Raising a milk cow, or a calf or two for beef, is an efficient way to produce food, since cattle can mow the hillside behind your house that is too steep for a garden or survive on a back forty that has too much brush, rocks, or swamp to grow any crop other than grass. Cattle provide us with meat or milk while keeping weeds trimmed, which is a good measure for fire control and yields a neater landscape. Getting set up to raise cattle often does not involve much expense, except for the initial fencing to keep them where you want them. And if you don’t want to bother with purchasing hay and grain, you can use weaned calves to harvest your grass during the growing season, then send them for butchering when the grass is gone—thus making seasonal use of pasture and creating a harvest of meat.

Raising cattle can be a soul-satisfying experience. They are fascinating and entertaining animals; working with cattle is never boring. It can be physically challenging at times, as when delivering a calf in a difficult birth or trying to catch an elusive animal. But for those of us who enjoy raising cattle, the chores of caring for them are not really work. Our interaction with these animals is part of our enjoyment of life.

When you raise cattle, you participate in one of the oldest known human activities. Humans have lived with cattle since prehistoric times. Wild cattle were the main meat in the diet of Stone Age people. Our prehistoric ancestors began to domesticate cattle about 10,000 years ago to have a supply of meat for food and hides for leather clothing. Later humans discovered they could hitch these animals to a cart or a plow. In fact, oxen were used for transportation before horses were; cattle were domesticated sooner than horses, probably because they were easier to catch.

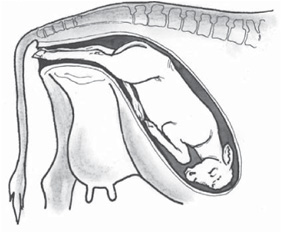

Getting Started ........................................................................ 272

Choosing a Dairy Breed ...................................................... 274

Choosing a Beef Calf ............................................................. 279

Understanding Cattle Behavior .................................... 283

Housing & Facilities ............................................................. 284

Feeding & Watering .............................................................. 289

Feeding an Unweaned Calf ............................................... 292

Weaning Your Calf ................................................................. 296

Butchering Beef Cattle ....................................................... 298

Care of the Milking Cow .................................................... 299

Milking a Cow .......................................................................... 300

Rebreeding Your Cow .......................................................... 302

Get Ready for Calving .......................................................... 305

When the Calf Is Born ......................................................... 306

Calf Management Procedures ......................................... 313

Keeping Your Cattle Healthy ........................................... 314

You can raise a steer in your backyard in a corral or on a small acreage, or you can raise a herd of cattle on a large pasture, on crop stubble after harvest, or on steep, rocky hillsides. Cattle can be fed hay and grain or can forage for themselves. Economics and individual circumstances will dictate your methods. If you have pasture, all you’ll need is proper fencing to keep the animals in, so they won’t visit the neighbors.

You will need a reliable source of water and a pen to corral the animals when they need to be handled for vaccinations or other management procedures. If you have a milk cow, you may want a little run-in shed or at least a roof, so you can milk her out of the weather if it’s raining or snowing. Most of the time, cattle don’t need shelter; their heavy hair coat insulates them against wind, rain, and cold. In hot climates, however, shade in summer is important. A simple roof with one or two walls can provide shade in the hottest months and protection from wind and storm in winter.

As a novice cattle raiser you may need advice from time to time from a veterinarian, cattle breeder or dairyman, or your county Extension service agent. Don’t be afraid to contact an experienced person to ask questions or request help.

Your choice in a calf will depend on how much space you have and whether you want to raise a steer to butcher or a heifer that will grow up to be a cow. A calf can be raised in a small area, even in your backyard if your town’s ordinances permit livestock. But if your goal is to have a milk cow that someday will have a calf of her own, she’ll need more room.

If you are raising a calf to butcher, you should probably raise a steer. Steers weigh more than heifers of the same age. However, heifers are more flexible—you can raise them as beef or keep them as breeding or dairy animals. Mature dairy heifers are worth more money than beef cattle. If you want to eventually raise a small herd of cattle, choose a heifer to start with. Her calves will become your herd.

Meet the Cattle Family

Cattle are of the order Artiodactyla, consisting of hoofed animals with an even number of toes. Most large land mammals are Artiodactyls, including goats, sheep, and pigs. Cattle are in the family Bovidae, consisting of animals with hollow horns. This family includes antelopes, goats, and sheep. The genus is Bos, the true cattle, of which there are two species:

B. taurus: descendants of British and European breeds, as are most cattle in North America

B. indicus: cattle with large ears and humped backs, which are especially adapted to hot climates, such as the Brahman

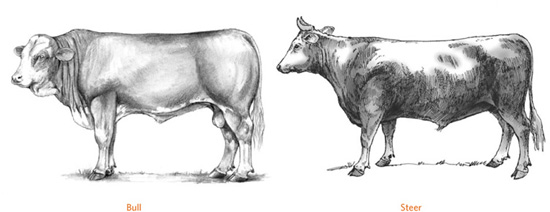

Bull. When a male calf is born, he is considered a bull because he still has male reproductive organs. Most bulls are castrated and become steers. Bulls can be unpredictable and dangerous.

Steer. A bull becomes a steer when he is castrated. The steer may still have a small scrotum or his scrotum may be entirely gone, depending on the castration method used. Beef calves are sold as steers.

Heifer. A heifer is a young female animal. Between her hind legs, she has an udder with four teats on it that will grow as she matures. A bull or steer calf also has small teats, just as a boy has nipples, but they don’t become large.

Cow. Once a female animal becomes older than 2 years of age and has had a calf, she is called a cow. A fresh cow is one that has recently given birth to a calf; a cow freshens once a year.

Your choice in a calf will depend on how much space you have and whether you want to raise a steer to butcher or a heifer that will grow up to be a cow.

Miniature Might

Intimidated by the size of a standard cow? Consider a miniature one. Miniature livestock require less housing space, pasture, fencing, and feed than do their full-size counterparts. You can stock two or three miniature Herefords or Lowline Angus to one garden-variety cow. The three kinds of miniature livestock are naturally diminutive breeds that evolved as small animals to better survive the conditions nature handed them (like Dexters); small breeds that retained their original breed character when their parent breeds were selected for greater size (such as Miniature Jerseys and Lowline Angus); and breeds that were deliberately miniaturized by breeders who selected for smaller stature, often through outcrossing to an established smaller breed (like Miniature Highlands and Miniature Longhorns). One warning about selecting miniatures: Be sure you read up on dwarfism before you buy; dwarfs are not miniatures and should mostly be avoided.

You can be successful with any of the dairy breeds, but you may want to choose one that is popular in your area. The cost will be lower than for a breed that’s less numerous, and when time comes to breed your cow, you’ll have an easier time finding a bull of the same breed, if you so choose.

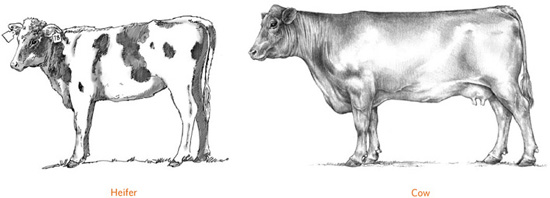

Ayrshire. Originating in Scotland, the Ayrshire is a medium-size red and white cow that may be any shade of red and sometimes dark brown. The spots are usually jagged at the edges. Ayrshires are noted for good udders, long lives, and hardiness. They manage well without pampering and can adapt to rocky land and harsh winters. They give rich, white milk.

Brown Swiss. Coming from the Swiss Alps, the Brown Swiss may be light or dark brown or gray. These cows are noted for their long lives, sturdy ruggedness, and ability to adapt to harsh climates. They give milk with high butterfat and protein content—ideal for cheesemaking.

Guernsey. Originating in the British Isle of Guernsey, Guernsey cattle are fawn and white with yellow skin. The cows are small as cows go, have good dispositions, and have few problems with calving. Their milk is yellow in color and rich in butterfat. Heifers mature early and breed quickly.

Holstein. Coming from northern Germany, Holsteins are large black and white or red and white cattle. A Holstein calf weighs about 90 pounds (41 kg) at birth compared to smaller breeds with calves typically weighing 60 to 70 pounds (27 to 32 kg). The cows are bred to turn grass into large volumes of milk that is low in butterfat. Holsteins are the most numerous dairy breed in the United States.

Jersey. Developed on the British island of Jersey, the Jersey is a small breed that may be fawn colored or cream, mouse gray, brown, or black with or without white markings. The tail, muzzle, and tongue are usually black. Jerseys mature quickly, calve easily, and are noted for their fertility. Jerseys produce more milk per pound of body weight than any other breed, and their milk is the richest in butterfat.

Milking Shorthorn. Originating in Britain, Milking Shorthorns may be red, red and white, white, or roan (a mix of red and white hair). These large cows are hardy and noted for long lives and easy calving. Their milk is richer than that of Holsteins but not as high in butterfat as that of Jerseys or Guernseys.

Buying a mature lactating dairy cow is the easiest way to start with a family milk cow, compared to buying a dairy heifer you must raise for two years, breed, and train before you get your first drop of milk. A mature cow should already be accustomed to being milked, be gentle, and be easy to handle and milk. Check with the person selling her to make sure she’s had the proper vaccinations and they are up to date, and she has been tested for brucellosis and tuberculosis, or any other requirements in your state. When in doubt about the required tests or vaccinations, ask your local veterinarian.

Also find out if the cow has been bred back again for her next calf. Unless she calved within the past few weeks, she should be bred again. You can have her checked by a veterinarian to tell if she is pregnant. If she has been milking for several months and is not pregnant, either the farmer didn’t rebreed her, or the cow has a fertility problem.

A dairy cow should always be rebred about two to three months after she calves, so she will calve again the next year. A cow may go several years without having a calf and still be milked, but her milk production will decline after the first six months and will gradually keep dropping. She will produce more milk for your family if she has a calf every year and is given a chance to go dry (not be milked) for at least 45 days, or better yet 60, before her next calving.

If the cow has recently calved and is not yet rebred, give her two to three months to recover from calving before rebreeding for her next calf. Some cows will come into heat less than a month after calving if they are well fed, but it’s too soon to rebreed them. Just keep track of her heat cycles when she comes back into heat, so she can be bred at the proper time. (For information on detecting heat, see page 302.)

Milk Factory

A top-producing dairy cow gives enough milk in one day to supply an average family for a month. The average milk cow produces 6 gallons a day (23 L), which is 96 glasses of milk. A world-record dairy cow can produce 60,000 pounds (27,216 kg) of milk per year—that’s 120,000 glasses of milk.

Quick Guide to Dairy Cow Breeds

When your cow produces her annual calf, you might sell the calf to help pay for the cow’s maintenance, or you might raise the calf for beef. If the calf is a heifer, you might raise it as a second milk cow or as a replacement for your older cow if she is getting on in age.

A cow’s disposition is created partly by heredity. She inherits from her parents a tendency toward being nervous or placid, flighty or calm, smart or stupid, kind or mean. Just like humans, some cattle are smarter than others, and some are more emotional. But disposition is also influenced by how a cow is handled or trained. With patient handling, a timid, nervous heifer that is smart will often grow up to be a gentle cow. On the other hand, some wild and nervous animals can be frustrating, and dangerous, because they never learn to trust you.

The cow’s attitude will give you clues. She should be mellow and calm rather than nervous and flighty. A milking cow should be accustomed to having people near her and touching her udder. If she is nervous, doesn’t want to stand still, or seems inclined to move away or kick when you touch her udder, she will not make a satisfactory family milk cow.

The word purebred refers to an animal whose ancestors are all of a single breed. A registered purebred has a registration number, recorded in the herd book of its breed association. The association gives the owner a certificate stating that the animal is the offspring of certain registered parents. However, not all purebreds are registered.

If you are thinking of selling your cow’s offspring, you’ll have to decide whether to buy a registered purebred or a grade cow. You are better off buying a good grade cow than a poor registered one. Registration papers won’t guarantee high production or good conformation, and grade cattle can take advantage of the benefits of cross-breeding. So don’t select an animal just because it’s registered.

If you opt for a purebred cow, join the breed association, which can give you educational materials and information and help you market your cow’s offspring. Transfer the registration of your new cow to your name. Be sure the color markings or the ear tattoo on the registration certificate is correct. For the Ayrshire, Guernsey, and Holstein breeds, you may use photos of both sides of your cow or sketches of the markings. For the solid-color breeds such as Jersey and Brown Swiss, an ear tattoo is required.

Performance records and the cow’s pedigree are two other documents you will want if you plan to register and sell your registered cow’s daughters. A pedigree is a record of all the cow’s ancestry. Most successful breeders keep additional detailed records that can be used to compare such factors as birth weight, weaning and yearling weights, milk production, and fertility. If you are not familiar with pedigrees and performance information, have the seller explain the records so you can understand how to use them.

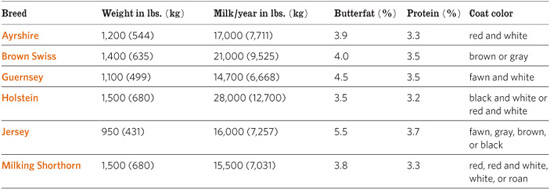

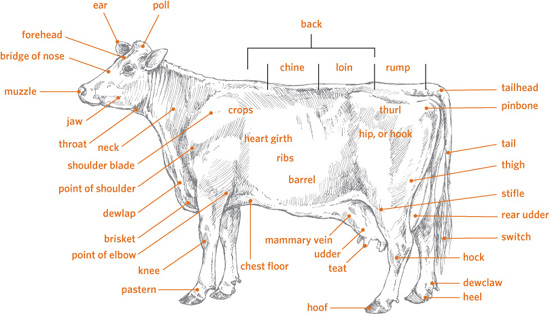

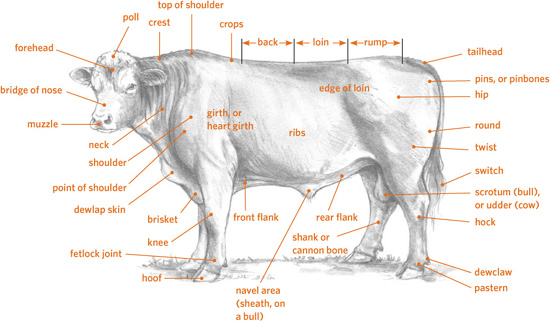

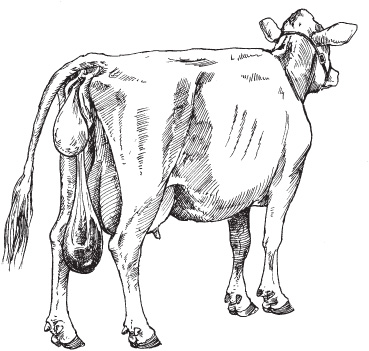

A dairy cow is judged as much by the way she is built as by any other factors. Conformation is as important as performance records. A good milking cow should have outstanding breed character, which means that she closely resembles her ideal breed type. She should have style—all of her parts come together to create a good-looking animal.

Your cow should have good feet and legs. You don’t want a cow that will eventually become crippled because of poorly formed feet and legs. Her hind legs should be straight, not too close together at the hocks or splayfooted, and set squarely under her body. Her front legs should be straight. She should walk freely and smoothly without throwing her feet out to the side or swinging them inward.

The cow must have a feminine head and neck and a long body. A long body gives a cow more room for carrying a calf. She should have a deep, wide rib cage; a long, graceful neck; sharp withers; and a straight back (not humped or swayed) with wide, strong loins. Her rump should be level and square, not tipped up at the rear or slanted downward. If her rump is tipped up and her tailhead is too high, she will have trouble calving. The cow should be well balanced and well proportioned in all of her body parts, not short bodied, shallow bodied, or too short legged.

To give lots of milk, she must have a well-constructed udder. The teats should be evenly spaced, and all the same length and diameter. They should be well shaped and of a size to fit comfortably in your hand—not too long or too fat. Long teats and fat teats are difficult to milk, as are extremely short teats.

The udder should be well balanced, with all four quarters similar in size and shape, well spaced, and level—the front quarters not higher or lower than the rear quarters. The bottom of the udder, between the teats, should be flat rather than bulging. The udder should have strong attachments, meaning the muscles and ligaments holding it up against the cow’s abdomen keep the udder relatively high and tight, rather than hanging low and pendulous. Otherwise the udder may break down as the cow ages, swinging back and forth and hitting her legs as the cow walks or trots, making the udder susceptible to bruising and mastitis. Looking from behind, the udder should appear well attached between the thighs, rather than sagging.

You may be able to buy a cow from a neighbor or a local dairy. You can also check the ads in your local or regional farm newspapers or ask at the farm store—or see if the local veterinarian or county Extension agent knows of anyone with a milk cow for sale. If you pass the word along that you are looking for a family cow, you will eventually find one. It’s always better to buy directly from the previous owner than from an auction. A cow going through an auction is usually being culled for one reason or another. She may be old or crippled, infertile, or have some other problem. Good cows may go through an auction, but you can’t always tell by looking. For instance, a nice young cow may have a uterine infection, making her infertile.

How Long Does a Cow Live?

In an industrialized dairy—where the cows are crowded, pushed for milk production, and stressed out—the average life span is only 4 or 5 years. By the age of 6 a cow is considered old, and few cows are milked beyond the age of 7. A well cared for family cow, on the other hand, may produce milk to 15 years or older, and may survive to the ripe old age of 20 or even 25. The oldest cow on record was an Irish milker named Big Bertha; she died in 1993 just three months short of turning 49.

If you buy from the previous owner, you have more chance to examine the cow closely and ask questions. You can learn more about her history and make sure she’s had all her vaccinations. A dairy might sell you a young, healthy cow that is just not producing enough milk to pay her way. She would be fine, however, for a family milk cow that doesn’t need to be a top producer.

Another place to buy a cow is from a dispersion sale or farm sale, when a dairy is selling out or a farmer is retiring. In such a case you may be able to buy a cow that has just calved, with her new calf at her side.

Beef breeds are stockier and more muscled than dairy breeds. The latter have been selected for their milking ability rather than for beef production, and the cows are finer boned, are more feminine, and have larger udders so they can give much more milk. The many beef breeds have differences in size (height and body weight), muscle traits (lean or fat), color and markings, hair coat and weather tolerance, and so on.

Your best consideration in selecting from among the many breeds is to determine which ones are available locally—since they are more likely to be adapted to your climate, as well as being easier to locate and transport to your place.

You may also want to consider finish size. A small-framed animal takes less feed and usually matures and reaches finish weight more quickly than a large one. If you have a small place or don’t want a huge amount of meat, a small-framed animal like a Dexter or even a crossbred dairy-beef calf from one of the smaller dairy breeds might be just right. If you have a larger acreage and a big family and you want lots of beef, you may prefer to select a calf from one of the larger-framed breeds. A crossbred beef calf is often the best selection, since it will have the advantage of hybrid vigor for better feed efficiency and faster weight gain. Crossbred animals also tend to be hardier and healthier.

Most cattle breeds are horned and some are polled (naturally have no horns). Angus cattle are polled, and some of the horned breeds are infused with Angus genetics so they have black and polled offspring—two traits popular with many stockmen. Now the traditionally red and horned European breeds like Limousin and Simmental have black, polled versions. Angus and Angus-cross cattle have an additional advantage of finishing faster and being ready for butchering in little more than a year, compared to larger-framed breeds that may take two or more years to finish, although the Angus-type cattle will produce less beef.

Dexters are the smallest cattle breed and are used for both milk and beef. The average cow weighs less than 750 pounds (340 kg) and bulls weigh less than 1,000 lbs. (454 kg). Dexter cattle are quiet and easy to handle, and the cows give rich milk.

Beef Breeds

Beef breeds in North America are descendants of cattle imported from the British Isles, European countries, Australia, or India. Many modern breeds are mixes of these imported breeds.

British breeds originated in England, Scotland, and Ireland. They include Angus, Dexter, Galloway, Hereford, Scotch Highland, and Shorthorn.

Continental, or European, breeds are generally larger, leaner, and slower to mature than the British breeds and are popular for crossbreeding with British breeds to add size and muscle (and sometimes milk). These breeds include Braunvich, Charolais, Chianina, Gelbvieh, Limousin, Maine Anjou, Normandy, Pinzgauer, Piedmontese, Romagnola, Salers, Simmental, and Tarentaise.

Some beef cattle breeds originated in places other than the British Isles and Europe. They include the Brahman from India, the Murray Grey from Australia, and the Texas Longhorn, an American breed descended from wild cattle left by early Spanish settlers in the Southwest.

The breed you choose for raising a beef animal for your freezer is not as important as the disposition of the individual you select. Some calves are more placid and easygoing than others. If you are getting only one calf, try to select a mellow one, not a skittish one that will get nervous being by himself. Try to choose a smart and gentle one that will readily learn to trust people.

Don’t choose a wild calf. A wild, snorty calf is a poor risk, even if he is big and beautiful. You may have trouble gentling him, and he may try to go through fences. He could also be dangerous—he might knock you down or kick you. A wild calf won’t gain weight as well as a placid calf. Rate of gain (pounds gained per day) is almost always better with a gentle calf.

An auction is the riskiest place to buy a young calf. Even though the calf may have been healthy when taken to the auction, it may get sick after you take it home. Some calves become sick because they are taken from their mother and sold before they have had a chance to nurse enough colostrum, which is loaded with antibodies that protect the calf against disease until it can develop its own immune system.

The Murray Grey is a silver-gray breed from Australia that is gaining popularity in North America because of its moderate size, gentle disposition, and fast-growing calves. The calves are small at birth but often grow to 700 pounds (318 kg) by weaning.

A sale yard is also a good place to pick up diseases. Cattle come and go, and they spend time in pens before being sold. Some of the cattle brought to a sale may be sick or coming down with an illness. Even if most of the cattle that go through the pens are healthy, germs may contaminate those pens. Don’t buy a calf at an auction if you have other options.

A good place to buy a beef calf is at a feeder calf sale in the fall or at a farm or ranch. A local purebred breeder or commercial cattle producer is always the best source. Buying direct from a local farmer or rancher gives you an opportunity to look at calves, ask questions, and determine the personality and tractability of each animal.

Most dairy farms have many newborn calves to sell in the spring. Dairy cows must have a calf every year to produce their maximum amount of milk. A cow makes much more milk after she freshens. Her volume of milk is greater a month or two after calving. From then on, her production gradually declines. Dairy cows are kept at maximum production by being bred every year to have new calves and then being allowed to dry up briefly before the new calves arrive.

Some dairies sell all their calves. Others keep their heifers and raise them to sell to other dairies. Bull calves are usually sold as soon as they are born and are cheap because most dairy people don’t want to take the time to raise them.

Watch for Signs of Sickness

Before you take home your new cow or calf, make sure it is healthy. The animal should look bright and perky, be lively and energetic, and have a glossy hair coat and a sparkle to the eyes. Bowel movements should be firm but soft, not hard or excessively runny.

If an animal is dull or slow moving, has a dull or rough hair coat, has foul-smelling manure, or has droopy ears, it is sick. Also beware of an animal that stands with its back humped up or has a cough or a runny, snotty nose. If you are in doubt about the health of an animal, have a veterinarian or other person with cattle experience look at it.

After you bring home a calf, pay close attention to detect early signs of illness. Calves easily get pneumonia, and a calf with pneumonia may die. If your calf looks like it doesn’t feel well, don’t wait to see whether it gets better or worse. Get advice immediately from a person experienced at raising cattle, or call a veterinarian.

Some of the calves at a dairy can be crossbred (half beef), if the dairyman breeds his heifers to a beef bull that sires small calves for easy calving. Crossbred calves of either sex can often be purchased cheaply. They make good bucket calves to raise for beef.

The best steer to raise for butcher is a fast-growing, well-muscled animal that will reach a market weight of 1,050 to 1,250 pounds (476 to 567 kg) by the time he is 14 to 20 months of age. Beef cattle are categorized by frame score, which tells you whether they are small, medium, or large bodied. A small-frame, early-maturing steer will not produce as much meat on his small carcass as a larger-frame animal. If you try to get him to grow bigger, he’ll just get too fat; he is not genetically capable of attaining a larger size. A large-frame steer will grow too big before he gets fat enough to butcher and will use up more feed than is necessary. The most practical kind of beef steer has a medium frame.

The animal you pick should have a lot of muscle, not a lot of fat. If the calf is already fat, he may not grow well. On the other hand, the animal should not be too thin, either. Thinness may indicate that the animal has been sick or is currently not healthy. He should have nice, smooth lines and should not be swaybacked. He should have a deep body, neither shallow nor potbellied. He should be long and tall, but not overly tall.

A Steer Is No Bull

If you buy a weaned calf, make sure it has been castrated. You want a steer, not a young bull. Although a dairy calf or a dairy-beef cross is usually cheaper than a beef calf, it most likely will not be weaned. You’ll have the task of feeding the calf milk replacer by bottle or bucket for a few months until it becomes large enough to thrive on pasture alone. Such a calf will likely still be a bull, so you’ll need to castrate it (for details, see page 313). Never try to raise a young bull. Even though he may be friendly and mellow as a baby, he will become more aggressive and unpredictable (and dangerous) as he gets older.

Make arrangements with someone who has a trailer or a pickup truck with a rack to haul your animal home. If you are buying the animal from a farmer, rancher, or dairyman, he may be able to haul it for you; ask what he would charge.

If you will be unloading into a pen or a pasture, a trailer often works best, because it is low to the ground and the calf or cow can step out of it easily. An animal transported on a truck must be unloaded at a loading chute. Even a pickup truck with a rack is often too high for an animal to jump out of without risk of injury, unless the truck can be backed up to a bank or you have a ramp.

Remember that most beef calves have lived with their mothers in large pastures. Some may have seen people close up only during vaccinations or medical treatment, which are scary and painful experiences. Therefore, your calf may be frightened by you, and it may even try to run over you if you get in its way as it comes out of the truck or trailer.

When you get home, make sure the trailer is backed far enough into the pen that the animal has no choice but to enter the pen. The gate of the pen should be swung tight against the trailer. A scared animal may try to bolt through even a small opening. Don’t stand in a place where the animal might run over you. If you are unloading from a pickup truck, make a ramp of sturdy boards.

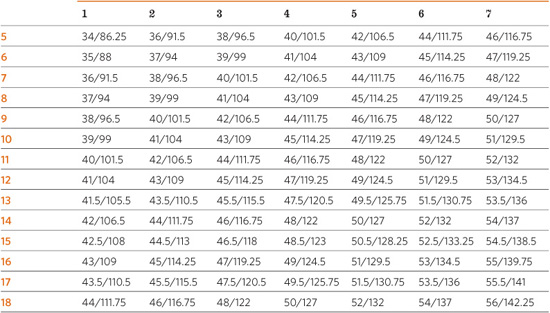

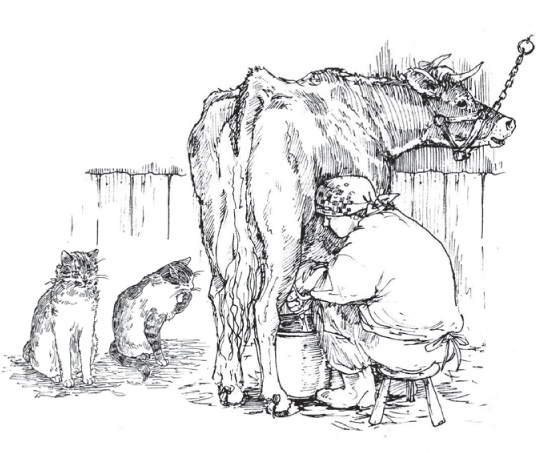

Figuring Frame Score for Beef Calves

To figure a calf’s frame score, measure his height from the ground at the hip when he is standing squarely. Then look up his age on this chart and find the hip height on that age line. Look to the top of the column for the frame score. For instance, a 10-month-old calf that is 45 inches (114 cm) tall at the hips would have a frame score of 4. Calves with frame scores of 1 or 2 are small, 3 to 5 medium, and 6 and 7 large.

Wild cattle were safer in herds. If wolves approached, the cows would bellow and form a tight group. That’s why yearlings and young cattle generally travel in a group. If one goes to water, they all do; if the leader decides it’s time to graze, they all go. They are not just copycats; they hang together for protection.

Your new calf or cow is probably lonely and scared, unless it has another animal for a buddy. Try not to frighten the animal; it may become upset and crash into the fence. To understand your new animal, try to think like it does. Cattle are herd animals and are happiest when they are in a family group with other cattle.

If your calf was weaned before you bought it, it has already gone through the emotional panic of losing its mother. It will miss the other calves it was with, but it won’t be quite so desperate to get out of your pen to find its mother. But if the calf is still going through weaning when you bring it home, it will have several days of stressful adjustment. It may pace the fence and bawl, and it may show little interest in feed or water. A calf being weaned is more susceptible to illness because stress hinders the immune system. In cold, rainy, or windy weather, a weaning calf may be particularly likely to get pneumonia.

As you begin to get acquainted with your new animal, give it time and space. Don’t try to get too close. Until it gets to know you, it may react explosively if it feels cornered.

Speak softly and move slowly around the animal. As you approach the pen with feed, let it know you are there. If its attention is diverted and then it suddenly sees you, it may run off. Talking softly or humming a little tune can help gentle a frightened animal.

Making Friends

Cattle like to be petted and scratched, especially in places that are hard for them to reach. Most love to be scratched under the chin, behind the ears, and at the base of the tail. But don’t rub the top of the head or the front of the face. Rubbing these spots will encourage a cow or a calf to bunt at you.

When you are in the pen with your animal, don’t look directly at it. It will relax more if you act as if you aren’t paying attention to it. If you come too close, approach too quickly, and look directly at it, it will see you as a predator. Instead, ignore the animal, but talk softly as you go by. Pretty soon it will come eagerly to meet you when you bring feed.

Your calf or cow has probably not spent much time with people, so don’t just turn it out and ignore it. Spend some time walking around in the pasture and let it get used to you. Cattle will let you get closer once they know you are nothing to fear.

Some cattle are not timid and will be curious about you from the beginning. Use this curiosity to your advantage. If you are patient and quiet, the cattle will come closer to you.

The flight zone. Cattle have a certain personal space in which they feel secure. As long as you don’t enter that zone, they feel safe. But if you get too close, they’ll get nervous or scared and run off.

Different cattle have different-size zones. A wild or timid calf has a large zone; a gentle or curious animal has a much smaller one. As your cattle get to know you well, the flight zone will disappear.

Use feeding to your advantage. When cows and calves begin to associate you with food, most will lose their fear and come right up to you. They may need a few more days before they will let you touch them, but they will soon stand beside you and eat.

Cattle are good at making associations between things. If you have a special call for feeding time, they’ll come to you every time they hear it.

Don’t spoil your animal. Don’t make the mistake of spoiling a cow or calf. It should trust you, but it must also respect you. Remember that cattle are social animals and accustomed to life in a group, in which they boss other cattle around or get bossed. Cattle will think of you as one of the herd. You must be the dominant herd member; they must accept you as the boss cow. Otherwise, they will try to be too pushy.

If a calf or cow starts pushing you or bunting at you when you are feeding or petting it, discipline it with a swat. Pushing and bunting is the cattle version of play. A calf or cow will naturally want to play fight with you, as cattle do with one another.

If you spoil your animal by letting it do whatever it pleases, you will regret it later. Carry a small stick when you go to feed your animal; if it gets sassy, rap it on the nose. This swat will remind it that you are the boss.

Be careful. Although calves and cows are not likely to attack a person (unless a cow is defending a new calf), they can accidentally hurt you because of their size and weight. Always keep an escape route in mind when trying to corner or work with a cow or a calf. Leave enough room to dodge aside if one backs into you or turns around and runs back out of a corner.

Cattle can be dangerous when handled in a confined area, because they tend to panic. Don’t wave your arms, scream, or use a whip. If an animal won’t move forward into the catch area, prod it with a blunt stick or twist its tail. Just be careful to not twist the tail too hard. You can twist it into a loop or push it up to form a sideways S curve. If you have to twist the animal’s tail to get it to move, stand to one side so it can’t kick you.

Be gentle. If you yell or chase your cattle, you may scare them badly. Even if they are stubborn or suspicious and won’t go into the catch pen or behind the gate or panel on the first try, don’t get impatient. If you lose your temper and yell, you’ll confuse or scare them and make things worse. They’ll be harder to handle next time.

Before you buy a calf or cow, prepare the place where you’ll keep it. A young calf needs shelter from sun, wind, and rain. A mature animal is hardier but still needs protection from driving wind and hot sun. In most climates a three-sided shelter offers sufficient protection from the elements, but if you’ll be milking your cow on cold winter days you’ll appreciate a more secure structure.

If the animal will be living by itself, build a strong pen to put it into for a few days before you turn it out to pasture. Be sure the fence is constructed so the animal cannot jump over or crawl through it. A frantic, homesick animal in a new place may try to escape. If the calf you purchase has already been weaned, it won’t be so desperate to get back to its mother.

Make sure your pen or pasture has no hazards, such as nails or loose wires that might injure the animal. Calves are curious, just like little kids, and they often get into trouble. A pole or board on the ground with nails sticking out of it can cause serious injury if stepped on. Nails or bits of wire lying around near the feeder may puncture the animal’s stomach if it eats them, causing hardware disease, which is often fatal. Don’t leave baling twine hanging on a fence or lying on the ground, and watch for stray garbage: If a calf or cow tries to eat baling twine or chews on a plastic bag that has blown out of your trash, pieces of the material may plug its digestive tract and kill it. Any electrical wires in the barn must be out of your animal’s reach, as well.

The pen must be dry and have good drainage. If necessary, put sand in the bedding area or a shady spot where the animal sleeps to make sure the area stays dry.

Build pens and erect fencing on solid ground. Posts set in a boggy, wet area will become loose and wobbly. The postholes can be dug with a shovel if the ground is mainly dirt with just a few rocks. If the ground is really rocky, you’ll need an iron bar to loosen the rocks as you dig.

Use metal or pressure-treated wood posts to prevent rot. Set the posts in a straight line. A crooked fence is not as strong as a straight one. Set the corner posts and sight between them to line up your postholes and your posts, or stretch a long string between them to give you an exact line. Set holes around the posts with dirt and rocks. To set the posts solidly, put in a little material at a time and tamp the dirt firmly with an iron bar or a tamping stick before adding more. (For more information on putting up fencing, consult a good reference book such as Fences for Pasture and Garden by Gail Damerow.)

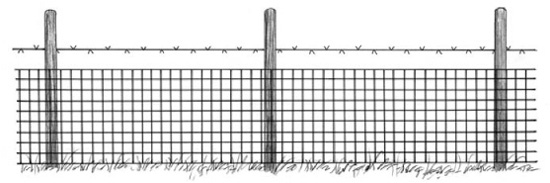

Wire fence. A good wire fence will hold cattle that are not being crowded or trying hard to get out. The wire must be tight, without slack, so the cattle won’t get into the habit of reaching through it. If they can reach through it to eat grass, they may eventually push through it. Net wire is the best option, because cattle cannot get a nose through it.

All calves need shelter, but a brand-new calf is especially fragile and needs to be kept warm and dry. If you live in a cold-weather region, you’ll need to keep a young calf in a warm barn stall or in your garage or back porch until it is several days old and can live outdoors.

A calf pen can be built with sturdy wood posts. The posts should be at least 8 feet (2.5 m) long, enough to set deeply into the ground but make a fence at least 5 feet high (1.5 m), and should be set 8 to 10 feet (2.5 to 3 m) apart. Use poles, boards, wood or metal panels, or strong woven-wire netting as fencing between the posts. Barbed wire or smooth wire won’t work, because a calf can get through it if it tries hard enough. Do not use an electric fence to create the pen. You may need to corner the calf in the pen—or it may corner you—and you don’t want it or you to get shocked. Don’t skimp on materials; a good pen may be expensive to build but will last a long time.

If the calf will spend all of its time in the pen, it should be large enough to give the calf room for exercise, at least 900 to 1,000 square feet (275 to 300 sq m). You can configure the pen however you like, such as 10 by 100 feet (3 by 30 m), 20 by 50 feet (6 by 15 m), or 30 by 30 feet (9 by 9 m)—whatever fits the space you have. If you are raising more than one calf, add at least 200 square feet (60 sq m) of space to the total area for every additional calf. The pen should offer shade from a building or a tree. A calf needs about 100 square feet (30 sq m) of shade in summer.

You’ll need a small catch pen in one corner of your pen and a place where you can restrain the calf for giving shots and medications. A small, enclosed shed or feeding area can be used for cornering and catching the calf. If you make a gated chute at one corner of the pen, you can herd your calf along the fence and into the chute and swing the gate shut behind it. You might include a head catcher or stanchion in the calf’s feeding area, which allows you to lock its head in place when it sticks it through to eat. The stanchion will restrain the calf sufficiently for veterinary care.

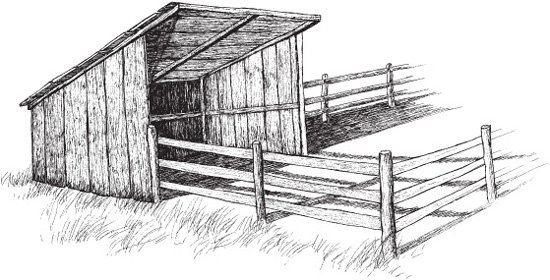

Typical layout for a calf pen and shed

Wire fence with braces and metal stays

Net wire fence with one barbed wire on top

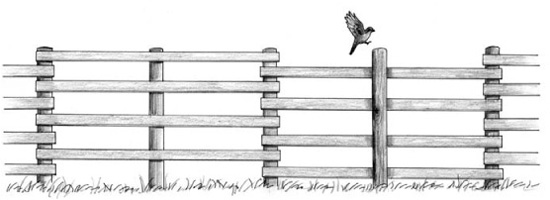

Corral fence with posts and poles

Whenever you inspect your fence, replace any missing staples on wood posts or clips on metal posts so the wire is attached properly. Tighten any sagging wires. Make sure the fence has no holes through which a calf might be able to get out. If the fence stretches over a dry ditch, a calf or yearling may be able to walk right under the fence. Put a pole across the ditch, under the fence, and secure it so that a calf can’t push it away.

Electric fence. An electric fence will prevent animals from getting through or rubbing against a wire fence. After being shocked a few times, the animals won’t touch the fence.

For an electric fence, you’ll need a battery-powered or electric fence charger and insulators to attach the wire to the fence posts. Do not allow the electric wire to touch anything metal; it will short out and won’t work. It also shouldn’t touch wood posts or poles, because it will short out whenever the wood gets wet. Keep all weeds and brush around the electric fence clipped to keep the fence working and to avoid a fire.

A portable or temporary electric fence can be used to divide a large pasture into several smaller ones for pasture rotation. Even if you have only a small acreage, the grass will last longer if you practice rotational grazing

Check That Fence

If you’re raising animals on pasture, you’ll need to check the fences frequently and carefully to ensure they are in good shape. And be sure to give fences a good once-over before you bring home a new animal. A calf or cow that has never lived alone may be frantic when you first bring it home. It may try to get out of the pasture to rejoin the herd it lived with.

In a mild climate, cattle may need only a small three-sided shed, or a protected fence corner with a roof and some boards or plywood on the sides for windbreak. You can make a simple shed by setting a roof on tall, sturdy posts. A freestanding shed with walls on three sides will better protect the animals from bad weather.

Before you build a shed, figure out which way the wind usually blows in that spot. Place the shed walls to offer the greatest protection from wind. Two sheets of exterior-grade plywood placed on each side of a fence corner make a nice windbreak; add another sheet of plywood to make a roof.

If you live in a hot climate, a shed roof will provide shade, but you’ll also need airflow to help keep the animals cool. The roof should be high rather than low, and the shelter should have no walls, which would halt air movement.

The shed should be built on a high, dry spot with good drainage. The roof should slope so rain or melting snow will run off. Make sure it slopes away from the main pen so the runoff doesn’t create mud in the pen or flow into the shed.

Add bedding for your animal to lie in. Straw, bark mulch, or wood chips scattered into a bed in the corner of the shed will give them a dry place to sleep. Make sure the bedding area is in a high, dry spot. The animal should always have dry bedding. Moist, dirty bedding contains harmful bacteria and also conducts warmth away from the animal’s body, causing it to become chilled and more susceptible to disease. Also, ammonia gases given off by bedding that is wet from urine and manure can irritate and weaken the animal’s lungs, especially a young calf’s, and allow bacteria to become established and lead to pneumonia.

A simple shed with two or three walls can provide adequate shelter.

Make a Water Trough

You can make a water trough from anything that will hold water and can be cleaned easily, such as an old washtub or large bucket. You will also need to make a stand or frame to hold the tub. Nail a board across the corner of the pen or stall, leaving room for the tub or bucket to fit snugly between it and the walls. You can easily pull the tub or bucket up out of the corner to rinse and clean it, but cattle can’t tip it over.

In a large pasture, manure serves as fertilizer. But in a pen or shed, it needs to be cleaned out. If an animal spends much time in its shed, manure and soiled bedding must be cleaned out regularly so it doesn’t build up.

A corral may be easiest to clean with a tractor and blade or loader, whereas to clean a shed or bedding area, a wheel-barrow and manure fork will suffice. A manure fork resembles a pitchfork but has more tines, so manure and straw can’t fall through it easily.

Manure makes excellent fertilizer. Spread the manure over your pasture or garden, or make a compost pile from manure and old bedding.

You will need a good halter and rope for restraining your calf or cow so that you can tie the animal to the fence or to the side of the chute if necessary. An inexpensive, adjustable rope halter with lead rope can be purchased at a feed store or through a mail-order catalog from a livestock supply company. When putting on a halter, place it on the animal so the adjustable side is at the left. When you pull it tight, the pressure should be mostly on the rope under the chin, rather than behind the ears.

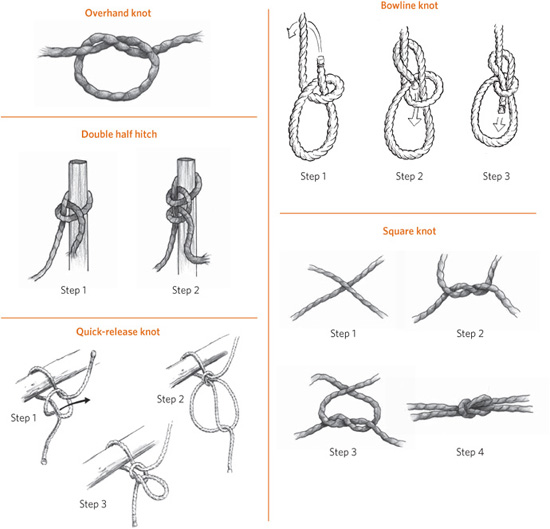

At some point, you may need to tie up your calf or cow. For your safety and that of your animal, you’ll need to know how to make a good knot that will stay tied but can be untied easily, even if the animal has pulled hard on the rope.

Overhand knot. The simple overhand knot is the one you make first when tying your shoes. This basic knot is often the first step in forming more complex knots.

Bowline knot. The bowline knot is probably the most useful nonslip knot for working with livestock. It allows you to tie a rope around the animal’s neck or body without the danger that it might tighten when the rope is pulled, and it is relatively easy to untie. An easy technique for remembering how to tie a bowline knot is to think of the following story. The first loop is the rabbit hole, the standing part of the rope is the tree, and the working end of the rope is the rabbit. The rabbit comes out of the hole, runs around the tree, and goes back down its hole.

Double half hitch. The double half hitch knot is quick and easy to tie, acts like a slipknot, and is a handy way to secure the rope around an animal’s leg when you are tying a leg back or to secure the end of the rope when no other knot seems appropriate.

Square knot. The square knot is a stronger version of the overhand knot; it consists of two overhand knots, one tied on top of the other. The square knot is perfect for joining two pieces of rope, as when you are joining a broken rope or tying a rope around a gate and gatepost to keep the gate closed. A properly tied square knot will not slip from its position.

Quick-release knot. The quick-release knot (also called a reefer’s knot, a bowknot, or a manger tie) is useful for tying your calf to a fence post. Like the square knot, it is a good nonslip knot. The quick-release knot has the advantage of being easily untied even after it has been pulled tight, as will happen if your calf pulls back on the rope.

Common Knots

To tie the five most common knots, follow these simple step-by-step diagrams.

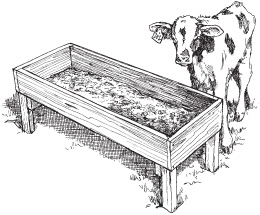

Cattle require a source of fresh water, which can consist of a tub or tank filled twice a day with a garden hose. A water tub for calves should be set up off the ground, but no higher than 20 inches (50 cm); anything higher will keep them from drinking easily. Calves may step or poop in a tub on the ground. Using a feed rack or manger will reduce hay wastage. Cattle won’t eat hay that has been stepped on or has manure on it.

You must make sure your cattle have water available at all times. Cattle drink more in hot weather than in cold weather, so check the trough more often in summer. In the winter, keep the water from freezing, even if it means breaking ice every morning and evening. In really cold climates, a rubber tub is a useful water tub, because you can tip it over and pound on it to get the ice out without creating a leak. If you use a hose to fill the trough, drain the hose thoroughly after each use in cold weather to keep it from freezing.

The water should be kept away from the feed rack or feeding area to keep cattle from dragging feed into the water. It should be located far from where the cattle bed. If the cattle have to walk some distance to the water, they will be less likely to stand close to it and defecate in it by accident. Keep the water fresh and clean, even if you have to dump and rinse the tub every day; cattle won’t drink dirty water. Use a tub or tank that is easy to dump or has a drain hole at the bottom, and rinse it before refilling. The more cattle you have, the larger the tank you will need, or the more often you’ll have to fill it.

Clean out any hay that collects in the bottom or corners of the feeder; wet hay may become moldy. Moldy feed may make your animal sick, and the mold spores that are released into the air when the animal eats may make it cough. To help prevent dampened hay, place the feed area inside a weather-resistant shed. If you feed your cattle outdoors, build a roof over the feed manger, hayrack, or grain box or tub.

If you are feeding hay in winter or when pasture gets short, scatter the hay on well-sodded ground. More hay will be wasted if cattle are fed on bare dirt or mud.

Some people like to fatten their beef cattle on grass, without any grain, though grass feeding takes longer to get a calf up to butchering weight. If you prefer grainfed beef, you’ll have to feed your calf grain every day after it is weaned.

You’ll need a sturdy trough or grain box, mounted off the ground so the calf won’t step in it and held securely so the calf can’t pull it down. Calves will not eat dirty grain. A rubber tub is easy to wash out and works well if you have only one calf. Build a roof over the tub or feed box to keep the grain dry.

Clean out any leftover kernels before adding new grain to the box. If birds have pooped in the tub or trough, or any old, fermented, or moldy grain remains in the corners, the calf may refuse to eat the next batch you put in.

A salt box or grain box can be made of four 1 in. by 8 in. (2.5 × 20 cm) boards and a bottom.

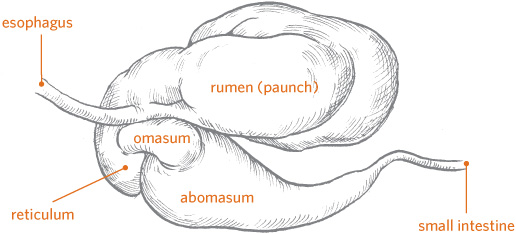

Cattle are ruminants, meaning they have four stomach compartments and chew their cud. The four compartments of a ruminant’s stomach are the rumen, the reticulum, the omasum, and the abomasum or true stomach, which is similar to the human stomach.

When a ruminant eats, it chews food only enough to moisten it for swallowing. After being swallowed, the food goes into the rumen to be softened by digestive juices. After the animal has eaten its fill, it finds a quiet place to chew its cud. It burps up a mass of food along with some liquid, swallows the liquid part, and then chews the mass thoroughly before swallowing it and burping up some more. The rechewed food goes into the omasum, where the liquid is squeezed out, and then goes on into the abomasum. Ruminants developed this way of eating so that they could cram in a lot of feed while grazing in open meadows and then retreat to a safe, secluded place to chew more thoroughly.

Make a Feed Trough

You can make an inexpensive feed trough with 2-inch (5 cm) lumber cut into lengths. If several calves will be using the trough, allow 3 square feet (1 sq m) per calf. Make the sides of the trough at least 6 inches (15 cm) high. Set the trough no higher than 18 to 20 inches (46 to 50 cm) off the ground.

Cattle do well on a wide variety of feeds. To some extent, what you feed your animal depends on whether it is being raised for beef or milk. However, the basic elements of good nutrition are the same for all cattle. Make sure the feeds contain a balance of the basic ingredients for good nutrition: protein, carbohydrates, fats, vitamins, and minerals.

Protein. Protein is necessary for growth. Good sources of protein include high-quality legume hay, such as alfalfa or clover; pasture grasses; or high-quality grass hay. (With alfalfa, care must be taken to avoid bloat—see page 316.) Protein supplements include cottonseed meal, soybean meal, and linseed meal. Cattle that are feeding on good hay or pasture don’t need supplements.

Carbohydrates and fats. Carbohydrates and fats provide energy and are used for body maintenance and weight gain. Barley, wheat, corn, milo (grain sorghum), oats, and grain by-products, such as mill run and molasses, contain a high proportion of carbohydrates and a small amount of fat. Extra fat can be fed using a high-fat product designed for ruminants, such as Calf Manna.

Vitamins. Vitamins are necessary for health and growth. Green pasture, alfalfa hay, and good grass hay contain carotene, which the animal’s body converts into vitamin A. Overly mature, dry hay may be deficient in carotene. The other vitamins cattle need are either in the feed or created in the animal’s gut, except for vitamin D, which the animal’s body synthesizes from sunshine. Your cattle will get enough vitamin D unless they spend all their time indoors.

Minerals. Minerals occur naturally in roughages and grain. Cattle don’t normally need mineral supplements beyond those found in ordinary feeds. However, if the soil in which their feed was grown is deficient in iodine or selenium, they may require supplements of these minerals. In some regions and situations, they may also need copper supplementation, phosphorus, or some other mineral to prevent deficiency. Check with your local Extension agent or cattle nutritionist for advice on the mineral needs of cattle in your area and always inquire before adding supplements. Some supplements are harmful if overfed.

Cold-Weather Feeding

In cold weather, cattle need more feed to generate body heat and keep warm. Roughages provide more heat than do grains, because of the fermentation that takes place during digestion. If the weather is cold, increase the ration of grass hay.

Salt is important for proper body functions and for stimulating the appetite. It is the only mineral not found in grass or hay. Always provide salt for your cattle, either in a block or as loose salt in a salt box. Trace mineral salt can be used if feeds in your geographic region are deficient in certain minerals. Trace minerals include cobalt, copper, iodine, iron, manganese, selenium, and zinc. Your veterinarian or county Extension agent can help you figure out which kind of salt to use and whether it should include trace minerals.

If your cow or calf is grazing on lush spring pasture, you may need to feed extra magnesium to avoid grass tetany, which can be fatal. Check with your vet, Extension agent, or local feed store.

Grain enables a beef calf to reach market weight faster, and a cow needs grain to meet her nutritional needs while producing milk as well. Grains, also called concentrates, include corn, milo, oats, barley, and wheat. In the Pacific Northwest barley is plentiful and can be used instead of milo or corn.

Cattle and other ruminants have four-part stomachs.

Cattle need about 3 pounds (1.5 kg) of hay daily for each 100 pounds (45 kg) of body weight. For example, a 500-pound (227 kg) calf needs about 15 pounds (7 kg) of good hay each day. If you wish, you can reduce the hay ration by replacing some of the hay with grain. Since grain is a more concentrated source of nutrients, substitute about a half pound (225 g) of grain per pound of hay. Overfeeding on grain can cause digestive problems or founder, so grain should never constitute more than half the ration by weight.

Wheat is usually too expensive to feed to cattle. Corn is high in energy and is commonly used for calf feed when it is available. Oats also make good feed, as does dried beet pulp with molasses.

Roughages, sometimes called forages, are feeds that are high in fiber but low in energy—such as hay or pasture—and are the most natural feeds for cattle. Although cattle do well on them, they don’t grow or fatten as fast as they do on grain. If you are raising a beef animal and don’t need it to grow quickly, or you are raising a weaned heifer to keep as a cow, feed mostly roughages and little or no grain.

If you don’t have pasture for your cattle, you’ll have to feed them hay, which is basically pasture plants that have been harvested and dried. The type of hay you feed will depend on what’s available in your area. Alfalfa, clover, and timothy are common, but any number of other grass and legume hays are suitable.

Alfalfa hay is richer in vitamin A, vitamin E, protein, and calcium than grass hay, but be careful not to overfeed your cattle on it. Alfalfa hay can cause digestive problems and bloat, meaning the rumen becomes too full of gas. The gas causes the rumen to expand like a balloon and puts pressure on the animal’s lungs and large internal blood vessels, causing it to die. Feeding a mix of grass hay and alfalfa hay is safer.

First-cutting alfalfa often has a little grass in it and can be an ideal hay. Second- or third-cutting alfalfa is generally richer and more likely to cause bloat. In addition, alfalfa hay becomes moldy more readily than grass hay if it gets wet or is baled when it is too green. When buying alfalfa, make sure it is green and bright, with lots of leaves and fine stems; it should not be coarse or brown and dry. Alfalfa that is cut early, before it blooms, is finer and more nutritious. Alfalfa that has bloomed has less protein and coarse fiber with larger stems.

Make sure any hay you buy is not moldy or dusty, because mold and dust may create digestive or respiratory problems. Hay for calves should not be stemmy or coarse. Because the protein and nutrition of hay are mainly in the leaves, stemmy hay is not nutritious, and it’s hard for a calf to chew. Adult cattle can handle coarser feed than calves can. If you have no experience in buying hay, ask your county Extension agent or another knowledgeable person to help you.

Pasture should contain several types of nutritious grasses. Cattle won’t do well in a weed patch. If you are a pasture novice, have your county Extension agent look at your pasture and offer advice on any needed renovation.

In the early spring, pen up your cattle and feed them hay for a while to let the pasture grow. Otherwise, your cattle will eat the new green grass as soon as it starts to grow, and it won’t become tall enough to provide sufficient feed for the summer. Some pasture plants become coarse as they mature, and your cattle will not eat them. Weedy areas may also be a problem. You can improve the pasture by mowing or clipping weeds so they don’t go to seed and spread. If the pasture has bare spots, you can seed them by hand scattering a pasture mix when the ground is wet.

If you live in a rainy area, your pasture will grow just fine without much help. But in a dry climate, pasture must be watered with a ditch or sprinklers so it won’t dry out by late summer.

Lush green grass has as much protein and vitamin A as good alfalfa hay. For a growing calf or a milking cow, good pasture is hard to beat, but keep a close watch on your grass. Dry pasture is poor feed, because it loses its nutrients. If the grass gets short or dry, feed your cattle some good hay to supplement the pasture.

Pasture Rotation

When cattle stay in the same area all the time, they overgraze short, tender grasses and ignore the mature, coarse grass unless nothing else is available to eat. The grasses and plants in a pasture become less healthy if they are overgrazed or undergrazed. To avoid this problem, confine cattle to one segment of pasture where the grass is at least 4 inches (10 cm) tall and move them to another segment before they graze the first one too close to the ground. The first section will have regrown by the time the cattle get back to it. By dividing your pasture into two or three portions and grazing your cattle on them sequentially, you can improve your overall pasture condition, increase forage production, and extend the grazing season to save money on purchased hay.

Whether you purchase a newborn calf from a dairy or the calf is born on your farm, you’ll be responsible for feeding it. (If it is born on your farm, you’ll be milking its mother.) For the first few days of a calf’s life, split the daily feeding into three parts and feed every 8 hours. You can feed the calf early in the morning when you get up, again in the middle of the day, and at night just before you go to bed. Once the calf is 1 week old, you can begin feeding twice a day (every 12 hours, morning and evening), which makes life a bit easier.

Your calf should have adequate colostrum. When buying a calf from a dairy, the calf may have been allowed to stay with its mother until it has nursed once or twice. Some dairymen prefer to take the calf away before it has nursed, put it into a clean pen, and feed it from a bottle. The colostrum from the cow is milked out and saved to feed to calves.

When taking a newborn calf home from a dairy, ask to buy a gallon (4 L) or two of fresh colostrum to take with you. Store the colostrum in scrupulously clean containers in your refrigerator, and feed it as long as it lasts. If the calf was born to your milk cow, it will get plenty of colostrum by nursing naturally. (See page 310 for information on making sure the calf nurses.)

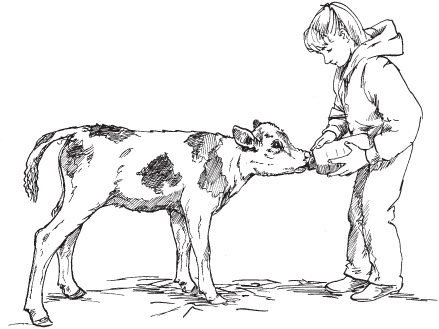

Teaching a calf to drink from a bottle is easier if she has never nursed from her mother. A hungry newborn calf will eagerly suck a bottle for her first meal. But the calf that has already nursed from her mother is spoiled, preferring the taste and feel of the udder. These calves can be stubborn and require patience to get them to nurse from a bottle.

If the calf was with its mother awhile, it knows how to nurse from a cow but not from a bottle. You’ll need to quickly teach it to nurse from a bottle—you don’t want it to go hungry for very long. A young calf needs to eat several times a day.

Don’t Overheat Milk

Never overheat milk or milk replacer. Overheating damages the proteins.

If a calf’s first few feedings with a bottle are colostrum instead of milk replacer, it will more willingly suck the bottle. Colostrum not only tastes better but is also the best food for a calf at this time.

The keys to teaching a stubborn calf to suck a bottle are persistence and the use of real milk (preferably colostrum). The milk should be warm; young calves hate cold milk. Heat the milk so it feels pleasantly warm on your skin but not hot. If it is too hot, it will burn the calf’s tender mouth and the calf won’t suck.

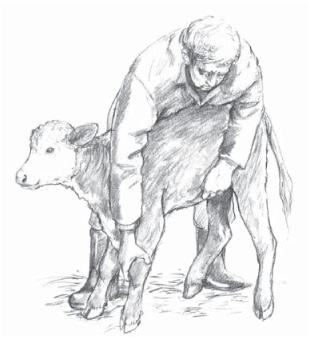

To feed the calf, back it into a corner so it can’t get away from you or wiggle around too much. Straddle its neck and use your legs to hold it still, leaving both hands free to handle its head and the bottle.

Use a nipple that flows freely when the calf is sucking, so it won’t get discouraged by having to work too hard. However, the milk shouldn’t flow so fast it chokes the calf. Hold the bottle so the milk will flow to the nipple. The calf shouldn’t be sucking air. Don’t let it pull the nipple off the bottle.

A newborn calf is more easily fed from a bottle if it has never nursed from its mother.

If you have no cow to provide milk for your calf, or you wish to use your cow’s milk for other purposes, milk replacer is available as a nutritional substitute for feeding young calves. A calf accepts milk replacer more readily when it is introduced gradually.

If you got some colostrum for your young calf, divide it into several feedings to get through the first day or two while you are teaching the calf to nurse from a bottle. If you cannot obtain colostrum, use whole milk, preferably raw milk from a dairy rather than pasteurized milk from a store. The calf will like the taste of raw whole milk better than that of milk replacer.

Before you run out of colostrum or milk, start mixing it with milk replacer to gradually adjust the calf to the taste of what she’ll drink from then on. If you switch suddenly to milk replacer, she may dislike the taste of the new stuff and be stubborn about accepting it.

You can buy milk replacer at a feed store. Of the many kinds and brands, some are better than others. Ask a dairy-man or your county Extension agent to recommend a good brand, and read the label to find out what the milk replacer contains.

Protein and fat content. The National Research Council recommends using a milk replacer with a minimum of 22 percent protein and 10 percent fat. But calves will do better if the milk replacer contains 15 to 20 percent fat; they will grow faster and be less apt to get scours from inadequate nutrition.

Fiber content. Check the fiber level in your milk replacer. Low fiber content (0.5 percent or less) is ideal because it means the replacer has more high-quality milk products and less filler.

Calf Feeding Program

Protein sources. Check the protein sources in a milk replacer. Are they milk-based or vegetable proteins? Milk protein is the highest quality and best for the calf, because the newborn calf has a simple stomach. Her rumen, for digesting roughages and fiber, is not working yet. She can digest and use protein from milk or milk by-products more easily and efficiently than she can use protein from plants.

Mixing milk replacer. Follow the directions on the bag. The powder is mixed with warm water and fed like milk. The recommended amount varies by brand.

The powder mixes better if you put the warm water into your container first and then add the replacer to the water and stir until it is all dissolved. It won’t mix quickly if the water is cool or lukewarm. Start with water that is a little hotter than you want it to be when you feed the calf; the temperature will be just right by the time you mix in the powder and take it out to feed the calf.

Storing milk replacer. Keep milk replacer powder dry and clean. It will spoil if it gets damp. Close the bag immediately after measuring out the correct amount. Keep it in a container with a tight cover. The quality may be reduced and the replacer may become contaminated with germs if the bag is left open and exposed to light, moisture, flies, and mice.

It’s just as bad to overfeed a calf as to underfeed. Too much milk can upset digestion and cause diarrhea. Feed your calf according to its size: A big calf needs more milk than a little one. Weigh or measure the milk to make sure you are not overfeeding the calf.

Feed 1 pound or about 1 pint (453 g or about 475 mL) of milk daily for each 10 pounds (4.5 kg) of body weight. Thus, a calf that weighs 90 pounds (41 kg) should get 9 pints (4.25 L) daily—4½ pints (just over 2 quarts)—in the morning and again in the evening, or about a gallon (3.75 L) a day.

Feed at the same time each day on a regular schedule so as to not upset the calf’s digestive system. If the calf gets diarrhea from being overfed, immediately halve the amount of milk for the next feeding. Then gradually increase it to the recommended amount for the calf’s size. As it grows, you can increase the amount of milk, but don’t feed more than 12 pounds (5.5 kg), or 1½ gallons (5.5 L), of milk daily.

Keep Feeding Equipment Clean

Always carefully wash your bottle or nipple bucket after each feeding; otherwise, bacteria will grow on it and may make the calf sick. Nipple buckets must be taken apart and cleaned. Use a bottle brush to thoroughly clean bottles.

If you are feeding more than one calf, a nipple bucket can save you time. Once a calf learns how to suck a bottle, you can switch it to a nipple bucket. You don’t have to hold the nipple bucket while the calf nurses. The bucket can be hung from a fence or a stall wall. Hang it a little higher than the calf’s head, where the calf can reach it easily.

Don’t enlarge the nipple hole on a nipple bucket. Some people widen it so the milk flows faster, decreasing the time the calf takes to drink the milk. But if the milk runs too fast, the calf may inhale some of it because it can’t swallow the milk fast enough. Milk in the lungs can lead to aspiration pneumonia, which can’t be cured with antibiotics and will kill the calf.

You can teach your calf to drink from a pail instead of a nipple bucket. Put fresh warm milk into a clean pail and back the calf into a corner. Straddle its neck and put two fingers into its mouth. While it is sucking your fingers, gently push its head down so its mouth goes into the milk. Spread your fingers so milk goes into the calf’s mouth as it sucks. After several swallows, remove your fingers. Repeat this procedure until the calf figures out that it can suck up the milk. A pail is easier to wash than a nipple bucket or a bottle.

Feeding from a nipple bucket saves time, because you don’t have to hold it while the calf drinks.

A calf needs help to learn to drink from a pail.

Get your calf to eat dry feed—hay and concentrates—as soon as possible. At first the calf won’t consume much dry feed, but it should learn how to eat it.

Hay. A growing calf needs roughages for fiber. A calf uses the bulkiness of roughage—hay, grass, corn silage, straw, and cornstalks—to develop its digestive system so its rumen can begin to function properly. A baby calf that can follow its mother’s example begins eating hay or grass at just a few days of age. But when a calf doesn’t have its mother to show it how to eat, you have to encourage it to eat hay. Put a little leafy alfalfa hay into its mouth after every milk feeding, until it learns to like it.

Give your calf hay as soon as it will start nibbling on it. Calves have small mouths and cannot handle coarse hay, but they will nibble on tender leafy hay. Fine alfalfa, clover, or grass hays—or a mix of these—are all nutritious. Give the calf just a little bit of fresh hay once or twice a day. Don’t give your calf much hay at one time, because the hay will be wasted; baby calves won’t eat hay that has been tromped or lain on.

Good green pasture is excellent feed for a calf, as long as it is getting some milk (or milk substitute) and grain. If the pasture is not top quality and lush, the calf may also need a little alfalfa hay, which has more protein and other necessary nutrients for the growing calf than mature or dried-out pasture. A calf that is penned without access to pasture definitely needs alfalfa hay as its roughage source.

Concentrates. A growing calf needs concentrates for energy. Concentrates are feeds that are high in nutrients relative to their bulk, and can be in the form of grains, starter pellets containing grains plus milk products, or a complete starter containing not only grains and milk products but also some roughage. Teach your calf to eat concentrates as soon as possible. Put some into its mouth after each feeding of milk until it learns to like it. You can then feed it in a tub or feed box.

Starter pellets have a high protein level, as well as providing the energy a calf needs for growing. The starter can be offered as early as the first week of life. A calf that will eat enough high-quality dry starter ration won’t need milk and can be weaned young. Early weaning can reduce costs if you are buying milk replacer. You can feed the calf alfalfa hay and starter pellets until the calf no longer needs the milk products. At that point you can transition the calf to grain and good hay or pasture.

Grains should be offered to the calf by the time it is 3 weeks of age. At first, about 1 cup or ¼ pound (236 mL or 125 g) of grain is all a young calf can eat each day. Increase the amount gradually until the calf is eating about 2 pounds (1 kg) of grain daily by the time it is 3 months old. Never wean a calf until it is eating about 2 pounds (1 kg) per day. After the calf has been weaned, continue feeding all the grain starter it will finish daily. By the time it is 3 to 4 months old, it may eat as much as 4 to 5 pounds (2 to 2.5 kg) of grain daily. A calf being fed a grain starter also should be given hay, and should be eating hay well for at least 1 week before weaning.

Complete starter works well if you don’t have a source of good-quality roughage for the calf; if you have alfalfa hay, you don’t need the complete starter. If you do use a complete starter, feed it free choice, meaning leave it available at all times and let the calf eat as much as it wants. Since complete starter includes roughage, the calf won’t need hay until it is about 3 months old. Before you discontinue the complete starter, give the calf some hay for at least two weeks, and make sure your calf is eating the hay well.

The Importance of Water

Make sure your calf has fresh, clean water every day and access to trace mineral salt. Calves need water, even though they get fluid with their milk or milk replacer. Water is especially important in hot weather.

Grain starter or a complete starter can be fed to a calf until it is 4 months of age to help it through the weaning process. A calf should eat at least 1 pound (500 g) of starter daily for every 100 pounds (45 kg) of body weight before it is weaned. Use a weight tape to estimate your calf’s weight.

The age at which you wean your calf will depend on several things, including feed sources, the calf’s health, and how long it has been eating solid food. A calf can be weaned from milk when it is as young as 8 weeks, but most calves are weaned at the age of 3 months. A calf weaned before it is eating enough grain and hay won’t do well. It’s better for such a calf to stay on the nursing program longer.

Weaning is easier if the process is gradual. Start by decreasing the amount in its twice-daily bottle or bucket feedings. Cut back to about three-quarters of the amount you’ve been giving. Feed this reduced amount for a few days, and encourage the calf to eat more grain, feeding it right after it finishes its bottle or bucket. The calf will then be interested in the grain and not as upset with you for shortchanging on milk. Then go to one feeding of milk a day, giving grain at the other feeding time. Then stop the milk feedings. Give grain at the time of day when you used to offer the milk.

The rumen takes a while to enlarge so the calf can eat enough solid food to give it the nutrition it needs. Right after weaning, a calf still doesn’t have much rumen capacity. It may eat just a small amount of hay compared with the amount of grain it can handle. The amount of hay consumed will increase as the rumen develops further.

Don’t Wean Too Soon

It doesn’t hurt to keep a calf on milk or milk replacer for quite a while, but it does hurt to wean a calf too soon. Use your best judgment to decide when you think your calf is ready to be weaned.

After your calf is 3 months old and weaned, gradually change from feeding starter to a growing ration. A growing ration should contain at least 15 to 18 percent protein. If you have good pasture or alfalfa hay, the necessary protein can be supplied by supplementing pasture or hay with 4 to 5 pounds (2 to 2.5 kg) of daily grain.

Keep some hay in front of your calf all the time in a place it can easily reach. The hay should be fine stemmed and leafy, with no mold or dust. As the calf grows, hay can become a larger part of its diet. After it is 5 or 6 months old, good pasture can be used in place of hay.

A beef calf purchased from a cattle farmer will already have been weaned by its mother and will be accustomed to eating solid feed by the time you acquire it. When you bring the calf home, have feed and water in the pen.

Leave some good hay where the animal can find it easily, but not in a corner or along the fence line where the calf will walk on it every time it goes around the corral looking for a way out. Use really good grass hay or a mix of grass and alfalfa. Don’t give rich alfalfa hay to a newly acquired calf; it may make the animal sick or bloated. You can gradually adjust it to good alfalfa hay later.

Give it all the hay it will eat. Then slowly start it on grain, if you wish. Give the calf just a little bit until it learns to eat the grain, and then increase the amount gradually. Too much grain all at once may upset the calf’s digestion.

Give water in a water trough or in a bucket that is hooked to the fence or the stall wall so it can’t tip over. If the animal has never drunk from a bucket, you may have to put the bucket next to the feed, or feed the animal next to the water trough for the first day or two, so it will find the water when it comes to eat the hay.

Grassfed versus Grainfed

A weaned beef calf can be raised on roughages alone but will grow faster and get fatter sooner if you feed it grain. Some people prefer the flavor of grassfed beef and feel grainfed beef has too much fat. Others find grainfed beef to be more tender and juicy compared to grassfed beef. The eating quality of beef depends on many things besides taste preferences in beef, including the quality of forage during the finishing phase of grassfed beef and the age of the animal at finishing. Other factors include the animal’s age, length of time on grain or on high-quality forage, genetic differences in marbling ability, and whether or not the animal was gaining weight at the time of slaughter. An animal that is just maintaining weight or is losing weight, as well as an older animal past the age of 3 or 4, will generally be less tender.

Expected Finish Weight for a Beef Steer (in lbs./kg)

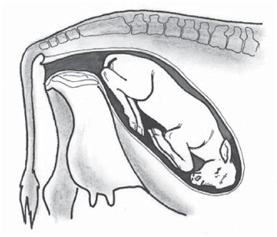

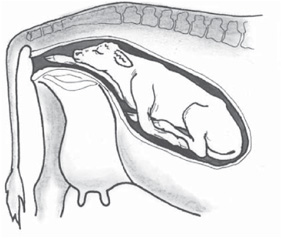

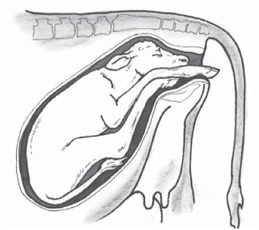

If your calf is a cross of two of these breeds, look at the figure where their charts meet. For instance, the top line shows the weights of Angus and Angus crosses. Heifers of the same breeds and crossbreds weigh about 80 percent of these values.