1.

When we visited my grandparents’ house by the bamboo grove, my brother Philip and I slept in a big double bed in the attic, surrounded by musty boxes filled with my mother’s high school textbooks. On hot summer nights, the attic was stifling. Big trucks barreled down U.S. 1, their high-pitched approach abruptly waning to a long, tapering whine. “The Doppler effect,” our father whispered, as he tucked us in for the long night. We woke up feeling feverish in the predawn hours.

There was a metal bedpan under the bed—a relic from the years when a dilapidated outhouse, down a stone pathway toward the snake-infested barn, was the only toilet. The floral design on the bedpan was meant to evoke the sophisticated delicacy of blue-and-white porcelain. We refused to use it, preferring to make the long journey down two flights of stairs and through the dark hallway to the enclosed front porch, which smelled in all seasons of ripening peaches. On one side of the porch, my grandfather had added a modern bathroom with a claw-foot tub.

Halfway down the darkened hallway, opposite the door to my grandparents’ bedroom, was a little wooden table for the old-fashioned telephone, a squat lacquered Buddha in black. Next to the telephone was an earthenware pitcher, dusky orange, with a large handle like an ear swooping down from the rim. To me, the telephone with its oversize receiver and the pitcher with its oversize handle seemed like two potbellied divinities listening to whispered words not meant for children’s ears.

I knew one thing that the pitcher and the telephone had heard in the hallway; it was one of the first “grown-up things” I learned about as a child. It involved a handsome young man from my grandparents’ church. He had wanted to be a pilot during the war and had wanted to marry a girl his family disapproved of. He had been doubly disappointed. The woman he eventually married instead was a stickler for the proper way to do things. Once she complained to my grandmother that her husband was seeing other women. “What do you expect,” my grandmother said, “when you turn your back on him at night?” Then she pointed to her own double bed of sturdy mahogany. “That,” she said, “is where marriages succeed or fail!”

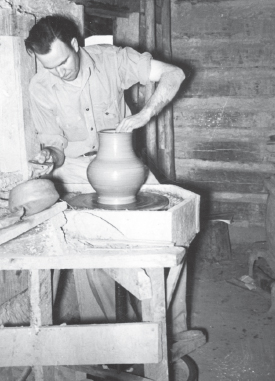

I knew something else about the orange pitcher on the telephone table. I knew that it was a Jugtown pot. My parents had taken me to Jugtown, a small folk pottery a half hour’s drive west of Cameron on quiet country roads, when I was six or seven years old. I had seen the harnessed old mule outside, walking around and around in a circle, turning the mill that ground the local clay, dug from the red earth nearby. I had watched Ben Owen, the potter there, standing at the turning wheel. A handsome man, he pulled a vase with his iron-strong fingers from a lump of centered clay.

One afternoon, I watched Ben Owen “milking” handles for a row of pitchers just like the one in the dark hallway by the telephone. He would take a lump of clay in his left hand and, with his curled wet right hand, gently coax an udder of clay downward. He pushed the upper end onto the rim of the pitcher, allowing the clay to bend down from its own weight, like a swooping question mark, into the graceful form of a handle. Then, he pressed

Ben Owen at Jugtown

the lower end to the pitcher with his thumb, leaving an imprint like a signature.

2.

I had grown up with Jugtown things. My favorite cup back home in Indiana was a Jugtown teacup, a little orange thing with a chipped rim and a smooth handle. Our sugar bowl and creamer were Ben Owen pots, salt-glazed and pebbled gray with cobalt blue decorations around the rim. These were the traditional shapes of North Carolina pottery, made in the Piedmont for a century and more. My grandparents’ pitcher on the telephone table was glazed with orange lead and speckled with random spots of black iron that had oxidized during the long firing in the half-buried “groundhog” kiln. The glaze was known as tobacco spit. Only now, writing down the familiar name, do I see what it means: the color of chewing tobacco spat out on the ground.

A work of pottery like my grandparents’ orange pitcher lives in two different worlds. It is beautiful to look at, and Jugtown pots during the last fifty years have migrated steadily from private homes into museums. But these pots were also made for use, for keeping the iced tea cold. The German philosopher Georg Simmel, in a beautiful essay called “The Handle,” wrote about this double life. A pottery vessel, he wrote, “unlike a painting or statue, is not intended to be insulated and untouchable but is meant to fulfill a purpose—if only symbolically. For it is held in the hand and drawn into the movement of practical life. Thus the vessel stands in two worlds at one and the same time.” The handle marks the journey from one world to the other; it is the suspension bridge from the world of art to the world of use.

If I close my eyes, I can visualize the old black telephone and the tobacco-spit pitcher sitting side by side, like an old married couple, on my grandparents’ table. Both of them bring things that are far away into proximity. The telephone abolishes distance with a quick ring, a hasty grasp of the receiver, and a hurried hello. The pitcher invites a deeper, slower nearness, with the hand holding the gradually warming handle. The ear-shaped handle of the pitcher opens into other worlds and other voices, deep in the past.

The story of Jugtown, as I first heard it in outline from my mother, had a certain romance. Two young dreamers from Raleigh, North Carolina, my mother’s birthplace, had come up with the idea of establishing a folk pottery in the clay-rich Piedmont. James Busbee, a well-heeled descendant of Raleigh lawyers, had artistic tastes. He studied at the National Academy of Design and the Art Students’ League in New York, changed his name from James to the more romantic Jacques, and pursued a career as a portrait painter. His wife, Julia, changed her name to Juliana, and worked as an illustrator. After their marriage in 1910, the Busbees became interested in folk crafts. As chair of the art division of the Federation of Women’s Clubs of North Carolina, Juliana promoted traditional weaving and basketry. Jacques began collecting native pottery, especially the low-fired earthenware and more durable stoneware of the North Carolina Piedmont west of Raleigh.

One reason for the sheer concentration of potters in central North Carolina, where Busbee began his search, is the abundance of excellent potting clays. In its purest form, clay is made of alumina (bauxite), silica (sand), and chemically bonded water. But in the wild, so to speak, it is generally found mixed with other ingredients, so that different clays have different characteristics, like wine grapes grown in different regions. Clay comes in two major kinds: residual and sedimentary. A residual clay stays where it was formed; it resides there. The English word clay comes from the German kleben, meaning “to stick to or cling” and is related to the word cleave. The snow-white clay known as kaolin, the main ingredient of Chinese porcelain, is a residual clay and is found in the mountains of North Carolina.

If residual clays stay put, sedimentary clays travel, following the meandering journeys of rain, river, and stream. While the Cherokee and other native peoples used residual kaolin in constructing their wooden buildings and decorating their pottery, North Carolina folk potters have preferred the more “plastic” sedimentary clays so common in the Piedmont. It is this plasticity of clay, its protean capacity to take and keep many different shapes, that makes it such a useful substance.

European pottery traditions in North Carolina reached back to the eighteenth century, when German potters settled in the Moravian communities of Randolph County, such as the town of Salem, which later joined with neighboring Winston. These potters brought with them sophisticated shapes and lively decorations applied with liquid clay (or slip) painted on vessels, which assumed brilliant colors when fired.

Alongside the Moravian potters, a very different tradition began to take shape during the late eighteenth century. In the small farming communities of Guilford, Randolph, and Moore County—the counties of the eastern Piedmont—there was a steady need for containers of all kinds: cups and bowls and whiskey jugs, butter churns, and chamber pots. Farmers with time on their hands could make some extra money by turning and burning, the local words for throwing pots on the wheel and firing them. The raw material, known as mud rather than clay, was particularly rich in the Piedmont. These local farmer-potters performed every aspect of their craft. They dug the clay from the local ponds and river bottoms. They ground it in mills powered by circling mules. They made bricks for their kilns from local clay. And they marketed their pottery themselves, taking it out on the dirt roads by the wagonload to sell to other farmers far away.

The pottery they made was made for use. The forms were dictated by their purpose; the simple glazes, made with cheap materials such as salt and glass, made the vessels watertight; artistic flourishes of any kind were time-consuming, and hence rare. Some of the earliest documented potters in Guilford County were Quakers, whose commitment to plainness and simplicity was part of their creed. The beauty of these early pots consisted of a confident but understated presence. “These guys were consummate artists,” the ceramic historian Charles (“Terry”) Zug III told me, picking up a whiskey jug by the nineteenth-century North Carolina master potter Nicholas Fox. “They couldn’t make a crappy piece.”

By 1900, local potters from a few families had been making pottery for several unbroken generations, and the old forms had survived unchanged: the jug, the pie plate, the pitcher, and the rest. But various forces were bringing this trade to an end. One was the ready availability of mass-produced containers that were both cheap and reliable. Another factor was the steady diaspora of young people moving from the country to the city. Making pots and farming on the side hardly seemed an alluring occupation for a young man with ambitions. Prohibition, and the collapse of the market for whiskey jugs, made a bad situation worse.

It took visionary outsiders like the Busbees, people with money and fresh ideas, to renew North Carolina pottery. Jacques Busbee’s cultural tastes were not unusual for his time. Americans were increasingly anxious about the ravages of industrialism and the loss of intimacy with handicrafts and the land. Such worries had inspired William Morris and John Ruskin, in the wake of the Industrial Revolution, to found the Arts and Crafts movement in England during the nineteenth century. What set Jacques Busbee apart was his drive to make his dream of traditional rural craftsmen a reality.

But renewal also required potters, young people who had both the inherited skills to make the old forms and the flexibility to learn new methods. The Busbees went in search of local potters during a period when, as Zug notes, “pots were viewed as simply another cash crop like tobacco, cotton, or corn.” For the Busbees, however, there was something exalted and poetic about these rural farmer-potters. Juliana liked to tell people that it was an orange pie plate, found at a county fair, that fired her interest in Carolina pottery. “It was that empty pie plate we set sail in,” she wrote, “on an adventurous journey.”

When they stepped down from the train in the hamlet of Seagrove during the wartime winter of 1917, the Busbees regarded the potters of Moore County as the embodiment of great traditions reaching back to the early settling of the countryside. Jacques persuaded himself that there were direct links between these local potters and the Staffordshire potteries of Wedgwood and Spode. “Some of the potters [Jacques] found had come from Staffordshire, England, about 1740,” Juliana Busbee wrote. “One old potter, whose name was Sheffield (pronounced Shuffle) was a mine of information… Imagine the surprise of finding his name to be Josiah Wedgwood Sheffield!”

There is no greater name in the history of pottery in the English-speaking world than Josiah Wedgwood, whose “china” dominated the transatlantic trade during the eighteenth century and after. Juliana’s story was probably something of a wishful fabrication, but it shows how eager the Busbees were to establish a lineage connecting North Carolina potters with earlier traditions in England.

The Busbees tracked down two young potters, Benjamin Owen and Charles Teague, and encouraged them to develop classic Staffordshire-like shapes: pitchers and jugs, plates and saucers, creamers and sugar bowls. Initially, the Busbees and their potters were aiming for something like North Carolina Wedgwood.

Then Jacques Busbee had an epiphany. He had noticed striking similarities in shape and glaze between Asian pottery in the Metropolitan Museum in New York and the North Carolina pots that interested him. Weren’t these simple Southern jugs and bowls, he wondered, a kind of cultural rhyme with the ancient pottery of China and Japan? Busbee began taking photographs of pots at the Metropolitan Museum and showing them to Ben Owen back in North Carolina. Owen would then adapt the shapes to the native clays and glazes. Purists might object; it was a hybrid art that Jacques Busbee was cultivating in the Piedmont. But the alternative to such grafting was death: the end of the road for the North Carolina ceramic tradition.

“An earthy pot should contain solid firm earthy beauty,” Ben Owen remarked. His aesthetic creed was a Quaker plainness:

I avoid showy colors or any display of magnificence. Quietness, modesty of form, and harmony are elements I attempt to achieve… The oriental masters have inspired me a great deal. I appreciate the quiet beauty and simplicity of form which they used to achieve balance and symmetry. The slender flowing lines are graceful, yet with strong powerful proportions, and never cease to amaze me.

Ben Owen’s pots are among the most beautiful ceramic vessels ever made in the United States. White, narrow-mouthed vases that hark back in their understated grace to China and ancient Greece; ample, full-bellied, foot-tall jars in a turquoise glaze with dark purple showing through; pine-green bowls of a simple but unmistakable authority—these pots take one’s breath away.

Among the dark pines and red clay of Jugtown, the Busbees cultivated an atmosphere of rustic simplicity in the log cabin they built for themselves. It was rather elegant for a log cabin, and hardly the kind of house anyone in the neighborhood lived in, but it helped to sell the Jugtown pots. The dominant style in the cabin was Japanese restraint, with rustic touches borrowed from the surrounding countryside.

My mother was invited into the Busbee home on one of her visits to Jugtown as a child. “My most vivid image is the living room,” she remembered. “The sun shone in through the windows and Juliana Busbee had placed a glass vase on a table, so that when the sun shone on it one saw the rainbow. The windows had charming thin orange curtains. I can see them blowing in the breeze.”

5.

I took a decisive step toward the world I had glimpsed at Jugtown—the daily toil in the pottery workshop, the simple and beautiful shapes emerging from the lump of clay, the seasonal rhythms of digging, throwing, and firing—when I accompanied my parents to Japan during the fall of 1970, when I turned sixteen. Everyone in our family seemed to be making a new start that fall. My mother, in love with purple-blue indigo, was taking a break from painting to learn the traditional Japanese techniques for dying fabric. My father, whose interests had shifted from organic chemistry to Asian alchemy, was brooding over ancient Chinese incense burners with complex geometric patterns.

With nothing better to do, my brother Stephen, four years older, and I had followed our parents to Japan with dim plans to study Japanese and, as my father put it, “steep ourselves in Japanese culture.” Japan was the boiling water; we were the tea leaves.

We moved into a Western-style stucco mansion in the town of Nishinomiya, near the sprawling port city of Kobe. Our house was in a stately row of residences built for missionaries on the edge of the campus of a Christian college. All the trees on the campus had been chopped down during the student riots of 1968, in protest against the Vietnam War and the ongoing presence of American troops on Japanese soil.

Ours was a peaceful wooded enclave, with broad lawns on one side and, across our quiet street, a cliff that descended abruptly to the hodgepodge streets of the shabby town of Nigawa, not a hundred yards away and yet entirely invisible from Missionary Row. Our cement street ended in the hills, swallowed up in a stand of impenetrable bamboo and exposed rock. There were clearings in the bamboo where students from the university met in clubs to practice the stern martial arts of karate, kendo, and archery.

One sunny afternoon in late November, two policemen knocked urgently on our door and asked in broken English if we had a television. They mentioned the name Mishima. We watched the footage together. The novelist Yukio Mishima had stormed the Tokyo headquarters of the Japanese Defense Forces and, in a screaming harangue to the soldiers, had demanded a return to the old virtues of a warrior Japan led by the emperor. Brandishing a samurai sword, Mishima cut open his own stomach, in the ritual of seppuku. Then an associate chopped off his head. Like some latter-day John Brown, Mishima had hoped to spark a national movement but succeeded in provoking scorn and disgust instead.

For a few weeks that fall, I attended classes at the local Japanese high school, struggling to keep up with the math homework and helping out in the English class. The boys were reading “Little Red Riding Hood,” an impossible title for them to pronounce. “Food,” they would say. “Hood,” I would patiently repeat.

Two houses down from ours, an American professor, recently divorced, lived with his infant son. He was, I think, a historian of some kind, and he had, it turned out, two keys to open doors for me. The first was his house, or rather, for us, a single room, where my brother and I spent many nighttime hours. Officially, we were babysitting, though the child was always asleep when we arrived and slept through the records we played at full volume in the book-filled living room.

That room comes back to me now as particular sounds and particular books. We were starved for music in Japan, where American music was rarely played on the radio. In the historian’s house, we listened over and over again to Judy Collins’s album Who Knows Where the Time Goes. On the shelves next to the record player were slim volumes of poetry from Grove Press and New Directions, by Gary Snyder and Allen Ginsberg, and piles of old magazines, Ramparts and Evergreen. I read Kerouac’s The Subterraneans that fall, and it captured some of my own aching sense of loneliness and restlessness.

I remember reading a book of poems by Denise Levertov called The Sorrow Dance, especially a haikulike poem called “A Day Begins,” which contrasted a squirrel found bleeding in the morning grass with a scene nearby of mauve irises opening to the sunlight. With these lines about opening flowers, between life and death, a door opened for me as well. It was my first encounter with Levertov and the Black Mountain poets, who meant a great deal to me later on. It was also the first time that I read poetry in the famished way in which I have read it ever since.

7.

The second door opened for me later that winter. My father must have mentioned my interest in pottery to his colleagues at the Christian college. I had joined the pottery club at the high school and I was making pots on an electric wheel there. The historian, the same one with the records and books, had once taught a young woman in one of his classes who wanted to be a professional potter. She belonged to one of the pottery-making families in the region of Tamba, a mountainous enclave famous for its dark, mottled jars since the twelfth century. Women, long associated with bad luck in rural Japan, were not allowed to throw pots at the wheel. This young woman, however, was training in ceramics at an art school in Kyoto. It was thought that with this special expertise, she might manage to break the male monopoly in her home village of Tachikui, the last of the pottery villages of Tamba.

Inquiries were extended on my behalf, in the ritualized way in which such things are arranged in Japan, so that no one’s feelings are hurt if negotiations lead to nothing.

Might there be a place at the wheel for a gaijin, a foreigner, in love with Japanese pottery? The surprising answer came back that indeed there was.

In the middle of February, I began the zigzag journey of trains and buses to the remote destination of Tachikui. The first change of trains was at Takarazuka, a gaudy town of neon and nightlife known for its all-female theatrical revues. From that momentary explosion of electric light, the train entered a world of shadows, as the dim interior filled with schoolchildren awestruck at the tall foreigner hunched on the wooden banquette. This was before television was widespread in the Japanese countryside, and many of these children had apparently never seen an American in the flesh. They giggled nervously or frowned with a slight but fearful hostility.

The unfamiliar landscape spread out from the tracks. Rectangular rice paddies crisscrossed with frozen irrigation canals extended to abruptly rising hills topped with snow. Red Shinto shrines with little peaked roofs like newspaper hats jutted from the jagged hills like surveillance cameras. Nestled among the shrines were caves clotted with vines: the ruins of the ancient kilns of Tamba.

As I rode in the battered train, tugged uphill by a steam locomotive belching black smoke, I felt as though I was traveling back in time. I got off at a makeshift wooden station reminiscent of the Wild West. The last leg of the journey was in a bus, swerving dangerously around turns in the dirt road, and arriving with a flourish at the wishbone intersection right in the middle of Tachikui.

8.

For hundreds of years, the people of Tachikui have divided their work according to the seasons. During the warm spring and summer months, they farm rice in the paddies spreading toward the mountains. During the fall and winter, they make pottery in the small storehouses, known as kura, adjacent to their living quarters. I was to live and work with the Takeda family, who owned a small pottery along the main street of the village. A few houses farther down the street was the much larger Ichino establishment, where the best-known potter of Tamba produced his wares. Ichino had a big modern building and a staff of assistants. He had decisively entered the twentieth century.

The Takeda establishment, by contrast, harked back to another age, when the family was the basic unit of production, and everyone in the household had a clear job to perform. The iron routine was unvarying, but there was a great deal of joking and fun amid the tedium. The day began at dawn, with a raw egg over hot rice for breakfast and a few pickled white radishes on the side. The other meals were served from a great kettle of brownish soup, which was kept simmering on the stove and to which various vegetables and bits of fish, caught in the local irrigation ditches, were added daily.

The pottery workplace was a tight room with a low ceiling, made even lower by overhead racks for stacking pots. Everything in the room, including the blaring radio and the steaming kettle for making tea, was yellow-gray, the unvarying color of the local clay. There were two electric pottery wheels that revolved, in the Korean fashion, counterclockwise. Two men, father and son, worked at the wheels, turning out pickle jars and teacups at a rapid pace. Two women, the mother and daughter-in-law, sat cross-legged on the floor and made lids for the pickle-jars, using plaster molds. They pushed clay firmly into the molds with their fingers, then cut along the face of the mold with a wire, and lifted the finished lid from the mold with another piece of clay. A small twist of clay, applied to the rounded top as a handle, completed the lid.

I was invited to join the women on the floor, making lids hour after hour through the long morning, with an occasional break for a cup of steaming green tea. Then, in the afternoon, I helped them load the wood-burning kiln, one of the great Tamba noborigama, or climbing kilns, that snaked up the hill like fire-breathing dragons.

Nighttime at Tachikui is what I most remember. The village was unnervingly quiet in the thick darkness, the silence pierced once or twice in the night by a passing train. The tiny room I slept in was extremely cold. I slept on a hard futon. My feet were warmed by bricks removed from the hibachi, and wrapped in the bottom of the coverlet. If I had to get up at night, the walk to the outhouse was a long one: out of the room with its cold tatami floor and down a steep set of stairs, then outdoors along a stone path to the wooden outhouse. It was from this outhouse that buckets of “night soil” were carried out to the rice fields in the predawn hours and dumped there, giving, I sometimes imagined, an acrid taste to the little brown carp that floated in our soup.

9.

At the time that I worked in Tachikui, during the winter of 1970, the local ceramic production was undergoing a renaissance, thanks to the Mingei, or “art of the people,” movement. There was a new demand for Tamba pots and a new understanding of the significance of the Tamba pottery tradition. I recognized the broad aims of Mingei, the recoil from industrial design and the embrace of handmade irregularities, from my visits to Jugtown. In the pickle jars and sake bottles of Tamba, the mark of the hand was as palpable, as touchable, as in Ben Owen’s tobacco-spit pitchers.

The Mingei movement was founded by Soˉetsu Yanagi, an urbane Tokyo aesthete who, around 1916, fell in love with the ancient, rough-hewn pottery of Korea. He wrote an influential book, The Unknown Craftsman, laying out his ideas for aesthetic renewal through traditional handicraft. Yanagi soon joined forces with the formidable English potter Bernard Leach, author of the bible of modern folk pottery, A Potter’s Book. Like the Busbees in North Carolina at exactly the same time, the 1920s, the two men went in search of traditional Japanese potters and pottery techniques as an alternative to modern industrial production.

The Mingei movement stalled during World War II and its difficult aftermath in occupied Japan, when the ravaged country placed its hopes in the revival of Japanese industry, especially the high-tech world of electronics. As in the United States and elsewhere, the sixties proved something of a watershed, with a collective revulsion in response to the nuclear age and its military-industrial complex. With renewed interest in traditional Japanese arts, Tamba, with its long tradition reaching back to imported Korean potters during the sixteenth century, was at the forefront of the revival. Leach’s American wife, Janet, whom he had met many years earlier at Black Mountain College in North Carolina, apprenticed herself to Ichino at Tamba. In 1970, the year I arrived there, the distinguished American potter Daniel Rhodes, who also had close ties to Black Mountain, wrote a beautiful book called Tamba Pottery: The Timeless Art of a Japanese Village.

As a direct result of all this reawakened interest in traditional pottery, the Tachikui potters worked together to establish the Tamba Museum, where visitors could experience directly the extraordinary ancient pots of the region. Rhodes wrote movingly of what they found there:

The pottery of Tamba is not a very large part of Japanese ceramics as a whole. In fact, many accounts of Japanese pottery barely mention it. It is not one of the more glamorous kinds of pottery, and few examples of it are to be seen in collections or in museums outside of Japan. Nevertheless, it is one of those expressions in clay which is peculiarly Japanese and one which has had an unusually long history. It was little influenced by and had little influence on other types of pottery. Tamba grew directly out of the social fabric; it was the product of farmers who were close to the basic essentials of existence. It had, therefore, a directness, an honesty, a suitability to purpose and lack of self-consciousness, which have been the mark of the best pottery everywhere.

When I visited the Tamba Pottery Museum, I fell in love with a magnificent storage jar from the Kamakura Period, around the thirteenth century. It was a foot and a half tall but it had the authority, the rootedness, of a much larger pot. With its ruined lip and its dark scars from the kiln, it had the weathered look of a survivor. The bare clay was the dark purplish red of Tamba, with a great swath of white-and-green natural ash glaze dripping down the side, like a sash thrown cavalierly over the pot’s shoulder.

As I sat on the floor with the women of the Takeda family, making the lids of modest pickle jars, or joined them in loading the kiln on the hillside, I was for a few weeks a part of a centuries-old tradition.

That winter in Tamba remained an island in my past, one of those events in one’s teenage years that retain a magnetic pull, even as life moves on in other directions. Then, on a recent trip south to visit my parents, it opened up for me again when I pulled into Johnny Burke Road in the red-clay hamlet of Pittsboro, a half hour south of Chapel Hill, and encountered Mark Hewitt’s big pots basking in the sun.

These monumental pots—glazed in the rich oranges and juicy alkaline browns of traditional Southern folk pottery and studded with bits of partially melted blue glass—were of truly Ali Baba–esque proportions. It was a brisk spring day, and the way the planters and storage jars gathered the dark pines and the cloudless blue sky around them reminded me of Wallace Stevens’s poem about the jar on the hill in Tennessee, which makes the “slovenly wilderness” surround it.

Hewitt is one of the best known ceramic artists now at work in America. Friends in New England with a serious interest in pottery had mentioned his work to me over the years; when I started thinking about Jugtown and its place in my life, they urged me to visit his workplace. Hewitt’s low-lying house lies at the end of a gravel road, with a fenced pasture sloping up the hillside opposite the house. A tenant next door keeps ducks and chickens; occasionally a rooster complains in the henhouse. Down from the main house are two huge yellow-brick mounds, like whales surfacing; these are Hewitt’s kilns. Alongside one of the kilns, on the day I arrived, was a row of a half-dozen pots, big enough for a man to curl up inside. As I walked down toward the kilns, shadows infiltrated the late afternoon and lingered in the boughs of the tall pines.

Hewitt, a tall and athletic Englishman of craggy good looks,

came striding out of the pottery shed to greet me. Clay was on his overalls and clay was in his bones. Although his “big-assed pots,” as he jokingly calls them, have entered many museum collections, Hewitt prefers to call himself a “functional” potter, a maker of pots for use, as opposed to the “studio” or art potters whose work is intended for display. Even his outsize pots are targeted for specific purposes; he’s more gratified to see a tree growing in one of his planters than to see the vessel standing empty in someone’s living room. The sheer size of Hewitt’s pots draws on nineteenth-century North Carolina pottery practices, when potters made large-scale whiskey jugs and grave markers; it was only later that Jugtown and other folk potteries found that smaller pots appealed to urban buyers and collectors.

Hewitt, born in the English industrial city of Stoke-on-Trent in 1955, has his reasons for being touchy regarding the traditions he works in. Both his father and his grandfather were directors of Spode, the manufacturers of fine china. Hewitt could easily have entered the family business (both Spode and Wedgwood, its main competitor, have since hit hard times), but having grown up in the counterculture of the early 1970s, he was drawn instead to the anti-industrial craft practices inspired by Ruskin and William Morris. He liked to look at the pottery in the Bristol Museum, where he was taking classes at the university. He liked the rough-hewn Asian pots and the handmade English pots.

Then someone gave him Bernard Leach’s A Potter’s Book, with its heady combination of clear directives for how to throw, glaze, and fire a pot, and its insistence on the superiority of the clean lines and austere decoration of classic Asian pottery, and he knew where he was going. Hewitt served a three-year apprenticeship with Michael Cardew, another legendary ceramicist and the author of Pioneer Pottery, who had been Leach’s first pupil. Cardew had worked in West Africa—in Ghana and Nigeria—grafting indigenous practices onto Leach’s distinctive aesthetic blend of English slipware (pottery decorated with colorful liquid clay before firing) and Japanese simplicity.

During the time when Hewitt was working for him, Cardew happened to have a Jugtown pot in a place of honor in his living room. The Jugtown potter Vernon Owens had visited Cardew and left the little salt-glazed jug, decorated with a blue-and-brown flower painted on the side. Cardew “was famous for condemning other people’s pots and he would often break them,” Hewitt says. “But this little jug ended up on the big Welsh dresser that was at the center of his house in the dining room among all of his most treasured pots. It had a legitimate presence, it had passed Michael’s test.”

Wishing to strike out on his own, Hewitt, accompanied by his American wife, Carol, came to Pittsboro in 1983, attracted by the rich ceramic traditions and by the abundant local clay. “I was fascinated and charmed by it all,” Hewitt says of the varied North Carolina pottery scene. “The potters were all different from each other, each with incredible skills and talents, using local materials.” Such regional pottery traditions are rare, Hewitt says. “They are like wildflowers that only grow in certain special soils and microclimates.”

On my way down to Hewitt’s, I had spoken with Terry Zug, at his place in Chapel Hill, about the blessings of working within a tradition. Zug mentioned how difficult it is for a young potter, faced with the bewildering array of national and aesthetic possibilities (from the no-frills Japanese ash glaze of Bizen—a favorite of American potters—to the playful postmodern allusiveness of Judy Chicago), to forge an individual style, or personal cohesion, as Zug called it. Working in the mode of a particular region, like the North Carolina Piedmont, narrows the number of forking paths for a versatile potter like Hewitt.

11.

I woke up early the next morning to join Hewitt for the morning’s work. Duck eggs from the tenants next door made a sturdy breakfast. Pink sheaths of cloud wreathed the pines on the horizon, where the sun was rising like another giant egg. We entered the wooden door of Hewitt’s workplace—“It’s not a studio,” he said; “studios have chairs”—a converted chicken house with a mottled dirt floor and a potbellied black woodstove in the center. A bucket of water on the stove steamed in the morning chill, with Miles Davis’s Kind of Blue on the CD player.

It reminded me of the Tamba workspace, with its simmering teakettle. Shelves in the back were lined with drying plates, mugs, and the slim tumblers that Hewitt makes for what he calls the iced tea ceremony, an informal Southern version of the Japanese ritual. Hewitt showed me some glazes he had been experimenting with: a marbleized effect (garbleizing, he calls it) he gets from dripping liquid red clay into pools of white. He was excited about some progress he had made in reproducing the famous “hare’s fur” glazes of China, much admired by tea ceremony connoisseurs in Japan.

That day, Hewitt was making identical half-gallon jugs from three-and-one-half-pound lumps of clay. He stood at one of the electric wheels, one leg thrust back for leverage, and worked fast. “It takes a long time to learn the music,” he said, “to make small things very well.” The apprentices arrived at eight thirty, and Hewitt gave them their marching orders. I’d already heard about one of them, Alex Matisse, from friends back in Greensboro. A great grandson of the French painter, Matisse had lasted a year at Guilford College before dropping out to pursue a career in pottery. He started feeding clay into the pug mill, a six-foot dragon of a machine that homogenizes the clay and eliminates the pockets of air that can ruin a pot.

12.

Hewitt and I had been talking about the allure of native clays and the special pleasures of making pots from them. I happened to mention that my mother was from Cameron. Hewitt looked astonished. Cameron clay, he remarked, was the basis of his current work. He went even further. Cameron clay was his salvation. He led me to the entry area of the shed, where expanses of local clay were laid out in various stages of preparation. He handed me a chunk of pale gray clay with a yellow tinge. “That’s the Cameron clay,” he said.

A few years back, Hewitt explained, he had been having trouble firing his big pots. “You know those moments when terror sends an impulse that grabs your testicles?” he asked. “Well, for a couple of firings, at six in the morning, with the sickening pop muted by flame and smoke, I’d hear the pots opening up, as if a butcher was performing open-heart surgery on them using a meat cleaver.” Clearly, he needed to find a new clay, and quickly. His previous supplier, a brick company, mentioned that they had found a promising seam of clay in a sand pit among the spindly pines and scrub oaks in the sand hills outside of Cameron, thirty miles from Hewitt’s pottery.

Hewitt evoked the ecstasy he experienced in coming across the good clay he needed for his livelihood: “like stories of native peoples crawling on their knees the last few yards to sacred outcrops of hematite, or white clay, with which they adorn themselves.” Driving to Cameron in his pickup truck, he was “singing a song, jumping in my seat, anxious to see this clay, get a sample, take it home, have it analyzed, make some pots, and find out whether it would be a good foundation for my clay body.”

The scene at the sand pit, with its clutter of prefab offices and the roar of front-loaders and circling dump trucks, was like something out of Mad Max. There, in the bottom of the pit, was what Hewitt had come in search of.

A seam of clay, about twelve feet thick, was clearly visible beneath the upper layers of sand and gravel. The slightly moist clay was pink from a token stain of iron, breaking into irregularly shaped nuggets about the size of baseballs. I was in paradise. I dug my shovel in. Clay cleaves with a certain thunk; it’s not got the siftyness of sand or the harshness of gravel. Too sticky and it’ll stick to the shovel, like shoveling molasses; too hard and the point of the shovel will bounce back at you.

Mark Hewitt

The clay far exceeded Hewitt’s expectations. “You could say that I’ve built my career on Cameron clay,” he told me. “It’s a tough and reliable clay that’s as safe as houses.”

After leaving Hewitt’s pottery, I drove down to Cameron to see for myself. I’d forgotten how the houses on the main street, many of them antique shops now, have sand rather than grass out front. The locals sweep their yards rather than mow them. I pulled into the sand pit as a huge truck was exiting. I’d come unannounced and blundered into one of the trailers. A man in a ponytail was testing sand samples for highway standards. “Better see the boss,” he said, when I told him I was interested in clay. The boss turned out to be a friendly young Englishwoman named Karen McPherson, whose office was covered with photographs of dressage horses—an immediate bond, because my wife, Mickey, is also a serious rider. She offered to drive me down, through a mile or so of wasteland, great canyons of sand, to the clay pits Hewitt had described. “These must be the sand hills,” I said. “That’s right,” she said. “We’re getting rid of one of them.”

13.

I must have chosen the hottest week of the summer to return to Pittsboro, a year or so after my first visit, to watch Mark Hewitt fire his big groundhog kiln. It was 98 in the shade when I pulled into Johnny Burke Road. Hewitt and his two apprentices were carrying the final load of pots from the workshop to the forty-foot kiln, which looked like a beached whale in the merciless summer sun. No one packs a kiln more tightly than Hewitt; multiple shelves of vases, mugs, tumblers, plates, and bowls—roughly two thousand in all—were wedged in around the huge pots that are part of every Hewitt firing.

Accident enters the potter’s domain through many doors, but none is more dramatic than the wager of the kiln. So many things can go wrong in the swirling flames of a cross-fired, wood-burning kiln. “If the fire sinks, or grows too hot,” wrote the French poet Paul Valéry, “its moodiness is disastrous and the game is lost.” Hewitt has come to treasure the gifts of chance. Where pots touch accidentally, discolored “kisses” may form. Where bricks on the ceiling of the kiln melt in the firing, “potter’s tears” may drip onto the shoulders of the pots huddled below. Quartz pebbles will blow out from the clay during firing, resulting in what North Carolina potters call “pearls.” Bits of grass or twigs will flash out of the surface of the fired clay, leaving blemishes or beauty spots.

“While the fire is in action,” Valéry said, “the artisan himself is aflame, watching and burning.” Watching Hewitt during the side-stoking of the kiln, as he nervously eyed the temperature gauge and carefully slid another slat of wood into the flames, was like watching a ship captain responding to shifting winds. It was a more delicate operation than I’d imagined, not at all like heaving coal into a steam engine.

As he got ready to spray some salt into the chambers of the kiln, in hopes of getting the pebbly effect in the glaze that North Carolina potters have achieved for two hundred years, Hewitt shrugged, wiped the sweat from his brow, and said, “At this point, all you can do is pray.” It seemed appropriate, for the anxious but hopeful mood of the firing, that the biggest pot in the kiln, a “sentinel” based on nineteenth-century North Carolina grave-markers, was inscribed with the Nunc Dimittis, the traditional evening prayer of the Anglican service: “Lord, now lettest thou thy servant depart in peace.”

14.

The traditions of British and American folk pottery have come full circle in Hewitt’s work. I had often thought of Bernard Leach and Jacques Busbee as strangely parallel figures in the history of folk pottery. Both had sought to resurrect vanishing pottery traditions, one in England and the other in North Carolina. Both had looked to the spare shapes of Song China and early Staffordshire for models. And both had founded potteries to reflect their ideas, staffing them with gifted potters like Shoˉji Hamada and Michael Cardew and Ben Owen. And now, here was Hewitt, trained in the Leach tradition and well versed in Japanese methods, but working with the clays and glazes and techniques of Busbee’s Jugtown, making pots that would outlast us all.

Mist was lifting from the fields early the next morning, and the great kilns lay sleeping. But Mark Hewitt was already down in the pottery shed. As I watched him trimming some dinner plates—placing them upside down on the wheel, centering them, and cutting away the yellow-gray clay to leave a clean, articulated base—I could have been back in Tamba, back in the daily, age-old rhythms of clay.

15.

A few months after my visit with Hewitt, my aunt Juanita, Uncle Alec’s widow, sent me a pitcher that Ben Owen had made, the same pitcher that had sat for so many years on the table in the hallway in my grandparents’ house in Cameron. It seemed to have ripened, like a burnished pumpkin in the fall, since I had last seen it so many years ago. There were mossy green shadows on its orange belly, like the bamboo grove in twilight.

I thought of the worlds its homely shape had opened for me. It had brought back memories of Jugtown, with its simple rhythms of turning and burning, and my grandparents’ life of tobacco and red brick. It had taken me to a remote village in Japan. And the same rustic pitcher, with its incised lines around its strong shoulder, had taken me to Mark Hewitt’s place in Pittsboro, where new shapes and surfaces were drawn from English, Japanese, North Carolinian, and African pottery traditions.

I thought of something Hewitt had written:

Much is demanded of pitchers. They are among the most knocked about and banged-up pots, being pulled out of larders and refrigerators, dipped in wells, put under faucets, lifted laden and heavy, poured from, dribbled, spilt, and cursed; they are vulnerable to mishandling. Pitchers are exacting to make and tougher to make survive.

This pitcher, I realized, was a survivor. I thought of the turning wheel and the turning world, the magic, alchemical transformations of the kiln. And I thought of Ben Owen making handles, thousands and thousands of handles, each handle firmly and gracefully connecting the world of art to the world of use.