For thousands of years, people have raised sheep for three critical reasons: milk, meat, and wool. Of course, other barnyard animals are also able to provide humankind with these items, but sheep have many advantages: They are much easier to handle than larger farm animals, such as cows and pigs. They require little room, they’re fairly easy to care for, and they can be trained to follow, come when called, and stand quietly.

Sheep are also earth-friendly. Land that cannot be used to grow vegetables, fruits, or grains is fine for sheep. They eat weeds, grasses, brush, and other plants that grow on poor land, and their digestive systems are designed to handle parts of food plants, such as corn, rice, and wheat, that people cannot eat. Even just an acre, subdivided into four to six paddocks, will support a small flock of three or four ewes and their lambs during the spring, summer, and fall. Many of the world’s most popular cheeses are made from sheep milk. Sheep manure fertilizes soil.

Our domestic sheep, also known by the scientific name Ovis aries, were first domesticated about 9,000 years ago in an area that corresponds to modern Iraq, Iran, and Turkey. The wild Mouflon sheep, which is considered vulnerable to extinction, is the forebear of our domestic sheep.

Sheep Q & A ............................................................................... 222

Choosing a Breed .................................................................... 223

Buying Sheep ............................................................................ 227

Handling Sheep ....................................................................... 230

Feeding Sheep .......................................................................... 232

Fencing & Shelter .................................................................. 235

Predators & Protection ...................................................... 236

Harvesting Wool ..................................................................... 239

Raising Sheep for Meat ....................................................... 241

Health Care ............................................................................... 243

Sheep rely on their owners for food, protection from predators, and regular shearing, but they require less special equipment and housing than most other livestock. One or two lambs or ewes can be raised in a backyard with simple fencing and a small shelter. Here are some answers to common questions.

Are children safe around sheep? Sheep are among the safest four-legged farm animals for children to handle. Most sheep are small and docile. Rams can be aggressive at times, but sheep, especially those that are around people every day, are usually gentle and even-tempered.

What do sheep eat? Sheep don’t need fancy food. In summer, they can live on grass; in winter, they can eat hay that is supplemented with small amounts of grain. Fresh water, salt, and a mineral and vitamin supplement complete their diet.

Are sheep dumb? Sheep are anything but stupid. They learn quickly and are among the smartest of all farm animals. Many sheep recognize and respond to their individual names. Sheep are often thought to be stupid because of the way they react to perceived danger. They have no way to defend themselves; if an enemy threatens them, they cannot kick like horses, butt like goats or cattle, or bite like pigs. They can only bunch together and run away. Sometimes, when sheep are frightened, they run headlong into obstacles, which makes them seem stupid.

Do sheep stink? Definitely not. All farm animals have their own distinctive odor. The natural odor of sheep and their manure is not as strong as that of cattle, and is comparable to that of rabbits and goats.

How many sheep should I keep? No sheep should be raised alone. Sheep have a built-in social nature and a flocking instinct. They are happiest when they have companions. Orphaned, or bummer, lambs, however, are often just as happy around humans as they are with other sheep. An orphaned lamb quickly becomes attached to the person who feeds it.

How much land do I need to graze sheep? Lambs are a good choice if you are interested in raising meat animals but lack much land. You can raise feeder lambs (lambs fed for butcher) in a pen, allowing about 25 feet (7.6 m) per animal. Although they can be raised in a pen, lambs will do better with access to a well-fenced pasture area. You could raise four or five lambs on just one-quarter acre of grass.

How old should sheep be when I buy them? Most people start with weaned lambs, which are 2 to 3 months of age. You can also buy an older ewe that has been bred to lamb in the spring. These ewes can often be purchased at a low cost, and you’ll get two sheep for your money.

How much do sheep cost? Prices for lambs and adult ewes vary widely. Shop around at several local farms to get a sense of the average market prices in your area. A good crossbred (a sheep whose parents are of different breeds) will be much less expensive than a purebred or registered animal.

Sheep Speak

buck. A mature male; also called a ram.

bummer. A bottle-fed lamb; maybe an orphan, a lamb abandoned by its dam, or a lamb whose dam is not producing enough milk to raise all of her lambs from a multiple birth.

club lamb. A feeder lamb raised as a 4-H, FFA, or other club project.

docked tail. A tail that has been cut short, usually when a lamb is 2 to 3 days of age, for health reasons.

ewe. A mature female.

ewe lamb. An immature female.

feeder lamb. A weaned lamb raised specifically for butcher.

flock. A group of sheep.

hothouse lamb. A lamb born in fall or winter and butchered at 9 to 16 weeks of age.

lamb. A newborn or immature sheep, typically under 1 year of age.

ram. A mature male; also called a buck.

ram lamb. An immature male.

wean. To accustom a lamb to obtain nourishment from feed other than milk; usually takes place around 2 or 3 months of age.

wether. A castrated or neutered male.

Your reasons for wanting sheep will help you determine the best breed for your purposes. Choose a breed whose characteristics are most important to you, whether for meat, wool, or mowing the lawn. Sheep can also be raised for milk, and some famous cheeses—such as feta, pecorino, and Romano—are traditionally prepared from ewe’s milk, but you’d need a lot of sheep to get a sufficient amount of milk for cheese-making. For this reason, a goat or a cow is a much more appropriate choice for backyard milk production.

Your climate will influence the breed you select, particularly if you live in a really wet area or hot climate. Look around and see what breeds of sheep are being raised locally—these breeds may also be the best ones for you.

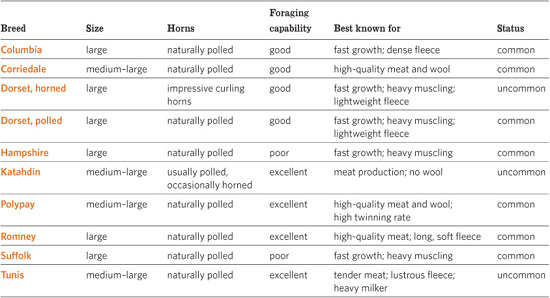

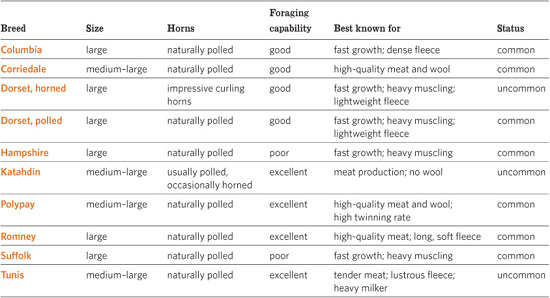

Sheep come in so many breeds that it would take a whole book to describe them all. This section describes some of the most popular breeds, as well as a few minor ones. These brief descriptions will help you decide which breed is right for you.

Columbia. Developed in the United States, Columbia sheep are large animals that produce heavy, dense fleeces and fast-growing lambs. Columbias have a calm temperament and are easy to handle. They have an open (or wool-free) white face and are polled. Mature ewes weigh 150 to 225 pounds (70 to 100 kg); rams weigh 225 to 300 pounds (100 to 135 kg).

Corriedale. Coming from Australia and New Zealand, Corriedales are noted for their long, productive lives and ability to thrive in a wide variety of climates. These large, gentle-tempered sheep have been developed as dual-purpose animals, offering both quality wool and quality meat. A strong herding instinct makes them excellent range animals, as well. They have an open, white face and are polled. Mature ewes 130 to 180 pounds (60 to 80 kg); rams weigh 175 to 225 pounds (80 to 100 kg).

Dorset. One of the earliest breeds of British sheep, the Dorset is considered one of the best choices for a first sheep for both wool and meat. Their lightweight fleece is excellent for hand spinning, and they have large, muscular bodies and gain weight fast. Dorset ewes are good mothers, and Dorsets are one of the few breeds that can lamb in late summer or fall. A Dorset has little wool on its legs and belly, which makes lambing easier. Its face is usually open, and it is white on both the face and the legs. Dorsets are medium size, have a gentle disposition, and may be either polled or horned. Mature ewes weigh 150 to 200 pounds (70 to 90 kg); rams weigh 225 to 275 pounds (100 to125 kg).

Quick Guide to Sheep Breeds

Hampshire. Developed in England, the Hampshire breed is among the largest of the meat types, and the lambs grow fast, making this breed popular for commercial production and 4-H projects. Its face is partially closed; the wool extends about halfway down. It has a black face and legs and is polled. Hampshires have gentle temperaments that make them popular with children. Mature ewes weigh 200 pounds (90 kg) or more; rams weigh 300 pounds (135 kg) or more.

Katahdin. Originating in Maine, the Katahdin is an easy-to-raise meat sheep with hair instead of wool. It does not require shearing, because it sheds its hair coat once a year. Katahdins can tolerate extremes of weather. Except that Katahdins do not produce wool, they possess all the ideal traits for a small flock: They are gentle, with mild temperaments; have few problems with lambing; are excellent mothers; and have a natural resistance to parasites. They have an open, white face and are polled. Mature ewes weigh 120 to 160 pounds (55 to 75 kg); rams weigh 180 to 250 pounds (80 to 115 kg).

Polypay. Developed in Idaho, the large and gentle-tempered Polypay is a superior lamb-production breed with a high twinning rate, a long breeding season, and good mothering ability. Polypays are known for having strong flocking instincts, quality meat and wool, and milking ability. They have an open, white face and are polled. Mature ewes weigh 150 to 200 pounds (70 to 90 kg); rams weigh 240 to 300 pounds (110 to 135 kg).

Sheep Attributes

White or black face. These terms describe the color of the wool on the sheep’s head and face. Normally, the wool on the lower legs is the same color as that on the face.

Open or closed face. These terms are used to describe how much long wool is on the sheep’s face. An open-faced sheep has only short, hairlike wool on its face. A closed-faced sheep has long wool on its face. On a closed-faced sheep, the wool may grow all the way down to the animal’s nose. Too much wool around the eyes causes the sheep to become wool blind. The excess wool must be clipped away so the animal can see.

Prick or lop ear. Just as a German shepherd’s ears stand up and those of a cocker spaniel hang down, a sheep’s ears can stand straight up (prick ear) or hang floppily down (lop ear). Some sheep’s ears stand out to the side.

Horned or polled. Horned sheep have horns. Polled sheep are born without horns.

Open and black face

Closed and white face

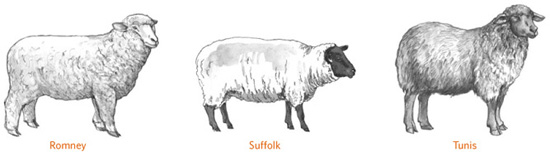

Romney. Coming from England, Romneys are gentle-tempered sheep and excellent around children. They are polled and have an open, white face, black points (noses and hooves), and a long, soft fleece that is ideal for hand spinning. They also produce good market lambs. Romney ewes are quiet, calm mothers. Romneys are best suited to cool, wet areas. Mature ewes weigh 150 to 200 pounds (70 to 90 kg); rams weigh 225 to 275 pounds (100 to125 kg).

Suffolk. Originating in England, Suffolks are by far the most popular breed in the United States for commercial production of meat and fiber and a common club lamb for 4-H and Future Farmers of America. They are similar to Hampshires, being large and having fast-growing lambs. They have an open, black face (unlike the Hampshire’s partially closed face) and are polled. Suffolks are usually gentle, but some can be headstrong and difficult for younger children to manage. Mature ewes weigh 180 to 225 pounds (80 to 100 kg); rams weigh 250 to 350 pounds (115 to 160 kg).

Tunis. Believed to have roamed the hills of Tunisia and parts of Algeria prior to the Christian era, this breed has been around for more than 3,000 years, making it one of the oldest sheep breeds. It is considered a minor breed because relatively few Tunis sheep may be found in the United States. They are medium size, hardy, docile, and good mothers. The reddish tan hair covering their legs and closed faces is an unusual color for sheep. They have long, broad, free-swinging lop ears and are polled. Their medium-heavy fleece is popular for hand spinning. The Tunis thrives in a warm climate, and the rams can breed in hot weather. The ewes often have twins, produce a good supply of milk, and breed for much of their lifespan. Mature ewes weigh 125 to 175 pounds (60 to 80 kg); rams weigh 175 to 225 pounds (80 to 100 kg).

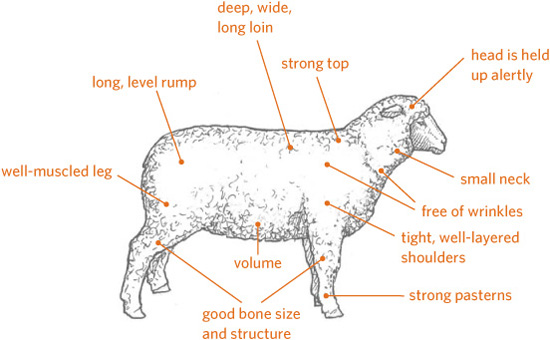

Qualities of a Good Sheep

• Good conformation, with no obvious defects

• Rear legs plump and well muscled

• Teeth meet dental pad well; jaw not overshot or undershot

• Strong pasterns (ankle joint just above the hoof)

• Rams: good fertility (have it checked by a veterinarian)

• Ewes: good udder with no lumps or damage

Top 10 Tips for Health and Happiness

1. Have regular feeding times when you are supplementing your sheep’s diet with grain or hay. Feedings are usually given once in the morning and once in the evening.

2. Stick to the regular diet. If you are going to change feed, do so gradually. Start adding the new feed and reducing the old feed over a period of about 10 days.

3. Provide plenty of fresh water. Water is an important part of your sheeps’ good health, and they will drink more if it is fresh. If manure gets into the water, empty the container and clean it well before refilling it.

4. Lock down the grain supply. Sheep love grain and will try to figure out how to get into the grain storage area. Overeating grain can cause severe stomach upset and possibly death, so keep grain in a tightly lidded container the sheep cannot reach or knock over.

5. Never allow your dog or any other dog to play with your sheep. Sheep are afraid of dogs, and a dog barking at them through the fence or running in the pasture causes sheep severe stress, which can lead to overexertion, heat stress, and heart failure.

6. Watch for external parasites, and treat them immediately if you see any sign of keds, lice, mites, or fly-strike. Seek treatment advice from your veterinarian, county Extension agent, or an experienced local shepherd.

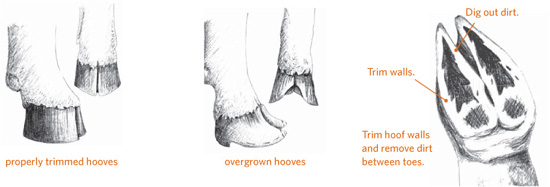

7. Keep hooves trimmed. Sore, overgrown hooves are not comfortable. For more on hoof trimming, see page 243.

8. Treat for worms. Consult your veterinarian or Extension agent for instructions on type and use of deworming medications. For more about deworming, see page 245.

9. Provide shade. Sheep need shade in the summer. An open-sided shed, shade trees, or a canopy roof will keep them cool.

10. Train your sheep to be calm and cooperative when routine handling is necessary. Peanuts and small bits of apple make great rewards and treats.

The breeds that have fallen out of favor with industrialized agriculture are referred to as rare, heritage, or minor breeds. Many of these breeds were major breeds just a generation or two ago, but as agriculture has focused on maximum production regardless of an animal’s constitution, these old-fashioned breeds have begun to die out. The loss of heritage breeds can have an especially grave impact on homesteaders, who are usually interested in low-input agriculture, which means less work on the part of the farmer.

These breeds, although not the most productive in an industrialized system, have traits that make them especially easy to maintain. Some are dual-purpose, able to produce both meat and fiber. Others are acclimatized to regional environments, such as hot and humid or dry and cool conditions. Many perform well on pasture with little or no supplemental feeding. Others resist disease and parasites. Some have such strong mothering skills that they leave you with little to do during lambing season.

Interest today in preserving heritage breeds of livestock, including sheep, is increasing. A driving force in this movement in the United States is the American Livestock Breeds Conservancy (ALBC) and in Canada, Rare Breeds Canada (RBC). For more information about heritage breeds of sheep, contact these organizations or visit their websites.

Try to buy a sheep directly from the person who raised it, because you can ask questions about the sheep’s history and see the flock it comes from. Avoid buying a sheep at an auction; you usually can’t talk with the owner, you may be rushed into making your decision, and you can’t be sure of the animal’s state of health.

If you’re buying a lamb for meat, look for a weaned lamb. Should you buy, or accept the gift of, a bummer lamb or a bottle baby? That depends on how much time you have, and what you intend to do with the animal in the long term—butchering a bottle lamb will be emotionally tough and some people simply can’t do it.

In looking for the ideal sheep, above all it should be healthy. You can gauge a sheep’s condition by examining it carefully for the following characteristics:

• It should seem alert and thriving.

• It should come from a flock with no major medical problems. If the whole flock is healthy, your sheep has probably been well cared for, is of sturdy family stock, and has not been exposed to disease or parasites.

• It should be the normal size and weight for an animal of its age and breed. A large-boned sheep will have more meat, and the ewes will handle pregnancy and birth more easily.

Examine the sheep’s eyes, teeth, feet, and other body parts, including its fleece. Look for signs of good health and conformation, and avoid purchasing a sheep with any of the following problems.

Eyes. Runny, red, or damaged eyes may mean the sheep is diseased.

Teeth. Worn or missing teeth will interfere with eating.

Jaw. The lower jaw should not be undershot or overshot (see the illustrations on page 228).

Head and neck. Lumps or swelling under the chin may be related to bottle jaw, indicating an untreated worm infestation, or to abscesses caused by a bacterial infection.

Feet. A sheep with untrimmed or overgrown hooves has not been cared for properly. If the sheep is limping, it may be injured or have foot rot (see page 243). Even if the sheep you’re considering seems healthy, notice whether other sheep in the flock are limping. If a sheep in the flock has foot rot or other foot problems, your sheep may also be infected.

Body conformation. Sheep with narrow, shallow bodies tend to be light muscled. Sheep with wide backs and deep bodies are more desirable.

Body condition. Don’t choose a ewe that is extremely thin. However, it’s normal for a ewe that has just raised lambs to be thin, which does not mean she has a health problem. Don’t choose a fat ewe, either. She may have trouble lambing.

Potbelly. A thin lamb with a potbelly usually has a heavy infestation of worms.

Udder. If you are buying an adult ewe, check the udder. If it is lumpy, she may have had mastitis, which sometimes causes a ewe to have no milk for any future lambs.

Proper Sheep Conformation

Tail. The tail should be cut short, or docked, which for health reasons should be done to all lambs at 2 to 3 days of age. An extremely short tail, however, is a serious defect in a breeding ewe, as it weakens the tail area and may create problems during lambing.

Manure. Runny droppings or a messy rear end can mean the sheep is sick or has worms. However, a lamb that has been grazing on new, lush spring grass may naturally have runny droppings.

Wool covering. Each breed has a certain amount of wool on its face or legs. Your sheep should have the correct amount for its breed. Avoid sheep with excessive wool around the eyes, which can lead to wool blindness.

Fleece. A ragged, unattractive fleece may be an indicator of disease, keds, or lice (see page 245).

External parasites. Look for any signs of external parasites, including keds and lice.

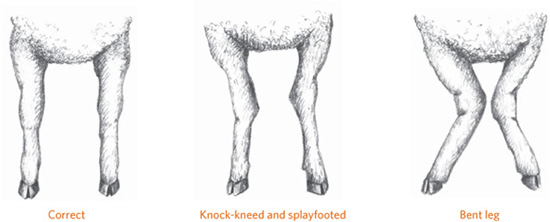

Leg Conformation

Jaw Conformation

Until the age of 5, you can determine the age of sheep to some extent by their teeth. A well-cared for backyard ewe may remain productive to the age of 10 or 12 years, and some hardy individuals live 20 years or more.

The front teeth of sheep are similar to the front teeth of humans, with one big difference: Sheep have front teeth only on the bottom. Where you would expect to find upper teeth, a sheep has a hard gum line called a dental pad.

You can estimate the age of a sheep by examining its teeth. The front teeth of sheep begin to show at 2 to 3 weeks of age, starting with one pair in the center. This pair is followed by three more pairs a few weeks later. The lamb will have eight teeth in all. Sheep lose their baby teeth, and permanent teeth grow in. When the sheep is about 1 year old, the first pair of permanent teeth appears. Each year after that until the sheep is 4 years old, it gains another pair of permanent teeth. When the sheep is 4 years old, all four pairs of baby teeth have been replaced with permanent teeth.

Past the age of 4, the incisors start to spread, wear, and eventually break. When a sheep loses some of its teeth, it’s called broken mouthed. When an aged sheep loses all its teeth, it’s called a gummer.

Don’t be afraid to ask these important questions only the seller can answer.

What vaccinations or treatments has the sheep had, and when? Young lambs may have received some, but not all, of their primary vaccinations. The sequence and timing of the vaccinations are important. You may be purchasing a lamb in the middle of its immunization schedule. You will need to know what shots were given and when so you can get the rest of the shots on schedule and with the same product.

When was the sheep dewormed, and with what? You will need deworming information so you can give scheduled maintenance dewormings using the same product the animal has already received. (For more about deworming, see page 245.)

What kind of feed is the sheep being fed? Any sudden change in the kind of feed you give your sheep can make it sick. Digestive upset can also slow down your sheep’s growth or even cause its death. If you are not sure what to feed your sheep, continue to give it the same kind and amount of feed it has received up to now.

Top Tips for Buying Lambs

• Buy a healthy lamb. Ask your veterinarian to examine the animal for signs of disease.

• Learn to recognize the finer points of conformation. Exceptional conformation may be worth the money.

• Price does not always reflect quality. The most expensive lamb is not necessarily the best one.

• Most faults don’t get better with time. If the lamb has faulty conformation, its defects will become more pronounced with age.

• Don’t buy what you cannot see. Learn how to discern desirable traits, such as a thick leg muscle, by feeling the lamb.

• Spend only 80 percent of what you think you can afford. Expenses you haven’t planned for will always come up.

• An inexpensive lamb with poor conformation is not a bargain. Keep shopping until you find affordable quality.

Was the sheep a twin? Was its mother a twin? Twinning is a highly desirable genetic trait. The possibility of twinning is mostly determined by the ewe. If the ewe is a twin, she is more likely to give birth to twins. However, even if you are buying a ram, ask if he was a twin. If so, his daughters are also likely to give birth to twins.

If the sheep is an orphan lamb, why is it an orphan? A lamb may have been pushed away by the mother because she had triplets or quadruplets, and this one was just one too many for her to care for. But if the ewe was simply a poor mother—some ewes are not as interested in mothering as others are—or had no milk, her daughter may have inherited these traits. The female bummer will therefore be less valuable for breeding when she grows up.

Has the flock had a history of medical problems? Diseases spread quickly in a flock. A sheep from a sick flock may have been exposed to a number of diseases, especially foot problems. Notice whether any sheep in the flock limp or kneel when grazing. If their feet show signs of neglect, such as overgrown hooves, be cautious about buying from the owner of this flock. Along the same lines, don’t buy sheep that show signs of having lice, keds, or problems with internal parasites.

Is there a record of this sheep’s growth? Ask for the date of the lamb’s birth, its weight at birth, the date of its weaning, and its weight at weaning. You can use this information to figure out its rate of growth. A lamb’s rate of growth is more important than its size. Two lambs of equal weight may be two or more months apart in age. If you are raising a lamb for meat, do not purchase a slow-growing runt, because it won’t gain enough to be economical. After you buy your lamb, weigh it frequently and write down the weight on your sheep record.

To be a successful shepherd, you must learn to take advantage of the sheep’s way of thinking. A sheep’s most powerful instinct is, at all costs, to avoid being trapped. A cat has claws, a porcupine has quills, and a skunk has scent, but a sheep has only one defense from danger—she can run to escape.

This drive to avoid being trapped is why dogs in the pasture can cause so much trouble. When the sheep see the dog, they run to escape. When the sheep begin running, the dog thinks it’s fun and begins chasing them. It’s a vicious circle.

Sheep will come to you if you don’t do anything to startle them or make them think you’re trying to chase them. For instance, if you try to drive sheep into a barn, they will avoid going in if they think you are trying to trap them. But sheep love to eat and will do almost anything to get their favorite treat. They especially love peanuts, apples, and grain. If you show them a bucket of grain and use it to coax them to follow you, you can lead them into the barn easily. In fact, they will be so eager to follow you they will get pushy.

Allow the sheep time to eat the grain before you try to pen them or catch one. The grain is their reward for coming in, and eating it should be a good experience for them. Once the sheep are indoors or in a pen, use lambing panels or a gate to squeeze them together so they can’t run away.

Basic Behavior Characteristics

Understanding your sheep’s behavior will be easier if you remember the following:

• Sheep fear noise, unfamiliar surroundings, or unfamiliar items in their surroundings (a jacket hanging on the shovel against the wall, for example), strange people, dogs, and water.

• Sheep move readily from a dark area to a light area, from a confined area to an open area, from a lower area to a higher area, and toward food.

• Sheep like to follow one another and move away from people, dogs, and buildings.

• Sheep will cling to a wall in a pen but will bunch up in sharp corners and stay there.

Hold your sheep with one hand under its chin and the other on its dock.

Sheep in this sitting position will hold still while you shear, trim hooves, and give shots.

Then walk up to the group, catch one sheep, and move it to an area where you can handle it.

If you say a sheep’s name and offer it a treat at the same time, it will soon come when you call its name. You’ll be surprised how quickly it will learn. If you sit quietly on a small stool or box in the middle of the sheep pen, your sheep will be curious about you and begin to approach. Remain still and talk softly; your sheep will soon come close enough to smell your hair and nibble at your clothing.

As your new sheep become tame, they will probably want to be scratched and petted. Never attempt to scratch a sheep on the top of its head or nose; sheep don’t like it. They prefer to be stroked under the chin and scratched on their chest between their front legs. Some sheep like to have their back or rear scratched.

The time will come when you will need to make a sheep do something it doesn’t want to do. By training a sheep properly, you can get it to do such things without becoming frightened or losing its affection for and trust in you.

Although you can train calm adult sheep that are used to people, it’s easier to begin training as early as possible. A lamb that has not been handled much is practically impossible to catch in a pasture. Training should start once the lamb begins to nibble at grass at about 2 weeks of age.

Never hold a sheep by its wool; that hurts. To make a sheep stand still, place one hand under its chin and the other hand on its hips or dock (tail area) and slightly to the rear. When held this way, it can’t go forward or backward, and it can’t swivel away from you. With your hand gripped firmly under the chin, walk your sheep forward by giving it a gentle squeeze on the dock. As the sheep starts moving, all you need to do is keep up with it. When you want it to stop, hold it back with the hand under its chin.

Training should start once the lamb begins to nibble at grass at about 2 weeks of age.

To give a sheep shots, trim its feet, or shear its wool, take advantage of a reflex every sheep has: Once all four of its feet are off the ground, it can be placed on its rump and it will sit still.

To get your sheep into this sitting position, slip your left thumb into the sheep’s mouth in back of the incisor teeth and place your other hand on the sheep’s right hip. Bend the sheep’s head sharply over its right shoulder, and swing the sheep toward you. Lower it to the ground as you step back. From this position, you can lower it flat on the ground or set it up on its rump for foot trimming.

Withhold feed for several hours before handling or shearing sheep. This sitting position is uncomfortable for a sheep with a full stomach.

When a lamb is about 1 month old, begin to train it with a halter. Your sheep will not like its halter at first, but with practice and repetition, it will soon settle down. After the halter is in place, grip it close to the head and place your other hand over or behind the sheep’s hips, just as you would without a halter. Start leading by pulling on the halter and pushing on its rear. Be patient. A lamb may buck and fuss a bit, but it will soon get used to working with the halter.

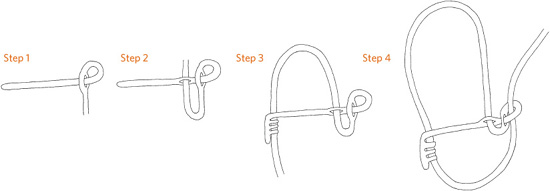

Making a Halter

To make a halter for training and tying up, you will need an 8- to 10-foot (244–305 cm) length of 3/8-inch-diameter (0.95 cm), three-ply nylon rope. Cut the rope by holding it over a flame at the desired length. Slowly rotate the rope over the flame. Once the nylon rope has melted apart, and while the melted nylon is still hot enough to stick together, use pliers to squeeze the ends to seal the nylon strands together. Do not use your fingers; the ends of the rope will be hot. Loop the rope together, as shown in the following steps.

To create holes in the rope, twist the ply open.

Sheep, like goats and cows, are ruminants. They have four compartments in the upper part of their digestive systems that work together to break down plant material such as fresh grass and hay. (See pages 184-85 for a detailed description of the ruminant digestive system.)

Feed for mature ewes and rams consists of grass pasture, salt, a mineral/vitamin supplement, and water. If you are going to breed your sheep you will need to increase their level of nutrition. From the day you bring your sheep home, you will need to provide a constant supply of fresh water. For a few sheep, a washtub works nicely for watering. Do not use a bucket, which is easily tipped over.

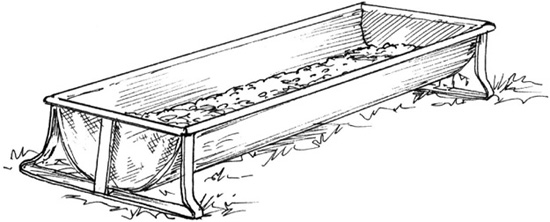

Sheep feed themselves much of the year from pasture grass. In periods of drought, when grass becomes short, or in winter, supplement your sheep’s diet with hay and/or grain. Feed sheep a green, leafy grass or alfalfa hay. Never throw the hay onto the ground, where it will become dirty and wet and contribute to worm infection. Use a feeder.

A supply of salt is important for good health. The salt should be loose or granulated. Never feed sheep a salt block intended for cattle. The sheep may attempt to chew the block and harm their teeth. A good mineral and vitamin supplement is also necessary, and should be of a sort intended for sheep. Cattle minerals often contain levels of copper that can be toxic to sheep. These supplements are usually placed in sturdy wooden boxes that won’t tip over, or in a hanging feeder.

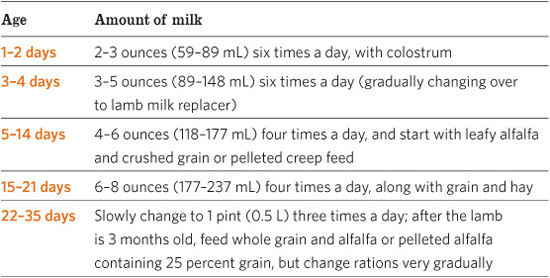

Suggested Feeding Schedule for an Orphan

If you need to change their feed, do so gradually. Sheep cannot adapt quickly to big changes in their diet, such as a change from feeding on pasture grass to feeding on grain. The microorganisms that help digest grass differ from those that digest grain. Therefore, make dietary changes slowly, to give the appropriate microorganisms time to grow in numbers. A grassfed animal needs a week or more before it can digest a large amount of grain.

Bottle lambs take a tremendous amount of effort, but raising them successfully is a truly rewarding experience. They need to be fed frequently, day and night, but in small quantities (see chart above for schedule), and you can’t skip feedings or the lamb may fade away amazingly fast. It is very important that you only feed small quantities of food: overfeeding can cause scours (a severe form of diarrhea). Almost half of all lambs that die are the victims of scours, and bottlefed lambs are particularly prone to this affliction.

Keep bottles, nipples, and milk containers clean, and the milk refrigerated between feedings. Warm the milk immediately before feeding, but don’t get it too hot or it will scald the lamb’s mouth.

If scouring occurs, substitute a day’s feeding with oral electrolytes—give no milk. In a pinch, you can make a homemade electrolyte solution (see recipe on page 202), but ultimately it pays to keep some powdered electrolyte on hand that is specifically prepared for livestock. Such products (those labeled for calves work fine for lambs) contain not only electrolytes but also vitamins, minerals, and energy components. A few teaspoons of Pepto-Bismol or diarrhea medication for human infants can also be used for baby lambs.

Pasture rotation is good for grass growth as well as for sheep health. Use woven-wire fencing or portable electric fencing to divide the area into four to eight smaller paddocks. While the sheep spend a few days grazing one paddock, the grass in the empty paddocks has time to regenerate. With the sheep rotated through smaller pastures, the grass they eat is always fresh.

A feeding trough for sheep.

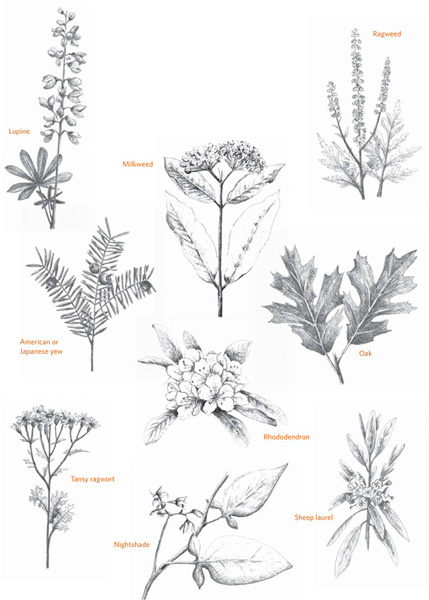

Sheep are curious and love to nibble at strange plants, so you must prevent them from contact with any poisonous plants or shrubs in their grazing area. Your county Extension agent can tell you what poisonous wild plants grow in your area, but you’ll need to investigate potentially dangerous ornamental plantings. The most common plants that are poisonous to sheep are American or Japanese yew, lupine, milkweed, nightshade, oak, ragweed, rhododendron, sheep laurel, and tansy ragwort.

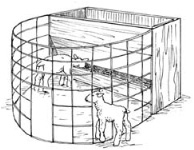

Before you bring your first lamb home, fencing around your sheep pasture should be your first priority. Build a fence if you have none, or check existing fences to be sure they are secure. Fences keep in sheep and keep out predators, such as dogs and coyotes. A dog playing with a sheep in the pasture can kill or seriously injure it, and coyotes prey on sheep. Sheep and lambs need shelter only in bad weather—heat, cold, rain, and snow.

Fences. Of the many types of fence, the best for sheep is a smooth-wire electric or a nonelectric woven-wire fence. Some nonelectric wire fences have six or more tightly stretched wires and heavy posts, but woven-wire sheep fence is better. This fencing is designed not only to keep sheep in, but also to keep predators out.

The strength of the electric fence is in the shock. Electric fence chargers, or energizers, are available at farm supply stores and fence supply dealers. Most of these chargers operate on a few dollars’ worth of electricity per month.

Fences permit you to rotate your pasture. Cross-fence, or divide, your large pasture into smaller paddocks by using inner fences. The outer perimeter fence must be permanent and sturdy to keep dogs out of the pasture, but the inner fences can be made of inexpensive woven-wire or portable electric fencing, which is quick and easy to construct.

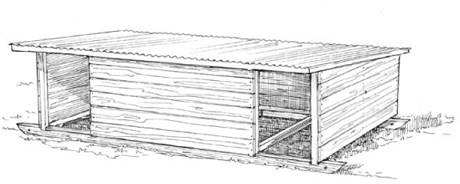

Shelter. When they must seek shelter, sheep are happiest in a south-facing three-sided shed; it’s well ventilated and offers adequate protection from the weather. If your sheep shelter is an enclosed shed, it must be well ventilated. You can build or buy a small portable shed that can be moved easily to whichever paddock the lambs and ewes are currently in. Allow 15 to 20 square feet (1.5 to 2 sq m) per adult animal.

Of the many types of fence, the best for sheep is a smooth-wire electric or a nonelectric woven-wire fence.

A portable structure provides flexibility and inexpensive shelter for sheep and lambs on pasture. Because sheep use the shelter only in bad weather, up to six ewes and their lambs can share one shelter.

Whatever sort of shelter you have, keep it clean. If you think it smells bad, so will your sheep—and the dirty shelter will be a potential breeding ground for disease.

Even good fencing can’t always provide enough protection for sheep at night. The shelter should be located within a corral or small pen constructed of tightly woven wire or cattle panels that will positively keep dogs and other predators from getting to the sheep. If you place feed in the shed each evening, the sheep will naturally head toward it every night.

Sheep Manure

Use sheep manure as fertilizer in your garden. If you don’t have a garden, you can sell packaged manure to gardeners in your area. Sheep manure is dry, has little odor, will not burn plants, and is an excellent substitute for commercial fertilizer. Sheep manure also has more nitrogen, more phosphorus, and more potassium than cow manure.

Predators are a potential problem for all shepherds. But not all predators kill sheep, and predators are important members of the food chain, creating a balance that nature depends on. Predators keep populations of wild herbivores, such as deer and elk, from overpopulating their ecosystems, and they feed on lots of small rodents and rabbits. They’ll also eat insects and carrion, which is often abundant along highways.

Predator species tend to be opportunistic animals, seeking the easiest target to meet their needs. In other words, they usually go for young, old, weak, or sick animals first, though some have been known to attack mature, healthy animals in their prime. All predators become more aggressive as their hunger increases—during a drought, for instance—and may attempt to take anything they can sink their teeth into.

As a shepherd, you can learn to manage your flock so a predator will decide that eating at your place is a lot more difficult than chasing mice and rabbits. The box on page 237 will give you some ideas on how to minimize predation. Keep in mind that your sheep are less likely to suffer from predation if they are strong and healthy; good feed and adequate health care pay in more ways than one.

Although coyotes kill more sheep than dogs do, more shepherds experience predation by dogs. Bears and wildcats can also create nightmares for a shepherd, and occasionally birds of prey (eagles and hawks) and carrion birds (vultures and ravens) may be the culprits.

Sometimes predators get a bum rap: If the corpse of a dead sheep has obvious bite marks, it’s natural to think a predator was the perpetrator. But sheep die from a number of causes, and unless you see a predator attacking a live animal, the sheep may have died of natural causes and then been fed on by scavengers.

Coyotes. Wile E. Coyote may have looked the fool in all of his encounters with the Road Runner, but he’s not a good example of the species. Coyotes are intelligent, curious, and adaptable and they have been expanding their range into urban and suburban areas of the United States.

Coyotes generally select lambs over adults, unless hunger has made them desperate. Smaller lambs and those born to young, old, or crippled ewes are more commonly victims than those of middle-aged and healthy ewes. And a coyote is more likely to take the smallest lamb from a set of twins or triplets than to take a larger, single lamb.

Dogs. Dogs are a special class of predator for shepherds. An estimated 62 million or more owned dogs in the United States—not counting countless feral and abandoned dogs—means that for every sheep more than six dogs are roaming around. And they can prove more dangerous than coyotes, as one or two dogs can maim or kill dozens of sheep in one night. Many people have been driven out of the sheep business because of dogs.

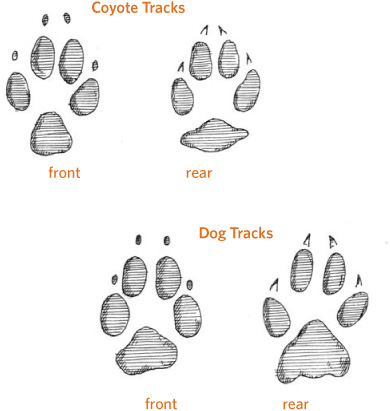

The coyote track is about 3 inches (7.5 cm) long for the front foot, and 2½ inches (6.3 cm) for the rear. Dog tracks can vary from slightly larger than a coyote track to quite a bit smaller, depending on the size of the dog. Notice that the pads vary. If you live where wolves present predator problems, look for a doglike track that is about 5 inches (12.7 cm) long in the front.

Predators can be discouraged by the following techniques:

• Keep guardian animals, like dogs, donkeys, or llamas.

• Use a lighted night corral with a high, predator-tight fence.

• Put high-frequency bells on some of your sheep; you can hear the bells if the sheep are being chased, and predators are less likely to chase sheep that are wearing bells.

• Keep your sheep in an open field in sight of your house.

• Use coyote snares along fence lines to catch both dogs and coyotes. First check the legality of using snares in your area.

• Have a gun and know how to use it. Even a pellet gun can drive off an attacking dog. A dog running through a flock of sheep is not an easy target, but like most predators a dog will spook at the sound of a gun shot into the air.

• Use a live trap, which is a cage that allows the trapped animal to be set free. Such traps work well with dogs but are of little value with coyotes because they are too wily to be caught. State wildlife officers may supply live traps for bears or wildcats that are repeat offenders.

• Use a propane exploder (which produces a loud explosion), a radio, or other noise-making device and frequently change its placement, volume, and timing to prevent predators from getting used to the device and losing their fear of it.

• Use a combination strobe light and siren, a device developed and tested by the USDA that seems to significantly reduce predation.

Fido and Spot don’t have to be wild, vicious, or even brave to chase sheep. When dogs chase sheep, they’re following their natural impulse to chase whatever runs. Unfortunately, sheep run at the slightest disturbance. The offending dogs are not as much at fault as owners who don’t keep their pets at home.

Dogs attack rather indiscriminately—they grab at any part of a sheep they can. Sheep often survive dog attacks but may be badly injured. Even dogs that are too small to kill or maim a sheep can still cause heart failure in older ewes and abortion in pregnant ewes. Broken legs may also result when dogs chase sheep.

Other predators. For most shepherds, wolves and foxes are less problematic than coyotes, though both are similar to coyotes in their style of predation and feeding. Wolves tend to hunt in packs of two to four animals and can easily take down adult sheep. Because of their small size, foxes take only fairly small lambs.

Bears and wildcats (mountain lions, lynx, or bobcats) are common in more remote areas, especially in the West. These animals can kill perfectly healthy, strong adult sheep as easily as they can a young or an old sheep. They often kill more than one animal in a single attack and then feed on their favorite parts of each kill.

Cats generally attack by biting the top of the head or neck. Bears usually use their massive paws to strike a sheep down. Eagles and other birds of prey occasionally kill lambs. They attack by dropping out of the air at high speed and closing their talons into the head.

Many wild predators are protected or controlled by federal or state laws and regulations. If you have, or suspect you have, a problem with wild predators, call the Wildlife Services office of the United States Department of Agriculture or your state’s wildlife office to learn about specific remedies and laws in your area. In Canada, the Livestock, Poultry and Honey Bee Protection Act provides for compensation for sheep producers who lose animals to predators; contact the Ministry of Agriculture in your area to learn more.

Your county Extension agent should be able to tell you the county’s dog laws or, better yet, give you a copy of the county or state laws. You may find they are strict and well spelled out but lack enforcement.

Some states permit the elimination of any trespassing dog that is seen molesting livestock. Others require the owner to have the dog destroyed or be charged with a misdemeanor. Most states allow the livestock owner to recoup payment from the dog’s owner (if known) for both damage and deaths to livestock. If a dog is chasing or killing sheep, promptly contact your local sheriff or animal-control officer. They can assist you in determining the dog’s owner and can impound the dog and press charges against the owner on your behalf.

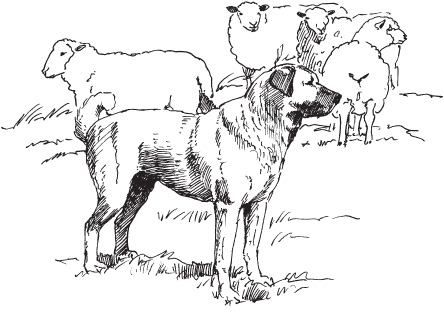

Sheep have been bred for thousands of years to be docile, a trait that makes them easy victims. However, other species become quite aggressive when predators invade their territory, and shepherds have harnessed this trait to defend their sheep for almost as long as sheep have been domesticated.

Attacks usually occur at night or early in the morning when you’re normally asleep. A guardian animal is on duty 24 hours a day and is most alert and protective during the hours of greatest danger.

Few guardian animals actually kill predators, but their presence and behavior can reduce or prevent attacks. They may chase a trespassing dog or coyote but should not chase it far. Chasing for a prolonged distance (or time) is considered faulty behavior because the guardian should stay near the flock, between the sheep and danger. The best guardians balance aggressiveness with attentiveness to the sheep.

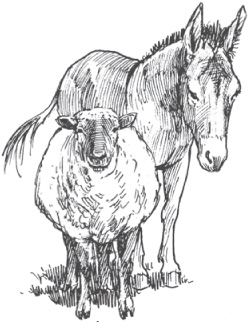

Dogs, ponies, llamas, donkeys, mules, and cows are all used as sheep guardians. Even geese have been used to guard sheep, although they’re more effective against domestic dogs than against wild predators. Whichever type of guardian you’re considering, remember the following:

• The guardian needs to bond with the sheep, and the bonding process can take time.

• Guardians should be introduced slowly, across a fence; it’s usually easiest to make the introduction in a small area rather than in a large pasture.

• One guardian is generally sufficient except on open range, where at least two are required. In a large pasture or on open range, bigger animals (such as donkeys and llamas) may be more effective than guardian dogs—though dogs can significantly cut down on losses, even in large areas.

• Each animal is an individual and wil react differently in different situations. Some individuals don’t make good guardians.

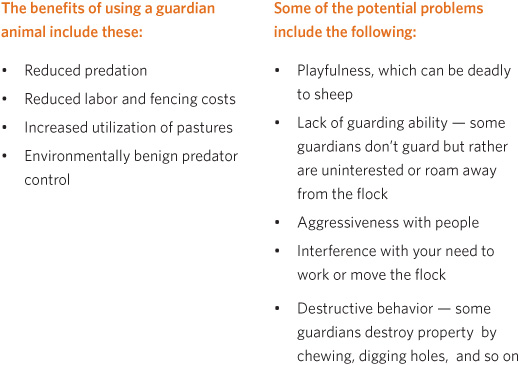

Guardian Pros and Cons

Although guardian animals can be a great help to a shepherd, keeping them may have some drawbacks as well.

A donkey will usually bond with sheep and protect them from predators.

Different breeds of dog are suited for different circumstances, requiring careful selection to best suit your sheep-guarding needs.

With the exception of hair sheep, which have little or no wool, sheep must have their wool sheared off annually. Shearing is usually done in the spring so the sheep are free of their heavy wool coats for the hot summer months. Shearing is important for keeping your sheep healthy and comfortable. This annual haircut has the additional benefit of producing wool, which you can either spin yourself or sell to handcrafters.

Many people raise sheep for the single purpose of supplying themselves with wool. You can dye and spin the wool yourself to make yarn with which to knit sweaters, socks, mittens, hats, and many other projects. Or, you may decide to felt your wool. By employing the technique of wet felting, you can make scarfs, hats, mittens, and many other products; or, use needle felting to create toy animals and other felted objects. For more information on the type of wool produced by each of the wool sheep breeds, refer to The Fleece and Fiber Sourcebook by Carol Ekarius and Deborah Robson.

Even if you are not a spinner or felter you can profit from your fleeces. You might sell them to a wool pool, which combines and processes fleeces from many sources. However, selling good hand-spinning fleeces directly to individual spinners can bring in considerably more money. If you earn a reputation among spinners for having prime-quality fleeces, your fleeces will be in demand far ahead of shearing time.

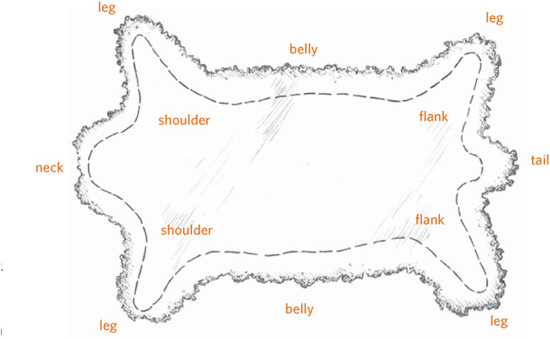

Fleece Quality

Several characteristics determine the quality of a fleece, including wool type, strength, and lack of vegetation. The type of wool—silky, curly, or coarse, for instance—is a characteristic of the breed. The strength of the wool is determined by health and nutrition. But even if your sheep has a strong fleece of a desirable type, it will be less valuable if it is not kept clean. To keep a fleece clean, use a sheep coat to protect it from vegetation, such as seeds, hay, burrs, and bedding. (See page 240 for how to make your own sheep coat.)

The first shearing you observe may be quite a surprising scene—a sheep must be held in awkward positions while its fleece is removed with sharp clippers or shears. While sheep don’t enjoy the process, they feel a lot better after shearing. They’re happy to be rid of their heavy winter coat of wool, and shorn sheep are easier to keep free of external parasites. To reduce the stress for both sheep and shearer:

• Don’t give sheep food or water for about 12 hours (or overnight) before shearing. A sheep with an empty stomach is more comfortable during shearing.

• Be sure your sheep is dry. If rain is predicted, keep the sheep indoors the night before.

• Get your sheep into a pen where each one can be caught easily. A shearer must not be expected to chase or catch your sheep.

• Prepare a good shearing floor. A smooth plywood platform is better than a dirt floor or grassy area.

Spread a tarp or an old wool rug on the platform to make it less slippery.

• When shearing is done indoors, provide sufficient light.

• Have cold water or another beverage available for the shearer.

• Arrange a skirting table, which is a raised table with a slatted top. When you skirt the fleece (remove a strip about 3 inches (7.5 cm) wide from the edges of the fleece), the skirtings (the trimmed-off edges) will fall through the table to the floor. Sanded lath, long dowels, or 1-by-2-inch lumber set on edge makes a tabletop suitable for skirting.

• Have first-aid supplies on hand in case a sheep or the shearer is severely cut. Don’t worry about little nicks on sheep. They may look bad, but the lanolin in sheep’s wool helps them heal quickly. In hot weather, spray each shorn sheep with a fly repellent before releasing it to prevent infection in the tiny cuts.

• Handle the fleece carefully, so it doesn’t become contaminated with manure, straw, or dirt. Sweep the floor after each sheep.

• Shearing is a good time to trim hooves, check udders, deworm, treat for parasites (after the wool is removed), and check the teeth of oldsters. Have all the necessary supplies on hand.

After each sheep is shorn, set the fleece sheared side down on the skirting table. (This position will shake off any second cuts—undesirable short clumps of hair resulting from imperfect shearing.) Then sweep the floor of the shearing area so that the shearer can get going on another sheep.

Skirt the fleece, allowing the cuttings to fall through the slats of the skirting table onto the floor. Roll up the fleece and secure it with paper twine (available from sheep supply stores) or place it in a paper feed sack (turned inside out) or a cardboard box.

Skirt a fleece at the dotted line.

A sheep coat—also called a blanket, cover, or rug—is used to keep a fleece clean while it is still on the sheep. In areas with severe winters, coats help sheep stay warmer, and the energy that might have gone toward keeping them warm is expended on increased wool growth and heavier lambs. Many owners of small flocks who depend on the sale of choice fleeces use coats on all their sheep.

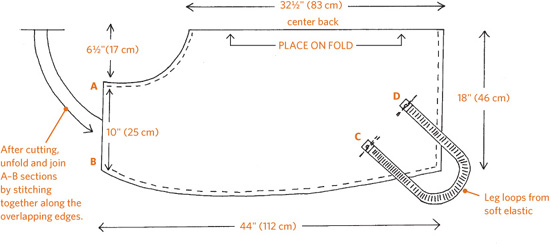

You can make inexpensive sheep coats from woven-plastic feed sacks, which allow air circulation and hold up well. The edges must be well hemmed so that they don’t fray. The easiest material to work with, however, is #10 cotton duck. Prewash it before constructing the coat to prevent shrinkage after the coat is made.

Use the dimensions suggested on page 241, or measure your sheep and make a custom-fitted garment. For the best protection, the coat should extend 3 inches (7.5 cm) below the belly. If your material isn’t wide enough to cut on the fold, cut the two pieces and make a seam along the center at the backbone. To custom fit, determine the coat length by measuring from the center of your sheep’s breast to the end of the back thigh. Make the hind leg loops of soft pajama elastic, which is about 1 inch (2.5 cm) wide and not as stiff as most elastic. Although the garment itself should last more than one season, the elastic will probably have to be replaced each season. Check the sheep often to be sure the elastic isn’t rubbing its leg and causing injury.

To get the right fit, first make a rough model out of an old sheet and try it on your sheep. The front edge should be as close to the head as possible for maximum protection against hay and weed seeds. If you make a center back seam, you can get a closer fit by shaping the seam to conform to the curve of the sheep’s back.

1. To make neck openings, match section A-B on both sides (see illustration on next page) and overlap ½ to 3 inches deep (1.3 to 7.5 cm), depending on the size of the sheep and stitch.

2. Make a ½-inch (1.3 cm) hem on all outside edges (shown by dotted line).

3. At points C and D on both sides, attach loops of soft elastic, each 24 to 27 inches (61 to 69 cm) long, depending on the size of the sheep.

Using these measurements, make a pattern to size (from brown paper), then place on fold of material and cut. Finish following instructions on opposite page.

If you live in an area that has lots of shepherds you should have no trouble finding a weaned lamb, but in many areas of the country finding lambs may be a challenge. The prices for weaned lambs vary across a pretty wide spectrum—you might pay less than $50, or you might be counting out hundreds of dollars.

Club lamb producers specialize in raising lambs to weaning, and then selling them to kids participating in 4-H and FFA (Future Farmers of America) programs at school. Club lambs are typically sold to the young person 120 days prior to their first major show (often the county fair), weighing 60 to 80 pounds (27 to 36 kg). Depending on the breed, they will weigh 110 to 140 pounds (50 to 64 kg) at show time. Your Cooperative Extension office should have information on club lamb breeders in your area.

It may be worthwhile to regularly check Craig’s List on the Internet, as sometimes you can find really excellent animals. If possible, buy from someone close by. Ask lots of questions—if the seller doesn’t want to answer all of your questions, you may want to keep looking.

Can you save money buying a couple of lambs, raising them through the summer, and putting them in the freezer in the fall? Since a weaned lamb will thrive on pasture and water, your main expense (after housing and fencing) is the cost of the lamb. If you buy a 60-pound (27 kg) weaned lamb for $50 and butcher it at 120 pounds (54 kg), you can expect about 30 pounds (14 kg) of meat, giving you an approximate cost per pound of about $1.65, which is a good deal no matter what you’re paying for lamb now. But if you purchase higher-end lambs from the club market, or purebred lambs that are aimed at the breeding-stock market, you could end up losing money.

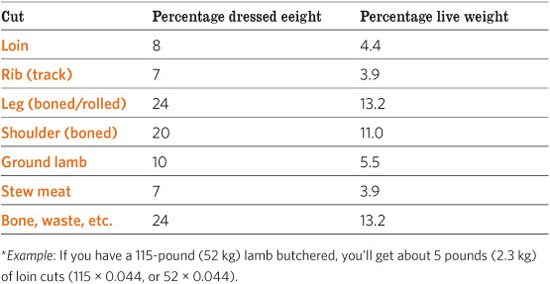

Dressing percentage represents the comparison of carcass weight to live weight, with carcass weight being taken from an animal with hide, internal organs, and head removed. Locker lambs are often sold based on their dressed weight. Yield, or the amount of packaged meat you receive after the carcass is cut and wrapped, typically represents 50 to 60 percent of the dressed weight. The actual percentage for both dressed weight and yield varies based on the condition of the animal, its breed, its bone structure, and the amount of fat it is carrying. For example, if you take in a 100-pound lamb for butcher, typical dressed weight is around 50 pounds, and typical yield is 25 to 30 pounds.

Relative Percentages of Various Lamb Cuts*

Here are some important terms to know if you are interested in raising lambs for slaughter: market lambs have a live weight of 90 to 120 pounds (41 to 54 kg) and their average dressing percentage is 50 percent; hot house lambs have a live weight of 40 to 60 pounds (18 to 27 kg) with a 55 to 70 percent dressing percentage (they’re popular for Christmas and Easter); and cull sheep have a great variety of live weights, widely based on age and condition, and they have a 37 to 52 average dressing percentage.

To get the best quality and best-tasting meat you need to keep the lambs growing at a steady and strong pace. If they are set back by poor feed or health problems the meat’s quality will suffer. Young lamb is naturally expected to be tender, but several factors, one at a time or combined, can reduce tenderness:

• Stress imposed on animals prior to slaughter, such as rough handling when they are caught and loaded.

• Slow growth rate—one good reason to feed your lambs grain in a creep feeder if your pastures aren’t in top form.

A creep feeder allows lambs to enter and eat extra feed, while keeping larger animals out.

• Slow freezing of meat, causing it to dry out; most cut-and-wrap facilities freeze meat faster than you can do it in your home freezer.

• Length of time in freezer storage; one year is the maximum lamb should be stored.

• A lamb can be cut and wrapped quickly after slaughter, but a yearling or mature animal must be tenderized by hanging it for at least one week in a chilling room prior to cutting and wrapping.

You can take your sheep to a custom packing plant to be slaughtered and butchered or you can do it yourself. If you want to do it yourself, get a copy of Basic Butchering of Livestock and Game by John Mettler, DVM, which provides excellent slaughter and cutting instructions, with lots of illustrations to help along the way. Your county Extension agent may also have a booklet available on the topic.

If you’re going to work with packers, you will have to give them some directions. To get the maximum use and enjoyment from your sheep, give these instructions:

• Cut off the lower part of the hind legs for soup bones.

• The hind legs can be left whole, as in the traditional French-style leg of lamb, or cut into sirloin roasts or steaks and leg chops or steaks.

• The loin can be cut as tenderloin into boneless cutlets or as a loin roast.

• Package riblets, spareribs, and breast meat into 2-pound (0.9 kg) packages. The spareribs and breast can be barbecued or braised; for tips on cooking riblets see sidebar on page 243.

• The rack, or rib area, can be cut into that favorite, lamb chops, or left as a rack roast. The shoulder can be cut into roasts or chops, and the neck and shank can be used as soup bones. Stew meat or ground lamb can also come from these front cuts.

• If you want kebab meat, have it cut from the sirloin or loin.

Riblets, which are sometimes referred to as short ribs, are almost inedible when prepared by most cooking methods but when prepared in a pressure cooker for about 45 minutes, with an inch (2.5 cm) of water in the bottom to start, the meat will fall off the bone. You can substitute barbecue sauce, curry sauce, or your favorite sauce or marinade for the water.

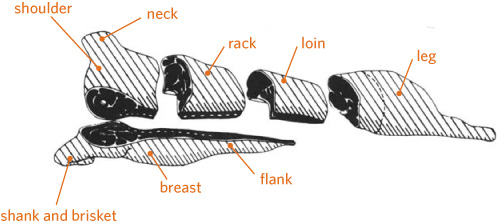

Correctly breaking a lamb carcass can be done in one of several ways, and no one method can be considered best. However, for many purposes, the method shown here is ideal. (From Lamb Cutting Manual, American Lamb Council and National Livestock and Meat Board)

All sheep need grooming, health care, and medical treatment. The basics for keeping sheep in good health include hoof trimming and guarding against hoof problems, vaccinating sheep against diseases prevalent in your area, regular deworming, and protecting your sheep from external parasites.

Wild sheep and those that graze on mountainous pastures wear down their hooves by traveling over rocky ground. Domestic sheep walk primarily on soft soils. Consequently their hooves become long and overgrown, which makes walking painful. Sheep need to have their hooves trimmed so they can walk properly and to help prevent hoof disease, such as scald and foot rot (see below).

Before buying an adult sheep, take a good look at its feet. Ask when they were last trimmed. If they show any need for trimming, the owner should be able to demonstrate the procedure for you. If the owner can’t show you how, don’t buy the sheep—the sheep’s hooves have probably not been properly cared for.

How often to trim your sheep’s feet depends on your pasture, paths, and barn floor. Many shepherds trim twice a year, whereas others need to trim only once a year. If you notice limping sheep or sheep on their knees, check their feet. Whenever you take care of other needs, such as deworming or shearing, make a habit of trimming the animal’s hooves as well.

Wear leather gloves while trimming hooves—a kicking sheep that is not held firmly or properly can injure you with the sharp edges of the freshly trimmed hoof. Set the sheep or lamb on its rump as shown on page 231. Trim the rear feet first, and then the front feet.

Foot problems are some of the most common problems a new shepherd needs to look for. Fortunately, they are generally easy to spot.

Foot rot, a bacterial condition that causes hard-to-cure infections, is one of the worst diseases that can infect your sheep. Active outbreaks of foot rot occur during warm, wet weather. Foot rot is a painful disease; the bottom of the sheep’s hooves literally rots off, exposing the soft tissues beneath.

Before buying a sheep, look at the rest of the flock. If you see any limping sheep or sheep with severely overgrown, misshapen hooves, go somewhere else. Foot rot can be introduced into a clean flock only by an infected animal or a carrier animal (one that shows no symptoms but spreads the infection to others). Once foot rot is introduced into your flock, it is almost impossible to get rid of.

When bringing a new sheep into your flock, a good precautionary measure is to disinfect its feet. To disinfect a sheep’s feet you must walk the sheep through a germicidal footbath—the same as used to treat foot scald (see page 244).

Plugged toe glands occur when the deep gland between the two toes of a front foot becomes plugged, causing swelling and lameness. Look for a small opening at the top of the front of the hoof. The gland secretes a waxy substance that has a faint odor; its purpose supposedly is to scent the grass to reinforce the herding instinct. When the gland becomes plugged with mud, the secretion is trapped, and the toe swells and causes lameness. To unplug a toe gland, squeeze it so the plug pops out. Then clean the area with warm soapy water and disinfect it with a povidoneiodine (Betadine) topical antiseptic.

Trimming Hooves

Many styles of hoof shears are available, but few are as easy and safe to use as Felco No. 2 pruning shears. Many farm and garden stores sell them. If you have many sheep to trim, the investment is well worth the money.

Foot scald is a skin infection that occurs between the toes that occurs most commonly after a long, wet period. The first sign of scald is limping. Usually the front feet get sore before the hind feet do. The skin between the toes is moist, hairless, and red from irritation. Begin treatment by moving the affected animal to a clean, dry area. Trim hooves and then spray them with hydrogen peroxide. If you see no improvement within 72 hours, treat with a zinc sulfate footbath, which can be done using either a large fruit-juice can or booties made for the purpose and available from your veterinarian or any source of sheep and goat supplies. The procedure is as follows:

1. Pour the footbath solution to a depth of 2 inches (5 cm) into the fruit-juice can, or place a bootie on the affected foot and fill it with the footbath solution.

2. Soak the affected foot for 30 minutes.

3. Repeat once or twice a week until the foot scald is resolved.

Lambs should be vaccinated at an early age. Consult your veterinarian, a county Extension agent, or an experienced shepherd about vaccinations for your sheep.

Sheep are commonly vaccinated against diseases that infect the lungs, the digestive system, and the reproductive tract. For example, lambs (as well as ewes and rams) can be vaccinated to protect them against pneumonia, and all lambs should receive immunizations against enterotoxemia, a clostridial disease caused by overeating. Ewes should be vaccinated or given booster shots for clostridial diseases before lambing. This vaccine not only protects the ewe but also increases the disease-fighting antibodies she passes on to her newborn lambs when they nurse. Take this opportunity to vaccinate your ram, too; you will be less likely to forget any sheep if you do them all at once.

Possible Causes of Lameness

• Overgrown, untrimmed hooves

• Mud, stone, or other matter stuck between the toes

• Plugged toe gland

• Abnormal foot development (an inherited defect)

• Foot abscess

• Foot scald

• Foot rot

• Thorns, punctures, bruises, or other injuries

Disease control programs can be somewhat complicated. The important thing to remember is that most vaccinations must be given either before breeding or before lambing. Don’t wait until the ewes are almost ready to lamb before you vaccinate them.

Keep regular records of your sheep’s health history, including dates and vaccinations given.

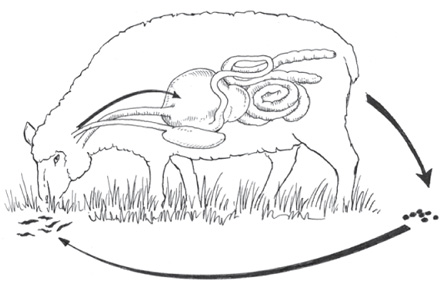

Sheep have a high resistance to disease but low resistance to internal parasites. All sheep, especially lambs, must be dewormed. Sheep can pick up many types of worms through grazing. The worms are microscopic and live off the blood of the sheep. Lambs can die of severe worm infection.

When you raise sheep for the first time, your pasture is probably uncontaminated by previous use. Cross-fencing and pasture rotation help reduce exposure to worms. Clean feeding facilities further help prevent rapid or serious buildup of stomach worms.

Even with precautions, however, sheep can become infected with worms, and they need to be treated periodically. Deworming is especially important in mild climates or after a particularly mild winter. Several good deworming medicines are available that are safe even for pregnant ewes and small lambs. Obtain deworming medicine from your veterinarian, who can give you information on the proper dose and timing. The medicine may come in the form of a bolus (large pill), which is placed on the base of the sheep’s tongue by using a bolus gun, available at farm supply stores. Deworming medications also come in the form of liquid drenches, pastes, feed blocks, and injections.

Symptoms of worms. A lamb with worms may be underweight for its age and have a potbelly, prominent hip bones, a scruffy wool coat, runny or loose manure and manure buildup on its rear, and anemia, which makes it weak. Anemia can be prevented by deworming lambs when they are 2 or 3 months old. If you have only one or two sheep on clean pasture, you may need to deworm your lambs only once more during the first year. In a larger flock that has limited or contaminated pasture, the lambs may have to be dewormed monthly. Adult sheep with heavy worm loads will sometimes have a swelling under their throat or chin called bottle jaw. Ewes should be dewormed before breeding, before lambing, and before going out on fresh spring pasture.

Most internal parasites have a similar life cycle. Sheep ingest worm larvae while eating and pass eggs in their manure. The eggs hatch in the soil, and the larvae migrate onto the grass.

After deworming. Keep your sheep in the last pasture they grazed prior to being dewormed, then transfer them to a clean pasture 24 hours later. The sheep will expel the worms and eggs in the old pasture and won’t contaminate the new pasture as rapidly; worm control is one important reason to cross-fence pasture. The eggs and larvae of many worm species can survive out on pasture for as long as three months in cool, damp weather but may die within three weeks during hot, dry weather.

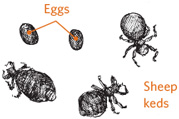

Sheep are subjected to a number of external parasites, including keds, lice, mites, and maggots from fly-strike. If they seem to be bothered by flies, act itchy, or have broken and patchy wool, they are suffering from external parasites. Your veterinarian, county Extension agent, or an experienced local shepherd can offer helpful advice on causes and treatments.

Sheep can be affected by other health problems, such as abscesses, copper toxicity, Johne’s disease, sore mouth, pneumonia, and scrapie. Some illnesses show no signs, and others present symptoms fairly early. If you notice changes in the appearance of a sheep’s skin or wool, difficulty breathing, or intense itchiness, contact your veterinarian.

Keds

Keds are wingless flies that cause severe itching and discomfort. Your sheep will stay free from keds unless you bring in an infected animal or let your sheep come into contact with infected animals.