1.

As a child, I was a passionate collector of postage stamps from Germany, especially those of the Third Reich—red, black, and white—which I carefully mounted, with little adhesive hinges that I licked to stay in place, in my heavy black stamp album. Among my treasures were several big red stamps of the führer, surrounded by swastikas, saluting the fatherland. These stamps exerted a special attraction for me beyond, I like to think, a child’s predictable fascination with forbidden things. My father, in any case, made no attempt to prevent me from collecting these stamps, nor do I remember him expressing any particular feelings about them. These lurid stamps promised, in some obscure way I could only dimly discern, to put me in touch with a buried period of my father’s life.

The shadow over my father’s childhood was more easily defined than my mother’s catastrophic loss of Sergei Thomas, but it was also, somehow, more elusive for me. One could say “Hitler” or “the Holocaust” or “World War II” and feel that one had somehow named the shadow, given it a label, like the carefully penciled captions in my stamp album. And yet none of those words, with their ominous and melodramatic historical weight, named him, the particular man with the slight build, the fly away hair, and the unplaceable accent (echoes of Berlin and London overlaid with Indiana and North Carolina) who was my father. He had always seemed to me not just different from the other fathers I knew growing up in the Midwest but somehow radically foreign, as though he had come from some imaginary realm.

At times, my father must have felt like such an alien himself. By the age of twenty-one, when he came to the United States, he had done a great deal of traveling, if travel is the right word for the wrenching displacements that external circumstances periodically forced upon him. Crossing the Atlantic Ocean for the first time in 1946, he had written of his own disorientation and momentary panic:

Whatever was I doing here on this ship, halfway across the Atlantic, having cut myself off from one world and not yet started on another? A weird ghostlike existence I’ve never experienced before.

As an organic chemist by profession, trained in a hurry in wartime London, my father had a special interest in chemical bonds, those connective affinities, or valences, that are the basis of chemical combination. He loved to tell my two older brothers and me, when we were children, about Kekule’s dream, in which the great German organic chemist suddenly envisioned the hexagonal structure of benzene, with its alternating single and double chemical bonds, as a snake grasping its own tail in its mouth.

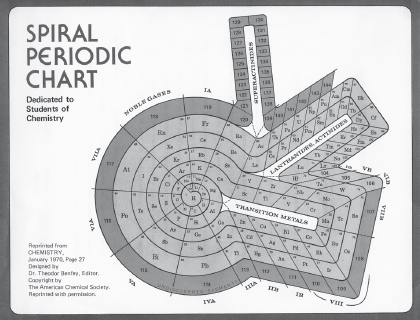

My father’s well-known spiral or “snail” design of the periodic table of the elements, which he first conceived in 1964 for Chemistry magazine, seemed to symbolize his creative and intuitive approach to the sciences. He felt unhappy with what he called the “mammoth gaps” in the first and second periods—or rows—of the traditional periodic table. Such a haphazard deployment

of elements neither lent itself to teaching, nor did it seem to him an adequate reflection of the relationships among the different elements. Always drawn to geometry and the arithmetic patterns often found in nature, he was convinced that a more elegant arrangement might be found for the elements and their periodicity—their cousinship with other elements arrayed above and below them. The result was his famous snail.

My father’s interest in geometry resurfaced a few years later, during the year we spent in Japan in 1970. Designs on the surface of a bronze incense burner from the Tang era, in the imperial collection in Nara, persuaded my father that the ancient Chinese knew—contrary to the assertions of Western historians of science—the fundamentals of Euclidean geometry and specifically were familiar with the dodecahedron (twelve identical pentagonal faces) and other regular solids in which certain molecules array themselves. He traced the dodecahedron pattern, as he found it on the incense burner in Nara, to Persian pottery of the Sassanian period, decorated with “a symmetrical enclosed three-petal flower pattern.” He noted that “a number of Persians including skilled craftsmen came to China after the overthrow of the Sassanian empire by Islam in the seventh century.”

But my father suspected that the Chinese were aware of the dodecahedron long before the Persian potters arrived. He discovered that the dodecahedron was also widely used in basketry and reflected that it would be odd for basket weavers making flat patterns with six strands not to stumble upon the form. “May one assume that some primitive man or woman, tired of always weaving six strands to create a hole, chose to weave only five, or even did so by mistake?” he wrote. “That person would very quickly have discovered that one cannot create a flat surface or tessellation with pentagons, that joined pentagons produce closed cage structures.” These cage structures would be dodecahedrons.

During his tenure as editor of Chemistry magazine, my father vigorously defended his occasionally adventurous claims against seemingly more hardheaded objections. I remember a debate he had with the science fiction writer Isaac Asimov, who took offense at my father’s suggestion that some assumptions of astrology seemed reasonable enough, because babies born during the winter were treated quite differently, bundled up against the cold, than babies born in the carefree, clothing-free summer. Asimov was convinced that modern science could not afford to yield an inch to such New Age lunacies. But my father always tried to find out what emotional needs were driving these antiscientific views. He wanted to bring dialogue, mutual understanding—“valence”—to people who disagreed.

My father’s multivalent approach to things was connected, in ways that I have only recently begun to understand, with his interrupted childhood in an upper-class family in Berlin. As I have learned more about my assimilated German Jewish forebears and their abrupt plunge into homelessness and statelessness, my father’s eccentricities increasingly have come to seem like family traits, tendencies that I recognize, for better or worse, in me as well. I have come to feel that over the generations, our extended family has come to live with an underlying conviction about the precariousness of all merely human arrangements. Our suitcases are packed, whether we are lucky enough to be allowed to take them with us.

Two journeys promised to bring me closer to this scene of origins; on both I often felt as though I were threading my way through a disorienting maze of streets and emotions.

The first journey was an actual pilgrimage to my father’s lost childhood city of Berlin, a voyage undertaken with my father and my two young sons.

The other was a journey via the library, along with various stray documents tracked down in archives and private collections. This second journey was in search of my father’s namesake, the famous Sanskrit scholar Theodor Benfey, decipherer of arcane languages and the mysteries of fairy tales, who had long seemed to me an especially striking exemplar of our family traits and tendencies. This enigmatic ancestor had also decoded our shared last name, Benfey, tracing an exotic journey of family origins, exile, and restless wandering.

2.

“Just before my eleventh birthday my life changed completely.” My father wrote those words to my son Tommy, who had just turned eleven, in a letter explaining how his privileged upbringing in Berlin had come to an abrupt halt in 1936. That was the year my father left Germany, for his own safety, to live with foster parents in England. He was separated from his family for what stretched into a decade before he embarked on a new life in the United States. I had often wondered, as I grew up and then had children of my own, what these experiences had been like for my father, what balance of adventure and trauma had marked his early years. Though I knew the basic outlines of his life, I’d never had access to the texture, terrain, and emotional tone of his childhood.

The idea of getting together those two eleven-year-olds, my father and my son, prompted our trip to Berlin during the summer of 2000. That Tommy was born in 1989, the year the Berlin Wall came down, added another magic number to our journey. I wanted to see how much of my father’s childhood in Berlin we could recover, to find ways for all of us to share it. I innocently assumed that it would mainly be a matter of finding addresses, old buildings, rooms.

In retrospect, I realize that there was a darker purpose to these arrangements as well. I wanted to set an emotional trap for my father, to try to rouse in him some response to what I perceived to be the trauma of his childhood, a trauma that, I felt, he had never fully acknowledged with us. Surely, I thought, to be banished from one’s familiar world and adopted into another family in an unfamiliar country, with a decade-long separation from mother and father, must have been devastating. As it turned out, I was the one who stepped into the trap that I had so carefully devised.

During the months before our departure, my father, living in the Friends Homes retirement community in Greensboro, North Carolina, sent a series of letters about his childhood to Tommy, who was studying immigration in his fifth-grade class in western Massachusetts. Ted explained how he had been forced to leave Berlin and his family behind because of his Jewish background. Ted’s father, Eduard, had served in the Kaiser’s cavalry during World War I; my grandmother had proudly shown me the Iron Cross, First Class, that he was awarded.

Trained as a lawyer, my grandfather eventually became a supreme court justice in Berlin, rising to the rank of chief justice of the supreme court for financial matters. Like other attorneys of Jewish background, he had converted to Lutheranism as a young man, both for patriotic reasons—to feel more German—and to advance his judicial career.

My father’s mother, Lotte, belonged to the prominent Ullstein family. Her five flamboyant uncles—Hans, Louis, Franz, Rudolf, and Hermann—ran the House of Ullstein, the biggest and wealthiest publishing empire in all of Europe. The Ullstein firm printed the leading newspapers in Germany as well as bestselling books, with the trademark owl logo, such as All Quiet on the Western Front. The social prominence of the Ullstein family was clear to the philosopher Walter Benjamin, who played with my grandmother’s cousins as a child in the fashionable western neighborhood of Charlottenburg. Benjamin wrote of the children of his acquaintance: “And that it was high on the social scale I can infer from the names of the two girls from the little circle that remain in my memory: Ilse Ullstein and Luise von Landau.”

The Ullsteins had been baptized as a family in the late nineteenth century. But to Hitler, who seized their publishing firm after his rise to power in 1933, they were all Jews. He had a special interest in controlling propaganda, and the “Jewish press” was one of his principal targets. The Nazis fired my grandfather from his supreme court post in 1935, when he was sixty. Ted described how his father had come home ashen faced “because at some Nazi office, when he introduced himself as Senatspräsident Benfey, an official replied, ‘Sie sind nicht Senatspräsident Benfey. Sie sind Jude Benfey.’” (“You are not Chief Justice Benfey. You are Jew Benfey.”)

Assimilated Jews like the Ullsteins and the Benfeys, perfectly at home in the sophisticated and easygoing world of Berlin during the 1920s, slowly came to realize that, despite their social prominence, their money, and their service to their country, there was no future for them in Germany.

The Mendl family, close friends of the Benfeys and also of Jewish descent, fled Berlin for England in early 1936, settling in the town of Watford, outside London. Uncle Gerald was an engineer; his wife, Auntie Babs, was a practical woman with spiritual leanings. They had a son my father’s age, named Wolfgang, and suggested that Ted join them. So my father said good-bye to his family. He saw them briefly—his parents, his older sister, Renate, and his younger brother, Rudolf—on summer visits to Berlin.

The big event of the summer of 1936 was the Olympic Games in Berlin, where Hitler planned to put German greatness on display to the world. My father wrote to Tommy about the excitement of that summer, when his family lived only a mile or two away from the construction site of Albert Speer’s monumental Olympic Stadium.

Every day during the Games, Hitler would drive from his headquarters to the Stadium along a road just a few minutes from the Fürstenplatz where we lived. We all went to the nearby Heerstrasse (Army Street) and waited for Hitler and his motorcade. And when he appeared in an open convertible, we all cheered like mad and everyone shouted “Heil Hitler!”

My father and his siblings knew nothing about Hitler’s hatred of the Jews and his threats against them. Their parents, as my father explained, knew but didn’t want to scare them.

Shortly before the Olympics began in Berlin, the German heavyweight boxing champion, Max Schmeling, had defeated Joe Louis to become world champion. Schmeling’s victory over his African American opponent was hailed in Germany as a sign of the superiority of the Germanic peoples. Two years later, as my father reported to Tommy, he again returned home for summer vacation.

As usual I traveled in one of the big trans-Atlantic liners, it must have been either the Europa or the Hamburg. It had come from New York and was stopping in Southampton in the South of England to disembark passengers for Britain and pick up passengers for Germany. I was traveling third class—my family no longer had much money—but once or twice a friend and I sneaked into the first class area. One of these times we walked past a fancy lounge and in the back of it sat Schmeling. He was coming home after being defeated in the first round in a rematch with Joe Louis.

By 1938, the time for half measures and hope was over, and my father’s family prepared to leave Germany. His brother and sister joined him in England later that year. Their parents followed during the spring of 1939, and in September the war began. After a brief reunion in England, my father’s parents and his siblings left for the United States in January 1940—without Ted.

These arrangements had always seemed puzzling to me. I had heard explanations. Ted, it was said, was comfortable with the Mendl family. He and Wolf were close friends, essentially brothers. He was doing well in school. He was on an accelerated track to earn his PhD in chemistry in 1946, when he was barely twenty. His parents would get settled in the United States, and he could join them afterward. As the war dragged on and the German submarines made Atlantic crossings impossible, “afterward” must have seemed forever, and Ted didn’t see his family again until the end of 1946, when his childhood was long over.

4.

My German grandparents lost everything in the war, except the bits of jewelry that my grandmother smuggled into Ted’s suitcase when he returned to London from vacations. But of course, they were among the lucky ones. Recognizing the danger, my grandmother had applied for an American visa. Her sister, the well-known weaver Anni Albers, was already in the United States, based at Black Mountain College in North Carolina, and could vouch for my grandparents’ financial support. Other members of our family were caught in the roundup of Jews after Kristallnacht, when Nazis smashed windows of Jewish shops and beat up Jews in the streets.

My grandfather’s brother Arnold, a doctor, was incarcerated in Buchenwald, the Nazi concentration camp near Weimar. He would probably have died there if his wife, who was not Jewish, had not taken matters into her own hands. The daughter of a prominent German general, she visited the commandant of the concentration camp and demanded her husband’s release. Miraculously, it was granted. My father saw Arnold in England soon afterward, and his hair was completely shaved off. Eduard’s other brother, the banker Ernst, was sent to the camp of Theresienstadt late in the war and survived as well.

My grandfather Eduard got out of Germany just in time, but he didn’t survive the journey emotionally. He was an elderly man with broken English, and he found the delivery jobs he performed in the States humiliating for a former judge. The quick adaptations of his much younger wife probably made things even harder for him. He hunched by the window in their apartment in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and listened to the war news. He was profoundly depressed, as anyone could tell.

When I first knew her, my grandmother, “very tall, thin as a stick,” as a coworker described her, was working as the personnel manager at the Window Shop in Cambridge, a stylish restaurant and bakery on Brattle Street, around the corner from her own home on Mount Auburn Street. At the Window Shop, refugees from Germany and Austria found safe harbor, both as waitresses and as customers, while Harvard professors came to dine on Austrian delicacies. My grandfather, the former judge, was given the task of copying menus.

For me, as a young child visiting my grandmother, it was a special treat to be invited into the kitchen of the Window Shop, where I was given tastes scraped from the baking pans of all the special cakes—the Linzer torte with its diagonal grid of crust across the top and the Black Forest cake. Her good friend Alice Broch, sister-in-law of the novelist Hermann Broch, presided over the restaurant and pampered me. Even today, when I taste the mingled ground walnuts and raspberry jam of the Linzer torte, I am transported back to the cramped kitchen of the Window Shop, filled with the odors of baking cakes and cinnamon. It was my first real window into the sufferings and displacements of the war years.

5.

My grandparents had been living in Cambridge for several years when my father finally arrived there, after the war was over. My father kept a diary of his journey to America, ten pages of single-spaced observations and experiences. I have read these pages again and again, looking for clues to my father’s emotions at the time.

In the first wave of civilian voyages, after the troopships had gone home, passengers were still herded like military personnel into tightly packed bunk beds. Into one of these my father squeezed himself, along with his cello, on December 19, 1946. The cello, given to him by his uncle Arnold, was his traveling companion, as though he were some wandering musician.

After lunch on the first day on board, he suddenly felt feverish and weak. “Went to bed wondering why I should be ill now,” he wrote. “Decided it was relaxation after all the excitement and worry.” Then came a clue to his state of mind: “Thought this might prove to Wolf that I wasn’t quite as cold and unfeeling as I seemed the last days.”

My father was attentive to the young women on the ship, especially the European brides of American soldiers:

There are about 250 on board and they are treated the worst of all passengers. The U.S. officials and nurses treat them as dirt and have no consideration for them at all. They are nine or more in a cabin, each with baby. Babies have no cots, they have to sleep in “hammocks” just like parents. One of them, I was told, fell out at night and by miracle did not hurt itself. They must do all their washing in one miserable little washroom… They were told by everyone before leaving that they would be treated magnificently all through the trip. For how many of them will this be only the beginning of their disillusionment.

My father contrasted his own good fortune with the uncertain future of the GI brides and the other unlucky emigrants he encountered on the ship. “All my life has been like this,” he wrote. “Will anyone ever believe in ten years time when I tell them I got my Ph.D. the day before leaving for America?” He sat on deck and read Goethe’s Faust and looked forward to his reunion with his family.

6.

An eminent psychoanalyst once told my father that all his interpersonal problems could be traced back to a single source: He was separated too early from his parents. Abandoned like Hansel and Gretel in the forest of life, he was trying, against all odds, to find his way back home. It is a sign of my father’s strength, it seems to me, that he also traces much of his happiness in life to the same moment of separation. “My survival,” he once said, in an exchange with his foster brother, Wolf Mendl, “the fact that I wasn’t ended rather early in the gas chambers in Auschwitz, was purely due to the love and care and concern of my family in finding the best way of getting me out of there and Wolf’s family in taking me in.”

In England, my father was a gifted young student. Had he stayed in Germany, Wolf speculated, a Germany without Hitler, my father “would have been a very, very distinguished German professor, but a bit dry.” Even in England, my father knew that this was Wolf’s view of him. It comes across in that vulnerable moment on shipboard when he writes that “this might prove to Wolf that I wasn’t quite as cold and unfeeling as I seemed the last days.” What the apparent coldness masked, of course, was insecurity, and insecurity led in turn to what my father called his drive for excellence:

When you’re in your own family, you feel accepted—you don’t question it—you feel that you belong. I was aware that no matter how much love I was having showered on me by the Mendls to make me feel at home, it was by choice; and so this drive for excelling is part, probably, of the drive for acceptance, and this sense of loneliness, of being apart, came to me probably somewhat earlier than for the average boy and girl.

My father experienced yet another kind of alienation with the bombing of Hiroshima. Although the research he was pursuing in the laboratory at University College, London, was supposedly “pure” chemistry—dispassionate investigations into the properties of certain molecules—he was aware that it also had potential real-world applications, such as explosives and poison gas. And while he knew something about nuclear reactions and the possibility of an atom bomb, the actual deployment of such a weapon was a shock from which he never quite recovered. “I just walked in a daze through London, wondering what I was doing among scientists. I almost dropped science completely and went into something quite different.” Instead, he developed a slight distance from professional science, the intellectual aloofness and questioning attitude that Isaac Asimov had deplored.

He had also moved toward a condemnation of all war. Wolf’s mother had become a Quaker in England. She was appalled at what the Nazis had done to Germany, but she was also disgusted by what the Allies were doing to ordinary Germans during the vengeful carpet bombing of German cities as the war drew to an end. Auntie Babs was deeply drawn to mystical writings and introduced my father to Meister Eckhart and the other masters of the mystical tradition. My father called all this the matrix out of which his own pacifism grew. By the time he left England, he was a Quaker.

Growing up, I had often been puzzled by the idyllic way in which my father described his departure from Germany and his education in England. There seemed a disconnect there. I could see how Wolf was dismayed by my father’s blithe invulnerability, his seeming coldness. I was inclined to agree with the psychoanalyst about the source of my father’s eagerness to please (a tendency I have inherited). My desire to take my father back to Germany had an ulterior motive. I wanted to investigate the scene of the crime. I wanted to see with my own eyes where the separation had occurred, where the child had been abandoned. I wanted to probe the wound.

I had been in Berlin once before, with a student group during the summer of 1977. Berlin was still a divided city then, rife with suspicion, and I remember the sensation of always being watched. Taking the subway under the Wall felt ominous, as though we were entering the underworld—would we be allowed to return? We assumed, a bit grandiosely, that our grim hotel rooms were bugged, our every movement and conversation logged in some police agent’s record. People we met in the East confirmed our paranoia. A Quaker scholar I met in Dresden said that living in East Germany was like living in Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter, surrounded by vigilant Puritans.

This time, by contrast, my father, my two sons, and I waltzed through customs with nary a stamp on our passports or a questioning glance from the smiling officials. We were met at the airport by the German novelist Sten Nadolny, who was writing a historical novel about the Ullstein family, to which my father’s mother belonged. Together we drove into the vast and bewildering urban network of Berlin—dilapidated old neighborhoods, glittering new downtowns, skyscrapers under construction, and bombed-out spaces.

As luck would have it, we arrived on the afternoon of the Love Parade. This annual Mardi Gras–like frolic on the second Sunday in July started in 1989, when a DJ celebrated his birthday by blaring music from a truck as he drove down the Kurfürstendamm, followed by a raucous parade of friends. With no political or religious agenda whatsoever, the Love Parade had become a mob of boozy, scantily clad revelers surging up, across, and down Unter den Linden, the main thoroughfare of the Eastern sector, through the Brandenburg Gate, and into the Tiergarten,

Garden of Exile and Emigration

Berlin’s biggest park. My father and I covered our ears, but the boys liked the relentless techno beat coming from loudspeakers, though the dyed hair and bare breasts took them by surprise. That night, back at the hotel, eight-year-old Nicholas drew pictures of spiked green hair and wrote in his trip diary, “I think they made too much of the word love.”

Our sturdy, unfashionable hotel was within walking distance of the old center (the Mitte, or middle) and the futuristic new skyscrapers of Potsdamer Platz. What I hadn’t bargained for was the hotel’s unnerving proximity to the old Gestapo headquarters, just a block away. The building was destroyed by Allied bombing, but the basement rooms, where prisoners were interrogated and tortured by the SS, came to light during recent construction. The site is now an ongoing archaeological excavation and outdoor museum called Topography of Terror.

On our first full day in Berlin, we visited the architect Daniel Libeskind’s Jewish Museum. Tommy and Nicholas loved the building’s fun-house effects—stairways leading nowhere and narrowing corridors ending in dark shafts. Libeskind’s Garden of Exile and Emigration, a maze of forty-nine concrete pillars topped by willow trees, was the ideal setting for a boisterous game of hide-and-seek. “This place is cool!” Tommy said.

Their irreverence in the labyrinth—a symbol of a tangled world in which so many children did not, in the end, find a way out—made me a little nervous until a museum official put me at ease. One message of the museum is that Jewry survives in its children, she said, and children are especially welcome there. Overhearing these reassuring words, Sten Nadolny remarked wryly, “Exile is terrible for grown-ups, but children can find fun things along the way.”

8.

I was turning over Sten’s observation as we took a taxi to the apartment house in Charlottenburg where my father had lived until the age of eleven. It was a lovely cream-colored stucco building of six stories, built in 1910. We rode up in a cast-iron elevator that rose beside the marble staircase, passing purple-and-pink Secession-style stained-glass panels on each landing. We knocked on the door of Ted’s former apartment. A friendly couple, a lawyer and his gynecologist wife, with their new baby in her arms, invited us in. Ted noticed that the bathroom and its claw-footed tub were unchanged. Ted and Tommy stood in Ted’s old bedroom talking about what it is like to share a room with a little brother.

The apartment seemed warm and comfortable, with the happy family there, but I couldn’t help thinking about how suddenly Ted’s life in it had ended. Looking out the window at the Fürstenplatz below, I remembered a scene that he had once described from his childhood. When word got out that he was leaving Berlin, a long line of classmates had followed him home, shouting “Jude, Jude!” He ran upstairs, but they were still out there, below, screaming. Only one loyal friend stood by him during the ordeal.

If my father felt any sadness, however, he didn’t show it. “I have only pleasant memories of this apartment,” he said, and I realized that I had two cheerful eleven-year-olds on my hands. I was the only one feeling bereft. I had wanted to reclaim, somehow, this vanished German-Jewish world of sophistication and ease, stucco and stained glass, as my heritage, my own personal loss. My father had moved on long ago.

As we left the apartment, Ted was telling Tommy and Nicholas about the “street polo” games that he and his brother had played decades before in the park outside, with bicycles and croquet mallets, during the 1936 Olympics. Ted’s father had taken his children to see the field hockey and polo matches (hence the street polo), and sneaked the kids into the Olympic Pool, even though Jews were forbidden to swim there.

The next day, we visited the Olympic Stadium. Tommy and Nicholas swam in the outdoor pool, and while they toweled off, Ted regaled them with stories of runner Jesse Owens’s triumphs at the Games, and Hitler’s fury that the four-time gold medalist was African American. I stared up at the diving boards, playing over in my mind Leni Riefenstahl’s film Olympia, with its divers gliding through the air. Amid the happy scene of children swimming on a summer day, I again had that aching sense of mourning, though for exactly what, I couldn’t say. Perhaps it had something to do with the sheer richness of Berlin’s history, with beauty and horror so consistently interwoven. But it was also a more personal ache, centered on my feelings about my father.

That sense of unreality was compounded when we stopped at the massive dark-granite court building where my grandfather had presided as chief justice and where the Nazis had later conducted show trials to condemn political prisoners to death. The main door was slightly ajar, so we walked right in. Strewn about was the apparatus of a prewar office building: manual typewriters, ancient black filing cabinets, stenographers’ Dictaphones. It was as though a time machine had transported us back to 1936. Nothing had changed, I thought, nothing at all.

And then, from an office door, a stylish young woman dressed all in black briskly approached to explain that we were standing in the middle of a movie set. They were filming a crime thriller set during the 1930s.

On our last day in Berlin, we made a family pilgrimage to Benfeystrasse, a suburban street named after my father’s great-granduncle, the famous scholar of Sanskrit. Then we spent the rest of the day at the Zoo, one of my father’s childhood haunts. We entered through the chinoiserie Elephant Gate near the shops of the Kurfürstendamm. After visiting the flamingos and panthers, we watched a baby spider monkey learning to jump. He would leap from his mother’s arms and try to grasp a low-hanging branch, miss, fall, return to his mother’s arms, and jump again. It seemed, in the late-afternoon haze, a fitting image of a child’s first perilous steps into the uncertain world.

This handsome city had pushed my father out into the world, and without that expulsion and his ensuing flight to America, my sons and I would never have been born. The baby monkey jumped one last time, grasped the branch firmly, and swung back and forth. I could have sworn that he smiled in triumph.

On my father’s writing desk, there is an egg-shaped silver snuffbox filled with paperclips. A gift from his father, the Berlin judge who liked to recite the opening lines of the Iliad in Greek, it depicts the sun god Apollo in his horse-drawn chariot, summoning the dawn from the eastern horizon. You wouldn’t expect a Jewish family in Berlin to have a special reverence for a pagan god. And yet, for several generations, the Benfey family has traced its origins to Apollo. Even when I was quite young, in my early teens, I remember hearing from my father the notion that our name was a contraction of Ben Feibisch, meaning “son of Feibisch.” The Yiddish name “Feibisch,” I was told, was derived from Phoebus, namely Phoebus Apollo, the Greek god of the sun. So our name, of probable Sephardic origin, meant “son of the sun.”

A grandiose ancestry like this is probably best left uninvestigated. But I come from a family of philologists, lovers of words. And I suspected that the best-known philologist in our family, the nineteenth-century Sanskrit scholar Theodor Benfey, was somehow mixed up in this Apollo business. My father’s namesake, Theodor taught oriental languages and literature in the Hanoverian university at Göttingen. Known for its religious tolerance, its close ties to the British crown, and its scholarly excellence in the sciences and foreign languages, Göttingen attracted many students from Great Britain—including the English Romantic poets Wordsworth and Coleridge—as well as assimilated German Jews like Heinrich Heine and Benfey. “The town itself is beautiful,” Heine wrote after being expelled from the university for dueling, “and looks its best when you turn your back on it.”

Benfey was born in 1809, an exact contemporary of Darwin and Felix Mendelssohn. Though hardly as well known as those illustrious figures, Benfey had his own considerable fame in the scholarly community. At Göttingen, he was a key figure in a circle of prominent language researchers that included the brothers Grimm as well as Benfey’s own teacher, Franz Bopp, the founder of comparative linguistics and the great theorist of the Indo-European origins of modern European languages. It was at Göttingen that the modern conception of languages, as belonging to families with traceable evolutions rather than, say, divine origins, crystallized.

Benfey’s own linguistic skills were legendary. He had learned Hebrew as a child from his father, a Jewish merchant from a town near Göttingen. He mastered Sanskrit on a bet with a friend that he could learn the language well enough in a few weeks to review a book about it. He learned Russian in order to translate an important work on Buddhism. He published the standard dictionary of the Sanskrit language as well as an important edition of the Panchatantra, a collection of Indian folktales. He also prepared a scholarly edition of a Persian tale called “The Three Princes of Serendipp,” the story of three brothers from Ceylon who show remarkable powers of perception during their travels. It was from this story that Horace Walpole derived the word serendipity, which has come to mean a chance discovery or fortuitous event.

As a Jew, Benfey was never accorded the scholarly positions or the salary that his reputation deserved, even after his token conversion to Christianity in 1848. Financial difficulties and professional humiliations (specifically, the university’s continuing

Theodor Benfey

refusal to promote him to the rank of full or ordinarius professor until 1862) are running themes in the biography written by his daughter Meta. In 1859, the year in which he published his landmark edition of the Panchatantra, Benfey began taking in English pupils to make extra money. The most famous of these, the moral philosopher Henry Sidgwick, wrote in 1864, “Professor Benfey is a great talker, and the more I see of him the greater respect I entertain for his ability. He is not at all a man who impresses one with ability at first,” he added, “but he has wonderfully quick and accurate perceptions, astonishing powers of work, unfailing clearness of head.”

Sidgwick was particularly taken with Meta Benfey. “I only wish I could devote more of my time to the improvement of my German by conversation with her.” According to Bart Schultz’s biography, Sidgwick’s sexual tendencies ran to homosexual “Greek love,” and his attraction to Meta—“intelligent, enthusiastic, and not ugly”—constituted an early and confusing crisis in his sexual identity.

Benfey’s major scholarly contribution was in the field of fairy tales, closely associated with Göttingen because Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm taught German philology there. While the ardently nationalistic Brothers Grimm insisted on the Germanic and “peasant” origins of the tales they assembled in their collections of Märchen, Benfey, more cosmopolitan in his intellectual instincts, was struck by the many similarities between European fairy tales and mythical tales from other lands, especially Arabia and India.

Benfey’s international fame rested on his bold theory, arrived at intuitively and announced in his commentary on the Panchatantra, that all European fairy tales had their origins in Buddhist and Hindu myths from India, and that these tales had migrated westward, via oral and written transmission, to Europe.

Benfey challenged two bedrock convictions dear to the Romantic generation of the Grimms: first, that folktales were the fossil remains of Old German myths, and second, that they were orally transmitted. “Out of the literary works,” Benfey wrote in his introduction, “the tales went to the people, and from the people they returned, transformed, to literary collections, then back they went to the people again, etc., and it was principally through this cooperative action that they achieved national and individual spirit—that quality of national validity and individual unity which contributes to not a few of them their high poetical worth.” Benfey noted, for example, that an Indian story about the Buddha, garbled in transmission through Arab lands, had resulted in the canonization of the Bodhisattva as St. Josaphat.

Benfey’s theory of Indian origins appeared in 1859, the same year as the publication of Darwin’s theory of natural selection in The Origin of Species. The two theories have some striking features in common. Both point to a common ancestry for later variations; both argue that earlier forms—whether of species or of stories—migrate and adapt to new habitats. According to the Harvard medievalist Jan Ziolkowski, “Benfey’s view of India as the reservoir of stories from which European folktales derived exercised considerable influence throughout Western Europe in the second half of the nineteenth and early part of the twentieth centuries.”

While Benfey sought a single origin of fairy tales, adopting what Ziolkowski calls a model of monogenesis and diffusionism, alternative hypotheses of polygenesis were subsequently proposed. The idea of multiple origins can be based on psychoanalytic notions of universal “elemental ideas,” whether derived from Jungian archetypes or Freudian family traumas. An alternative model of polygenesis was adopted by the British anthropological school, associated with Andrew Lang and Sir James Frazer and later with such works as T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land. “Its exponents maintained that all human cultures developed according to the same course,” Ziolkowski writes, “and that, as a result, they might forge similar or even identical tales in response to similar needs, pressures, and desires.”

For roughly a century, folklorists have given more attention to structural similarities among divergent tales than to their elusive origins. But there has been a recent trend toward reopening the question. In his book Fairy Tales from Before Fairy Tales, Ziolkowski seeks to rectify a puzzling omission in fairy-tale research: the corpus of medieval Latin texts dating from circa 1000 to 1200, many of which have an obvious bearing on the transmission of fairy tales. Ziolkowski argues that the close historical link between fairy-tale research and literary nationalism partly accounts for the omission; collectors like the Grimms were reluctant to admit that Latin, a “supranational,” cosmopolitan, and literary language, might be the repository of fairy tales.

Ziolkowski has made the startling discovery that the Grimms drew freely from these Latin texts, “Germanizing” them in the process. In tracing the strange travels of one such tale, which the Grimms called “The Donkey,” Ziolkowski proposes to “revive and modify for application” Benfey’s “Indianist or migrational theory,” which he summarizes as follows:

From the Indian subcontinent, the tales had been transported, after the advent of Islam, first to Persia and then to the whole of the Arabic-speaking Muslim world. According to Benfey’s theory, the tales eventually wended their way to the Latin West, through border zones in Spain and Sicily as well as through the Crusaders.

Ziolkowski explores three variants of “The Donkey.” In the earliest version, in Sanskrit, a Hindu god is punished for his lust by having to assume the form of a donkey. Though he lives in the family of a humble potter, the donkey marries a king’s daughter. He is released from his bestial form when his mother-in-law burns the ass’s skin he takes off at night, when making love to the princess. The Sanskrit myth undergoes its own metamorphosis in a medieval Latin poem, in which the donkey is no longer a god in disguise but a king’s son, who despite his bestial form becomes a gifted lute player and wins the love of a beautiful princess. The Grimms retained the lute—“your fingers are surely not made for that,” a minstrel tells the donkey—but excised the eroticism of the Sanskrit and Latin versions.

One puzzle among the successive versions of the tale is the insertion of music making. Ziolkowski proposes an ingenious solution. He thinks that musicians were the carriers of the tale from Asia to the West, and “grafted” themselves into the story. He concludes that the Sanskrit myth “passed into regions where Hindu gods were not worshiped and where their functions in the story had to be suppressed or altered and that the carriers of the tale, the entertainers who had transported the story into their repertoires, grafted themselves and their art into the tale as a way of endowing it with a new raison d’être.”

12.

Many of the fairy tales that Theodor Benfey explored are about perilous journeys. And meanwhile, according to Benfey, the tales themselves had embarked on dangerous voyages, traveling in the books and the memories of exiles on the move, wandering westward in search of better lives. It occurred to me that Benfey may well have associated such migrations with his own Jewish background, and the wanderings of persecuted Jews over the centuries. It is a bitter historical paradox that Benfey’s theory of Indian—or, as it was known then, Aryan—origins of German fairy tales became part of the matrix of pseudo-Aryan mythology that buttressed Hitler’s fantasies of German greatness.

But what about the supposed link—commemorated in the snuffbox—of the Benfey family to Apollo? How exactly did this particular theory of origins come into existence? Theodor Benfey’s father, who belonged to the first generation of German Jews required to have family surnames, called himself Isaak Philipp Benfey (1763–1832). Isaak’s father was known simply as Feistel Dotteres, sometimes Hellenized in nineteenth-century documents as Philipp Theodorus. There’s nothing about Feibisch or Phoebus in any of these documents, but I found the divine ancestry in Meta Benfey’s biography of her father. “In intimate circles,” she wrote, “he often expressed the opinion that his ancestors must have spent a good deal of time in Greece, and might even have had an admixture of Greek blood in their veins.” As evidence, according to Meta, he pointed to the many Greek names in the family: “his own name, Theodor, that of his eldest sister, Simline (= Semele), that of a brother, Philip, and of his grandfather, Feibisch (= Phoebus).” When the Jews were required to take surnames, according to Meta, Benfey’s father chose the name Benfeibisch, meaning “son of Feibisch.” “Luckily,” Meta remarks, “the authorities thought the ugly name was too long and struck the last syllable.”

Here, then, was the theory of our family name in its full blossoming. I didn’t want to put too much pressure on the slippage between Feistel, the documented name of Theodor Benfey’s grandfather, and this sudden emergence of Feibisch. Nor did I want to worry overmuch about how Feistel had miraculously metamorphosed (either through Meta’s ingenuity or Theodor’s) into both Philip and Phoebus. What fascinated me was that I had heard this Feibisch-Phoebus connection before, in a poem of migration and exile by Heinrich Heine.

Heine’s poem is called “Der Apollogott,” or “The God Apollo,” and was written around 1849, when Heine was ill and living in exile in Paris. In the first part of the poem, a nun is sitting in her cloister room high above the Rhine and hears beautiful singing from a little boat on the river. She is astonished to see the handsome god Apollo himself, wrapped in his scarlet cloak, singing and playing his lyre to the nine admiring Muses. In the second part of the poem, he sings about his fate. Driven out of Greece (“verbannt, vertrieben”) like the other pagan gods, he is seeking a better home in exile. In the third part, the young nun leaves her cloister and follows the road to Holland, asking everyone she meets if they have seen the god Apollo.

Finally, the nun comes across a slovenly old peddler trudging down the road. “Seen him?” the man replies to her query. “Yes, I’ve often seen him in Amsterdam, in the German synagogue.” He explains that Apollo was the cantor there, and was known as “Rabbi Faibisch, / Was auf Hochdeutch heist Apollo”—“Rabbi Faibisch / Which means Phoebus in High German” (actually Yiddish). Faibisch’s father, the old man remarks, circumcises “the Portuguese”—Sephardic Jews—while his mother sells sour pickles at the market. The old man explains that Faibisch has quit his job as cantor, is now a freethinker who eats pork and roams the countryside with a comedy troupe:

Recently he took some harlots

From the Amsterdam casino

And with these alluring Moses

Goes around as an Apollo

Here was the same equation of Faibisch (or Feibisch) and Phoebus that Theodor Benfey had found in his own name of Benfey or Ben-Feibisch. So, where did Heine get his Faibisch-Phoebus link? Heine scholars report that around 1850, Heine supposedly addressed Ludwig Wihl—a Jewish poet and journalist who had written a collection of India-tinged verses titled Westöstliche Schwalben (Swallows of West and East)—as Monsieur Faiwisch (Phoebus). But this hardly seems an explanation, as Wihl sounds nothing like Faiwisch; rather, the anecdote suggests that Heine saw something “Indian” or “East-West” in the Feibisch/Phoebus connection.

Benfey and Heine shared some of the same scholarly interests and training. During the early 1820s, Heine, like Benfey a few years later, had studied Sanskrit with Franz Bopp, in Göttingen and Berlin, and he shared Benfey’s intense interest in fairy tales. Heine’s Apollo poem is suffused with the language of myths and fairy tales. Apollo’s little boat on the Rhine gleams “märchenhaft”—“as in a fairy tale”—in the setting sun, and his song is set to the traditional meter of a folk ballad. The story of Apollo’s descent into the streets of Amsterdam, moreover, bears a striking resemblance to the kind of story Ziolkowski describes in his versions of the donkey tale, in which a god assumes earthly form and becomes an itinerant musician.

Were Heine and Benfey acquainted? It seems likely that they were. The Dartmouth philologist Walter Arndt (an old family friend, since my German grandmother hired his wife to work at the Window Shop in Cambridge) sent me a report from 1995 of the discovery of an oil portrait of Heine, hitherto unknown to scholars, that had turned up in Theodor Benfey’s belongings—an indication of admiration, if not necessarily intimacy. There was, in addition, at least one direct connection between Heine and the Benfey family. Theodor’s eccentric brother Rudolph, a freelance writer and a socialist, was a close associate of Heine (and of Karl Marx) in Paris. Is it possible that Rudolph had shared with Heine the fanciful Greek origins of his own last name, as told to him by his brother Theodor?

13.

It slowly dawned on me that my snuffbox-inspired search for the origin of Phoebus and Feibisch resembled the quest for the origin of fairy tales. Instead of monogenesis and diffusion, could this suggestive pairing of names be an example of polygenesis? The scholar Norbert Altenhofer discovered a German novel of 1834, Der jüdische Gil Blas, in which there is a Rabbi Feibisch who is linked to Phoebus. David S. Katz, in The Jews in the History of England, 1485–1850, mentions the Hart brothers from Hamburg, who settled in London around 1700. The elder brother, a rabbi, was known as Uri Feibush/Phoebus or Aaron Hart. “In rabbinical practice,” according to Alexander Beider’s Dictionary of Ashkenazic Given Names, “the name Fayvush and its variants were generally considered as derived from the Greek name Phoibos (Latin Phoebus), god of the sun. This erroneous etymology is also suggested by several linguists…” According to Beider, the actual origin of the name Fayvush is not the Greek Phoibos but the Latin vivus, meaning “living” or “alive,” a name that moved eastward from France and—the Sephardic hope again!—Spain.

It seems quite likely that the Feibisch-Phoebus equation was already proverbial in Heine’s time and ripe for the distinctive mixture of pathos and satire that Heine brought to his Apollo poem. For Heine, and no doubt for the brothers Benfey as well, there was a close and moving analogy between the Greek gods in exile and the persecuted Jews. Heine’s Apollo sings of his lost temple that stood on “Mont-Parnass” in Greece; in giving the name in French, he alludes to his own exile in Paris. Benfey’s belief that there was Greek blood in his veins is typical of his Hellenizing generation of assimilated German Jews.

Of course, there was more than a little Jewish self-hatred in these stories of Greek origins and Sephardic identity, but I prefer to put the emphasis—as Benfey himself did in his scholarship—on migration and self-renewal. The truth of such origins—in surnames and fairy tales—is probably closer to Benfey’s own theory of Indian origins. Names of Hindu and Greek gods traveled westward, picking up new associations and narratives. Bodhisattva became Josaphat; Faibisch merged with Phoebus.

Horace Walpole, in a letter of 1754, tried to define his new word serendipity. He had once read, he said, “a silly fairy tale” about the princes of Serendipp: “as their highnesses traveled, they were always making discoveries, by accidents and sagacity, of things they were not in quest of… now do you understand serendipity?”

The god of artistic creation, of music and of poetry, carries many names and travels through books and memory, on foot or in his little boat. He travels up the river to the cosmopolitan city, where he sings to the congregation. Then he assumes a new guise, and it is as an itinerant artist, an actor, that we see him next. Both god and fraud, visionary and vagrant, Phoebus and Faibisch, he is an artist of serendipity, of adaptation and self-invention. He is still on the move.