approaching research planning

approaching research planningPlanning educational research |

CHAPTER 7 |

This chapter sets out a range of key issues in planning research, including:

approaching research planning

approaching research planning

a framework for planning research

a framework for planning research

conducting and reporting a literature review

conducting and reporting a literature review

searching for literature on the internet

searching for literature on the internet

orienting decisions in planning research

orienting decisions in planning research

research design and methodology

research design and methodology

how to operationalize research questions

how to operationalize research questions

data analysis

data analysis

presenting and reporting the results

presenting and reporting the results

a planning matrix for research

a planning matrix for research

managing the planning of research

managing the planning of research

ensuring quality in the planning of research

ensuring quality in the planning of research

It also provides an extended worked example of planning a piece of research.

There is no single blueprint for planning research. Research design is governed by the notion of ‘fitness for purpose’. The purposes of the research determine the methodology and design of the research. For example, if the purpose of the research is to map the field, or to make generalizable comments then a survey approach might be desirable, using some form of stratified sample; if the effects of a specific intervention are to be evaluated then an experimental or action research model may be appropriate; if an in-depth study of a particular situation or group is important then an ethnographic model might be suitable.

That said, it is possible, nevertheless, to identify a set of issues that researchers need to address, regardless of the specifics of their research. This chapter addresses this set of issues, to indicate those matters that need to be addressed in practice so that an area of research interest can become practicable and feasible. This chapter indicates how research might be operationalized, i.e. how a general set of research aims and purposes can be translated into a practical, researchable topic.

It is essential to try as far as possible to plan every stage of the research. To change the ‘rules of the game’ in midstream once the research has commenced is a sure recipe for problems. The terms of the research and the mechanism of its operation must be ironed out in advance if it is to be credible, legitimate and practicable. Once they have been decided upon, the researcher is in a very positive position to undertake the research. The setting up of the research is a balancing act, for it requires the harmonizing of planned possibilities with workable, coherent practice, i.e. the resolution of the difference between what could be done/what one would like to do and what will actually work/what one can actually do, for, at the end of the day, research has to work. In planning research there are two phases: a divergent phase and a convergent phase. The divergent phase will open up a range of possible options facing the researcher, whilst the convergent phase will sift through these possibilities, see which ones are desirable, which ones are compatible with each other, which ones will actually work in the situation, and move towards an action plan that can realistically operate. This can be approached through the establishment of a framework of planning issues.

What the researcher does depends on what the researcher wants to know and how she or he will go about finding out about the phenomenon in question. The planning of research (the research design) depends on the kind(s) of questions being asked or investigated. This is not a mechanistic exercise, but depends on the researcher’s careful consideration of the purpose of the research (discussed in the previous chapter) and the phenomenon being investigated, for example see Table 7.1.

Part 1 set out a range of paradigms which inform and underpin the planning and conduct of research, for example:

positivist and post-positivist

positivist and post-positivist

quantitative, scientific and hypothesis-testing

quantitative, scientific and hypothesis-testing

qualitative

qualitative

interpretive and naturalistic

interpretive and naturalistic

phenomenological and existential

phenomenological and existential

interactionist and ethnographic

interactionist and ethnographic

experimental

experimental

ideology critical

ideology critical

participatory

participatory

feminist

feminist

political

political

complexity theoretical

complexity theoretical

evaluative

evaluative

mixed methods.

mixed methods.

TABLE 7.1 PURPOSES AND KINDS OF RESEARCH

Kinds of research purpose |

Kinds of research |

Does the research want to test a hypothesis or theory? |

Experiment, survey, action research, case study |

Does the research want to develop a theory? |

Ethnography, qualitative research, grounded theory |

Does the research need to measure? |

Survey, experiment |

Does the research want to understand a situation? |

Ethnographic and interpretive/qualitative approaches |

Does the research want to see what happens if . . .? |

Experiment, participatory research, action research |

Does the research want to find out ‘what’ and ‘why’? |

Mixed methods research |

Does the research want to find out what happened in the past? |

Historical research |

It was argued that these paradigms rest on different ontologies (e.g. different views of the essential nature or characteristics of the phenomenon in question) and different epistemologies (e.g. theories of the nature of knowledge, its structure, organization and how we investigate knowledge and phenomena: how we know, what constitutes valid knowledge, our cognition of a phenomenon). For example:

a positivist paradigm rests, in part, on an objectivist ontology and a scientific, empirical, hypothesistesting epistemology;

a positivist paradigm rests, in part, on an objectivist ontology and a scientific, empirical, hypothesistesting epistemology;

an interpretive paradigm rests, in part, on a subjectivist, interactionist, socially constructed ontology and on an epistemology that recognized multiple realities, agentic behaviours and the importance of understanding a situation through the eyes of the participants;

an interpretive paradigm rests, in part, on a subjectivist, interactionist, socially constructed ontology and on an epistemology that recognized multiple realities, agentic behaviours and the importance of understanding a situation through the eyes of the participants;

a complexity theory paradigm rests, in part, on an ontology of self-organized emergence and change through the unpredictable interactions and outcomes of constituent elements of a whole ecological entity, and on an epistemology that argues for understanding multiple directions of causality and a need to understand phenomena holistically and by examining the processes and outcomes of interactions;

a complexity theory paradigm rests, in part, on an ontology of self-organized emergence and change through the unpredictable interactions and outcomes of constituent elements of a whole ecological entity, and on an epistemology that argues for understanding multiple directions of causality and a need to understand phenomena holistically and by examining the processes and outcomes of interactions;

an ideology critique paradigm rests, in part, on an ontology of phenomena as organized both within, and as outcomes of, power relations and asymmetries of power, inequality and empowerment, and on an epistemology that is explicitly political, critiquing the ideological underpinnings of phenomena that perpetuate inequality and asymmetries of power to the advantage of some and the disadvantage of others, and the need to combine critique with participatory action for change to being about greater social justice;

an ideology critique paradigm rests, in part, on an ontology of phenomena as organized both within, and as outcomes of, power relations and asymmetries of power, inequality and empowerment, and on an epistemology that is explicitly political, critiquing the ideological underpinnings of phenomena that perpetuate inequality and asymmetries of power to the advantage of some and the disadvantage of others, and the need to combine critique with participatory action for change to being about greater social justice;

a mixed methods paradigm rests on an ontology that recognizes that phenomena are complex to the extent that single methods approaches might result in partial, selective and incomplete understanding, and on an epistemology that requires pragmatic combinations of methods – in sequence, in parallel or in synthesis – in order to fully embrace and comprehend the phenomenon and to do justice to its several facets.

a mixed methods paradigm rests on an ontology that recognizes that phenomena are complex to the extent that single methods approaches might result in partial, selective and incomplete understanding, and on an epistemology that requires pragmatic combinations of methods – in sequence, in parallel or in synthesis – in order to fully embrace and comprehend the phenomenon and to do justice to its several facets.

At issue here is the need for researchers not only to consider the nature of the phenomenon under study, but what are or are not the ontological premises that underpin it, the epistemological bases for investigating it and conducting the research into it. These are points of reflection and decision, turning the planning of research from being solely a mechanistic or practical exercise into a reflection on the nature of knowledge and the nature of being.

Planning research depends on the design of the research which, in turn, depends on (a) the kind of questions being asked or investigated; (b) the purposes of the research; (c) the research paradigms and principles in which one is working, and the philosophies, ontologies and epistemologies which underpin them. Planning research is not an arbitrary matter. There will be different designs for different types of research, and we give three examples here.

For example, a piece of quantitative research that seeks to test a hypothesis could proceed thus:

Literature review → generate and formulate the hypothesis/the theory to be tested/the research questions to be addressed → design the research to test the hypothesis/theory (e.g. an experiment a survey) → conduct the research → analyse results → consider alternative explanations for the findings → report whether the hypothesis/theory is supported or not supported, and/or answer the research questions → consider the generalizability of the findings.

A qualitative or ethnographic piece of research could have a different sequence, for example:

Identify the topic/group/phenomenon in which you are interested → literature review → design the research questions and the research and data collection → locate the fields of study and your role in the research and the situation → locate informants, gatekeepers, sources of information → develop working relations with the participants → conduct the research and the data collection simultaneously → conduct the data analysis either simultaneously, on an ongoing basis as the situation emerges and evolves, or conduct the data analysis subsequent to the research → report the results and the grounded theory or answers to the research questions that emerge from the research → generate a hypothesis for further research or testing.

One can see in the examples that, for one method the hypothesis drives the research whilst for another the hypothesis (if, in fact, there is one) emerges from the research, at the end of the study (some qualitative research does not proceed to this hypothesis-raising stage).

A mixed methods research might proceed thus:

Identify the problem or issue that you wish to investigate → identify your research questions → identify the several kinds of data and the methods for collecting them which, together and/or separately will yield answers to the research questions → plan the mixed methods design (e.g. parallel mixed design, fully integrated mixed design, sequential mixed design (see Chapter 1)) → conduct the research → analyse results → consider alternative explanations for the findings → answer the research questions → report the results.

These three examples proceed in a linear sequence; this is beguilingly deceptive, for rarely is such linearity so clear. The reality is that:

different areas of the research design influence each other;

different areas of the research design influence each other;

research designs, particularly in qualitative, naturalistic and ethnographic research, change, evolve and emerge over time rather than being a ‘once-and-for-all’ plan that is decided and finalized at the outset of the research;

research designs, particularly in qualitative, naturalistic and ethnographic research, change, evolve and emerge over time rather than being a ‘once-and-for-all’ plan that is decided and finalized at the outset of the research;

ethnographic and qualitative research starts with a very loose set of purposes and research questions, indeed there may not be any;

ethnographic and qualitative research starts with a very loose set of purposes and research questions, indeed there may not be any;

research does not always go to plan, so designs change.

research does not always go to plan, so designs change.

In recognition of this Maxwell (2005: 5–6) develops an interactive (rather than linear) model of research design (for qualitative research), in which key areas are mutually informing and shape each other. His five main areas are:

1 Goals (informed by perceived problems, personal goals, participant concerns, funding and funder goals, and ethical standards);

2 Conceptual framework (informed by personal experience, existing theory and prior research, exploratory and pilot research, thought experiments, and preliminary data and conclusions);

3 Research questions (informed by participant concerns, funding and funder goals, ethical standards, the research paradigm);

4 Methods (informed by the research paradigm, researcher skills and preferred style of research, the research setting, ethical standards, funding and funder goals, and participant concerns); and

5 Validity (informed by the research paradigm, preliminary data and conclusions, thought experiments, exploratory and pilot research, and existing theory and a priori research).

At the heart of Maxwell’s model lie the research questions (3), but these are heavily informed by the four other areas. Further, Maxwell attributes strong connections between goals (1) and conceptual frameworks (2), and between methods (4) and validity (5). The links between conceptual frameworks (2) and validity (5) are less strong, as are the links between goals (1) and methods (4). His model is iterative and recursive over time; the research design emerges from the interplay of these elements and as the research unfolds.

Though, clearly, the set of issues that constitute a framework for planning research will need to be interpreted differently for different styles of research, nevertheless it is useful to indicate what those issues might be, and some of these are included in Box 7.1.

BOX 7.1 THE ELEMENTS OF RESEARCH DESIGN

1 A clear statement of the problem/need that has given rise to the research.

2 A clear grounding in literature for construct and content validity: theoretically, substantively, conceptually, methodologically.

3 Constraints on the research (e.g. access, time, people, politics).

4 The general aims and purposes of the research.

5 The intended outcomes of the research: what the research will do and what are the ‘deliverable’ outcomes.

6 Reflecting on the nature of the phenomena to be investigated, and how to address their ontological and epistemological natures.

7 How to operationalize research aims and purposes.

8 Generating research questions (where appropriate) (specific, concrete questions to which concrete answers can be given) and hypotheses (if appropriate).

9 The foci of the research.

10 Identifying and setting in order the priorities for the research.

11 Approaching the research design.

12 Focusing the research.

13 Research methodology (approaches and research styles, e.g. survey; experimental; ethnographic/naturalistic; longitudinal; cross-sectional; historical; correlational; ex post facto).

14 Ethical issues and ownership of the research (e.g. informed consent; overt and covert research; anonymity; confidentiality; non-traceability; non-maleficence; beneficence; right to refuse/withdraw; respondent validation; research subjects; social responsibility; honesty and deception).

15 Politics of the research: who is the researcher; researching one’s own institution; power and interests; advantage; insider and outsider research.

16 Audiences of the research.

17 Instrumentation, e.g. questionnaires; interviews; observation; tests; field notes; accounts; documents; personal constructs; role play.

18 Sampling: size/access/representativeness; type; probability: random, systematic, stratified, cluster, stage, multi-phase; non-probability: convenience, quota, purposive, dimensional, snowball.

19 Piloting: technical matters: clarity, layout and appearance, timing, length, threat, ease/difficulty, intrusiveness; questions: validity, elimination of ambiguities, types of questions (e.g. multiple choice, open-ended, closed), response categories, identifying redundancies; pre-piloting: generating categories, grouping and classification.

20 Time frames and sequence (what will happen, when and with whom).

21 Resources required.

22 Reliability and validity: validity: construct; content; concurrent; face; ecological; internal; external; reliability: consistency (replicability); equivalence (inter-rater, equivalent forms), predictability; precision; accuracy; honesty; authenticity; richness; dependability; depth; overcoming Hawthorne and halo effects; triangulation: time; space; theoretical; investigator; instruments.

23 Data analysis.

24 Verifying and validating the data.

25 Reporting and writing up the research.

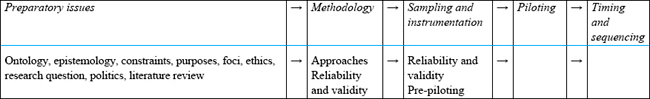

A possible sequence of consideration is:

Clearly this need not be the actual sequence; for example it may be necessary to consider access to a possible sample at the very outset of the research.

These issues can be arranged into four main areas (Morrison, 1993):

1 orienting decisions;

2 research design and methodology;

3 data analysis;

4 presenting and reporting the results.

These are discussed later in this chapter. Orienting decisions are those decisions which set the boundaries or the constraints on the research. For example, let us say that the overriding feature of the research is that it has to be completed within six months; this will exert an influence on the enterprise. On the one hand it will ‘focus the mind’, requiring priorities to be settled and data to be provided in a relatively short time. On the other hand this may reduce the variety of possibilities available to the researcher. Hence questions of timescale will affect:

the research questions which might be answered feasibly and fairly (for example, some research questions might require a long data collection period);

the research questions which might be answered feasibly and fairly (for example, some research questions might require a long data collection period);

the number of data collection instruments used (for example, there might be only enough time for a few instruments to be used);

the number of data collection instruments used (for example, there might be only enough time for a few instruments to be used);

the sources (people) to whom the researcher might go (for example, there might only be enough time to interview a handful of people);

the sources (people) to whom the researcher might go (for example, there might only be enough time to interview a handful of people);

the number of foci which can be covered in the time (for example, for some foci it will take a long time to gather relevant data);

the number of foci which can be covered in the time (for example, for some foci it will take a long time to gather relevant data);

the size and nature of the reporting (there might only be time to produce one interim report).

the size and nature of the reporting (there might only be time to produce one interim report).

By clarifying the timescale a valuable note of realism is injected into the research, which enables questions of practicability to be answered.

Let us take another example. Suppose the overriding feature of the research is that the costs in terms of time, people and materials for carrying it out are to be negligible. This, too, will exert an effect on the research. On the one hand it will inject a sense of realism into proposals, identifying what is and what is not manageable. On the other hand it will reduce, again, the variety of possibilities which are available to the researcher. Questions of cost will affect:

the research questions which might be feasibly and fairly answered (for example, some research questions might require: (a) interviewing which is costly in time both to administer and transcribe; (b) expensive commercially produced data collection instruments, e.g. tests, and costly computer services, which may include purchasing software for example);

the research questions which might be feasibly and fairly answered (for example, some research questions might require: (a) interviewing which is costly in time both to administer and transcribe; (b) expensive commercially produced data collection instruments, e.g. tests, and costly computer services, which may include purchasing software for example);

the number of data collection instruments used (for example, some data collection instruments, e.g. postal questionnaires, are costly for reprographics and postage);

the number of data collection instruments used (for example, some data collection instruments, e.g. postal questionnaires, are costly for reprographics and postage);

the people, to whom the researcher might go (for example, if teachers are to be released from teaching in order to be interviewed then cover for their teaching may need to be found);

the people, to whom the researcher might go (for example, if teachers are to be released from teaching in order to be interviewed then cover for their teaching may need to be found);

the number of foci which can be covered in the time (for example, in uncovering relevant data, some foci might be costly in researcher’s time);

the number of foci which can be covered in the time (for example, in uncovering relevant data, some foci might be costly in researcher’s time);

the size and nature of the reporting (for example, the number of written reports produced, the costs of convening meetings).

the size and nature of the reporting (for example, the number of written reports produced, the costs of convening meetings).

Certain timescales permit certain types of research, e.g. a short timescale permits answers to short-term issues, whilst long-term or large questions might require a long-term data collection period to cover a range of foci. Costs in terms of time, resources and people might affect the choice of data collection instruments. Time and cost will require the researcher to determine, for example, what will be the minimum representative sample of teachers or students in a school, as interviews are time-consuming and questionnaires are expensive to produce. These are only two examples of the real constraints on the research which must be addressed. Planning the research early on will enable the researcher to identify the boundaries within which the research must operate and what the constraints are on it.

Further, some research may be ‘front-loaded’ whilst other kinds are ‘end-loaded’. ‘Front-loaded’ research is that which takes a considerable time to set up, for example to develop, pilot and test instruments for data collection, but then the data are quick to process and analyse. Quantitative research is often of this type (e.g. survey approaches) as it involves identifying the items for inclusion on the questionnaire, writing and piloting the questionnaire, and making the final adjustments. By contrast, ‘end-loaded’ research is that which may not take too long to set up and begin, but then the data collection and analysis may take a much longer time. Qualitative research is often of this type (e.g. ethnographic research), as a researcher may not have specific research questions in mind but may wish to enter a situation, group or community and only then discover – as they emerge over time – the key dynamics, features, characteristics and issues in the group (e.g. Turnbull’s (1972) notorious study of the descent into inhumanity of the contemptible Ik tribe in their quest for daily survival as ‘The Mountain People’). Alternatively a qualitative researcher may have a research question in mind but an answer to this may require a prolonged ethnography of a group (e.g. Willis’s (1977) celebrated study of ‘how working-class kids get working-class jobs, and others let them’). Between these two types – ‘front-loaded’ and ‘end-loaded’ – are many varieties of research that may take different periods of time to set up, conduct, analyse data and report the results. For example, a mixed methods research project may have several stages (Table 7.2).

In Table 7.2, in Example One, in the first two stages of the research, the mixed methods run in sequence (qualitative then quantitative), and are only integrated in the final stage. In Example Two, in the first two stages the quantitative and qualitative stages run in parallel, i.e. they are separate from each other, and they only combine in the final stage of the research. In Example Three the mixed methods are synthesized – combined – from the very start of the research.

The researcher must look at the timescales that are both required and available for planning and conducting the different stages of the research project.

Let us take another important set of questions: is the research feasible? Can it actually be done? Will the researchers have the necessary access to the schools, institutions and people? These issues were explored in the previous chapter. This issue becomes a major feature if the research is in any way sensitive (see Chapter 9).

TABLE 7.2 THREE EXAMPLES OF PLANNING FOR TIME FRAMES FOR DATA COLLECTION IN MIXED METHODS RESEARCH

Example One |

Example Two |

Example Three |

Qualitative data to answer research questions in total or in part, or to develop items for quantitative instruments (e.g. a numerical questionnaire survey) |

Quantitative data and qualitative data in parallel to answer research questions in total or in part, or to identify participants for qualitative study |

Quantitative and qualitative data together to answer research questions in total or in part and to raise further research questions |

|

|

|

Quantitative data to answer research questions in total or in part, or to identify participants for qualitative study (e.g. interviews) |

Quantitative and qualitative data in parallel to answer research questions in total or in part |

Quantitative and qualitative data to answer research questions in total or in part |

|

|

|

Quantitative and qualitative data to answer one or more research questions |

Quantitative and qualitative data to answer one or more research questions |

Quantitative and qualitative data to answer research questions in total or in part |

Before one can progress very far in planning research it is important to ground the project in validity and reliability. This is achieved, in part, by a thorough literature review of the state of the field and how it has been researched to date. Chapter 6 indicated that it is important for a researcher to conduct and report a literature review. A literature review should establish a theoretical framework for the research, indicating the nature and state of the theoretical and empirical fields and important research that has been conducted and policies that have been issued, defining key terms, constructs and concepts, reporting key methodologies used in other research into the topic. The literature review sets out what the key issues are in the field to be explored, and why they are, in fact, key issues, and it identifies gaps that need to be plugged in the field. As Chapter 6 indicated, all of this contributes not only to the credibility and validity of the research but to its topicality and significance, and it acts as a springboard into the study, defining the field, what needs to be addressed in it, why, and how it relates to – and extends – existing research in the field.

A literature review may report contentious areas in the field and why they are contentious; contemporary problems that researchers are trying to investigate in the field; difficulties that the field is facing from a research angle; new areas that need to be explored in the field.

A literature review synthesizes several different kinds of materials into an ongoing, cumulative argument that leads to a conclusion (e.g. of what needs to be researched in the present research, how and why). It can be like an extended essay that sets out clearly:

the argument(s) that the literature review will advance;

the argument(s) that the literature review will advance;

points in favour of the argument(s) or thesis to be advanced/supported;

points in favour of the argument(s) or thesis to be advanced/supported;

points against the argument(s) or thesis to be advanced/supported;

points against the argument(s) or thesis to be advanced/supported;

a conclusion based on the points raised and evidence presented in the literature review.

a conclusion based on the points raised and evidence presented in the literature review.

There are several points to consider in researching and writing a literature review (cf. University of North Carolina, 2007; Heath, 2009; University of Loughborough, 2009). A literature review:

establishes and justifies the need for the research to be conducted, and establishes its significance and originality;

establishes and justifies the need for the research to be conducted, and establishes its significance and originality;

establishes and justifies the methodology to be adopted in the research;

establishes and justifies the methodology to be adopted in the research;

establishes and justifies the focus of the research;

establishes and justifies the focus of the research;

is not just a descriptive summary, but an organized and developed argument, usually with subtitles, such that, if the materials were presented in a sequence other than that used, the literature review would lose meaning, coherence, cogency, logic and purpose;

is not just a descriptive summary, but an organized and developed argument, usually with subtitles, such that, if the materials were presented in a sequence other than that used, the literature review would lose meaning, coherence, cogency, logic and purpose;

presents, contextualizes, analyses, interprets, critiques and evaluates sources and issues, not just accepting what they say (e.g. it exposes and addresses what the sources overlook, misinterpret, misrepresent, neglect, say something that is contentious, about which they are outdated);

presents, contextualizes, analyses, interprets, critiques and evaluates sources and issues, not just accepting what they say (e.g. it exposes and addresses what the sources overlook, misinterpret, misrepresent, neglect, say something that is contentious, about which they are outdated);

presents arguments and counter-arguments, evidence and counter-evidence about an issue;

presents arguments and counter-arguments, evidence and counter-evidence about an issue;

reveals similarities and differences between authors, about the same issue;

reveals similarities and differences between authors, about the same issue;

must state its purposes, methods of working, organization and how it will move to a conclusion, i.e. what it will do, what it will argue, what it will show, what it will conclude, and how this links into or informs the subsequent research project;

must state its purposes, methods of working, organization and how it will move to a conclusion, i.e. what it will do, what it will argue, what it will show, what it will conclude, and how this links into or informs the subsequent research project;

must state its areas of focus, maybe including a statement of the problem or issue that is being investigated, the hypothesis that the research will test, the themes or topics to be addressed, or the thesis that the research will defend;

must state its areas of focus, maybe including a statement of the problem or issue that is being investigated, the hypothesis that the research will test, the themes or topics to be addressed, or the thesis that the research will defend;

is a springboard into, and foundation for, all areas and stages of the research in question: purpose, foci, research questions, methodology, data analysis, discussion and conclusions;

is a springboard into, and foundation for, all areas and stages of the research in question: purpose, foci, research questions, methodology, data analysis, discussion and conclusions;

must be conclusive;

must be conclusive;

must be focused yet comprehensive in its coverage of relevant issues;

must be focused yet comprehensive in its coverage of relevant issues;

must present both sides of an issue or argument;

must present both sides of an issue or argument;

should address theories, models (where relevant), empirical research, methodological materials, substantive issues, concepts, content and elements of the field in question;

should address theories, models (where relevant), empirical research, methodological materials, substantive issues, concepts, content and elements of the field in question;

must include and draw on many sources and types of written material and kinds of data, for example Box 7.2.

must include and draw on many sources and types of written material and kinds of data, for example Box 7.2.

For a fuller treatment of conducting and reporting a literature review we refer readers to Ridley (2008).

BOX 7.2 TYPES OF INFORMATION IN A LITERATURE REVIEW

Books (hard copy and e-books)

Articles in journals: academic and professional (hard copy and online)

Empirical and non-empirical research

Reports: from governments, NGOs, organizations, influential associations

Policy documents: from governments, organizations, ‘think-tanks’

Public and private records

Research papers and reports, e.g. from research centres, research organizations

Theses and dissertations

Manuscripts

Databases (searchable collections of records, electronic or otherwise)

Conference papers – local, regional, national, international

Primary sources (original, first-hand, contemporary source materials such as documents, speeches, diaries and personal journals, letters, emails, autobiographies, memoirs, public records and reports, emails and other correspondence, interview and raw research data, minutes and agendas of meetings, memoranda, proceedings of meetings, communiqués, charters, acts of parliament or government, legal documents, pamphlets, witness statements, oral histories, unpublished works, patents, websites, video or film footage, photographs, pictures and other visual materials, audio-recordings, artefacts, clothing or other evidence. These are usually produced directly at the time of, close to, or in connection with, the research in question.)

Online databases

Electronic journals or media

Secondary sources (second-hand, non-original materials, materials written about primary sources, or materials based on sources that were originally elsewhere or which other people have written or gathered, where primary materials have been worked on or with, described, reported, analysed, discussed, interpreted, evaluated, summarized or commented upon, or which are at one remove from the primary sources, or which are written some time after the event, e.g. encyclopedias, dictionaries, newspaper articles, reports, critiques, commentaries, digests, textbooks, research syntheses, meta-analyses, research reviews, histories, summaries, analyses, magazine articles, pamphlets, biographies, monographs, treatises, works of criticism (e.g. literary or political))

Tertiary sources (distillations, collections or compilations of primary and secondary sources, e.g. almanacs, bibliographies, catalogues, dictionaries, encyclopedias, facts books, directories, indexes, abstracts, bibliographies, manuals, guidebooks, handbooks, chronologies).

The storage and retrieval of research data on the internet play an important role not only in keeping researchers abreast of developments across the world, but also in providing access to data which can inform literature searches to establish construct and content validity in their own research. Indeed, some kinds of research are essentially large-scale literature searches (e.g. the research papers published in the journals Review of Educational Research and Review of Research in Education, and materials from the Evidence and Policy and Practice Information and Co-ordinating Centre (EPPI-Centre) at the University of London (http://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/cms/) and the What Works Clearinghouse in the United States (http://ies.ed.gov/ncee/wwc/)). Online journals, abstracts and titles enable researchers to keep up with the cutting edge of research and to conduct a literature search of relevant material on their chosen topic. Websites and email correspondence enable networks and information to be shared. For example, researchers wishing to gain instantaneous global access to literature and recent developments in research associations can reach Australia, East Asia, the UK and America in a matter of seconds through such websites as:

www.aera.net (the website of the American Educational Research Association);

www.eduref.org/ (The Educators’ Reference Desk, the source of ERIC in the USA (publications of the American Educational Research Association));

www.acer.edu.au/index2.html (the website of the Australian Council for Educational Research);

www.bera.ac.uk (the website of the British Educational Research Association);

http://scre.ac.uk (the website of the Scottish Council for Research in Education);

www.scre.ac.uk/is/webjournals.html (the website of the Scottish Council for Research in Education’s links to electronic journals);

www.eera.ac.uk/ (the website of the European Educational Research Association);

www.cem.dur.ac.uk (the website of the Curriculum Evaluation and Management Centre, amongst the largest monitoring centres of its kind in the world);

www.nfer.ac.uk (the website of the National Foundation for Educational Research in the UK);

www.fed.cuhk.edu.hk/~hkera (the website of the Hong Kong Educational Research Association);

www.wera-web.org/index.html (the website of the Washington Educational Research Association);

www.msstate.edu/org/msera/msera.html (the website of the mid-South Educational Research Association, a very large regional association in the USA);

www.esrc.ac.uk (the website of the Economic and Social Research Council in the UK).

Researchers wishing to access online journal indices and references for published research results (rather than to specific research associations as in the websites above) have a variety of websites which they can visit, for example:

www.leeds.ac.uk/bei (to gain access to the British Education Index);

http://brs.leeds.ac.uk/~beiwww/beid.html (the website for online searching of the British Educational Research Association’s archive);

www.routledge.com:9996/routledge/journal/er.html (the website of an international publisher that provides information on all its research articles);

www.sagepub.co.uk (Sage publications);

www.intute.ac.uk (database that gives access to several other sources of information);

www.tandf.co.uk/journals/ (Taylor and Francis website of journals);

www.tandf.co.uk/era/ (Educational Research Abstracts Online, an alerting service from the publisher Taylor and Francis);

http://bubl.ac.uk (a national information service in the UK, provided for the higher education community);

www.gashe.ac.uk (data for the archives of Scottish Higher Education);

www.sosig.ac.uk (the Social Science Information Gateway, providing access to worldwide resources and information);

http://sosig.ac.uk/social_science_general/social_science_methodology) (the Social Science Information Gateway’s sections on research methods, both quantitative and qualitative);

http://wos.mimas.ac.uk (the website of the Web of Science, that, amongst other functions, provides access to the Social Science Citation Index, the Science Citation Index and the Arts and Humanities Citation Index);

www.statistics.gov.uk (the UK’s home site for national statistics);

www.dcsf.gov.uk/ (the UK Government’s Department for Children, Schools and Families);

www.communities.gov.uk/corporate/ (UK website for Communities and Local Government);

www.hesa.ac.uk/ (the UK’s Higher Education Statistics Agency);

www.civilservice.gov.uk/my-civil-service/networks/pro-fessional/gsr/index.aspx (the UK Government’s Social Research website);

http://surveynet.ac.uk/sqb/ (the Survey Question Bank for the UK’s Economic and Social Research Council);

www.esds.ac.uk/ (the UK’s Economic and Social Data Service);

www.unesco.org/new/en/unesco/ (UNESCO homepage);

www.oecd.org/education (homepage of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development that can direct researchers to the statistics databases);

www.coe.int/T/E/Cultural_Co-operation/education/ (The Council of Europe’s education homepage);

www.cessda.org/ (The Council of European Social Science Data Archive);

www.data-archive.ac.uk/ (The UK Data Archive);

http://europa.eu/index_en.htm (the gateway site to the European Union);

http://nces.ed.gov/ (the Unites States National Center for Educational Statistics);

http://worldbank.org (World Bank, that is a gateway to its data and statistics section).

With regard to searching libraries, there are several useful websites:

www.loc.gov (the United States Library of Congress);

www.lcweb.loc.gov/z3950 (gateway to US libraries);

www.libdex.com/ (the Library Index website, linking to 18,000 libraries);

www.copac.ac.uk (this enables researchers to search major UK libraries);

http://catalogue.bl.uk/F/?func=file&fle_name=login-bllist (the British Library integrated catalogue);

www.bl.uk/reshelp/findhelprestype/catblhold/all/allcat.html (all the British Library’s online catalogues);

http://vlib.org/ (the Virtual Library, and provides online resources).

For checking what is in print, www.booksinprint.com provides a comprehensive listing of current books in print, whilst www.bibliofind.com is a site of old, out-of-print and rare books. The website www.lights.com links researchers to some 6,000 publishers.

Additional useful websites are:

www.nap.edu (the website of the National Academies Press), and www.nap.edu/topics.php?topic=282 (the National Academies Press, Education Section);

www.educationindex.com/ and www.shawmultimedia.com/links2.html (centres for the provision of free educational materials and related websites);

www.ipl.org/ (this is the website of the merged internet Public Library and the Librarians’ Internet Index);

www.ncrel.org/ (the website of the North Central Regional Educational Laboratories, an organization providing a range of educational resources);

www.sedl.org/ (the website of the Southwest Educational Development Laboratory, an organization providing a range of educational resources).

Most journals provide access to abstracts free online, though access to the full article is usually by subscription only. Providers of online journals include, for example (in alphabetical order):

Bath Information and Data Services (BIDS) (www.bids.ac.uk);

EBSCO (www.ebsco.com)

Elsevier (www.elsevier.com)

Emerald (www.emeraldinsight.com)

FirstSearch (www.oclc.org)

Ingenta (www.ingenta.com)

JSTOR (www.jstor.org)

Kluweronline (www.kluweronline.com)

Northern Light (www.northernlight.com)

ProQuest (www.proquest.com and www.bellhowell, infolearning.com.proquest)

ProQuest Digital Dissertations and Theses (www.proquest.com/en-US/catalogs/databases/detail/pqdt.shtml)

Science Direct (www.sciencedirect.com)

Swets (www.swets.com)

Web of Science (now Web of Knowledge) (http://wok.mimas.ac.uk/

For theses, Aslib Index to Theses is useful (www.theses.com) and the Networked Digital Library of Theses and Dissertations can be located at www.theses.org and www.ndltd.org/find. Some major government websites also have a free alerting service (e.g. OFSTED).

Researchers who do not possess website addresses have at their disposal a variety of search engines to locate them. At the time of writing some widely used engines are (in alphabetical order):

AltaVista (www.altavista.com);

AOL Search (www.search.aol.com);

Ask Jeeves (www.askjeeves.com);

Direct Hit (www.directhit.com);

Excite (www.Excite.com);

Fast Search (www.alltheweb.com);

Go To (www.goto.com);

Google (www.google.com);

Google Scholar (http:/scholar.google.com);

HotBot (www.hotbot.com);

Internet Explorer (www.microsoft.com);

Lycos (www.Lycos.com);

Metacrawler (www.metacrawler.com);

MSN Search (www.msn.com);

Netscape Navigator (www.netscape.com);

Northern Light (www.northernlight.com);

Yahoo (www.yahoo.com).

There are very many more. All of these search engines enable researchers to conduct searches by keywords. Some of these are parallel search engines (which will search several single search engines at a time), and file search engines (which will search files across the world).

When searching the internet it is useful to keep in mind several points:

placing words, phrases or sentences inside inverted commas (“. . .”) will keep those words together and in that order in searching for material; this helps to reduce an overload of returned sites;

placing words, phrases or sentences inside inverted commas (“. . .”) will keep those words together and in that order in searching for material; this helps to reduce an overload of returned sites;

placing an asterisk (*) after a word or part of a word will return sites that start with that term but which have different endings, e.g. teach* will return sites on teach, teaching, teacher;

placing an asterisk (*) after a word or part of a word will return sites that start with that term but which have different endings, e.g. teach* will return sites on teach, teaching, teacher;

placing a tilde mark (~) before a word will identify similar words to that which have been entered, e.g. ~English teaching will return sites on English language as well as English teaching;

placing a tilde mark (~) before a word will identify similar words to that which have been entered, e.g. ~English teaching will return sites on English language as well as English teaching;

placing the words and, not, or between phrases or words will return websites where the command indicated in each one of these words is addressed.

placing the words and, not, or between phrases or words will return websites where the command indicated in each one of these words is addressed.

Finding research information, where not available from databases and indices on CD-ROMs, is often done through the internet by trial and error and serendipity, identifying the key words singly or in combination (between inverted commas). The system of ‘bookmarking’ websites enables rapid retrieval of these websites for future reference; this is perhaps essential, as some internet connections are slow, and a vast amount of material on it is, at best, unhelpful!

The use of the internet for educational research will require an ability to evaluate websites. The internet is a vast store of disorganized and largely unvetted material, and researchers will need to be able to ascertain quite quickly how far the web-based material is appropriate. There are several criteria for evaluating websites, including the following (e.g. Tweddle et al., 1998; Rodrigues and Rodriques, 2000):

the purpose of the site, as this will enable users to establish its relevance and appropriateness;

the purpose of the site, as this will enable users to establish its relevance and appropriateness;

the authority and authenticity of the material, which should both be authoritative and declare its sources;

the authority and authenticity of the material, which should both be authoritative and declare its sources;

the content of the material – its up-to-dateness, relevance and coverage;

the content of the material – its up-to-dateness, relevance and coverage;

the credibility and legitimacy of the material (e.g. is it from a respected source or institution);

the credibility and legitimacy of the material (e.g. is it from a respected source or institution);

the correctness, accuracy, completeness and fairness of the material;

the correctness, accuracy, completeness and fairness of the material;

the objectivity and rigour of the material being presented and/or discussed.

the objectivity and rigour of the material being presented and/or discussed.

In evaluating educational research materials on the web, researchers and teachers can ask themselves several questions (Hartley et al., 1997):

Is the author identified?

Is the author identified?

Does the author establish her/his expertise in the area, and institutional affiliation?

Does the author establish her/his expertise in the area, and institutional affiliation?

Is the organization reputable?

Is the organization reputable?

Is the material referenced; does the author indicate how the material was gathered?

Is the material referenced; does the author indicate how the material was gathered?

What is the role that this website is designed to play (e.g. to provide information, to persuade)?

What is the role that this website is designed to play (e.g. to provide information, to persuade)?

Is the material up to date?

Is the material up to date?

Is the material free from biases, personal opinions and offence?

Is the material free from biases, personal opinions and offence?

How do we know that the author is authoritative on this website?

How do we know that the author is authoritative on this website?

It is important for the researcher to keep full bibliographic data of the website material used, including the date on which it was retrieved and the website address.

With these preliminary comments, let us turn to the four main areas of the framework for planning research.

Decisions in this field are strategic; they set the general nature of the research, and the questions that researchers may need to consider are:

Who wants the research?

Who wants the research?

Who will receive the research/who is it for?

Who will receive the research/who is it for?

Who are the possible/likely audiences of the research?

Who are the possible/likely audiences of the research?

What powers do the recipients of the research have?

What powers do the recipients of the research have?

What are the general aims and purposes of the research?

What are the general aims and purposes of the research?

What are the main priorities for and constraints on the research?

What are the main priorities for and constraints on the research?

Is access realistic?

Is access realistic?

What are the timescales and time frames of the research?

What are the timescales and time frames of the research?

Who will own the research?

Who will own the research?

At what point will the ownership of the research pass from the participants to the researcher and from the researcher to the recipients of the research?

At what point will the ownership of the research pass from the participants to the researcher and from the researcher to the recipients of the research?

Who owns the data?

Who owns the data?

What ethical issues are to be faced in undertaking the research?

What ethical issues are to be faced in undertaking the research?

What resources (e.g. physical, material, temporal, human, administrative) are required for the research?

What resources (e.g. physical, material, temporal, human, administrative) are required for the research?

It can be seen that decisions here establish some key parameters of the research, including some political decisions (for example, on ownership and on the power of the recipients to take action on the basis of the research). At this stage the overall feasibility of the research will be addressed.

If the preceding orienting decisions are strategic then decisions in this field are tactical; they establish the practicalities of the research, assuming that, generally, it is feasible (i.e. that the orienting decisions have been taken). Decisions here include addressing such questions as:

What are the specific purposes of the research?

What are the specific purposes of the research?

Does the research need research questions?

Does the research need research questions?

How are the general research purposes and aims operationalized into specific research questions?

How are the general research purposes and aims operationalized into specific research questions?

What are the specific research questions?

What are the specific research questions?

What needs to be the focus of the research in order to answer the research questions?

What needs to be the focus of the research in order to answer the research questions?

What is the main methodology of the research (e.g. a quantitative survey, qualitative research, an ethnographic study, an experiment, a case study, a piece of action research, etc.)?

What is the main methodology of the research (e.g. a quantitative survey, qualitative research, an ethnographic study, an experiment, a case study, a piece of action research, etc.)?

Does the research need mixed methods, and if so, is the mixed methods research a parallel, sequential, combined or hierarchical approach (see Chapter 1)?

Does the research need mixed methods, and if so, is the mixed methods research a parallel, sequential, combined or hierarchical approach (see Chapter 1)?

Are mixed methods research questions formulated where appropriate?

Are mixed methods research questions formulated where appropriate?

How will validity and reliability be addressed?

How will validity and reliability be addressed?

What kinds of data are required?

What kinds of data are required?

From whom will data be acquired (i.e. sampling)?

From whom will data be acquired (i.e. sampling)?

Where else will data be available (e.g. documentary sources)?

Where else will data be available (e.g. documentary sources)?

How will the data be gathered (i.e. instrumentation)?

How will the data be gathered (i.e. instrumentation)?

Who will undertake the research?

Who will undertake the research?

Chapter 6 indicated that there are many different kinds of research questions that derive from different purposes of the research. For example research questions may seek:

to describe what a phenomenon is and what is, or was, happening in a particular situation (e.g. ethnographies, case studies, complexity theory-based studies, surveys);

to describe what a phenomenon is and what is, or was, happening in a particular situation (e.g. ethnographies, case studies, complexity theory-based studies, surveys);

to predict what will happen (e.g. experimentation, causation studies, research syntheses);

to predict what will happen (e.g. experimentation, causation studies, research syntheses);

to investigate what should happen (e.g. evaluative research, policy research, ideology critique, participatory research);

to investigate what should happen (e.g. evaluative research, policy research, ideology critique, participatory research);

to examine the effects of an intervention (e.g. experimentation, ex post facto studies, case studies, action research, causation studies);

to examine the effects of an intervention (e.g. experimentation, ex post facto studies, case studies, action research, causation studies);

to examine perceptions of what is happening (e.g. ethnography, survey);

to examine perceptions of what is happening (e.g. ethnography, survey);

to compare the effects of an intervention in different contexts (experimentation, comparative studies);

to compare the effects of an intervention in different contexts (experimentation, comparative studies);

to develop, implement, monitor and review an intervention (e.g. participatory research, action research) (cf. Newby, 2010: 66).

to develop, implement, monitor and review an intervention (e.g. participatory research, action research) (cf. Newby, 2010: 66).

Indeed research questions can ask ‘what’, ‘who’, ‘why’, ‘when’, where’, and ‘how’ (cf. Newby, 2010: 65–6). In all these the task of the researcher is to turn the general purposes of the research into actual practice, i.e. to operationalize the research.

The process of operationalization is critical for effective research. Operationalization means specifying a set of operations or behaviours that can be measured, addressed or manipulated. What is required here is translating a very general research aim or purpose into specific, concrete questions to which specific, concrete answers can be given. The process moves from the general to the particular, from the abstract to the concrete. Thus the researcher breaks down each general research purpose or general aim into more specific research purposes and constituent elements, continuing the process until specific, concrete questions have been reached to which specific answers can be provided. Two examples of this are provided below.

Let us imagine that the overall research aim is to ascertain the continuity between primary and secondary education (Morrison, 1993: 31–3). This is very general, and needs to be translated into more specific terms. Hence the researcher might deconstruct the term ‘continuity’ into several components, for example experiences, syllabus content, teaching and learning styles, skills, concepts, organizational arrangements, aims and objectives, ethos, assessment. Given the vast scope of this the decision is taken to focus on continuity of pedagogy. This is then broken down into its component areas:

the level of continuity of pedagogy;

the level of continuity of pedagogy;

the nature of continuity of pedagogy;

the nature of continuity of pedagogy;

the degree of success of continuity of pedagogy;

the degree of success of continuity of pedagogy;

the responsibility for continuity;

the responsibility for continuity;

record keeping and documentation of continuity;

record keeping and documentation of continuity;

resources available to support continuity.

resources available to support continuity.

The researcher might take this further into investigating: the nature of the continuity (i.e. the provision of information about continuity); the degree of continuity (i.e. a measure against a given criterion); the level of success of the continuity (i.e. a judgement). An operationalized set of research questions, then, might be:

How much continuity of pedagogy is occurring across the transition stages in each curriculum area? What kind of evidence is required to answer this question? On what criteria will the level of continuity be decided?

How much continuity of pedagogy is occurring across the transition stages in each curriculum area? What kind of evidence is required to answer this question? On what criteria will the level of continuity be decided?

What pedagogical styles operate in each curriculum area? What are the most frequent and most preferred? What is the balance of pedagogical styles? How is pedagogy influenced by resources? To what extent is continuity planned and recorded? On what criteria will the nature of continuity be decided? What kind of evidence is required to answer this question?

What pedagogical styles operate in each curriculum area? What are the most frequent and most preferred? What is the balance of pedagogical styles? How is pedagogy influenced by resources? To what extent is continuity planned and recorded? On what criteria will the nature of continuity be decided? What kind of evidence is required to answer this question?

On what aspects of pedagogy does planning take place? By what criteria will the level of success of continuity be judged? Over how many students/teachers/curriculum areas will the incidence of continuity have to occur for it to be judged successful? What kind of evidence is required to answer this question?

On what aspects of pedagogy does planning take place? By what criteria will the level of success of continuity be judged? Over how many students/teachers/curriculum areas will the incidence of continuity have to occur for it to be judged successful? What kind of evidence is required to answer this question?

Is continuity occurring by accident or design? How will the extent of planned and unplanned continuity be gauged? What kind of evidence is required to answer this question?

Is continuity occurring by accident or design? How will the extent of planned and unplanned continuity be gauged? What kind of evidence is required to answer this question?

Who has responsibility for continuity at the transition points? What is being undertaken by these people?

Who has responsibility for continuity at the transition points? What is being undertaken by these people?

How are records kept on continuity in the schools? Who keeps these records? What is recorded? How frequently are the records updated and reviewed? What kind of evidence is required to answer this question?

How are records kept on continuity in the schools? Who keeps these records? What is recorded? How frequently are the records updated and reviewed? What kind of evidence is required to answer this question?

What resources are there to support continuity at the point of transition? How adequate are these resources? What kind of evidence is required to answer this question?

What resources are there to support continuity at the point of transition? How adequate are these resources? What kind of evidence is required to answer this question?

It can be seen that these questions, several in number, have moved the research from simply an expression of interest (or a general aim) into a series of issues that lend themselves to being investigated in concrete terms. This is precisely what we mean by the process of operation-alization. It is now possible to identify not only the specific questions to be posed, but also the instruments that might be needed to acquire data to answer them (e.g. semi-structured interviews, rating scales on questionnaires or documentary analysis). By this process of oper-ationalization we thus make a general purpose amenable to investigation, e.g. by measurement (Rose and Sullivan, 1993: 6) or some other means. The number of oper-ationalized research questions is large here, and may have to be reduced to maybe four or five at most, in order to render the research manageable.

An alternative way of operationalizing research questions takes the form of hypothesis raising and hypothesis testing. A ‘good’ hypothesis has several features:

It is clear on whether it is directional or non-directional: a directional hypothesis states the kind or direction of difference or relationship between two conditions or two groups of participants (e.g. students’ performance increases when they are intrinsically motivated). A non-directional hypothesis simply predicts that there will be a difference or relationship between two conditions or two groups of participants (e.g. there is a difference in students’ performance according to their level of intrinsic motivation), without stating whether the difference, for example, is an increase or a decrease. (For statistical purposes, a directional hypothesis requires a one-tailed test whereas a non-directional hypothesis uses a two-tailed test, see Part 5.) Directional hypotheses are often used when past research, predictions, or theory suggest that the findings may go in a particular direction, whereas non-directional hypotheses are used when past research or theory is unclear or contradictory or where prediction is not possible, i.e. where the results are more open-ended.

It is clear on whether it is directional or non-directional: a directional hypothesis states the kind or direction of difference or relationship between two conditions or two groups of participants (e.g. students’ performance increases when they are intrinsically motivated). A non-directional hypothesis simply predicts that there will be a difference or relationship between two conditions or two groups of participants (e.g. there is a difference in students’ performance according to their level of intrinsic motivation), without stating whether the difference, for example, is an increase or a decrease. (For statistical purposes, a directional hypothesis requires a one-tailed test whereas a non-directional hypothesis uses a two-tailed test, see Part 5.) Directional hypotheses are often used when past research, predictions, or theory suggest that the findings may go in a particular direction, whereas non-directional hypotheses are used when past research or theory is unclear or contradictory or where prediction is not possible, i.e. where the results are more open-ended.

It is written in a testable form, i.e. in a way that makes it clear how the researcher will design an experiment or survey to test the hypothesis, e.g. people perform a mathematics task better when there is silence in the room than when there is not. The concept of interference by noise has been operationalized in order to produce a testable hypothesis.

It is written in a testable form, i.e. in a way that makes it clear how the researcher will design an experiment or survey to test the hypothesis, e.g. people perform a mathematics task better when there is silence in the room than when there is not. The concept of interference by noise has been operationalized in order to produce a testable hypothesis.

It is written in a form that can yield measurable results.

It is written in a form that can yield measurable results.

For example, in the hypothesis people work better in quiet rather than noisy conditions it is important to define the operations for ‘work better’, ‘quiet’ and ‘noisy’. Here ‘perform better’ might mean ‘obtain a higher score on the mathematics test’, ‘quiet’ might mean ‘silence’, and ‘noisy’ might mean ‘having music playing’. Hence the fully operationalized hypothesis might be people obtain a higher score on a mathematics test when tested when there is silence rather than when there is music playing. One can see here that the score is measurable and that there is zero noise, i.e. a measure of the noise level.

In conducting research using hypotheses one has to be prepared to use several hypotheses (Muijs, 2004: 16) in order to catch the complexity of the phenomenon being researched, and not least because mediating variables have to be included in the research. For example, the degree of ‘willing cooperation’ (dependent variable) in an organization’s staff is influenced by ‘professional leadership’ (independent variable) and the ‘personal leadership qualities of the leader’ (mediating variable) which needs to be operationalized more specifically, of course.

There is also the need to consider the null hypothesis and the alternative hypothesis (discussed in Part 5) in research that is cast into a hypothesis testing model. The null hypothesis states that, for example, there is no relationship between two variables, or that there has been no difference in participants’ scores on a pre-test and a post-test of history, or that there is no difference between males and females in respect of their science examination results. The alternative hypothesis states, for example: there is a correlation between motivation and performance; there is a difference between males’ and females’ scores on science; there is a difference between the pre-test and post-test scores on history. The alternative hypothesis is often supported when the null hypothesis is ‘not supported’, i.e. if the null hypothesis is not supported then the alternative hypothesis is. The two kinds of hypothesis are usually written thus:

H0: the null hypothesis

H1: the alternative hypothesis

We address the hypothesis-testing approach fully in Part 5.

In planning research it is important to clarify a distinction that needs to be made between methodology and methods, approaches and instruments, styles of research and ways of collecting data. Several of the later chapters of this book are devoted to specific instruments for collecting data, e.g.

interviews

interviews

questionnaires

questionnaires

observation

observation

tests

tests

accounts

accounts

biographies and case studies

biographies and case studies

role playing

role playing

simulations

simulations

personal constructs.

personal constructs.

The decision on which instrument (method) to use frequently follows from an important earlier decision on which kind (methodology) of research to undertake, for example:

a survey

a survey

an experiment

an experiment

an in-depth ethnography

an in-depth ethnography

action research

action research

case study research

case study research

testing and assessment.

testing and assessment.

Subsequent chapters of this book set out each of these research styles, their principles, rationales and purposes, and the instrumentation and data types that seem suitable for them. For conceptual clarity it is possible to set out some key features of these models (Table 7.3). It is intended that, when decisions have been reached on the stage of research design and methodology, a clear plan of action will have been prepared. To this end, considering models of research might be useful (Morrison, 1993).

The prepared researcher will need to consider how the data will be analysed. This is very important, as it has a specific bearing on the form of the instrumentation. For example, a researcher will need to plan the layout and structure of a questionnaire survey very carefully in order to assist data entry for computer reading and analysis; an inappropriate layout may obstruct data entry and subsequent analysis by computer. The planning of data analysis will need to consider:

What needs to be done with the data when they have been collected – how will they be processed and analysed?

What needs to be done with the data when they have been collected – how will they be processed and analysed?

How will the results of the analysis be verified, cross-checked and validated?

How will the results of the analysis be verified, cross-checked and validated?

Decisions will need to be taken with regard to the statistical tests that will be used in data analysis as this will affect the layout of research items (for example in a questionnaire), and the computer packages that are available for processing quantitative and qualitative data, e.g. SPSS and N-Vivo respectively. For statistical processing the researcher will need to ascertain the level of data being processed – nominal, ordinal, interval or ratio (discussed in Chapter 34). Part 5 addresses issues of data analysis and which statistics to use: the choice is not arbitrary (Siegel, 1956; Cohen and Holli-day, 1996; Hopkins et al., 1996). For qualitative data analysis researchers have at their disposal a range of techniques, for example:

coding and content analysis of field notes (Miles and Huberman, 1984);

coding and content analysis of field notes (Miles and Huberman, 1984);

cognitive mapping (Jones, 1987; Morrison, 1993);

cognitive mapping (Jones, 1987; Morrison, 1993);

seeking patterning of responses;

seeking patterning of responses;

looking for causal pathways and connections (Miles and Huberman, 1984);

looking for causal pathways and connections (Miles and Huberman, 1984);

presenting cross-site analysis (Miles and Huberman, 1984);

presenting cross-site analysis (Miles and Huberman, 1984);

case studies;

case studies;

personal constructs;

personal constructs;

narrative accounts;

narrative accounts;

action research analysis;

action research analysis;

analytic induction (Denzin, 1970);

analytic induction (Denzin, 1970);

constant comparison and grounded theory (Glaser and Strauss, 1967);

constant comparison and grounded theory (Glaser and Strauss, 1967);

discourse analysis (Stillar, 1998);

discourse analysis (Stillar, 1998);

biographies and life histories (Atkinson, 1998).

biographies and life histories (Atkinson, 1998).

The criteria for deciding which forms of data analysis to undertake are governed both by fitness for purpose and legitimacy – the form of data analysis must be appropriate for the kinds of data gathered. For example it would be inappropriate to use certain statistics with certain kinds of numerical data (e.g. using means on nominal data), or to use causal pathways on unrelated cross-site analysis.

As with the stage of planning data analysis, the prepared researcher will need to consider the form of the reporting of the research and its results, giving due attention to the needs of different audiences (for example an academic audience may require different contents from a wider professional audience and, a fortiori, from a lay audience). Decisions here will need to consider:

How to write up and report the research.

How to write up and report the research.

When to write up and report the research (e.g. ongoing or summative).

When to write up and report the research (e.g. ongoing or summative).

How to present the results in tabular and/or written-out form.

How to present the results in tabular and/or written-out form.

How to present the results in non-verbal forms.

How to present the results in non-verbal forms.

To whom to report (the necessary and possible audiences of the research).

To whom to report (the necessary and possible audiences of the research).

How frequently to report.

How frequently to report.

For an example of setting out a research report, see the accompanying website.

In planning a piece of research, the range of questions to be addressed can be set into a matrix. Table 7.4 provides such a matrix, in the left-hand column of which are the questions which figure in the four main areas set out so far:

1 orienting decisions;

2 research design and methodology;

3 data analysis;

4 presenting and reporting the results.

Questions 1–10 are the orienting decisions, questions 11–22 concern the research design and methodology, questions 23–4 cover data analysis, and questions 25–30 deal with presenting and reporting the results. Within each of the 30 questions there are several subquestions which research planners may need to address. For example, within question 5 (‘What are the purposes of the research?’) the researcher would have to differentiate major and minor purposes, explicit and maybe implicit purposes, whose purposes are being served by the research, and whose interests are being served by the research. An example of these sub-issues and problems is contained in the second column.

At this point the planner is still at the divergent phase of the research planning, dealing with planned possibilities (Morrison, 1993: 19), opening up the research to all facets and interpretations. In the column headed ‘decisions’ the research planner is moving towards a convergent phase, where planned possibilities become visible within the terms of constraints available to the researcher. To do this the researcher has to move down the column marked ‘decisions’ to see how well the decision which is taken in regard to one issue/question fits in with the decisions in regard to other issues/questions. For one decision to fit with another, four factors must be present:

1 all the cells in the ‘decisions’ column must be coherent – they must not contradict each other;

2 all the cells in the ‘decisions’ column must be mutually supporting;

3 all the cells in the ‘decisions’ column must be practicable when taken separately;

4 all the cells in the ‘decisions’ column must be practicable when taken together.