1.

I had stumbled across pieces of an amazing story over the years, an epic errand into the wilderness that seemed only partly believable, more like a dream than a historical event. The germ of the story was this. The English potter and entrepreneur Josiah Wedgwood, who had built a pottery empire in his native Staffordshire, had sent one of his agents on a dangerous adventure across the Atlantic and into the wildest regions of the Carolina outback, where there were many ways to die. The object of his quest was a glistening white clay, a clay as white as snow. With the right kind of clay, potters in England could make porcelain, the elusive “white gold” of the alchemists, and solve the secret so closely held by Chinese potters for centuries.

The journey in search of white clay had occurred during the months leading up to the American Revolution, when the Carolinas were riven by violent disputes over land, and the keepers of the clay were the proud but increasingly embattled Cherokee people. Wedgwood’s agent, an adventurer named Thomas Griffiths, risked shipwreck, murderous thieves, vengeful Indians, and the encroaching winter in the high mountains. But mere survival was not enough. He had agreed to return to England only after securing five tons of white clay.

It seemed like a fairy tale, one of those impossible quests imposed on the third of three sons, who wins the king’s daughter if he succeeds but dies if he fails. As I assembled the fragments of the story, I found that the search for Cherokee clay was much richer, braided with more strands, than I had originally imagined. I had pictured a single traveler, but I soon discovered that there had been three successive journeys to the Cherokee towns by three different travelers. One of these journeys involved a distant relative of mine, the Quaker explorer, naturalist, and artist William Bartram. Bartram’s account of his own travels inspired, in turn, several key details in Coleridge’s opium dream of a poem, “Kubla Khan.” Actually, there was a fourth traveler in the mix, because I myself, another third son, was determined to find and see with my own eyes the source of the snow-white clay.

2.

The sun was already descending toward the Great Smoky Mountains when my friend Roy Nydorf and I finally reached the outskirts of Franklin, North Carolina. There wasn’t much daylight left to look for Cherokee clay. We had left Roy’s stately old farmhouse outside Greensboro early that morning, estimating that it would take us four or five hours driving west on Interstate 40 to reach the mountains. But we had taken a long detour through the Cherokee towns west of Asheville. We had a place near Franklin to spend the night, at my friend Bill Quillian’s retreat on Scaly Mountain, above the resort town of Highlands near the Georgia border, so we could afford a leisurely pace. Besides, it was a bright, sunny day in late July, with a gentle breeze, and the landscape opened like a Japanese fan along the highway.

We passed a chain gang on the outskirts of Asheville; African American inmates in orange suits collected trash by the highway, while two state police officers armed with shotguns kept an eye on them. We were getting hungry as the mountains came into view, and we passed an apple orchard, closed, according to a big, apple-red round sign, until August 1. Roy told me to stop the car. He climbed the chain-link fence, grabbed a handful of apples, and was back in a couple of minutes. I was thinking of the chain gang. The apples were hard and sour.

Roy knew a nice place to get some grilled trout and a glass of white wine in Sylva, an old town of wood and brick nestled in the hills. When we placed our lunch order, the waitress explained that they only served trout for dinner. We looked so crestfallen that the cook, a dark-haired young Cherokee, called out from the open kitchen that he would cook us some trout anyway, and a wonder it was, perfectly grilled and served on a bed of lettuce with a wedge of lemon. Sylva could have served as the setting for a movie Western, with a drop-dead-beautiful white courthouse notched on a hillside over Main Street. Poking around an antiques store after lunch, we found an old still, not for sale, with long pipes of burnished copper. The shopkeeper had worked for the DA’s office for many years, and he had come across a lot of illegal moonshine machinery, but this, he assured us, was the finest still he had ever seen.

Then, with a map spread out on the dashboard, we headed for the town of Cherokee, straddling a cleft in the mountains, where the Indian casino faces the luxury hotel and a fast river rushes over rocks between them. Roy wanted to show me two paintings that Shawn Ross, a native Cherokee who had studied art with Roy at Guilford College, had painted and the hotel had bought for display. We walked into the casino and Roy asked the hefty, uniformed security guard blocking the way where the cultural center was. “Culture,” he said, gesturing toward the single-minded clients hunched over slot machines. “This here is the culture.” He liked the joke so much, he said it again. “Ain’t no other culture but this in Cherokee.”

Shawn’s painting of a “Booger Dance,” hanging in the sterile hallway of the luxury hotel, suggested another culture altogether. Masked dancers disguised as bears and badgers, representing alien forces among the Cherokee people, loomed from the firelit shadows. The intensity of the scene reminded me of Caravaggio, and Roy told me that Shawn had spent a semester studying art in Italy before coming back to Cherokee. From the hotel, we drove to the Cherokee Artists’ Collective nearby, where there was a little museum installation. I studied the pottery case for a moment, where there was an explanation of the two methods traditional Cherokee potters use to make vessels: by coiling and by the ball method (taking a ball of clay and hollowing it out with your fingers). The Cherokee pots were unglazed, and their only surface decoration was caused by smoke blackening the surface during low-temperature firing.

Suddenly I recognized one of the pieces in the case. The central pot on display was my pot. Or rather, it was exactly the same as the pot that my parents had bought right there in Cherokee, in the Cherokee Artists’ Collective, when they were honeymooning in the Smoky Mountains in 1949. The pot was about six inches tall and the same width, with two handles added on each side and circular medallions under each handle that were meant to look like metal rings. Half the pot was blackened by smoke; the other was the gentle persimmon orange of Cherokee pottery. The pot looked burnished, carved, and rubbed. Above the pot was a picture of the potter and her name: Maude Welch.

When I got back to my house in Massachusetts, where the pot sits on my writing desk, I immediately checked the bottom, where I found the inscription: “Made by Maude Welch / Cherokee, NC 8-6-48.” I also found an old postcard photograph online

of Maude Welch burnishing the clay surface of a pot just like mine.

3.

Roy and I had spoken many times about heading for the mountains to look for the fine white clay in Cherokee country, and he had become as obsessed as I was about finding it, whatever it took. I wasn’t at all surprised. Roy is a wry and tenacious artist, originally from Long Island, who teaches studio art at Guilford College. An expert printmaker and carver, he was my mother’s last art teacher, when she returned in her sixties to the studio, and he also taught some of my friends when I was a student there. Roy spends a lot of time outdoors; he knows the woodland trails around Greensboro; he can show you, down in the Guilford woods where Levi Coffin hid escaped slaves, the biggest poplar tree in North Carolina. He knows which fields are sown with arrowheads, and he has a passionate feel for the specific shapes and colors of the natural world: snakeskin, kelp, antlers, flint.

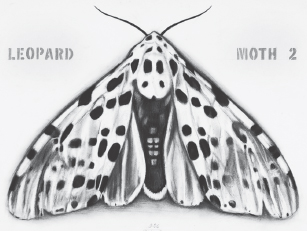

Roy Nydorf, Leopard Moth 2, 2006

While I was waiting for Roy to grab his bags for the long drive west, I had admired the new work on the walls of his living room. Several of the pictures were large-scale pastels of moths, with the species identified in hand-printed letters below the image. Roy had chosen the perfect medium for these great-winged creatures. The soft pastel exactly mimicked the powdery feel of a moth’s wing.

Roy was at Yale getting his MFA just after Josef Albers had stopped teaching there. One of Roy’s teachers, the still-life master William Bailey, liked to imitate Albers’s ways in the classroom. “Boy!” Albers would say, before handing down some gruff opinion. As Roy and I drove on toward Franklin and the Smoky Mountains, I told him about how Albers liked to find loops and numbers hidden in aerial views of the mountains, which were just coming into view.

As a child growing up in Indiana, I had a cat called Smoky, half Siamese and black as the night. When I first heard of the Smoky Mountains, as the romantic place where my parents had spent their honeymoon, I thought they must be black as smoke. But it is the white and grayish wreaths of cloud that give these mountains their name, like smoke signals draped across the pines of the mountain heights.

4.

The only notion I had of where to find the beds of Cherokee clay came from a decade-old online article by an Australian geologist who had never been to North Carolina. The spotty directions seemed more like a map for buried treasure than reliable information. We found route 28 heading north from Franklin, as instructed, and took a left at the next traffic light. But there was no bridge over Iotla Creek from which we could count back one sixth of a mile, per our directions, then ask for Boyd Jones, and find the clay beds. A couple was carrying a pie along the side of the road, so I gave it a try. “It’s pronounced ‘Iola,’” the man said pedantically. “The ‘t’ is silent.” I told him we were looking for white clay. “Clay as in C-L-A-Y?” he asked. No, as in K-L-E-E, I almost answered.

Then in the distance, alone and walking right down the middle of the road, an old-timer in overalls made his slow way. Through the opened window I told him our errand. “Used to be a mine down around Rose Creek,” he said, “where they dug white clay.” He spat a splat of brown tobacco spit onto the hot asphalt and it almost sizzled on the tar. “They say some English fellers dug up some of that clay a long time ago and took it all the way back to England by ship.” Yes, I said, yes, that’s the clay. Where could we find it? “Go around the mountain and turn by the bridge to Rose Creek and it’s right there, where the bait store is at.” How far? “Round about three miles.”

These directions turned out to be not much better than the previous ones. What exactly was the mountain we were going around, and why was there no indication of Rose Creek? We got back to Highway 28 no wiser and stopped for the second time at the gas station where I’d asked for directions to Iotla Creek two hours earlier. This time, I helplessly asked for directions to Rose Creek. “It’s right up there,” said the girl at the cash register, pointing up the highway, “before that bridge. Just take a left on Bennett Road and it’s right there.” It was. The bait store turned out to be an ambitious operation called Great Smoky Mountain Fish Camp & Safaris. Snug by the side of the Little Tennessee River, a large wooden building was flanked by racks of canoes and kayaks. Down by the river there were a couple of campsites and a viewing platform with a barbecue pit made of stone. A woman and two kids were roasting marshmallows when we arrived. She said the guy who ran the place would be back in a few minutes. We walked toward the wooded ridge above the camp and what we saw took our breath away. Down below was a vast crater of red earth with standing water a few feet deep. A great blue heron picked its way along the edge of the pool while a hummingbird worked the flowers of some underbrush.

All around us was evidence of a vast landscaping project. It was the sheer scale of the operation that took us by surprise. Leading up to the ridge was a spiraling road of red clay, newly bulldozed. Sheets of mica six inches wide were strewn about on the road, like broken glass after an accident. But what really caught our attention were clumps of white clay, smooth to the touch, which disintegrated between our fingers like talcum powder. Cherokee clay! We could see veins of the stuff in the granite bluffs over the river, but to get closer to them we had to descend around the heron’s pool and walk along another new roadbed alongside the river. Huge blocks of white quartz placed every ten yards lined the road, like some Roman triumphal way. “Whoever did this had a vision,” Roy remarked.

A truck pulled into the driveway, and there was Jerry Anselmo, owner and outfitter of the Great Smoky Mountain Fish Camp & Safari. Jerry was friendly from the start and encouraged us to take plastic bags out to the bluffs to collect as much white clay as we wanted. Some geologists had stopped by from time to time, he told us, but his interest quickened when I mentioned the English potters of the eighteenth century and the Cherokee. “I own Chief Cowhee’s village, too,” he said, “down in the valley. I’ve found buckets of Cherokee pottery down there.”

Jerry invited us up to his living quarters above the store, and we got a clearer sense of him. He was originally from Mandeville, Louisiana, across Lake Pontchartrain from New Orleans. He’d come to the Smoky Mountains sixteen years earlier. “Then I got kidney cancer,” he said, “and that gave me a new view on what life is for.” He became interested in Cherokee religion, reading all he could about their life in this river-riven landscape. As we sipped long-necked bottles of beer at Jerry’s bar, he dragged out a bucket of Cherokee pottery shards. They were brown or gray, unglazed; whatever color they retained had come from the smoke of the kiln. Each carried a pattern of some kind, scored with a pointed tool: zigzags in parallel or an array of tight spirals, like Van Gogh’s Starry Night. I was fingering one gray fragment in my hand like a magical talisman. “Take it,” Jerry said. “No one will ever care for it more than you do.”

Later, when I was back in Greensboro, I tracked down a photograph of Jerry Anselmo’s mine as it looked around 1915. The mine itself is down below, in the center of the photograph. The second building, above it, is probably where they packed the kaolin for removal. To the left, a horse or mule pokes its head about the great snowdrift of white clay. I love the gaunt trees like stubble on the horizon, and the drama of the sunlit clouds like more kaolin drifting in the sky. How redolent of the hardscrabble South the postcard is! And I sensed some match between this

ambitious mining operation and Jerry Anselmo’s visionary landscaping project.

All that exposed red and white dirt made me think of an archaeological dig. It made it easier to summon the waves of people who had taken an interest in these clay beds. With his bucket of pottery shards and his five fish weirs across the Little Tennessee River, some of them built by the vanished Cherokee themselves, Jerry Anselmo was trying to summon the Cherokee ghosts from his land, hoping their spirits could help him find a way through his life. Roy and I were curious about the mining operation that flourished there well into the twentieth century. But most of all, we were looking for traces of earlier travelers, those “English fellers” who, as the old-timer said, “dug up some of that clay a long time ago and took it all the way back to England by ship.”

5.

Three adventurous travelers had come this way during the eighteenth century, through some of the most dangerous and unsettled backcountry in the American colonies. One was a potter; one was the agent of a potter; and one, the most remarkable of all, was a writer, artist, and explorer. Two were Philadelphia Quakers. The lure of white clay brought the potters, just as it had brought Roy and me. The aim was to make something beautiful with that white clay, to turn raw material into art. So profound was the draw of the clay that these men were willing to travel thousands of miles, across oceans and mountains, to bring it back home.

The story begins with a young potter named Andrew Duché, a Philadelphia Quaker of Huguenot descent who was born around 1709. Andrew’s father, Anthony Duché, was among the first potters in the American colonies to make stoneware pottery. He glazed his jars and jugs with salt thrown into the kiln, and was apparently the first to do so in Philadelphia. Andrew, his third son, joined other ambitious Quakers in their exodus to the South. He may have heard rumors that kaolin, the pure white clay used in porcelain production, was abundantly available in the Savannah River area. With his wife, Mary, he moved to Charleston, South Carolina, during the early 1730s and started a pottery operation there, similar to his father’s in Philadelphia, making him the first potter to produce stoneware south of Virginia.

Duché’s announcement appeared in the South Carolina Gazette:

This is to give notice to all Gentlemen, Planters and others, that they may be supplied with Butter pots, milk-pans and all other sorts of Earthen ware of this Country made, by whole sale or retail, at much cheaper rate than can be imported into this Province from England or any other Place, by ANDREW DUCHE Potter… at his Pot-house on the Bay.

In Philadelphia, Duché had made stoneware in a heavy German or lighter English style, sometimes with decoration in cobalt blue. But in Charleston he joined a community of artists and patrons fascinated by all things Chinese, and delicate Chinese porcelain in particular. By 1737, Duché had moved to New Windsor, a new settlement on the Savannah River, where there were deposits of stoneware clay and a fine white clay known by its Chinese name of kaolin. It was there that, with Yankee ingenuity, along with the help of local Indians with whom he traded, he began experimenting with the arcane secrets of porcelain production. Archaeologists have found “several curious wheel-thrown bottles of unglazed white clay with Indian-style punctuated decoration” near New Windsor, and it is thought that these might be among Duché’s early attempts.

The following year, Duché’s friend Roger Lacy, the colony’s official agent to the Cherokee Indians, persuaded him to transfer his base of operations to Savannah. “His next aim is to do something very curious,” Col. William Stephens reported to the British financial backers of the newly founded Georgia colony in 1738. “He is making some trial of other kinds of fine clay; a small Teacup of which he shewd me, when held against the Light, was very near transparent.” A few months later, Duché claimed, a bit rashly, to be “the first man in Europe, Africa or America, that ever found the true material and manner of making porcelain or China ware.”

We can be reasonably certain that Duché had identified at least part of the secret. But other European potters had gotten there first. The most that he could claim was to be the first potter in the English-speaking world to have cracked the mystery of porcelain.

6.

Much to the frustration of potters in America and Europe, the secret of porcelain had been known to the Chinese for thousands of years. Sometime between the sixth and the tenth centuries, Chinese potters stumbled on two naturally occurring minerals: the fine, aluminum-rich white clay known as kaolin and another mineral rich in feldspar known as china stone. Thoroughly mixed and fired at an extremely high temperature, these materials fused into the extremely hard, glasslike, and translucent material we know as porcelain.

As with so many things about China, Western awareness of fine porcelain goes back to Marco Polo, that shadowy thirteenth-century adventurer who claimed to have spent seventeen years in the service of Kubilai Khan, the Mongol ruler of China. Among the marvels that Polo claimed to have seen abroad was a handmade porcellana, or “little pig,” as the delicate cowrie shell was then called. (The part of the sow that the shell’s opening was thought to resemble was the vulva.) On his return to Venice in 1295, Polo supposedly brought back a fragment of porcelain that still resides in the Treasury of St. Mark’s. The word china could easily have become the name for Chinese exotica like tea or silk; it ended up as the name for fine porcelain.

The well-guarded secret of Chinese porcelain eluded European potters until the eighteenth century. The man who really put china on the map, so to speak, was Augustus II (1670–1733), elector of Saxony and king of Poland, better known as Augustus the Strong. Augustus’s legendary strength in warfare supposedly gave him his nickname; other sources mention his prowess in bed (he reportedly fathered three hundred children). But what Augustus really loved, loved to the point of obsession, was porcelain. He collected many excellent specimens imported from China, and he once traded six hundred soldiers to the king of Prussia for 151 large Chinese blue and white vases. (That would be four soldiers per vase.) Augustus was determined to discover, at any cost, the secret of porcelain manufacture.

Augustus learned of a clever young alchemist named Johann Friedrich Böttger, locked him up in a laboratory, and impatiently awaited the results. Amid these Rumpelstiltskin-like conditions, Böttger first produced, in 1707, a remarkable red stoneware material, a high-fired clay that could be carved to resemble metal or polished to look like jasper. The inventive Böttger made a coffeepot with a dragon-mouth spout and a dragon-tail handle. But everyone knew that this discovery, however charming, was a stalling tactic.

The following year, the imprisoned alchemist evidently located a source of kaolin and succeeded in producing true porcelain, the lucrative “white gold” of Augustus’s dreams. Wasting no time, Augustus set up a porcelain factory in Meissen, on the outskirts of his capital city of Dresden, which continues to manufacture porcelain vessels and figurines to this day. Gradually other potteries in Vienna and France were able to achieve similar results, but reliable sources of kaolin were scarce. That is why English and American potters were willing to dig for it in faraway North Carolina.

A lingering mystery concerning Andrew Duché is why, given the rich deposits of kaolin nearby along the Savannah River, he went so far afield in search of more of the white clay. It may be that his experiments in making porcelain were not quite as successful as he claimed. During the summer of 1741, Duché showed William Stephens “a little Piece, in form of a Tea-Cup, with its Bottom broke out,” and Stephens expressed doubt about whether Duché’s pots really deserved the “Name of Porcelane.” Such uncertainty may have inspired Duché’s quest later that year for an even purer source of kaolin.

In any case, we know little about the precise circumstances of Andrew Duché’s journey in search of Cherokee clay during the fall of 1741. Duché was in touch with agents who traded with the Cherokee people and who served under the authority of General Oglethorpe, the head of the Georgia colony. These agents must have apprised him of the clay fields to the north and west. Miners in search of precious metals in the mountains would have confirmed the rumors. The frontier was still relatively peaceful; during the following decades, as tensions escalated between the American colonies and the English Crown, it would soon turn violent.

Duché made the journey himself, up to the banks of the Little Tennessee River and into the mountainous regions of North Carolina, to dig the valuable white clay. A German emigrant named John (or Johann) Martin Bolzius, a Lutheran minister for Austrian refugees in the orderly settlement of Ebenezer, Georgia, twenty-five miles up the Savannah River, made two entries in his diary concerning Duché’s visit “in search of mines” in October 1741.

Bolzius’s diary entries show that Duché, like Marco Polo, had a gift for verbally enhancing his discoveries:

With General Oglethorpe’s authorization he (Duché) has traveled amongst the Indians up in the mountains and has seen all sorts of singular things or else learned them from reliable persons. Amongst other things he recounted to me how amongst the Cherokees (a very populous nation, and amicable to England) where upon a cliff the footprints of an entire fleeing people, to wit, many men, women, and children, and all kinds of poultry, birds, and animals may clearly be seen. One also sees the imprint of a fallen man who is trying to rise by supporting himself on both hands; this can be seen because his posterior and his heel are imprinted on the rock as in sand… In the same region there are also some fire-spewing mountains, also a great cave in the cliff from which flows constantly a certain material which turns when it falls to the ground. There are many deep caves, just as in Canaan.

Duché was apparently describing fossils of various kinds, though his account is wonderfully suggestive, with its “imprinted” records of people and animals fleeing and falling. In addition to these marvels, Duché also mentioned a “marble quarry” that he had discovered, “from which he is taking along (to London) samples.” This marble, we can now conjecture, was actually kaolin, dug from the deposits near Franklin.

There were no live volcanoes in the region; the “fire-spewing mountains” Duché claimed to have witnessed were probably the Smokies, with their low-lying sheaths of clouds resembling smoke. In any case, Duché was reported to have “an artful Knack of talking,” and his travel stories reveal that he was more a poetic fantasist than a reliable reporter of observed facts. He trafficked in curiosities and marvels: volcanoes in the Appalachians, marble quarries, mysterious caverns, and white gold.

Many years later, Cherokee Indians near Franklin reported that a “Frenchman”—evidently Duché—had “made great holes in their Land, took away their fine White Clay, and gave em only promises for it.” We know that the clay that Duché found in the Carolina outback was a remarkably pure kaolin, free of the traces of iron and other minerals that would discolor it when fired at high temperatures.

We find Andrew Duché, the first documented potter to practice his craft in Georgia, at the start of many forking paths. He stands at the origin of the great Southern stoneware tradition; he is among the first in the English-speaking world to embark on the quixotic quest for the secret of making Chinese porcelain; and we find him collaborating, in interesting and still mysterious ways, with American Indian artists.

8.

As it turned out, none of these dramatic discoveries were of much use to Andrew Duché. His early life makes clear that he was bold, improvisational, and brilliant. From urbane Philadelphia, he made a new life for himself in the rough and embryonic towns of the Georgia frontier. He worked closely with local Indians on his experiments, but he was also, apparently, insensitive to the Cherokee people whose clay he carted off. Moreover, he seems to have lacked the business acumen to make a fortune from his discoveries.

Failing to find adequate financial support for his porcelain production in the small towns of Georgia, Duché traveled to England in 1743. There he met with Thomas Frye and Edward Heylyn, Quaker entrepreneurs who established the Bow Porcelain Factory. On the basis of what Duché told them, Frye and Heylyn applied for a patent to make porcelain with Cherokee clay, or unaker—the name derived from the Cherokee word for white. Duché seems also to have met at the time with William Cookworthy, a Quaker chemist in Plymouth, who was experimenting with porcelain. Recent chemical analysis of certain porcelain teapots and teacups marked with a blue A, from various British collections, confirms the outlines of this account. Both the expertise and the clay for making high-quality porcelain in Great Britain seem to have come from the American colonies, and specifically from Duché.

Despite all this energetic networking, Duché was destined to be disappointed in his aim to be the leading figure of porcelain manufacture in the English-speaking world. If he inspired potters in Britain, he seems not to have benefited personally from it. During the 1740s, a vein of bitterness entered his dealings with Georgia authorities. He joined the proslavery faction known as the Malcontents, gave up making pottery, and worked as an Indian trader instead; at one point, he sought permission to build a road from Charleston to Keowee, the nearest town in Cherokee country and the first leg of the route to the white clay beds. Duché eventually returned to Philadelphia, where he died in 1778.

9.

Yet another path that Duché helped to inaugurate concerned the innovative use of glazes, specifically what has come to be known as the alkaline ceramic tradition.

There were actually two secrets of Chinese porcelain that intrigued the Georgia and South Carolina potters of Duché’s generation: One was the secret of the clay, and one was the secret of the glaze. Southern potters were fascinated by the silky white and green celadon glazes on Chinese porcelain and sought to reproduce them. A history of China by a Frenchman, Jean-Baptiste Du Halde, first published in 1735, included a description of porcelain production using olive-green glazes made from a mixture of lime, plant ash, and powdered flint. Copies of the book were in the Charleston Library, and excerpts were published in the South Carolina Gazette in 1744.

It was in Du Halde’s history, presumably, that Dr. Abner Landrum, a key figure in the history of early American pottery, first came across recipes for how to make celadon glazes. Landrum (1784–1859) was a farmer and physician, the publisher of a local newspaper called the Edgefield Hive, and, with his two brothers, a potter of considerable ambition. Landrum built an extensive pottery village in the Edgefield area, known as Pottersville, across the Savannah River from Augusta; it produced jugs and other household wares during the nineteenth century. The Landrum family had its roots in Randolph County, North Carolina; the Landrums were related to the great potting family of the Cravens, from the Seagrove and Jugtown neighborhood. Landrum’s passion for porcelain spread to the naming of his sons after famous ceramic manufacturers, including Wedgwood and Palissey.

Dr. Landrum relentlessly pursued his experiments in matching Chinese celadon glazes. Eventually he found the right combination of lime, leaf ash, and quartz—cheaper materials than the customary salt—to achieve what we now know as the alkaline glazes of North and South Carolina: brilliantly expressive browns and greens that are fully alive today in potteries all over the South.

And yet Dr. Landrum’s greatest contribution to Southern pottery may well have been something entirely different, not an innovation in glaze but rather the creative opportunity that he provided for one of his gifted apprentices. In 1859, a slave employed at the Edgefield Pottery inscribed the following words on a great storage jar:

When Noble Dr. Landrum is dead

May guardian angels visit his bed.

The potter-poet’s name was Dave. As the depth of his achievement has become increasingly known in recent years, Dave has emerged as a towering figure in the history of American ceramics. His idiosyncratic achievement in the writing of poetry also deserves to be more widely known.

One of Dr. Landrum’s business partners at Edgefield was his nephew Harvey Drake, who was Dave’s first owner. Slaves were employed for much of the heavy work at Pottersville. The young slave known as Dave, born around 1800, learned to turn pots in his teens. His skill was recognized early, and he was soon making storage jars and other vessels of extraordinary dimensions and formal grace. Just as remarkably, Dave learned to read, a forbidden skill for a slave, for it was felt that literate slaves would be more likely to rebel. Dr. Landrum employed Dave at his newspaper, the Hive; it seems likely that it was Landrum, later a Unionist, who taught Dave to read and had him set type for him.

Dave was also employed for a time in a brickmaking enterprise. A brick has been discovered at Edgefield with his signature incised into it. It seems reasonable to conclude that Dave practiced his writing skills by writing in brick with a stick.

Dave Drake was a brilliant potter. But he was also a poet. His storage jars are of a virtuoso grandeur that still fills potters with awe. His most visionary stroke, however, was to combine his two skills in a manner unprecedented for slaves or, for that matter, for anyone in American pottery. Dave inscribed his poems, generally consisting of a single rhymed couplet, directly onto the shoulders of his great jars.

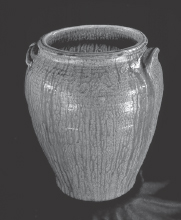

David Drake jar, 1862, inscribed with the words “I made this Jar.”

Dave’s poems can seem naive in their use of slang, odd rhymes, and high-flown language drawn from the Bible and other sources. But they are no more naive than Emily Dickinson’s poems, which also self-consciously adopt folk phrasing and peculiar rhymes. Both poets favor short, incisive, enigmatic lines, like bolts of lightning in a dark night sky.

Many of Dave’s poems are self-referential; they refer to the pots and the potter-poet. It is as though Dave is giving the pots voice, speaking through their mouths and lips, as in this inscription from May 1859:

Great & Noble Jar

hold Sheep goat or bear

or this pot made at the height of the Civil War:

I made this Jar all of cross

If you don’t repent, you will be lost.

In an early poem of 1840, when Dave was owned by a relative of Landrum’s named Lewis Miles, he punned on the double meaning of oven, as both pottery kiln and kitchen stove:

Other poems reach into a wilder, more mysterious register of poetic association, as in this dazzling couplet inscribed on a pot during the summer of 1857:

A pretty little Girl, on a virge

Volcaic mountain, how they burge

The poem speaks of the “volcanic” change in a young woman’s desire as she moves from the “verge” of virginity to the “burgeoning” of mature sexuality. Emily Dickinson referred to herself, around the same time, as “Vesuvius at Home.” But there is also a deep connection in the poem between sexual transformation and what happens in the volcanic regions of the kiln.

Dave Drake threw pots and wrote poems against a background of incredible violence, personal loss, and, late in life, the chaos of the Civil War. He lost track of his wife and children in the hideous institution of the slave trade, a loss commemorated in one of his most moving poems:

I wonder where is all my relation

Friendship to all—and every nation.

One of the women who worked beside him in the Edgefield pottery was whipped so severely that she committed suicide. And when he was around thirty-five, Dave fell asleep, drunk, on the railroad tracks. A passing train severed one of his legs.

Such tragedies make the big-hearted spirit of Dave’s pottery and his poetry even more moving. “Friendship to all—and every nation.”