4

Torn Between Brothers

AS JAMES STEPHENS continued to promise “war or dissolution in 1865,” General Francis Frederick Millen reported to John O’Mahony that “between June and September barely a steamer arrived” in Ireland “that did not bring fifteen of these fighting Irishmen.” According to Millen, some of the Civil War veterans were experienced officers; “others had lived loafing round the bar-rooms and engine-houses of New York—equally ready to cut a pack of cards or a throat.”

When the British government became aware of the influx of Fenians, it began to screen Irish-looking passengers arriving on steamers from the United States. If their accents didn’t betray the Fenians, their fashion often did. British authorities kept such watchful eyes for the double-breasted vests, felt hats, and square-toed shoes so popular in America that Colonel Thomas Kelly urged Fenians to leave those items at home to avoid suspicion.

On September 15, the police stormed through the front door of The Irish People, seizing books and ledgers. Across Dublin, the authorities arrested more than a dozen Irish People staffers and Irish Republican Brotherhood leaders, including Thomas Clarke Luby. In a drawer of Luby’s nightstand, police found an envelope of incriminating IRB documents that would lead to several convictions, including his own. The authorities charged the Fenians with treason felony and attempting to levy war upon the Crown, which was later increased to high treason, punishable by death. In addition to decapitating the IRB leadership, the authorities seized £5,000 of the Fenians’ money and froze the IRB’s bank account.

Stephens managed to evade capture, fleeing to a safe house in the Dublin suburbs. His advisers urged him to launch his uprising before the British could cripple the entire organization, but Stephens decided now was not the time for action. “Had we been prepared,” he wrote to O’Mahony the day after the raid, “last night would have marked an epoch in our history. But we were not prepared; and so I had to issue an order that all should go home.”

With a £2,300 reward for his capture, Stephens went into hiding. He had given clear instructions to O’Mahony in the event of his taking. “Once you hear of my arrest, only a single course remains to you,” he wrote. “Gather all the fighting men you [can] about you, and then sail for Ireland.”

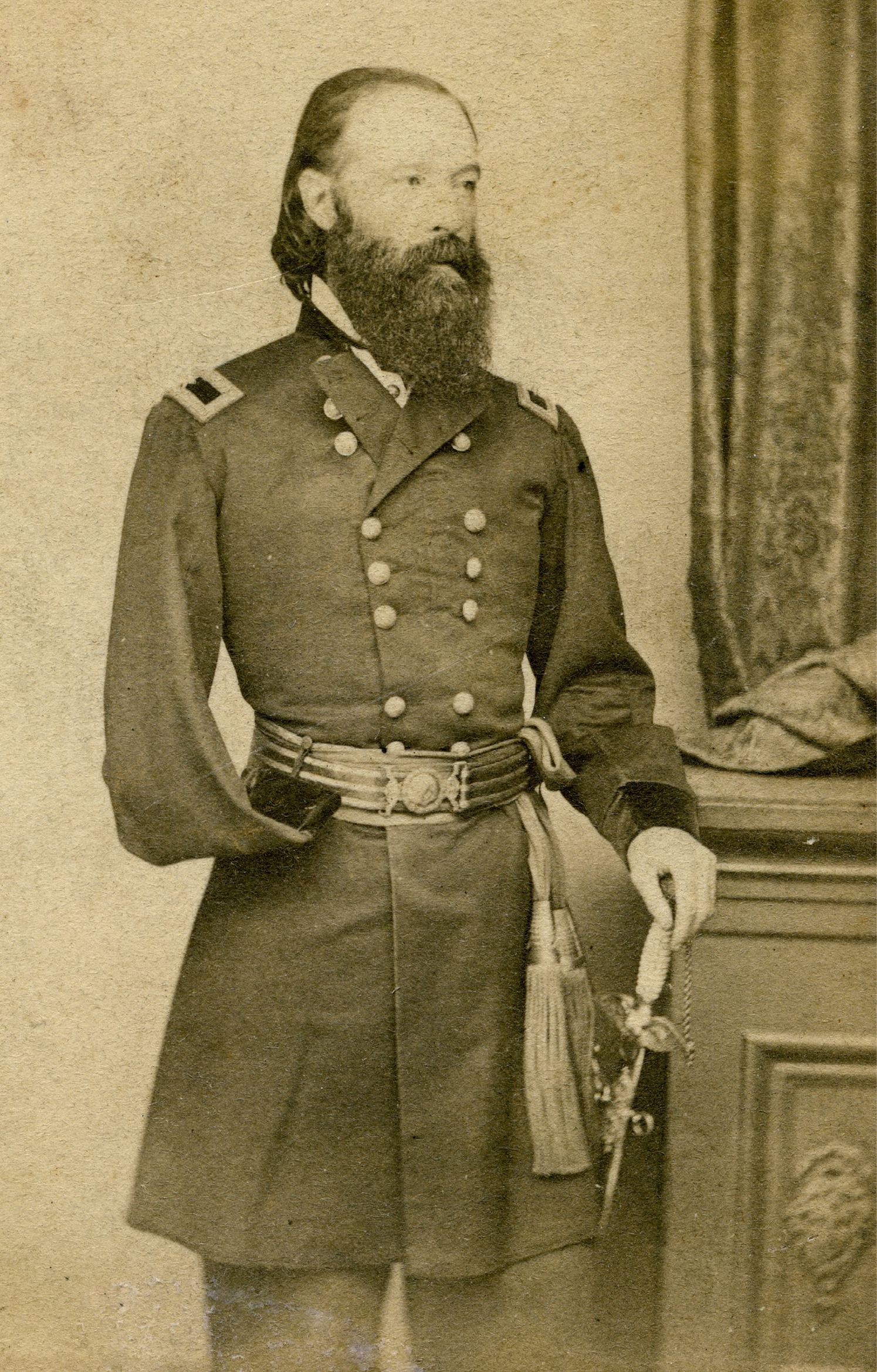

General Thomas William Sweeny picked up his pen with his left hand (his only hand), dated his letter October 12, 1865, and requested a twenty-day leave of absence from the Union army to attend to private business in New York. After the granting of his petition, the veteran of two American wars departed Nashville to attend to his affairs, which were hardly private and not in New York but in Philadelphia, where more than six hundred delegates assembled for the Fenian Brotherhood’s third general convention.

Few Americans embodied the spirit of the “fighting Irish” more than Sweeny. Leaving Ireland as an eleven-year-old, he survived thirty minutes in the Atlantic Ocean after being washed overboard during a storm on his voyage to the United States. After joining the nearly five thousand Irish-born soldiers who fought for the U.S. Army in the Mexican-American War, “Fightin’ Tom” rose to the rank of second lieutenant. During the 1847 Battle of Churubusco, Sweeny took a bullet to the groin, but still he refused to abandon his men. Minutes later, a ball pierced his right arm so completely that it had to be amputated.

Rather than wallow in self-pity, Sweeny simply folded over the empty right sleeve of his uniform jacket and continued to serve in the Second U.S. Infantry, even whipping his commanding officer in a fistfight with just his one good arm. During the Civil War, Sweeny rose to the rank of brigadier general and, according to General William Tecumseh Sherman, “saved the day” commanding a brigade at the 1862 Battle of Shiloh in spite of taking two gunshots to his remaining arm and one to the leg.

The one-armed general Thomas Sweeny left the U.S. Army to serve as the Fenian Brotherhood’s secretary of war and draw up plans for the invasion of Canada.

The career officer joined the Fenian Brotherhood while on garrison duty in Nashville. He wrote that his military service was “a school for the ultimate realization of the darling object of his heart”—Irish independence.

When he entered the convention hall in Philadelphia in the middle of October, Sweeny was the highest-profile Civil War general to align himself with the Fenian Brotherhood. Assembling just blocks away from where the Founding Fathers drafted the Declaration of Independence ninety years earlier, he and his fellow Fenians hoped for inspiration in their efforts to cast off the same tyrannical government across the ocean.

The convention’s record attendance testified to a surge of interest in the Fenian cause after the Civil War’s conclusion, particularly among those like Sweeny who were drawn to the more militant “men of action” and who sought democratic reforms to check O’Mahony’s power. In addition to approving a new constitution with a familiar-sounding preamble, “We, the Fenians of the United States,” the congress replaced the central council, whose members had been nominated by the executive, with an unpaid fifteen-person senate elected by the delegates. To curb the power of the executive, whose title changed from head center to president, the senate was given the ability to approve cabinet nominations and overrule presidential decisions with a two-thirds vote.

Delegates reelected O’Mahony as their executive. In case of his death, impeachment, or resignation, power would now fall to the president of the senate, a role filled by William Roberts, a splendid orator and one of the “men of action.” The thirty-five-year-old had arrived in New York in 1849. After working for nearly a decade for A. T. Stewart’s dry-goods emporium, Roberts launched his own successful store. His Crystal Palace Emporium on the Bowery advertised “cheap goods, at the real cost price, and no humbug.”

As he filled out his cabinet, O’Mahony appointed Sweeny his secretary of war and general commanding the “Army of the Irish Republic.” He was relieved to have an experienced hand to pull together the plan for the invasion of Ireland, which might have to be implemented soon if the British tracked down Stephens.

For his part, Sweeny asserted his belief in striking where the enemy “was most vulnerable and where victory would give us the most real positive advantage,” a notion with which O’Mahony could hardly disagree. However, unlike his fellow Fenian, Sweeny wasn’t referring to Ireland.

Sweeny believed the idea of launching a transatlantic operation to support an uprising in Ireland would be logistically impossible, particularly because the Fenians lacked a navy.

So why not strike the British where they were closer, more vulnerable, and more easily attacked? “The Canadian frontier, extending from the mouth of the St. Lawrence River to Lake Huron, a distance of more than 1,300 miles, is assailable at all points,” Sweeny wrote. The lightly defended border with Canada, which had only one-tenth of the population of the United States, was a lawless no-man’s-land frequented by counterfeiters, transnational criminals, and outlaw gangs smuggling alcohol, produce, opium, and even livestock by wagons, boats, and sleighs. The migration of fugitive slaves, draft dodgers, and Confederate agents to Canada during the Civil War proved just how porous it was.

Sweeny’s idea, backed by Roberts and the “men of action,” called for the Fenians to establish a foothold in Canada that would allow it to be granted belligerent rights by the United States, and to issue letters of marque to privateers to attack British merchant ships. They could then use Canada as a base of operations to launch a naval program that could be successful in attacking the British overseas.

The Canadian plan offered several scenarios that could result in Ireland’s independence. An attack could divert British army troops from Ireland, increasing the chances of a successful IRB uprising. It could perhaps even trigger a war between Great Britain and the United States, which had cast its land-hungry eyes northward after having expanded west and south in the prior three decades. Under another scenario, the Fenians could seize Canada and trade the colony back to the British in return for Ireland. In essence, a geopolitical kidnapping of Canada, with its ransom being Ireland’s independence.

Even the plan’s proponents understood that the chances of success weren’t in their favor. But the odds would be against the Irish no matter what they did. A slim chance is all Ireland ever faced when challenging the British over the past seven centuries. The likelihood of failure might have been high, but it was guaranteed if they did nothing at all.

Invading Canada might have sounded outrageous to some, but it followed a long American tradition of attacking the British colony. In fact, the United States had yet to even declare its independence from Great Britain when the Continental army attacked Canada in the late summer of 1775.

After marching north from Lake Champlain and seizing Montreal, the Dublin-born general Richard Montgomery continued on to the outskirts of Quebec City, where in December 1775 he united with Colonel Benedict Arnold, who had marched north through Maine. With the enlistments of many soldiers expiring the next day, the Continental army attacked during a New Year’s Eve blizzard and suffered a terrible defeat, failing to gain a stronghold on the St. Lawrence River to control the movement of goods and troops. The patriots erroneously expected to receive the support of the French Canadians in their operation, a mistake that Americans would often repeat.

After declaring war on Great Britain in 1812, the United States planned a three-pronged invasion of Canada in which it expected to be greeted as liberators, not marauders. “The acquisition of Canada…will be a mere matter of marching,” promised the former president Thomas Jefferson. It wasn’t.

The U.S. general William Hull’s attack across the Detroit River in the first weeks of the War of 1812 proved disastrous, and he surrendered his entire army without firing a single shot. General Henry Dearborn abandoned his plans to strike Montreal before the attack could even be launched, while General Stephen Van Rensselaer’s attack across the Niagara River ended in defeat at the Battle of Queenston Heights.

A quarter century later, Americans became involved in a series of failed populist uprisings that killed hundreds in Canada in the Patriot War of 1837 and 1838. In Quebec, Francophones excluded from power rebelled against English-speaking elites, while reformers in Ontario rebelled against the aristocracy over political patronage and corruption.

Rebel leaders who fled to the United States during the Patriot War found considerable support for their democratic aspirations. Secret “Hunters’ Lodges” dedicated to liberating Canada from British rule sprouted along the northern border of the United States, causing President Martin Van Buren to warn American sympathizers to obey the country’s neutrality laws. In November 1838, approximately three hundred “Hunter Patriot” insurgents, soldiers originally from both sides of the border, crossed the St. Lawrence River, only to be defeated at the Battle of the Windmill.

In the ensuing years, farcical disputes with equally ridiculous names flared along the border. In the final days of 1838, American lumberjacks spotted their Canadian counterparts chopping down trees in disputed territories of Maine and New Brunswick near the Aroostook River, setting off the bloodless Pork and Beans War (named for the lumberjacks’ meal of choice). Both Maine and New Brunswick sent militias to the border region, followed by the arrival of British forces from the Caribbean and congressional authorization for the dispatch of a fifty-thousand-man force. The arrival of Brigadier General Winfield Scott finally defused the tension, but the dispute led to a negotiated settlement of the border between the United States and Great Britain under the 1842 Webster-Ashburton Treaty.

Farther west, other portions of the boundary between Canada and the United States remained in dispute. The war cry “Fifty-four forty or fight” carried James Polk to the White House in 1844 as expansionists sought a far-northern latitude for the Oregon Territory. The subsequent Oregon Treaty settled on the 49th parallel as the international boundary, but it did not address the status of the San Juan Islands between Seattle and Vancouver, which continued to be claimed by both Great Britain and the United States.

In June 1859 on San Juan Island, the American Lyman Cutlar shot dead a pig dining on the potatoes in his garden that belonged to a ranch manager for the Canadian Hudson’s Bay Company. The situation quickly escalated. British authorities threatened Cutlar with arrest and evicted seventeen of his countrymen from the island. President James Buchanan sent troops in response. The British retaliated; their arms race continued until five hundred American troops and two thousand British aboard five warships kept watch over San Juan Island.

While the British governor of Vancouver Island urged an attack, the British rear admiral Robert L. Baynes refused to “involve two great nations in a war over a squabble about a pig.” And once again, General Scott was dispatched to calm the situation, serving as a military sedative to soothe the frayed nerves. Great Britain and the United States eventually agreed to a joint occupation of the island until the settlement of the water boundary.

At the close of the Civil War, the Fenians weren’t the only Americans thinking about an attack on Canada. After Appomattox, Senator Zach Chandler of Michigan developed a plan to dispatch 200,000 Civil War veterans—100,000 each from Grant’s and Lee’s armies—to confiscate Canada as compensation for the Alabama claims.

“If we could march into Canada an army composed of men who have worn the gray side by side with the men who have worn the blue to fight against a common hereditary enemy,” Chandler said, “it would do much to heal the wounds of the war, hasten reconstruction, and weld the North and South together by a bond of friendship.” Thirty senators signed off on the plan, but it derailed after Lincoln’s assassination.

This is all to say that in the 1860s an American invasion of Canada might not have sounded as ridiculous to American ears as it does to those today. It would receive a further shot in the arm from an unlikely and influential source.

The Civil War had decimated John Mitchel, much as it had his newly beloved South. He lost two sons in 1863, one at Fort Sumter and the other at Gettysburg. A third boy lost his arm in the war. The news, however, could not dampen his fiery rhetoric toward the American government, which arrested him in June 1865 on the vague charge of “aiding the rebellion” and consigned him to Virginia’s Fortress Monroe, where he was jailed with his friend the former Confederate president Jefferson Davis, whom he had visited frequently at the Confederate White House.

Even those who vehemently disagreed with the Irishman’s slavery stance had to wonder why General Lee remained free while Mitchel languished behind bars. Having gained O’Mahony’s approval, the St. Louis Fenian Bernard Doran Killian traveled to the nation’s capital to personally lobby President Andrew Johnson and the U.S. secretary of state William Seward for his release.

During his White House audience on October 13, Killian raised the prospect of a hypothetical Fenian invasion of Canada and seizure of Canadian territory south of the St. Lawrence River, in order to gauge the potential reaction of the American government. According to Killian’s account (the only one that exists), the pair told him that they would “acknowledge accomplished facts,” in spite of American neutrality laws. In other words, they wouldn’t endorse a Canadian invasion per se, but they wouldn’t interfere with one either.

For its part, the Johnson administration saw value in a Fenian invasion. It could be used to pressure Great Britain in the government’s quest to extract millions of dollars in reparations for the Alabama claims. Plus, with the future of Reconstruction at stake, Johnson saw a chance to earn the goodwill of the country’s 1.6 million Irish voters.

The Fenians would hang their expectation of American support on Killian’s account of the White House meeting, which he brought back to the Philadelphia convention along with news of Johnson’s agreement to release Mitchel, who subsequently spent a year in Paris as a financial agent funneling money from the Fenian Brotherhood to the IRB. Their nascent idea was gaining life.

The most wanted man in the British Empire slumbered as a posse of policemen surrounded his hideout around 6:00 a.m. on November 11. A suspicious neighbor had noticed that “Mr. Herbert,” said to be a well-to-do gentleman of private fortune and a son of a Kilkenny reverend, made only nocturnal excursions, while numerous parcels arrived for him every day. When police began to monitor the house, they saw the fugitive’s wife, Jane Stephens, entering and exiting the villa.

Scaling the high wall surrounding the property, the police closed in as Inspector Hughes rapped on the door. Eventually, they heard the voice of Stephens from the other side of the door asking if it was the gardener. When he heard that it was the police, Stephens ran to a front window and saw the house surrounded. With no escape, he opened the door and was taken into custody. Mrs. Stephens asked her husband whether she could visit him in prison, which he quickly dismissed. “You cannot visit me in prison without asking permission of British officials,” he barked, “and I do not think it becoming in one so near to me as you are to ask favors of British dogs. You must not do it—I forbid it.”

The police loaded Stephens and three Fenians sleeping in adjacent rooms into a police van and galloped away to Dublin Castle before the IRB leader’s transfer to Richmond Bridewell Prison. While past political prisoners such as William Smith O’Brien, Thomas Francis Meagher, and Daniel O’Connell resided in the governor’s residence at Richmond Bridewell Prison, Stephens received no such privilege. He remained with the general population, which was subjected to the particularly cruel Victorian punishment of the treadwheel, a contraption on which prisoners walked in place on the planks of a large paddle wheel that turned gears pumping water or crushing grain. Over the course of a monotonous eight-hour shift, a prisoner could scale the equivalent of seventy-two hundred feet, twice the height of Ireland’s tallest peak.

Two weeks after his arrest, Stephens heard a key rattling in his cell door. John Breslin, an orderly in the prison hospital and brother of an IRB member, entered and handed Stephens a six-chambered revolver. Along with the prison turnkey and IRB member Daniel Byrne, Breslin had taken beeswax impressions of the six keys needed to get Stephens outside and given them to an optician to manufacture duplicates, which he filed down until they worked.

Fleeing through the prison yard, Stephens scaled the prison wall, using a knotted rope that had been thrown over by a nine-man rescue team led by Kelly, the American envoy who had become a Stephens confidant. Stephens hauled his body up and saw the drop on the other side. Although he was nervous, the rescue team told him to jump, so Stephens fell into the arms of his fellow Fenians.

It was a daring and effective escape, but Stephens’s comportment affected at least one of its participants. He “shook like a dog in a wet sack,” reported John Devoy, a twenty-three-year-old IRB operative who had recruited the rescue team. It was in that moment he began to question the IRB leader’s nerve.

The news of Stephens’s escape shook the British Isles. Not only was the man who promised a rebellion by the end of the year free once again, but the authorities wondered if there was any place in Ireland that the Fenians had not infiltrated.

The authorities offered a £2,000 reward for the Irishman’s capture. They papered Dublin with his description, oddly citing his twitching left eye, as well as that his hands and feet were “remarkably small and well formed.” Just as in 1848, Stephens was a fugitive.

He didn’t take flight into the Irish countryside this time. Far from it. In fact, not only did he remain in Dublin, but he could see the prison from which he had just escaped from the chamber window of his temporary hideout.

Stephens’s top advisers, especially the Fenians who had traveled to Ireland from the United States, implored him that this was the moment to fight. But the IRB leader stalled. Just like when he stood on the barricade in 1848 with a rifle in his hand, just as he had the night of the Irish People raid, Stephens didn’t take the shot.

The Fenians, particularly those who had come from America, felt betrayed. “I do not know him to be a liar at all, though I do not take him to be very scrupulous about the truth,” wrote John O’Leary. “I’d believe little he said on his mere word, but that is because I believe he very easily deceives himself.”

The decision not to fight sparked not just incredulity among some Fenians but also the rumor that Stephens must be a British spy who was given his freedom in return for becoming a double agent. It was, many felt, the most plausible explanation for how he managed to break out of Ireland’s most secure prison and elude arrest.

Stephens alone had pledged that 1865 would be the year of action. Instead, Irish republicans resigned themselves to yet another year chained to the British. In Ireland and abroad, a restlessness began to grow.

Like a lodestar at night, a green Fenian banner emblazoned with a golden sunburst whipped in the November sky from atop a four-story brownstone. It guided O’Mahony to his organization’s palatial new headquarters at 32 East Seventeenth Street on the northern edge of Manhattan’s Union Square.

Tasked by the Fenian senate with leasing a new headquarters commensurate with its self-importance, Roberts, Sweeny, and Killian chose Moffat Mansion, one of New York’s plushest properties. In mid-November, the Fenians moved uptown from their cramped Duane Street quarters, huddled among saloons, tattoo parlors, and boardinghouses. Now they rubbed shoulders with the elegant Everett House hotel.

Sunlight poured through Moffat Mansion’s stained-glass windows, casting colorful rays on the frescoes, sculptures, paintings, and coats of arms adorning the walls. Behind the great glass folding door of the reception room sat cabinet secretaries and senators eager for an audience with the president. In adjoining rooms, treasury department clerks counted incoming donations and paid bills.

The Fenians thought their opulent accommodations were symbolic of their emergence on the world stage. Respectability came at a price, however. They leased the “Fenian White House” for eighteen months at a cost of $18,000 paid in advance. They also emptied the treasury of $5,000 to be placed as a security against damages. On top of the rent, the Fenians spent several thousand dollars to purchase rosewood desks, luxurious carpets, and armchairs upholstered in green and gold.

For a man comfortable wearing threadbare clothing and living in rude apartments like the one he shared with Stephens in Paris, O’Mahony could only shake his head at the lavish expense and mutter to a friend that he feared “it might prove the tomb of the Fenian movement.” On the second floor, O’Mahony navigated his way through the traffic of scurrying clerks filing correspondence and transmitting presidential orders and entered his private office. While Sweeny and the ordnance bureau, corps of engineers, and rest of the war department on the third floor pored over maps, organized a secret service corps in Canada, and crafted the plan for attacking America’s northern neighbor, O’Mahony followed the directive that Stephens issued two months earlier to gather all the fighting men he could and sail for Ireland as soon as he learned of his capture.

In November 1865, the Fenian Brotherhood moved its headquarters into the plush Moffat Mansion on the north side of Manhattan’s Union Square.

Like any self-respecting government, the provisional government of the Irish Republic in exile now had its own declaration of independence, its own constitution, its own president and senate, its own army, and now its own grand capitol. The Fenians even issued their own bond notes in denominations of $10, $20, $50, $100, and $500. Printed in green and black, the bonds featured patriotic symbols including a harp, an Irish round tower, and portraits of Irish nationalist heroes such as Robert Emmet and Theobald Wolfe Tone. In the center of the bond, a woman representing Erin, with an Irish wolfhound at her feet, pointed with her left hand to a distant sunburst rising over Ireland and with her right to an unsheathed sword on the ground, about to be grasped by an Irish soldier. The bonds could be redeemed six months after the establishment of the Irish Republic with interest at 6 percent a year.*

Despite its grand appearances, all was not well at Moffat Mansion, which was rife with tension from the day the Fenians first arrived. O’Mahony continued to feud with the senate over its war strategy. Stephens learned of the estrangement, and he threw his backing behind his fellow Young Irelander, no matter what grievances he might have had with him. Stephens condemned Sweeny’s proposed Canadian foray as a “traitorous diversion from the right path.”

The division erupted into an irreparable schism over the issue of the Fenian bonds. After O’Mahony ordered Killian, the Fenian treasurer, to deny Sweeny’s request for money to purchase guns for a Canadian attack, the Fenian bond agent, Patrick Keenan, resigned his position at the senate’s behest, meaning that no further bonds could be issued.

Believing the situation in Ireland to be an emergency, O’Mahony proceeded to issue bonds with his signature on them, although he lacked the constitutional authority to do so. The senate drew up articles of impeachment against O’Mahony in response, charging him with violating the Fenian constitution, engaging in financial irregularities, and lining his own pockets by drawing the $1,200 annual salary of the bond agent in addition to the president’s $2,000 yearly payment. The senators accused O’Mahony of extravagant spending, pointing to Moffat Mansion as the prime example (although the decision to rent the property was clearly more theirs than his).

The Fenian Brotherhood had managed to survive the Civil War intact, only to now tear itself apart. Meeting in special session, the senate removed O’Mahony from the presidency for eleven specific violations of his oath of office and replaced him with Roberts, the senate president. Having shepherded the Fenian Brotherhood since its inception, O’Mahony was hardly about to step aside without a fight. He retaliated by expelling Roberts and Keenan from the Fenian Brotherhood, seizing control of the treasury and the keys to Moffat Mansion. The so-called Roberts wing formed its own competing Irish Republic government in exile, with headquarters on Broadway, just around the corner from Moffat Mansion.

The Irish Republic might not have had land of its own, but it now had two headquarters, two presidents, and two divergent plans for freeing Ireland.

Across North America, the Fenian movement cleaved into competing circles: those loyal to Roberts or O’Mahony. While East Coast Fenians tended to remain with O’Mahony, the Roberts wing found its base of support in the Midwest. For some, the decision was not easy. F. B. McNamee reported that his circle in Montreal was “ready to ‘go in,’ for which ever party is in the field first.”

Although the Fenian movement was pulling itself apart, the British remained concerned with the American government’s coddling of the Irishmen, in particular the War Department’s decision to grant Sweeny a leave of absence from the military to plot an attack against them. “It seems to me that he ought to be called to choose between the North American and the Irish Republic,” Sir Frederick Bruce, the British minister to Washington, D.C., complained to Seward. “The effect of his acting as Secretary of War is to confirm the Fenian dupes in the belief that the Government of the United States favors the movement.”

The British protest might have been what led to the denial of Sweeny’s request for a six-month leave of absence and his dismissal from the Union army on Christmas Day. Sweeny had given twenty years of his life—and one limb—in service of the United States, but the call of his homeland was powerful enough that he was willing to walk away.

One day after celebrating the arrival of the new year of 1866, six hundred delegates of the O’Mahony wing congregated in New York’s Clinton Hall. The convention rescinded the Fenian constitution, which had been agreed to in Philadelphia just four months earlier, and reverted to the prior one drafted at the 1863 convention in Chicago. This meant that O’Mahony would be reinstated as head center, advised by a five-man council elected by the congress. The convention also approved a resolution endorsing war in Ireland—and only Ireland.

Sweeny and Roberts—both Protestants—captured headlines as they visited Irish enclaves from New York to Illinois to Tennessee, loudly pronouncing their intention to attack Canada by July. The duo relished these public events. Sweeny’s charisma combined with Roberts’s oratorical skills generated excitement and sold out theaters.

By the time the Roberts wing held its own convention behind the closed doors of Pittsburgh’s Masonic Hall in February, it had stolen the headlines from the O’Mahony wing. Many Irish Americans agreed with Sweeny that the Roberts wing had “the only feasible plan to the liberation of Ireland.” Sweeny there unveiled his war plan to attack Canada. The measure was overwhelmingly adopted. “We promise that before the summer sun kisses the hilltops of Ireland,” Sweeny thundered, “a ray of hope will gladden every true Irish heart, for by that time we shall have conquered and got hostages for our brave patriots at home.”

A native of Ireland, the dry-goods magnate William Roberts favored an invasion of Canada and led the senate wing after its break with John O’Mahony, who advocated a Fenian uprising in Ireland.

Following the convention, the Roberts wing grew its membership through a network of salaried recruiters and organizers who evangelized for the Fenian cause in hopes of getting the Irish to open their wallets and establish new circles. These “missionaries” visited mining towns and mill cities for weeks at a time, traveling by train to a different locale each night. They tugged on the emotional strings of the Irish in events that mirrored revival meetings, with brass bands and Irish jigs as entertainment.

The Fenian Brotherhood held a particular appeal to Irish immigrants in rural areas of the Midwest and the West that lacked the political machines, parishes, and immigrant aid societies that bound the Irish together in the big cities of the East. Like other Irish fraternal organizations, the Fenian Brotherhood offered a sense of community. While some joined out of a desire to free their homeland, others did so primarily to maintain their ethnic identity and meet fellow Irishmen.

Fenian organizers, though, continued to battle clerical opposition. In Sharon, Pennsylvania, fifteen young men had been ready to start a circle until, as one Irishman reported, “Father O’Keefe spoke of the Fenians last Sunday and call[ed] us children of hell and said that he was ordered by the Bishop of Erie to stop our progress.”

Thanks to the work of the organizers, the momentum in the Irish republican movement resided with the Roberts wing in early 1866. Events in Ireland, however, would give both American factions a jolt of energy.

Nearly three months after his prison escape, Stephens remained on the loose, hundreds of Civil War veterans from America loitered about Ireland, and the British government remained fearful of a possible uprising. On February 17, 1866, the British government suspended habeas corpus in Ireland, allowing suspicious persons to be detained without reason. The British prime minister, Lord John Russell, told Parliament the move was necessary to address the threat of violence being imported from the United States.

The following morning, a squad of nearly fifty detectives met at dawn and fanned out around Dublin rounding up Irish Americans, many of whom had no apparent employment yet never seemed to lack for money as they stayed at respectable hotels. Colonel John W. Byron was even arrested at a Lower Gloucester Street brothel. In Dublin alone, authorities locked up 150 Irishmen, one-third of them natural-born or naturalized American citizens suspected of Fenian activity. Similar scenes occurred in Tipperary, Limerick, Cork, Belfast, and Sligo.

The crackdown further inflamed anti-British passions among Americans, causing Seward to lodge a protest about the treatment of his fellow citizens. O’Mahony called on all Irishmen in the New York area to attend a massive protest at the Jones’s Wood estate, a popular Manhattan picnic ground along the East River, on the Sunday afternoon of March 4. That morning, New York’s archbishop, John McCloskey, had denounced the Fenians from the pulpit of old St. Patrick’s Cathedral and called on all God-fearing Catholics to stay away from the afternoon’s event, which he called “a profanation of the Lord’s Day.” He warned that attendance would provoke “the anger of God.”

If he was right, the Almighty would have been quite upset that afternoon. Even on a wintry day, 100,000 Fenians—most of them members of the Catholic flock—gathered in the pastures of Jones’s Wood. “When the priests descend into the arena of worldly politics they throw off their sacred robes,” O’Mahony had asserted. The turnout showed that the Fenians had succeeded in training many Catholics to disregard the clergy in political matters.

As snowflakes began to fall and the wind grew more biting, Fenians reached into their pockets, purchasing bond after bond to fund the establishment of the Irish Republic. Mass meetings were held in many other American cities, and for days afterward money poured into Moffat Mansion.

Nothing happened along Canada’s frontier with the United States without Gilbert McMicken knowing about it. During the Civil War, he had organized Canada’s first secret service to monitor Confederate activities along the frontier. Now the spymaster had been directed by John A. Macdonald, the province’s joint premier, to keep a close surveillance of all Fenian activities.

Having dispatched agents to infiltrate Fenian circles—and even going undercover himself to a Fenian congress—McMicken had received reports of suspicious-looking Irishmen crossing the border in advance of an imminent invasion. One of his agents monitoring the Fenians said that they planned to attack on March 17—St. Patrick’s Day.

Rumors flew that the Fenians planned to dispatch three ironclads to Halifax, poison the reservoirs of Montreal, and infect Canadian hogs with trichinosis. President Johnson had been less than transparent when he assured Bruce in January 1866 that the Fenians “met with no sympathy on the part of the Government, which on the contrary was anxious to discourage it.” Canadians were skeptical of such claims. In response to the reports, authorities called out ten thousand volunteers, and civic authorities in Toronto, Ottawa, and Montreal canceled their official St. Patrick’s Day parades.

At the White House, the cabinet debated how to handle the situation. Secretary of War Edwin Stanton advocated for Johnson to issue a presidential proclamation warning citizens against violations of the neutrality laws, much as President Martin Van Buren had done during the Patriot War of 1837. Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles argued that Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant should instead be consulted and sent to the Canadian frontier.

Welles had his way and the task fell to Grant, who ordered Major General George Meade, the hero of Gettysburg who now served as commander of the Military Division of the Atlantic, to “use all vigilance to prevent armed or hostile forces or organizations from leaving the United States” and attacking Canada. Not that Grant was enthusiastic about the mission. “During our late troubles neither the British Government or the Canadian officials gave themselves much trouble to prevent hostilities being organized against the United States from their possessions,” Grant wrote to Meade. “But two wrongs never make a right and it is our duty to prevent wrong on the part of our people.”

Meade directed Major General Joseph Hooker to seize arms, munitions, and contraband of war that could be found along the frontier, though he didn’t see how he could stop an Irish invasion without very considerable reinforcements, because there were fewer than four hundred soldiers along the border in New York and none in New England.

When St. Patrick’s Day arrived, America’s northern border remained quiet. The only Irishmen marching through the streets of Montreal did so to greet the governor-general, the queen’s representative in Canada, with cheers. Canadians breathed a sigh of relief as the Fenian threat appeared to pass. “I do not think Sweeny will trouble you for some time to come. Your preparations have evidently dampened the Fenian ardor,” wrote Edward Archibald, the British consul in New York, to a Canadian official.

Canada might have remained quiet on March 17, but the Irish celebrated loudly on the streets of New York. The first St. Patrick’s Day since the end of the Civil War slaughter always promised to be enthusiastic, but the British suspension of habeas corpus in the homeland had put an extra determination in the steps of the thirty thousand Celtic marchers. It appeared that every Irishman in New York was joining in the celebration—except for one notable Fenian.