Compared to other species of livestock, little is known about how the turkey was first domesticated. What is known is that the wild turkey is indigenous to the Americas and was kept by Native Americans centuries before the arrival of Europeans. Various tribes ate turkey eggs, as well as turkey meat both fresh and dried as jerky.

Spanish explorers of the early sixteenth century brought turkeys to Europe, where the birds were selectively bred for a couple of centuries before being brought back to America by early settlers. From those birds sprang the supermarket turkey we know today.

Turkeys are, in many ways, similar to chickens, and the best way to get started raising turkeys is to first raise some chickens. Even though turkeys are much bigger than chickens, they can be quite a bit touchier. Baby turkeys cost about seven times more than baby chicks, yet chicks are more forgiving of common mistakes made by poultry novices. And you can raise a batch of broiler chicks in about half the time needed to raise turkeys to harvest weight. So it makes sense to practice poultry husbandry on chickens and then use your newfound knowledge to try your hand at raising turkeys, especially since both require much the same sort of facilities.

Choosing a Breed ....................................................................... 50

Raising Poults ............................................................................. 54

As They Grow .............................................................................. 58

Poult Health ................................................................................. 60

Predation ....................................................................................... 63

Butchering .................................................................................... 64

Breeding Turkeys ..................................................................... 66

Many turkey breeds are available to choose from, not all of which are desirable for home meat production. In selecting the best breed for you, consider some basic criteria: how big they get, how fast they grow, how they will look in your yard or on your table, and how self-sufficient and hardy they are.

1. Size matters. A dressed turkey must conveniently fit into your refrigerator while it is aging, and into your oven while it is roasting. If you plan to harvest all your turkeys at once, you also need to have enough freezer space to store them all; if your home freezer isn’t big enough, you will have to rent a locker. The other option is to harvest each turkey as you are ready to roast it, which stretches out the amount of time you have to feed your turkeys (therefore the cost of raising them). And the older they get the less tender they become.

2. Color considerations. The majority of turkeys raised for meat have white feathers, because white pinfeathers are less visible on a roasted bird. Dark or black pinfeathers on a roasted turkey on the platter look awfully unappetizing. Some of the nonwhite breeds have light-colored pinfeathers that don’t show much. On the other hand, if you plan to breed turkeys to raise their young for meat, you want birds you find aesthetically pleasing. Turkeys are large, imposing birds that will be highly visible in your yard.

Another color consideration is the amount of white meat a turkey produces. The broad breasted strains have been selectively bred to have a large chest, because consumers have been conditioned to prefer lots of white meat. However, white meat is not as succulent or flavorful as dark meat.

The heritage breeds don’t grow as large as the broad breasted strains, and therefore are more suited for a small family.

3. Heritage breed versus commercial strain. Industrially produced turkeys are selectively bred broad breasted strains originally developed from standard breeds. The standard breeds are those that were accepted into the American Poultry Association Standard of Perfection in the late eighteenth century. Now called heritage breeds, they include (among others) the Black, Bourbon Red, Bronze, Narragansett, and Royal Palm. Raising a heritage breed for meat helps support the turkey breeders who choose to maintain the genetic lines of these minor breeds. But that’s not the only reason why a heritage breed can be ideal for family meat production.

The heritage breeds don’t grow as large as the broad breasted strains, therefore are more suited for a small family with limited refrigerator and oven space. On the other hand, if you’re into white meat, the breast of a heritage breed is about half the size of that of a broad breasted strain.

The heritage breeds are better foragers and have greater disease resistance than industrial strains, making them more suitable for raising on pasture. On the other hand, they grow at a much slower rate, finishing in 6 to 7 months where the broad breasted strains are ready to harvest in 4 to 5 months. A heritage turkey meat project therefore requires an extra two months of labor, but the reward is juicier, more flavorful meat.

Talking Turkey

A baby turkey of either gender is a poult. A young male turkey under 1 year of age is sometimes called a jake, and a young female is a jenny. A mature female is a hen. A mature male is a tom or gobbler.

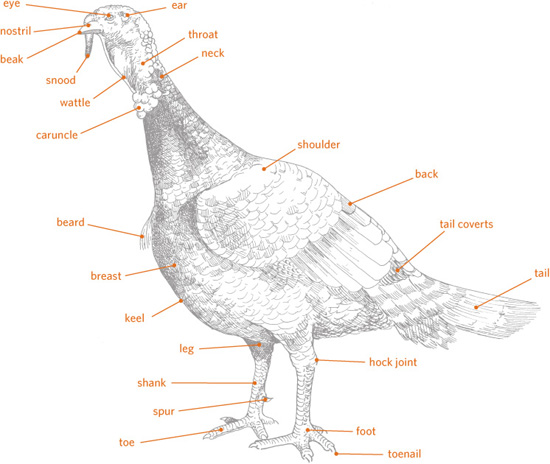

Taxonomically, turkeys are the largest members of the order Galliformes, comprising chicken-like birds. Indeed, a turkey is often described as a large chickenlike bird with a fan-shape tail. Along with chickens, turkeys are in the family Phasianidae, which includes pheasants and peafowl. Their genus, Meleagris, includes Meleagris ocellata, or the ocellated turkey of southeastern Mexico, northern Belize, and Guatemala, and Meleagris gallopavo, the wild turkey of North America from which today’s domesticated turkeys were developed.

Finally, should you decide to keep your best tom and a few of your hens so you can raise poults of your own, be aware that the broad breasted strains cannot mate naturally because they are too awkward due to their enormous weight and outsize chests. Propagating a broad breasted strain requires artificial insemination.

Quick Guide to Turkey Breeds

Of the many turkey breeds available, some are bred primarily for exhibition while others are extremely rare and costly. For the turkey raising novice, the following breeds are worth considering.

Black. Originating in Mexico, the Black turkey was brought to Europe by early explorers, then brought to the United States by early settlers. Although it has black feathers, it remained a popular meat bird for centuries because of its calm disposition, rapid growth, and early maturation.

Bourbon Red. One of the older breeds developed in the United States, the Bourbon Red is named after Kentucky’s Bourbon County. This handsome heavy breasted bird has chestnut-colored feathers accented in white- and light-colored pinfeathers. The Bourbon Red is an active forager and is good for pest control.

Broad Breasted White. Selectively bred by industrial producers for fast growth and a large breast, the Broad Breasted White accounts for some 90 percent of all turkeys grown for meat. Although it is suitable for family meat production, it cannot be used to breed future turkeys because its rapid growth leads to heart problems, and its heavy weight results in lameness and an inability to mate naturally.

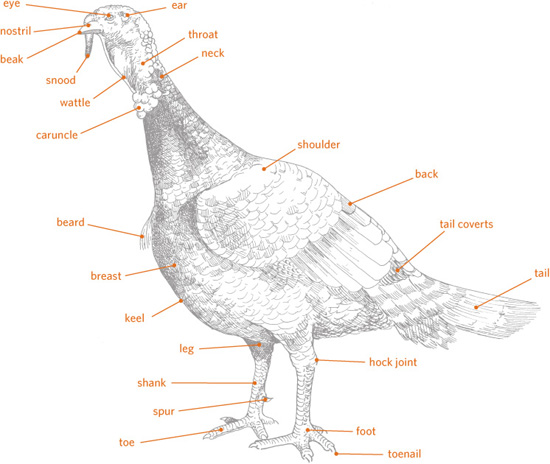

Broad Breasted Bronze. Once the main commercial turkey until the Broad Breasted White was developed, the Broad Breasted Bronze is the hardier of the two, but its dark multicolored feathers with a coppery hue result in a less clean-looking dressed bird. Like the Broad Breasted White, this heavy turkey is too clumsy to breed naturally, and artificial insemination is required in order to raise future poults.

When the tom turkey opens out his fantail and struts his stuff, he looks absolutely beautiful, but close up he’s as strange looking as they come. The tom has no feathers on his head and neck and his face is covered with fleshy caruncles that vary in color from pink to pale purplish blue to nearly white. A loose growth called a snood hangs from the top of his beak, a fleshy pouch called a wattle dangles beneath his beak, and a beard grows from his chest. To make things more interesting, when the tom gets excited his snood gets long and floppy and his caruncles turn a brilliant red.

The hen looks much like the tom, but is smaller and less colorful. She may or may not have a beard growing from her chest, and she may occasionally spread her tail and briefly strut like a tom, although her tiny snood won’t grow long and floppy and her face doesn’t light up like the tom’s.

Close up, a tom looks downright weird.

Bronze. Ancestor to the Broad Breasted Bronze, the Bronze turkey was developed by early American settlers by crossing Black turkeys brought from Europe with local wild turkeys. The resulting birds have dark pinfeathers. The Bronze turkey looks similar to the Broad Breasted Bronze, but it is smaller and able to reproduce naturally.

Midget White. Developed in Massachusetts as a small turkey for backyard production, the Midget White is the smallest of the turkey breeds and an ideal size for a small family. With its broad breast, the Midget White looks like a miniature Broad Breasted White, but its much lighter weight gives it the ability to fly really well—an important consideration when designing facilities intended to keep turkeys in.

Narragansett. Developed in Rhode Island by early settlers as a cross between Black turkeys brought from Europe and local wild turkeys, the Narragansett is similar in color to the Bronze but has a steel-gray tint in contrast to the bronze’s copper cast. It is known as an excellent forager with a pleasant disposition, good egg production and brooding instincts, and early maturation.

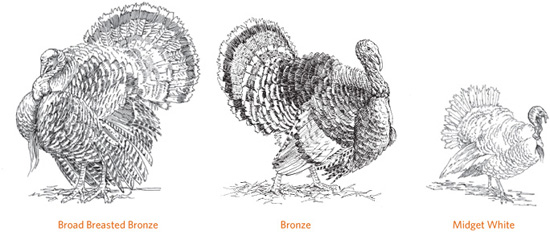

Royal Palm. Developed in Florida, the Royal Palm turkey appears to be basically white until the tom opens his tail to display stunning bands of black feathers. Having never been selectively bred for fast growth and heavy muscling, Royal Palms are considered primarily ornamental, but they are a nice size for a small family. They are active foragers and good flyers, an important consideration in designing facilities for them.

The Midget White is an ideal size for a small family.

Turkeys can be tricky for a novice to raise. Because a turkey is curious about things, it tends to get itself into trouble, such as wedging its body into a tight spot and not having any inclination to back out. Young turkeys tend to pile on top of one another when cold or frightened and those on the bottom can be smothered. And sometimes a poult dies without apparent cause, which is more common with poults that have endured the stress of being shipped by mail compared to those hatched locally, and more so among broad breasted strains than among standard breeds.

Broad breasted strains run a few dollars less per poult than standard breeds, but don’t let that be your main consideration in making your purchase. Because the broad breasted strains don’t have as strong an immune system as the standard breeds, their lower price is somewhat offset by greater losses.

For these reasons, start your first turkey project with small numbers, but not too small. Anywhere between a dozen and two dozen poults should be few enough for you to keep track of and learn from, but not so few you are likely to lose them all before Thanksgiving rolls around.

Most hatcheries sell poults as straight run, meaning the number of males and females is the same ratio as whatever hatches. Some hatcheries offer sexed poults in the broad breasted strains, so you could purchase only males or only females. Since toms and hens grow at a slightly different rate, with sexed poults all the turkeys will be ready to harvest at the same time—an advantage for commercial production but not necessarily desirable for turkeys raised at home.

The broad breasted strains are ready to harvest in 4 to 5 months, so if you start your poults in June or July they will be ready to dress in time for Thanksgiving and Christmas. The heritage breeds are ready to harvest in 6 to 7 months, so start them in April or May. You don’t have to harvest all your turkeys at the same time, although the longer you keep them the more expensive they become to feed.

Almost any hatchery that sells chicks sells poults as well. Place your order early in the year, especially if you want one of the less common breeds, to ensure the hatchery doesn’t sell out. Ordering well in advance also gives you plenty of time to get your brooding facility set up.

Prepare your brooding area well before the poults are scheduled to arrive. Turn on the heater a day ahead, so the bedding and floor have time to warm up and not draw heat away from the new arrivals. With the brooder warmed up, check for drafts and take measures to eliminate any you find. Fill the drinker well ahead, so the water will be brooder temperature for the poults’ first drink.

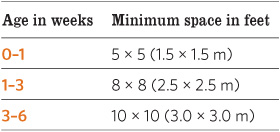

Poults need to be brooded for five to six weeks before they are big enough to be put out on pasture. For the first week or so the poults don’t need much room, but as they grow they need more space to move around. Providing sufficient space reduces stress, helping prevent the poults from becoming frustrated and picking on each other. An initial brooding space of 5 feet by 5 feet (1.5 × 1.5 m) is adequate for two dozen poults. The brooding area must be secure from all predators, including dogs, cats, rats, weasels, and snakes.

For warmth and comfort, cover the brooder floor with a thick layer of bedding. Good bedding materials include shredded paper, well-dried grass clippings, rice hulls, and pine shavings (but not cedar shavings, which are toxic to poults). Until the poults are eating well, cover the bedding with paper toweling so they aren’t tempted to fill up on bits of bedding.

Brooder Bedding Benefits

Good bedding benefits brooding poults in many ways.

• It provides a soft place for the poults to rest.

• By insulating the floor, it keeps the brooder toasty warm.

• It absorbs moisture from droppings and spilled drinking water.

• It keeps poults busy by giving them something to scratch in.

• By getting mixed with droppings it prevents manure caking.

• It allows poults to engage in the natural activity of dusting.

Until they grow a full set of feathers, your poults will need heat. An infrared lamp in a reflector is commonly used to provide heat for small-scale brooders, although an infrared pet heater panel (such as those made by Infratherm) is superior because it is not a fire hazard, can’t burn out and leave your poults without heat, and when they start perching they can’t accidentally knock the panel down.

Since, unlike an infrared lamp, a heater panel does not emit light, if you use that style heater you will need to light the brooding area so the poults can find feed and water. For the first week leave the light on all the time. After a week, change the bulb to a low wattage (dim) light and turn it off for at least one hour every 24 to accustom the poults to darkness so they won’t panic in a power failure.

As a general rule, start with the heat source about 18 inches (46 cm) above the brooder floor and raise it about 2 inches (5 cm) each week until it is 24 inches (61 cm) above the floor. The temperature at poult level should start at 95˚F (35˚C) and be reduced 5˚F (2.7˚C) per week until the brooder temperature is 70˚F (21˚C) or the same as ambient temperature. When the weather is warm, or the poults are well feathered, they no longer need heat. You can judge their comfort level the same way as you would for chicks, illustrated on page 21.

At about 3 weeks of age (4 to 5 weeks for broad breasted strains) your poults will want to perch on anything above the floor—typically on top of the feeder, drinker, or heater. At this point you might install a 2-inch (5-cm) round roost, 12 inches (30 cm) off the floor, to give them something suitable to perch on. Allow 6 inches (15 cm) of roosting space per turkey.

When poults reach the age of three weeks they appreciate a small homemade perch like this one.

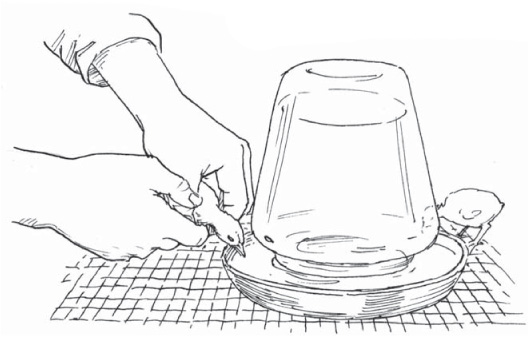

Dip the poult’s beak first in water and then in feed to encourage it to drink and eat.

Turkey poults often need help finding feed and water, so for the first few days keep an eye on them to make sure they all learn to eat. As soon as your poults arrive, give each one a drink of water. Gently pick up the poults one by one and dip their beaks into the drinker. When a poult tips back its head to let the beakful of water slide down its throat, you know it has had a drink. You can then dip its beak into the feeder to show it where to eat, then tuck it under the heater.

Initially sprinkling feed onto a piece of cardboard, a cookie sheet, or the paper towels covering the brooder floor gives the poults something to peck at, and once they start pecking the scattered feed they are likely to look for more feed to peck. You may need to scatter feed several times before they are all eating from the feeders. To attract the poults to the feeders, put a few shiny or brightly colored marbles into the feed, cover the feed with mashed hard-boiled egg, or sprinkle uncooked oatmeal over the feed. When they are all eating from the feeder, remove the cardboard or cookie sheet.

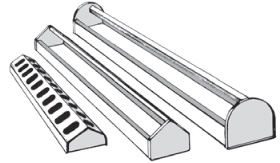

For the first week or so, a chick-size feeder works fine for poults. Later they’ll need something larger, which could be a commercially purchased trough feeder, a homemade wooden trough, or a hanging tube feeder. Furnish enough feeder space so at least half the turkeys can eat at the same time. For 24 poults you’ll need 6 linear feet (1.8 m) of trough space. If the trough is attached to the wall, so they can eat from only one side, you’ll need troughs totaling 6 feet; if they can eat from both sides, you’ll need 3 total feet (0.9 m), such as two 18-inch (46 cm) long troughs. With hanging tube feeders, you’ll need 16 inches (41 cm) total diameter, such as one 16-inch or two 8-inch (20 cm) diameter feeders. Less feed will be spilled if the feeders are adjusted to remain about the height of the poults’ backs as they grow.

Feed your poults free choice, meaning feed should be available to them at all times. To reduce feed waste by scratching and beaking out (using the beak to scoop feed onto the floor), never fill a trough feeder more than half full, and refill it often. Scratching is not possible with a tube feeder, and a proper tube rim has a rolled-in lip to prevent beaking out.

At first your poults will peck a little feed here and there and won’t seem to eat much. By the time they reach 2 weeks of age they could be eating as much as half a pound of feed per bird per week. As they approach harvest weight they may eat as much as a pound (450 g) of feed per bird per day.

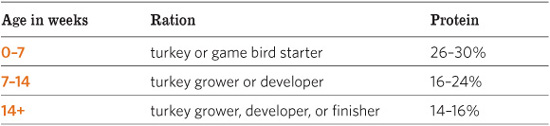

The feed you put into the feeders will depend in good part on what is available locally. In an area where turkeys are commonly raised, turkey starter, grower, developer, and finisher rations may be available. In other areas you’ll need to find reasonable substitutes.

Turkey starter ration, fed for the first seven weeks or so, contains 26 to 30 percent protein. Game bird starter is suitable for turkeys. Another option is to use chick starter (usually 20 to 24 percent protein) and add 4 pounds (1.8 kg) of fish meal (averaging 65 percent protein) per 25-pound (11.3 kg) bag of ration. With this option, when the poults are about 4 weeks old taper the fish meal down to 2 pounds (0.9 kg) per 25-pound bag of ration.

Turkey grower or developer ration, fed from about 7 to 14 weeks, contains 16 to 24 percent protein. Where turkey ration is not available, you can feed the same ration that would be fed to chickens raised as broilers. This ration can be continued until the birds reach harvest weight. Or, where regular turkey rations are available, when the poults reach 14 weeks of age you can switch to turkey finisher, containing 14 to 16 percent protein, and continue until the birds reach harvest weight. If the turkeys are putting on too much fat toward the end, substitute whole oats for 20 percent of their ration (see page 65 on how to assess the fat cover, or finish).

Rodent Control

Rodents can eat an amazing amount of feed, vastly increasing the cost of raising turkeys. Keeping rodents away is not easy, as they are attracted by the ready availability of feed. Store rations in a container with a tight lid, such as a clean trash can, and sweep up any spilled feed. At the first sign of rodents—droppings, tunnel openings, holes chewed in unopened feed sacks—set out traps. Poisoning is another option, but must be done with great care to avoid poisoning the turkeys.

Commercially prepared rations come in the form of pellets or crumbles. Pellets are made from a ground-up mixture that has been compressed. Crumbles are crushed pellets that are fed to poults not yet big enough to swallow whole pellets. Starter ration comes in crumble form. Once your turkeys pass the starter ration stage at about 7 weeks of age, they are big enough to handle pellets.

Three Styles of Feeders

Ready-made trough feeders come in various lengths and diameters.

Homemade wooden trough feeder with feet at both ends to adjust the height as the poults grow.

A hanging tube feeder can be easily raised by means of a chain to keep it at the level of the turkeys’ backs as they grow, thus minimizing wasted feed.

Whenever you change from one ration to another, make the change gradually to avoid digestive upset. Begin by adding a little of the new ration to the one you have been feeding. Each day, for the course of about a week, add a little more until the changeover is complete.

Turkeys love greens, and that goes for poults, too. But until they reach about 6 weeks of age, poults are not ready to forage for themselves. Before then they would appreciate a daily salad consisting of greens finely chopped with a salad chopper or a pair of scissors.

Suitable greens include such things as lettuce, chard, grass clippings from a lawn that has not been sprayed, and tender alfalfa or clover leaves. Another option is to sprout alfalfa or other seeds for them. Just be sure anything you feed your poults is fresh, tender, and chopped small enough for them to eat.

As soon as you introduce greens to your poults, they also need access to clean sand or granite grit to help digest the roughage. For information on granite grit, see page 38.

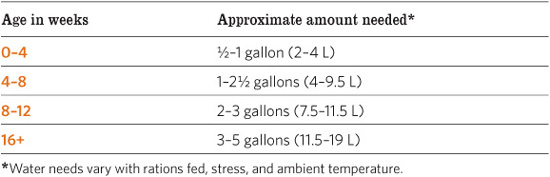

Turkeys must have access to fresh, clean water at all times. Provide enough drinkers so at least one-fourth of your turkeys can drink at the same time. When your poults first arrive, mixing a water-soluble vitamin-mineral electrolyte into their drinking water will help reduce shipping stress. Most hatcheries offer an electrolyte mix and will ship it in the carton with the poults.

Drinkers are made of either plastic or galvanized steel. Plastic eventually cracks, and steel eventually rusts. You can extend the life of your waterers by keeping plastic out of the sun and keeping metal off the ground.

Drinkers come in various sizes from 1 quart (1 L) to several gallons. A 1-gallon (4 L) drinker is sufficient for two dozen poults during their first month. After that you can add more drinkers or use larger ones. A comfortable size for most people to carry is a 2-gallon (7.5 L) model, which weighs 16 pounds (7 kg) when full of water. By the time two dozen turkeys are fully grown you would need three 2-gallon drinkers. A good idea is to always keep an extra drinker on hand in case one springs a leak.

Skin Color

Turkeys naturally have white skin. When turkeys are fed corn or greens (including foraging on pasture) their skin may become yellowish.

Waterers can be set on the floor or hung from a chain. The advantage to using hanging drinkers is that they can easily be raised as your turkeys grow. The disadvantage is that they tend to spill, especially when poults bump into the drinker or try to perch on top and cause the drinker to swing from the chain. Placing bricks, blocks of wood, or concrete blocks underneath to stabilize the drinker will keep it from swinging, while the chain keeps the drinker from being knocked off the blocks.

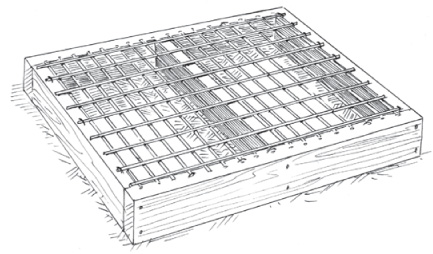

The chief advantage to a floor drinker is that it can be moved around more easily. But floor models tend to get cluttered with bedding, which can be minimized by putting each drinker on a hardware cloth platform built over a sturdy wooden frame. Using platforms for metal drinkers keeps them off the ground and thus delays rusting. Be sure the platform doesn’t place the water too high for young turkeys to reach.

Water Requirements per 24 Turkeys

A drinker hanging from a chain can be easily raised as turkeys grow.

In hot weather, reduce stress by frequently providing cool water to encourage drinking. Check waterers often to ensure your turkeys never run out; for every 20˚F (11°C) increase in temperature, the turkeys’ water needs can as much as double.

At least once a week, or sooner if algae begins to appear, scrub drinkers with a dishwashing brush and detergent, then sanitize them with a solution of chlorine bleach (1 teaspoon [5 mL] of bleach per gallon [3.8 L] of water). Before refilling the drinkers with water, rinse them well to remove all traces of bleach, which can be fatal to poults.

Setting a drinker on a platform such as this one keeps bedding out of the water and delays rusting of a metal model.

Depending on the weather, turkeys can go outside when they are about 6 weeks old. When the temperature reaches 70°F (21°C) or above, and the weather is not inclement, the birds can spend a little time outdoors each day. At 8 weeks of age, they may be allowed to come and go as they please.

You can use one of several different management systems to raise a few turkeys for meat for the family. Which system works best for you will depend in large part on how much land you have available.

Turkeys can be kept indoors for their entire lives. The facility should be large enough so each turkey has at least 6 square feet (0.5 sq m) of living space. The floor should be covered with at least 4 inches (10 cm) of clean, dry, absorbent, dust-free bedding and the litter must be refreshed as often as necessary to eliminate caked manure and wet spots. The building must be well ventilated but not drafty, and it must have enough light for the turkeys to find the drinkers and feed troughs. Under this system, all feed is brought to the turkeys, and in most cases they are fed commercial rations the entire time.

Confinement is most common where predators are numerous, where the weather is always rainy or otherwise bad, or where insufficient space is available to provide a yard or pasture. This system is not ideal for the turkeys, as they never get to enjoy fresh air and sunshine, and if they become bored they may pick on each other. Confinement is most often used for broad breasted strains, which grow rapidly and may be harvested in as little as 16 weeks. It is much less suitable for heritage breeds, which are more active and can take as long as 6 months to reach harvest weight.

A more typical backyard option is to allow turkeys access to a yard during the day. The indoor facility is much the same as for confinement, although it needn’t be quite as large. The same building that was used for brooding the poults can be used to provide shelter for yarded turkeys. One-quarter acre, or about 150 feet by 75 feet (46 m × 23 m), is sufficient for two dozen turkeys. The yard should be protected with woven-wire field fence or chain link.

Yarding has a huge advantage over confinement in that it gives the turkeys an opportunity to spend time in the fresh air and sunshine, and gives them more room to move around and engage in the natural activities of pecking, scratching in the soil, and dust bathing. On the other hand, turkeys that spend more than a couple of months in a yard will soon eat or trample all the vegetation, and the yard will become packed solid (or, in rainy weather, will become a sea of muck).

Raising turkeys on pasture involves providing enough land for the turkeys to forage over that they do not destroy the vegetation, which requires periodically moving the turkeys to new ground. This system is more natural, and therefore healthier, than confinement or yarding, but it requires more land. Two dozen turkeys need at least one-half acre (2,025 sq m) of good pasture, such as alfalfa or ladino clover. By foraging for insects and greens, the turkeys will eat as much as 25 percent less of the commercial ration.

Prevent Flying

The flying breeds like to perch on fences and gates, often coming down on the wrong side and then running up and down the fence trying to get back in with the rest of the gang. Even a fence as high as 6 feet (1.8 m) will not keep in some breeds.

Stringing several strands of smooth wire or a single electrified wire along the top of the fence serves as a deterrent to roosting. A net cover over the entire yard, where feasible, will keep turkeys where they belong. Clipping the flight feathers of one wing puts a bird off balance so it can’t fly but lasts only until new feathers grow in. Clipping off the first joint of one wing of newly hatched poults is a drastic but surefire method of permanently preventing flight.

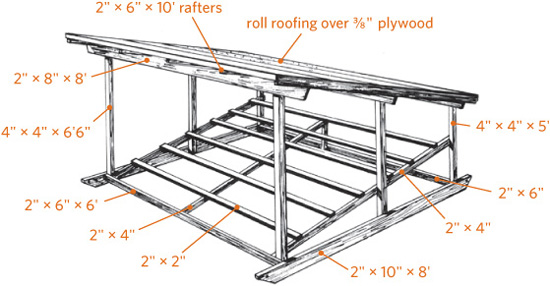

Portable range shelter on skids.

One method of pasturing turkeys is basically an extension of yarding, except that it involves multiple yards. Situate the shelter in the center of the pasture and divide the pasture into paddocks, or pens, that radiate out from the shelter like spokes of a wheel and let the turkeys into each pen sequentially. When one pen has been grazed down, or if bare spots appear, move them to the next pen.

How long a flock takes to graze down a given area depends on a number of factors, including the size of the flock, the kind and condition of the pasture, temperature, and rainfall. When sun, rain, and warm weather combine to help plants grow quickly, your flock can graze a given area for two weeks or more. In cool, hot, or dry weather, when plants grow slowly, the same number of turkeys may graze down the same area to nothing in a matter of days. The best

you can do is keep a watchful eye on the vegetation and move the turkeys when they have grazed the plants down to 1 inch (2.5 cm), or when bare spots begin to appear.

Meanwhile, vegetation in other pens must not be allowed to grow taller than about 5 inches (12.5 cm), so during times of rapid vegetative growth you will have to mow unused pens. Bear this fact in mind when installing fences so you can avoid odd corners where your mower cannot reach; otherwise you’ll have a lot of extra work removing weeds that grow out of control in the unreachable corners. For a typical rotation plan see page 31.

A more healthful method of pasturing, but one that involves more work, is to use a portable range shelter and move it to fresh ground at least once a week. Between times, move the feeder and drinker every day to spread droppings and reduce trampling of the vegetation. During times of rapid vegetative growth, keep the pasture mowed to no taller than 5 inches (13 cm).

Pasture Confinement

A pasturing alternative that gets wide press is to confine poults within a range shelter that is moved daily. The shelter provides 4 square feet (0.4 sq m) per turkey, or 10 feet by 10 feet (3 × 3 m) for two dozen birds (12 feet by 12 feet [3.5 × 3.5 m] if they are broad breasted). Since the poults never leave the shelter, feeders and drinkers must be contained within the shelter. Each morning without fail the shelter must be moved to new ground, as the turkeys will voraciously eat down the fresh vegetation during the day and foul the ground overnight.

Pasture confinement was originally designed for raising broilers, which take about eight weeks to grow to harvest weight. Turkeys, on the other hand, take four to six months to grow out, vastly increasing the climatic variety the poults must endure, the amount of land required, and the amount of work involved in continually moving the pasture shelter. More information can be found on the Internet by doing a keyword search for “pastured poultry” and for “pastured turkeys.”

A homemade range trough feeder with a hinged roof to keep out rain.

The range shelter should provide at least 2 square feet (0.2 sq m) per turkey, or about 6 feet by 8 feet (1.8 × 2.5 m) for two dozen birds. Roosts must be sturdily built to support the aggregate weight of the growing turkeys. Allow a minimum of 15 inches (38 cm) of roosting space for large breeds and 12 inches (30 cm) for smaller breeds. The roosts can be made from 2 × 4s, with the edges rounded, oriented narrow side up and spaced 18 inches (46 cm) apart if they are slanted ladder fashion, or 24 inches (61 cm) apart and 15 to 30 inches (38 to 76 cm) off the ground if the roosts are arranged platform-style.

Turkeys can be pastured from the age of 8 weeks until they reach harvest weight. Pasturing is more suitable for the active heritage breeds than for the more lethargic broad breasted strains, although people have successfully raised both types on pasture.

Growing turkeys have sharp claws that can easily wound your flesh, and powerful wings that can cause bruising or even a black eye if the turkey flails at you. Catching and carrying a turkey must therefore be done with caution.

If you need to move a group of turkeys, sometimes the easiest method is to drive them. Unlike chickens, turkeys can be herded like cattle, which is handy when the time comes to move them from the brooder to pasture, for instance, or when you want to load them to take to the slaughterhouse. To control and guide the turkeys, a stick comes in handy. It should be several feet long and have a piece of survey tape or a strip of cloth tied to one end to get their attention.

The turkeys will travel together as a group. Guide them with the stick in the direction you want them to go. Move slowly and don’t chase them. If they get rushed or otherwise frightened—such as being pushed too rapidly toward something they are unfamiliar with—they may panic and stampede, causing them to crash into a fence or a building and trample or smother each other.

If you need to catch a turkey, you will cause less confusion and incur less chance of injury to yourself or the turkey if you do it in a darkened area. The best time to catch turkeys is at night, after they have gone to roost. Having a helper comes in handy, to briefly turn on a flashlight while you locate the turkey you want to catch.

For a young or small turkey, grasp both legs in one hand and cradle the breast with the other arm. For an older or heavier turkey, take one leg in each hand, then transfer both legs to one hand and clasp the bird against you with its rear pressed against your body, then reach around and get hold of the wing on the far side, where it attaches to the turkey’s body. With the legs and wings immobile, the turkey is less apt to struggle.

The list of diseases turkeys are susceptible to is long enough to discourage anyone from trying to raise a turkey. But if you start with healthy poults, keep them in a clean environment, and feed them a healthful, nutritious diet with plenty of fresh, clean drinking water, you shouldn’t experience a disease outbreak.

A dead poult is, of course, a sign of disease, but don’t panic if one bird dies. Poults need time to build up their immune systems, and until they are about 3 months old they can be pretty vulnerable. The average mortality rate for young turkeys raised commercially is about 15 percent, and some growers do much worse. Naturally you’ll be upset when you find a dead bird, but it’s not a major issue unless several die at once or show other signs of disease. Should the latter occur, isolate the sick poults and seek help from someone experienced with turkeys, an avian veterinarian, or your county Extension agent. The most common health concerns among backyard poults are blackhead, cannibalism, coccidiosis, and predation.

When you are familiar with how a healthy poult looks and acts, you can easily detect illness by noticing changes. Each time you visit your poults, stand quietly for a few moments and watch for anything unusual.

Sound. Healthy poults make pleasant, melodious sounds. Sick birds may sneeze or make other abnormal sounds.

Smell. Notice how your poults normally smell. Any change in odor is a bad sign.

Appearance. A healthy poult looks sharp and perky. A sick poult may become droopy and inactive, pull in its neck, appear sleepy, and let its feathers hang loosely.

Droppings. The droppings of a tom differ from those of a hen. The tom’s droppings are cylindrical in shape, blunt at the ends, and arranged like a J, L, question mark, or sometimes a straight line with white urates (the equivalent of turkey urine) at one end. The hen’s droppings are slightly smaller in diameter and fall into a roundish pile of loops or spirals with white urates on top or to one side. For both genders, the droppings are firm, although occasional thick, sticky droppings are also normal. Abnormal droppings may be soft, watery, or bloody.

A tom’s droppings are cylindrical and often J-shaped (right); a hen’s droppings make a rounder pile (left).

Behavior. Notice the amount of feed your poults normally eat and the amount of water they drink. Unhealthy poults may drink more than usual, eat or drink less than usual, and may stop growing.

Histomoniasis is a serious disease of turkeys caused by Histomonas meleagridis protozoa, which live in most poultry environments, except where the soil is dry, loose, and sandy. The disease is commonly known as blackhead, which is misleading because the head of an affected bird does not always darken.

The protozoa lodge in blind intestinal pouches or ceca, enter the bloodstream, and eventually migrate to the liver. Early signs of the disease include droopiness, diarrhea, yellow droppings, and weight loss. Sometimes reduction of oxygen in the blood causes the skin to appear dark blue or black, leading to the name blackhead. Damaged tissue in the ceca may result in bloody droppings that might be mistaken for coccidiosis. Turkeys die from either liver failure or a bacterial infection following damage caused by the protozoa; sometimes dead turkeys are the first sign of this disease.

The protozoa are carried by the cecal worm (Heterakis gallinarum), the most common parasitic worm in North American poultry. The infection is spread by cecal worms and their eggs that are expelled in droppings and then picked up by a foraging turkey. Earthworms, too, may eat infected cecal worm eggs, and then infect a turkey that eats the earthworms.

Protozoa that lack the protection of a cecal worm egg quickly die, but given such protection can survive in the environment for years. Once a flock becomes infected, blackhead is difficult to eliminate from the flock or the land. Prevention is therefore a preferable plan, and starts by helping the poults develop a strong immune system; see “Strengthening Immunity” on page 63.

A sure way to prevent blackhead is to keep young turkeys away from older turkeys and chickens, and avoid raising turkeys on land where any poultry have lived for at least three years. The time period can be shortened to two years if the land is rototilled and gardened before being returned to pasture. During the rearing period, pasture rotation helps prevent a buildup of infectious organisms, as does periodically moving feeders, drinkers, and roosts.

Poults that pull each other’s feathers or peck each other’s flesh are unhappy, mismanaged birds. Cannibalistic behavior is more common among commercial turkey strains raised in industrial confinement than among standard breeds kept in a typical backyard setting. Conditions that encourage cannibalism are overcrowding, keeping the brooder temperature too high, and letting feeders go empty.

Poults raised on slats or wire, or in confinement, are more likely to pick on each other than poults in a yard or on pasture, where boredom is less likely. Cannibalism can be deterred by giving the turkeys something to do: Provide a bin of loose soil for dust bathing; set out a bale of hay for them to hop up on and peck at; suspend a flake of hay or a fresh head of cabbage or lettuce where they must reach up to peck it; hang a few shiny pie tins so they can amuse themselves pecking.

How Long Does a Turkey Live?

The vast majority of domestic turkeys live only a few months before they land on a serving platter. The industrially bred toms and hens that produce those turkeys are slaughtered before the age of 2. Standard, or heritage, turkeys raised on pasture have a longer productive life; toms typically breed for 3 to 5 years, hens for 5 to 7 years. The average lifespan of a domesticated turkey is 10 years, although some may live to the ripe old age of 15.

Turkeys and Chickens Together?

Conventional wisdom says you should never keep turkeys and chickens together because turkeys are susceptible to blackhead, a disease with devastating consequences. However, lots of backyarders raise chickens and turkeys together without a problem, and with some benefits.

Newly hatched poults tend to get off to a slow start, but chicks are somewhat quicker on the uptake. Poults brooded with chicks learn to eat and drink more readily by following the chicks.

Broody chickens are often used to hatch turkey eggs. A medium-size chicken can handle about half a dozen turkey eggs. Soon after the eggs hatch, most broody hens will accept six or so additional poults slipped in with the ones she hatched.

Chickens raised with turkeys acquire a sort of immunity to Marek’s disease. Turkeys carry a related, although harmless, virus that keeps the Marek’s virus from causing tumors in chickens.

On the downside, young turkeys need considerably more protein than baby chicks. And as they grow, chickens are attracted to a tom turkey’s tail display, and may follow the tom, picking feathers from his rear end. If not stopped—by separating the offending chicken(s) from the tom—the situation can turn bloody.

And, of course, there’s the blackhead issue. Although chickens commonly carry the blackhead protozoa without being infected, turkeys—especially young ones—are highly susceptible and can easily get infected by chickens. Since an outbreak of blackhead requires the presence of both histomonads and cecal worms, the danger of blackhead can be minimized by not bringing in new poultry that may bring trouble with them and, where cecal worms are already present, by regular deworming to reduce the cecal worm population.

A chicken hen will brood at least twice as many poults as she can hatch.

Most importantly, give your turkeys plenty of room to grow. At the first sign of pecking, increase their living space, preferably by moving them to different housing, or, best of all, putting them on pasture if they are old enough and the weather is nice enough.

Like chicks, poults are susceptible to coccidiosis—an infection caused by parasitic protozoa—but the protozoa that affect chickens are not the same as those affecting turkeys, and vice versa. So chickens cannot transmit coccidiosis to turkeys, and turkeys cannot transmit it to chickens.

Coccidiosis infects poults before they have had a chance to build up an immunity, which occurs through gradual exposure to protozoa in the environment as the poults grow. Too-rapid exposure, by way of infected droppings, results in an outbreak of coccidiosis. Affected poults sit hunched up with ruffled feathers and their heads pulled back, may have bloody diarrhea, and, left untreated, may die. Poults that have been infected and then treated likely will not grow well.

Poults housed on a slat or wire floor, where their droppings can fall through, are less likely to be infected than turkeys kept on litter or pasture, where droppings may accumulate. However, raising turkeys on a slat or wire floor does not allow gradual exposure to the protozoa and therefore may only delay an outbreak of coccidiosis; furthermore, it can also lead to other problems including lameness and cannibalism.

The best preventive measure is good management. Keep feeders and drinkers free of droppings, manage litter to prevent damp spots and manure caking, and move pastured poults often enough that they don’t have to forage in accumulated droppings.

As a first-time turkey owner, you would be wise to avoid coccidiosis by feeding your poults a medicated turkey starter, which contains a coccidiostat. Medicated starter is a preventive measure and won’t help birds that already have coccidiosis. Treating the disease requires stronger medication available from a farm store, poultry supplier, or veterinarian.

You can help your poults develop strong immune systems using a probiotic and a vitamin/mineral mix for their first three months of life. The simplest option is to use a product such as Vita-Pro-B Concentrate containing vitamins, minerals, electrolytes, and a probiotic all in one, and mixing it into the drinking water according to directions.

Another form of probiotic is a live culture yogurt, which can be purchased at the market or made at home using a yogurt maker and starter culture. For two dozen poults, evenly stir ½ cup (120 mL) of yogurt into 1 quart (1 L) of starter crumbles. Feed this mix first thing in the morning, and when it’s gone refill the feeder with plain crumbles for the rest of the day.

If you use yogurt as your probiotic, you’ll also need a water-soluble vitamin/mineral mix—available from a poultry supplier, farm store, and some hatcheries—to dissolve in your poults’ drinking water. Broiler Booster brand is formulated for turkeys and other meat birds. If you opt for a standard poultry mix, double the recommended dose for the first month, then reduce to the regular amount.

Predators abound that like to eat turkey as much as you do. The type of predators most likely to visit your turkeys depends on where you live, how populated the area is, and how secure your turkeys are. Predators can be loosely divided into three groups, as defined by the turkeys’ age and the system under which they are managed.

Predators affecting young, confined poults. They include rats, snakes, and weasels. These predators are the most difficult to control because they can squeeze through a hole so small you might not notice it. Watch for small gaps in housing and holes or tunnels coming through the floor, particularly in corners and along the walls.

Predators affecting yarded poults. They are likely to fly in—eagles, hawks, and owls—and therefore cannot be deterred by the stoutest fence. Since owls hunt at night, you can protect your turkeys by closing them in at night. Eagles and hawks, however, hunt in the daytime. They can be kept away from yarded poults by covering the yard with netting or by crisscrossing the yard with wire filament and hanging something that spins or flutters when a raptor flies near; old CDs and DVDs are ideal for this purpose, but strips of fabric such as old bedsheets also work.

When a raptor comes to land in the chicken yard and stirs up a breeze with its wings, CDs and DVDs will spin (or fabric strips will flutter) and scare it away.

Predators affecting pastured turkeys, including both raptors and four-legged hunters such as coyotes, dogs, foxes, and raccoons. A strong perimeter fence, preferably electric, is a good start toward keeping them out, and a second fence within the perimeter fence is even better. Since most four-legged predators prowl at night, enclosing your turkeys in a well-built range shelter overnight will protect them should a predator get through the fence(s). Solar operated Nite Guard flashing lights are also effective when used as directed by the manufacturer.

Once a predator gets a taste of turkey, keeping it away from the flock becomes more difficult. So keep an eye out for predators and their signs (scat, tracks, and sometimes scent), patrol your turkey facility often looking for security breaches, and take corrective measures as necessary. Information on predators common in your area, and their signs, is available from your local wildlife office and county Extension office.

Helpful guides to identifying predators include Scats and Tracks of North America by James C. Halfpenny, PhD, and The Encyclopedia of Tracks and Scats by Len McDougall.

In 16 to 20 weeks for broad breasted strains, and 24 to 28 weeks for standard breeds, your turkeys will be ready to harvest. The industrial strains have a high meat-to-bone ratio, finish with little fat, and are relatively free of pinfeathers. The standard breeds are a little less meaty and are harvested when nearly mature.

At the age of 22 weeks they will begin storing a layer of fat, which by nature is intended to help them survive the lean winter months. The flavor is in the fat, which is one reason heritage breeds are tastier than industrial strains. The fat layer under the skin also makes heritage breeds self-basting while they roast.

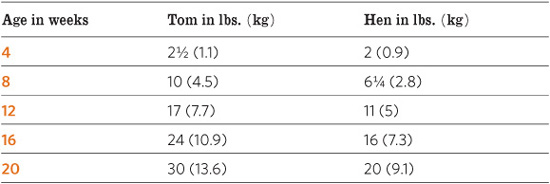

By weighing a few turkeys every four weeks, you can track their growth rate and determine if they are on target. Remember that heritage breeds gain weight more slowly than industrial strains, and a turkey on pasture will gain weight more slowly than the same turkey kept in confinement.

The table on page 65 indicates typical weight gains for industrial strains. Establishing a similar table for heritage breeds would be difficult because they have not been selectively bred for uniformity of growth and size. However, by tracking your turkeys’ weights you will determine if they are gaining at a steady and satisfactory rate.

Weighing your turkeys also helps you determine when they are approaching harvest weight, depending on whether you prefer a smaller turkey or a larger turkey. You might butcher some at a lighter weight and let the rest grow, for instance harvesting smaller turkeys for Thanksgiving and growing larger ones for Christmas. Be aware, however, that the feed conversion rate goes down as the weight goes up, so the more your turkeys weigh at harvest, the more they cost per pound to raise.

Keep in mind that a turkey’s weight is not all meat. A turkey that weighs 20 pounds at the time of butchering, for example, will not yield 20 pounds of meat. Broad breasted hybrid turkeys dress out to approximately 80 percent of their live weight. Heritage breeds dress out to approximately 75 percent of their live weight. For both, hens typically dress to a slightly lower percentage of live weight than toms.

In a highly controlled industrial confinement setting, the average feed conversion rate for broad-breasted hybrids is 2.5 to 1, meaning for every 2.5 pounds of feed a turkey eats, it gains 1 pound of weight. If you raise a broad breasted strain at home, you can’t hope to achieve much better than 3 or 3¼ to 1. So a turkey that weighs 16 pounds at harvest will have consumed approximately 50 pounds of feed.

Feed conversion rates start out low and go up as a turkey ages. The closer the turkey comes to reaching its mature weight, the higher its feed conversion rate. Most industrially raised hens are harvested at about 16 weeks of age at the weight of about 16 pounds (7 kg) live or 12 pounds (5.5 kg) dressed.

Versatile Meat

Although turkey is traditionally served at Thanksgiving and Christmas, there’s no reason you can’t enjoy your homegrown turkeys year-round. The versatile meat can be ground and served like hamburger, made into sausage, sliced as cold cuts, chopped into stir-fry, or served any way you might prepare chicken or pork.

Average Growth Rate of Industrial Turkey Strains

Toms are generally harvested at about 18 weeks of age at a weight of about 28 pounds (13 kg) live or 22 pounds (10 kg) dressed. If you prefer a smaller turkey, either gender can be butchered at the live weight of as little as 10 pounds (4.5 kg) and still yield a respectable amount of meat.

The feed conversion rate for standard, or heritage, breeds varies considerably with breed and strain. Furthermore, heritage breeds are generally raised on pasture, which automatically increases their feed conversion rate, which can range anywhere from 4.75 to 1, to more than 6 to 1. On the other hand, an industrial strain raised under the same system will have a similar conversion rate. The bottom line is that industrial and heritage turkeys raised on pasture will eat approximately the same amount of feed to reach approximately the same weight, because the hybrid eats more but the heritage eats longer. At a feed conversion rate of 5 to 1, a 16 pound (7 kg) turkey will consume 80 pounds (36.5 kg) of ration.

In addition to a turkey’s weight, two other factors determine when the turkey is ready for harvest—minimal pinfeathers and adequate fat cover, or finish. Exactly when those three things come together depends on the turkeys’ breed and strain, as well as a variety of management factors. As your turkeys grow close to the weight at which you wish to harvest them, start keeping an eye on their pinfeathers and finish.

Pinfeathers are immature feathers emerging from the skin. After a poult acquires its first set of feathers, it almost immediately begins to molt, or gradually lose the old feathers as new ones grow in. Generally by the age of 10 weeks or so this molt is complete enough that pinfeathers are not a problem. However, the poult goes through another molt, which overlaps with the previous molt and lasts until the bird reaches about 14 weeks of age. To top things off, a poult then goes through a partial winter molt. With each molt, whenever an old feather falls out, a pinfeather appears in its place.

Pinfeathers are difficult to remove, and unless they are white they appear as dark spots all over the turkey’s skin. When the turkey is roasted whole with the skin on, the pinfeathers can look decidedly unappetizing. By checking the skin beneath the main feathers of the back and breast, you can determine whether or not the turkey is loaded with pinfeathers. Of course, if you plan to skin the turkey before it’s cooked or served, pinfeathers are irrelevant.

Finish refers to a thin layer of fat beneath a turkey’s skin. A turkey without good finish will cook up dry and somewhat tasteless, since fat is where the flavor is. To assess finish, locate the thinly feathered area on the turkey’s breast, about halfway between the breastbone and the wing attachment.

If necessary, pull a couple of feathers so you can get a good view of the skin. A turkey with little fat will appear to have papery-thin, almost transparent skin that looks reddish or bluish purple, because the muscle shows through the skin. A turkey with a good layer of fat covering the muscle will have creamy white or yellowish skin.

Gently pinch the skin between your thumb and forefinger. The pinched skin will be thin on a turkey with little fat, and quite thick on a properly fattened turkey. If you are growing your turkeys on the large side, toward harvesttime they may put on more fat that is desirable. If your turkeys seem to be putting on too much fat, as determined by the pinch test, adjust their diet by substituting whole oats for 20 percent of the ration.

The meat of a wild turkey is almost all dark and has an intense flavor. The meat of a supermarket turkey is mostly white and lacks flavor. A standard turkey raised on pasture lies somewhere between the two—it has more white meat than a wild turkey and better flavor than a supermarket turkey. Why is that?

A turkey uses breast muscles for flying and leg muscles for walking. Wild turkeys actively fly as well as walk while foraging. Industrially raised turkeys don’t fly and in fact can barely walk—their legs are too thin and weak for their heavy bodies. Heritage turkeys raised on pasture spend a lot of time foraging and, given the opportunity, may fly. Active muscles of the legs and breast require oxygen, and oxygen is carried in blood cells. The more active the muscles, the more blood they need, and the more blood they need, the darker the meat.

Muscles get energy from fat stored within the muscle cells. The more the muscles are exercised, the more energy they need, so the more fat they store. A wild turkey that exercises its breast and leg muscles equally has more fat in its muscles than an industrial turkey that never flies and scarcely walks. Since flavor is in the fat, the meat of a wild turkey has more flavor than a supermarket turkey. Similarly, heritage turkeys are more active than supermarket turkeys and therefore more flavorful, but they are not as active as wild turkeys and therefore not as intensely flavored.

Can you save money growing your own turkeys? That depends on a lot of factors, including whether you raise broad breasted or heritage poults, whether you feed them in confinement or on pasture, and whether you are satisfied buying supermarket turkeys or are paying a premium for pastured turkeys. Let’s look at some facts. The cost of purchasing heritage poults is about 60 percent higher than for broad breasted poults. On the other hand, the survival rate of heritage poults can be quite a bit higher than for broad breasted poults.

Using averages (and for simplicity’s sake, ignoring the cost of housing, water, electricity, and so forth) do the math: Let’s say you purchase two dozen heritage poults for $8.00 each and 80 percent of them survive; your effective cost per poult is $10.10. You raise each poult to 16 pounds live weight, or 12 pounds dressed, during which time it will have consumed about 80 pounds of ration. At the current rate of 30 cents per pound, the total cost of feed per turkey comes to $24. Added to the $10.10 initial cost it comes to $30.10 for 12 pounds of turkey, or about $2.50 per pound. The price of supermarket turkeys is about $1.00 per pound; the price of pastured turkeys ranges upward from $4.00 to $6.00 per pound. So your homegrown turkeys will cost more than twice as much as supermarket turkeys, but will be as flavorful as commercially grown pastured turkeys at a cost savings of at least $1.50 per pound.

In some areas, custom slaughterhouses will handle the entire process of butchering, dressing, wrapping, and freezing your homegrown turkeys for you. For step-by-step details on how to slaughter, dress, and store your turkeys yourself see Storey’s Guide to Raising Turkeys by Leonard S. Mercia.

So now that you’ve had so much fun raising your first turkeys, you’re thinking of keeping your best tom and a few of your hens to raise your own poults next year and are wondering what’s involved. First off, if your turkeys are broad breasted, don’t even think about it. They are too heavy and awkward to breed naturally, so they must be bred by artificial insemination. But if you opted for one of the heritage breeds, you’re in business.

Here are the chief advantages of raising your own: They are beautiful in the yard and fun to have around, and with proper management the poults generally have a better survival rate than poults purchased by mail order. Some disadvantages: you’ll be feeding mature turkeys year-round (see chart at right to estimate how much they’ll eat); the hens don’t lay many eggs (expect somewhere between 35 and 100, depending on the breed and strain); mature toms can get aggressive; not all hens have the instinct to brood, and among those that do, not all make good mothers.

Turkeys have not been selectively bred for their mothering instinct, so over time the natural inclination of wild turkeys to raise young has been bred out of our domestic turkeys. Among the breeds that retain the strongest mothering instinct are the Black, Bourbon Red, and Narragansett. For others, and even for some individuals among these breeds, you may need an incubator to be successful in hatching poults. Also, once a hen starts setting she stops laying, so to maximize the number of poults you get each spring you’ll need an incubator.

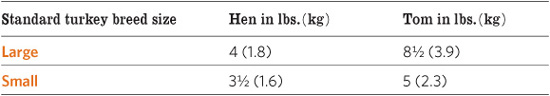

Approximate Feed per Week per Breeder

If you like a challenge, you might try to breed the mothering instinct back into your heritage hens by actively encouraging them to hatch their own eggs. The more hens you have, and the more places you provide for them to nest, the better your chances are of success. One tom can handle between two and six hens.

Breeding turkeys need more space than brooded poults. The shelter should provide at least 8 square feet (0.75 sq m) per bird for a large breed or 6 square feet (0.5 sq m) per bird for a smaller breed. The shelter will need nests for the hens to lay their eggs in. Figure on one nest for up to four hens. A nest that measures 18 inches (46 cm) wide by 24 inches (61 cm) deep by 24 inches high is a suitable size for all breeds. Outdoor space should provide at least 5 square feet (0.5 sq m) for yarded turkeys or 150 square feet (14 sq m) for pastured turkeys. For details on managing a breeding flock of turkeys see Storey’s Guide to Raising Turkeys by Leonard S. Mercia.

Turkey Eggs

A turkey hen lays best during her first year, after which she lays about 20 percent fewer eggs each year. A turkey egg is about twice the size of a chicken egg, and has a huge golden orange yolk. The shell is a pale creamy tan color speckled with dark brown spots. Fertile eggs take 28 days to hatch, which is one week longer than for chicken eggs. You can eat unfertile eggs, just as you would chicken eggs.

Turkeys, like chickens, enjoy dust bathing to condition their feathers and rid themselves of external parasites. Poults go through the motions even when they are brooded on slats or wire without access to a dusting wallow. To take an honest-to-goodness dust bath, the turkey finds a spot of loose soil or litter with which to cover its body, then flaps its wings and kicks its feet to work it through the feathers before shaking it off. In addition to dust bathing, turkeys like to sunbathe, and one can look quite dead lying on the ground with a wing and a leg stretched out to catch the rays.

A tom turkey looks pretty much like a hen until he fans out his tail, puffs out his chest, gobbles loudly, and struts his stuff. While he’s all puffed up, the strutting tom will glide in a semicircle, and when he’s really wound up will make two sounds in succession that are interpreted as “chum” and “humm.” On rare occasions a hen will strut, too, especially when she feels threatened while raising a brood of poults.

Some breeding toms can be aggressive, but don’t mistake curiosity for aggression. A big turkey sidling up to you to find out what you’re up to, or following you to see if you’ve brought a treat, can be intimidating if you aren’t acquainted with the bird in question. A tom that challenges or attacks you has not been taught from a young age that you are the dominant turkey. At the first sign of a problem, be bold, stand up to the turkey, and drive him off rather than running away, but don’t strike the turkey or you’ll only provoke a fight.

Turkeys make a lot of interesting sounds—at least 20 different words have been identified in turkey talk—the most widely recognized of which is the tom’s gobble. Hens never gobble, which is why toms are sometimes called gobblers. You can almost always get a tom to gobble by imitating a gobble. Turkey gobbling is similar in function to a rooster’s crowing, the purpose being twofold: to attract hens and put competing toms on notice. Strutting, too, is intended to assert dominance and attract hens. A tom will generally strut in the presence of a female, but if no female is handy he might strut for any inanimate object that catches his fancy.

Why Is a Turkey a Turkey?

If the turkey is indigenous to North America, and not Turkey, why is it called a turkey? All sorts of explanations have been theorized. One is that the name sounds like the call a turkey makes when frightened: “turk, turk, turk, turk.” Another is that a Native American word for the bird is firkee, which early settlers heard as turkey.

Yet another explanation is that Christopher Columbus, on his expeditionary voyage to discover a northwest passage between India and China, saw wild turkeys when he landed in America. Because the male turkey, like a male peacock, displays his colorful tail to attract a mate, and because peacocks are indigenous to India, Columbus called turkeys by the Indian word tuka, meaning peacock.

Probably the most likely explanation is that it was a simple case of mistaken identity. Early settlers thought the turkey was a type of guinea fowl, which in those days was called a turkey cock because the guinea was introduced into Europe by way of Turkey. Even today people who are unfamiliar with guineas often believe they are some kind of turkey. So, although eventually it became apparent that guineas and turkeys are only distantly related, the die was cast and the turkey remained a turkey.