The Beats were an informal group, to the extent that they were a group at all. They were not “doing at all the same thing, either in writing or in outlook,” Burroughs said. “You couldn’t really find four writers more different, more distinctive. It’s simply a matter of juxtaposition rather than any actual association of literary styles or overall objectives.” Burroughs added, however, that they did have group importance on sociological and ideological levels, since they broke down all manner of social barriers and encouraged radically open-minded communication among peoples around the world. The public certainly identified the Beats as a group, and none of the Beats appeared to mind.

Nor was there much disagreement on who the core members were: Kerouac, fiercely committed to the spontaneous writing that he pioneered; Ginsberg, a member of the New American Poetry avant-garde inspired by everything from nineteenth-century verse to late-night radio patter; and Burroughs, a storyteller with a schizoid style and a hearty appetite for pleasures of the flesh. Underlying their merry pranks and zany eccentricities was a passionate search for what Ginsberg called “eyeball kicks,” the jolts of cosmic energy that divide everyday entertainments from visionary art.

Jack Kerouac was restless from the start. He was born in Lowell, Massachusetts, to French-Canadian-American parents who named him Jean Louis Kirouac, as the family name was spelled on his baptismal certificate. He was called Ti-Jean (Little John) as a child, and until age six he spoke Joual, a French-Canadian dialect for which he retained lifelong affection. He grew up in Lowell, a factory town on the skids, in a family plagued with problems. Some were financial, growing worse when his father’s printing business went downhill; others were existential, hitting Kerouac especially hard when one of his three older brothers died of rheumatic fever at age nine. The boy’s name was Gerard, and Kerouac never stopped remembering, idealizing, and literally praying to him, since Gerard appeared to have a vision of the Virgin Mary not long before his death. Jack took this as a sign that his late brother had become a saint.

Kerouac loved Lowell despite such ordeals, and he often returned there in his fiction—sometimes realistically, as in The Town and the City, other times deliriously, as in Doctor Sax: Faust Part Three. But he had no intention of remaining there for life, as many friends and family members did. He parlayed his status as a high-school football star into scholarship offers from several colleges, and settled on Columbia University because he was eager to try living in New York, the biggest big city of them all. (Going to Columbia meant spending a preparatory year at the Horace Mann School, also in New York, so he moved there in autumn of 1939.) But he found Columbia more like a psychological prison than an intellectual haven, and his football career declined because of a leg injury and a steadily declining relationship with his coach. Before long he was a dropout, living on the Upper West Side of Manhattan and making many friends, some of whom—Burroughs, Ginsberg, Cassady, Huncke, Holmes—helped shape his future, as he did theirs.

Military service beckoned when America entered the war. Legend has it that Kerouac joined the army, the marines, the coast guard, and the navy on a single alcohol-soaked night in 1943. In fact, he joined the merchant marine in 1942, and his motives were more personal than political. When wartime arrives in The Town and the City, his first novel, the autobiographical character Peter Martin hopes that shipboard service will be the first “great step” in the life he hopes to have. Yet, the narrator says, “he never thought of this in terms of war, but in terms of the great gray sea that was going to become the stage of his soul.… Mighty world events meant virtually nothing to him, they were not real enough, and he was certain that his wonderful joyous visions of super-spiritual existence and great poetry were ‘realer than all.’”

Such hopes notwithstanding, Kerouac lasted long enough in the merchant marine to take exactly one voyage, then enlisted in the navy in late 1942. Once there he started complaining of headaches, getting onto the sick list after eight days on active duty. At this point he drew a diagnosis of schizophrenia (then called dementia praecox) and spent several weeks in naval hospitals, although he rejected the diagnosis, stating that while he did see vivid mental images at times—a trait that strongly influenced his writing in time to come—he did not hear “voices” or suffer from other symptoms of the disease. Phrases like “Spree drinker” and “tends to brood a good deal” show up in his records. Without any particular training, wrote one psychiatrist, the patient was an enthusiastic novel writer who saw, strangely enough, “nothing unusual in this activity.” Another quoted Kerouac’s father, who called his son “seclusive [sic], stubborn, headstrong, resentful of authority and advice,” and said the young man had “been ‘boiling’ for a long time.” Kerouac left the military in June of 1943, a few months after he’d joined up. The official record stated: “Unsuitability for the Naval Service with Indifferent Discharge.”

Back in New York, Kerouac made the acquaintance of Burroughs, Ginsberg, and Huncke, and in 1944 he and Edie Parker, a classmate at Columbia, got married. A little later he met Neal Cassady, one of the most genuinely momentous events in Beat history. Cassady hailed from Denver, and a bus trip to visit him there was an early installment in the saga of compulsive traveling that stands at the center of Kerouac’s life and legend. Destinations he visited between 1947 and 1957 included San Francisco, the Sierra Nevadas, North Carolina, Washington State, Mexico City, England, France, and Morocco. In the course of these travels he married his second wife, became more serious about Buddhism, helped to organize and type Naked Lunch for Burroughs in Tangier, Morocco, and wrote almost all of his important works. Kerouac’s output during the 1950s averaged two books every twelve months, according to his friend John Clellon Holmes, who reckoned that American literature had never seen such a burst of creativity except during the four years when William Faulkner wrote four of his greatest novels.

Kerouac’s first published book was The Town and the City, which he wrote between 1946 and 1949 in the manner used by authors for centuries: write, revise, write, revise. Soon he would criticize and reject this methodology, but so far he hadn’t seriously questioned it. Harcourt Brace published The Town and the City in 1950, and Kerouac earned a modest amount of attention as a promising new writer, only to find himself back in obscurity a year later. The market was slim for long, earnest books chiefly influenced by Thomas Wolfe and filled with laments about the contradictions of modern American life.

In 1950 Kerouac also married Joan Haverty, the widow of his friend Bill Cannastra, who had recently died a grotesque death during an attempted prank, climbing out a subway-car window just as the train entered a tunnel. Haverty left Kerouac in short order, realizing that no wife could compete with his strong attachment to his mother, but she let him move into her apartment to continue work on his new novel, which he had started in 1948. Tentatively titled On the Road, it was based on extensive journals containing experiences and impressions he had accumulated during his travels. By the beginning of 1950 he had written many pages of On the Road and was unhappy with all of them.

Casting about for ways to reinvent and invigorate his style, Kerouac went back to a pair of remarkable letters he had received from Cassady, the Dean Moriarty character in the new novel. Written in 1947 and 1950, the Great Sex Letter and especially the Joan Anderson Letter, as they came to be called, had a manic exuberance and go-for-broke unruliness that Kerouac called “kickwriting.” How could one create such wholly spontaneous, radically in-the-moment writing on a regular basis? The answer came to him as he listened to the free-flowing riffs of alto sax virtuoso Lee Konitz one evening in 1951. The secret was to emulate the endlessly inventive improvisations of his favorite jazz musicians.

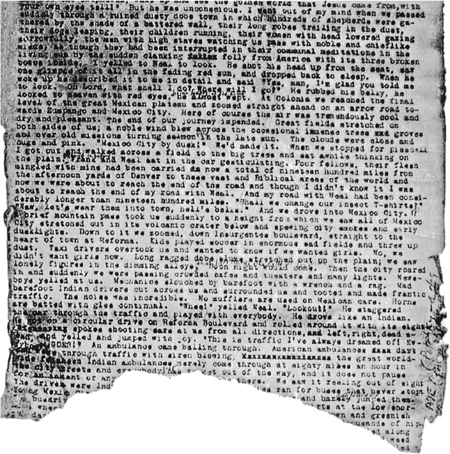

Kerouac restarted On the Road in line with his new idea. Since spontaneity was the key, he taped sheets of drawing paper end to end so he could feed them into his typewriter as a single long scroll, eliminating the need to pause each time the paper needed changing. Considered in musical terms, Kerouac was moving from a concert-orchestra model, where pages are turned on the music stand as the piece proceeds, toward a progressive-jazz model, where nothing need interrupt the creative flow except the biological imperative of breathing. Kerouac also decided to disregard such fundamentals of Writing 101 as punctuation and paragraphing; he treated words less as links in a syntactic chain than as notes in a melodic stream, moving in a seamless progression guided only by the author’s instincts and intuitions during the moment-to-moment creative act. The result was an unprecedented feat of “spontaneous bop prosody,” in Ginsberg’s felicitous phrase, running to almost 120 feet of breathlessly composed single-spaced text.

Like its style, the novel’s content also breaks the rules. Its subject is Kerouac’s travels through America with Cassady, his closest and hippest friend. But there is no story in a conventional sense. Instead there are actions, descriptions, and impressions ordered by the pulsating energy of two young men who rarely manage to sit still, love most of the things they see, hate the rest of them, and treat indifference with contempt. Their shades of feeling are expressed in vivid, muscular prose, committed to paper in about three weeks, thanks to Kerouac’s lightning-quick typing speed and capacity for working day after day with little rest as long as steady supplies of coffee were available.

4. Jack Kerouac typed On the Road on a scroll that was almost 120 feet long. The bottom end of the scroll is ragged, and Kerouac wrote a penciled note in the margin stating that Potchky, a cocker spaniel owned by his friend Lucien Carr, chewed up the last inches when no one was looking. Some observers speculate that Kerouac ripped it off himself, however, because he was dissatisfied with the original ending.

On the Road recounts four trips across the American continent. In the first, Kerouac stand-in Sal Paradise starts hitchhiking from New York to Denver but winds up taking a bus as far as Chicago and thumbing again from there. After adventures in Denver with Dean Moriarty and Carlo Marx, the Cassady and Ginsberg characters, he heads for San Francisco, where another old pal is living. But he soon races away from the unappetizing life he finds there, landing in Southern California, where he does manual labor with a Mexican girl he met on a southbound bus. Then he returns to New York.

The second trip starts in Virginia, where Dean unexpectedly arrives with his girlfriend and a guy named Ed Dunkel, who is supposed to rendezvous with his wife in New Orleans, where Old Bull Lee, the Burroughs character, now lives. The four of them drive north to New Jersey and New York, then south to New Orleans, then west to San Francisco to see Dean’s other girl, who is pregnant. Dean decides to stay with his San Francisco woman, and Sal boards a bus to New York.

Trip three begins when Sal heads for Denver and then San Francisco, in search of Dean again. After some unpleasantness with women, the two men hitchhike to Denver and make a high-speed drive to Chicago in just seventeen hours. Then they go back to New York, but not for long. After his first novel gets published, Sal goes to Denver and hooks up with Dean, whereupon they drive to a Mexican village for amusement with hookers and dope. Dean zips off to New York when Sal gets sick, and Sal returns when he is on his feet again. The story ends on a bittersweet note: Sal waves goodbye to Dean in New York, knowing his friend has irresponsible and even disloyal sides, yet realizing Dean has forever changed the ways he, Sal, looks at life.

For generations born after the Beat one, it is hard to imagine how much fascination the freedom of the open road once held. In the years immediately after World War II, the United States was hardly the untamed land (untamed by European exploiters, that is) of the old colonial and pioneer periods. But it was still vast and varied enough for adventurous spirits to be exhilarated by the prospect of traveling through it. The nation has grown larger since Kerouac packed away his hitchhiking shoes, with two additional states, Alaska and Hawaii, joining the union in 1959. Still, the country seems less exotic today than it did in the 1940s and 1950s, when farms and small towns dominated the continent and the interstate highway system (about 41,000 miles of roadway) was in its infancy.

In short, American geography had mystique in those days. Television, just starting to flex its commercial muscles, had not yet homogenized the nation by imposing sameness on everything it showed. Going to a new place could mean hearing accents, seeing clothes, sampling foods, and encountering folkways one had never experienced before. Adding to travel’s appeal for Kerouac was the concept of fellaheen, picked up from Oswald Spengler’s book The Decline of the West, which Burroughs brought to his attention in 1944. The word “fellaheen,” which Kerouac spelled “fellahin,” comes from “fellah,” an agricultural worker or peasant in an Arabic-speaking country. Kerouac used the term broadly; in On the Road, for instance, narrator Sal Paradise calls fellaheen “the essential strain of the basic primitive, wailing humanity” and also “the source of mankind and the fathers of it.” Kerouac regarded fellaheen as another version of the meek who will inherit the earth; as Sal hypothesizes, “when destruction comes to the world of ‘history’ and the Apocalypse of the Fellahin returns once more as so many times before, people will still stare with the same eyes from the caves of Mexico as well as from the caves of Bali, where it all began and where Adam was suckled and taught to know.” The secret of their resilience is an ability to live in the here and now, not the might-be or could-be of abstract cultural thinking.

Kerouac’s views about this were naïve—his own generalizations about fellaheen, for example, tend to be lacking in concrete detail—and sometimes his notions are strikingly out of touch with reality, as in the part of On the Road where Sal takes a walk in the African American district of Denver:

… feeling that the best the white world had offered was not enough ecstasy for me, not enough life, joy, kicks, darkness, music, not enough night.… I wished I were a Denver Mexican, or even a poor overworked Jap, anything but what I was so drearily.… I was only myself … wishing I could exchange worlds with the happy, true-hearted, ecstatic Negroes of America.

You want to shake Kerouac and tell him to face facts. Life in a metropolitan “colored section” of the late 1940s was likely to be poor, hard, and violent, not a gentle reverie filled with joy and kicks. Kerouac had every right to feel let down by the unkept promises of the American dream, but his dreamy view of urban fellaheen is as inaccurate in its particulars as it is ineffectual in raising Sal’s spirits.

Kerouac was naïve enough to wish away aspects of fellaheen reality that did not comport with his desires and fantasies, but he was sensitive enough to be psychologically stunned by a growing realization that no human imagination can ultimately come to terms with the infinite number of ills and evils in the world. Reading letters that Kerouac sent him from the west coast of Mexico, the slums of Los Angeles, lumber towns in Washington, rusty tankers at sea, and God knows where else, John Clellon Holmes was reminded of a drowning person whose struggles make a dire situation worse, a man who was “gradually sinking out of sight, down into the darks of life and Self, below ‘literature,’ beyond the range of its timid firelight.” Yet during his travails Kerouac kept on communicating, traveling more deeply into himself as he roamed the endless stretches of the American road. The form that best echoed his experiences, he wrote in a 1952 letter, was “wild form, man, wild form.… I have an irrational lust to set down everything I know … at this time in my life I’m making myself sick to find the wild form that can grow with my wild heart.”

Everything has a flip side, however, and Kerouac’s romance with the road is no exception. The romance grew partly from his profound yen for adventure and novelty. But it also stemmed from his discontent with American life as it is usually lived, which failed to give him equivalents for the comfort of his childhood home, his early religious experiences, and his origins in a modestly populated New England city, where he had grown up delicately poised between urban and small-town lifestyles—both of which, contradictory as they were, kept on tempting him.

As soon as the Beat Generation became a cultural phenomenon, moreover, people started seeing Kerouac as a Beat kingpin straight out of his own pages—forgetting that while On the Road is rooted in reality, it is a novel and not a memoir, autobiography, or confession. One of the reasons why Kerouac hitchhiked so much is that he hated to drive; and this didn’t solve the problem, since he also hated hitchhiking, feeling an “essential shame” when begging for rides. Having sore feet and empty pockets didn’t help, either. Holmes recalled that Kerouac always dreaded the prospect of being stranded in some cold, inhospitable place when he embarked on a hitchhiking trip.

As for Kerouac’s supposed love affair with automobiles, Holmes personally saw him “crouching on the floor of a car, in a panic, during a drunken, six-hour dash from New York to Provincetown.” The king of the Beats was human, all too human, like the rest of us.

It is interesting to observe that Kerouac’s last big traveling year, 1957, was the year when On the Road was published. In 1958 he bought a house for himself and his mother in Northport, Long Island, and started oscillating between there and Florida, always with his beloved parent, Gabrielle “Mémêre” Kerouac, in tow. The wanderer still had his wanderlust, but now it took a very different form, and by the time he finished Desolation Angels in 1961 he was ready to give traveling up for good. In that novel he visits Tangier, where he says to himself:

Jack, this is the end of your world travel—Go home—Make a home in America—Tho this be that, and that be this, it’s not for you—The holy little old roof cats of silly old home town are crying for you, Ti Jean—These fellas don’t understand you.

And he meant it. He made a short trip to France in summer 1965 and drew material for Satori in Paris from it; but apart from that he stuck mainly to the East Coast of the United States in his later years, moving from Florida to Cape Cod in 1966 and back to Lowell the following year. Although alcohol and illness had taken a large toll on him by then, he managed a trip to Europe with his brothers-in-law in 1968 (he had married his third wife, Stella Sampas, in 1966), and shortly thereafter he made a final move to St. Petersburg, Florida, where he died.

Kerouac’s embrace of spontaneous composition influenced many writers, including other Beats, who shared his conviction that only a revolution in writing could counter the conformity and consensus that had midcentury America in a stranglehold. Ginsberg hailed improvisation as a privileged means of access to “immediate flash material from the mind,” and Burroughs produced quasi-spontaneous effects by cutting, pasting, and folding preexisting texts in a semirandom manner.

Half a dozen years elapsed before Viking Press published On the Road in 1957, and reception of the book was mixed. The most important positive review came from Gilbert Millstein, who welcomed it in the New York Times as a “major novel” and an “authentic work of art.” The most famous put-down came from author Truman Capote, who sniffed, “It is not writing. It is only typing.” But neither the delay in publication nor the scorn of unsympathetic critics diminished Kerouac’s enthusiasm for spontaneous writing, or for the broader philosophy of “first thought best thought,” holding that off-the-cuff intuition is the best route to creative excellence. Insisting that revision is the enemy of art, he took to criticizing Ginsberg for correcting simple typos and slips of the finger in his manuscripts. In a manifesto called “Essentials of Spontaneous Prose,” Kerouac called for “blowing (as per jazz musician) on subject of image” and “following free deviation (association) of mind into limitless blow-on-subject seas of thought,” and another statement, “Belief & Technique for Modern Prose,” contains advice like “Struggle to sketch the flow that already exists intact in mind” and “Something that you feel will find its own form.” While jazz improvisation remained his primary model, he also saw himself as the verbal equivalent of a visual artist, using words to capture and convey the images that swarmed so plenteously in his mind’s eye. In addition to facilitating the aesthetic results he prized, Kerouac felt that “bop-trance composition” was a guarantor of existential authenticity, tapping into the essence of the human without heed to social conventions or received ideas.

The notion that Kerouac practiced an unadulterated form of in-the-moment improvisation is exaggerated, if not downright erroneous, for at least four reasons. One is evident in his “Essentials of Spontaneous Prose,” which begins, “The object is set before the mind, either in reality … or … in the memory wherein it becomes the sketching from memory of a definite image-object.” However fast and fluid the writing process may be, it does not seem wholly extemporaneous if the work’s content, direction, and final form are directly linked with a concrete image held deliberately and continually in consciousness. A second reason is that Kerouac was keenly attuned to the cultural environment in which he lived and worked, and he drew the verbal materials of his novels, stories, and poems directly from his surroundings; like a journalist or anthropologist, he did not so much originate as chronicle the linguistic tenor of the current scene. Henry Miller put it well in a preface to Kerouac’s novel The Subterraneans: “He ‘invented it,’ people will say. What they should say is: ‘He got it.’ He got it, he dug it, he put it down.”

A third factor that calls the purity of Kerouac’s spontaneity into question is the key role of memory in his work. Kerouac had a great gift for recollection—he was nicknamed Memory Babe in childhood—and he was always jotting things in his notebooks for future reference. Beyond this, he had such a verbally oriented sensibility that words were part of everything he did; while participating in a physical activity he would also be putting words together mentally, according to his biographer Gerald Nicosia, and writing or typing them later was just another step in the process. Kerouac also had the habit of replaying experiences over and over in his mind, refining their linguistic equivalents in exquisite detail before putting them on the page. Revision was his enemy, but what Cassady called “prevision” was a valuable friend.

And finally, there is really no such thing as pure improvisation. The most brilliant jazz musician does not make things up out of the air or the unconscious, but relies on whole sets of melodic riffs, harmonic ideas, rhythmic maneuvers, structural options, and the like that have been learned, practiced, and assimilated long before they leap out at listeners in seemingly extemporaneous ways. None of these points are meant to diminish Kerouac’s luster as a stylist, an innovator, and an influence on modern American literature. His stature is more than imposing enough to stand without support from overstated claims of improvisatory genius that somehow springs from the innermost self without picking up cultural baggage along the way.

Although the journeys of On the Road represent the epitome of Beatness for many readers, Kerouac first expressed his fascination with traveling, rambling, and the lure of far-away places in his previous novel, The Town and the City, where he divided various aspects of his personality among three brothers: a football-playing college dropout, a working-class wanderer, and an intellectual skeptic. The action moves to many locations, emphasizing the tensions Kerouac felt between the dull but calming atmosphere of small-town living, on one hand, and the exciting but dangerous lure of urban life, on the other. Although this novel is frequently written off as a square attempt to imitate the density and sprawl of Kerouac’s then-hero Thomas Wolfe, it is marked throughout with Kerouac’s own artistry and honesty.

With some exceptions, travel is not the focus of Kerouac’s next few novels. Doctor Sax: Faust Part Three, written in 1952 and published in 1959, is an extended fantasy-meditation-reverie on people, places, and events of his early life. Maggie Cassidy, written in 1953 and also published in 1959, is a straightforward romance set in a town very much like the small Massachusetts city where Kerouac grew up. The Subterraneans, written in autumn 1953 and published in 1958, takes place in San Francisco, where the Kerouac stand-in Leo Percepied has an ultimately sad love affair with a young black woman. Tristessa, written in 1955/56 and published in 1960, is a love story with a Mexican background. Visions of Gerard, written around the time Tristessa was finished and published in 1963, grew from Kerouac’s poetic reminiscences of his sainted brother.

A novel from this period that does engage with travel is Visions of Cody, published in 1960 but written in 1951/52, soon after On the Road was finished. Here travel is not too important for its own sake, though; it serves mostly as kinetic punctuation for another study of Kerouac’s relationship with Neal Cassady, the title character’s real-life counterpart. Visions of Cody is in fact a reworked and far more experimental version of On the Road, so fragmented and improvisational in style that it makes the earlier novel seem almost conventional. The next Kerouac novel where travel plays a central role is The Dharma Bums, written in late 1957 and completed early the following year. Its theme is the quest for Buddhist enlightenment, and the first chapter finds the Kerouac surrogate Ray Smith riding toward Northern California on a boxcar with a drifter who is actually a dharma bum—a person fulfilling the obligations of the spirit (dharma) while appearing downtrodden and beat up (like a bum) in society’s eyes. After getting to Berkeley, Ray has long talks with the Gary Snyder stand-in Japhy Ryder, whose attunement to Zen serenity is more advanced than Ray’s understanding. Another key character is the Allen Ginsberg surrogate Alvah Goldbrook, who cares more about kicks (at this point in his life) than religion. Ray and Japhy go to the Sierras for mountain climbing; Ray takes a break back east with his boring family, then returns to Berkeley; and Japhy ultimately heads for Japan while Ray climbs up Desolation Peak to continue his quest for illumination.

The title of Desolation Angels, written between 1956 and 1961 and published in 1965, refers most obviously to the isolated mountaintop where Jack Duluoz seeks monk-like seclusion by working as a fire lookout. Yet the story’s settings include Tangier and Mexico as well as trusty New York, the usual Kerouac home base. Big Sur, written in 1961, finds Jack Duluoz fleeing his newfound fame as an author by traveling to a Northern California cabin lent to him by a friend. His initial delight in nature gives way to psychological and physical torments caused by his alcoholism.

Kerouac’s goal as a novelist was to unite his major novels into a massive “Legend of Duluoz” cycle, giving consistent names to the characters so the saga could be read as a vast autobiographical epic. Considered as a unified whole, his books clearly deal with two kinds of travel: journeys through the world that energize fast-moving novels like On the Road and The Dharma Bums, and journeys through the self that lend reflective depth to inward-looking novels like Doctor Sax and Visions of Gerard. Often these different kinds are woven into one story, as happens in the early Town and the City and the late Vanity of Duluoz: An Adventurous Education, 1935–46, published in 1968. Although both varieties were important to him, Kerouac was more committed to the inner journeys than to the outer ones, despite the travelin’-man image that On the Road affixed to him. Even the nomadic On the Road allows time for serious thoughts about serious things, such as Sal’s reluctant awareness that Dean lacks moral depth. Introspection is key to every Kerouac story, including minor ones like the novellas Pic (started in 1951, finished in 1969, published in 1971) and Satori in Paris (completed in 1965, published in 1966).

Kerouac kept up his inner explorations as long as he could, pondering the world—and himself in the world—even as he barreled down its highways, meditated on its mountaintops, sought solace in its barrooms and saloons, and plumbed its possibilities for joyful camaraderie and spiritual intoxication. Sadly, though, introspection put Kerouac in touch with things his fragile soul couldn’t bear, fostering the disillusionment and drinking that led to his death.

What happened to dim Kerouac’s star so drastically? There are numerous answers, including sudden fame, too much alcohol, and psychological problems that had been festering since childhood. He did not stop producing books—the marvelous Vanity of Duluoz was finished and published the year before he died—but he spent most of his last years drinking, puttering, drinking, listening to jazz, drinking, and watching television with his mother in the various houses they shared.

Mémêre was part of the problem. Kerouac was profoundly reliant on her, fleeing to her throughout his life when he needed comfort, rest, and respite from the outside world. But there was a perverse aspect in their relationship that grew more pronounced in his later years. Recalling his last visit to their Long Island house, Ginsberg reported a weird rapport between the two in the documentary film What Happened to Kerouac? “I never heard such language in my life as Jack used on his mother and his mother used on Jack,” says the poet, who had surely heard some mighty pungent language in his time. “He was calling her a filthy old fish-cunt [and saying] ‘Get out of here, you old whore!’ Awful language, both of them drunk.… She was as much of an alcoholic as he was, according to him! That was no secret—they would drink together in those years.… They both sounded crazy. It was like a scene in some really amazing, degraded Zola novel.”

The Beat scholar Ann Charters describes Mémêre as an intelligent, capable, down-to-earth woman—and yet she basically concurs with Ginsberg’s opinion. Charters recalled in What Happened to Kerouac? that during one of her visits,

He said, “You’re the only woman I’ve ever wanted to marry, ma.” Then he got up and left the room.… And she said to me, “You know, when he was drunk last week, he threw a knife and I ducked and it hit right there.” There was a kind of fantasy going on in that house.… Then he comes back in the room, and they were playing like a very badly married couple, frankly. “Did you show her that?! Did you show her that?! I told you not to show her that!” I said, “Okay, good night, you guys, I’ll see you tomorrow.”

Alcoholism was the most obvious symptom of Kerouac’s decline. Some saw this as a moral weakness, but it was more likely a form of self-medication for some variety of depression or bipolar disorder. Whatever the cause, it had awful consequences. By 1968 he was unkempt and overweight, drinking twelve to fifteen shots of whiskey and gulps of beer every hour, according to a Boston Globe interviewer who visited him. It is amazing that an interview actually resulted from this visit. Kerouac’s first comment in it is, “If I didn’t have my Scotch and beer I wouldn’t speak to anybody.”

Kerouac had an attraction-repulsion attitude toward alcohol. He admitted he was drinking himself to death—as a Roman Catholic, he felt “real” suicide was not an option—and he wrote in a 1962 letter, “Alcoholism is by all odds the only joyous disease, at least!” He died of it in October 1969.

In 1944 an event took place that troubled Kerouac as well as Burroughs and Ginsberg, helping to catalyze the unhappy outlook on life that characterizes some early Beat writing. The main players in this tragedy were Lucien Carr and David Kammerer.

Kammerer had been a friend of Burroughs since childhood, and in 1933 they had visited Europe together. Burroughs found him “always very funny, the veritable life of the party, and completely without any middle-class morality.” Kammerer became an instructor at Washington University in St. Louis, and he also ran a youth group that Carr joined while still a boy. By all reports, Kammerer was infatuated and then obsessed with Carr, a well-to-do Columbia student whom Kerouac describes in Vanity of Duluoz as a young man of “fantastic male beauty … actually like Oscar Wilde’s model male heroes.”

They traveled to Mexico together in 1940, with permission from Carr’s mother. After finding some of Kammerer’s letters, however, the shocked mother worked hard to keep them apart. Kammerer then followed Carr to each of several schools he enrolled in. Carr evidently had no interest in a homosexual relationship, but he appeared to enjoy the attention his older friend lavished on him, especially when the former English teacher ghost-wrote his college homework. Carr transferred to Columbia in 1943, with Kammerer and Burroughs trailing along. Soon Kammerer met Ginsberg and Kerouac, becoming part of the fledgling Beat circle.

Kammerer and Carr were an odd couple with a penchant for trouble, ranging from childish horseplay to deep emotional crises. An instance of the latter arose in 1943, when Carr landed in a mental institution after an apparent suicide attempt. The already unstable mood of their friendship took another downturn when Carr fell in love with a young woman. Kammerer stalked Carr on some days and refused to see him on others. The tension between them finally exploded on a summer night in 1944. Kammerer had been hunting for Carr that evening, eventually finding him drunk in the West End, a bar in the Columbia neighborhood. They left the bar together, and later in the night they came to blows on a hillside not far away.

According to Ted Morgan’s account, Carr then went to the apartment that Burroughs was sharing with Kerouac and Edie Parker, telling them what had happened next and throwing Kammerer’s eyeglasses onto a table. “I just got rid of the old man,” Carr said. “I stabbed him in the heart with my Boy Scout knife.” Kerouac asked why. Carr answered, “He jumped me. He said I love you and all that stuff, and couldn’t live without me.” He added that Kammerer had threatened to kill both him and his girlfriend. After stabbing Kammerer, the young man had tied stones onto the body’s arms and legs, using strips torn from the shirt. Then he had pushed Kammerer’s body into the Hudson River, where it hovered until Carr waded in up to his chin and pushed it into the current.

Burroughs advised Carr to turn himself in and make a plea of self-defense. Taking a very different tack, Kerouac went with Carr to the scene of the crime, where Carr buried the incriminating glasses and dropped his knife into a sewer. Then they went for drinks and watched a movie. Two days later, Carr took Burroughs’s advice and surrendered to the police, reaching a plea bargain that reduced a possible twenty-year sentence to two years of actual time served, and placed him in a reformatory rather than a penitentiary. He left the reformatory a changed man, so eager for a conventional life that he complained when Ginsberg later dedicated “Howl” to him.

Burroughs and Kerouac, considered material witnesses to the crime, were arrested for not reporting it. Burroughs’s family bailed him out immediately. Kerouac’s humiliated father refused to follow suit, so Parker put up the money on the condition that Kerouac marry her. He did. Ginsberg was not hauled into the legal system, but he was deeply shocked by what had happened, fearing it was a horrific consequence of the morbidly tinged romanticism in which he and his friends had indulged. He soon started a novel, The Bloodsong, based on the incident. Kerouac wrote about the tragedy in I Wish I Were You, a novella that also went unfinished. He later wove the affair into his first novel, The Town and the City, and his last, Vanity of Duluoz. In its immediate aftermath, Kerouac and Burroughs used it as the basis for their attempt at a joint novel, And the Hippos Were Boiled in Their Tanks, writing under pseudonyms and borrowing their title from a news report about a circus fire. They found an agent, but nobody would publish it.

There is no particular moment when the Beat Generation was born, but one might say it all started with Burroughs’s birth in 1914, since he was the oldest member of the group. Although he was fond of saying he did not come from a very privileged background, his full name was William Seward Burroughs II and his eponymous grandfather was William Seward Burroughs, inventor of the Arithmometer, an adding machine with a tongue-twisting name. It sold well, and old Burroughs went on to establish the renowned Burroughs Adding Machine company. Burroughs’s mother, Laura Lee, was descended from Robert E. Lee, another adornment to the clan’s all-American profile. The family fortune had declined by the time Burroughs II entered the world, but his parents were still solvent enough to support him during a considerable portion of his life. He declared that money was never a problem for him until he picked up his drug habit.

Burroughs prided himself on eccentricity, cultivating it from childhood. The four-year-old Burroughs was befriended by a nanny who taught him curses and incantations; the eight-year-old Burroughs presided over a hideaway equipped with tools for secret chemical experiments; the preteen Burroughs was sallow and withdrawn. A more “normal” person might have wanted to repress memories of such a peculiar childhood, but Burroughs enjoyed playing with bizarre self-images in his fiction. In his 1983 novel The Place of Dead Roads, for instance, the protagonist Kim Carsons—“a slimy, morbid youth of unwholesome proclivities with an insatiable appetite for the extreme and the sensational”—overlaps with a writer character named William Seward Hall, an obvious stand-in for the author. Another character says Kim looks like “a sheep-killing dog,” and still another calls him “a walking corpse.” Burroughs reveled in his lifelong ability to make unsettling impressions on strangers and acquaintances alike.

After attending various private schools, at least one of which expelled him for experimenting with drugs, Burroughs entered Harvard University, where he studied English and (during a short graduate-school stint) anthropology. His college digs in Cambridge, Massachusetts, were close enough to New York City for Burroughs to make frequent visits there, discovering places in Harlem and Greenwich Village where his interests in drugs and homosexuality were easily indulged. He also pursued his longtime fascination with weapons, especially guns.

After graduating from Harvard he visited Europe on his parents’ money, wondering what he should do next. One idea was to become a psychoanalyst, so he studied medicine in Vienna for a little while, but it was already clear that sex, drugs, and writing had a stronger grip on him. Before returning to the United States he married a Jewish woman to help her evade Austria’s brutal Nazi regime. Their eventual divorce was no surprise, since it was entirely a marriage of convenience and Burroughs was confirmed in his gay identity by then, despite occasional attempts (which Ginsberg also made) to “correct” the condition through therapy. He was twenty-five when he started his first monogamous gay relationship. When it turned sour, he expressed his disappointment with a wildly romantic-masochistic gesture, cutting off part of his left little finger with a pair of poultry shears.

In 1940, a year before America entered World War II, Burroughs was living with his parents, delivering items for the gift shop they owned in St. Louis, and hating every minute. Deciding to escape by joining the navy, he failed the physical exam, which disappointed him because he thought combat might be fun. He then took flying instruction and applied for the Glider Corps, which refused him because his eyesight was weak. His next rejection came from a volunteer organization called the American Field Service, where the recruiter was bothered by his behavior at college. Always interested in espionage and intrigue, Burroughs then used a family connection to approach the brand-new Office of Strategic Services, a wartime predecessor of the Central Intelligence Agency, but again his history of college antics shot him down; this time the decision lay with a former Harvard housemaster who had chided him for keeping a ferret in his room.

Burroughs managed to join the army in early 1942, but grew angry when he realized he would be an ordinary soldier instead of an officer. His mother engineered a “civilian disability” discharge for him, on the grounds that accepting someone this psychologically unstable had obviously been a mistake on the army’s part. Getting out of the service took months, during which Burroughs read Marcel Proust’s Remembrance of Things Past. He then moved to Chicago and worked in various unglamorous jobs; several months as an insect killer provided material for his early book Exterminator! He migrated to New York when his friends Carr and Kammerer moved there in 1943. By the next year Burroughs was living with Joan Vollmer, his common-law wife (his marriage to the Viennese woman had ended) in an apartment shared with Kerouac and his girlfriend. Before long the full array of Beat behaviors were on display: Burroughs became addicted to morphine, Vollmer did the same with Benzedrine, and in 1945 Burroughs and Kerouac began their collaborative novel And the Hippos Were Boiled in Their Tanks, which was never completed (although it was ultimately published in 2008) but could later be seen as a significant step on the road to the as-yet-unnamed Beat movement.

Burroughs’s first serious writing effort had also been a collaboration. In 1938 the twenty-four-year-old Harvard graduate had sat down with his lifelong friend Kells Elvins to write a story called “Twilight’s Last Gleamings,” inspired by a shipwreck they had read about. Bits of the story were spliced into Nova Express and other Burroughs works many years later, and eventually he reconstructed the original version, which had been lost or destroyed, from memory.

Parts of “Twilight’s Last Gleamings” show the Burroughs touch already flowering, as when it tells about an explosion at sea accompanied by the sound of jazzman Fats Waller singing “The Star-Spangled Banner” on a jukebox. A sample:

Dr. Benway, ship’s doctor, drunkenly added two inches to a four-inch incision with one stroke of his scalpel.

“There was a little scar, Doctor,” said the nurse.… “Perhaps the appendix is already out.”

“The appendix out!” the doctor shouted. “I’m taking the appendix out! What do you think I’m doing here?”

“Perhaps the appendix is on the left side,” said the nurse. “That happens sometimes, you know.”

“Can’t you be quiet?” said the doctor. “I’m coming to that! … Stop breathing down my neck! … And get me another scalpel. This one has no edge to it.… I know where an appendix is. I studied appendectomy in 1904 at Harvard.”

Dr. Benway, who became one of Burroughs’s most enduring tragicomic creations, was clearly gestating in the writer’s imagination many years before Naked Lunch made both of them famous.

Burroughs was skilled at entertaining friends with “routines,” spontaneous eruptions of witty performance based on character ideas and imitations. His talent for these was a factor in his choice of literature as a career path. But far more important than this or the Carr-Kammerer affair were two turning points that Burroughs reached in the early 1950s, when he was living in Mexico City with Vollmer.

The first was his realization that his experiences as a heroin addict might be good story material. Summoning up memories of the drug scene, Burroughs started work in early 1950 on Junk, which would become Junkie: Confessions of an Unredeemed Drug Addict, his first published novel. Ginsberg’s friend Carl Solomon had an uncle who worked at Ace Books, which published low-price paperbacks. Burroughs signed a contract with Ace in 1952, and in a year the volume was on bookstore shelves under the nom de plume William Lee.

The other turning point was a trauma that Burroughs later claimed was pivotal to his vocation as a writer. The year was 1951; the place was an apartment in Mexico City, where Burroughs had fled with Vollmer to avoid a possible prison sentence for drug dealing in New Orleans, where they had lived for a short time. The occurrence was Vollmer’s death at Burroughs’s hands. Burroughs was notorious for playfully scrambling the facts of his personal history, but his feeling of remorse after killing Vollmer was so strong that there is little reason to doubt the basic truthfulness of his own account, if not the accuracy of every detail. As he remembered it, he and his wife were in a friend’s apartment, sitting about six feet away from each other. The fatal gun

was in a suitcase and I took it out, and it was loaded, and I was aiming it. I said to Joan, “I guess it’s about time for our William Tell act.” She took her highball glass and balanced it on top of her head. Why I did it, I don’t know, something took over. It was an utterly and completely insane thing to do.… I fired one shot, aiming at the glass.

He fired too low, hitting Vollmer in the side of her head and killing her instantly.

Aside from the hard facts of the case, there is the unavoidable question of why it happened. It is possible that something deeply negative had been brewing in Burroughs’s unconscious, leading him to a destructive act that seemed accidental but had its origin in his own psyche. This could explain the presentiment he seemed to feel earlier on the fatal day, “a feeling of loss and sadness that had weighed on me all day so I could hardly breathe,” he later recalled, “intensified to such an extent that I found tears streaming down my face … the overwhelming feeling of doom and loss.”

It is also possible, however, that Vollmer’s own unconscious was at least partly to blame. According to Ginsberg, she “had amphetamine psychosis and was drinking a bottle of tequila a day.” Only a week earlier Ginsberg had accompanied her and Carr on a “nightmarish” road trip through the Sierras, cowering in the backseat (with the couple’s children, one theirs and the other Vollmer’s from an earlier relationship) as Carr sped “down hairpin dirt-road mountain turns” and Vollmer pushed him to go even faster. After talking with everyone who had been present about who really initiated the William Tell routine, Ginsberg had an impression that diverged somewhat from Burroughs’s version, putting more stress on Vollmer’s self-destructive impulses.

Whatever the true reason for it, Vollmer’s death galvanized Burroughs’s creative energy. “I am forced to the appalling conclusion,” he admitted in the introduction to his novel Queer,

that I would never have become a writer but for Joan’s death, and to a realization of the extent to which this event has motivated and formulated my writing. I live with the constant threat of possession, and a constant need to escape from possession.… So the death of Joan brought me in contact with the invader, the Ugly Spirit, and maneuvered me into a lifelong struggle, in which I have had no choice except to write my way out.

Burroughs favorably impressed Mexican officials by conscientiously obeying the conditions for his bail, but after repeated postponements of his trial for culpable homicide he returned to the United States, ultimately receiving a two-year suspended sentence. He then traveled to South America, and by the mid-1950s he was living in Morocco, writing a prolific stream of stories, articles, and long letters to Ginsberg, whom he wooed by mail until finally accepting the fact that Ginsberg was firmly committed to Peter Orlovsky, the poet who would be Ginsberg’s lifelong partner. Ginsberg often acted as a literary agent for his friends, so Burroughs sent him various stories, which Ginsberg edited and (when appropriate) pitched for publication.

Burroughs also sent Ginsberg a longer manuscript called “Interzone,” which he hoped would be accepted for publication by City Lights Books, the San Francisco bookshop and publisher founded by Lawrence Ferlinghetti and Peter D. Martin in 1953. City Lights rejected it, as did Olympia Press in Paris, even though both enterprises were notably daring and innovative in their activities. Ginsberg then sent a portion of it to the Chicago Review, and when the University of Chicago vetoed it for publication in the journal, an editor published it as the first issue of a new magazine called Big Table. The title had been changed to Naked Lunch, and when Olympia Press then changed its mind and published the entire work in 1959, the most controversial of all Beat novels was officially launched—a work cheerfully confrontational and zealously obscene in its uproarious commingling of violent sex, sexy violence, death, dope, addiction, science fiction, farce, eschatology, explosive love, corrosive hate, and acidic satire aimed at every American target from capital punishment to capitalism.

Creating this extraordinary book was an extraordinary experience. In 1956 Burroughs wrote to Ginsberg that “it is coming so fast I can hardly get it down, and shakes me like a great black wind through the bones.” Leaving behind the relatively straightforward prose of Junkie and the still-unpublished Queer, he had found a new, revolutionary style as outrageous and unprecedented as the subject matter he was tackling. Naked Lunch plunges readers into a universe where boundaries between reality and fantasy are indistinguishable amid the seething word-storms of torrential prose. Some of the novel’s different sections are similar in their language, while others fiercely collide with one another in style and ideas. Two things loosely hold them together: the presence of William Lee, a surrogate for Burroughs, and the ubiquity of addiction and homosexuality. These are seen as both deeply rooted impulses and metaphors for human need in a largely dehumanized world that spawns insensitivity and greed as naturally as the merciless sun passes through the blazing sky.

Naked Lunch introduces images and phrases that would surge through Burroughs’s prose forever after. Among the most disturbing is his vision of a man hanging from a noose, dying in convulsions as his erect penis spews copious sperm onto the eager faces and bodies gazing excitedly from below. This is a situation Burroughs never tired of resurrecting, even in the trilogy of late novels (Cities of the Red Night, The Place of Dead Roads, The Western Lands) that capped his career in the 1980s. Such stuff is wildly outrageous by conventional standards, and Naked Lunch sparked censorship as “Howl” had done before it. In 1962 it was banned in Boston, where novels like Erskine Caldwell’s 1933 God’s Little Acre and Henry Miller’s 1934 Tropic of Cancer had run into trouble earlier. It also went on trial in a Los Angeles court; the California judge decided the book was not obscene, but only in 1962 did the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court finally allow it to be freely circulated.

During this period Burroughs moved from Morocco to Paris, staying with Ginsberg, Orlovsky, and Gregory Corso at what they called the Beat Hotel, a run-down rooming house popular with bohemians. An avant-garde writer and painter named Brion Gysin also lived there, and Burroughs grew enthusiastic about Gysin’s commitment to the “cut-up” method of creative work, which relies on slicing, tearing, or otherwise dividing artistic materials—written texts, voice recordings, film strips, whatever—into malleable segments that can then be rejiggered and reconnected in novel configurations. Similar methods had been explored by Dadaists and Surrealists, who had (for just two examples) made poetry by drawing words out of hats and formed pictures by joining fragments without looking at them; but Burroughs believed that Gysin’s technique held possibilities way beyond those uncovered by their predecessors. Soon he was cutting up, folding over, and connecting words and pictures into patterns determined by chance and the unconscious rather than the ego-driven conscious mind.

In addition to making hundreds of collages, photomontages, and tape-recorded works, Burroughs used cut-up and fold-in methods to craft revised editions of his 1961 novel The Soft Machine and its 1962 sequel The Ticket That Exploded, the first two books of the Nova trilogy. (The trilogy concludes with Nova Express, published in 1964 and so experimental in its original form that Burroughs didn’t change it.) His passion for the cut-up and fold-in techniques was so strong that at one point he thought the results could predict the future. He calmed down eventually, though, realizing that even avant-garde breakthroughs have their limitations and acknowledging the pros and cons of the new methods with candor and practicality. The great virtue of cut-up techniques, he said, is the room they allow for spontaneity and chance; the best writing “seems to be done almost by accident,” but “writers … had no way to produce the accident of spontaneity” until he and Gysin learned to produce it by cutting and folding. On the negative side, he admitted that “you do have to compose the materials … [Y]ou can’t just dump down a jumble of notes and thoughts and considerations and expect people to read it … I’ve done writing that I thought was interesting, experimentally, but simply not readable.” So he rewrote, revised, and rearranged his “jumbles” of dissected prose until they carried some degree of sense that readers could actually grasp. His name has been firmly linked to the cut-up ever since.

5. “The Death of Mrs. D,” a mixed-media collage by Brion Gysin and William S. Burroughs. Named for a character in Nova Express, the third novel in Burroughs’s ambitious Nova trilogy, this work reflects Burroughs’s intense fascination with cut-and-paste aesthetics, which played a powerful role in shaping his prose as well as the visual art that he and Gysin created together.

Burroughs lived mainly in London during the 1960s, working with Gysin and the mathematician Ian Sommerville on various projects, and collaborating with the filmmaker Antony Balch on the 1963 movie Towers Open Fire and other underground shorts. In 1971 Burroughs published Ali’s Smile: Naked Scientology, a book comprising a short story and a number of essays and articles related to the Church of Scientology, which he had joined a few years earlier in the hope that its combative stance toward culturally induced thought and behavior might be a useful weapon against the control mechanisms that he believed are ubiquitous in modern society. But by 1970 he concluded that Scientology itself amounted to an authoritarian system, even though some of its ideas and practices could be useful in the search for mental freedom. Literature, he decided, is the best battleground on which to fight and conquer the tyranny of language.

Returning to New York in 1974, Burroughs became a part-time English professor and read from his books on stages across the country. By the time Cities of the Red Night appeared in 1981 he was back on heroin, and partly to overcome this setback he relocated to the Midwest, where he moved more deeply into visual art with his literally explosive “shotgun paintings,” created by shooting at paint cans positioned in front of canvases. He finished his last novel, The Western Lands, in 1987. He also participated in new collaborations—with the stage director Robert Wilson, Tom Waits, and Keith Haring, among others—and oversaw the publication of his journals and other overlooked texts. He died in Lawrence, Kansas, on August 2, 1997, at the age of eighty-three, living far longer than skeptics had ever thought possible for the most incorrigible bad boy of the Beats.