At eleven o’clock we returned to the encampment, anxious to leave Cawnpore as quickly as possible; but our engine required some trifling repairs, and it was impossible to do so before the following morning.

Part of a day, then, was at my disposal. I considered that I could not employ it better than by visiting Lucknow, as Banks did not intend to pass through that place, where Colonel Munro would again have been brought in contact with reminiscences of the war. He was right. These vivid recollections were already far too poignant.

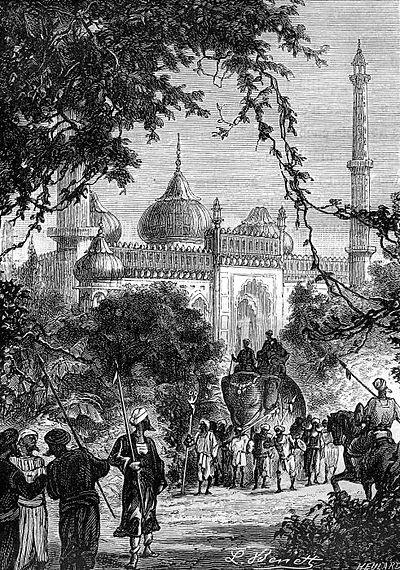

At mid-day, then, quitting Steam House, I took the little branch railway which unites Cawnpore to Lucknow. The distance is not more than twenty leagues, and in a couple of hours I found myself in this important capital of the kingdom of Oude, of which I wished merely to obtain a glance, or, as I might say, an impression. I soon perceived the truth of what I had heard respecting the great buildings of Lucknow, built during the reigns of the Mohammedan emperors of the seventeenth century.

A Frenchman, named Martin, a native of Lyons, and a common soldier in the army of Lally-Tollendal, became, in 1730, a favourite with the king. He it was who designed, and in fact may be called the architect of the so-called marvels of the capital of Oude.

The Kaiser Bagh, or official residence of the sovereigns, is a whimsical and fantastic medley of every style of architecture which could possibly emanate from the imagination of a corporal, and is a most superficial structure. The interior is nothing; all the labour has been lavished on the outside, which is at once Hindoo, Chinese, Moorish, and…European. It is the same with regard to another smaller palace, called the Farid Bakch, which is likewise the work of Martin.

As to the Imâmbara, built in the midst of the fortress by Kaifiatoulla, the greatest architect of India in the seventeenth century, it is really superb, and, bristling with its hundreds of bell-towers, has a grand and imposing effect!

I could not leave Lucknow without seeing the Constantine Palace, which is another of the original performances of the French corporal, and bears his name. I also wished to visit the adjacent garden, called Secunder Bagh, where hundreds of sepoys were executed for having violated the tomb of the humble soldier of fortune before they abandoned the town.

Another French name besides that of Martin is honoured at Lucknow. A non-commissioned officer, formerly of the “Chasseurs d’Afrique,” named Duprat, so distinguished himself by his bravery during the mutiny, that the rebels offered to make him their leader. Duprat nobly refused, notwithstanding the promises of wealth held out to tempt him, and the threats with which he was menaced when he stood firm. He remained faithful to the English. But the sepoys, who had failed to make him a traitor, directed against him their special vengeance, and he was slain in an encounter. “Infidel dog!” they had said on his refusal to join them, “we will have thee in spite of thyself!” And they had him; but only when he was dead!

The names of these two French soldiers were united in the reprisals: for the sepoys who had insulted the tomb of the one, and prepared the grave of the other, were ruthlessly put to death!

At length—having admired the magnificent parks which encircle this great city of 500,000 inhabitants as with a belt of verdure and flowers, and having ridden on elephant-back through the principal streets, and the fine boulevard of Hazrat Gaudj—I took the train, and returned to Cawnpore.

Next morning, the 31st of May, we resumed our route.

“Now then!” cried Captain Hood; “we are done at last with your Allahabads, your Cawnpores, Lucknows, and the rest, for which I care about as much as I do for a blank cartridge!”

“Yes, Hood, we have got through all that,” replied Banks; “and now for the north, towards which we are to travel almost in a direct line, to the base of the Himalayas.”

“Bravo!” resumed the captain. “What I call real India is not the provinces, crammed with native towns and swarming with people, but the region where live in freedom my friends the elephants, lions, tigers, panthers, leopards, bears, bisons, and serpents. That is, in reality, the only habitable part of the whole peninsula! You will see that it is so, Maucler, and you will have no reason to regret the valley of the Ganges!”

“In your society I can regret nothing, my friend,” replied I.

“There are, however,” said Banks, “some very interesting towns in the north-west; such as Delhi, Agra, and Lahore…”

“Oh! my dear fellow! who ever heard of those miserable little places!” cried Hood.

“Miserable, indeed!” replied Banks. “Let me tell you, Hood, they are magnificent cities! And,” he continued, turning to me, “we must manage to let you see them, Maucler, without throwing out the captain’s plans for a sporting campaign.”

“All right, Banks,” said Hood; “but it is only from to-day that I consider our journey to have fairly commenced.”

Presently, in a loud voice, he shouted, “Fox!”

“Here, captain!” answered his servant.

“Fox! get all the guns, rifles, and revolvers in good order!”

“They are so, sir.”

“Prepare the cartridges.”

“They are prepared.”

“Is everything ready?”

“Quite ready, sir.”

“Make everything still more ready.”

“I will, sir.”

“It won’t be long before the thirty-eighth takes his place on your glorious list, Fox!”

“The thirty-eighth!” cried the man, with sudden light in his eye; “he won’t have to complain of the nice little ball I am keeping ready for him!”

“Get along with you, Fox!”

With a military salute Fox faced about, and re-entered the gun-room.

I will now give an outline of the plan for the second part of our journey—a plan which only unforeseen events were to induce us to alter.

By this route we were to ascend the course of the Ganges towards the north-west for a long way, and then, turning sharp to the north, continue our way between two rivers; one a tributary of the great river, the other of the Goûmi. By this means a considerable number of streams would be avoided; and, passing by Biswah, we should rise in an oblique direction to the lower ranges of the mountains of Nepaul across the western part of Oude and Rohilkund.

This route had been ingeniously planned by Banks, so as to surmount all difficulties. If coal were to fail in the north of Hindoostan, we were sure of having abundance of wood, and Behemoth would easily keep up any rate of speed we wished, on good roads through the grandest forests of the Indian peninsula.

It was agreed that we might easily reach Biswah in six days, allowing for stoppages at convenient places, and time for the sportsmen of the party to exhibit their prowess. Besides, Captain Hood, with Fox and Goûmi, could easily explore the vicinity of the roads, while Behemoth moved slowly along.

I was permitted to join them, although I was far from being an experienced hunter, and I occasionally did so.

I ought to mention that from the moment our journey took this new aspect, Colonel Munro became more sociable. Once fairly among the plains and forests beyond the valley of the Ganges, he appeared to resume the calm and even tenor of the life he used to lead at Calcutta, although it was impossible to suppose he could forget that we were gradually approaching the north of India, the region whither he was attracted as by an irresistible fatality. His conversation became more animated, both at meals and during the pleasant evening hours when we halted. As for McNeil, he seemed more gloomy than usual. Had the sight of Bibi-Ghar revived his hatred and thirst for vengeance?

“Nana Sahib killed?” said he to me one day. “No, no, sir; they have not done that for us yet!”

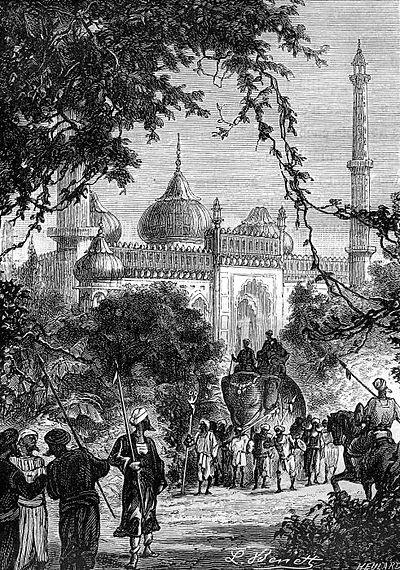

The first day of our journey passed without any incident worth recording. Neither Captain Hood nor Fox had a chance of aiming at any sort of animal. It was quite distressing, and so extraordinary that we began to wonder whether the apparition of a steam elephant could be keeping the savage dwellers of the plains at a distance. We passed several jungles, known to be the resort of tigers and other carnivorous feline creatures. Not one showed himself, although the hunters kept away full two miles from us.

They were forced to devote their energies, with Niger and Fan, to shooting for Monsieur Parazard’s larder. He expected to be supplied regularly, and considered game for the table of paramount importance, most unreasonably despising the tigers and other beasts Fox talked to him about.

Disdainfully shrugging his shoulders he would ask, “Are they good to eat?”

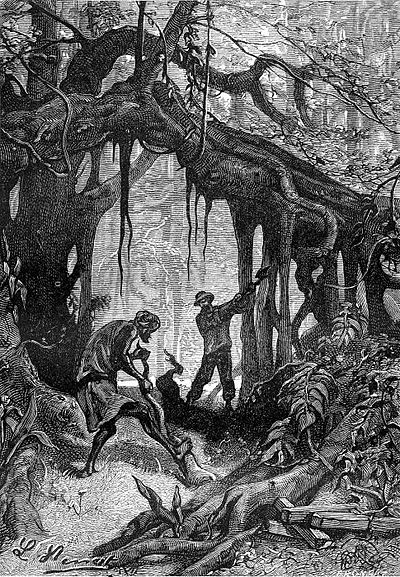

In the evening we fixed our camp beneath the shelter of a group of enormous banyans. The night was as tranquil as the day had been calm. No roars or howlings of wild animals broke the silence. The snorting of Behemoth himself was stilled.

When the camp-fires were extinguished, Banks, to please the captain, refrained from connecting the electric current by which the elephant’s eyes would have become two powerful lamps. But nothing came of it. It was the same the two following nights. Hood was getting desperate.

“What can have happened to my kingdom of Oude?” repeated the captain. “It has been translated! There are no more tigers here than in the lowlands of Scotland!”

“Perhaps there may have been battues here lately,” suggested Colonel Munro. “The animals may have emigrated en masse. But cheer up, my friend, and wait till we reach the foot of the mountains of Nepaul. You will find scope for your hunting instincts there!”

“It is devoutly to be hoped it may be so, colonel,” replied Hood, sadly shaking his head. “Otherwise we may as well re-cast our balls, and make small shot of Ethan!”

The 3rd of June was one of the hottest days which we had endured. There was not a breath of wind, and had not the road been shaded by huge trees, I think we must have been literally baked in our rooms. It seemed possible that, in heat like this, wild animals did not care to quit their dens even during the night.

Next morning, at sunrise, the horizon to the westward for the first time appeared somewhat misty. We then had presented to our eyes a magnificent spectacle—the phenomenon of the mirage, which is called in some parts of India seekote, or castles in the air; and in others dessasur or illusion.

What we saw was not a visionary sheet of water, with curious effects of refraction, but a complete chain of low hills, crowned by castles of the most fantastic form, resembling the rocky heights of some Rhenish valley with their ancient fastnesses of the Margraves. In a moment we seemed transported not only to that romantic part of Europe, but into the Middle Ages five or six centuries back. This phenomenon was surprisingly clear, and gave us a strange sensation of absolute reality. So much so, that the gigantic elephant-engine, with all its apparatus of modern machinery, advancing towards the habitations of men of Europe, in the eleventh century, struck us as far more out of place and unnatural than when traversing, beneath clouds of vapour, the country of Vishnu and Brahma.

“We thank you, fair Lady Nature!” cried Captain Hood; “instead of the minarets and cupolas, mosques and pagodas, we have been accustomed to, you are spreading before us charming old towns and castles of feudal times!”

“How poetical you are this morning, Hood!” returned Banks. “Pray have you been reading romantic ballads lately?”

“Laugh away, Banks; quiz me as much as you like, but just look there! See how objects in the foreground are growing in size! The bushes are turning into trees, the hills into mountains, the—”

“Why the very cats will be tigers soon, won’t they, Hood?”

“Ah, Banks! how jolly that would be…There!” continued the captain, “my Rhenish castles are melting away; the town is crumbling to ruins, and we return to realities, seeing only a landscape in the kingdom of Oude, which the very wild animals have deserted.”

The sun, rising above the eastern horizon, quickly dissipated the magical effects of refraction. The fortresses, like castles built of cards, sank down with the hills, which were suddenly transformed into plains.

“Well, now that the mirage has vanished, and with it Hood’s poetic vein, shall I tell you, my friends,” said Banks, “what the phenomenon presages?”

“Say on, great engineer!” quoth the captain.

“Nothing less than a great change of weather,” replied Banks. The early days of June are usually marked by climacteric changes. The turn of the monsoon will bring the periodical rainy season.”

“My dear Banks,” said I, “let it rain as it will, we are snug enough here. Under cover like this I should prefer a deluge to heat such as—”

“All right, my dear friend, you shall be satisfied,” returned he; “I believe the rain is not far off, and we shall soon see the first clouds in the south-west.”

Banks was right. Towards evening the western horizon became obscured by vapours, showing that the monsoon, as frequently happens, would commence during the night. These mists, charged with electricity, came across the peninsula from the Indian Ocean, like so many vast leathern bottles out of the cellars of Eolus, filled full of storm, tempest, and hurricane.

Other signs, well-known to Anglo-Indians, were observed during the day. Spiral columns of very fine dust whirled along the roads, in a manner quite unlike that which was raised by our heavy wheels. They resembled a number of those tufts of downy wool which can be set in motion by an electrical machine. The ground might, therefore, be compared to an immense receiver in which for several days electricity had been stored up. This dust was strangely tinted with yellow, and had a most curious effect, each atom seeming to shine from a little luminous centre. At times we appeared to be travelling through flames, harmless flames, it is true, though neither in colour nor vivacity resembling the ignis fatims.

Storr told us that he had sometimes seen trains pass along the rails between a double hedge of this luminous dust, and his statement was confirmed by Banks. During a quarter of an hour I watched very carefully this singular phenomenon from the windows of the turret on the engine, whence I could look along the route we were following for a considerable distance. There were no trees by the road, which was thickly covered with dust, intensely heated by the vertical rays of the sun. The burning heat of the atmosphere appeared to me just then to surpass that of our furnaces. It was insupportable, and, almost suffocated, I withdrew to breathe fresher air beneath the fanning wings of the punkah.

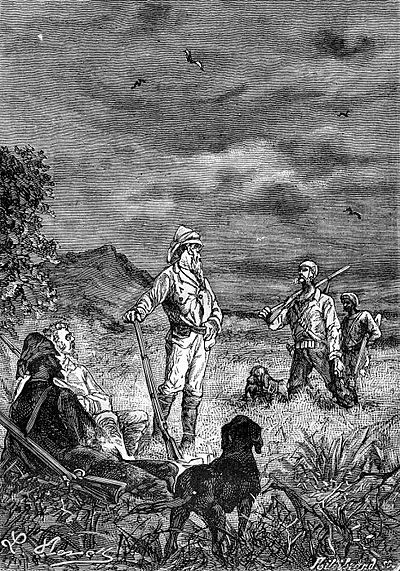

At about seven o’clock in the evening our train came to a halt. The place chosen by Banks was on the borders of a forest of magnificent banyans whose shade appeared to stretch northward to an infinite distance. A good road passed through this forest, and we promised ourselves a pleasanter journey next day beneath these wide and lofty domes of verdure.

The banyans, those giants of the Indian forest, stand surrounded by their children and grandchildren like patriarchs of the vegetable world. The young trees, springing from one common root, rise up around the main trunk, but completely detached from it, and mingle their branches with the towering verdure of the paternal stem. They give one the idea of having been hatched under this dense foliage, like chickens beneath their mother’s wings. Hence the singular aspect of these venerable forests which have for age after age continued in this way to extend their limits. The old banyans resemble isolated pillars supporting an enormous vault, the finer arches and mouldings of which rest on the younger trees, they in their turn becoming main pillars.

On this evening the encampment was arranged with greater care than usual, because if the heat of the following day should prove equally overpowering, Banks proposed to prolong the halt, so as to pursue the journey during the night.

Colonel Munro was well pleased to think of spending some hours in this noble forest, so shady, so deeply calm. Everybody was satisfied with the arrangement; some because they really required rest, others because they longed once more to endeavour to fall in with some animal worth firing at. It is easy to guess who those persons were.

“Fox! Goûmi! it is only seven o’clock!” cried Captain Hood as soon as we came to a halt; “let’s take a turn in the forest before it is quite dark. Will you come with us, Maucler?”

“My dear Hood,” said Banks, before I had time to answer, “you had better not leave the encampment. The weather looks threatening. Should the storm burst, you would find some trouble in getting back to us. To-morrow if we remain here, you can go.”

“But to-morrow it will be daylight again,” replied Hood. “The dark hours are what I want for adventure!”

“I know that, Hood, but the night which is coming on is very unpromising. Still, if you are resolved to go, do not wander to any distance. In an hour, it will be very dark, and you might have great difficulty in making your way back to camp.”

“Don’t be uneasy, Banks; it is hardly seven o’clock, and I will only ask the colonel for leave of absence till ten.”

“Go, if you wish it, my dear Hood,” said Sir Edward “but pray attend to the advice Banks has given you.”

“All right, colonel.” And the captain, with his followers Fox and Goûmi, all well equipped for the chase, left the encampment, and quickly disappeared behind the thick trees.

Fatigued by the heat of the day, I remained in camp.

Banks gave orders that the engine fires should not, as they usually were, be completely extinguished. He wished to retain the power of quickly getting up steam in case of an emergency.

Storr and Kâlouth betook themselves to their accustomed tasks, and attended to the supplies of wood and water; in doing so, they found little difficulty, for a small stream flowed near our halting-place, and there was no lack of timber close at hand. M. Parazard diligently laboured in his vocation, and, while putting aside the remains of one dinner, was busily planning the next.

As the evening continued pleasant, Sir Edward, Banks, McNeil, and I, went to rest by the borders of the rivulet, as the flow of its limpid waters refreshed the atmosphere, which even at this hour was suffocating.

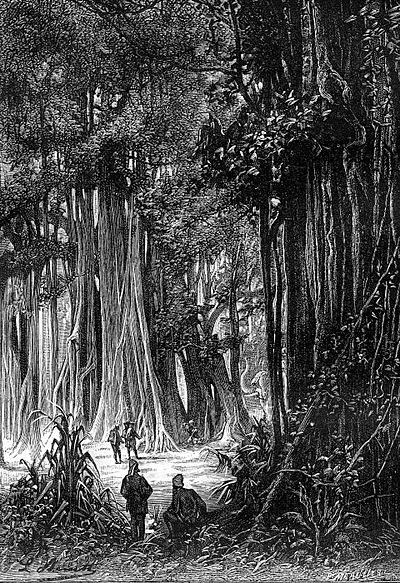

The sinking sun shed a light which tinged with a colour like dark blue ink a mass of vapour which through openings in the dense foliage we could see accumulating in the zenith. These thick, heavily condensed clouds were stirred by no wind, but appeared to advance with a solemn motion of their own.

We remained chatting here till about eight o’clock. From time to time, Banks rose to take a more extended view of the horizon, going towards the borders of the forest which abruptly crossed the plain within a quarter of a mile of the camp. Each time on returning he looked uneasy, and only shook his head in reply to our questions.

At last we rose and accompanied him. Beneath the banyans it began to be dark already; I could see that an immense plain stretched westward up to a line of indistinct low hills which were now almost enveloped in the clouds. The aspect of the heavens was terrible in its calm. Not a breath of air stirred the leaves of the highest trees. It was not the soft repose of slumbering nature so often sung by poets, but the dull heavy sleep of sickness. There was a restrained tension in the atmosphere, like condensed steam ready to explode.

And indeed the explosion was imminent. The storm clouds were high, as is usually the case over plains, and presented wide curvilinear outlines very strongly marked. They seemed to swell out, and, uniting together, diminished in number while they increased in size. Evidently, in a short time, there would be but one dense mass spread over the sky above us. Small detached clouds at a lower elevation hurried along, attracting, repelling, and crushing one against another, then, confusedly joining the general mêlée, were lost to view.

About half-past eight a sharp flash of forked lightning rent the gloom asunder. Sixty-five seconds afterwards, a peal of thunder broke, and the hollow rumbling attendant to that species of lightning lasted about fifteen seconds.

“Sixteen miles,” said Banks, looking at his watch. “That is almost the greatest distance at which thunder can be heard. But the storm, once unchained, will travel quickly; we must not wait for it. Let us go indoors, my friends.”

“And what about Captain Hood?” said Sergeant McNeil.

“The thunder has sounded the recall,” replied Banks. “It is to be hoped he will obey orders.”

Five minutes afterwards we were seated under the verandah of our saloon.