Allen Ginsberg gave a thumbnail account of his early years on the back cover of Howl and Other Poems, published in 1956 and still his most famous book:

High school in Paterson till 17, Columbia College, merchant marine, Texas and Denver, copyboy, Times Square, amigos in jail, dishwashing, book reviews, Mexico City, market research, Satori in Harlem, Yucatan and Chiapas 1954, West Coast 3 years. Later Arctic Sea trip, Tangier, Venice, Amsterdam, Paris, read at Oxford Harvard Columbia Chicago, quit, wrote Kaddish 1959, made tape to leave behind & fade in Orient awhile.

Not surprisingly, much personal drama, artistic excitement, and spiritual derring-do lie behind those easily stated facts.

Ginsberg grew up in a politically active Jewish home. His father was a schoolteacher and poet, his mother was a left-wing activist, and Allen went to Communist Party meetings as a child. He was arguably the most serious intellectual of the early Beats, even if Columbia University, where he enrolled in 1943, did suspend him for vandalism and for (probably) having a homosexual fling on campus. It was at Columbia that he developed friendships with Kerouac and Carr, who were students there, and Burroughs and Cassady, who were not. He had a brief affair with Cassady, who was basically heterosexual but wanted Ginsberg to help him with his writing.

Ginsberg was a born bohemian, and these bohemian friends made him still more bohemian, to the point where he openly acknowledged his homosexuality at a time when same-sex relationships were taboo in “polite” society. Unlike his best friends, he had considerable interest in political issues; when he started college he was hoping to become a politician and labor lawyer. But he already loved poetry, and it wasn’t long before writing replaced his original plan. Along with his own predilections, this change reflected the influence of his father, Louis Ginsberg, a New Jersey high school teacher and recognized poet. Writing for his friends, the Columbia literary magazine, and his own improvement, Allen produced a copious amount of verse while at the university, most of it incorporating traditional structures and techniques, including rhyme. This pleased his poetic father, who believed in rhyme, meter, and stanzas as means for imposing aesthetic order on the endless universe of words. Allen also studied the works of his favorite poets. They included the eighteenth-century English poet Christopher Smart, who like Ginsberg spent time in a mental institution, and the nineteenth-century American bard Walt Whitman, who like Ginsberg was gay.

In the summer of 1945, a few months after Columbia suspended him, Ginsberg decided to enlist in the merchant marine, as Kerouac had done. Joining the U.S. Maritime Service, he found it more mindless and less romantic than he ever dreamed. Making matters worse, he caught pneumonia, was accused of malingering when he requested medical care, and offended his superiors by vomiting in an off-limits lavatory. “By god those effete degenerates of Columbia were more disciplined and serious than this dreamworld,” he wrote to his brother at the time. He made the most of his sick leave by reading a lot, though, and returned to civilian life as soon as his enlistment time was over.

At least three subsequent events can be called turning points in Ginsberg’s life. The first happened in 1947, when psychiatrists at Pilgrim State Hospital on Long Island decided that the mental condition of his schizophrenic mother, Naomi Ginsberg, had deteriorated so badly that only a lobotomy could give her some relief. Ginsberg’s parents were divorced, so responsibility for giving informed consent fell to Allen, who signed the papers with great misgivings and felt guilty about it for years to come. His mother had introduced bizarre psychological currents into the home—she was a household nudist, among other things—and living with her had shaped Allen’s early life in strange, sometimes unwholesome ways, as his poem “Kaddish for Naomi Ginsberg (1894–1956)” brilliantly and poignantly shows. But his compassionate nature led him to suffer along with her, and his own instability as a young man surely caused him to identify with her all the more.

The next turning point came in 1948, when Ginsberg had a vision of the poet and artist William Blake reciting verses from his 1794 collection Songs of Experience, miraculously reaching Ginsberg from beyond the barrier separating death and life. The life-changing impact of this mystical experience affirmed his conviction that he was destined to be a spiritually attuned poet and a forceful advocate of the New Vision, the vaguely defined aesthetic agenda dreamed up by Ginsberg and his friends.

It also increased the fear of Ginsberg’s friends and father that Allen might be mad, suffering now from auditory hallucinations. Ginsberg was certainly in a psychologically delicate condition, and in 1949 his stability was further undermined by an incident that many young men might have quickly shaken off: he was arrested and briefly locked up after a few lawbreaking friends (the writer and petty thief Herbert Huncke among them) persuaded him to allow stolen goods into his apartment, leading to a police chase that ended with the wreck of the malefactors’ stolen car. As a condition of getting out of jail, Ginsberg became an in-patient at the Psychiatric Institute of Columbia Presbyterian Hospital, remaining there for almost a year. Perhaps the most lasting consequence of his institutional stay was the friendship he struck up with Carl Solomon, the fellow patient and fellow spirit to whom he later dedicated “Howl,” his great breakthrough poem of 1955. After his discharge in February 1950, Ginsberg led a more “adjusted” life for a while—taking a regular job, going into psychoanalysis, and trying (not for long) to be heterosexual. He also went about seeking and finding other poets he admired, including William Carlos Williams, who shared his New Jersey roots, and Kenneth Rexroth, whom he met during a San Francisco visit.

Ginsberg reached his third turning point in 1955, when he chanted the first portion of the unfinished “Howl” at the 6 Gallery reading. This lifted his self-confidence, cemented his friendship with the circle of San Francisco poets, and led to the publication of his first book (Howl and Other Poems) the following year. It is difficult to overstate the importance of “Howl” to Ginsberg’s artistic development and to the evolution of the Beat literary aesthetic. Its key features included a rejection of rhyme, meter, and the precepts of the analysis-heavy New Criticism regarding form; long, breath-based lines packed with meanings and associations; forthright treatments of sex, drugs, and insanity; surreal word pictures (“negro streets,” “unshaven rooms,” “hydrogen jukebox”) and hallucinatory imagery; hypnotic repetitions; and, in the first portion, a powerfully expressive taxonomy of words and actions conjuring up the travails of a generation driven to madness by a spiritually dead culture. It remains a unique achievement to this day.

The success of “Howl” helped other people as well as Ginsberg himself, since he used his newfound fame to begin his lifelong labors as an amateur literary agent for friends and other creators of worthy poetry and prose. As happened with Burroughs a few years later, Ginsberg received an added measure of celebrity when Howl and Other Poems went on trial for obscenity.

In the minds of many mainstream citizens, and in the morality strictures of the American legal system, the elevated literary pedigree of “Howl,” rooted in the poetry of Blake, Whitman, Williams, and Hart Crane, could not counterbalance its graphic references to illegal drugs and illegal sex. In a deeply homophobic era, the work’s most courageous element was Ginsberg’s uncompromising candor about his homosexuality, and this is what spurred the charges that brought the publisher and poet Ferlinghetti into the San Francisco courtroom of Judge Clayton W. Horn, who heard extensive testimony on both sides of the issue and ultimately ruled that the poem had “redeeming social importance” and was therefore not obscene under the law.

Due in part to the attendant publicity, Howl and Other Poems sold more than 10,000 copies before the “not guilty” decision came in. Ginsberg was traveling in Morocco and Europe with Orlovsky at the time, but he knew from afar how important the trial was to his reputation, and to the principle of free speech, which was violated all too often in those benighted days despite its enshrinement in the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution. The trial and its context are dramatized instructively and effectively in the 2010 movie Howl, a mixture of docudrama and animation directed by the team of Rob Epstein and Jeffrey Friedman, with James Franco portraying the young Ginsberg.

“Howl” and “Kaddish” are Ginsberg’s most deservedly renowned poems, and “Howl” contains some of the best-known opening words in American poetry: “I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness, starving hysterical naked/dragging themselves through the negro streets at dawn looking for an angry fix …” These long lines, clearly influenced by Whitman, are part of an even longer line, since Part I of “Howl” is a single sentence running to a dozen pages in the Pocket Poets edition. In this work Ginsberg’s versification took on the forthright, pulsing form it essentially retained in nearly all his major works to come. Part I is the most autobiographical portion, referring to favorite poets from Blake to Edgar Allan Poe, and to other admired figures, from Cassady and Burroughs to Jesus and Plotinus, the neo-Platonist philosopher. It also names cities, hospitals, pranks, tragedies, journeys, and a staggering number of other things that had figured in his experience. It is an account of, a testament to, and a lamentation over the physically, psychologically, and spiritually complex life he had lived so far.

Part II is still more incantatory, beginning most of its lines with the name of the Old Testament god Moloch, to whom children were sacrificed. In the emerging Ginsberg mythos, Moloch represents modern industrialized society, which has destroyed and devoured many of the people named earlier in the poem. “Howl” was written “for Carl Solomon,” the friend Ginsberg made in the mental hospital, and Part III speaks directly to Solomon through its mesmeric repetitions of “I’m with you in Rockland” at the beginning of every line. The poem then ends with a two-page “Footnote to Howl” that starts with fifteen invocations of the word “Holy” and goes on to name a dazzling variety of people, places, and things that deserve this consecrating term, including such seemingly contradictory ones as “ecstasy” and “suffering.” Ginsberg was not yet a thoroughgoing Buddhist, but the conclusion of “Howl” zestily reflects the all-embracing Zen spirit.

Ginsberg wrote the core of his other masterpiece, “Kaddish,” in Paris, during a forty-hour marathon of spontaneous writing propelled by Dexedrine and coffee. It is said that he cried copiously as he set down the poem in longhand, wetting the pages under his eyes. The poem’s subject is the life and death of Naomi Ginsberg, his profoundly troubled mother, whose funeral he had missed because he was on the West Coast and couldn’t get back to New York in time. Kaddish is a traditional Jewish prayer for the dead, and it had been omitted from the funeral because the necessary number of men (a minyan) had not been present. Still enough of a visionary Jew to regret this deeply, Ginsberg spent an intoxicated night chanting the prayer with a friend, and this was vivid in his mind when he sat down to write.

As with “Howl,” the poem unfolds in sections. The first conjures up memories of the Lower East Side, the poor Manhattan neighborhood where the immigrant Naomi had lived as a girl. The second, more extraordinary portion gives a poetic-narrative account of Ginsberg’s life with his family, expressing his desperate desire to reach a state of understanding and a sense of forgiveness with them all. Allen’s father and brother are portrayed here, but the focus remains his mother, with all her tragic shortcomings of mind and body, including what Ginsberg perceived as a demented kind of sexual seductiveness that she directed at him in his boyhood.

The third section is a prayer for remembrance of things past, and the fourth section is an incantation—the phrase “with your eyes …” begins line after line—meant to etch memories of that which has been lost into his mind as he writes, and into our minds as we read. The last portion imagines Naomi’s grave and the calling of crows clustering around it. At the end, Ginsberg’s pure poetry verges on the universality of pure sound:

Lord Lord Lord caw caw caw Lord Lord Lord caw caw caw Lord

The meaning of “Kaddish” ultimately resides in Ginsberg’s use of words as religious talismans, arranged with loving care through the mediation of his conscious thoughts and unconscious intuitions. Ginsberg himself died in April 1997. Diagnosed with advanced liver cancer and given just months to live, he informed the world that he had always expected to take such news in stride but was surprised that he actually felt ecstatic about it. He died peacefully and had a Buddhist funeral.

Gregory Corso was such a quintessential Beat that he was actually born in Greenwich Village, and his subsequent years provide a veritable grand tour of the Beat life. He came from a working-class family, unlike his Beat colleagues Kerouac, Burroughs, and Ginsberg. The Corsos were also a troubled family, and Corso spent much of his childhood in foster homes and institutions, including a reformatory and a children’s ward at Bellevue Hospital, where he was sent after a conviction for theft at the tender age of twelve. After that he lived largely on the New York streets, except while doing three years of hard time at an upstate prison from the age of seventeen to twenty. That is where he picked up a taste for literature, which stood him in good stead when he met Allen Ginsberg in a bar. Soon he was friendly with Kerouac and Burroughs, too.

Combining his need to earn a living with typical Beat wanderlust, Corso sold houses in Florida, wrote articles for the Examiner in Los Angeles, and put to sea on a Norwegian ship. He eventually settled in Cambridge, Massachusetts, sitting in on Harvard classes when the spirit moved him. By this time he had penned enough poetry to fill his first book, The Vestal Lady on Brattle and Other Poems, published in 1955. He then became acquainted with the San Francisco poetry scene, and visited Mexico City soon after. By the late 1950s his publications, readings, and outgoing personality had made him more of a public Beat icon than any of his peers except Ginsberg and Kerouac.

If any year can be called pivotal for Corso, it was 1958, when City Lights published his important collection Gasoline and his hotly debated poem “Bomb,” written in lines of different lengths that take the shape of an enormous mushroom cloud. That is also when he got addicted to heroin, which took a toll on his work over the next few years. Still, he traveled frequently to Europe in the late 1950s and early 1960s, and by 1965 he was at the State University of New York teaching about his favorite poet, the profoundly romantic Percy Bysshe Shelley.

Corso is remembered as a witty media figure—during the Beats’ heyday he was quoted and photographed everywhere from Time and Newsweek to Mademoiselle—and as the writer of two enduringly acclaimed poems, “Bomb” and “Marriage.” The first of them sparked controversy by being what nobody could have expected: serious and hilarious, scary and exuberant, sacred and profane, it dares to have fun with the onomatopoeia of the unthinkable (“BOMB O havoc antiphony molten cleft BOOM”) by mimicking the sound of nuclear pandemonium.

Corso was political to his bones, writing both negatively and positively about the character of the America he knew. But he was also irreverent to his bones, and at a time when the United States was investing in nuclear power as a way of life—and spawning a brave antinuclear movement to oppose it—the idea of mentioning nukes in the same breath as “binging bag” and “tee-hee finger-in-the-mouth hop” seemed scandalous to left-wingers who normally sympathized with Beat values. Conservatives and centrists also found it too frivolous and freewheeling for comfort. In sum, “Bomb” pleased nobody, and that pleased Corso.

“Marriage” appeared in Corso’s acclaimed 1960 collection The Happy Birthday of Death, and in 1989 it and “Bomb” were reprinted back-to-back in Mindfield, his final book. It is not hard to understand why “Marriage” became his most popular poem: it is one of the funniest verses by any Beat writer, vividly revealing the middle-class romantic lurking in Corso’s personality and playfully deconstructing it at the same time.

Corso was much loved by his Beat peers. Calling him an originator of the Beat literary movement, Ginsberg dubbed him “Captain Poetry” and described him as a “poetic wordslinger” and a “political philosophe.” And when critics complained about “grave flaws of character” in Corso, Burroughs retorted that poetry “is made from flaws” and that a “flawless poet is fit only to be a poet-laureate, officially dead and imperfectly embalmed. The stink of death leaks out.… I think that Gregory would survive even the laurel crown, for the smell of life would leak out.”

Corso died of cancer in 2001. His funeral was held at Our Lady of Pompei church in Greenwich Village, and his ashes were interred in Rome at the foot of Shelley’s grave. During his illness he “recovered from time to time,” according to his poet friend Robert Creeley, “saying that he’d got to the classic river but lacked the coin for Charon to carry him over. So he just dipped his toes in the water.” Fortunate is the poet who can retain such clarity of vision to the very end.

Burroughs’s fears about the post notwithstanding, Lawrence Ferlinghetti is one poet laureate who filled the position without being officially dead or imperfectly embalmed. In 1998 he became the first poet laureate appointed by San Francisco, his adopted city since the early 1950s.

Like so many of his Beat colleagues, Ferlinghetti had a troubled childhood. His father died before he was born, in a suburb of New York City in 1919, and his mother was institutionalized soon after. He lived in France with a relative for several years, then entered an American orphanage. His situation took a happier turn when wealthy friends of the family decided to help. From there on his history is one of extraordinary accomplishment. He even became an Eagle Scout during his teenage years at a private school in Massachusetts—although he also did a lot of hitchhiking and managed to get himself arrested on a minor charge.

Ferlinghetti entered the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in 1937, perhaps because his literary idol Thomas Wolfe had gone to college there. Then he shipped off to the U.S. Navy for a four-year stint, serving as an officer during World War II before returning to New York for a master’s degree at Columbia and a hearty taste of the Greenwich Village scene. He went back to Paris for two years in 1947, earning his doctorate at the Sorbonne. He had met the poet and translator Kenneth Rexroth in Paris, and after moving to San Francisco he became close to Rexroth and to the editor and sociologist Peter D. Martin, with whom he started City Lights Books in 1953. Two years later, on his own after Martin moved east, Ferlinghetti expanded City Lights into publishing as well as bookselling. When he started the Pocket Poets Series, it seemed appropriate to launch it his own collection Pictures of the Gone World. Volumes by Rexroth and Kenneth Patchen followed, and then Ginsberg’s groundbreaking Howl and Other Poems, which became a best seller (by poetry standards) with an assist from the censors who made it famous. Ferlinghetti has also been a painter, novelist, and journalist, as well as a friend to Zen seekers and anarchist thinkers.

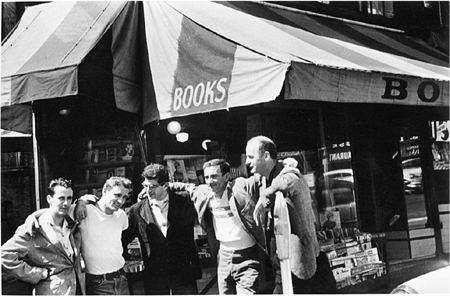

6. Allen Ginsberg (in dark jacket) and friends, including (aleft to right ) Bob Donlin, Neal Cassady, Robert LaVigne, and Lawrence Ferlinghetti, pose for Peter Orlovsky’s camera in front of Ferlinghetti’s legendary City Lights Books, which published many of the Beats’ most important works.

Ferlinghetti’s best-known book is the 1958 collection A Coney Island of the Mind, which combines reprinted poems from Pictures of the Gone World with new verses, including some (“Oral Messages”) specifically meant to be read aloud with jazz accompaniment. It takes only a handful of Ferlinghetti lines to convey his unique blend of free-flowing spirit and disciplined artistry, as in the invocation at the start of “I Am Waiting,” where he writes, “I am waiting for my case to come up and I am waiting / for a rebirth of wonder / and I am waiting for someone to really discover America.…” Few of the Beat writers did more than this poet, entrepreneur, and philosopher to make that discovery happen.

Neal Cassady was a Beat who did not write (much) but figured enormously in Beat life and lore. He grew up in a poor neighborhood of Denver, cared for (after a fashion) by his father, a nonfunctioning, often homeless alcoholic whom Kerouac and others described as a hobo and a bum. Neal became a hustler for money at an early age, and by his own account he stole more than five hundred cars before turning twenty-one.

Late in 1946, after one of his stretches in reform school, Cassady and his first wife (all of fifteen years old) boarded a bus for New York City to visit a Columbia student he knew. This friend introduced him to Ginsberg and to Kerouac, who later made him the model for Dean Moriarty in On the Road. Kerouac related well to this natural-born outsider who had grown up spending, like Dean in the novel, “a third of his time in the poolhall, a third in jail, and a third in the public library.” Kerouac said they “understood each other on levels of madness,” adding that Cassady’s intelligence “was every bit as formal and shining and complete” as that of Ginsberg and Burroughs, but was free of the “tedious intellectualness” he saw in his other friends.

Cassady’s first great Beat affection was for Ginsberg, who fell passionately in love with him—more passionately than Cassady felt comfortable with, for that matter. Kerouac grew jealous of their love affair even as he recognized that they were a compelling couple: “Two piercing eyes glanced into two piercing eyes—the holy conman [Cassady] with the shining mind, and the sorrowful poetic con-man [Ginsberg] with the dark mind,” to quote On the Road again. Ginsberg referred to the holy con-man many times in his work, including “Howl,” where Cassady is “N.C., secret hero of these poems, cocksman and Adonis of Denver.” The Fall of America contains an “Elegy for Neal Cassady,” and “The Green Automobile” centers on him.

Cassady’s influence on Kerouac operated on three levels. One was their friendship, which remained firm even though Kerouac regretted the fact that Cassady valued materialistic thrills at least as much as spiritual questing, however much Cassady may have chattered about religious ideas. Another was the companionship they shared while hitchhiking across the United States and into Mexico, having the nonstop adventures that On the Road so vividly depicts. A key theme in On the Road is Sal’s fascination with Dean as an embodiment of the Beat ideal—a fascination that borders on obsession—and the novel becomes something of a tragic love story when Sal realizes in the end that the Beat ideal is unattainable, turns away from Dean’s recklessness and sexual voracity, and opts for a less volatile, more conventional way of life. The third level was embodied by the “Great Sex Letter” and the “Joan Anderson Letter” that Cassady sent to Kerouac, affecting Kerouac’s prose style forevermore. Kerouac claimed that the Joan Anderson Letter was a whopping forty thousand words long, although it is impossible to verify that figure, because Ginsberg borrowed the missive and lent it to a friend in California, who lost it over the side of his houseboat. Kerouac called it “a whole short novel” and “the greatest piece of writing [he] ever saw.”

Cassady and Kerouac influenced and encouraged each other by turn. Cassady admonished his friend to “just write Jack, write! forget everything else,” and Kerouac exhorted his friend to “write only what kicks you and keeps you overtime awake from sheer mad joy.” From all accounts, it did not take much to keep either of them “overtime awake,” and Cassady appears to have outstripped Kerouac by a considerable margin when it came to manic adventurousness. He was indeed the “Holy Goof” whom Kerouac tried to capture in no fewer than six of his books, including two—On the Road and Visions of Cody—in which Cassady is the central figure and prime inspiration, standing for all of the spirit, adventurousness, and masculine cool that Kerouac wanted to emulate and embody in his own life.

Cassady’s anything-goes nature attracted extensive trouble as well as exciting kicks. He lost the Southern Pacific Railroad job that was helping him support his second wife, whom he married after getting his first marriage annulled; then he wedded a third wife while still married to the second, eventually returning to the second wife and the railroad job. More disastrously, he was arrested on a marijuana charge in 1958, landing in the San Quentin penitentiary for two years. It was after this incarceration that he met Ken Kesey, whose 1962 debut novel One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest had made a strong impression on him. Cassady became a member of—and bus driver for—the Merry Pranksters group, whose exploits were recorded by Tom Wolfe in The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, his 1968 book about psychedelic culture. Cassady reportedly tried introducing Kesey and Kerouac to each other at a New York party organized for that purpose, but the opportunity vanished when Kerouac, increasingly conservative as years went by, got miffed at someone’s irreverent treatment of an American flag.

Cassady never became a genuine Beat writer. His letters were legendary, and many of them have been published in book-length collections. He also completed a few chapters of an autobiography, The First Third, which impressed Ginsberg enough to say it “enlightened Buddha.” Ferlinghetti published it in 1971, after Cassady’s death. But that is about all Cassady wrote, despite the large amount that has been written about him, by various people including his second wife, Carolyn Cassady, whose book Off the Road recounts the twenty years of their relationship.

It is hard to say whether Cassady would have written more if he had lived beyond his early forties. Perhaps his potential would have been stifled by booze and drugs, as eventually happened in Kerouac’s case. Or maybe he would have mellowed into a productive writer with a huge store of madcap reminiscences to share. There were also serious ideas he was eager to discuss. “Away from us he didn’t stop talking about his spiritual beliefs,” wrote Carolyn Cassady, even though, she candidly adds, his actions often belied his words.

We will never know what Cassady might have become. After a dissolute night in the Mexican town of San Miguel de Allende, he embarked on a fifteen-mile walk to the next village along a deserted railway line. His only clothing was a T-shirt and a pair of jeans, and the combination of drugs, alcohol, and bad weather proved too much for him; he passed out next to the tracks and wasn’t found until morning. A few hours later he died in a hospital of exposure. In a short story about a character based on Cassady, the novelist and prankster Ken Kesey reinforces a Beat legend holding that Cassady was counting railroad ties as he walked, and that the last words he ever spoke were, “Sixty-four thousand nine hundred and twenty-eight.” Cassady was alone when he collapsed, however, so the legend’s truth or falsehood is something else we will never know. The surest thing about his hyperactive life is the influence it exerted on the Beats, the Merry Pranksters, and many others who crossed his path. Snyder caught the essence of this influence when he observed that “what got Kerouac and Ginsberg about Cassady was the energy of the archetypal West, the energy of the frontier, still coming down. Cassady is the cowboy crashing.”

John Clellan Holmes was born in 1926 to an aged-in-the-cask New England family. Among his close relatives were, by his own account, a “sentimentalist” father, a mother who took him to séances, and “a second cousin who could remember the date of William the Conqueror’s invasion but not always his own name.”

By his teenage years, Holmes was writing poetry and prose. Like some of his Beat friends, he found much reading time during World War II, serving in a Long Island hospital until he was discharged because of chronic migraine headaches. After his first marriage and a couple of years at Columbia, he began to get his poems published. At about the same time he met Kerouac and Ginsberg, and his 1952 essay “This Is the Beat Generation,” published in the New York Times, he provided the Beats with some of their first national attention and helped solidify the name of their loosely strung movement. Holmes wrote about Kerouac and Ginsberg with particular brilliance in the “Representative Men” section of Nothing More to Declare, his 1968 essay collection. His tag for Kerouac was “The Great Rememberer,” and for Ginsberg it was “The Consciousness Widener.”

Holmes also made Kerouac and Ginsberg important characters—along with Cassady, Huncke, and others—in his 1952 debut novel, Go, which he later described as “almost literal truth” about the early Beat years, drawn directly (except for pseudonymous names) from his day-to-day work journals. Among the book’s factual episodes, at least two are as strange and discomfiting as anything most authors could invent. In one, the character based on Kerouac learns that a publisher has accepted his first novel on the same day that the character based on Holmes finds out that his first novel has been rejected. In the other, Beats are shocked when an unruly friend (Bill Cannastra in real life) drunkenly enters a New York subway car, decides he wants one more drink back at the bar, tries to climb out a window, and immediately gets killed when the accelerating train pulls out of the station and into the narrow tunnel. These things actually happened, and Holmes recounts them sensitively through the words of Paul Hobbes, the slightly square narrator who represents the author.

Go was far from a best seller, but sale of the paperback rights brought Holmes a sizable amount of money. With his second wife he moved out of Beat-friendly New York City to a house in Old Saybrook, Connecticut, which became his permanent residence. There he worked on his second novel, The Horn, set in 1954 and published in 1958. Its hero is a Kansas City saxophone player named Edgar Pool, based on Lester Young and also Charlie Parker, whose death inspired the story’s last portion. Other characters are based on such jazz legends as Billie Holiday and Dizzy Gillespie; to make the novel’s texture more intricate, Holmes used additional musician characters to represent great American writers like Emily Dickinson and Edgar Allan Poe, fulfilling Kerouac’s idea of blurring the boundaries between music and literature. After returning to poetry as a main pursuit, Holmes finished one more novel, Get Home Free, published in 1964 but set, again, in the early 1950s. The main characters are a couple who do the kinds of things Beats did—living together in Greenwich Village, traveling to Europe, revisiting their hometowns, breaking up, and (ambiguously) making up at the end. In later years Holmes concentrated on poetry and essays as well as college teaching. He died of cancer in 1988.

For a while Holmes felt he was part of the Beat Generation tribe, but he later regarded himself as more an observer and chronicler than an actual member. His friendships with Kerouac and Ginsberg put him in the middle of the Beat scene during its formative years, and Kerouac made him a character in three of his novels—On the Road, Visions of Cody, and The Subterraneans—plus his Book of Dreams. Yet Kerouac appears to have viewed Holmes as a rival. In The Subterraneans, the Kerouac stand-in, Leo Percepied, describes the Holmes stand-in, Balliol MacJones, as “my arch literary enemy … erstwhile so close to me … we’d talked and exchanged and borrowed and read books and literarized so much the poor innocent had actually come under some kind of influence from me, that is, in the sense, only, that he learned the talk and style, mainly the history of the hip or beat generation or subterranean generation.” Percepied goes on to tell how he and the novel’s Ginsberg character, Adam Moorad, read MacJones’s first novel and were “critical of the manuscript.” Percepied adds that it earned MacJones a great deal of money when it was published, making him and Moorad decide that MacJones was “not of us—but from another world—the midtown sillies world.”

Kerouac apparently resented Holmes for capitalizing on his “influence,” and the resentment grew stronger when Holmes started writing The Horn, barging uninvited into jazzland, which Kerouac regarded as his privileged turf. Still and all, Kerouac put in a good word for the opening chapter of The Horn when Holmes submitted it to Discovery as a short story in 1953. Kerouac had many failings, but disloyalty wasn’t one of them.

Born in 1905, Kenneth Rexroth was about twenty years older than Kerouac and Ginsberg, and he was already an established San Francisco writer, translator, and pioneer of a new branch of avant-garde poetry well before the Beats came along. As master of ceremonies at the 6 Gallery reading, he played a considerable part in sparking the San Francisco Renaissance and propelling the original Beats to prominence. He also testified in Ginsberg’s defense at the obscenity trial that followed City Lights’ publication of Howl and Other Poems in 1956. All of this is ironic, since Rexroth eventually grew highly skeptical of the Beat group.

The immediate cause of his disillusionment was Kerouac’s mischievousness. Rexroth didn’t like Kerouac’s description of his tweedy appearance and “snide funny voice” in The Dharma Bums, and he liked it even less when Kerouac and friends went wild in his house not long after the 6 Gallery event. But there were deeper reasons why Rexroth was reluctant to be associated with the Beat group. For one thing, he was not fond of belonging to movements; he had joined the objectivist poets in the 1930s, then quickly left their company. For another, he was more interested than most Beats in experimental forms allied with surrealism and cubism in the visual arts. He was also more of a self-conscious intellectual than the average Beat, often crafting complex verse reflecting his prodigious knowledge in diverse fields from philosophy to Asian literature. And he was a strongly political person, committed to pacifism and ecological causes—interests shared by a Ginsberg and a Snyder but not by a Kerouac or a Burroughs.

It is unfortunate that Rexroth and the Beats did not maintain closer links because they had much in common. Rexroth hated conformity, loved nature, believed in poetry as an oral form, enjoyed reading his work with jazz accompaniments, saw love as the greatest human sacrament, immersed himself in Asian culture, and wrote Buddhist poetry in the years before his death in 1982. On a personal level, he had “fits of madness, temptations to suicide, the unstable temperament of a romantic poet,” according to the critic Morgan Gibson; yet on a public level he helped to “spread a counterculture throughout the world … challenging in poetry, prose, and speech the permanent war-mentality that has ominously clouded modern civilization.” Rexroth also had an energy that any Beat could envy—marrying four times, publishing almost sixty books, and living up to Beat poet David Meltzer’s description of him as an “anarchic libertarian Wild West magician sage.”

Rexroth could be blunt about Beat writing. He called Ginsberg’s early poem “Dream Record: June 8, 1955” a “stilted & somewhat academic” work, by Ginsberg’s own account, and he wrote that Kerouac’s sweeping Mexico City Blues was “more pitiful than ridiculous,” adding that it was “naïve effrontery” to publish such gobbledygook as poetry. But it was the Beat scene in general that ultimately turned him off. In an article on the San Francisco Renaissance, a Time magazine writer once labeled Rexroth the “father of the Beats,” to which he responded with a famous literary put-down: “An entomologist is not a bug.”

Nobody describes the work of Gary Snyder, lover of natural lore and master of the Zen spirit, better than he does himself. As he wrote in the 2005 preface to his collection Left Out in the Rain:

The primal & ancient Buddha, they say, is the only one in the entire universe of Buddha-forms who is unadorned.… Unadorned is sometimes a point for art, too. I have pushed poems to extremes of plainness, and have fancied the possibilities of writing superb poems that have absolutely no outstanding qualities. It is an intriguing ideal—but it is in fact just too difficult. Some of those efforts are in this collection. At the same time, one naturally plays around with form, wit, and complexity. Such poems are here too.

He goes on to list the varieties of verse in this single book as “both contentious and pretentious, plain meditations and linguistic wordplay, anti-haiku short poems, formal exercises, and critical statements.” Brought together, he adds, “I trust them in their diversity and I enjoy their weirdness.”

As one of the readers at the 6 Gallery evening, Snyder became a player in the emerging Beat scene, although he didn’t share the East Coast roots of the core Beats, having been born in San Francisco and raised in the Pacific Northwest region. Snyder’s fascination with nature and Native American life started in childhood, as did his love of books. After earning a degree in anthropology and literature, he started on graduate work along those lines, but his growing commitment to Zen Buddhism turned his focus to Oriental language and culture. He spent many of the years between 1956 and 1968 in Japan, studying Zen and working on translations.

These interests—the natural world, American Indian tribal life, Asian religious thought in general, and Zen thought in particular—have steadily informed Snyder’s life and poetry. His immersion in nature has also made him a strong environmentalist; he has written and lectured often on environmental issues in addition to exploring related themes in his poems. Kerouac made him the hero of The Dharma Bums, where Japhy Ryder radiates Zen enlightenment almost despite himself.

Snyder’s early books mark out the general directions that his work would take. Riprap, published in 1959, has a minimalist and introspective style, inviting the reader to participate in the poet’s everyday experiences. Myths & Texts, which appeared the next year, is a narrative poetry cycle drawing on a wide range of allusions and references that ultimately serve to portray myths and texts—roughly equivalent to unconscious and conscious, perhaps—as parts of a spiritually unified whole. Another key volume, The Back Country (1968), represents Snyder’s physical and metaphysical travels from the West Coast to Japan and India, and finally to the United States again. This book begins with “A Berry Feast,” which he read at the 6 Gallery, and ends with translations of the Japanese poet Miyazawa Kenji, whose sensibility Snyder finds similar to his own in some consequential respects.

Snyder has become an important figure in ecopoetics (nature poetry) and a major focus of discussion and study by practitioners of ecocriticism (environmentally geared literary criticism). The literary establishment has heaped many honors on him, from the Pulitzer Prize (1975) and the Bollingen Prize for Poetry (1997) to the John Hay Award for Nature Writing (1997), and he was the first American to receive the Buddhism Transmission Award (1998) from the Bukkyo Dendo Kyokai Foundation. It is possible that these prizes will not surpass the power of The Dharma Bums where Snyder’s lasting fame is concerned, but lasting fame appears to be the last thing on his mind.

The protean poet and playwright Amiri Baraka, who changed his name from LeRoi Jones in 1967, was a central personality in the overlapping bohemian circles of Greenwich Village in the late 1950s and early 1960s, where he was one of the very few—perhaps the only—African American writer in the group. He and his wife, Hettie Cohen, were coeditors of Yugen, a literary magazine (its name is a Japanese word connoting certain kinds of mystery and subtlety) that published Kerouac, Ginsberg, and other Beat figures. He also teamed with Diane di Prima to edit The Floating Bear, a little magazine that circulated poetry via the United States mail for several years starting in 1961; the issues were reprinted in 1973 as a 578-page volume called The Floating Bear: A Newsletter 1961–1969. Baraka completed his first poetry collection, Preface to a Twenty Volume Suicide Note, in 1961 and published the influential study Blues People: Negro Music in White America two years later. In 1964 his one-act play Dutchman, about the emotionally supercharged, ultimately fatal encounter of a white woman and a black man on a New York subway, won the prestigious Obie Award.

By the time Dutchman was written and produced, Baraka had become sharply critical of what he perceived as the apolitical, narcissistic nature of the Beat rebellion. After changing his name, he went through periods as a Black Nationalist, a radical socialist, and even poet laureate of New Jersey, a post he was fired from after writing “Somebody Blew Up America,” a poem suggesting that the September 11, 2001, attacks on U.S. targets were the work of conspirators from Israel and the George W. Bush administration; the poem goes so far as to suggest that thousands of Israeli workers stayed home from work that day because they were forewarned of the attacks. Baraka’s rhetorical excesses and disillusionment with the Beat movement notwithstanding, his challenges to prevailing social norms have never flagged, and he has continued to share the provocative spirit of the more politically minded Beats, among whom Ginsberg, Corso, and Ferlinghetti stand out.

The poet, fiction writer, photographer, painter, and political activist Diane di Prima was young enough (born in 1934) to be a disciple of the original Beats when she settled in Greenwich Village in the 1950s, but she became one of the most important women in the Beat movement. She knew from her teens that poetry was her vocation; “some of us speak,” she later wrote, “and that is a gift of the gods.” After meeting Kerouac, Ginsberg, and Baraka in New York, she moved to San Francisco and remained there, ultimately becoming the city’s poet laureate in 2009.

Di Prima’s biography reads like a catalog of exemplary Beat achievements. She got to know Ezra Pound in the 1950s, and around this time she struck up active correspondences with Ginsberg, Ferlinghetti, and other poets. She befriended Kerouac, Corso, Orlovsky, and their friends just as the Beats were poised for fame, and her debut poetry collection, This Kind of Bird Flies Backward, was published shortly afterward, in 1958. She draws on both spiritual and secular sources in her highly intuitive yet carefully crafted verse, which reflects the insights she has gathered from being the mother of five children as well as a feminist, an editor, and a Buddhist.

Di Prima was founder or cofounder of the Poets Institute, the Poets Press, and the New York Poets Theatre, and she edited the Floating Bear newsletter with Baraka during most of the 1960s. She was a member of Timothy Leary’s psychedelic community in upstate New York, collaborated with the Diggers in San Francisco, set up a poetics program at New College of California with Robert Duncan and David Meltzer, cofounded the San Francisco Institute of Magical and Healing Arts, and has taught at various other institutions. Along the way she studied Buddhism and alchemy, raised a family, and published dozens of books.

A hallmark of di Prima’s protean career as feminist, artist, and bohemian has been her ability to give feminine concerns a forceful, graceful voice within the male-dominated Beat scene. Her books, numbering more than forty, include such poetry volumes as The Book of Hours (1970), Loba: Books I & II (1998), and Revolutionary Letters (revised edition 2007) as well as the short-story collection Dinners and Nightmares (1961) and the autobiographical Memoirs of a Beatnik (1969) and Recollections of My Life as a Woman (2001). Few of the Beat writers have been more versatile or more prolific.

Ken Kesey assembled the Merry Pranksters who were immortalized in Tom Wolfe’s book The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, itself a key work of the New Journalism, which often had a Beat-like flavor in its first-person participatory prose. Kesey lived for a while in the North Beach neighborhood of San Francisco, beloved of Beats in the region, and discovered psychedelics when he volunteered as a guinea pig for drug experiments. The Pranksters were peripatetic, traveling across the United States in a psychedelically decorated bus. Neal Cassady was one of the first to drive Further, as the bus was called, and when they reached New York he introduced Kesey to his Beat friends there, although this was 1964 and Kesey felt the Beats were now passé. Kesey’s major work is the 1962 novel One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, tame in style but Beat-like in its negative view of authority.

Bob Kaufman drew less widespread attention than Baraka during the Beats’ heyday, but subsequent years have brought a steady increase in respect for his contributions as an African American Beat poet. Born in 1925 to a German Jewish father and a black Roman Catholic mother, Kaufman joined the Merchant Marine when he was barely in his teens and spent the next two decades traveling the world. Moving to Greenwich Village in the early 1940s, he studied literature briefly at the New School for Social Research, became friendly with Ginsberg and Burroughs, and moved with them to San Francisco, where he cultivated a wholly oral poetic style, composing verses meant to be recited and performed rather than written down and published. He was also a cofounder of Beatitude, a San Francisco magazine devoted primarily to promising young poets.

Drug addiction and trouble with the law afflicted Kaufman in the early 1960s, and after the assassination of President John F. Kennedy in 1963, which affected him deeply, he lived as a recluse for many years, under a Buddhist vow of silence. His reputation during his lifetime was higher in France and Britain than in the United States, but his surrealistic, bebop-inflected verse lives on in his collection The Ancient Rain: Poems 1956–1978 and a handful of other books that bear his name.

The poet and educator Anne Waldman was twenty to thirty years younger than the original Beats—a member of the next generation—so although she grew up in Greenwich Village she did not enter the Beat scene until the 1960s were half over. She quickly made up for lost time, forming strong friendships with everyone from Allen Ginsberg and Michael McClure to Robert Duncan and Lew Welch, among many others associated with the Beat group.

Interested in poetry and theater from an early age, in 1968 Waldman became director of the Poetry Project at St. Mark’s Church-in-the-Bowery, a venerable Manhattan church with a long history of progressive artistic experimentation. After discovering Buddhism in the early 1970s, thanks to guru Chogyam Trungpa, she incorporated elements of Buddhist breathing and chanting in her verse. One of her most valuable contributions came in 1974, when she and Ginsberg established the Jack Kerouac School for Disembodied Poetics at the Naropa Institute in Colorado.

7. Ten to twenty years younger than the original Beats, poet, performer, and educator Anne Waldman brings literary ingenuity and a fierce sense of cultural and political passion to her work. In another major contribution, she joined Allen Ginsberg to found the Jack Kerouac School for Disembodied Poetics at the Naropa Institute in Colorado in 1974.

As a poet, Waldman combines great accessibility and immediacy with an uncanny knack for moving from intensely personal concerns to evocations of the larger environment around her—as close as the light she is writing by, as far-flung as distant places on the globe—in the blink of an ingeniously turned phrase. She also has a fierce sense of cultural and political anger, which intersects in captivating ways with her Buddhist sensibility. As a performer, Waldman displays ferocious energy, chanting and howling her verse with an ecstatic passion that any shaman might admire. On both page and stage, she is one of the most powerful voices the Beat movement has produced. Describing her vocation in “Femanifesto” in 1994, Waldman wrote, “She—the practitioner—wishes to explore and dance with everything in the culture which is unsung, mute, and controversial.… She’ll challenge her fathers, her husband, male companions, spiritual teachers. Turn the language body upside down. What does it look like?” Her work offers invigorating answers to that question.