Keeping ducks and geese is a relatively simple proposition. They require little by way of housing; in a temperate climate, a fence to protect them from wildlife and marauding neighborhood pets and to keep them from waddling far afield will suffice. They prefer to forage for much of their own food. They are resistant to parasites and diseases. In short, they are the easiest to raise of all domestic poultry.

So why doesn’t everyone have waterfowl? Well, for one thing, they like to have at least a small pond to splash in to help them stay clean. Their quacking and honking can get annoying, especially to neighbors. And, while ducks are basically gentle, geese can be decidedly aggressive. But any downside becomes irrelevant if your purpose is to raise a few ducks or geese for roasting or sausage making. Besides, many keepers of ducks or geese enjoy listening to the sounds their birds make, and aggressive geese make terrific watch birds.

Waterfowl Families ................................................................. 70

Waterfowl Traits ........................................................................ 71

Choosing the Right Breed .................................................... 72

Ducklings & Goslings .............................................................. 79

Ducks & Geese for Meat ........................................................ 83

Duck & Goose Egg ..................................................................... 85

Housing a Bevy or Gaggle ..................................................... 88

Feeding Ducks & Geese ......................................................... 92

Duck & Goose Health .............................................................. 99

Managing Ducks & Geese .................................................. 100

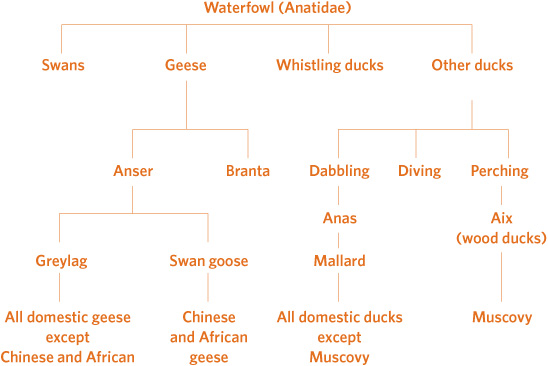

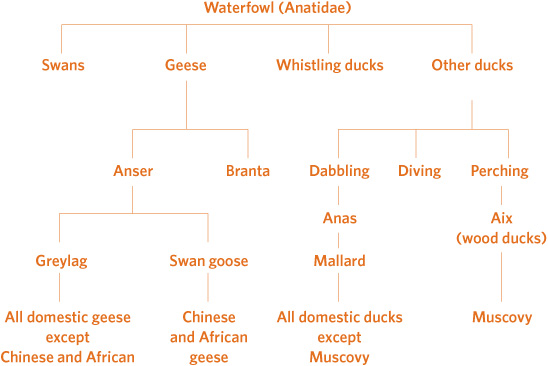

The word waterfowl collectively refers to birds in the Anatidae family—ducks, geese, and swans. The Anatidae family comprises more than 140 species, all of which are web-footed swimming birds that have a row of toothlike serrations along the edges of their bills (which allows them to strain food out of water).

Waterfowl fall into two basic sub-families. On one side are geese, along with swans and whistling ducks. These fowl share many common characteristics. Males and females have the same color pattern and a similar voice, molt annually, and mate permanently. The males in this group help incubate and care for the offspring. Being large birds, geese and swans have a hard time hiding while on the nest; thus, to protect themselves, they are instinctively aggressive. They nest after laying only a few eggs, and their hatchlings mature slowly. This group includes the 14 species of goose, which are classified into two groups. One of those groups includes the two species from which domestic geese were developed—the swan goose, which gave us African and Chinese geese, and the graylag, which gave us all other domestic breeds.

The second basic subfamily of waterfowl includes all ducks except the whistlers. The shared characteristics of these ducks are that males and females differ in color pattern and voice, molt twice a year, and mate for a single season. When the female starts nesting, the male moves off by himself. These ducks are smaller than the birds in the first subfamily and can hide themselves more easily. They hatch more eggs at a time, and their hatchlings mature more quickly. This subfamily includes three groups: diving ducks, dabbling or surface-feeding ducks, and perching or wood ducks. The Muscovy was derived from the perching ducks. All other domestic ducks were derived from the Mallard, which is one of the 11 species in the dabbling group.

Waterfowl Family Tree

Terminology

Talking about waterfowl can get a bit confusing. A male duck is a drake, but a female duck is a duck. A male goose is a gander, but a female goose is a goose. So a drake is a duck, but a duck isn’t always a drake, and a gander is a goose, but a goose isn’t always a gander. Got it? Thanks to this confusion, a female duck or goose is typically called a hen.

Dealing with these fowl in groups is much simpler: A bunch of ducks is a bevy, and a gang of geese is a gaggle.

A hatchling is a duck or goose fresh out of the egg. If the hatchling is a duck, it is a duckling; if it is a goose, it is a gosling. A hatchling that survives the first few critical days of life and begins growing feathers is called started. When it goes into its first molt (shedding of feathers), it’s called junior or green. Until the bird reaches 1 year of age, it’s young; after that, it’s old.

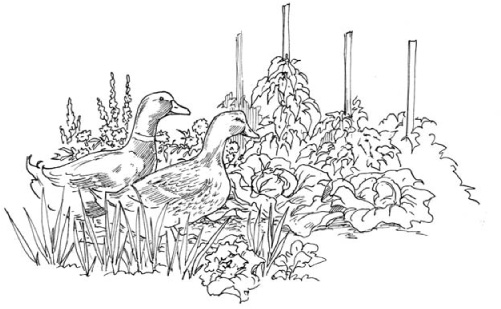

Ducks spend a lot of time in water, nibbling at plants, bugs, and other shoreline inhabitants. If you let them wander in your vegetable garden or flower bed, they will help control garden pests, although you have to take care they don’t run out of other things to eat and start in on your pea vines or pansies.

Muscovies in particular relish slugs, snails, and other crawly things. In fact, the San Francisco area once had a rent-a-duck service that loaned out Muscovies to local gardeners. Ducks also enjoy chasing flies, in the process offering not only fly control but also endless entertainment. Ducks keep mosquitoes from getting beyond the larval stage, but unfortunately tadpoles suffer the same fate.

All ducks lay eggs, although some breeds lay more than others. Khaki Campbells are particularly known for their laying ability, and their eggs make wonderful baked goods. Any breed can be raised for meat, and putting your excess ducks into the freezer both keeps meat on your family table and keeps down the population at the pond.

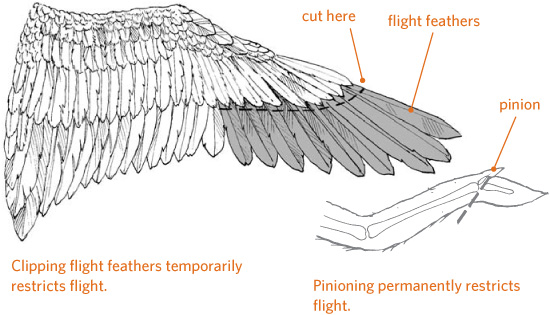

Some breeds like to fly around, and occasionally one will fly off into the sunset, but such wanderlust can readily be controlled by clipping a wing or better yet, if your duck yard is small enough, covering it. The primary downside to ducks is their eternal quacking. In a neighborhood where the noise could become a nuisance, the answer is to keep Muscovies, also known as quackless ducks. Among the other breeds, the male makes little sound, but the female quacks loudly, and each bevy seems to appoint one particularly loud spokes-duck to make all the announcements.

Geese also make a racket with their honking. Usually they holler only with good reason, but a less observant human might not detect that reason: for instance, a cat or weasel the geese have spotted slinking along the fence line. Besides announcing intruders, geese have a tendency to run them off. A lot of people are more afraid of geese than of dogs, probably because they are less familiar with geese and feel intimidated by their flat-footed body charge, indignant feather ruffling, and snakelike hissing. Even as they fend off intruders, geese can become attached to their owners and are less likely to charge the family dog or cat than roaming pets and wildlife.

Geese are active grazers, preferring to glean much of their own sustenance from growing vegetation. They are often used as economical weeders for certain commercial crops; farmers take advantage of their propensity to favor tender shoots over established plants.

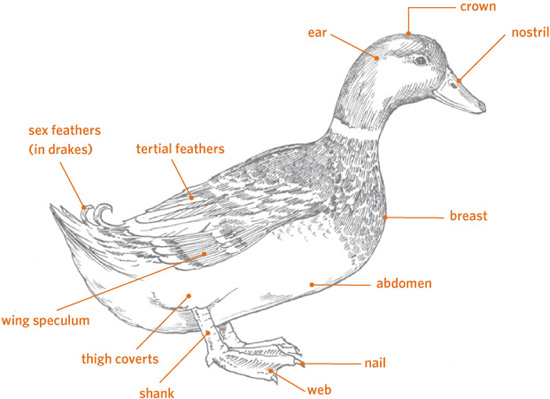

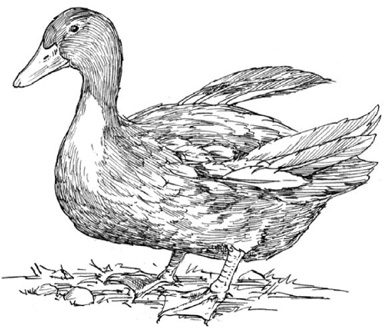

Parts of a duck (or goose)

Geese lay enough eggs to reproduce, but no breed lays as many eggs as the laying breeds of duck. Goose meat, however, is plentiful and delicious. Goose is a traditional holiday meal, and when roasted correctly, the meat defies its reputation for being greasy. Goose fat rendered in the roasting makes terrific shortening for baking (leaving your guests wondering what your secret ingredient might be) and in the old days was used as a flavorful replacement for butter on bread. The feathers and down from plucked geese can be saved up and made into comforters, pillows, and warm vests.

Ducks and geese get along well together and can be kept in the same area. In fact, since domestic ducks don’t fly well or at all, and some are too heavy to even walk fast, and since geese tend to be aggressive toward trespassers, ducks enjoy some measure of protection from predators when kept together with geese.

Ducks can make a highly effective pest patrol in the garden, as long as you take care to keep them from tender plants and low-growing fruit.

Numerous breeds of duck and goose can be found worldwide, and more are created all the time. Others, however, are becoming endangered or extinct. Only a few of the developed breeds are commonly found in the United States. Other breeds with much lower populations are kept by fanciers or conservation breeders. Your purpose in keeping waterfowl will to some extent determine which breed is right for you.

Some breeds of duck have been genetically selected for their outstanding laying habits, but unless this ability is maintained through continued selective breeding, the laying potential of a particular flock may decrease over time. For this reason, not all populations of a breed known for laying are equally up to the task. Some sources offer hybrid layers that are bred for efficient and consistent egg production, but their offspring will not retain the same characteristics. Since laying stops when nesting begins, the trade-off among laying breeds is that they generally do not have strong nesting instincts. Although some ducks lay eggs with pale green shells, most of the outstanding layers produce white-shell eggs.

Any breed can be raised for meat, but some breeds and hybrids have been developed to grow faster and larger than others while consuming less feed. The larger, meatier breeds do not lay as well as the midsize dual-purpose (egg and meat) breeds or the smaller breeds kept primarily for eggs. Breeds with white or light-colored feathers pluck cleaner, although the breeds with more colorful plumage are less visible to predators.

Ancona. Originating in England, the Ancona is a hardy dual-purpose breed that lays well and grows rapidly. It is an excellent forager, and because it is active, its meat tends to be leaner than that of less active breeds. The Ancona comes in several color varieties with a patternless patchy plumage color that is often compared to the appearance of Holstein cattle.

Appleyard. Originating in England, the Appleyard is a dual-purpose breed that lays well, grows rapidly, and forages actively, producing somewhat lean meat. Its color is similar to that of the wild Mallard, only a little lighter. Thanks to its silvery hue, this breed is sometimes called Silver Appleyard.

Aylesbury. Originating in England, the Aylesbury is among the largest duck breeds raised primarily for meat, and also among the breeds that put on the most fat. Ducklings can grow to about 5 pounds (2.25 kg) in only seven to nine weeks. This breed is not as hardy as other meat breeds and is not an active forager. Unlike most other ducks, which have yellow skin, the Aylesbury has white skin underneath its white plumage.

Buff (Orpington). Originating in England, the Buff duck is a dual-purpose breed, being a relatively good layer and rapid grower. Its light-brown plumage color is generally known as fawn brown. In England this breed is called the Orpington, with buff being but one of its color varieties.

Campbell. Originating in England, the Campbell is the most prolific layer of all duck breeds. It is an active forager that is adaptable to a wide range of climates. Of the various color varieties, khaki is the most common in North America. This small-bodied duck, if slaughtered when young and tender, makes a nice meal for two.

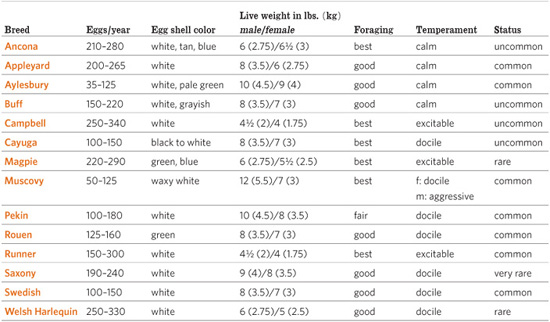

Quick Guide to Duck Breeds

Cayuga. Originating in New York, the Cayuga is a dual-purpose breed. It is an active forager and among the hardiest of domestic ducks. Eggs laid by young hens start out with a black film that disappears as the hens age, and eventually they lay white eggs. Because of the Cayuga’s greenish black plumage, ducks don’t pluck clean and instead are sometimes skinned.

Magpie. Originating in Wales, Magpies are among the better laying lightweight breeds. They are active foragers, and the lean meat of a young, tender duck is enough to serve two or three diners. The Magpie plumage is primarily white, with dark to black patches on the head and back.

Muscovy. Native to Mexico, and Central and South America, the Muscovy doesn’t look like any other domestic duck and, indeed, is only distantly related to the others. Muscovies are sometimes called quackless ducks because, in contrast to the loud quacking of other female ducks, the Muscovy female speaks in a musical whimper, although she can make a louder sound if startled or frightened. The male’s sound is a soft hiss. Aging drakes take on a distinctive musky odor, giving this breed its other nickname of musk duck. Both the males and the females wear a red mask over the bridge of their beak that features lumpy warts, called caruncles.

Muscovies are arboreal, preferring to roost in trees and nest in wide forks or hollow trunks. In confinement, they like to perch at the top of a fence, but don’t always come back down on the right side. To get a good grip while perching on high, these ducks have sharply clawed toes. If you have to carry a Muscovy, try to keep it from paddling its legs so those sharp claws don’t slice your skin. Aging males can be aggressive, usually toward other male ducks but occasionally toward their keeper. With their powerful wings and sharp claws they can be pretty dangerous.

The male Muscovy matures to be the largest of the meat ducks. Although the variety with white plumage is more suitable for meat, since it has a cleaner appearance when plucked, the original color is an iridescent greenish black with white patches on the wings. Throughout the years about a dozen additional colors have been developed. Both sexes have an enormous appetite for insects, slugs, snails, and baby rodents. With their massive bodies and large flat feet, though, they can be destructive to garden seedlings.

Muscovy meat differs in flavor and texture from that of other ducks, in part because it is much leaner. It has been compared to veal, beef, and (when smoked) ham.

Even though Muscovies are a different species from other domestic ducks, they will interbreed, and the resulting offspring are mules—sterile hybrids that cannot reproduce. A cross between a Muscovy drake and a Pekin duck produces meat birds called Moulards, which have the large breast of the Muscovy with less fat than the Pekin.

Because of concerns about feral Muscovies in the environment, the United States Fish and Wildlife Service requires captive-bred Muscovies to be physically marked by one of four prescribed methods—toe removal, pinioning, banding, tattooing—and prohibits the release of Muscovies into the wild. For information on current regulations, check with your local Fish and Wildlife office, which can be located through the national service’s website.

Pekin. Developed in China, Pekins are fast growing big ducks that tend to pile on the fat. Because they have snow-white feathers, they appear clean when plucked; their white pinfeathers don’t show as much as the pinfeathers of colored breeds. Strains of giant or jumbo Pekins, which grow bigger and meatier than is typical for the breed, have been developed for commercial meat production. If you order duck in a restaurant, or buy a duck at the meat counter, it will most likely be a Pekin. The hens tend to be noisier than other breeds, which may be an important factor if you plan to raise your ducks to maturity.

Rouen. Developed in France, the Rouen looks like an overstuffed Mallard and comes in two distinct types. The production type is a reasonably decent layer and good forager; the exhibition type grows to about 2 pounds (1 kg) more and is less active. Rouens are slow growing, taking half a year or more to reach harvest weight, and their dark feathers make them difficult to pluck clean.

Runner. Developed in Scotland from stock originating in the East Indies, these ducks are put to work gleaning snails and waste grain from rice paddies. Runners have an upright stance that allows them to move around with greater agility than other breeds; they are called runners because they prefer to run rather than waddle. They are good layers and excellent foragers, with small bodies and meat that tends to be somewhat like wild duck. Known also as Indian Runners, they come in more color varieties than any other breed.

Saxony. Developed in Germany, the Saxony is a large dual-purpose breed that lays well, actively forages, and easily adapts to a wide range of climates. The Saxony is a slow grower, yet its meat is not especially fatty. The drake’s plumage is similar to that of a Mallard; the duck is a buff color with silvery blue wings.

Swedish. Coming from Pomerania—an area once occupied by Sweden but that has since been divided between Poland and Germany—the Swedish duck is a dual-purpose breed that lays decently well and is similar in body type to a Pekin. It comes in several color varieties, the best known of which is blue with a white bib, giving rise to its common name of Blue Swedish. It is one of the hardiest breeds, an extremely active forager that does not do well in confinement, and a slow grower.

Welsh Harlequin. Developed in Wales, the Harlequin is a lightweight dual-purpose breed, excellent layer, and active forager, although it lacks a strong sense of self-preservation that makes it vulnerable to predators and inclement weather. Its body type is similar to that of a Campbell. The plumage of the hen is creamy white with dark brown spots along the back. The drake’s color pattern is somewhat similar to, though much lighter than, a Mallard.

Most domestic goose breeds have been developed for meat, although some are bred with emphasis on other attributes. The Sebastopol, for instance, has long, curly feathers that look like a misguided perm, while the diminutive Shetland was bred to thrive in a harsh environment. Nearly every breed has a tufted version, meaning the goose has a puff of feathers growing upright on top of its head. No breed lays as prolifically as a duck, and although a single goose egg makes a formidable omelet, the eggs are more often used for hatching or for creating craft items such as decorative jewelry boxes.

The main criteria when selecting a breed to grow for meat is the size relative to the number of people you typically feed and the color of the plumage. The darker breeds, especially Toulouse, are more difficult to pluck clean due to their dark pinfeathers. For meat grown as naturally and as economically as possible, ability to forage becomes important. All breeds forage to some extent, although if your geese will be garden weeders, you may want to avoid the soil compaction that typically occurs with the heavier breeds.

African. The origin of the African goose is unknown; it is most likely related to the Chinese goose. The African is a graceful breed with a knob on top of its head and a dewlap under its chin. The brown variety, with its black knob and bill, and brown stripe down the back of its neck, is more common than the white variety with orange knob and bill. Because the knob is easily frostbitten, Africans must be sheltered in cold weather. This breed is among the most talkative and also among the calmest, making it easy to confine. Africans, like Chinese, tend to have leaner meat than other breeds, and the young ganders grow fast—reaching 18 pounds (8 kg) in as many weeks.

American Buff. Developed in North America for commercial meat production but remaining quite rare, the American Buff is a pale brown goose with brown eyes. This breed is known for being docile, friendly, and affectionate. The American Tufted Buff is a separate breed (developed by crossing American Buff with Tufted Roman), but similar except for having a bunch of feathers sprouting from the top of its head. The Tufted is hardier and somewhat more prolific than the American Buff. Both breeds are active, curious, and relatively quiet.

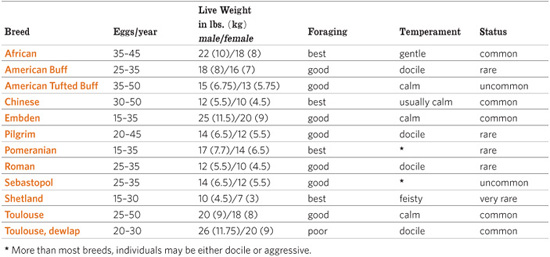

Quick Guide to Goose Breeds

Chinese. Originating in China, the Chinese goose is similar in appearance to the African but lacks the dewlap. It comes in both white and brown, with the brown variety having a larger knob than the white. Like the African, Chinese need protective winter shelter to prevent frostbitten knobs. This breed is the one most commonly used as weeder geese. Because they are both active and small, they do a good job of seeking out emerging weeds while inflicting little damage on established crops. Thanks to their light weight and strong wings, they can readily fly over an inadequate fence. In contrast to the typical goose honk, this breed (like the African) emits a higher pitched “doink” that can be piercing if the bird is upset or irritated. Chinese geese are prolific layers that produce a high rate of fertile eggs even when breeding on land rather than on water. Like African geese, the young grow relatively fast and have lean meat.

Embden. Originating in Germany, the Embden is the most common goose to raise for meat because of its fast growth, large size, and white feathers. Hatchlings are gray and can be sexed with some degree of accuracy, as the males tend to be lighter in color than the females. Their blue eyes, tall and erect stance, and a proud bearing give these geese an air of intelligence. Although they are not as prolific at laying as some other breeds, the eggs are the largest, weighing 6 ounces (170 g) on average.

Pilgrim. Originating in the United States, the Pilgrim is slightly larger than the Chinese and one of the few domestic breeds that can be autosexed—the male hatchling is yellow and grows into white plumage, while the female hatchling is olive-gray and grows into gray plumage similar to the Toulouse but with a white face. Due to their light weight, Pilgrims will often fly over a fence if attracted to something on the other side. The Pilgrim is a quiet breed and more docile than most other geese.

Pomeranian. Originating in northern Germany, the Pomeranian is a chunky breed with plumage that may be all buff, all gray, all white, or saddleback (white with a buff or gray head, back, and flanks). This breed is winter hardy and an excellent forager starting at a young age, when goslings need plenty of quality greens to thrive. More than most, the Pomeranian’s temperament is variable and can range from benign to belligerent.

How Long Do Waterfowl Live?

Few waterfowl live out their full, natural lives. Too many get taken by predators. Those raised for meat have a short life of as little as 6 weeks for ducks or up to 6 months for geese. Ducks raised for eggs or as breeders are usually kept for 3 to 5 years, until their productivity and fertility decline. But when properly fed and protected from harm, a duck may live as long as 20 years, while a goose may survive to the ripe old age of 40.

Roman. Coming from Italy, the Roman is a small, white goose that may be smooth headed or tufted—having a stylish clump of upright feathers at the top of the head. The Roman is similar in size to the Chinese, making it equally ideal as a meat bird for smaller families, although the Roman’s short neck and back make it somewhat more compact than the Chinese. This breed is known for being docile and friendly.

Sebastopol. Arising from the Black Sea area of southeastern Europe, the Sebastopol’s claim to fame is its long, flexible feathers that curl and drape, giving the goose a rumpled look. The looseness of the feathers makes this goose less able to shed rain in wet weather or stay warm in cold weather. Varieties come in white, gray, or buff plumage, which requires bathing water to maintain its good condition. Lacking proper wing feathers, the Sebastopol cannot fly well.

Shetland. Coming from Scotland, Shetland geese are exceptional foragers that, given ample access to quality greens, can basically feed themselves. Like Pilgrims, they are autosexing—the gander is mostly white, while the goose is a gray saddleback (white with a gray head, back, and flanks). The Shetland is the smallest, lightest-weight domestic breed with powerful wings that result in a dandy ability to fly. These tough little geese have a reputation for being feisty, but given time and patience, they can be gentle and friendly.

Toulouse. Originating in France, the Toulouse comes in two distinct types. The production Toulouse is the common gray barnyard goose; the Dewlap, or Giant, Toulouse gains weight more rapidly, puts on more fat, and matures to a much more massive size, especially when bred for exhibition. The dewlap consists of a fold of skin hanging beneath the bill, growing more pendulous as the goose grows older. In contrast to the more active production Toulouse, the Dewlap Toulouse is less inclined to stray far from the feed trough and puts on more fat, which when rendered lends a wonderful flavor to baked goods.

If you can’t decide whether to raise ducks or geese, why not get both? Ducks and geese are compatible and can be housed together in the same facilities, as long as sufficient space is provided. Like most birds, ducks and geese are social animals that don’t like to be alone, so you will need at least two. If you want to raise young in the future, they must be a pair. If you plan to keep your waterfowl into maturity but don’t expect to breed them, you can get by with all females. They will lay eggs, and may try to nest, even if no male is around to fertilize the eggs. Among ducks, the male is quieter than the female (except among Muscovies, which are both quiet); among geese, the male tends to be louder than the female.

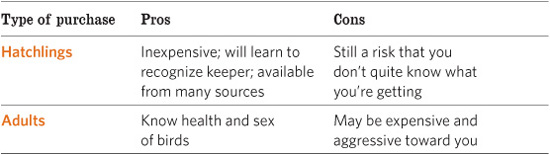

If you are looking for a breeding pair, getting grown birds has the advantage that you can see what you’re getting, but they may be expensive and will not necessarily recognize you as a friend. If you cannot find the breed you want locally, shipping mature birds is both expensive and a hassle. Ducklings and goslings are much cheaper. If you want breeders to produce future ducklings and goslings, getting a batch of straight-run hatchlings lets them grow up in familiar surroundings and learn to recognize you as their keeper. As they grow, you can pick out the best for future breeding and put the rest in the freezer. When you grow meat from hatchlings, you will know exactly what they have been fed throughout their lives.

Hatchlings are available from more sources than are adult waterfowl. One place to look is the local farm store. Either the farm store or your county Extension office can tell you if any hatcheries or waterfowl farms are in your vicinity. The larger operations might advertise in the Yellow Pages of the phone book, newspaper classified ads, or freebie newspapers. The farm store and Extension office can also tell you of any local waterfowl or poultry clubs in your area. Attending a poultry show at the county fair is another way to connect with sellers, as well as with like-minded folks who are willing to share their experiences and expertise.

Purchasing Options

If you have difficulty finding the breed you want locally, seek out a mail-order source, many of which advertise in farm and country magazines and on the Internet. If you desire one of the less common breeds, you might find a seller through the American Livestock Breeds Conservancy, the Society for the Preservation of Poultry Antiquities, or Rare Breeds Canada. Hatchlings shipped on their first day of life usually survive the trip, although you’ll be required to purchase a minimum number so they can keep each other warm. When the shipment arrives, open the box immediately and inspect the ducklings or goslings in front of the postal carrier, so you can make a claim in case any have died in transit.

When purchasing adult waterfowl, seek birds that are still young. Even though ducks and geese can live for many years, their fertility and laying ability decline with age. Ducks are at their prime age for breeding from 1 to 3 years of age, and geese from 2 to 5 years of age. Indications that a bird is still young are a pliable upper bill, a flexible breastbone, and a flexible windpipe. Another sign is blunt tail feathers, where the once-attached down has broken off. After a bird molts into adult plumage, it acquires the rounded tail feathers of an adult, and once it reaches full maturity, you’ll have a hard time determining its age and will have to take the seller’s word.

Before taking your birds home, make a final check for problems, such as crooked backs or breastbones. In geese, also check for nonsymmetrical pouches between the legs. Look for signs of good health: alertness, clear eyes, proper degree of plumpness, and normal activity level.

Like other barnyard poultry, waterfowl hatchlings are precocial, meaning that soon after they hatch they are out and about, exploring their surroundings. Their downy coats offer some protection from the elements, but if they have no mother duck or goose to shelter them from cold and rain (not to mention fending off predators), they must be housed in a brooder until they are old enough to manage on their own.

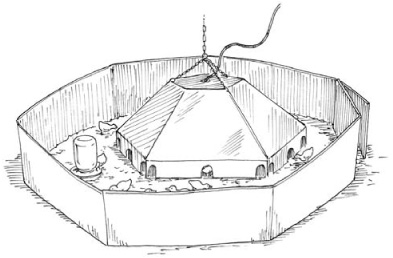

A brooder is a protected place that provides a growing bird with safety, warmth, food, and water. A home brooder can be made from a large, sturdy cardboard box. Line the box with newspapers then a layer of paper towels for the first week, to provide sure footing. A sheet of small-mesh wire fastened across the top of the box keeps out rodents, household cats, and other predators. An empty feed sack or a few sheets of newspaper covering the mesh guards against drafts.

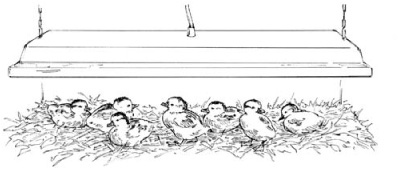

The typical source of brooder warmth is a lightbulb or infrared heat lamp screwed into a metal reflector, but a hot glass bulb can shatter if splashed with cold water by playful hatchlings. A safer alternative, and a good investment if you plan to raise young waterfowl in the future, is a sealed infrared pet heater, such as the panels made by Infratherm. Hang the heater by a chain that allows you to raise the panel as your waterfowl grow. Be prepared to provide heat until the birds feather out. The rules of thumb are as follows.

Start the brooder temperature at 90°F (32°C). Decrease it five degrees per week until you get down to 70°F (21°C). If the days are warm and nights are cool, you may need to provide heat only at night after the first couple of weeks. Once the hatchlings have feathered out, at about 6 to 8 weeks, they won’t be bothered by a temperature as low as 50°F (10°C).

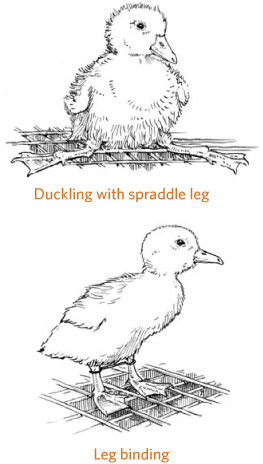

A hatchling does not have strong legs. If it is forced to walk on a slick surface in the incubator, brooder, or shipping box, its feet can slide out from under and splay in two directions. To keep the feet together, bind the legs loosely with a piece of soft yarn tied in a figure eight or a rubber band knotted at the center. Provide a rougher surface, such as paper towels or hardware cloth, to ensure firm footing. Watch closely to make sure the hobble does not get too tight, and remove it after a couple of days as the legs toughen up enough to hold the bird.

To gauge brooder temperature, you don’t need a thermometer. Just watch how your ducklings or goslings react to the source of heat. If they remain normally active, they are comfortable. If they huddle under the heater and peep loudly, they are cold. If they spread as far as possible away from the heat and pant, they are hot. (See the illustrations on page 21 for details.)

When hung from a chain, a hover brooder—shown here with draft guard—can be raised as ducklings grow in size.

A sealed infrared panel pet heater won’t shatter like a lightbulb or infrared heat lamp might if splashed with water by playful baby waterfowl.

As they grow, the hatchlings will naturally generate more body heat and rely less on artificial heat. The more rapidly you reduce the heat you provide (by raising the heater panel or, if using bulbs, reducing the wattage), the more rapidly your waterfowl will feather out and become less dependent on the electric heat you are using.

For the first day or two the hatchlings will spend a lot of time resting and require little more than about ¼ square foot (8 sq cm) per duckling and twice that per gosling. As soon as they become active they will need three times the space up to 2 weeks of age, when their space needs will double. Their needed space will double again by the third or fourth week and double again from the fifth or sixth week, or until the weather is warm enough for them to spend time outdoors. The sooner they can get outside, the easier it will be to keep their brooder space clean and dry.

Good sanitation throughout the brooding period means dealing with all the moisture and fluid droppings waterfowl generate. For the first few days while the hatchlings are on paper towels, freshen the box by adding a new layer of towels, then periodically roll them all up and start over. As the young waterfowl grow, they will generate increasingly greater quantities of wet mess that can’t be handled with paper. At that point, you must move them to an area covered with at least 3 inches (7.5 cm) of absorbent bedding, such as shredded paper or wood shavings, and replace any bedding that becomes soaked.

Baby ducks and geese love to play in water. This attraction leads to two serious problems: They can quickly make a mess of even the best-kept brooder, and they can just as quickly make an unsanitary mess of their drinking water. An open source of drinking water, such as a pan or bowl, is therefore unsuitable for brooding waterfowl. For the first two weeks of their life, a satisfactory container is a circular chick waterer that screws onto a water-filled jar.

Raised naturally, ducklings and goslings will happily swim with their parents. The older birds will control how long the babies stay in the water and when they must come out. Left on their own, however, ducklings and goslings may play in the water long after they should come out, becoming soaked, chilled, and possibly ill (or worse). Artificially brooded waterfowl should not have unsupervised access to water deep enough to swim in.

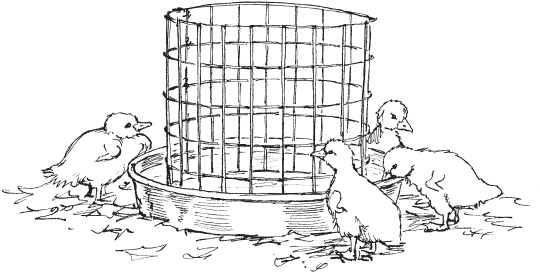

This homemade waterer is made with a wire cylinder in an open pan.

As the birds grow and require enough water in which to submerge their heads, a deeper trough becomes more suitable. The trough must not be easy for the birds to tip by stepping onto the rim, should be placed over a drain that channels overflow and spills away from the brooding area, and should be covered with a wire grate to prevent swimming. If your ducklings and goslings can swim or walk in the water, they will leave droppings in the drinking water that can lead to disease. The grate or wire mesh must be big enough to allow them to get their heads through for a drink.

If, in a pinch, you need to use an open container, you can float a piece of clean untreated lumber on the surface. Cut the wood to fit the container’s shape but make it slightly smaller, so your birds can drink from around the edges. Or place a short cylinder of fine-mesh wire in the center of the container, leaving space between the cylinder and the rim to allow a good drink.

Waterfowl hatchlings should have free-choice access to feed at all times. Feed them just enough twice a day to last until the next feeding. Since their appetites will grow at an alarming rate, you will need to constantly adjust the amount supplied at each feeding. Allowing waterfowl to go hungry will result in a frantic frenzy when they finally get something to eat, turning your cute downy ducklings and goslings into bug-eyed mini-monsters encrusted with caked-on feed.

Clean out the feeders frequently, taking care not to leave old, stale feed in the corners. Initially you can use feeders with little round holes designed for baby chicks. Watch carefully as your ducklings and goslings grow. When their heads get close to being too big to fit through the holes, switch to troughs with wire guards that prevent the birds from walking in the feed.

Ducklings and goslings need water to wash down dry feed. They fill their mouths with feed, waddle to the water for a drink to wash it down, then waddle back for another mouthful. Before long, a trail of dribbled feed marks the path between the feeder and the drinker. If the drinker is close to the feeder, the feed will soon be a wet mess and the water will turn to sludge.

To avoid these problems, you can moisten the feed with water or skim milk, but you will have to offer less feed at a time and therefore provide feed more often. Left too long, moistened mash clumps together, discouraging your waterfowl from eating. Furthermore, in the warmth of the brooder, it may turn sour or moldy, causing illness if it is eaten.

Finding a commercial starter ration formulated for baby waterfowl can be a challenge. A good substitute for the first few days is mashed hard-cooked egg. Chick starter crumble can then be fed, provided it is not medicated and you fortify it with livestock grade brewer’s yeast (3 pounds [1.5 kg] brewer’s yeast per 25 pound [11.5 kg] bag starter) to prevent niacin deficiency. Grower ration is generally high in protein to promote fast growth in meat birds. If that is not your goal, reduce the protein level by supplementing the ration with high-fiber feed, such as chopped lettuce or succulent grass. The natural diet of goslings consists almost entirely of freshly sprouting grass. If you have access to a grassy area that has not been sprayed with chemicals, on sunny days you can move your ducklings and goslings outside to graze in a small portable enclosure that provides protection from predators and cold wind. Alternatively, chop lettuce and other tender greens, or sprout alfalfa or similar seed, for your babies. Small amounts, floated in the drinking water, will quickly disappear.

When warm weather allows ducklings and goslings to spend most of their time grazing, you can cut their commercial feed back to the amount they can clean up in 15 minutes, twice a day. When they reach the age of 1 month, you can feed only once a day, preferably at night, so they’ll be hungry in the morning and take greater advantage of the natural forage.

Excess protein in the diet and insufficient exercise may result in twisted wing.

Letting young waterfowl graze helps prevent twisted wing, a condition in which the flight feathers of one or both wings angle away from the body like an airplane’s wings. This problem, also known as slipped wing, occurs because the flight feathers grow faster than the underlying wing structure. The heavy feathers pull the wing down, causing it to twist outward. When the bird matures, one or both of its wings remain awkwardly bent outward instead of gracefully folding against its body. Meat birds don’t live long enough for this clumsy appearance to present a problem, but it is unsightly in mature waterfowl. You can easily prevent twisted wing by avoiding excess protein.

Sexing Ducklings and Goslings

Although baby ducks all sound the same, as they grow, the drakes lose their voice. Soon the drakes of Mallard-derived breeds develop conspicuous drake feathers that curl up and forward at the end of the tail. Among Muscovies, the drakes are about twice the size of the hens.

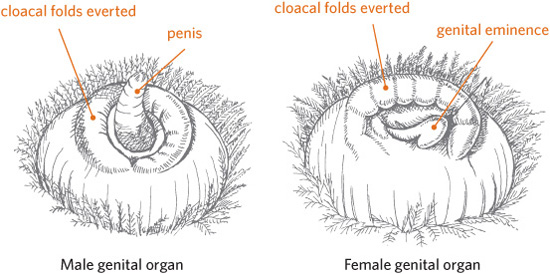

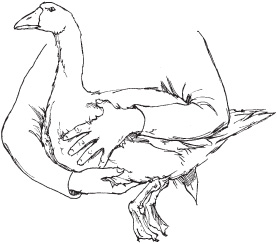

If you must separate the hens from the drakes while they are young, the only way to do it is by vent sexing, as described on page 102. Among geese that cannot be sexed by a difference in color between the males and the females (autosexing), vent sexing is the only accurate way to distinguish sex, even once they’re mature. Vent sexing young waterfowl takes a considerable amount of practice to be accurate without injuring a delicate bird. If you don’t have experience in vent sexing, find a professional to help you learn.

Probiotics

Probiotics are beneficial bacteria that are naturally present in the digestive tract of animals. These beneficial bacteria increase in numbers as the animal matures and, when the body is in proper balance, fight off disease-causing bacteria. By adding a probiotic formula designed for poultry to the drinking water of ducklings and goslings during their first week of life, you can give them a good start.

Ducklings and goslings are incredibly hardy and, when properly cared for, are not particularly susceptible to disease. Their health is easily maintained by providing a clean, dry environment, adequate heat and ventilation, proper nutrition, fresh feed, and clean water. Then stand back and watch them grow.

Ducklings must be brooded until they are about 4 weeks old and goslings until about 6 weeks. If the weather is mild by then, they can be moved outdoors, but they still need shelter from wind, rain, and hot sun. In stormy weather, gather them up and bring them inside until they are fully feathered, which will be around 12 weeks for Mallard-derived ducklings and 16 weeks for Muscovies and goslings.

When you first turn them outdoors, keep an eye on them. Ducklings and goslings have an uncanny ability to find escape routes, get stuck in odd nooks, or get separated from their feed and water. If their yard is large or they are being turned out with mature ducks and geese, confine them to a small part of the yard for the first few days, enlarging their space only after they have had time to get their bearings.

Some breeds of waterfowl have been developed especially for efficient meat production, but any breed is good to eat. If you purchase a duck or goose at the grocery store or butcher shop, the duck would most likely be a Pekin and the goose an Embden. These white-feathered breeds appear cleaner when plucked, because their white pinfeathers don’t show as much as the pinfeathers of darker waterfowl.

A typical feed conversion rate for waterfowl raised for meat is 3 pounds (1.5 kg), meaning each bird gains 1 pound (0.5 kg) of weight for every 3 pounds (1.5 kg) of feed it eats up to about 8 weeks old. The older a bird gets, the higher the feed conversion rate, creating a trade-off between economical meat and more of it. To improve the conversion rate, commercially raised waterfowl are encouraged to eat continuously by being kept under lights 24 hours, having their feed troughs topped off every few hours, and being confined to a limited area to discourage them from burning off calories. In addition to growing fast, these ducks put on a lot of fat.

Pasture-raised waterfowl take longer to grow to similar weight, and more of that weight is meat instead of fat. During that time, the feed conversion rate for ducks will go up. On the other hand, geese that have plenty of forage for grazing will have a reduced need for commercial rations. Once goslings have been growing well on starter for about a month, they will continue to grow on good grazing for about four months (although they’ll grow faster if given supplemental grain), and then finished on grain or finisher ration for the last month before slaughter.

Can you save money by raising your own ducks and geese? That depends on the price of feed, how much the cost can be reduced by providing good forage, and the price you’re paying for meat now. Using averages (and for simplicity’s sake, ignoring the cost of housing, water, electricity, and so forth), do the math: By the time a Pekin reaches the live weight of 7 pounds (3 kg) it will have eaten about 20 pounds (9 kg) of feed. At 75 percent of live weight, a 7-pound (3 kg) duckling dresses out to approximately 5¼ pounds (2.25 kg). Your break-even cost can be calculated by comparing the purchase price of a dressed Pekin of similar weight with the cost of starter/grower ration. At current prices, a dressed duckling sells for anywhere from $15 to $35. The current rate for one brand of all-natural starter/grower ration is about 25 cents per pound, or about $5 for 20 pounds, which is one-third the value of a $15 duck. Even after adding $4 for each duckling, that’s a pretty good deal. But if you choose to pay 50 to 100 percent more to purchase certified organic feed, you come close to breaking even. Raising geese is a much better deal, provided they have access to high-quality forage, because they can live almost entirely by grazing for the better part of the growing period.

Weight gain is only one important factor in determining when a duck or goose is ready for butchering. The other is the stage of the molt. All those feathers that allow ducks and geese to swim comfortably in cold water take a long time to remove, and plucking is considerably more difficult if some of those feathers are only partially grown. Plucking is less time-consuming, and the result is more appealing, if a duck or goose is in full feather.

Soon after a duck or goose acquires its first full set of feathers, it begins molting into adult plumage and won’t be back in full feather for another two months or so. You’ll know the optimal time to pluck a duckling or gosling has passed when the feathers around its neck start falling out. From then on, the bird won’t grow as rapidly as it has been and for ducks the feed conversion rate goes up. After this point, feeding ducks for meat purposes becomes more costly, the meat becomes tougher, and the meat of Muscovy males takes on an unpleasant musky flavor. Geese, on the other hand, are traditionally roasted during the holidays, so are generally butchered in the fall after their second molt, when they are about 6 months old.

Most ducks reach full feather when they are between 7 and 10 weeks old. Muscovies reach full feather at about 16 to 20 weeks. A duck or goose is in full feather and ready for slaughter when all of these signs are present:

• Its flight feathers have grown to their full length and reach the tail

• Its plumage is bright and hard looking, and feels smooth when stroked

• You see no pinfeathers when you ruffle the feathers against the grain

• It has no downy patches along the breastbone or around the vent

A duck or goose loses 25 to 30 percent of its live weight after the feathers, feet, head, and entrails have been removed. Heavier breeds lose a smaller percentage than lighter breeds. The breast makes up about 20 percent of the total meat weight; skin and fat make up about 30 percent.

When all of these signs are right, a duck or goose is ready to be butchered. If you are doing your own butchering for the first time, have an experienced person guide you, or refer to a comprehensive book such as Storey’s Guide to Raising Ducks by Dave Holderread (butchering geese is similar to ducks, the main difference being they are much larger). If you don’t wish to do your own butchering, you might find a custom slaughterer willing to handle ducks and geese. Alternatively, a fellow backyard waterfowl keeper or a hunter might be willing to kill and pluck your ducks or geese for a small fee. If not having to kill your own waterfowl is important to you, determine before you start whether or not someone in your area will do it for you.

Freshly butchered duck or goose must be aged in the refrigerator for 12 to 24 hours before being cooked or frozen; otherwise, it will be tough. If you will not be serving the duck or goose within the next three days, freeze it after the aging period until you’re ready to cook it. To avoid freezer burn, use freezer storage bags. Most ducks will fit in the 1-gallon (3.5 L) size. A Muscovy female should fit in the 2-gallon size. Geese and Muscovy males should fit in the 5-gallon (19 L) size. Remove as much air from the bag as you can by pressing it out with your hands or by using a homesteaders’ vacuum device designed for that purpose. Properly sealed and stored at a temperature of 0ºF (–18ºC) or below, duck and goose meat can be kept frozen for six months with no loss of quality. To thaw a frozen goose or duck before roasting, keep it in the refrigerator for two hours per pound (0.5 kg).

A whole duck or goose takes up a lot of freezer space. Unless you intend to stuff and roast the bird, you can save space by halving or quartering it, or filleting the breasts and cutting up the rest. Muscovy breast makes an exceptionally fine cut that is the most like red meat of any waterfowl. After removing the fillets, you might package the hind-quarters for roasting or barbecuing and boil the rest for soup. A great use for excess Muscovy and goose meat is making sausage, using the same recipes that are intended for pork. Small amounts can easily be made into sausage patties, whereas larger amounts can be stuffed into links.

Contrary to common belief, a properly prepared, homegrown duck or goose should not be greasy. Although ducks and geese have a lot of fat, the meat itself is pretty lean. All the fat is either just under the skin or near one of the two openings, where it can easily be pulled away by hand before the bird is roasted.

Proper roasting begins by putting the meat on a rack to keep it out of the pan drippings while the bird cooks. Remove any fat from the cavity and neck openings, and stuff the bird or rub salt inside. Rub the skin with a fresh lemon, then sprinkle it with salt. Pierce the skin all over with a meat fork, knife tip, or skewer, taking care not to pierce into the meat. Your goal in piercing is to give the fat a way out through the skin as it melts during roasting. This melted fat will baste the bird as it drips off, so no other basting is required. Do not cover the duck or goose with foil during roasting as you would a turkey.

Slow roasting keeps the meat moist. Roast a whole duck at 250ºF (120ºC) for 3 hours with the breast side down, then for another 45 minutes with the breast up. Roast a goose at 325ºF (160ºC) for 1½ hours with the breast side down, plus 1½ hours breast up, then increase the temperature to 400ºF (205ºC) for another 15 minutes to crisp the skin.

Since not all birds are the same size and not all ovens work the same way, keep an eye on things the first time around, to avoid overcooking your meat, which makes it tough and stringy. Once you settle on the correct time range for birds of the size you raise, you can roast by the clock in the future.

When the meat is done, it should be just cooked through and still juicy. You can tell it’s done when the leg joints move freely, a knife stabbed into a joint releases juices that flow pink but not bloody, and the meat itself is just barely pinkish. To keep the meat nice and moist, before you carve the bird, let it stand at room temperature for 10 to 15 minutes to lock in the juices. During this time, residual heat will cook away any remaining pink. Duck or goose does not have light and dark meat like a chicken or turkey; rather, it is all succulent dark meat.

Cooking Methods

The most suitable method of cooking a duck or goose depends on its tenderness, which in turn depends on its age. Fast dry-heat methods, such as roasting, broiling, frying, and barbecuing, are suitable for young, tender birds; slow moist-heat cooking methods, such as pressure cooking or making a fricassee, soup, or stew, are required for older, tougher birds.

The better layers among ducks, kept under optimal conditions, may begin producing eggs as early as 18 weeks of age and continue laying nearly year-round. Breeds, and strains within breeds, that have been developed for meat or ornamental purposes do not lay nearly as well as those that have been selectively bred for their laying ability. The best layers stop production only briefly during the fall molt.

Most geese hit their stride in their second year of life and peak at 5, although they may lay for up to 10 years. Muscovies may lay for six or more years. Mallard-derived ducks normally lay well for three years, and some strains continue to lay efficiently for up to five years. If your purpose in keeping a bevy is egg production, replace older ducks before they lose efficiency.

Most domestic ducks and geese start laying early in the spring of their first year. How well they lay and the length of their laying season depends on the following factors:

• Breed

• Strain (subgroup within the breed)

• Age

• Diet

• Overall health

• Weather

• Daylight hours

Waterfowl tend to lay in the early morning hours. Ducks generally lay one egg every day, geese one every other day. The less productive breeds will lay a consecutive batch of eggs, called a clutch, and then take up to two weeks off before starting another clutch. If you leave a clutch in the nest, a duck or goose may start setting and stop laying for the season.

Egg size depends in part on the breed and the strain, but mostly on the size of the bird. Larger birds lay larger eggs. Smaller, yolkless eggs commonly signal the beginning and end of a bird’s laying season, but they may also be laid during hot weather, especially if drinking water is in short supply.

Geese lay white eggs. Ducks may lay white, greenish, or bluish eggs.

As the laying season approaches, ducks and geese require more nutrition. About three weeks before you expect them to start laying, gradually switch from maintenance ration to a layer ration that contains 16 to 20 percent protein. In warmer weather, fowl need more protein to keep eggs from getting smaller. If your farm store doesn’t carry layer ration for ducks, layer ration formulated for chickens works well.

For sound, thick eggshells, provide calcium continuously throughout the laying season. Ducks and geese that have access to forage usually get plenty of calcium from the shells of bugs and snails they eat. Still, it’s a good idea to provide them with a free-choice hopperful of crushed oyster shells, ground aragonite, or chipped limestone (not dolomitic limestone, which can be detrimental to egg production).

Providing nests for your ducks and geese to lay their eggs in helps keep the eggs clean and protects them from being cooked by sun, washed by rain, or frozen in cold weather. Eggs laid in nests are easier for you to find than eggs hidden in the grass, but the latter are more difficult for predators to find. As a rule of thumb, furnish one nest per three to five females.

Lighting Layers

If your waterfowl live naturally and forage for much of their food, you likely won’t get the number of eggs quoted by sellers and listed in the Guide to Duck Breeds on page 73. To lay really well, mature hens must be fed carefully formulated rations and be housed under at least 14 hours of light year-round.

To keep your birds laying during the shorter days of late fall, winter, and early spring, you can use electric lights to augment natural daylight. Inside the shelter, use one 40-watt bulb (10-watt fluorescent) for every 150 square feet (46 sq m); outside the shelter, use one 100-watt bulb (25-watt fluorescent) for every 400 square feet (122 sq m). If your duck yard doesn’t have electricity, you can provide lighting with 12-volt bulbs designed for recreational vehicles, powered by a battery connected to a solar recharger.

Use an inexpensive reflector from the hardware store to direct the light appropriately, and hang the bulbs about 6 feet (2 m) off the ground to reduce shadows. Adjust your lighting times as needed to maintain 14 hours or more of light per day. Even a minor reduction in light hours can throw off the production of laying ducks. To avoid risks associated with too-early laying, do not begin your lighting program until your ducks reach 20 weeks of age.

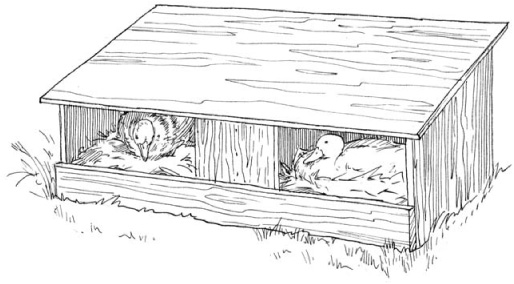

The nest can be in the shape of a box, an A-frame, or a barrel on its side and braced to prevent rolling. A doghouse makes a good goose nest; for ducks, a larger doghouse with doors at opposite ends might be partitioned in half to create two nests. A good nest size is 12 inches square (30 sq cm) for a duck, 18 inches (46 sq cm) for a Muscovy, and 24 inches (61 sq cm) for a goose; the center of the top should also be 12, 18, or 24 inches (30, 46, or 61 cm) high, respectively. The precise size is not critical, provided the nest meets the following standards:

• Tall enough for a layer to enter and sit comfortably

• Wide enough for her to turn around, since waterfowl don’t like to back out

• Small enough to offer a feeling of protective seclusion

• Separated physically or visually from the next nearest nest

• Situated in an area that is well protected from predators

• Open at only one end, so the layer can keep an eye on who might be coming

• Large enough to accommodate an abundance of soft nesting material. A thick layer of nesting material, such as shavings, dry leaves, or straw, will keep the eggs clean, reduce breakage, and prevent eggs from rolling out of the nest.

As laying season approaches, ducks and geese will start investigating available nesting sites. If they see an egg already in a nest, they will consider it a good safe place to lay and will be inclined to deposit their own eggs there. To encourage use of the nests, rather than hiding eggs in the bushes or clumps of grass, place an artificial egg in each nest. Hobby shop eggs and toy eggs available around Easter work well and, for ducks, so do golf balls. Sometimes fake eggs aren’t enough to entice a duck or goose to lay in the place of your choosing. If you keep track of the laying habits of your bevy or gaggle, you’ll know when you are not getting your proper quota and must initiate an egg hunt.

Ducks and geese encounter few problems associated with laying eggs. Still, for the health and safety of your layers, it’s important to be vigilant.

Predators. A duck or goose on the nest is not as mobile as a bird that moves freely on the ground or in water. Freedom from predators in the laying yard is therefore essential. Predators may be attracted not only to the layer but also to her eggs in the nest. The predator may peck holes in the eggs and eat them right there (as crows do) or may consider them a takeout meal (as a skunk would).

Egg binding. When an egg becomes stuck and cannot be laid, the hen is egg bound. It may happen when a duck or goose tries to lay an egg that is too big. The bird might, for example, be laying its first egg and not be quite ready, as might happen when young hens are raised under artificial light. Ducks or geese that tend to lay double-yolked eggs may also become bound. Double-yolkers occur when one yolk catches up with another, and both become encased in the same shell. Thin-shelled eggs resulting from a dietary inadequacy, such as low calcium intake, may cause egg binding, as may obesity.

Suspect egg binding if a duck or goose is listless, stands awkwardly with ruffled feathers, and has a distended abdomen. If you press gently against the abdomen of an egg-bound bird, you will be able to feel the egg’s hard shell.

Sometimes you can lubricate your finger with a water-based lubricant or petroleum jelly, then work your finger around the stuck egg to help it pass. Standing the bird in a tub of warm (not hot) water may relax her muscles enough to allow the egg to pass. Breaking the egg is a drastic option that carries the risk of injuring the duck or goose with sharp shards of shell.

Prolapse of the oviduct. Also known as eversion or blowout, prolapse is protrusion of the oviduct through the vent. It occurs when a duck or goose strains to pass an egg, damaging the tissue so it does not recede back inside after the egg is laid. It is caused by the same factors that cause egg binding or by weakened muscles due to prolonged egg production or excessive mating. Treatment may be successful if only a small portion of oviduct is everted and the treatment is begun right away. Gently wash the protruding part; coat it with a relaxant, such as a hemorrhoidal ointment; and push it back into place. Move the affected hen to a warm, dry, secluded pen and reduce the protein in her diet to discourage laying while she heals.

A nesting site should offer adequate space, privacy, and protection.

Just before an egg is laid, it is coated with a moist film called the bloom. If you ever find an egg just after it’s been laid, it will still be wet with bloom. The bloom dries quickly to form a natural protective coating.

Eggs left in the nest for a long time tend to get dirty through the layers’ comings and goings. But washing eggs removes the bloom and creates a risk that contamination will penetrate the porous shell. Lightly soiled eggs can be brushed clean. A mildly soiled egg can be washed in water that is warmer than the egg is, but should be eaten soon because it will not keep as well as an unwashed egg. Extremely soiled eggs should be discarded.

Duck Eggs versus Chicken Eggs

Duck eggs are not much different in flavor from chicken eggs and are more popular in many countries. When fried or boiled, duck eggs have a firmer texture that might be described as slightly chewy. Duck eggs have proportionally larger yolks compared with chicken eggs and therefore lend extra richness when added to batter for baked goods. Some people have a sensitivity to undercooked chicken eggs that can cause cramping but have no such reaction to duck eggs; the opposite is also true.

To avoid wasting a lot of eggs through soiling, keep conditions tidy in your waterfowl yard. Gather eggs each morning and discard any with cracked shells or holes pecked in them.

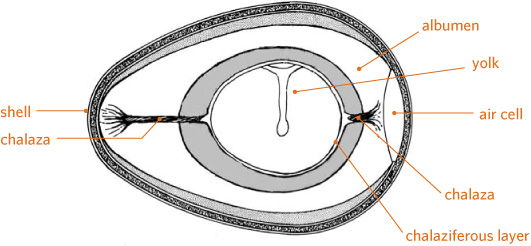

Egg anatomy. If you break open an egg and examine its contents, you will find two stringy white spots on the sides of the yolk, one of which is usually more prominent than the other. These spots are called chalazae. As the egg was being formed, a layer of dense egg white (called the chalaziferous layer) was deposited around the yolk. At the two ends of the egg, the ends of the chalaziferous layer twisted together to form a cord that anchored the yolk to the shell. When you break open an egg, the chalazae break away from the shell and recoil against the yolk. Sometimes you may also see a red or brown spot, called a blood spot, on the yolk. A blood spot is caused by minor hemorrhaging in the oviduct. Although it is harmless, it is not appetizing. The tendency to lay eggs with blood spots is inherited. If you can identify the duck laying such eggs, do not hatch her eggs, as her offspring are likely to lay blood-spotted eggs.

Storing eggs. Refrigerated duck eggs can be kept as long as two months but are best used within two weeks, while they’re still at their peak of freshness. Excess eggs to be used for baking can be stored in the freezer during the laying season for use during the off-season. Since whole eggs burst their shells when frozen, break the eggs into a bowl, add a teaspoon of honey or a half teaspoon of salt per cup (depending on your preference and the recipe you will use the eggs in), and scramble the eggs slightly, taking care not to whip in air bubbles. Pour the mixture into ice cube trays and freeze it solid, then remove the cubes from the trays and store them in well-sealed plastic bags. The frozen cubes take about 30 minutes to thaw and can be stored for up to one year at a temperature no higher than 0°F (–18°C).

Ducks are at their prime age for breeding from 1 to 3 years of age; geese take a little longer to mature and are at their prime from 2 to 5 years of age. Yearling geese lay eggs, but those eggs won’t hatch as consistently during the first year as in subsequent years. A drake is fertile by the age of 6 months and peaks after the third season. A gander reaches his prime of fertility at 3 years of age and peaks at 6 years. A duck or goose will lay eggs regardless of whether or not a male is present, but the eggs will not be fertile and therefore will not hatch.

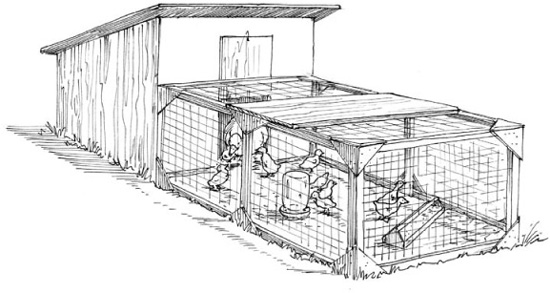

As picturesque as it may be to have ducks and geese wandering around your estate, giving them their own confined area is a wise move. Otherwise, they will congregate on your doorstep, rat-a-tat for attention on your door, and leave their slippery calling cards on your porch. Geese will try to chase away your visitors and otherwise amuse themselves by generally destroying anything that catches their attention.

The larger the area in which waterfowl can roam, the less trouble they are likely to get into and the cleaner they will remain. An area that is too small for its population will soon become muddy, mucky, smelly, and fly-ridden. The more area available for grass to grow, the better chance the grass has to survive against flat-footed waddling and the more widely duck and goose droppings will be spread, which will allow them to dissipate naturally instead of building up to create a problem.

So, although the minimum yard space requirement is about 10 square feet (3 sq m) per duck and twice that for geese, rather than considering minimums, provide as much roaming area as you can. Better yet, divide up the available yard space into paddocks so each patch of pasture can rest and rejuvenate while the birds are foraging elsewhere.

An ideal waterfowl yard has a slight slope and sandy soil for good drainage. The less ideal the area, the more space you should provide per bird. The yard should have both sunny and shady areas, letting the birds choose for themselves whether to rest in the warmth of the sun or away from its harsh rays. The yard should include a windbreak, which might consist of a dense hedge, the side of a building, or a portion of solid fence.

Fencing is essential to keep waterfowl safe from predators and prevent them from roaming too far afield. The fence must be sound and well maintained, as waterfowl are much more adept at finding ways to get out than they are at finding their way back in. How closely spaced the fencing material needs to be depends on whether or not you wish to protect vegetation on the other side. Geese especially, but ducks, too, will graze through the fence as far as their long necks can reach.

A 3- or 4-foot (1–1.25 m) fence will confine nonflying breeds. A 5- to 6-foot (1.5–1.75 m) fence would be more appropriate for Muscovies and the lighter goose breeds. If you can keep geese grounded until they reach maturity, they will have a hard time getting enough elevation to clear a fence. If you’ll be confining hatchlings, secure a 12-inch (30 cm) strip of tight-mesh wire along the bottom of the fence. Ducklings and goslings look a lot bigger in their downy coats than they really are, and they can slip through incredibly small spaces. The trouble is, after grazing on the wrong side of the fence, slipping back through with a full belly may not be quite as easy.

Minimum Living Space per Bird

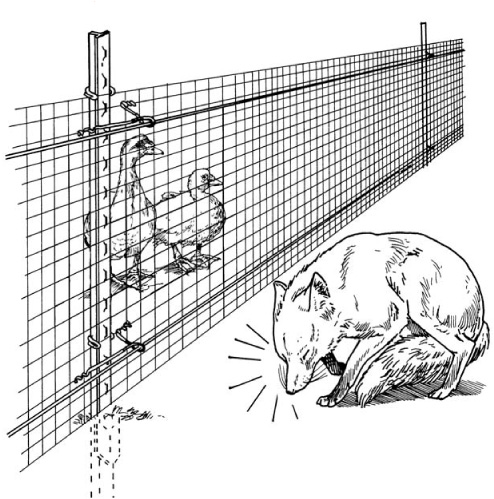

Perhaps the best fencing for waterfowl is narrow-mesh field fencing, stretched tight between posts spaced 8 feet apart (2.5 m), and augmented with electrified wire. If the electric wire is no more than 2 inches (5 cm) above the fence, any predator that attempts to climb over the field fence will get a shock when it reaches for the electric wire, causing it to drop off the fence.

As much as you like your ducks and geese, countless predators like them even more. Foxes, weasels, raccoons, and skunks have notorious appetites for waterfowl, their eggs, and their young. Dogs will chase and kill adult waterfowl for sport, and cats prey on downy hatchlings. A sturdy fence goes a long way toward keeping out most predators.

If you have a bunker mentality and the yard isn’t prohibitively large, a concrete footer all along the fence line offers a permanent, though expensive, way to discourage burrowing animals. A less expensive option is to bury the bottom of the fence below ground. A distance of 4 inches (10 cm) underground is usually sufficient, unless you live in an outlying area where a predator might dig for hours undisturbed, in which case going down 18 inches (46 cm) might be more appropriate. Depending on your soil type, you might find it easier to cut and lift a 12-inch- (30 cm) wide strip of sod along the outside of the fence line, and clip or lash a 12-inch-wide length of wire mesh to the bottom of the fence, extending out horizontally along the ground away from the yard. Replace the sod on top, and the mesh will get matted into the grass roots to create a barrier that discourages digging. To prevent soil moisture from rusting the buried portion of a fence, use vinyl-coated mesh or brush plain metal mesh with tar or asphalt emulsion.

Keeping out flying predators is nearly impossible, unless your yard is small enough, or you are ambitious enough, to cover the entire yard with netting. A less expensive alternative, that may not be visually acceptable to any nearby neighbors, is to crisscross the yard with single strands of wire placed high enough for you to walk underneath, and from the wires hang strips of old sheets, obsolete CDs or DVDs, or anything similar that flutters in a breeze and thereby discourages flying predators from landing. Still, you might find that crows or blue-jays peck holes in your eggs and owls or hawks swoop down and make off with hatchlings. Aerial predation can be further minimized by providing a roofed shelter.

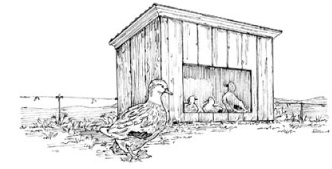

Waterfowl aren’t keen on staying indoors, but for their own protection, it’s wise to provide them with a shelter and train them from a young age to go in each night. Once they get into the routine they are likely to go in by themselves and, if you are running late, call for you to shut the door. Since most predators roam during the night, a well-built shelter will keep your birds safe during the most critical hours. It will also provide a refuge from icy wind, scorching sun, and pelting rain.

The shelter need not be spacious, since the birds will be spending only their nights in it. About 3 square feet (1 sq m) of floor space per light breed duck, 5 square feet (1 sq m) for heavy ducks, and twice those amounts for light and heavy breed geese should be plenty. For only a pair or a trio, a large doghouse-style shelter with a low roof is inexpensive and easy to clean. For a larger bevy or gaggle that requires lots of floor space, make the roof high enough for you to easily enter for cleaning.

The best way to fence out predators is to stretch narrow-mesh field fencing between posts spaced 8 ft. (2.5 m) apart and add electrified offset wires along the bottom and top.

The best floor for the shelter is packed dirt. If your area has a serious predator problem, the expense of putting the shelter on a concrete foundation, if not an entire concrete floor, may be warranted. Small windows with hardware cloth screens will let in air and allow the birds to see out, but take care to avoid drafty conditions. A cold wind blowing through feathers would remove body heat trapped by the protective undercoat of down.

Shavings on the floor help control droppings and simplify shelter clean-out. Fresh shavings also keep eggs clean if they are laid inside the shelter. Do not provide water for your ducks and geese while they are inside. The combination of the boredom of confinement and the attraction of water to play in will result in a soggy, smelly mess. Since they have no water, they also should be given nothing to eat, but don’t worry—they will get by just fine overnight and eagerly look forward to breakfast.

Because waterfowl don’t sleep at night but take catnaps, much as they do throughout the day, they will tend to be restless while confined. Lights, including moonbeams, shining through a window of the shelter and creating shadows on the walls can stir them up and cause a lot of quacking or honking. Where lights shining in from outside create shadow problems inside the shelter, hang some low-watt lightbulbs in the shelter, making sure to arrange them to avoid the birds themselves casting shadows as they move about. Protect the wiring in conduit, and hang the bulbs high enough that geese can’t dismantle your electrical efforts and get electrocuted in the bargain.

Waterfowl don’t like being indoors and should not be confined any longer than is necessary. Even in the severest climate, as long as they can find a place away from the cold wind, they prefer to be outdoors. You may think you are doing them a big favor by breaking open a bale of straw to rest on and protect their feet from cold, but don’t be surprised if they hunker down in the snow right next to the straw. Their double coat of feathers and down keeps them comfortable in weather that might send you scurrying for home and hearth. To keep their feet warm, waterfowl stand on one foot with the other tucked up, then switch and stand on the other foot while warming the first.

Because they don’t like to be indoors, you’ll need to train your bevy or gaggle from the start to go inside at night. Have a plan for getting them from their favorite resting place to the shelter door, perhaps by enlisting help or arranging doors and gates to funnel them in the desired direction. If the first time out they lead you around the barn and through the garden, be prepared to take that same circuitous route every evening from then on.

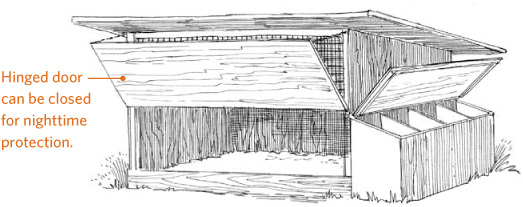

A small shelter provides nighttime protection.

Even if your birds are well trained and go in without a hitch night after night, the time will come when they will balk. If you once let them get away with not going in, they will try it night after night, trying your patience as well. But, as obstinate as they can be about not wanting to go in at night, should you come home late one evening to discover no ducks or geese in the yard, don’t panic. Chances are good they’ve gone in on their own and are impatiently waiting for you to come and shut the door.

If you don’t have an empty building to convert into a duck house, you can build a simple portable structure such as this one. The attached nests, accessible from the outside, make egg gathering easier.

Ducks and geese love to splash and play in water, and for the larger breeds water is essential for mating and egg fertility. A pond is also helpful for cleaning and conditioning plumage, and Sebastopol geese need one to maintain their good looks. Of all the various breeds, Muscovies are the only ones that seem not to mind if no pond is available for bathing and mating. For all the rest, and even for Muscovies, furnishing at least a small pond is a good idea for several reasons:

• It helps them keep themselves clean

• It improves egg fertility

• It lets them more comfortably endure hot and cold weather

• It helps them evade predators

• It lets them use up excess energy in play

• It gives you the pleasure of watching them float and frolic

Providing water is especially important if you intend to raise the large, deep-breasted breeds, which have a hard time mating without pond water to make them buoyant. And in evading predators, a goose will swim tantalizingly just offshore when tracked by a fox, and a duck will duck underwater when buzzed by a hawk.

The best reason to provide a pond is that waterfowl love water. Sure it’s hard to tell whether a duck is happy or a goose is joyful, but who can doubt it after watching a duck or goose scoot across the water, disappear beneath the surface, pop up somewhere else, flap its wings, and start again? And even if we can’t say for sure the bird is happy, it certainly makes us happy to watch. The pond needn’t be expensive or elaborate. You can build a simple pond using a guide such as Earth Ponds by Tim Matson.

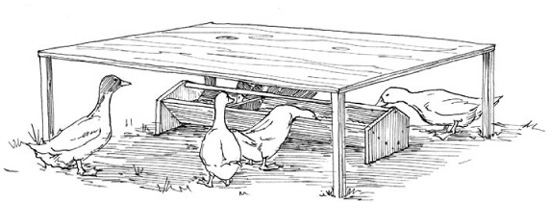

Waterfowl are happier and healthier when they have access to a pond.

Any waterfowl pond requires certain basic features to be safe for ducks and geese. It must have easy access in and out. The smallest swimmers may have serious problems if they can’t get over the rim to get out. The pond must be easy to clean or large enough to cleanse itself of waterfowl droppings. For these two reasons, a children’s wading pool is not entirely suitable, unless you can install a drain for ready cleaning and a hinged ramp that lets smaller birds climb in and out with ease, no matter what the water level.

The water should be free of any chemicals that can harm waterfowl. If your hatchlings get through the fence and make a beeline for your neighbor’s chlorine-laden swimming pool, it could well end up being their last swim.

Fish and waterfowl may be compatible in a large pond or small lake. However, in a small backyard pond, fish won’t appreciate waterfowl deposits or stirred-up mud, won’t take kindly to frequent draining and cleaning, and certainly won’t like being swallowed by some duck or goose. In a larger body of water, bass and other fish may eat hatchlings, and snapping turtles can grab a grown duck by a foot and pull it underwater.

If your first waterfowl are babies, confine them indoors until they are old enough to go out on their own. Baby waterfowl with no parents don’t have the sense to come in out of the pond or out of the rain and will get soaked through and take a chill. Until they are fully feathered (about 7 weeks old for Mallard-derived breeds, 8 weeks old for geese, and 14 weeks old for Muscovies), continue providing heat as required by the prevailing weather.

Grown or partially grown waterfowl can be turned loose in a safe yard as soon as you bring them home. If they are of a breed that tends to fly, clip one wing of each bird so it doesn’t take a notion to explore the neighborhood. After your ducks and geese get well acquainted with their digs and learn they will always have plenty of good food to eat, fresh water to drink, and space to play, they will be content in their new home.

Preventing Frostbite

The knobs on the heads of African and Chinese geese, and the large caruncles on the faces of Muscovy drakes, are subject to frostbite, making winter shelter for these breeds essential in cold climates. Suspect frostbite if a bird seems depressed and its knob first turns pale and then patchy. Given time, a knob discolored by frostbite usually returns to normal. To prevent frostbite, confine Muscovies and knobbed geese indoors during icy, cold, blustery weather.

The feet of all waterfowl are susceptible to frostbite, which may occur when ducks and geese congregate around a feeder surrounded by ice or packed snow. The sign of frostbite is pale feet that later turn bright red. Keep the area around feeders clear of ice and snow, or spread sand or straw over the frozen ground. Providing open water for swimming also helps prevent frostbitten feet. Try to keep at least a portion of the pond free of ice, perhaps by installing a recirculating pump.

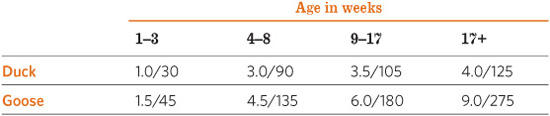

The nutritional needs of waterfowl vary by species, age, purpose, and level of production. Ducks have slightly different needs from geese, growing birds have different needs from mature birds of the same species, and layers and meat birds have different needs from one another.

Under natural conditions, Mallard-derived ducks satisfy 90 percent of their nutritional needs by eating vegetable matter; the remaining 10 percent comes from animal matter, such as mosquitoes, flies, and tadpoles. The diet of a Muscovy leans more toward meat, whereas geese are entirely vegetarian.