1.

I grew up in a placid town in Indiana, close to the Ohio border, that boasted a Quaker college, a school-bus factory, and a brown, lackluster river called the Whitewater. The river cut the town in two, both geographically and morally. No liquor was sold on our side of the river, the “dry” or Quaker side. On the opposite bank, down in the bedraggled gully known as Happy Hollow, were the ruins of the Gennett record company, where some of the classic jazz recordings of the 1920s, by New Orleans luminaries such as Jelly Roll Morton and Louis Armstrong, were pressed. A railroad was strung precariously along the river, and this, presumably, brought the unruly jazzmen to our town as they headed for Chicago. The Whitewater River, after wending its sluggish way through cornfields and limestone gorges and more nondescript small towns, dumped its murky contents into the far more impressive Ohio.

Our town was peaceful, as I say, almost officially so. Quakers opposed to slavery had come up from the Piedmont of North Carolina and Virginia early in the nineteenth century. Nostalgic for the fertile meadows and early spring of the South, they named their new settlement Richmond after their old capital city. Richmond had been a major “station” on the Underground Railroad before the Civil War, when Levi Coffin, the famous “conductor” of the railroad, lived in the area, and the town had remained, uneasily, a Quaker town. Growing up there during the Vietnam War, I knew many conscientious objectors—pacifists opposed to all war who, when drafted, were allowed to perform alternative service in hospitals or prisons instead of serving in the military. I didn’t know a single soldier. My own older brother had filed for CO status when he reached the age of eighteen in 1968, which turned out to be a big year in the history of Richmond, Indiana.

Like children in small towns everywhere, we complained that nothing ever happened in Richmond. And then, one hot afternoon in April 1968, something did, when six blocks of our downtown disappeared in a gray mushroom cloud. Rumor had it that local whites, wary that racial violence might spread from Chicago in the wake of the murder of Martin Luther King, had stockpiled explosives and weaponry in a sporting-goods store named, as I remember, Marting Arms. These men despised the Quakers as “nigger lovers,” but a gas leak turned their own weapons against them.

I had been playing string quartets in an old office building downtown earlier that Saturday, under the tyrannical eye and ear of an unforgiving German named Koerner.

I had barely crossed the Whitewater River, carrying my black viola case as I trudged across the G Street Bridge, when the explosion occurred. I watched the cloud unfurl in the blue sky like some Cold War nightmare of unutterable disaster, the kind we were warned about, cowering under our desks, during our civil defense drills at school. Forty-one people died that afternoon and more than 120 were injured, random victims of their neighbors’ fear and folly.

Several days later, as my friends and I helped in the cleanup, there were still unexploded shotgun shells along the rubble-strewn streets. The town fathers used the federal disaster relief funds to turn the downtown into a pedestrian mall, thus inadvertently delivering the death blow to an already moribund cluster of stores and two dank and dreary movie theaters, the State and the Tivoli, where we huddled on Friday nights dreaming of distant love and violence.

2.

Many years later, when I had all but forgotten the explosion and was teaching—as I had always promised myself that I would never do—at a small college in a small town, just as my father had done before me, an unfamiliar student dropped by my office to ask if she might do an independent study with me on the Beat poets. To my surprise, she mentioned that she, too, had grown up in Richmond, Indiana. We had a long talk about every detail of the failed downtown: the terrible bookstore that didn’t sell books, the more terrible restaurant that didn’t sell food, and the area down by the Gennett factory on the river, which had become, she told me, something of a tourist destination for jazz fans.

I was about to turn fifty, and I had found myself surrendering increasingly to a retrospective mood tinged with a faint but unspecified melancholy. With her hair dyed pitch black, her ironic wit, and her taste for Kerouac and Gary Snyder, this messenger from the past brought Richmond back to life for me.

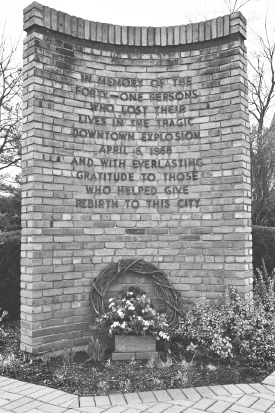

A week after our first conversation, I received an e-mail message from the dean, informing me that my student had dropped out of school. A few weeks later, back in Richmond, she sent me a photograph of the monument erected in memory of the victims of the 1968 explosion.

The monument, as I could see from the photograph, was a concave wall of neatly laid red brick, with gray lettering matching the color of the mortar. I could easily imagine my mother’s father, a brick mason, subjecting this curved wall to scrutiny. The wall was one brick length (or stretcher) wide, and every sixth row was made up entirely of the widths (or headers) of brick laid side by side. At the top of the wall was a single line of much darker brick, the high-fired variety known as blue brick. And above this line, as a sort of crown, was a row of bricks laid vertically.

Someone had clearly given some thought to all these details, probably with Maya Lin’s Vietnam Veterans Memorial in mind, though the meaning of all this virtuosic brickwork wasn’t entirely clear. As for the gray lettering, the design committee must have struggled to find words for the accidental deaths of so many blameless people, like travelers on the Bridge of San Luis Rey. They finally settled on this inscription:

In memory of the forty-one persons who lost their lives

in the tragic downtown explosion April 6, 1968

and with everlasting gratitude to those

who helped give rebirth to this city

3.

The year following the explosion was a turning point for me, as though its seismic force had shaken something loose in my own convictions. Although I had grown up on the Quaker side of the river, I had worked hard at fitting in with the “ordinary” kids, as I imagined them to be, who lived on the opposite bank. I distanced myself from the other faculty brats in my neighborhood, the sons and daughters of professors at the Quaker college. I was furtive and ashamed of my black-cased viola, and what few books I borrowed from the children’s floor of the Morrison-Reeves Library—mainly fairy tales, in purple and green bindings, and books about American Indians—I read on the sly.

Instead, I played on the basketball team, more a religion than a sport in Indiana, kept my hair short, and pursued blond-haired girls with names like Rhonda.

Rhonda—how exquisite and American and sexily ordinary she looked in her pleated Scotch-plaid skirts. Her golden hair was long and straight, as though it had been ironed—perhaps it had been—and I touched it warily, like a talisman that might change me, straighten me out, when we played nervous games of spin-the-bottle at parties. My own hair, first “wavy” and then increasingly curly with a dangerous tendency toward frizz, was to me the most alarming of the symptoms of puberty. That seemed the safest attribution, warding off some deeper cause: my Jewish ancestry on my father’s side or some buried secret from my mother’s Southern generations.

I tried a chemical straightener and I tried a hairnet. I slept with one hand firmly pressed against the side of my head to keep the rebellious hair in place. Something more drastic was needed. I ventured warily into the African American barbershop near the library, down the street from the Specialty Records store that sold “race records.” There, as I sat nervously in the thronelike chair and listened to the banter of the barber and his cronies, my hair was cut and treated with foul-smelling potions. The results were disappointing. One day, a black teammate took me aside during basketball practice and asked, softly and affectionately, “Chris, you got nigger blood?”

The annual basketball dinner, when team members were celebrated one by one, was a mixed bag for me, part honor and part humiliation. I loved to receive the trophy and the athletic letter for my warm-up jacket, but the fathers-and-sons game that followed was excruciating. While the other ordinary dads—the police officers and grocers and insurance salesmen—mixed it up with their sons, doing trick shots and behind-the-back passes, my father stood awkwardly on the sidelines in his coat and tie and his German, Henry Kissinger accent. He could no more play basketball than fly to Mars. When my friends asked me if my father played any sport, I told them helplessly, and with wild exaggeration, that he was a mountain climber.

During the months following the downtown explosion, I went through a kind of slow-motion change, a transformation that I still don’t fully understand. The pressure of starring on the eighth-grade basketball team—I was the starting center and the team captain—and the endless practices, one beginning at seven in the morning and another following the end of classes, came to seem onerous to me. I found it harder and harder to get out of bed in the morning, and I slipped into a bottomless teenage lethargy. Abruptly, surprising even myself, I announced to the basketball coach, an ineffectual man in white tennis shoes named Eccles, that I was quitting the team.

This, it turned out, was not so easily done. Mr. Eccles called me repeatedly, coaxing and cajoling me by turns. “I am very disappointed in you, Chris,” he said (he pronounced it CREE-us). “You could be a real star on this team. If you come to practice tomorrow, I promise that nothing will be said against you.” And then the star of the ninth-grade team, Trent Smock, called me as well. Trent Smock was an idol of mine, and I remember thinking, well, if Trent Smock wants me to play, maybe I should play. But I stuck to my decision.

A few days later, as I was shooting baskets in our driveway with my friend Bobby Beales, Bobby allowed as how he wouldn’t mind having a girlfriend. “Well, I’m all set,” I said complacently, since Rhonda and I had been “going out” for almost a year. “No, you’re not,” Bobby said, with a cruel satisfaction that I had never heard in his voice before. “Rhonda was at the high school game last night, and she said you’d changed.”

And then he added, as though he believed it too, “You’re different.”

4.

Leaving basketball put me in touch with another part of myself. For many years, I had indulged in survivalist fantasies. I tried to live on milkweed shoots and wild sorrel, harvested from the wasteland beside the driveway, and I studied a book by Euell Gibbons called Stalking the Wild Asparagus. The life that the Indians had led, close to the ground and the bare essentials of existence, appealed to me. Our ranch house—an absurd misnomer, given its modest proportions, really a couple of parallel hallways with a narrow kitchen in one and four cramped bedrooms opening from the other—was on the edge of town.

Fields opened directly beyond the row of scraggly apple trees in our backyard—planted, I firmly believed, by Johnny Appleseed himself. As far as I was concerned, the wilderness began right there. To venture deeper into the woods, my friends and I mounted our bicycles, stabled in the garage like trusty mules. We peddled down the meandering curves of Abington Pike—Doug Nicholson, Joel Barlow, Jeff Nagle, and I, Quaker renegades all—out beyond the fields and into rougher country.

About a mile beyond the sign that said, to our delight, city limits—it always reminded me of a television show about paranormal activity called The Outer Limits—we found the opening in the woods where a secret path led down through stinging nettles to the swimming hole. Here, the Whitewater River abruptly narrowed and purled between great outcroppings of blue-gray shale stuccoed with fossils. Along the banks of the river and above the nettles were mulberry trees, laden with red and purple fruit. We ate them by the handful, staining our hands as the nettles mottled our legs, with stinging splotches that looked like more mulberry stains. Then, the harvest over, we were back on our bikes, flying pell-mell downhill past Curtis’s farm, its stagnant pond clotted with cattails and no longer fit for swimming. Farther, around a turn in the pike and onto a gravel road, we heard the sound of rippling water: Blue Clay Falls.

We rode right in, like cowboys in a Western, our bicycle spokes flicking water into rainbows in the sunlight. The falls were no more than rapids, really, cascading over a broken staircase of low-lying shelves of shale, filled with oozing blue clay like Napoleons stuffed to bursting. Bluish, translucent crayfish—we called them crawdads—skittered out in alarm when we poked at the clay with our toes.

The mood in the woods wove its spell: the sun filtering down through the high, wind-brushed foliage; the eerie silence except for the trickle and meander of the falls; the sense that animals and birds, invisible but near, were watching us expectantly, intruders in their lair.

Once, as we were dozing by the falls, our backs propped up against moss-bearded oak trees, Doug Nicholson, rummaging in the woods, came across a pile of Playboy magazines held in place by a chunk of limestone—someone’s private stash of woodland joy. Suddenly, we were all wide awake, reaching over one another’s shoulders to turn the pages with snickering awe. Someone ripped out a centerfold, and that was the signal. We tore the magazines to pieces in gleeful celebration.

And then, as though this, too, was part of the agreed-upon ritual, we stripped down to our boxers and slid into the shallow creek. We pried handfuls of cold blue clay from between the rocks and covered our faces and bodies with it, working it into our hair. We barely knew ourselves. Our bicycles could wait. Our families could wait. We were in another world now, hieroglyphed in blue. Our pockets under the sheltering trees should have been filled with grapeshot and pemmican.

5.

During the summer of 1969, a year after the downtown explosion, I was fourteen and getting ready to leave Indiana and basketball for good, to enroll in a progressive boarding school in Vermont. The change that Rhonda had referred to was pretty much complete. I had let my hair grow, and the incipient curls had flourished into an Afro. I was reading books from the upstairs (adult) section of the Morrison-Reeves Library, by Huxley and Saint-Exupéry. I was beginning to wonder what I might do with my life. That summer, I whiled away the time by helping to excavate an Indian mound in the middle of a cornfield near one of the small towns along the Whitewater River. I thought at the time that I might want to be an archaeologist.

My father taught chemistry at the Quaker college, and three students there, the archaeological team, were happy to have an assistant for the dig, someone to wield a shovel rather than a toothbrush. The undertaking seemed wildly romantic to me, and I had vague ideas about gold trinkets and bones and secret passageways lurking in the mound. Each morning, the college students, a woman and two men, stopped by our house in a battered blue pickup truck. They were long-haired and easygoing, but very serious about their work on the mound. We drove out of Richmond on the old National Road and then across flat cornfields to the roped-off site, easily discerned as a rise or swelling in the ground.

Then our long day under the hot Indiana sun would begin. The field was redolent of sweat and feed corn, and the fat flies hovered lazily over the dig. A battered transistor radio droned Top Forty songs from a station in Dayton, Ohio. Hours of patient probing with blade and brush would bring to light a bit of mica or a shard of ceramic earthenware or a fragment of worked shell—the luxury goods traded by the Hopewell culture that inhabited the region from about 500 b.c. to a.d. 1000. I mainly sat and listened and watched, until some sifted dirt had to be shoveled out of the excavated area.

The students told me that there were ancient burial mounds and monuments all over the Ohio River Valley and beyond, built by unknown tribes called, for want of a better name, the Mound Builders. The mounds were minimalist earthworks etched directly into the landscape by visionary artists who made the world their canvas. Early European travelers in America were convinced that the mounds, some of them quite intricate in their geometry, were too sophisticated for the local Indians to have built, so they came up with the idea of a mythical people—wanderers from Wales or Phoenicia, perhaps, or a lost tribe of Israelites—who had preceded the Indians.

“May Plato’s Atlantis have once existed?” the French writer Chateaubriand wondered in his Travels in America and Italy, as he journeyed through the colonies in 1791 in search of the Northwest Passage. “Was Africa ever joined in unknown ages to America? Be this as it may, a nation of which we know nothing, a nation superior to the Indian tribes of the present day, has dwelt in these wilds. What nation was this? What revolution has swept it away? When did this happen? Questions which launch us into the immensity of the past, in which nations are swallowed up like dreams.”

6.

The year 2009, the year in which I write these words, seems impossibly far away from 1969, as impossible to imagine as growing up. I am now fifty-four, older than my father was as he stood dutifully on the sidelines of the fathers-and-sons basketball game. I can now begin to imagine what it was like for him, a stranger among strangers. At fifty-four, life, at least my life, is as much a task of recovery as of acquisition. The uncertain prospects ahead are weighed against the magnetic pull, stronger every day, of retrospect. To own one’s past and the past of one’s family takes on a peculiar urgency. The archaeological impulse is a trust in the importance of origins, of beginnings.

7.

Sigmund Freud was a great smoker of cigars and a passionate collector of antique objects. He once told his doctor that his love for the prehistoric was “an addiction second in intensity only to [my] nicotine addiction.” Freud’s consulting room was a private museum, the glassed-in bookcases covered with statuettes and fragments excavated in Greece, Rome, and Egypt. The famous couch, piled high with pillows, was draped with an antique Persian rug, a Shiraz. Freud’s hero was Heinrich Schliemann, the famous digger and discoverer of Troy. And Freud’s favorite metaphor for the layering of the human psyche was drawn from archaeology. He told the patient he called the Wolf Man that “the psychoanalyst, like the archeologist in his excavations, must uncover layer after layer of the patient’s psyche, before coming to the deepest, most valuable treasures.” As he reminded us, Saxa loquuntur. The stones speak.

8.

I am searching in this book for a pattern in the wanderings of my far-flung family. But the narrative has more to do with geology than genealogy. I take my promptings from the material order of things, and especially from the clay—whether the dark, iron-rich clay of red brick or the white clay of Cherokee pottery and fine porcelain—that is a recurring motif in the book. My own memories take up relatively little space.

The first section evokes the red-clay world in rural North Carolina where my mother grew up. The daughter and granddaughter of bricklayers and brick-makers, she was raised on the edge of the Piedmont, where the economy is based on tobacco and red brick and where folk potteries reaching back two hundred years dot the country roads. The beautiful vases and bowls of the famous pottery at Jugtown, where Chinese and Japanese shapes fused with native traditions, gave her an early sense, in her own vocation as an artist, of why art lasted and what it was for. At the very moment when she prepared to leave this red-clay world, a tragic romance cracked her young life in two.

The second section moves west into the Appalachian foothills, to the visionary experiment in education and the arts undertaken at Black Mountain College. I retrace the journey of the artists Josef and Anni Albers, from their background in the famous Bauhaus in Berlin to their fresh start in the New World. Josef and Anni were my father’s uncle and aunt; Josef ran Black Mountain College during the 1930s and 1940s, when its tremendous impact on American culture was greatest and Black Mountain students and teachers included Robert Rauschenberg, John Cage, and many others. The Alberses taught via materials; their deepest lessons lay in the contrast of textures—brick and wood, pebble and leaf. But they also taught by example, as Anni said, by fearlessly “starting from zero.” In the contours of the mountain roads, they discerned hidden messages, marks of home.

The third section moves farther west and further back in time, as I tell the extraordinary story of the eighteenth-century quest for “Cherokee clay.” Operatives from Wedgwood and other potteries combed the dangerous North Carolina outback, riven by Cherokee fighters amid the opening salvos of the American Revolution, looking for the silken-white clay that is needed to make fine porcelain. One of my ancestors, the Quaker explorer and naturalist William Bartram, was a tangential participant in this quixotic search. Bartram’s hallucinatory travel journal fired the imaginations of the Romantic poets Coleridge and Wordsworth. “Kubla Khan,” Coleridge’s great opium-inspired poem, is, among other things, a dream of Carolina.

The title, Red Brick, Black Mountain, White Clay, names the three paths, each mapping the experiences of relatives or ancestors of mine trying—by art, by travel, or by sheer survival—to find a foothold in the American South. Heavily invested in memory, the book moves backward in time and westward in space as it digs successively deeper into the dirt and rock of the North Carolina outback.

9.

Remember the story of Hansel and Gretel. When they are led into the dark wood by their bitchy stepmother and acquiescent father, Hansel leaves a trail of white pebbles, secretly dropped from his pocket one by one. Brother and sister find their way home by following the serpentine path of pebbles. “And when the full moon had risen,” as the North Carolina poet Randall Jarrell translates it, Hansel “took his little sister by the hand and followed the pebbles, which glittered like new silver coins and showed them the way.”

Starting out, I imagined a straightforward book in three parts, moving along a taut narrative path with a sturdy foundation of clay undergirding all. Books have their own fates, however, and research—at least the kind of research that I practice—yields to serendipity. If the destination is known beforehand, what’s the point of the journey? A provisional map of the whole allows the woolgathering pilgrim to get a little lost along the way without losing his bearings completely. Meanwhile, coincidences and chance meetings confirm a certain rightness, a fit, in the meandering quest.

Midway, someone asked me, out of the blue, to write an essay about Karen Karnes, the major potter of Black Mountain College. Midway, the fact of James McNeill Whistler’s North Carolina roots and his North Carolina mother—surely the most familiar mother in American art—muscled its way into the proceedings. Midway, I discovered that the uncanny parallels I had sensed between two tragic young men in my narrative, Sergei Thomas and Alex Reed, were even closer than I had suspected. One learns to trust these promptings as confirmation rather than distraction. Sometimes, the shortest path between two points is serpentine.

For me, however, the true beginning of this book lay in red clay. I began writing at the precise moment when I realized, in a flash, that the iron-rich Carolina clay that formed the bricks my grandfather laid was dug from the same hills and streambeds that yielded the earthenware pots of Jugtown.

Now is the time to stake out the area with a taut white string and dig down carefully, one layer at a time, into the mound of memories. And when the hard work with picks and shovels yields to the more delicate probing with blade and brush, I’ll sift through the red dirt and white sand, looking for shards and fragments and anything else of interest that might lie buried there.