1.

The Northeast Kingdom is a sparsely inhabited region of mountains and lakes notched into the upper corner of Vermont, hard by the Connecticut River and the Canadian border. My friend Mark Shapiro and I drove up there—it really felt like up—one cold and overcast January day, with snow expected in the higher elevations. Our plan was to spend some time with the legendary Black Mountain potter Karen Karnes. Mark had done the drive many times before, helping Karnes, now well into her eighties, with the heavy lifting involved in firing her pots, sometimes in his own wood-fired kiln in western Massachusetts, and sometimes in hers. This time around, however, we were hoping that Karnes might give us an up-close sense of what the pottery scene at Black Mountain was like during the 1950s, when Karnes was a potter-in-residence there. We knew that Karnes had been a good friend of John Cage and other Black Mountain luminaries, and we wondered how pottery, so bound up with folk and national traditions, had fit into the avant-garde, try-anything mood of the place.

The highway unspooled like a black thread between the soft snowbanks, and the snow got deeper as we headed due north. Mark pointed out the groves of red pines planted during the 1930s, first by the WPA and then by conscientious objectors confined to work camps during World War II—serried rows of trees as regular as cornfields, now reaching maturity. We followed the Interstate along the Connecticut River as far as we could before branching off toward the silvery sliver of Lake Willoughby—“so long and narrow,” as Robert Frost describes it in a poem, “Like a deep piece of some old running river / Cut short off at both ends.” According to local legend, a secret underground channel connects Willoughby to Crystal Lake in Barton, a few miles away. We took the exit for the village of Morgan, with a population of not much more than six hundred people, where many of the houses are hidden in the woods.

Mesmerized by snow sifting down through the pine branches, we overshot the unmarked turnoff to Karnes’s driveway and, braking hard, skidded in Mark’s blue Prius on the slippery pavement. Karnes’s longtime partner, an Englishwoman named Ann Stannard, met us at the door of the simple wood cottage set in a meadow with a view out to the mountains in the distance. Soft-spoken, orderly, and attentive, Ann used to throw pots but now spends her time as a Sufi teacher. As Karnes came out to greet us, Ann headed for the kitchen to finish preparations for lunch.

My first impression of Karen Karnes, as we headed down to her studio, was of silence, simplicity, and something deeply rooted. With her back bent by scoliosis and her slightly inscrutable smile, she reminded me of certain Buddhist figures. She answered my glib questions about her life and work with patient attempts at real answers. The large studio was well lit, with big windows looking out to the snowy meadow, and impeccably neat. There were two pottery wheels surrounded by drying shelves, with small objects—seashells, pre-Columbian figures, pebbles—placed on the windowsills for inspiration. We looked at some of her recent work. She resisted verbal interpretation of what was going on in these wood-fired pots, with their

Karen Karnes glazing, Black Mountain College, 1953

heightened blue and orange glazes, their multiple slits and mouths, their bulges and collapses. “Sometimes,” she told me, “there are things that don’t have words.” It seemed almost an article of faith with her.

The conversation continued over lunch—a rich lentil soup served in one of her trademark flame-proof casserole pots. A big yellow painting by her friend Mary Caroline Richards, another potter and Black Mountain teacher, hung by the dining-room table. We touched on many topics that afternoon: the Bauhaus and Black Mountain, Josef Albers, John Cage. I came to realize, as we spoke, that Karnes belonged to a fast-disappearing generation of artists who had lived through an amazing flowering of American art and culture. During that period, she had been both a witness and a participant. Her gnarled and sensitive hands had handled clay for sixty years, and clay had taken her on some unexpected journeys. Through an odd set of circumstances, some planned and some unforeseen, Karnes had become—and still remained, in my sense of her—the quintessential potter of Black Mountain.

2.

Karen Karnes has lived her life primarily as a solitary studio potter, recognizing no school or tradition but her own and fiercely guarding her privacy. Anyone who makes the pilgrimage to her Vermont studio can gauge the distance she currently maintains from what Thoreau disdainfully called civilized life. And yet throughout her life, Karnes has enthusiastically taken part in various social, artistic, and educational communities. There is something deep in the American grain in the idea of cultivating individuality through community.

American utopian endeavor during the first half of the nineteenth century produced two contrasting experiments, both based on Emerson’s notion of self-reliance, and both are relevant to Karnes’s career. One was Thoreau’s experiment in solitude at Walden Pond, in which he sought, as he put it, “to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life.” The other was Brook Farm, outside of Boston, in which Hawthorne, Margaret Fuller, and Bronson Alcott took part. Meaningful work was at the heart of both visions. “We sought our profit by mutual aid,” Hawthorne wrote, “instead of wresting it by the strong hand from an enemy, or filching it craftily from those less shrewd than ourselves.”

Karnes’s engagement with work-based experimental communities like Black Mountain was established almost from her birth in New York City in 1925. Her parents were Jewish garment workers from Russia and Poland. During her early childhood, the family lived in the Bronx in what Karnes describes as a cooperative colony for families of “really working-class people.” It was, she says, a social experiment both architecturally, in the design of houses, and culturally, with its own library, art classes, and Yiddish-language school. Politically, it was “very, very left-wing,” she says, with the utopian conviction conveyed to the children, who were given a great deal of freedom, that this was “the way the world was going to be or should be.”

After attending the High School of Music and Art, Karnes entered Brooklyn College, where she found in the architect and painter Serge Chermayeff a mentor for life. The Chechen-born Chermayeff had trained in England, where he had developed a strong interest in the relation between architecture and community. At Brooklyn College, he taught a course in design based on the methods of the Bauhaus. It was at Chermayeff’s instigation that Karnes spent the summer of 1947 at Black Mountain College, taking a course with Josef Albers. “I was a good student,” Karnes told me of her summer at Black Mountain with Albers. “He was hard clay, not soft clay.” She made a gesture with her hands like an ax coming down.

At this point, Karnes had not yet discovered clay; what she had encountered was an emerging connection between making art and forging community. She fell in love with a fellow student at Brooklyn College, David Weinrib, whom she married in 1949. When she first moved in with Weinrib, he was designing lamps for a factory in Pennsylvania called Design Technics. It was in this industrial context that Karnes was first introduced to clay. Weinrib brought home “a great lump of clay” for Karnes to work with on the deck of their rented house. Karnes found that she had a talent for designing lamp bases for mass production.

After a year and a half at Design Technics, Karnes and Weinrib traveled to Italy, where they again found themselves in an industrial environment. They had a friend who had worked in a town near Florence at a ceramics plant there. “He told us if we go there,” Karnes recalls, “we can just work at the factory, so that’s what kind of inspired us where to go.” Weinrib, who suffered from asthma, had conceived of the Italian sojourn as a way to escape the silica dust and glaze fumes of pottery while at the same time acquiring the classical art training that he had missed at Brooklyn College. (He speaks of the irony of drawing from the nude in Florence at the very moment when, back in New York, Franz Kline and Willem de Kooning were reinventing painting.)

But it was in the industrial town of Sesto Fiorentino that Karnes discovered her vocation. She saw students at the factory learning to throw pots at the wheel. “I left very quickly,” she says, “and made a wheel in my own house and put it there.” She found she had a natural talent at the wheel, and the people at the factory were happy to fire the pots she brought to the kiln on the back of her motorbike. After their return to the United States, the Weinribs moved to Alfred University, which had the premier ceramics program in the country. It was at Alfred that they received the unexpected invitation to come to Black Mountain College.

3.

Despite its ready availability in the riverbeds of western North Carolina, clay had a tenuous existence at Black Mountain. Josef Albers based much of his teaching on the juxtaposition of materials, but he didn’t consider clay a suitable material for students to work with. He thought that clay was too malleable, too yielding, too acquiescent to the students’ whims and desires. In Anni Albers’s phrase, clay didn’t offer enough of the “veto of the material.” There is something puritanical about this response to clay, as though it shared some of the characteristics of a loose woman. La donna è mobile. But there was a second reason for Albers’s dislike. He associated clay with the American craft tradition—“ashtray art,” as he disdainfully called it—which he considered a form of recreation or therapy rather than a serious undertaking in artistic experience. (He may also have distrusted the emphasis on folk traditions, which may have recalled for him one unsavory aspect of Nazi ideology.)

It was the poet Charles Olson who brought clay to Black Mountain. Olson, whom Albers had hired to teach literature, took over the leadership of the college in 1949, after the Alberses’ departure. Trained at Harvard in American literature, Olson, a giant of a man who was too tall for military service, had written propaganda for the Office of War Information (later folded into the CIA) from 1942 until 1944. He had developed a close friendship with the poet Ezra Pound, imprisoned at St. Elizabeth’s Mental Hospital after the war for contributing anti-Semitic propaganda to the Fascist regime in Italy.

Like Pound, Olson was passionately interested in the gestural glyphs and written characters of non-Western cultures. In his landmark manifesto of 1950, “Projective Verse,” he had laid out a program for a more immediate poetic language, in an effort to restore it to the physical “push” of breath and voice. During the winter and spring of 1951, Olson traveled to the Yucatán peninsula in Mexico, sending lengthy letters to the poet Robert Creeley, back at Black Mountain, eventually published as Mayan Letters. The title was a pun, referring both to the correspondence and to the Mayan hieroglyphs that Olson, believing a poet might succeed where scholars had failed, hoped to decipher.

Olson’s Mayan Letters are hot with the excitement of a man who is on to something. He contrasted the vital “density” of Mayan writing, in which concrete objects are pictured in inscribed signs, with the abstract and moribund “sieve” that phonetic words had become in English. From the window of a third-class bus on a bad coastal road, he glimpsed a promising site for digging; “christamiexcited,” he wrote Creeley, in a sort of English-language glyph. He returned from his excavation “with bags of sherds & little heads & feet—all lovely things.”

4.

Most strikingly, however, Olson aligned poetry with traditional crafts in “Projective Verse,” calling for “the attempt to get back to word as handle.” Crafts were central to Olson’s emerging vision of what he called the “second heave” of Black Mountain College, after the Alberses’ departure. The key to maintaining momentum, in Olson’s view, was his “institute model,” an array of concentrated studies of which the first would be devoted to crafts. And for Olson, the quintessential craft was pottery.

By late 1951, Olson was determined to identify a significant potter who might be persuaded to teach at the college. In his search, Olson consulted Bernard Leach, author of the influential A Potter’s Book (1940), the Bauhaus-trained émigré potter Marguerite Wildenhain, and Charles Harder, who ran the ceramics program at Alfred University. By March 1952, Olson felt he knew enough to offer a permanent position to Wildenhain. He explained that he had “taken on this potter post as a sort of personal gauge, why, I can’t say, except that it damn well interests me as an act (pots do).” He added that pottery was “tied up severely with my own sense of what is now the push in the old-fashioned arts.” Wildenhain was committed to the pottery she was establishing in Northern California, and Leach’s candidate, his pupil Warren MacKenzie, was determined to study in Japan.

Leach then informed Olson that he himself was planning a tour of the United States. He would be traveling with his protégé, the young Japanese potter Shoˉji Hamada, and with Soˉetsu Yanagi, a philosopher steeped in Whitman and William Blake and the leader of the Japanese folk-art movement known as Mingei (“art of the people”). Olson and Leach agreed on a ten-day residency at Black Mountain, combining lectures and pottery demonstrations, to be held in October 1952. Wildenhain agreed to serve as the master of ceremonies for the occasion.

Olson wanted the college to have a head start in pottery for the summer session. Harder wrote to recommend Weinrib and Karnes, specifying that Karnes, who had studied under Harder, “has a placid and calm disposition and a most attractive personality. She can be depended upon to keep the team on a practical course and to get the job done.” While Harder suggested the Weinribs as possible candidates for a more permanent position at the college, Olson initially offered them the job for the summer only, to share a position as potters-in-residence.

Fortunately, they didn’t have to start from scratch. Paul Williams, the resident architect at Black Mountain, had built the Pot Shop in the meadow at the Lake Eden campus, to the potter Robert Turner’s specifications. The son of Quakers, Turner had been a conscientious objector during World War II, working with developmentally disabled students. He had taught at Black Mountain from 1949 to 1951, but finding little support for his endeavors, he had returned to Alfred. It was in Turner’s studio, somewhat removed from the main operations of the school, that Karnes and Weinrib set up shop and prepared for the arrival of the distinguished visitors.

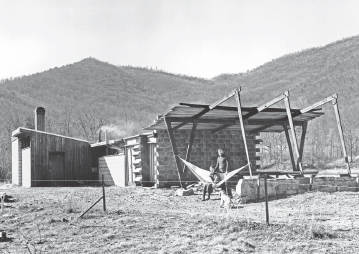

Karnes and Weinrib at the Pot Shop at Black Mountain College

Call it the epiphany on Black Mountain: Three wise men from the East come to the mountaintop to share the good news. On the morning of October 20, 1952, the white-mustached Bernard Leach, born in Hong Kong and steeped in the wisdom of the East (or at least in the pseudo-Asian wisdom of Edwin Arnold and Lafcadio Hearn), gave a lecture, “America: Between East and West.” One might think that America would benefit from its geographical centrality, but Leach saw little hope for American craft. What he meant by East and West was really Japanese Mingei and his own pottery at St. Ives, in England, two attempts at a revival of native pottery practices.

Leach’s travels in the United States, he wrote, confirmed his “thankfulness” to have been “born in an old culture.”

For the first time I realized how much unconscious support it still gives to the modern craftsman. The sap still flows from a tap root deep in the soil of the past, giving the sense of form, pattern and color below the level of intellectualization. Americans have the disadvantage of having many roots, but no tap-root, which is almost the equivalent of no root at all. Hence Americans follow many undigested fashions.

Leach’s snobbishness extended to North Carolina clay, which he found insufficiently plastic for his needs. Hamada, by contrast, embraced the local clay, welcoming its limitations as additional challenges. It is characteristic of Karnes’s independence that what she took from Hamada was an attitude, an ethic. She had no desire to be a Japanese potter. And the big ideas that Yanagi and Leach were selling—the “unknown craftsman,” the subsuming of individuality within an old tradition, the avoidance of self-expression, and so on—were already familiar to Karnes through more American channels, namely, her friends John Cage and Merce Cunningham and her teacher Josef Albers. All were, in one way or another, exponents of the impersonal in art.

6.

Karnes witnessed the famous occasion during the summer of 1952 when Cage organized a group performance in the dining hall. He had been reading Zen Buddhist texts along with writings of the medieval German mystic Meister Eckhart. Eckhart wrote that “we are made perfect by what happens to us rather than by what we do,” and Cage had begun to envision works of art that were based on chance, on serendipity, on letting things happen. He invited Black Mountain students and teachers to see what happened if they were each assigned an activity and a period of time in which to do it.

Merce Cunningham danced with a dog, Cage stood on a ladder and recited lines from Meister Eckhart, Rauschenberg exhibited his White Paintings, someone played a radio while someone else projected movies upside down on the wall—all to the accompaniment of scratchy Edith Piaf recordings played at double speed. This first “happening” ended with coffee served in cups that had been used as ashtrays during the performance. Soon after he left the campus, inspired by Rauschenberg’s paintings of nothing and by Eckhart’s injunction to cultivate a mood of silent expectation, Cage composed his epochal “silent piece,” titled 4′33″, in which a pianist sits at the piano for four minutes and thirty-three seconds without playing a note.

There was another happening the following summer, when the Weinribs invited three American potters to Black Mountain—Peter Voulkos, Daniel Rhodes, and Warren MacKenzie—all of whom were destined for big careers in American pottery. This time, the performance was organized by David Weinrib and centered on Lake Eden at night. M. C. Richards set the mood by reading from a grandiloquent poem that she had written in the style of Milton. Daniel Rhodes describes what happened next:

At the climax of the poem, a boat appeared on the lake. We were all sitting in the dining room, and a boat appeared out of the darkness and a searchlight shining on it, and in the prow of the boat was Karen Weinrib in the nude draped with vines and flowers.

As the school’s finances and student body shrank during the early 1950s, the architect Paul Williams was interested in building a new artists’ community, and he shared his plans with M. C. Richards and John Cage. Richards, who taught literature at Black Mountain, had begun studying pottery, first with Turner and then with Karnes. Her book Centering: In Pottery, Poetry, and the Person remains one of the classic works on the nature of pottery. Richards wanted pottery to be central to Williams’s plan. Karnes and Weinrib were invited to join Richards, Cage, the musician David Tudor, and Paul and Vera Williams at the Gate Hill Cooperative at Stony Point in upstate New York. “The pot shop was the first place built,” Karnes remembered, and again it was set off (at Karnes’s insistence) from the rest of the community.

What did living with Weinrib, Cage, and other avant-garde experimentalists mean to Karen Karnes as an artist, at a time when American art was undergoing radical change, with the rise of minimalism, performance art, and—Cage’s special contribution—the embrace of chance? An anecdote from John Cage gives a sense of the distinctive mood of the place.

“When I first moved to the country,” Cage wrote in 1958, “David Tudor, M. C. Richards, the Weinribs, and I all lived in the same small farmhouse. In order to get some privacy I started taking walks in the woods. It was August. I began collecting the mushrooms which were growing more or less everywhere.” Cage served a meal of what he assumed to be skunk cabbage, which is edible, to six people at Gate Hill, including a visitor from the Museum of Modern Art. The results were predictable.

After coffee, poker was proposed. I began winning heavily. M. C. Richards left the table. After a while she came back and whispered in my ear, “Do you feel all right?” I said, “No. I don’t. My throat is burning and I can hardly breathe.”

Soon it was clear that he needed to be taken to a hospital. Cage, who barely survived the ordeal, later learned to distinguish skunk cabbage from hellebore, which is poisonous.

The tale of the poisonous vegetable is one of the vignettes in Cage’s collection of minute-long stories titled Indeterminacy. It follows his famous account of studying with Schoenberg. Schoenberg warned that Cage’s lack of feeling for harmony would be “like a wall I could not pass.” “In that case,” Cage replied, “I will devote my life to beating my head against that wall.” The adjacency of the stories invites a closer interpretation of the mushrooms, which he decided to continue collecting despite the hellebore mistake. Without reading too much into it, one can see certain themes: the place of risk in the artistic life (mushrooms, poker), the Walden-like retreat to the woods and the balancing proximity of the art world (the unnamed visitor from MoMA, presumably there to see Weinrib), and the nearness of death.

Karnes and Weinrib divorced in 1959, at a time when Weinrib had moved away from clay. He became a sculptor in unorthodox and colorful materials like resin and fiberglass. At the same time, his interest in performance art and happenings intensified. In 1960, the year after he left Stony Point, he became part of a small circle of artist friends in New York City that included Eva Hesse. Vacationing in Woodstock in 1962, Weinrib, Hesse, and their friends performed as the Ergo Suits Traveling Group, using colored sculptures as bizarre costumes.

Karnes’s commitment to clay deepened during the 1960s. Her emerging aesthetic attitude seems to have found confirmation in the self-effacing gestures of Cage and Merce Cunningham rather than Weinrib’s more expressive mode. And yet Weinrib’s openness to sensual materials and to bright color, even to a theatrical aspect of pottery, might have revealed a set of possibilities that could only be fully explored later, during the period when Karnes had forged an enduring relationship with a new partner, the potter and Sufi practitioner Ann Stannard.

8.

During their years at Black Mountain, Karnes and Weinrib had visited Jugtown, the folk pottery in central North Carolina. Neither Karnes nor Weinrib had much use for American folk pottery, however, including the rich traditions of North Carolina clay. But while Weinrib deliberately banished craftlike elements from his ceramics in his attempt to raise ceramic art to the level of sculpture, Karnes pursued a more internal quest. She followed the inner logic of the pots she was making, allowing basic elements to take on new forms and meanings.

Karen Karnes, Jar, 1969

Self-expression enters Karnes’s art obliquely, through the handle and the lid. Garth Clark has written of the “single moment of visual theater” in Karnes’s casseroles that “the handle on the lid is made from a twisted ribbon of pulled clay.” Ten years after she began making casseroles, she encountered salt glazing for the first time during a sojourn at the crafts community of Penland, in the mountains of North Carolina near Asheville, in 1967. The result was the extraordinary flourishing of stoneware jars with faceted lids that remain among her best-known forms.

How do pots like these come to matter to us and find a way into our lives? A passage from T. S. Eliot’s play The Confidential Clerk suggests a possible answer. The financier Sir Claude regrets having given up a career as a potter and the pleasure of handling clay. Then he reflects on what pots grant access to: not primarily “use,” he decides, nor “decoration” but rather an elusive quality he calls “escape into living.”

9.

Karnes’s late work, after her departure from Gate Hill in 1979, carries the feeling of such an “escape into living.” These late pots have their own internal development. Karnes makes a series in one direction, exhausts its possibilities, and never looks back. The catastrophic fire in May 1998 that destroyed her studio and the house she shared with Stannard turned out to be not so much an ending as yet another escape into living. The thin, cylindrical pots displayed in groups of two or three look as if they have survived something—as indeed they have. They speak of transience and evanescence, of that continual metamorphosis that is at the heart of the potter’s craft.

In their evocation of permanence and change, Karnes’s assemblages remind me of an extraordinary passage in Willa Cather’s novel The Song of the Lark. The opera singer Thea Kronborg has traveled to the Southwest and visits a site of Indian cliff dwellings, where there are many relics of masonry and pottery. Thea listens to an old German immigrant who has learned a great deal about Pueblo pottery and explains the intimate connection between domestic masonry and pottery:

After they had made houses for themselves, the next thing was to house the precious water… Their pottery was their most direct appeal to water, the envelope and sheath of the precious element itself. The strongest Indian need was expressed in those graceful jars, fashioned slowly by hand, without the aid of a wheel.

Later Thea bathes herself in a pool behind a screen of cottonwoods and has a sudden epiphany about the sources of art:

The stream and the broken pottery: what was any art but an effort to make a sheath, a mould in which to imprison for a moment the shining, elusive element which is life itself—life hurrying past us and running away, too strong to stop, too sweet to lose?

Cather is trying to say something here that is perhaps ultimately inexpressible, something about how art can give us eternal moments—still moments—stolen from the flux of life that make it all seem worthwhile.

10.

As Mark Shapiro and I were getting ready to leave Morgan, after a tour of Karnes’s big kiln and her small array of selected pots on display, she presented me with one of her new pots, a strange, zigzagging cylinder vase I had been admiring. The vase was pebbled with brown salt glaze on one side and a wonderful purplish hue on the other, where the wood fire had rushed through the cross-draft kiln. The base was like a funnel or a miniature space shuttle. The heavy rim seemed more cut than rounded, like an agate geode that had been cut flat and polished.

I cradled the vase on my lap as we drove down through the red pines of central Vermont, with intermittent glimpses of the Connecticut River pockmarked with ice. I had a dawning sense that Black Mountain was something more than a school with a brief lifespan, that it still lived—Albers’s “hard clay” and Cage’s mushrooming imagination—in this quiet dignified woman of my parents’ generation and in the dignified pots she made.

11.

David Weinrib lives with his wife, Jo Ann, in an art-filled apartment that doubles as his studio in the Chelsea neighborhood of Manhattan, a few blocks from the Hudson River. Before I drove down to New York to meet him, I had seen only photographs of Weinrib from the 1950s, when he was bearded and youthful with a full head of hair. His imposing bald head strikes the visitor today, along with his beaklike nose, piercing eyes, and quick, ironic smile. Jo Ann had made coffee and laid out a ceramic slab plate—“some potter in Florida,” David murmured—with apricots, nuts, and grapes. Mark Shapiro, with whom I was again traveling, was taping our conversation for use in a retrospective of Karen Karnes’s work that he was organizing. While Weinrib was happy to talk about Karnes, he was quick to point out that one of the best-known photographs of Karnes at Black Mountain, sitting demurely on a stone wall by the Pot Shop, is actually half a photograph, with Weinrib’s image cropped away.

Weinrib was wearing a white shirt, a white fleece vest, and tinted aviator glasses; he was comfortable in the kitchen, energetic, gesturing freely, and ready to go at it. I was eager to talk about Black Mountain, which Weinrib described as “a northern college in the South.” He said there was “an atmosphere about Black Mountain that just stimulated creativity and ambition.” I asked him if his work had changed there, and he said that it had, decisively. He left the pottery wheel behind and made his first slab pots at Black Mountain. The idea, he said, was to “change the idea of pottery,” to move it in the direction of sculpture.

We kept talking as we wandered through the apartment, stopping to look at objects and photographs. The apartment immediately felt familiar to me. It reminded me of my mother’s studio spaces when I was growing up, with the accumulation of many years’ work, various bits and pieces of inspiring bric-a-brac pinned to the walls, and art books balanced on the windowsills. Something about the rooms, especially the rough-hewn wooden stairs leading up to the sleeping loft, reminded me of Japan, where Weinrib had spent a lot of time and where he and Jo Anne had first lived together. She showed me a photograph of her in a kimono, or rather, as David said, “slipping out of it.”

I was particularly struck by a pot that Weinrib and Karnes had made in collaboration. It was structured like two principles in dialogue, a rounded form that Karnes had thrown on the wheel and a rectangular form that Weinrib had formed in a mould. I found myself thinking that their marriage must have felt like this at its best; at its worst, I speculated, like two different temperaments coming into collision, a square peg and a round hole. While Weinrib expressed admiration for Karnes as a potter, a “natural” at the wheel with a terrific sense of design, he also hinted that he was more of a free spirit, more of a Sixties temperament. He spoke with distaste of the uptight European émigrés at Black Mountain and the transgressive pleasure of persuading Karnes to appear nude in the pageant on the lake.

Collaborative pot by Karnes and Weinrib

Weinrib and Karnes had struck me from the start as an unlikely pair, and eventually the contrasts must have become too stark. But the failure of their marriage seemed less interesting than the fact of it, during those years at Black Mountain and right after. The particular temperamental divide at the heart of their marriage (to the degree that a stranger can discern such a thing) seemed, in some tantalizing way, to represent the divide at the heart of Black Mountain. No one has been able to explain the sheer number of artists and writers and other creative people whose lives were decisively touched by the creative ferment of Black Mountain. Perhaps it had something to do with the confluence of European refugees and American mavericks in search of safe harbor, finding unexpected common ground in the Appalachian outback.

But as I drove back to Massachusetts with Mark Shapiro after an afternoon with the Weinribs, I felt that this divide at the heart of Black Mountain might have been more specific, something on the order of Nietzsche’s division of the artistic impulse into Apollonian and Dionysian tendencies. On one side was everything that Josef and Anni Albers represented: the quiet, orderly, self-effacing, conscious, and clean-edged exploration of the nature of materials and the principles of design. One could see some of this same spirit in Merce Cunningham’s experiments with pure movement, Rauschenberg’s White Paintings, or in John Cage’s systematically self-erasing explorations of random sounds and silence.

There was a countervailing spirit at Black Mountain, however, and David Weinrib was the perfect embodiment of it. That spirit was anarchic, chaotic, performative, self-expressive. One could see it in Charles Olson’s ecstatic outpourings of words and ideas, his epic and exuberant Maximus poems, which seemed the antithesis of Josef Albers’s minimalist forays into poetry. One could see it in the action painters at Black Mountain like Franz Kline and Jack Tworkov.

I realized that Black Mountain College, for the twenty-four years of its existence, had drawn its energies from the tensions of this divide. What is remarkable, in retrospect, is not how quickly the experiment died but rather how long it held together for so many vibrant people.