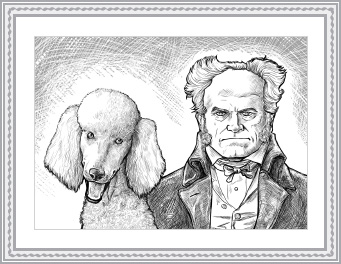

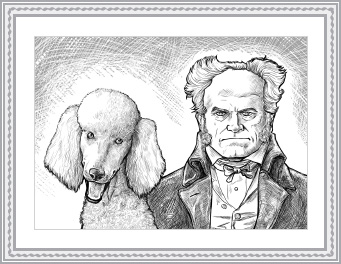

THE FAMOUSLY MISANTHROPIC German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer spent twenty-seven years of his life living alone, averse to human company, but like other notorious malcontents, he was deeply attached to his dogs. Throughout his life, from his student days at Göttingen until his death at Frankfurt am Main, Schopenhauer owned a succession of standard poodles—a famously loyal, active, and intelligent breed. “To anyone who needs lively entertainment for the purpose of banishing the dreariness of solitude,” he wrote in 1851, “I recommend a dog, in whose moral and intellectual qualities he will almost always experience delight and satisfaction.”

Though he remained loyal to the standard poodle, the philosopher’s companions varied in color. The dog he owned in the 1840s was white, and the one he owned at his death—and for which he provided generously in his will—was brown. According to the few guests who visited his home, Schopenhauer was deeply attentive to these animals; though his daily routine was rigid, he always made sure his poodles got regular constitutionals. He even concerned himself with their daily amusements. One colleague recalled being in the middle of an earnest conversation with the philosopher at his home when they were interrupted by the music of a regimental band passing the window, at which point Schopenhauer got up and moved his poodle’s seat closer, to give him a better view of the procession.

The philosopher was ahead of his time in his concern for animal suffering. “When I see how man misuses the dog, his best friend; how he ties up this intelligent animal with a chain,” he wrote, “I feel the deepest sympathy with the brute and burning indignation against its master.” Yet curiously, while he respected his dogs as individuals, Schopenhauer gave every one of them the same name: Atma (though his last dog—the brown one—generally went by the nickname “Butz”). Atma is the Hindu word for the universal soul (or, as Schopenhauer interpreted it, the impersonal, primordial, eternally renewed force of nature). Historians of philosophy have suggested this naming habit may be connected to Schopenhauer’s theory of individuality, and his notion that a particular type of animal expresses the Platonic ideal of its kind.

It may, on the other hand, have been something more familiar: an attempt to forestall the pain of loss. This is why the authors Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas gave their new dog—also, coincidentally, a standard poodle—the same name as the dog they’d just lost: Basket. The first Basket was an elegant creature acquired by Toklas at a Parisian dog show, and so named because she immediately pictured him carrying a basket of flowers in his mouth (a skill he never fully mastered). The poodle was treated like a young prince, bathed daily in sulfur water for the benefit of his sensitive skin. Stein let him sit in her lap when she wrote (“on Mount Gertrude,” said Alice), and she claimed the rhythm of the dog’s breathing taught her the essential difference between sentences and paragraphs. When Basket died in 1937, the bereaved women, on the advice of a friend, acquired a similar-looking dog, and gave him the same name.

When the second Basket arrived in 1938, the couple were living in France. Despite widespread rationing, Basket II didn’t go hungry. The Nazis’ theory of racial purity extended even to pets; as long as a dog had a documented pedigree, it received a food allowance. Basket II lived fourteen years, six past the death of Stein herself, and when he died, Alice B. Toklas was left alone. “His going has stunned me,” she wrote to her friend Carl Van Vechten. “For some time I have realized how much I depended upon him and so it is the beginning of living for the rest of my days without anyone who is dependent on me for anything.” She was too old, she reasoned, to acquire a Basket III.

It’s natural that a bereaved pet owner should want to stave off the pain of loss by acquiring a second dog that resembles the original, and while I can understand the impulse to name a new dog after a beloved old one, the scheme has a major flaw. In my experience, whatever their breed, dogs are unique and as individual as humans, and you can’t make a gentle dog tough just by calling him Butch. Ideally, we should wait until we’ve gotten a sense of a dog’s personality before picking out a name, but puppy owners, like would-be parents, usually have a name in mind long before they lay eyes on their new arrival.

Grisby is the first and only dog I’ve ever owned, and I had his name picked out before he was even born. One evening, my partner, David, and I watched a French movie from 1954 called Touchez Pas au Grisbi (translation: Don’t Touch the Loot). The film is about a band of world-weary French gangsters who sit around in a bar planning a heist and mumbling about le grisbi (old-fashioned French criminal slang whose equivalent is something like “loot” or “booty”). As I recall, we both thought the word would be an appropriate name for the dog we were planning to acquire, not only because it is French (though we’ve Anglicized the spelling) but also because it’s a tough, macho way of saying “treasure,” perfect for a little French bulldog.

The first time I ever laid eyes on one of these creatures, I was walking through Greenwich Village, which of all areas in the United States contains perhaps the greatest concentration of the breed. I was immediately intrigued and enchanted by this odd little animal, with its flat snout and prominent ears. I wanted one so badly it hurt, though it would be another six years before I could fit a dog into my life. Then, when the time was right, I logged on to PuppyFind.com, and there was “Oliver”—a tiny dog with enormous ears and an endearingly inquisitive expression. He was, I thought, the sweetest-looking puppy I’d ever seen, and he’d be weaned by the middle of August, which was exactly when we’d be ready for him. I e-mailed David the photo, though it was a symbolic gesture only—I already knew he was the one. By the end of the day, our deposit to the breeders had been paid, and “Oliver”—all ears—was all ours.

As of the time of writing, Grisby is almost eight years old, and he tips the scales at thirty-two pounds. His color is officially designated “fawn piebald,” which means he has very pretty markings of light brown and white, about half of each. His fur is short and soft, and his large, expressive ears are light brown on the back, dark pink inside, and can seem almost translucent in the sunlight. He has a stocky, muscular body, no snout to speak of, and no tail. His eyes are deep brown, and one of them has a strabismus, meaning that it looks slightly to the left. His nose and mouth area are black, and like most bulldogs, he has a pronounced underbite. His mouth is wide and, when he’s trotting along with his pink tongue hanging out, forms a permanent smile. His face is joyful, his eyes bright, his expression either playful or craven.

I could never have imagined that Grisby’s name, chosen almost at random, would come to be so full of meaning for me. “You will likely call your dog’s name over 50,000 times,” advises the author of How to Raise and Train a French Bulldog. “Pick a name you like!” In his book Bashan and I, the German writer Thomas Mann writes that of all the pleasures he shares with his dog, none is so great for him as addressing the creature over and over again by his name. “Bashan” is the only word that Mann’s devoted and playful setter seems to understand, and his master loves driving him into crazy fits of ecstasy reminding him that not only is his name Bashan but he is Bashan, a truth the dog never seems to tire of. Grisby feels the same way; he seems to love his special name as much as I love to say it. Of course, now that we’ve been together for eight years, I can’t separate the name from the animal it signifies, and I’m irritated when people who’ve known him for years still haven’t grasped it, calling him Grigsby, Bigsby, Gribley, or Grimsby.

We name our dogs the way we name our children; we name the child we imagine having—the child we want—rather than the child we get. Bearing this in mind, there’s a lot to learn about people from the names they give their dogs. Some prefer a name they’ve heard before; others pick something they consider unique, as I did. As with baby names, fashions in dog names go in cycles. In ancient Roman households, it was trendy to give Greek names to your hounds (and your slaves). The most popular Roman dog names were descriptive: Ferox (“Savage”), Melampus (“Blackfoot”), Patricius (“Noble”), and Skylax (“Puppy”). Greek dogs were rarely saddled with the polysyllabic names of their owners (Agamemnon, Olympiodorus). Xenophon, a Greek historian who wrote about hounds in the fourth century BC, maintained that the best names are short, consisting of no more than one or two syllables, so the dogs may be easily called. Popular names were those that expressed speed, courage, and strength, such as Aura (“Breeze”), Horme (“Eager”), Korax (“Raven”), and Labros (“Fierce”).

In the United States, until around fifty years ago, dogs were generally working animals rather than household pets, and their names reflected their tasks and talents: Hunter, Skipper, Pilot, Sailor, Shep. Simple, one-syllable names like Buck, Lad, Jack, and Pal are still popular for working dogs; they’re easy for the animals to learn, and the owners to yell. Grandiose names like Caesar, Nero, and Napoleon have always been in fashion among purebred pets (and people), and descriptive names—Patch, Jet, Domino, Ginger—are still sometimes heard, though not as much as they once were. Traditional dog names like Rover and Fido are also out of fashion; these days, dogs seldom rove, and few of us speak Latin.

Today, at least in Europe and the United States, very few dogs are kept as working animals. Most pooches live in the home and sleep in their owners’ beds; their only task is to provide affection and attention, and they succeed like never before. According to a recent survey, 15 percent of British dog owners consider their pet more important than their cousin, and 6 percent confessed they even preferred their pet to their own partner. Sixteen percent listed their dogs as household members in the 2011 British census, some listing a dog as their “son” on the official form. The deeper the bond we form with our dogs, it seems, the more we make them over in our own image; in keeping with their role as full family members, dogs are now commonly given human names. Today, for the first time in history, the same names turn up in top-ten lists for both babies and dogs: Chloe, Bella, and Sophie for girls; Charlie, Jack, and Max for boys. The same trend is common in Europe, except in the more strictly Catholic countries, where it’s considered sacrilegious to call “soulless animals” by human names.

One fashion that hasn’t changed over time is the tendency for macho guys to give their tough dogs fighting names. Popular names for male pit bull terriers include Tyson, Diesel, and Tank. Other common names include Chaos, Sherman, and Panzer. In Emily Brontë’s novel Wuthering Heights, published in 1847, Heathcliff’s bulldogs, which he warns are “not kept for a pet,” are named Skulker and Throttler. It’s not surprising that he mistreats them, nor that he almost kills a spaniel, nor that a child raised in his home is seen “hanging a litter of puppies from a chair-back in the doorway.” Puppies that recover from such misfortunes are invariably named Lucky or Chance. Rocky is the most popular name for dogs that bite, according to San Francisco Health Department records, closely followed by Mugsy, Max, and Zeke.

We fall in love with individual dogs, but it’s difficult to separate the dog from the breed, and it’s not unusual, with dogs as with lovers, that we should fall repeatedly for the same kind. The standard poodle has always been popular with literary and philosophical types. In addition to Schopenhauer and Gertrude Stein, poodle lovers include Victor Hugo, Lillian Hellman, George Sand, Norman Mailer—who once got into a street brawl with a man who called his poodle “a queer”—and John Steinbeck, whose standard poodle Charley was his close companion for many years, and costar of his 1962 book Travels with Charley. However, outranking even the poodle among literary and artistic types is the dachshund (see LUMP and QUININE), breed of choice for Henry James, Matthew Arnold, Dorothy Parker, G. K. Chesterton, Anton Chekhov, Vladimir Nabokov, Pablo Picasso, and David Hockney, among others. Dachshunds are said to be complex, vulnerable, and fussy, and they’re often described as having an “artistic temperament.” Like dog, like master.

In light of my feelings for Grisby, I find it hard to imagine owning any breed other than the bulldog. As the only dog I’ve ever known, Grisby is my Atma, the universal soul of dog, the ideal essence, which, according to Schopenhauer’s Platonic notion of true forms, exists both before and after each imperfect manifestation. Plato would disagree; he’d claim that only the idea of the dog is real, and Grisby is a flawed copy of the unchangeable and original essence. But how could he know? As far as I’m aware, Plato didn’t have a warm bulldog on his lap, licking his knees as he wrote.