In the late 1950s and early 1960s, a small group of writers challenged long-accepted tenets of American literature with their iconoclastic approach to language and their angry assault on the conformity and conservatism of postwar society. As originators and role models of what came to be called the Beat Generation, they took aim at the hypocrisy and taboos of their time—particularly those involving sex, race, and class—in such provocative works as Jack Kerouac’s On the Road (1957), Allen Ginsberg’s “Howl” (1956), and William S. Burroughs’s Naked Lunch (1959).

Although they were a loosely knit collective rather than an organized movement, the Beats shared a deeply felt disappointment with the shallowness and acquisitiveness of American culture. This disaffection catalyzed their search for more artistically and spiritually attuned ways of thinking, living, and creating; frequently inflected by Eastern religion, these found expression in lifestyles and artworks that celebrated rootlessness, rebellion, introspection, and spontaneity. As their activities became more widely known, the Beats were imitated by other restive youths and scorned by mainstream voices that found nothing to admire in a scruffy subculture steeped in sex, drugs, and metaphysics. But such attacks only added to the Beats’ prominence, allowing them to flummox stereotypes—as when Kerouac said that he rejected “mutiny” and “insurrection,” standing instead for “order, tenderness and piety”—and making them a hotly contested symbol in the era’s culture wars. Kerouac, Ginsberg, and Burroughs were the most famous Beat writers, followed by the poets Gregory Corso, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Gary Snyder, and Diane di Prima, the hipsters Neal Cassady and Carolyn Cassady, and others less widely known. The places they lived in and wrote about ranged from Greenwich Village and San Francisco to Mexico, Western Europe, and North Africa; the subjects that fascinated them included drugs, music, sexuality, spirituality, and the urgency of finding what Ferlinghetti called “a new rebirth of wonder” in a jaded world.

Although they were predominantly a white male group, a modest number of African American writers and women can also be counted as members. Di Prima and Anne Waldman have exerted considerable influence on American letters through their energetic contributions to Beat poetry and poetics, earning recognition for their political activism and pedagogical innovation as well as literary excellence per se. Bob Kaufman was called the Original Bebop Man during the years when he enlivened San Francisco streets and coffeehouses with improvised poetry recitals, preferring not to record his verses on paper but to perform them wherever an audience might gather.

A more widely known African American Beat is Amiri Baraka, who changed his name from LeRoi Jones in 1967. After leaving military service in the middle 1950s he lived in Greenwich Village, became acquainted with Beat writers and other progressive literary figures, and founded Totem Press, which published Kerouac, Ginsberg, and di Prima, among others. He also edited the little magazine Kulchur and, in partnership with di Prima, The Floating Bear. Celebrated and controversial as a poet, playwright, publisher, polemicist, professor, and militant, Baraka left a distinctive imprint on the Beat years and beyond.

Members of the Beat Generation hoped that their radical rejection of consumerism, materialism, and regimentation would inspire others to purify their lives and souls as well. In this respect their values anticipate those of subsequent protest movements, such as the anti–Vietnam War campaigns that crested in the 1970s and the Occupy Wall Street demonstrations of 2011. In contrast with political protesters, however, the Beats urged the remaking of consciousness on a profoundly inward-looking basis, cultivating “the unspeakable visions of the individual,” in Kerouac’s vivid phrase. The idea was to revolutionize society by revolutionizing thought, not the other way around. The Beat writers and their disciples challenged received wisdom by cultivating radical ideas and drastic styles, fending off absorption into mainstream culture while inadvertently preparing ground for larger, more explosive social upheavals to come. Their influence waned as the Hippie movement arose in the middle 1960s, but their impact can still be felt in literature, cinema, music, theater, and the visual arts.

The Beats came of age in the World War II era, after living through the Great Depression, and the oldest of them, Burroughs and the poet Herbert Huncke, remembered the 1920s from their childhoods. Kerouac came into the world in 1922, and no fewer than three important Beat figures were born in the banner year of 1926: Ginsberg, Cassady, and the writer John Clellon Holmes, who was less a Beat leader than a chief observer and chronicler of their exploits. The youngest major Beats were Corso, born in 1930, Peter Orlovsky, born in 1933, and di Prima, born in 1934.

The most direct literary forebears of the Beats were the so-called Lost Generation writers, an informal gathering of Americans abroad, named after a comment by Gertrude Stein—“You are all a lost generation”—which Ernest Hemingway used as an epigraph in his first novel, The Sun Also Rises, published in 1926. The statement encapsulated the idea that World War I had prevented a whole generation of young men from having the civilizing experiences normal for people in their late teens and early twenties. Stumbling out of the most brutal conflict in history, they typically lacked direction, focus, and the sense of day-to-day purpose that their parents had (presumably) taken for granted. They were “lost” in an almost literal sense.

By the late 1920s, the Lost Generation label was being applied less to demobilized European fighters than to the American writers who had started circulating in and around the Left Bank of Paris, attracted by the city’s openness to high-modernist culture and—just as important—its inexpensive cost of living, thanks to favorable foreign-exchange rates. Paris also offered a refuge from the lingering influence of Victorian values in the United States, where Prohibition and prudishness still reigned. The Americans in Paris were a diverse lot, ranging from the macho Hemingway to the vulnerable F. Scott Fitzgerald; also present were such phenomenal avant-garde writers as Stein, T.S. Eliot, James Joyce, and Ezra Pound, as well as the adventurous publisher and bookseller Sylvia Beach. Lost they may have been, but they were amazingly productive too, changing cultural paradigms with their innovative prose and poetry, their support for new journals like Ford Madox Ford’s Transatlantic Review, and the conversations they shared while drinking away their nights (and often their days) in Montparnasse cafés.

The 1920s lost their roar when inflated stock-market prices abruptly crashed in 1929, bringing disastrous results to Americans and others as far away as Australia, where the next decade was dubbed the Dirty Thirties. Conditions in America grew even worse in 1931, when drought and dirt-blowing “black blizzards” turned much of the country’s southern and western agricultural land into a dust bowl plagued by poverty, sickness, and misery that persisted until 1939, when normal rain finally returned. Because of these awful circumstances and other factors, such as immigration from Europe and muckraking journalism, the 1930s sparked a good deal of progressive activity in the United States, including a fresh outpouring of labor-union solidarity. Popular culture was lively as well, from Hollywood studios where “talkies” drove out silent pictures to comic strips, where Superman made his debut in the illustrious company of Krazy Kat, Buck Rogers, and other antic characters.

Developments like these helped Americans keep a degree of optimism about the future. While some European and Asian countries turned to fascism and militarism for solutions, Americans hoped Franklin Delano Roosevelt, the new president elected in 1932, would pull things together with less extreme measures. Many viewed him as a closet socialist eager for government action on every front; but in reality he was a closet conservative, using government as a tool for restoring social equilibrium and saving the tarnished reputations of capitalism and democracy. What ultimately rescued America from the Depression was World War II, which opened the way for government interventions that could be praised as patriotic necessity rather than feared as creeping socialism. The war effort put countless people back to work, and victory boosted American morale to its highest level in decades.

America emerged from the war as the strongest power in the world. The economy boomed, powered by everything from the Marshall Plan abroad to the growth of credit-card spending at home. Developers promoted neat suburban homes as nesting places for right-thinking families. New technologies made life easier and more fun, at least for the middle class, and the press overflowed with predictions of how “harnessing the atom” would bring even greater things in days to come. The nation’s material well-being was not matched by feelings of psychological and spiritual health, however. The frequent use of terms like “rat race” and “lonely crowd” and “organization man” bespoke a nagging discomfort with side effects of the postwar economic boom. Conformity, explored in bestselling books like The Organization Man and The Man in the Grey Flannel Suit, was de rigueur. Conservatism was reflected by the two-time election of Republican war hero Dwight D. Eisenhower as U.S. president. Consumerism was fuelled by the Madison Avenue advertising industry and the skyrocketing power of commercial television. Consensus prevailed over pluralism, encouraging agreement on supposedly self-evident values while sweeping defects in the social order—often linked to inequalities of race, class, and gender—under the proverbial rug. Common sense usually meant believing what your friends and neighbors believed, not what intellectuals and “eggheads” said in fancy books. Cold-war paranoia spawned McCarthyism, anticommunist witch hunts, and a sense of brooding dread about Soviet plans to destroy the “free world” with nuclear weapons.

Uneasiness with these problems grew as the 1950s unfolded. The yawning gap between rich and poor refused to stop yawning. People borrowed too heavily and found themselves saddled with unnecessary debts. The manufacturing strategy of “planned obsolescence” kept consumers consuming by building limited life spans into commercial items from toasters to automobiles, which duly broke down just when they were starting to seem indispensable. Many suburbs were so standardized that it was hard to tell one carefully manicured house and lawn from another. Even the popular President Eisenhower could not build the interstate highway system he dreamed of without selling it as a new and improved way of moving America’s nuclear missiles to places where they might be needed when the Soviets attacked. The nation also harbored vicious racism, official in the southern states and subtler but still distressing in the northern ones.

Kerouac figured out much of this early in his career. His instinctive skepticism shows through in his first novel, The Town and the City, completed in 1949. In one sociologically sophisticated passage, a character mutely gives his small-town Massachusetts neighbors a series of sardonic warnings: “in God’s name, don’t fall out of line…. Look out for that budget. Responsibilities to meet, you know. Love your wife and kiddies.… Learn to accept the whip of your next in rank. Don’t revolt, whatever you do!” This crystallizes the Beats’ preference for dropping out of a corrupt system rather than passively participating in it. “As for me, ladies and gentlemen,” Kerouac’s character concludes, “I’m going to desert the sinking ship.”

Most people had no desire to jump ship, of course, and many pundits thought conformity was a benevolent force, easing the tensions and frictions of a complicated, fast-moving social order. But the idea of adjusting to society was troubling to thinkers who felt society should adjust to its citizens, not the other way around. The literary critic Maxwell Geismar wrote in 1954 that the arts of the Eisenhower era were swayed so strongly by social and intellectual conformity that superstition and ignorance had become the norm. Another skeptic was the sociologist William H. Whyte, who coined the word “groupthink” in a 1952 essay for Fortune magazine. He argued that while conformity has been around forever, modern conformity is rationalized enough to become a genuine philosophy, defining the typical person as a creature of the environment rather than an individual capable of self-determination.

These and other intellectuals wanted to warn modernized society against the dictatorship of “other-directed behavior,” to use David Riesman’s term. A particularly articulate warning came in 1956 from Robert Lindner, a psychoanalyst who refused to follow party lines or buy into conventional paradigms. His condemnation of “adjustment” read in part:

You must adjust … This is the motto inscribed on the walls of every nursery, and the processes that break the spirit are initiated there. In birth begins conformity.…

You must adjust … This is the legend inscribed in every schoolbook, the invisible message on every blackboard. Our schools have become vast factories for the manufacture of robots.…

You must adjust … This is the command etched above the door of every church, synagogue, cathedral, temple, and chapel.…

You must adjust … This is the slogan emblazoned on the banners of all political parties.…

You must adjust … This is the creed of the sciences that have sold themselves to the status quo, the prescription against perplexity, the placebo for anxiety. For psychiatry, psychology and the medical or social arts that depend from them have become devil’s advocates and sorcerers’ apprentices of conformity.…

Lindner’s warning was clear. According to contemporary cant, those who failed to “adjust” in the right ways might raise juvenile delinquents, see them flunk out of school, rub God the wrong way, vote for an unpatriotic party, and disappoint their psychoanalysts—a fearful litany of consequences for individuals who march too insistently to their own drummers.

Adjustment was pushed especially hard where matters of sex were concerned. Sexuality was heavily regulated by both law and custom during the 1950s. Homophobia was ubiquitous, although the word itself had not yet been invented, and heterosexuals were advised to “save themselves” for marriage. This meant in practice that young people plunged into marriage at earlier and earlier ages, only to become bored and restless in many cases, despite the lectures on “togetherness” they read in pop-psychology magazines. Female fashions had a neo-Victorian air, calling for padded bras, curve-enhancing girdles, and high-heeled shoes that turned women’s bodies into the equivalent of shielded citadels. While waiting for the “right person” to walk down the aisle with, one could watch family-worshiping TV shows on the order of Father Knows Best and Leave It to Beaver. Bolder sorts could peruse Alfred Kinsey’s hugely publicized reports on male and female sexuality, which appeared in 1948 and 1953, or read sex-oriented bestsellers such as Grace Metalious’s novel Peyton Place and Polly Adler’s memoir A House Is Not a Home, published in 1953 and 1956, respectively. Playboy debuted in 1953, raising the bar for sex in magazines; its first issue featured a nude shot of Marilyn Monroe, who was named America’s top female movie star in the same year.

But while sexy entertainment was widespread during the 1950s, it generally came with a look-but-don’t-touch message, manifesting the need for sex and the denial of sex that coexisted in the national ethos. The don’t-touch part of the message was particularly aimed at a segment of society that cares very much about sex: young people, of whom there were plenty, born in the postwar baby boom. As they grew into adolescence they encountered many older people eager to sell them the era’s popular products, from magazines, movies, and TV shows to the items advertised in them. And thus youth culture—now cultivated by marketers as a special domain with its own folkways, mores, opportunities, and obsessions—was born. This was something new under the American sun, and there was money to be made from it. The only thing missing was a counterculture group daring enough to call its bluff and expose its lies from within the youth culture itself. Enter the Beat Generation.

Like the Lost Generation before them, the Beats arose in the aftermath of a world war, and they saw the earlier group as a spiritual and aesthetic forerunner of their own circle, embodying a similar belief that forward-looking literature and art was an antidote to the nightmares of the past and the anxieties of the present. Also like the Lost Generation, the Beats had a romance with a foreign land, replacing cosmopolitan Paris with wild and woolly Mexico, a place that was steeped in history, rich in mythology, and sufficiently relaxed about drugs to be a sympathetic roosting place for what William S. Burroughs called “refugee hipsters.” The Beat chronicler John Clellon Holmes expressed the Lost Generation worldview beautifully when he said the generation that made the Roaring Twenties roar first appeared “in a roadster, laughing hysterically because nothing meant anything any more,” and went to Europe unsure about whether it wanted to find an orgiastic future or to escape from the Puritanism of the past. Its attitude was one of desperate frivolity, Holmes continued, and its pervading mood was a sense of loss.

One hears clear echoes of the Beats in this account. Yet there were contrasts between the groups as well. The Beats built their reputations mainly in their own country, for instance, and only a few of them shared the taste for extreme intricacy and fragmentation that Joyce, Pound, and Eliot cultivated in their work. More profoundly, as Holmes pointed out, the Lost Generation was occupied with the loss of faith, religious and otherwise, whereas many Beats were preoccupied with the need for it. Or as Kerouac put it in 1958, the Lost Generation built upon “ironic romantic negation” but the Beats were “sweating for affirmation,” seeking “absolute belief in a Divinity of Rapture.” Hence the religious overtones that swirl through such essential Beat texts as Ginsberg’s 1961 poem “Kaddish” and Kerouac’s 1965 novel Desolation Angels, among many others.

As inner-directed artists committed to the unspeakable visions of the individual, the Beats were wary of guides and gurus—even in the guru-mad 1960s, when (for one example out of dozens) the Beatles made the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi into a major celebrity. Discipleship is an important part of Buddhist tradition, however, and serious Buddhists like Kerouac, Ginsberg, and Snyder were devoted to the concept of the guru as Bodhisattva, less a leader or teacher than a spiritual reflection of the believer’s own Buddha nature. To them, seeking and cherishing the Bodhisattva, who is often found among the castoffs of materialistic society, was a way to pursue enlightenment in the wide world and simultaneously delve deeper into the sacredness of the self. Kerouac’s 1958 novel The Dharma Bums is the most extensive Beat treatment of this quest. Kerouac’s spiritual journey was a complicated one, beginning in Roman Catholicism, passing through a flirtation with atheism, shifting to an amalgam of Buddhism and Christianity, and culminating in a Roman Catholicism now strongly inflected by Buddhist teachings. These phases are reflected by turns, explicitly or implicitly, in nearly all of his books.

Ginsberg did not embrace a spiritual dimension in his poetry until the mid-1950s, but by the time “Howl” appeared in 1956 he was immersed in a search for expanded consciousness that took many forms. After involvement with Timothy Leary’s psychedelic scene in the early 1960s he felt the need for a more focused, productive study of the mind’s highest capabilities, and this is when he discovered Eastern thought. Kerouac had introduced him to Buddhism many years earlier, but he explored it more deeply while visiting India, where he spoke with the Dalai Lama and other sages. Returning to the United States after two years in Asia, Ginsberg used his new religious insights as a source of spiritual balance while plunging into the antiestablishment political struggles of the 1960s.

Ginsberg was much entangled with the material world during that tumultuous era, when his fame as poet, public reader, singer and musician, and activist soared. His attraction to Buddhism did not wane, however, and eventually his relationship with the Tibetan Buddhist teacher Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche revitalized his commitment and led him to take formal Buddhist vows. Trungpa was born in Tibet, where he built a reputation as an important teacher. He studied in India after the Chinese invasion of his homeland, read comparative religion at Oxford University, and emigrated to America at the urging of his American followers. In the United States he became a controversial figure, prone to sexual exploits and heavy drinking. (He died at age forty-seven of alcohol-related liver disease.) Yet his teachings were gentle, emphasizing deep meditation as a route to insight and awareness. His philosophy, like that of the Theravada Buddhist tradition, could be put into practice without belief in a specific higher power.

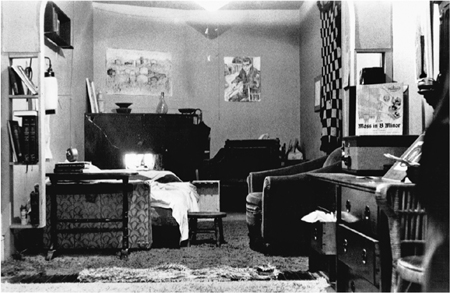

1. Ginsberg wrote Part I of “Howl” in the front room of the apartment he shared with Peter Orlovsky, his lover and fellow poet, at 1010 Montgomery Street, San Francisco, in the spring and summer of 1955.

It is not surprising that Ginsberg was attracted to Trungpa, who loved spontaneity and improvisation, disdained social convention, and wanted to write poetry, enlisting Ginsberg’s help in exchange for religious instruction. Like the Beat poet and performer Anne Waldman, another Trungpa student, Ginsberg found the Tibetan tradition of “crazy wisdom” completely in tune with his own rejection of “correct” cultural norms. Trungpa alienated many potential followers, however, including Kenneth Rexroth, the Beat writer and intellectual, who once remarked, “Many believe [he] has unquestionably done more harm to Buddhism in the United States than any man living.”

Be that as it may, Trungpa was an energetic entrepreneur. In 1973 he founded Vajradhatu, an umbrella organization for his North American activities. The following year—in Boulder, Colorado, where had set up headquarters—he established the Naropa Institute, which evolved into Naropa University, the country’s first accredited Buddhist university. Building on Naropa’s mandate to commingle Eastern and Western ideas, Ginsberg and Waldman founded the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics there in 1974, at Trungpa’s invitation. Ginsberg taught classes there every summer until he died, and Waldman is still affiliated with the school, which now comprises the university’s writing and poetics department and its summer writing program. In these respects at least, Trungpa’s legacy has been a productive one.

Another important Beat figure linked with a controversial guru was Philip Whalen, a San Francisco Renaissance poet who appears under various names in Kerouac novels. Whalen discovered Buddhism as a high school student and never looked back, becoming the most ardent Buddhist scholar in the Beat circle. In college he roomed with the future poet and environmentalist Gary Snyder, later following Snyder’s footsteps to Japan and living in that country from 1969 to 1971. Perhaps inspired by serving as an isolated fire lookout in the Pacific Northwest mountains—an experience Snyder and Kerouac also had—Whalen became a Zen monk in 1973 and was involved with the San Francisco Zen Center when Zentatsu Richard Baker was its abbot. Baker left the center in 1984, accused of having inappropriate sexual relationships with female students and unfairly exploiting the center’s successful business activities. Whalen thrived nevertheless, becoming chief monk at two American Buddhist centers before his death in 2002. He also taught at the Naropa Institute and published several books of Zen-inflected verse that have an enthusiastic following among discerning readers.

According to popular stereotypes, the 1950s were the most sexually repressed decade in modern times. This is partly true. The producers of the CBS television sitcom I Love Lucy (1951–1957) were not allowed to use the word “pregnant” in a script. Movies and TV shows had married couples sleeping in separate beds. Hollywood filmmaker Otto Preminger ran into censorship problems when a character said “virgin” in The Moon Is Blue (1953) and when another used heroin in The Man with the Golden Arm (1955). CBS instructed The Ed Sullivan Show (1948–1971) to display singer Elvis Presley only from the waist up after earlier appearances brought howls of protest over the sight of his gyrating hips.

Nonetheless, the 1950s had libidinal impulses as strong and plentiful as those of other decades. They were indirectly expressed in the public sphere, but they were impossible to miss. Hugh Hefner started a publishing revolution when his men’s magazine Playboy reached newsstands in 1953. The buxom Marilyn Monroe became a superstar, and second-tier blonde babes like Jayne Mansfield and Diana Dors immediately imitated her. Vladimir Nabokov’s scandalous Lolita reached the best-seller lists and the title of Metalious’s fornication-filled novel Peyton Place became a household phrase. People who had gasped at Alfred Kinsey’s report on Sexual Behavior in the Human Male in 1948 found even more surprises when Sexual Behavior in the Human Female appeared in 1953. Homosexuals are everywhere! People masturbate!

Sexual freedom was a given for most Beats, and Beat writers did not hesitate to pour their sex-related longings, fantasies, and adventures into their poems, novels, and stories. Beat sexuality did not become an open book for all to read, however, and authorities on the Beat Generation still debate questions related to it. One such question concerns the appropriate label—if any—for the sexuality of a Jack Kerouac or a Neal Cassady, who considered themselves heterosexual but had homosexual experiences. Cassady was such a bundle of raw, hungry nerves that departing from his usual heterosexual habits (in his affair with Ginsberg, for instance) probably struck him as more a vacation than a transgression. By contrast, some authorities claim that Kerouac was a profoundly repressed homosexual (bisexual would be more accurate) who used alcohol and drugs to lower his inhibitions for gay encounters, then used them again to ease anxiety and guilt.

As young men, Ginsberg and Burroughs were uneasy about their gay identities, and both tried more than once to be “cured” of homosexuality. Ginsberg had occasional female lovers, and Burroughs had a common-law wife and a son. But before long they came to terms with homosexuality and explored it fully in their writing. Burroughs also became a fan of the “orgone accumulator” invented by the maverick psychiatrist Wilhelm Reich, who believed that a box lined with the proper material can collect a life force called orgone energy. A person can absorb this energy by resting in the box, Reich taught, and then discharge it through sexual activity, achieving physical and psychological health while having a walloping good time.

Kerouac was interested in Reich’s ideas too. He describes Burroughs’s enthusiasm for orgone boxes in On the Road, when Sal and Dean visit the Burroughs character (Old Bull Lee) at his Louisiana home, where he has built one. At the end of his “Essentials of Spontaneous Prose,” moreover, Kerouac advises modern writers to “write excitedly, swiftly, with writing-or-typing-cramps, in accordance (as from center to periphery) with laws of orgasm, Reich’s ‘beclouding of consciousness.’ Come from within, out—to relaxed and said.”

More controversially, Ginsberg had a higher tolerance for adult-child sexuality than the vast majority of Americans in his day or ours. He argued that prepubescent children “don’t have to be protected from big hairy you and me, they’ll get used to our lovemaking in 2 days,” and in the 1980s he joined the North American Man Boy Love Association, citing defense of free speech and civil liberties as his reason. He made it clear, however, that he did not practice such sexuality; that he regarded NAMBLA as “a discussion society not a sex club”; and that he respected “those who want to fix a general law to prevent abuse of minors.” Here as in other contentious areas, Ginsberg pursued his activism as an artist and intellectual who sought not to overpower but to persuade.

In the end, it is impossible to pin down a specifically Beat sexuality. Look at The Dharma Bums, for instance, and you find the Gary Snyder character (Japhy Ryder) doing yabyum with his friends—being naked together in body and soul—while the Kerouac character (Ray Smith) declines the sensual fun, choosing to continue the celibacy he hopes will cleanse him of attachment to the world. The Beat Generation has room for every kind of sexuality, including none.

There was a period in the 1960s when a litmus test for drug-culture common sense was to compare Allen Ginsberg with Timothy Leary, asking which radical sage had the better answer to the question of how best to expand one’s consciousness.

Leary, a Harvard University psychology professor until 1963 and a freelance guru after that, was a charismatic figure who altered the era’s popular culture with his contention that hallucinogenic drugs are the ideal instrument for turning on, tuning in, and dropping out of the bourgeois rat race. This led him to bestow his magic substances on one and all, with tragic results as well as happy ones. Ginsberg saw hallucinogens as an exciting and efficient way of achieving what Rimbaud called the systematic derangement of the senses, but he eventually found it more exciting and efficient to cultivate the mind’s transcendent powers without artificial aids. His growing commitment to Buddhism was one outcome of this reasoning.

Drug experimentation was a way for Beats to challenge square society’s joy-killing values while getting powerfully high in the process. Historically, most Beats were into “body” drugs before psychedelic “mind” drugs came their way. Heroin, morphine, and Benzedrine were the most popular, and Benzedrine was easy to obtain by breaking open a plastic tube of nasal inhalant and swallowing the solution-drenched cotton inside. Body drugs are addictive, of course, and Burroughs was the Beat with the most famous monkey on his back. His dependency may have started at age fourteen, when he was injured in a chemistry-set mishap and given an adult dose of morphine at a hospital. A few years later, he sold his new friend Herbert Huncke some stolen Syrettes of morphine tartrate and decided to try one before completing the transaction; soon thereafter he became addicted to heroin.

Burroughs wrote about the hard-drug scene in Junkie, and by the time of Naked Lunch he was using addiction as a potent metaphor for issues of control and rebellion. He looked into mind-altering drugs as well, visiting South America during the early 1950s in search of ayahuasca, also called yagé, which was said to give its users access to telepathic powers. Ginsberg made a similar quest about a decade later. They collaborated on The Yagé Letters, published by City Lights in 1963, although Burroughs apparently wrote most of the slim volume. Burroughs kicked his heroin habit for many years, then took it up again in the late 1970s, when he was hanging out with New York celebrities. His desire to kick it again was a chief reason for his move to Lawrence, Kansas, in 1981. None of this kept him from living a long, full life.

Kerouac’s drug of choice, alcohol, worked for him (all too well) as a soother of mind and body. In addition to its narcotic effects, Kerouac valued it as a route to the nonattachment—which he saw as a sort of spiritualized oblivion—called for by his Buddhist beliefs. He experimented with other drugs as well, and in a poem like “Morphine” he sees “high” as both a physical and a spiritual state: “Nothing like a shot of junk for sheer / Heavenly contact.” For him, spirits took many forms and wine was junk at its most sublime. Alcohol killed him, but alcohol also brought him alive.

The Beat Generation has been a major force for good, disputing the social rules of a sadly straitlaced era and opening up enormous new areas of thought and expression. Its innovations were fueled by its discontents. Kerouac was outraged by the alienation and mechanization of industrialized society; Burroughs waged war on cultural control systems; Ginsberg felt the world’s problems arose from national powers imposing a uniform consciousness on the masses.

Inevitably, however, the Beat movement also had negative aspects. While its emphasis on sexual freedom was liberating and exhilarating, its implicit endorsement of anything-goes morality ushered in irresponsible and destructive patterns; even the young Kerouac portrayed the womanizing ways of Neal Cassady, the Dean Moriarty of On the Road, as a hazard and aggravation for all concerned. Similar things can be said regarding Beat drug and alcohol abuse, although the real problems started when the Hippies transformed dope from a special experience for the enlightened to a diversion for anyone who could afford a fix, a bag, or a snort.

Also problematic in some respects was the Beat emphasis on inner revolution rather than political activism. Key figures like Ginsberg and Ferlinghetti were outspoken political thinkers, to be sure, and Burroughs’s hatred of conformity and consensus makes his best books outstanding manifestos for radical change. Yet exploring the unspeakable visions of the individual allowed Beats to avoid the necessity for collective action. At times these ardent nonconformists sounded eerily like the unenlightened society they were nonconforming to.

This was especially true of Kerouac, who became more and more conservative as he aged; eventually his nonviolence seemed paranoid, his anticommunism seemed reactionary, and his irreverence seemed like bigotry. When his friends Ginsberg and Carl Solomon criticized aspects of two early novels, he saw himself as an innocent L’il Abner among unfeeling Jewish businessmen. By the early 1960s he had dumped countless anti-Semitic epithets on Ginsberg, and in 1961 he agreed with his mother—in Ginsberg’s presence—that Jews shouldn’t still be complaining about the Holocaust, and that Adolf Hitler should have finished what he started.

If there is any excuse for this besides alcoholism and depression, it is that Kerouac increasingly saw himself as a miserable sinner surrounded by a miserably sinful world, in which self-improvement is doomed along with all other human enterprises save the soul’s quest for divine grace in the afterlife. For him, social ills were not problems to be solved but sins to be expiated by penance and atonement. Alcoholism and depression were the forms this penance took for him.

Ginsberg cultivated political awareness throughout his life, and most of his views were tolerant to a fault. Yet he did not shy away from pushing people’s buttons, even in areas related to his own Jewish heritage. “The trouble with the Israelis is that they are Jewish,” he remarked in the early 1960s, “they were hypnotized by the Nazis and all other racist magic hypnotists of previous eras. Astonishing mirror image resemblance between Nazi theory of racial superiority and Jewish hang-up as chosen race.… Any fixed static categorized image of the Self is a big goof.”

Burroughs was such a corrosive writer that he seems more misanthropic—prejudiced against humanity in general—than biased against any particular group. “Take a look at the human artifact,” he writes in The Adding Machine. “What is wrong with it? Just about everything.” That said, even his close associate Brion Gysin objected to an anti-Semitic tone in Cities of the Red Night. Burroughs responded that the phrases expressed his characters, not himself; yet when replying to Gysin he took the opportunity to recap some “Jew jokes” from earlier works. With regard to gender, Burroughs acknowledged his reputation as a misogynist, and most of his fiction is so dominated by males that it is hard to imagine him taking a serious, empathetic, or politically and morally progressive attitude toward women. Readers are free to decide whether his general disdain for the human species gets him off the hook, or is just an excuse for old-fashioned male chauvinist piggery. “Women may well be a biological mistake.… But so is almost everything else I see around here,” he once opined. Given the state of world affairs, the second half of that statement is hard to argue with. The first half is another story.