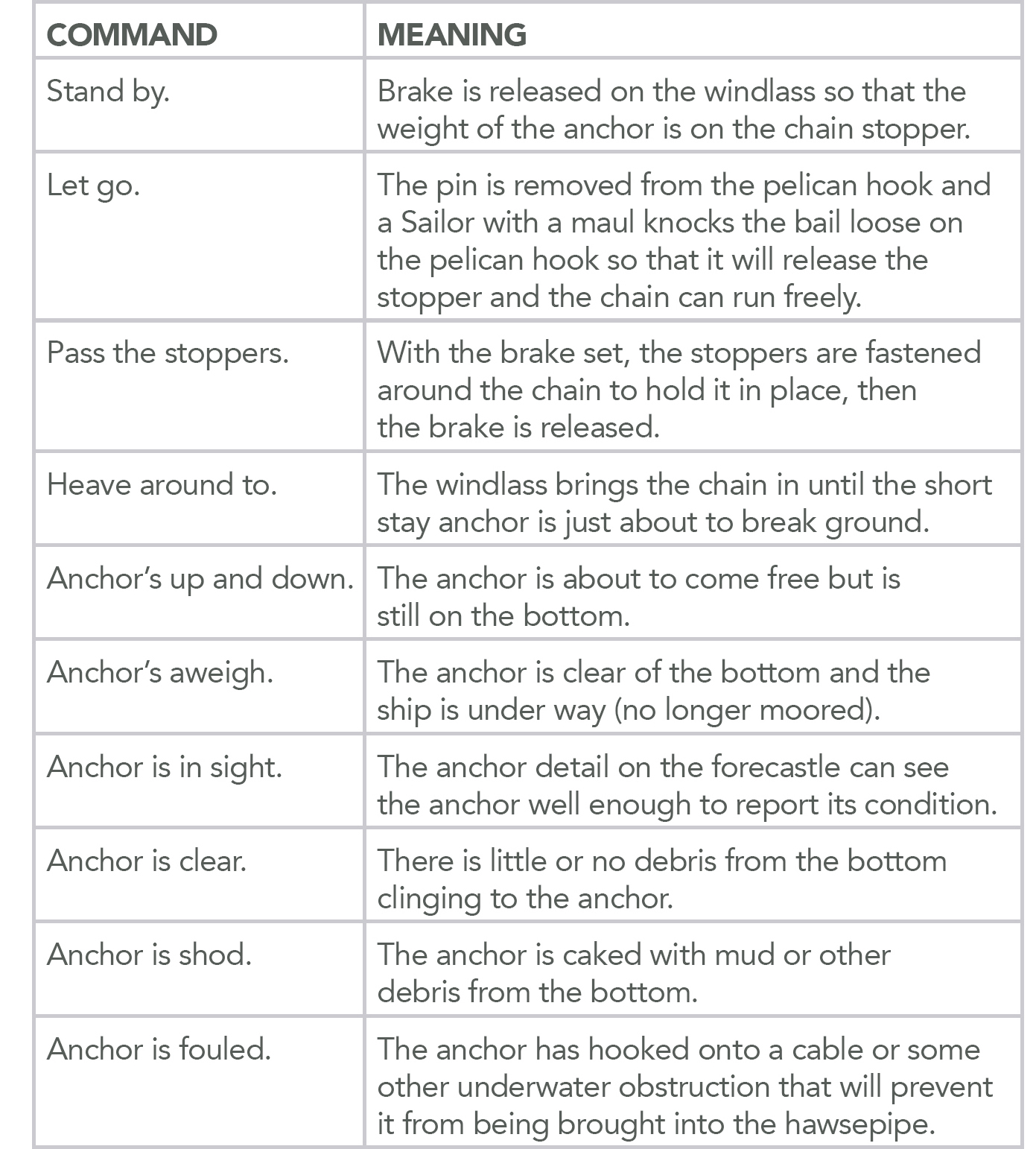

![]() TAB 12-D: Anchoring Commands

TAB 12-D: Anchoring Commands

![]()

![]() TAB 12-E: Blocks and Tackles

TAB 12-E: Blocks and Tackles

![]()

![]() TAB 12-F: Boat Customs and Etiquette

TAB 12-F: Boat Customs and Etiquette

12-A Mooring Line Configurations and Terms

Mooring lines are referred to by both numbers and by names. They are numbered starting with the forward-most one (number 1) and continuing aft in sequence. Mooring lines are named by a combination of their location, their use, and the direction in which they tend as they leave the ship.

Once a ship is moored to a pier or to another ship, it is important to prevent the ship from moving along (laterally) and to keep it from moving up and down (parallel to) the pier. Mooring lines are designed to prevent these two things. Lines that prevent ships from drifting away from the pier—in other words, that control lateral movement—are rigged perpendicular, or nearly so, to the pier and are called breast lines. Lines that prevent or minimize forward and aft movement—in other words, motion parallel to the pier—are rigged nearly parallel to the pier and are called spring lines.

The mooring configuration will differ depending upon the size of the vessel being moored and the surrounding conditions, such as tides, currents, and weather, but a standard six-line moor will illustrate most of what you need to know about mooring a ship to a pier. The first line farthest forward is called the bow line and runs through the bull-nose (chock on the very front of the ship) and then to the pier. The next line aft is numbered “2” and is called the after bow spring. This name is derived from the fact that it tends (goes) aft, is located in the forward half of the ship (hence the word “bow”), and is a spring line. In this case it prevents the forward motion of the ship. Moving aft along the ship’s main deck, the next line you would encounter would be the number three line, and it is called the forward bow spring. This, too, is a spring line because it keeps the ship from moving backward along the pier. The other parts of its name tell you it is located on the forward part of the ship (bow) and that it tends forward. The next two lines aft would be numbers four and five and they would be called the after quarter spring and the forward quarter spring, respectively. These lines are also spring lines and function the same as their counterparts on the bow. Because they are located on the after half of the ship, they are identified by the word “quarter” instead of “bow.” The final line in a standard six-line configuration is called the stern line. Like the bow line, this line is usually rigged as a breast line, meaning that it runs perpendicular (or nearly so) to the pier and is used to prevent lateral (in and out) movement of the ship in relation to the pier. Larger ships will, of course, rig more lines to secure the ship more effectively to the pier or another ship. Those rigged in the middle (amidships) of the ship are called waist lines. So an extra line rigged amidships to keep the ship snug to the pier, for example, would be called a “waist breast line.” If more lines are rigged, they still follow the rule of numbering from forward, so that the last line aft on a ship moored with eleven lines would be numbered “11.”

Once the ship is settled into her berth and all mooring lines have been rigged, they are usually doubled up. This is a somewhat misleading term because the way doubling up is accomplished results in three lines (actually parts of the same line) going from the ship to the pier instead of just one at each location.

![[12-A-1] A six-line moor. Note the fenders used to keep the ship from rubbing against the pier.](../images/f0596-01.jpg)

[12-A-1] A six-line moor. Note the fenders used to keep the ship from rubbing against the pier.

![[12-A-2] Doubling up](../images/f0596-02.jpg)

During the process of mooring a vessel to a pier or to another ship, it is vital that the conning officer be able to communicate efficiently with the line handlers. To make sure there is no confusion, commands that are commonly used in mooring operations have been standardized. This system can only be efficient if both the conning officer and the line handlers know what the various commands are and what they mean. Below are some examples of the standard commands used and what they mean.

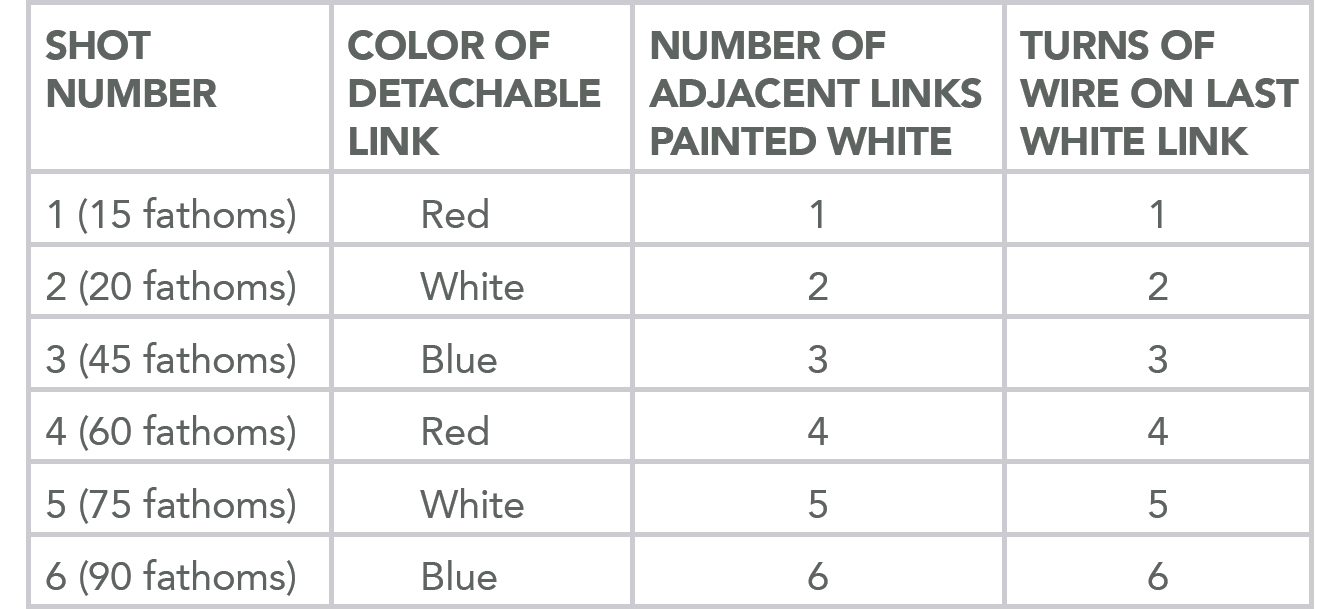

12-C Anchor Chain Identification System

A special color-coding system is used to identify the various shots so that when the ship is anchored, you can tell, just by looking at visible chain on deck, how much chain is out and underwater.

Each of the detachable links that marks the beginning of another shot of chain is painted either red, white, or blue. The links on either side are painted white (the number of links corresponding to the number of shots), and pieces of wire are also twisted onto the last white link to further aid in identification (the latter is useful in the dark when you cannot see the links clearly but can feel the turns of wire). Every link in the last shot of chain is painted red and every link in the next-to-last shot is painted yellow. This will give you warning that you are almost out of chain.

In the Navy, a block is essentially what civilians call “pulleys.” When blocks are combined with lines, they can be used to change the direction of an applied force (such as allowing you to pull down in order to lift something up) or, even better, they can be used to provide a significant mechanical advantage (which translates to “less work”). These combinations of blocks and lines are called tackles.

The simplest tackle is called a single whip and is made by running one line that has been attached to something (such as the end of a boom) through one block. This tackle gives you no mechanical advantage and is used solely to cause a change of direction in the force applied; for example, it allows you to lift a load straight up while you are pulling downward.

For obvious reasons, most tackles are rigged to achieve a mechanical advantage. The simplest tackle that provides this advantage is called a runner. Like the single whip, it uses only one line and one block, but by attaching the load to the block itself and allowing the block to move instead of attaching it to something, you gain a 2:1 mechanical advantage. (Note: In all cases described here, there is a certain amount of work lost because of friction, but the mechanical advantages gained are close enough for us to approximate them for simplicity.) That means that you will be able to lift a 120-pound load by using only 60 pounds of actual force—your load will seem only half as heavy as it actually is.

If you think about it, you can see that a runner would not be a very easy tackle to use because it is difficult to control, so a more common way to gain the same 2:1 advantage is to use two blocks (one moving and the other fixed) in a rig we call a gun tackle.

You have probably noticed that some blocks have more than one sheave (the “wheels” inside the block). Using a block with one sheave, combined with a block that has only two, we came up with a new rig called a luff tackle. This rig gives you a 3:1 mechanical advantage, which means your 120-pound load can now be lifted with only 40 pounds of force (it seems to weigh only one-third as much now).

Taking it another step, two blocks with two sheaves each can be rigged into a tackle we call a twofold. As you might have guessed, this rig provides an advantage of 4:1, meaning that you need only apply 30 pounds of force to lift your 120-pound load.

You may have noticed a pattern here that will help you to determine the theoretical mechanical advantage of a rig without having to come back to this book to look it up. If you look at the number of lines that are going in and out of the moving (not the fixed) block, it will tell you the mechanical advantage. For example, look at both the runner and the gun tackle. The number of lines running in and out of the moving block is two. This means the mechanical advantage is 2:1. The number of lines running in and out of the moving block on the twofold is four, so the mechanical advantage is 4:1.

Still more sheaves can be used in a two-block rig to gain even more advantage, but the friction factor begins to become sizable as you add more sheaves and lines so that the mechanical advantage is significantly degraded.

![[12-E] Blocks and tackles](../images/f0601-01.jpg)

12-F Boat Customs and Etiquette

Just as Navy ships adhere to certain customs and traditions, so do Navy boats.

Whenever Navy personnel board a boat, junior personnel embark first and seniors last. When the craft arrives at its destination, seniors will disembark first and juniors last. While embarked, seniors sit aft and juniors forward.

When under way, it is customary for boats to exchange salutes just as personnel and ships do. The coxswain (or boat officer, if embarked) will attend to all salutes, and the coxswain of the junior boat will initiate the salute and idle the boat’s engine during the exchange. The rest of the boat crew will stand at attention. Passengers will remain seated but come to seated attention (sit erect, looking straight ahead, and not talking).

FLAGS AND PENNANTS

The national ensign is displayed from Navy boats when:

• they are under way during daylight in a foreign port

• ships are dressed or full dressed

• they are alongside a foreign vessel

• an officer or official is embarked on an official occasion

• a uniformed flag or general officer, unit commander, commanding officer, or chief of staff is embarked in a boat of his or her command or in one assigned for his or her personal use

• when prescribed by the senior officer present

Since small boats are a part of a ship, they follow the motions of the parent ship regarding the half-masting of colors.

When an officer in command is embarked in a Navy boat, the boat displays from the bow the officer’s personal flag or command pennant—or, if not entitled to either, a commission pennant.

In a boat assigned to the personal use of a flag or general officer, unit commander, chief of staff, or commanding officer, or when a civil official is embarked, the following flagstaff insignia are fitted at the peak:

Spread eagle. For an official whose authorized salute is nineteen or more guns, such as Secretaries of the Navy, Army, Air Force, Chief of Naval Operations, and the Commandant of the Marine Corps.

Halberd. For a flag or general officer whose official salute is fewer than nineteen guns and for a civil official whose salute is eleven or more but fewer than nineteen guns (assistant secretaries of defense down to and including consuls general).

Ball. For an officer of the grade or relative grade of captain in the Navy and for a career minister, counselor, or first secretary of an embassy, legation, or consul.

Star. For an officer of the grade or relative grade of commander in the Navy.

Flat truck. For an officer below the grade or relative grade of commander in the Navy and for a civil official on an official visit for whom honors are not prescribed.

Note: The head of the spread eagle and the cutting edges of the halberd must face forward. The points of the star must face fore and aft.

![[12-F] Flagstaff insignia](../images/f0603-01.jpg)

BOAT MARKINGS

Admirals’ barges are marked with chrome stars on the bow, arranged as on the admiral’s flag. The official abbreviated title of the flag officer’s command appears on the stern in gold letters—CINCPACFLT (for Commander in Chief Pacific Fleet), for example.

On gigs assigned for the personal use of unit commanders not of flag rank, the insignia is a broad or burgee replica of the command pennant with squadron or division numbers superimposed. The official abbreviated title of the command, such as DESRON NINE, appears on the stern in gold letters.

The gig for a chief of staff not of flag rank is marked with the official abbreviated title of the command in chrome letters, with an arrow running through the letters. Other boats assigned for staff use have brass letters but no arrows.

Boats assigned to commanding officers of ships are called gigs and are marked on the bow with the ship type or name and with the ship’s hull number in chrome letters and numerals. There is a chrome arrow running fore and aft through the markings. On boats for officers who are not in command or serving as chiefs of staff, the arrow is omitted and letters are brass. The ship’s full name, abbreviated name, or initials may be used instead of the ship’s type designation. An assigned boat number is sometimes used instead of the ship’s hull number.

Other ship’s boats are marked on the bow either with the ship’s type and name or with her initials, followed by a dash and the boat number—for example, ENTERPRISE-1. These markings also appear on the stern of most boats. Letters and numbers are painted black. Numerals are painted as identifiers on miscellaneous small boats such as line-handling boats, punts, and wherries.