What is now called Behar was in former days the empire of Magadha. In the time of the Buddhists it was sacred territory, and is still covered with temples and monasteries. But, for many centuries, the Brahmins have occupied the place of the priests of Buddha. They have taken possession of the viharas or temples, and, turning them to their own account, live on the produce of the worship they teach. The faithful flock thither from all parts, and in these sacred places the Brahmins compete with the holy waters of the Ganges, the pilgrimages to Benares, the ceremonies of Juggernaut; in fact, one may say the country belongs to them.

The soil is rich, there are immense rice-fields of emerald green, and vast plantations of poppies. There are numerous villages, buried in luxuriant verdure, and shaded by palms, mangoes and date-trees, over which nature has thrown, like a net, a tangled web of creeping plants.

Steam House passed along roads which were embowered in foliage, and beneath the leafy arches the air was cool and fresh. We followed the chart of our route, and had no fear of losing our way.

The snorting and trumpeting of our elephant, mingled with the deafening screams of the winged tribes and the discordant chatterings and scoldings of apes and monkeys, and the golden fruit of the bananas, shone like stars through light clouds, as smoke and steam rolled in volumes among the trees. The delicate rice-birds rose in flocks as Behemoth passed along, their white plumage almost concealed as they flew through the spiral wreaths of steam.

Here and there the thick woods opened out into detached groups of banyans, groves of shaddocks, and beds of dahl (a sort of arborescent pea, which grows on stalks about a yard high), and glimpses were then obtained of landscapes in the background.

But the heat! the moist air scarcely made its way through the tatties of our windows. The hot winds, charged with caloric as they passed over the surface of the great western plains, enveloped the land in their fiery embrace.

One longs for the month of June, when this state of the atmosphere will be modified. Death threatens those who seek to brave the stroke of this flaming sun.

The fields are deserted. Even the ryots themselves, inured as they are to the burning heat, cannot continue their agricultural labours. The shady roadway alone is practicable, and even there we require the shelter of our travelling bungalow. Kâlouth the fireman must be made of pure carbon, or he would certainly dissolve before the grating of his furnace. But the brave Hindoo holds out nobly. It has become second nature with him, this existence on the platform of the locomotives which scour the railway lines of Central India!

During the daytime of May the 19th, the thermometer suspended on the wall of the dining-room registered 106 degrees Fahrenheit. That evening we were unable to take our accustomed “constitutional” or “hawakana.” This word signifies literally “to eat air,” and means that, after the stifling heat of the tropical day, people go out to inhale the cool pure air of evening. On this occasion we felt that, on the contrary, the air would eat us!

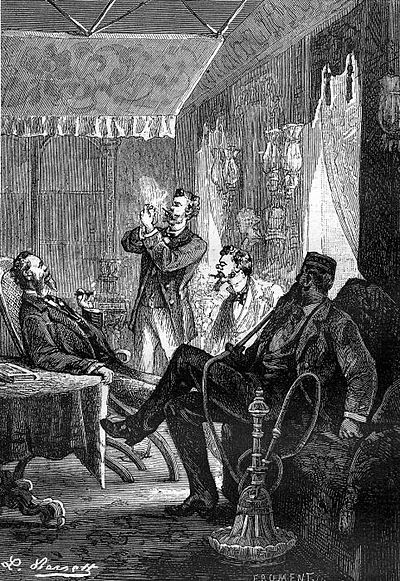

“Monsieur Maucler,” said Sergeant McNeil to me, “this heat reminds me of one day in March, when Sir Hugh Rose, with just two pieces of artillery, tried to storm the walls at Lucknow. It was sixteen days since we had crossed the river Bettwa, and during all that time our horses had not once been unsaddled. We were fighting between enormous walls of granite, and we might as well have been in a burning fiery furnace. The “chitsis” passed up and down our ranks, carrying water in their leathern bottles, which they poured on the mens’ heads as they stood to their guns, otherwise we should have dropped. Well do I remember how I felt! I was exhausted, my skull was ready to burst—I tottered. Colonel Munro saw me, and snatching the bottle from the hand of a chitsi, he emptied it over me—and it was the last water the carriers could procure…. A man can’t forget that sort of thing, sir! No, no! When I have shed the last drop of my blood for my colonel, I shall still be in his debt.”

“Sergeant McNeil,” said I, “does it not seem to you that since we left Calcutta, Colonel Munro has become more absent and melancholy than ever? I think that every day—”

“Yes, sir,” replied McNeil, hastily interrupting me, “but that is quite natural. My colonel is approaching Lucknow—Cawnpore—where Nana Sahib murdered…Ah, it drives me mad to speak of it! Perhaps it would have been better if this journey had been planned in some different direction—if we had avoided the provinces ravaged by the insurrection! The recollection of these awful events is not yet softened by time.”

“Why not even now change the route?” exclaimed I. “If you like, McNeil, I will speak about it to Mr. Banks and Captain Hood.”

“It’s too late now,” replied the sergeant. “Besides, I have reason to think that my colonel wishes to revisit, perhaps for the last time, the theatre of that horrible war; that he will once more go to the scene of Lady Munro’s death.”

“If you really think so, McNeil,” said I, “it will be better to let things take their course, and not attempt to alter our plans. It is often felt to be a consolation to weep at the grave of those who are dear to us.”

“Yes, at their grave!” cried McNeil. “But who can call the well of Cawnpore a grave? Could that fearful spot seem to anybody like a quiet grave in a Scotch churchyard, where, among flowers and under shady trees, they would stand on a spot, marked by a stone with one name, just one, upon it? Ah, sir, I fear the colonel’s grief will be something terrible! But I tell you again, it is too late to change the route. If we did, who knows but he might refuse to follow it? No, no; let things be, and may God direct us!”

It was evident, from the way in which McNeil spoke, that he well knew what was certain to influence his master’s plans, and I was by no means convinced that the opportunity of revisiting Cawnpore had not led the colonel to quit Calcutta. At all events, he now seemed attracted as by a magnet to the scene where that fatal tragedy had been enacted. To that force it would be necessary to yield.

I proceeded to ask the sergeant whether he himself had relinquished the idea of revenge—in other words, whether he believed Nana Sahib to be dead.

“No,” replied McNeil frankly. “Although I have no ground whatever for my belief, I feel persuaded that Nana Sahib will not die unpunished for his many crimes. No; I have heard nothing, I know nothing about him, but I am inwardly convinced it is so. Ah, sir! righteous vengeance is something to live for! Heaven grant that my presentiment is true, and then—some day—”

The sergeant left his sentence unfinished, but his looks were sufficient. The servant and the master were of one mind.

When I reported this conversation to Banks and the captain, they were both of opinion that no change of route ought to be made. It had never been proposed to go to Cawnpore; and, once across the Ganges at Benares, we intended to push directly northwards, traversing the eastern portion of the kingdoms of Oude and Rohilkund. McNeil might after all be wrong in supposing that Sir Edward Munro would wish to revisit Cawnpore; but if he proposed to do so, we determined to offer no opposition.

As to Nana Sahib, if there had been any truth in the report of his reappearance in the Bombay presidency, we ought by this time to have heard something more of him. But, on the contrary, all the intelligence we could gain on our route led to the conclusion that the authorities had been in error.

If Colonel Munro really had any ulterior design in making this journey, it might have seemed more natural that he should have confided his intentions to Banks, who was his most intimate friend, rather than to Sergeant McNeil. But the latter was no doubt preferred, because he would urge his master to undertake what Banks would probably consider perilous and imprudent enterprises.

At noon, on the 19th of May, we left the small town of Chittra, 280 miles from Calcutta. Next day, at nightfall, we arrived, after a day of fearful heat, in the neighbourhood of Gaya. The halt was made on the banks of a sacred river, the Phalgou, well known to pilgrims.

Our two houses were drawn up on a pretty bank, shaded by fine trees, within a couple of miles of the town. This place, being, as I mentioned before, extremely curious and interesting, we intended to remain in it for thirty-six hours, that is to say for two nights and a day. Starting about four o’clock next morning, in order to avoid the mid-day heat, Banks, Captain Hood, and I, left Colonel Munro, and took our way to the town of Gaya.

It is stated that 150,000 devotees annually visit this centre of Brahminical institutions; and we found every road to the place was swarming with men, women, old people, and children, who were advancing from all directions across the country, having braved the thousand fatigues of a long pilgrimage in order to fulfil their religious duties.

We could not have had a better guide than Banks, who knew the neighbourhood well, having previously been on a survey in Behar, where a railroad was proposed, but not yet constructed.

Captain Hood, who never liked to miss the chance of a shot, would have carried his gun; but Banks, lest our Nimrod should be tempted to wander away from us induced him to leave it in camp.

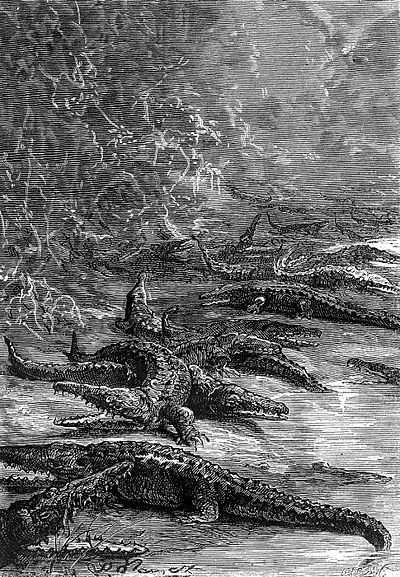

Just before entering the place, which is appropriately called the Holy City, Banks stopped us near a sacred tree, round which pilgrims of every age and sex were bowed in the attitude of adoration. This tree was a peepul: the girth of the trunk was enormous; but although many of its branches were decayed and fallen, it was not more than two or three hundred years old. This fact was ascertained by M. Louis Rousselet, two years later, during his interesting journey across the India of the Rajahs.

The “Tree of Buddha,” as it is called, is the last of a generation of sacred peepuls, which have for ages overshadowed the spot, the first having been planted there five centuries before the Christian era; and probably the fanatics kneeling before it believe this to be the original tree consecrated there by Buddha. It stands upon a ruined terrace close to a temple built of brick, and evidently of great antiquity.

The appearance of three Europeans, in the midst of these swarming thousands of natives, was not regarded favourably. Nothing was said, but we could not reach the terrace, nor penetrate within the old temple: certainly it would have been difficult to do so under any circumstances, on account of the dense masses of pilgrims by whom the way was blocked up.

“I wish we could fall in with a Brahmin,” said Banks; “we might then inspect the temple, and feel we were doing the thing thoroughly.”

“What!” cried I, “would a priest be less strict than his followers?”

“My dear Maucler,” answered Banks, “the strictest rules will give way before the offer of a few rupees! The Brahmins must live.”

“I don’t see why they should,” bluntly said Captain Hood, who never professed toleration towards the Hindoos, nor held in respect, as his countrymen generally do, their manners, customs, prejudices, and objects of veneration.

In his eyes India was nothing but a vast hunting ground, and he felt a far deeper interest in the wild inhabitants of the jungles than in the native population either of town or country.

After remaining for some time at the foot of the sacred tree, Banks led us on towards the town of Gaya, the crowd of pilgrims increasing as we advanced. Very soon, through a vista of verdure, the picturesque edifices of Gaya appeared on the summit of a rock.

It is the temple of Vishnu which attracts travellers to this place. The construction is modern, as it was rebuilt by the Queen of Holcar only a few years ago. The great curiosity of this temple are the marks left by Vishnu when he condescended to visit earth on purpose to contend with the demon Maya. The struggle between a god and a fiend could not long remain doubtful.

Maya succumbed, and a block of stone, visible within the enclosure of Vishnu-Pad, bears witness, by the deep impress of his adversary’s foot-prints, that the demon had to deal with a formidable foe.

I said the block of stone was “visible;” I ought to have said “visible to Hindoo natives only.” No European is permitted to gaze upon these divine relics.

Perhaps a more robust faith than is to be found in Western minds may be necessary in order to distinguish these traces on the miraculous stone. Be that as it may, Bank’s offer of money failed this time. No priest would accept what would have been the price of a sacrilege; I dare not venture to suppose that the sum offered was unequal to the extent of the Brahminical conscience. Anyhow, we could not get into the temple dedicated to that gentle good-looking young man of azure-blue colour, attired and crowned like a king of ancient times, and celebrated for his ten incarnations, who represents the “Preserver,” as opposed to Siva, the ferocious “Destroyer,” and is acknowledged by the Vaishnavas (or worshippers of Vishnu) to be chief among the three hundred and thirty million deities of this pre-eminently polytheistic mythology.

But we had no reason to regret our excursion to the Sacred City, nor to the Vishnu-Pad. It would be utterly impossible to describe the confused mass of temples and the endless succession of courts which we traversed. Theseus himself, with Ariadne’s thread in his hand, would have been lost in such a labyrinth, and after all we were refused admittance to the sanctuary! We finally descended the rocky eminence of Gaya.

Captain Hood was furious. He seemed disposed to deal summarily with the Brahmin who had turned us away.

Banks had to restrain him forcibly.

“Are you mad, Hood?” said he. “Don’t you know that the Hindoos regard their priests, the Brahmins, not merely as a race of illustrious descent, but also as beings of altogether superior and supernatural origin?”

When we reached that part of the river Phalgou which bathes the rock of Gaya, the prodigious assemblage of pilgrims lay before us in its full extent. There, in indescribable confusion, was a heaving, huddling, jostling crowd of men and women, old men and children, citizens and peasants, rich baboos and poor ryots, of every imaginable degree; “Vaichyas,” merchants and husbandmen, “Kchatryas,” haughty native warriors; “Sudras,” wretched artisans of different sorts; “Pariahs,” beneath and outside all caste, whose very eyes defile the objects they look upon; in a word all classes and every caste in India. The vigorous, high-spirited Rajpoot elbowing the weak Bengalee, the natives of the Punjaub face to face with those of Scinde. Some came in palanquins, others in carriages drawn by large humped oxen. Some lie beside their camels, whose snakelike heads are stretched out on the ground, while many travel on foot from all parts of India. Here tents are set up; there carts and waggons are unyoked, and numerous huts made of branches are prepared as temporary shelter for the crowd.

“What a mob!” exclaimed Captain Hood.

“The water of the Phalgou will not be fit to drink this evening,” observed Banks.

“Why not?” inquired I.

“Because its waters are sacred, and this unsavoury crowd will go and bathe in them, as they do in the Ganges.”

“Are we down stream?” cried Hood, pointing towards our encampment.

“No! don’t be uneasy, captain!” answered Banks laughing; “we are up the river.”

“That’s all right! It would never do to water Behemoth at an impure fountain!”

We passed on through thousands of natives massed together in comparatively small space. The ear was struck by a discordant noise of chains and small bells. It was thus that mendicants appealed to public charity. Infinitely varied specimens of this vagrant brotherhood swarmed in all directions. Most of them displayed false wounds and deformities, but although the professed beggars only pretend to be sufferers, it is very different with the religious fanatics. In fact it would be difficult to carry enthusiasm further than they do.

Some of the fakirs, nearly naked, were covered with ashes; one had his arm fixed in a painful position by prolonged tension, another had kept his hand closed until it was pierced by the nails of his own fingers.

Some had measured the whole distance of their journey by the length of their bodies. For hundreds of miles they had continued incessantly to lie down, rise up, and lie down again, as though acting the part of a surveyor’s chain.

Here some of the faithful, stupefied with “bang” (which is liquid opium mixed with a decoction of hemp), were suspended on branches of trees, by iron hooks plunged into their shoulders. Hanging thus, they whirled round and round until the flesh gave way, and they fell into the waters of the Phalgou.

Others, in honour of Siva, had pierced their arms, legs, or tongues through and through with little darts, and made serpents lick the blood which flowed from the wounds.

Such a spectacle could not be otherwise than repugnant to a European eye. I was passing on in haste, when Banks suddenly stopped me, saying,—“The hour of prayer!”

At the same instant a Brahmin appeared in the midst of the crowd. He raised his right hand, and pointed towards the rising sun, hitherto concealed behind the rocks of Gaya.

The first ray darted by the glorious luminary was the signal. The all but naked crowd entered the sacred waters. There were simple immersions, as in the early form of baptism, but these soon changed into water parties of which it was not easy to perceive the religious character. Perhaps the initiated, who recited “slocas” or texts, which for a given sum the priests dictated to them, thought no more of the cleansing of their bodies than their souls. The truth being that after having taken a little water in the hollow of the hand, and sprinkled it towards the four cardinal points, they merely threw up a few drops into their faces, like bathers who amuse themselves on the beach as they enter the shallow waves. I ought to add besides, that they never forgot to pull out at least one hair for every sin they had committed. A good many deserved to come forth bald from the waters of the Phalgou!

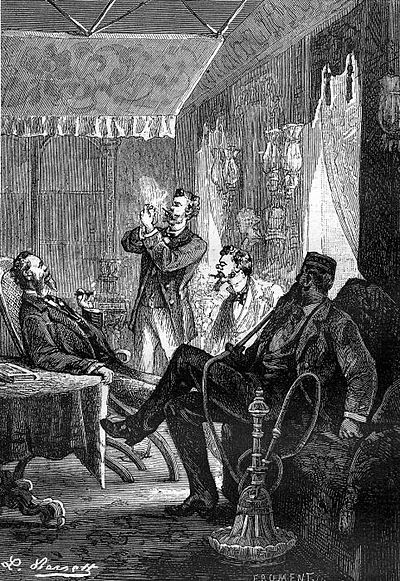

So vehement were the watery gambols of the faithful, as they plunged hither and thither, that the alligators in terror fled to the opposite bank. There they remained in a row, staring with their dull sea-green eyes at the noisy crowd which had invaded their domain, and making the air resound with the snapping of their formidable jaws. The pilgrims paid no more attention to them than if they had been harmless lizards.

It was time to leave these singular devotees, who were getting ready to enter Ka’flas, which is the paradise of Brahm; so we went up the river and returned to our encampment.

Breakfast awaited us; and the rest of the day, which was excessively hot, passed without incident.

Towards the evening Captain Hood went out shooting, and brought in some game.

Meantime, as we were to start at daybreak, Storr, Kâlouth, and Goûmi, took in supplies of wood and water, and made all necessary preparations. By nine in the evening we had retired to our bedrooms. The night was likely to be very calm but dark, for thick clouds obscured the stars, and made the atmosphere so heavy, that the heat continued as great as before sunset.

I found it difficult to fall asleep in temperature so stifling; my window was open, but the hot air which entered, seemed to me very unfit for the use of human lungs.

Midnight came, and I had not enjoyed an instant’s repose. I was firmly resolved to sleep for two or three hours before our departure; but I made a mistake in supposing I could command the visit of slumber. The more I exerted my will in the effort, the further slumber fled from me, utterly refusing to obey the summons.

It might have been one o’clock in the morning when I thought I heard a dull murmuring sound approach along the banks of the Phalgou.

My first idea was, that the atmosphere being charged with electricity, a storm of wind was rising in the west which would displace the strata of air, and perhaps make it more suitable for respiration. I was mistaken; the branches of the trees above us remained motionless; not a leaf stirred.

I put my head out at my window and listened. I plainly heard the distant murmur, but nothing was to be seen. The surface of the river was calm and placid, and the sound proceeded neither from the air nor from the water. Although puzzled, I could perceive no cause for alarm, and returning to bed, fatigue overcame my wakefulness, and I became drowsy. At intervals I was conscious of the inexplicable murmuring noise, but finally fell fast asleep.

In about two hours, just as the first rays of dawn broke through the darkness, I awoke with a start. Some one in the passage was calling the engineer. “Mr. Banks!”

“What is wanted?”

“Will you come here, sir?”

It was Storr the fireman who spoke to Banks. I rose immediately, and joined them in the front verandah. Colonel Munro was already there, and Captain Hood came soon after. “What’s the matter?” I heard Banks say.

“Just you look, sir,” replied Storr.

It was light enough for us to see the river banks, and part of the road which stretched away before us; and to our great surprise these were encumbered by several hundred Hindoos, who were lying about in groups.

“Ah! those are some of the pilgrims we saw yesterday!” said Captain Hood.

“But what are they doing here?” said I.

“No doubt,” replied the captain, “they are waiting for sunrise, that they may perform their ablutions.”

“No such thing,” said Banks; “why should they leave Gaya to do that? I suspect they have come here because—”

“Because Behemoth has produced his usual effect,” interrupted Captain Hood. They heard that a huge great elephant—a colossus—bigger than the biggest they ever saw, was in the neighbourhood, and of course they came to admire him.”

“If they keep to admiration, it will be all very well,” returned the engineer, shaking his head.

“What do you fear, Banks?” asked Colonel Munro.

“Well, I am afraid these fanatics may get in the way, and impede our progress.”

“Be prudent, whatever you do! One cannot act too cautiously in dealing with such devotees.”

“Kâlouth!” cried Banks, calling the stoker, “are the fires ready?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Well, light up.”

“Yes, light up by all means, Kâlouth,” cried Captain Hood; “blaze away, Kâlouth; and let Behemoth puff smoke and steam into the ugly faces of all this rabble!”

It was then half-past three in the morning. It would take half-an-hour to get up steam. The fires were instantly lighted. The wood crackled in the furnaces and dense smoke issued from the gigantic trunk of the elephant, which was uplifted high among the boughs of the great trees.

Several parties of natives approached; then a general movement took place in the crowd. The people pressed closer round us. Those in the foremost rank threw up their arms in the air, stretched them towards the elephant, bowed down, knelt, cast themselves prostrate on the ground, and distinctly manifested the most profound adoration.

There we stood beneath the verandah, very anxious to know what this display of fanaticism would lead to. McNeil joined us, and looked on in silence. Banks took his place with Storr in the howdah, from which he could direct every movement of Behemoth.

By four o’clock steam was up. The noise made by the engine was, of course, taken by the Hindoos for the angry trumpeting of an elephant belonging to a supernatural race. Storr allowed the steam to escape by the valves, and it appeared to issue from the sides, and through the skin of the gigantic quadruped.

“We are at high pressure.”

“Go ahead, Banks,” returned the colonel; “but be careful; don’t let us crush anybody.”

It was almost day. The road along the river bank was occupied by this great crowd of devotees, who seemed to have no idea of making way for us, so that to go forward and crush no one was anything but easy. The steamwhistle gave forth two or three short piercing shrieks, to which the pilgrims replied by frantic howls.

“Clear the way there!” shouted the engineer, telling the stoker at the same time to open the regulator. The steam bellowed as it rushed into the cylinders; the wheels made half a revolution, and a huge jet of white smoke issued from the trunk.

For an instant the crowd swerved aside. The regulator was then half open; the trumpeting and snorting of Behemoth increased in vehemence, and our train began to advance between the serried ranks of the natives, who seemed loth to give place to it.

“Look out, Banks!” I suddenly exclaimed.

I was leaning over the verandah rails, and I beheld a dozen of these fanatics cast themselves on the road, with the evident wish to be crushed beneath the wheels of the monstrous machine.

“Stand back there! Attention!” shouted Colonel Munro, signing to them to rise.

“Oh, the idiots!” cried Captain Hood; “they take us for the car of Juggernaut! They want to get pounded beneath the feet of the sacred elephant!”

At a sign from Banks, the fireman shut off steam. The pilgrims, lying across the road, seemed desirous not to move. The fanatic crowd around them uttered loud cries, and appeared by their gestures to encourage them to persevere. The engine was at a standstill. Banks was excessively embarrassed.

All at once an idea struck him.

“Now we shall see!” he cried; and turning the tap of the clearance pipes under the boiler, strong jets of steam issued forth, and spread along the surface of the ground; while the air was filled by the shrill, harsh screams of the whistle.

“Hurrah! hurrah!” shouted Captain Hood. “Give it them, Banks! give it them well!”

The method proved successful. As the streams of vapour reached the fanatics, they sprang up with loud cries of pain. They were prepared and anxious to be run over, but not to be scalded.

The crowd drew back. The way was clear. Steam was put on in good earnest, and the wheels revolved steadily.

“Forward!” exclaimed Captain Hood, clapping his hands and laughing heartily.

And at a rapid rate Behemoth took his way along the road, vanishing in a cloud of vapour, like some mysterious visitant, from before the eyes of the wondering crowd.