1.

In January 2008, after several earlier plans had fallen through, I finally had a chance to drive out to Black Mountain. The timing was good. I was in Greensboro, visiting my parents, and I had agreed to teach a course that spring on some of the major figures at the college—Josef and Anni Albers, John Cage, Karen Karnes, and Buckminster Fuller—and their impact on American art and society. My older brother Stephen happened to be in Greensboro as well, visiting from his home in Tokyo. He was eager to make the trip with me. The college had been closed for several decades, however. At best, we would be visiting ruins, hoping to find some vestiges of the school, some surviving sign that the landscape was still haunted by those towering presences that had given Black Mountain its legendary status in the history of American education and avant-garde art.

Black Mountain had seemed almost a mythical place during our upbringing, a tether linking our flat Midwestern childhood to the vivid summits of artistic innovation and adventure. A painting by Juppi, as Josef Albers was known in our family, had hung in our dining room when my brothers and I were growing up in Indiana. It was a bold, Mexico-inspired abstraction in red and black from the early 1940s. Our father’s sister, Renate, had attended Black Mountain, living with the Alberses. Some of the refugees from Black Mountain, after it fell apart during the 1950s, had ended up at the Quaker college in Indiana where our father taught chemistry. I remembered Ray Trayer, who ran the farm there after leaving Black Mountain. As a child, I associated him with the cottage cheese we picked up at the farm, which I mistakenly thought was “college cheese.”

We had even visited the Alberses once, in 1960, at their simple, split-level house in New Haven. My mother had brought along some of her own paintings, ambitious abstractions completed under the tutelage of an Austrian teacher, which appeared stained into the canvas rather than painted onto it. The paintings that she showed to Josef Albers that day were suggestive of orange-tinged clouds at dawn, swirling water, uneasy dreams. They had nothing in common with his clean-edged abstractions, in which all the drama resulted from where two distinct and carefully applied colors touched. For Albers, everything in a work of art should be the result of deliberate and conscious decisions.

On such social occasions, Anni, ridiculously, played the dutiful housewife, wheeling in the tea and German cookies on a Bauhaus tea cart. Then she sat to one side, as though awaiting orders from the master of the house, who was courtly and flirtatious until the paintings themselves were brought in from the car. Josef Albers disliked anything that reeked of self-expression; he thought of art as an escape from inner confusion and mere feeling. Art for him was a way of exploring the world out there, not the tangle of emotions inside all of us.

My two brothers and I sat on the floor in an adjacent room, pretending to play with some miniature Bauhaus architectural bricks, when the great man placed one of our mother’s paintings on the table. “What means this?” Juppi asked, pointing to a wavy area on one of the paintings. And then, jabbing with his thumb at another vulnerable motif, “What means this?” The paintings were hurriedly put away.

2.

Stephen and I had decided to drive straight to Asheville, where we could have some lunch, get directions, and orient ourselves. Then we would backtrack to the Lake Eden campus of Black Mountain College. I estimated that it would take us three or four hours, steadily rising all the way to the eastern outskirts of Asheville, where the hamlet of Black Mountain lies on one side of Interstate 40 and the Lake Eden campus on the other. We could spend a few hours of daylight wandering around the place, and still be back in Greensboro by nightfall. Our trip would be a commemorative pilgrimage of sorts. The school had shut down fifty years earlier, in 1957. By that time its student body, never much more than fifty, had dwindled to six, and its financial resources were approximately zero, if not already in the red.

As we drove west, we passed signs for the Biltmore Hotel, a reminder that Asheville has been a resort for vacationing Yankees since at least the 1890s. Modeled on a French château, the 250-room Vanderbilt mansion took an entire community of skilled craftsmen six years to build. The estate, on 125,000 rolling acres laid out by Frederick Law Olmsted, had its own brick factory, using the abundant red clay from the local riverbeds, and a three-mile railroad spur to bring building materials to the construction site.

As we drew closer to Asheville, however, the surroundings didn’t look particularly luxurious. Billboards warned against the dangers of methamphetamine abuse and depicted, with nauseatingly explicit photographs, the dental disaster known as meth mouth. Notched into the hills were more signs of decay: dilapidated towns of abandoned shacks and trailer parks, rife, no doubt, with secret methamphetamine labs. We stopped for gas at a convenience store off the highway. Inside, by the cash register, there was a rotating display case for knives. I had never seen anything like them. They weren’t hunting knives or kitchen knives; in fact, they seemed to have no obvious use at all. They seemed more like fantasy knives—scimitars and halberds—decorated with sinister swastikas and Masonic devices.

In Asheville, on the handsome main street with its brick storefronts from the 1890s, we had lunch at an all-you-can-eat Indian restaurant. Our waitress, a moonlighting actress, told us that she had the Audrey Hepburn role in a local production of Wait Until Dark, the gothic thriller about a blind woman and the thugs who try to retrieve heroin hidden in a doll. The waitress came from Franklin, North Carolina. I asked her why she had decided to live in Asheville. “Have you ever been to Franklin?” she asked. I told her that I planned to do some research in Franklin during the summer, concerning some mysterious deposits of white clay. She thought I was joking.

Back on the road, with a local map we’d picked up in Asheville, we zigzagged off the Interstate and into a maze of local streets down in the valley below Black Mountain. We followed the map past the forlorn Creole Court trailer park and looked for a “big fence,” the next landmark, where we were instructed to turn left onto Lake Eden Road. The fence, a concave spiderweb of rusting wire, turned out to enclose a detention center for delinquent boys.

Another turn and we entered a less sinister world. A well-groomed road lined with stately pines led us to the serene lake, festooned with faded lilies, where the landscape opened and we had a clear view of the low-lying Study Wing, the most familiar Black Mountain College building. In the distance, the black mountain itself rose up from the pines. Amid the January stillness, I had a momentary impression of being in Japan. I remembered something from Henry Miller’s visit to the school during the 1940s, when he was crisscrossing the South on his “air-conditioned nightmare” tour. “From the steps of Black Mountain College in North Carolina,” Miller wrote, “one has a view of mountains and forests which makes one dream of Asia.”

Walking toward the streamlined concrete and fiberglass building, we could make out the two faded murals, ghostly in the winter light, that Jean Charlot had painted on its exterior pylons. A French artist with a Mexican mother, Charlot had been Diego Rivera’s assistant in Mexico City during the 1920s. Albers invited him to teach at Black Mountain, where he painted the murals during the summer of 1944. Strange hooded figures in cramped positions represent Learning and Inspiration.

We hadn’t bothered to call before, but Jon Brooks, the codirector of Camp Rockmont, a Christian summer camp for boys, welcomed us warmly when we mentioned that we were grandnephews of the Alberses. We signed the visitors’ book, a few lines after Allen Ginsberg, who had visited Black Mountain on his own pilgrimage. Brooks led us down the hall, past individual student studios. He pointed out how the wallboards overlapped, so that student carpenters could make mistakes in measurement without compromising the overall design. Then we descended downstairs into the dark, musty room where Anni Albers had her looms and where pottery wheels now lined the floor like votive presences. This dank underground space, Brooks said, was now called the Anni Albers Studio.

4.

With the dusky afternoon light filtering down the darkened staircase, it suddenly dawned on me, with an emotional impact I hadn’t expected, that we were actually standing in the space where Josef and Anni Albers had taught. It was here that Anni led her students to discover what she called, somewhat mysteriously, “the event of a thread.” I had sometimes imagined her as a modern Ariadne with her magic thread, leading the way out of the Labyrinth.

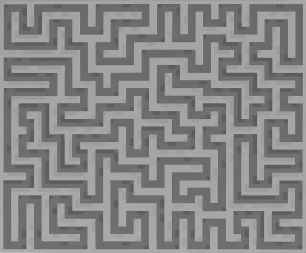

Though both Josef and Anni prided themselves on their modernist orientation, there was also a contrary tendency in their work, toward the primitive and the archaic. Their own teaching was a creative fusion of the deep past and the vivid present; it was the more recent European past that they silently skipped over. They were particularly drawn to ancient patterns, which they invited their students to explore. In his book Search Versus Re-Search, for example, Josef devoted a whole section to the pattern, one of the oldest in human history, known as the meander or Greek key.

Frequently found on the borders of pottery and textiles, the meander resembles a maze or labyrinth. When European artists during the eighteenth century fell in love with vases dug from the ruins in Herculaneum and Pompeii, they adopted the meander found on the rims and shoulders of many of the vases. For neoclassical potters like Josiah Wedgwood, the meander was almost a trademark, linking their works with antiquity.

The meander pattern

For Josef and Anni Albers, however, the meander was a quintessentially American shape. “Nowhere has it been cultivated more through all periods,” Josef noted, “than by the Amerindians from the northern Tlingits to the most southern Araucanians, in building, sculpture, painting, and particularly in weaving and pottery.” After their arrival in America, the Alberses came to see the meander as an emblem of their own winding path through the world.

The meander confirmed the Alberses’ interest in the ambiguities of human vision. One was never quite sure whether the pattern was made by the line itself or by the surrounding spaces it created. It was both intricate and simple:

Intricate because of its figure-ground relatedness in which figure and ground are simultaneously and alternately theme and accompaniment, thus guiding and following each other. Simple, when we discover that the underlying unit measures an alternating decrease and increase in the extension of the lines.

With its strenuous economy of means, the meander fulfilled the less-is-more Bauhaus aesthetic. “Virtually only one line is done,” Albers wrote, “but the adjacent ground, accompanying its movement, transforms its one voice into two, three, and more voices and echoes.” In Anni’s beautiful Red Meander, the pattern is doubled, as though the serpentine path is shared. Meanwhile, the resulting composition, with its illusion of depth, looks like a maze viewed from above, and the eye restlessly wanders the red and pink passages, looking for entrances and exits.

Anni Albers, Red Meander, 1969

It was the Roman poet Ovid, in the eighth book of his Metamorphoses, who first compared the famous Labyrinth on the island of Crete to the winding river in Asia Minor named the Meander. Ovid retold the story of Minos, ruler of Crete, and the dangerous passion that his wife, Pasiphaë, conceived for a white bull from the sea. In order to attract the bull, she had the master craftsman Daedalus construct out of wood a hollow and alluring cow that she could crawl into.

The hybrid offspring of their unnatural coupling, part human and part bull, was named the Minotaur. Daedalus was prevailed upon to hide this family embarrassment in the elaborate twists and turns of the Labyrinth, part prison and part refuge:

Minos resolved to remove this disgrace from his home

and to shut it in a convoluted house, concealed in darkness.

Daedalus, most celebrated and skilled of craftsmen,

constructed the building, adding confusing marks,

which, through the crooked windings of many different paths,

led the eyes into uncertainty.

What follows is known as a Homeric simile, a long and winding comparison of the kind found in Greek epic poems:

Just as the clear-watered Meander frolics in the Phrygian

fields,

and slipping about flows back and forth, and running into

itself

sees approaching torrents, and, turning now back to its source

and now to the open sea, drives its unsettled waters on,

in just the same way, Daedalus filled his maze

with countless winding paths. Even he was barely able

to grope his way back to the entrance,

so mighty was the trickery of his structure.

Tanta est fallacia tecti. Daedalus had at least two more “fallacious” tricks up his sleeve. One was the ball of thread, the famous clew, or clue, that Ariadne, daughter of Minos and Pasiphaë, entrusted to the Athenian hero Theseus, along with a sword, so that he could find his way out of the Labyrinth after killing the Minotaur, Ariadne’s own half brother. Theseus and Ariadne then fled the island kingdom of Crete, and Theseus abandoned Ariadne on the island of Naxos. Daedalus decided that he, too, was tired of Crete and, according to Ovid, was “longing to see his native land.” So Daedalus outfitted his son Icarus and himself with wings made of feathers and wax and twine and taught him to fly. Hence the epigraph from Ovid that James Joyce appended to A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, in which the hero is called Stephen Daedalus: Et ignotas animum dimittit in artes, “He now turns his mind to unknown arts.”

In the story of the Labyrinth, almost everything goes wrong. Icarus, in the ecstasy of flight, flies too close to the Sun, melting the wax that holds his wings together, and tumbles back to Earth. Forgetful (immemor) Theseus, who forgets Ariadne on Naxos, also forgets to change the sails on his ship from black to white. This was the agreed-upon signal to inform his father that he has killed the Minotaur. His father, in despair, throws himself from the cliffs to his death.

All that remains, after the violence and the deception, is the pattern itself, the meander designed by Daedalus, the supreme artist of transformation. The pattern first informs the walls of the Labyrinth, then the thread unwound within it, and finally the dance that Theseus performs to celebrate his triumph.

7.

Another artificer, Hephaestus, the Greek god of craftsmen, depicted this dance on the famous shield that he made for Achilles, as Homer describes it in the eighteenth book of the Iliad:

Here Hephaestus, famous and lame, inscribed a dance floor that resembled what Daedalus once fashioned for fair-haired

Ariadne

in far-stretching Knossos. Youths and much-courted maidens

dance there,

hand to wrist. The maidens wear garments of fine linen, while

the youths

have flowing, well-spun tunics on, with a slight olive-oil

sheen;

the ladies sport handsome head-dresses, while the young men

carry golden daggers in silver belts.

Again the passage ends with a striking simile:

At times they run about with great facility,

on skilled feet, just as a seated potter, fitting his hands around

his wheel,

tests whether it will turn.

I love how Homer brings several arts into his description of Achilles’ shield, how effortlessly he moves from Ariadne with the lovely hair to the dancing girls and then, suddenly, to the potter testing his wheel with his skilled hands. The potter at the wheel is for him the ultimate image of balance, consummate precision, and graceful turning.

8.

Stephen and I lingered at Black Mountain as the shadows lengthened. We were both reluctant to leave. We wandered along the barren paths looking for the wooden house where the Alberses had lived. Then we poked around in the darkening woods and finally found Alex Reed’s Quiet House, now with an added second story and a new roof. During these forays on the site of what had once been a vital and creatively intense community, I was groping for a metaphor to capture the proceedings. I wanted a dominant form that would somehow link our own zigzag path with the artistic concerns of the Alberses. As we began to retrace our route through the maze of streets near Black Mountain, I realized that the key had been there all along, in the meander pattern so dear to Josef and Anni.

9.

Driving back to Greensboro that night, following the looping highway, I first heard about Ruth Asawa’s work. On his way from Tokyo to North Carolina, Stephen told me, he had stopped over in California to visit his two Japanese American daughters, my nieces, who were studying in art schools there. Together, they had gone to see an exhibition of Asawa’s work at the de Young Museum in San Francisco. I recognized, as I learned more about her during the days and weeks that followed, that Asawa was an important link to the Alberses, as well as to our own Quaker and Japanese affiliations. Her difficult and triumphant life had an underlying pattern that felt familiar. It became clear to me that Asawa was one of the students at Black Mountain College who had learned the lesson of the meander, in art and in life, from Josef and Anni Albers.

Another child of dislocation, Asawa had grown up in a poor farming community in Southern California, one of seven children of Japanese immigrants. Her father had come from Fukushima prefecture, not far from Tokyo, where he had been an itinerant farmer. He would walk through the streets calling, “Beans and tofu, beans and tofu!” In California, he schooled his children in calligraphy and kendo, a traditional martial art practiced with bamboo swords, with the idea that they would eventually return to Japan.

As a child, Ruth had shown artistic talent; she won a competition in 1939, when she was thirteen, for a drawing of the Statue of Liberty. After the bombing of Pearl Harbor, Asawa’s father was arrested by the FBI and placed in a hard-labor camp in the Southwest. She did not see him, nor did the family hear from him or know of his fate, for six years. The rest of the Asawa family was among the 120,000 Japanese Americans on the West Coast who were ordered to leave their homes and report immediately to detention centers and internment camps for the duration of the war.

The first destination of the Asawa family, in April 1942, was the Santa Anita Racetrack, where they lived in horse stalls, still reeking of Thoroughbreds, for six months. Among the thousands of detainees crowded into the racetrack were several Japanese artists, some of whom had worked as animators at the Disney Studios. They established a makeshift art workshop in a section of the Santa Anita grandstand, and Asawa studied there. “How lucky could a sixteen-year-old be?” she reflected later. The prison had become a sanctuary.

10.

This strange idyll was interrupted when the Asawa family was shipped by train to an internment camp in Arkansas. The children attended school at the camp, where they were required to recite the Pledge of Allegiance. After the words “with liberty and justice for all,” Asawa and her friends added, “except for us.” Asawa’s ability in art was noticed, and she received a scholarship from the Society of Friends, the Quakers, who took a strong interest in the well-being of interned Japanese Americans. She studied at a teachers college in Wisconsin but learned there was no possibility for a Japanese American to teach there.

Drawn by the murals of Diego Rivera and his associates, Asawa spent the summer of 1945 studying art in Mexico. She watched José Orozco at work and took lessons in fresco painting. She also worked in Mexico with a Cuban-born furniture designer named Clara Porset, who urged her to enroll at Black Mountain College and study with Porset’s friend Josef Albers.

Asawa found a new view of life and art at Black Mountain. At first, she planned to study weaving with Anni Albers, who sent her to Josef’s design class instead. There she learned about handling materials. “Every material has several voices,” she wrote in her notes for one of Albers’s classes. “Let’s find out different possibilities.” She was fascinated by the class exercises in the juxtaposition of materials, finding ways of making one thing resemble a very different thing. “Leather = peanut butter,” she wrote in her notebook. The whole ethos of the class, making art out of leaves and other found objects, suggested a morality based on scarcity, sustainability, and the avoidance of waste. One of her favorite maxims from Albers was: “Get 5 cents from 3 cents.” Scrawled across a class exercise on the meander pattern, she wrote: “Do one get two.” She also liked how Albers used analogies from Taoism and other Asian philosophical traditions.

Summers were particularly vivid at Black Mountain, bringing extraordinary artists and thinkers to the campus. Albers invited two artists to spend the summer of 1946 at the college. One was the African American painter Jacob Lawrence, soon to paint his great series of scenes on the diaspora of black people from the agricultural South to the cities of the North. Albers hired a separate coach for Lawrence and his wife on the train to Asheville so that they would not have to sit in the Jim Crow car. Asawa enjoyed attending the classes of Jean Varda, a charismatic Greek artist who had worked in Paris before the war. Varda talked incessantly of Greek mythology and “the mysteries of the labyrinth.”

The years in which Asawa was at Black Mountain, 1946 to 1949, were among the most creatively vital in the history of the school. It was during these years that a fertile transition began to take place, from the European émigrés who had brought the ideas of the Bauhaus, Brecht, and Schoenberg to the campus, to the homegrown Americans who were eager to push such possibilities even further. The composer John Cage and the choreographer Merce Cunningham were barely known when they performed at Black Mountain in 1948, bringing natural movement and ordinary sounds onto the stage. (Only when Cage began introducing chance combinations into his compositions did Albers object.) Buckminster Fuller, who erected his first geodesic dome at Black Mountain, was known as an eccentric designer but little else.

It was immediately clear to Albers that these brilliant young artists were doing things with movement and sound and structure that paralleled his own experiments with color and materials. The aim—a very democratic and American aim—was to eliminate prejudice against certain colors or sounds or kinds of movement, to corral them all into artistic “making,” to “find out different possibilities.”

Asawa’s mature work, as she developed it in San Francisco during the 1950s, was a sustained engagement with procedures begun during the Black Mountain years. She had spent the summer of 1947 in a village outside of Mexico City, sponsored by the American Friends Service Committee. Josef and Anni were also in Mexico that summer on sabbatical, and they traveled with Asawa and looked at their friend Diego Rivera’s murals together.

Back in her village, Asawa was fascinated by the wire baskets made by local women, who used them to carry fruits and vegetables to market. That summer, she learned from them to knit with packing wire, a cast-off material of the kind favored by the Alberses. She discovered ways to make a continuous line of wire take on thickness, as it was looped and threaded, and then volume, as the single thread of wire was knitted into a vessel. Another influence was Japanese pottery, with its long tradition of humble aesthetics; she saw Shoˉji Hamada, the great Japanese folk potter, make pots in California during his 1952 tour of the United States.

Imogen Cunningham, Ruth Asawa’s Wire Sculpture, 1954

12.

Already in Josef Albers’s classes, Asawa had conceived a passion for the meander pattern and its shifting rhythms of figure and ground. Jean Varda had pushed her further, to think of threads and labyrinths. Now she found in wire thread a way to develop the meander in three dimensions. Soon she was making the hanging, basketlike forms that she is best known for, as though Ariadne’s thread had woven the labyrinth. A photograph by Imogen Cunningham captured Asawa as Ariadne, entangled in her web.

Imogen Cunningham, Ruth Asawa, Sculptor, 1956

13.

Stephen’s remarks about Ruth Asawa had made me want to know more about her. But it was only much later, a year after the visit to Black Mountain, that I was able to experience Ruth Asawa’s work firsthand. I first saw her wonderful hanging globes and baskets in San Francisco, during the summer of 2009, in the tower of the de Young Museum in Golden Gate Park. My wife and I had traveled there with our younger son, Nicholas, who was sixteen at the time. I wanted to see as much of Asawa’s work as I could during the visit. We saw the flamboyant bronze fountain that she had made as a tribute to San Francisco, with miniature streetcars and bridges, and the bronze plaque with its sculpted frog in the Japanese Garden in Golden Gate Park. It was mainly the wire baskets and globes that I wanted to see, however, and I was grateful for the generous installation in the de Young tower.

Something strange happened to me that summer in my encounter with Asawa’s art, a mushrooming tangle of associations that began with fairy tales and then looped back, like a meandering thread, to the myth of the Minotaur and the Labyrinth.

We had flown across the country in July, on the day that Michael Jackson died. Nicholas had brought along an old copy of tales from the brothers Grimm, to read on the plane. We were particularly fond of a story called “The Mouse, the Bird, and the Sausage,” and especially this line from the first paragraph: “Nobody is content in this world: much will have more.” But it was rereading “Hansel and Gretel” that stuck with me for the entire trip west. Here is how the story begins:

Hard by a great forest dwelt a poor wood-cutter with his wife and his two children. The boy was called Hansel and the girl Gretel. He had little to bite and to break, and once when great dearth fell on the land, he could no longer procure even daily bread. Now when he thought over this by night in his bed, and tossed about in his anxiety, he groaned and said to his wife: “What is to become of us? How are we to feed our poor children, when we no longer have anything even for ourselves?” “I’ll tell you what, husband,” answered the woman, “early to-morrow morning we will take the children out into the forest to where it is the thickest; there we will light a fire for them, and give each of them one more piece of bread, and then we will go to our work and leave them alone. They will not find the way home again, and we shall be rid of them.”

The story had always troubled me, with its disturbing theme of abandoned children. Perhaps it evoked my sense of my father’s interrupted life. But during our stay in San Francisco, I couldn’t get it out of my mind, and my thoughts about it began to blend with my response to Ruth Asawa’s work. I kept thinking about Hansel’s path of pebbles, the children’s escape route from the forest.

14.

I would wake up early each morning in our small hotel in North Beach, hard by the City Lights Bookstore, and mull over some aspect of the story. I thought about Hansel’s trail of pebbles in the moonlight or his father’s mysterious motivations in abandoning his children in the forest, and ideas came unbidden to my mind. Sitting in the Caffè Greco, across from our hotel, I began jotting things down in my notebook. “Hansel and Gretel is the story of a father who cannot provide for his children,” I wrote in the first entry. “When you cannot feed your children, they are taken away from you. Think of orphanages, foster homes, animal shelters. All of these sanctuaries can seem like prisons or cages, like the Labyrinth.”

I hadn’t realized how much of the story was centered on food. There isn’t enough food to go around, so the children, with “one more piece of bread,” must be sacrificed. The birds eat the breadcrumbs that Hansel, the second time they are abandoned, substitutes for pebbles. The children find a house “built of bread and covered with cakes,” with windows “of clear sugar,” and they start nibbling on the roof and window panes. The old woman who lives in the house fattens up Hansel so that she can eat him.

No less conspicuous in the story and often linked to the incessant eating is the element of trickery, one clever stratagem following another. The children secretly eavesdrop on their parents’ treacherous plans. Hansel sneaks out to get pebbles to mark the way back home. As the children sit by the fire the first night out, they hear what they think is the reassuring striking of their father’s ax. “It was not the axe, however, but a branch which he had fastened to a withered tree which the wind was blowing backwards and forwards.”

There are more tricks. The old woman’s edible house is a deceptive lure to entrap the children. (From my notebook: “The edible house is the bait, like a worm on a hook. The hooked fish was thinking of dinner. But he wasn’t planning to be dinner.”) With a chicken bone masquerading as his finger, Hansel fools the old woman into thinking he’s not getting any fatter. And Gretel, clueless until that moment, asks the old woman to show her how to crawl into the hot oven, then slams the door shut.

15.

There are strange parallels between “Hansel and Gretel” and the story of the Minotaur. Both stories involve disorienting mazes, whether labyrinths or forests, inhabited by insatiable monsters. Both involve the sacrifice of children to those monsters, the bond of brother and sister, and the winding path of escape—Ariadne’s thread or the path of pebbles. Both stories hint at exile, for the old woman and the Minotaur.

Has anyone stopped to consider the loneliness of the Minotaur? The shame of the family, an exile in his own country, a strange hybrid of man and beast, he roams the walls of his confusing house looking for love. No wonder Picasso identified with him, and based his famous Guernica on imagery that he had developed in his paintings and prints of the Minotaur.

But there was something else here as well, some bedrock ambiguity in the whole notion of the Labyrinth.

16.

I had been wondering what Ruth Asawa had learned from her mentors, Anni and Josef Albers, and I felt that I had begun to unravel it. My journeys to Black Mountain and San Francisco had deepened my sense of their relationship. I could see how prisons and refuges, danger and safety, kept changing places for these uprooted artists, the one becoming the other, like figure and ground. The racetrack at Santa Anita seemed a perfect example of this. It was the place where Asawa was imprisoned but also the place where she discovered her vocation.

And then I stumbled upon Graphic Tectonics, a series of drawings and prints that Josef Albers made at Harvard in 1941, when he took a leave from Black Mountain. These images look strikingly like mazes. The eye wanders vertically and horizontally, and then plunges along diagonals, even as the image itself seems to pulse inward and outward like an accordion.

The print Albers called Sanctuary is for me his central visual statement of the double meaning of the maze. It captures the ambiguity of a prison that is also a safe haven, a sanctuary, as the Labyrinth was for the Minotaur, as the racetrack was for Ruth Asawa, as Black Mountain College was for the Alberses. Are those windows staring out from a house, or the dark eyes of some solitary animal?

For Josef and Anni Albers negotiating a new country, America must often have seemed like a maze. They had traveled from Berlin at the height of its sophisticated glamour to this backwoods realm of mountains and pines and winding country roads.

Josef Albers, Sanctuary, 1942

They lived in it and thrived in it by welcoming the ambiguities and by seeing patterns in those figure-ground uncertainties. They handed on their “searches and researches” to their students, threads for escape, threads for weaving more patterns, more sanctuaries, more spellbinding works of art.