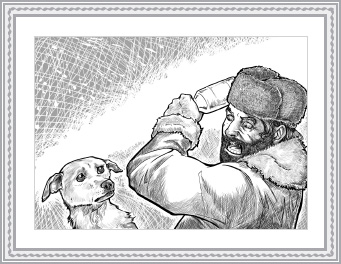

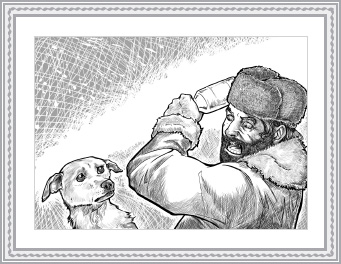

KASHTANKA, THE EPONYMOUS subject of a short story by Anton Chekhov first published in 1887, is a mutt—“a reddish mongrel, between a dachshund and a ‘yard-dog,’ very like a fox in the face.” She’s lived her whole life with a drunken carpenter and his nasty son, both of whom treat her cruelly. The carpenter shouts at her angrily, “Once he had even, with an expression of fury in his face, taken her fox-like ear in his fist, smacked her, and said emphatically: ‘Pla-a-ague take you, you pest!’” One day, thanks to the carpenter’s carelessness, Kashtanka gets lost in the bleak city streets. Freezing and hungry, she huddles down in the doorway of an inn. “If she had been a human being,” the narrator observes, “she would certainly have thought ‘No, it is impossible to live like this! I must shoot myself!’”

Fortunately, a kindly stranger adopts her; feeds her bread, cheese, meat, and chicken bones; and gives her a mattress to sleep on. This stranger, a circus performer, gives her the name Auntie, and introduces her to his other animals: a pig, a white cat, and a goose. When the goose dies, Kashtanka is taught a number of tricks so she can take its place in their performance. A few months later, the sleek and well-fed Kashtanka is in the middle of her circus routine when she spots her former owners in the audience. Gleefully, she leaps from the stage and runs to them, happily returning to her former life of abuse and privation. Before long, “the delicious dinners, the lessons, the circus . . . all that seemed to her now like a long, tangled, oppressive dream.”

Like similar stories involving animals, “Kashtanka” is regularly found in anthologies of tales for children. While it’s true that youngsters are often fascinated by animals, there’s a widespread assumption that “animal stories” are written for the young, as if no mature adult could be interested in a story told from the point of view of a dog. One adaptation of the story available on Amazon, colorfully illustrated, is placed in the age range “8 and up,” and the book is summarized as “a quietly sentimental tale of a lost dog.” “Children will respond well to the endearing return of a lost pet,” notes a reviewer in the School Library Journal, and an otherwise enthusiastic reader takes the trouble to warn parents that “one character dies of natural causes midway through.”

Yet “Kashtanka” isn’t meant for children. It’s a painful tale that asks some very difficult questions about happiness and familiarity. Is it instinct that compels Kashtanka to return to her former life? After she first leaves home, trying to get to sleep one night, she recalls with an “unexpected melancholy” the things the carpenter’s son used to do to her, including one “particularly agonizing” trick: “Fedyushka would tie a piece of meat to a thread and give it to Kashtanka, and then, when she had swallowed it he would, with a loud laugh, pull it back again from her stomach.” Nevertheless, “the more lurid were her memories the more loudly and miserably Kashtanka whined.” Why would anyone feel nostalgic for such abuse? Is Kashtanka so deprived that she regards even cruelty as desirable attention? How do dogs think about such matters, if they think about them at all?

Perhaps the familiarity of Kashtanka’s former life, despite its privation, provided her with a kind of contentment; I’ve definitely noticed that once Grisby gets used to something—even if it’s something he dislikes, such as taking a bath or getting his nails clipped—he comes to accept it stoically, even compliantly. It’s well known that women return again and again to their abusive partners, and prison inmates eventually get used to their daily routines. Children brought up in captivity or isolation often find the outside world threatening, and are drawn to the safety of small enclosures. Perhaps, in some ways, we all prefer what we know.

I suppose it’s possible that Kashtanka returns to her original master because he allowed her more independence than the circus performer, who keeps her on her toes with a daily routine of lessons and rehearsals, though we’re told that “she learned very eagerly, and was pleased with her own success.” Companionship and a daily routine ought to make her happy; in their natural state, after all, dogs live their entire lives within the closely structured social order of their pack, which suggests they understand and even seek out dominance and leadership. In her book The Companion Species Manifesto, the cultural theorist and dog agility trainer Donna Haraway, pondering what happiness means for a companion animal, concludes that it is “the capacity for satisfaction that comes from striving, from work, from fulfillment of possibility . . . from bringing out what is within.”

If Haraway is right and dogs need to work to their full capacity, then Grisby must be pretty miserable. He doesn’t have the opportunity to “strive” every day, perhaps not even to exercise as much as he’d like to, certainly not to satisfy his capacity for “fulfillment of possibility.” According to this argument, Grisby, like Kashtanka, prefers his confinement because it’s the only thing he knows. Overweight, neutered, and idle, he’s never had the joys of hunting down his own dinner or chasing a female in heat. He’s addicted to his captivity, like the Pekingese dogs owned by prostitutes in old Shanghai that acquired opium habits from breathing in the smoke of their mistresses’ lamps. Still, there’s a kind of arrogance, I think, in the suggestion that a dog like Grisby must be living an unfulfilled life because he’s not living to his “maximum capacity.” (To be honest, how many of us are?) The argument doesn’t take account of his intelligence and flexibility (figuratively speaking—in the flesh, not so much). It seems wrong not to read his displays of excitement and exuberance as indications of pleasure, just as it would be wrong not to read his whimpers and whines as signs of pain.

His repertoire of noises, moreover, is remarkably expressive. His snorts and grunts seem to signal curiosity and contentment, and the other sounds he makes seem equally meaningful. When something’s bothering him—when an object’s temporarily out of place, for example, or when there’s a bag of trash in the room—there’s a noise he makes with his lips pursed cautiously that sounds exactly as if he’s trying to articulate the word “woof.” There’s a deep sigh of resignation or satisfaction he makes when settling down for a nap, and a weary inward-outward exhalation that sounds as if he’s saying, “Oy vey!” When tickled, he makes breathy, openmouthed panting sounds that bear a very close resemblance to laughter, and when he’s tired, a series of noisy, cavernous yawns form the overture to his snoring symphony.

In the following situations, I find it difficult to believe Grisby isn’t feeling something very close to what we humans call “happiness”: when, at the park, I unhook his leash and he goes charging off on the trail of a rabbit or squirrel; when he runs through long, damp grass in the sunshine; when he gets to join human games of Frisbee or soccer; when he chases skateboarders and barks at their boards; when, in spring, he rolls around in fallen blossoms; when he charges up and down with his head in the air; when he noisily wolfs down his dinner; when he bounces down the street on a warm morning, spreading his bulldog bounty; and, not least, when I come through the door on those rare occasions when I’ve had to be away from him all day. Once, when I came home unexpectedly, he ran around the dinner table three times. Exuberant joy at my return certainly seems the most obvious reading of his behavior, though I must admit, it’s also the most flattering. It’s hard to escape the common assumption that, emotionally speaking, dogs are easier to understand than people. “Animals are more unrestrained and primitive, less subject to inhibitions of all kinds,” Thomas Mann argues, “and therefore in a certain sense more human in the physical expression of their moods than we are.” Darwin makes a similar observation. “Man himself,” he wrote, “cannot express love and humility by external signs so plainly as does a dog, when with dropping ears, hanging lips, flexuous body, and wagging tail, he meets his beloved master.”

Then again, maybe Kashtanka ran around the table three times, too, when the drunken carpenter and his son got home. Maybe that’s just what dogs do. Maybe Grisby hasn’t had enough experience to fully discriminate between routine and happiness. I wonder: If he were unhappy, would I know it? Would he know it? And if we can be unhappy without knowing it, what does it really mean to be unhappy? These are questions it’s impossible to answer. However deep my bond with Grisby may be, the absence of a shared language will always come between us. When he clearly wants something and I’ve tried all the usual things—food, water, treats, petting, a kiss, a scratch, a walk—I look into his eyes, so intelligent and expressive, and it suddenly seems baffling that he can’t just tell me what he wants.

French author Maurice Maeterlinck disagrees that we’re separated from dogs by their lack of language. His short essay “Our Friend the Dog,” first published in 1903, begins with an epitaph for his “little bull-dog” Pelléas, who has just died at the tender age of six months. From the time he spent with this loving animal, Maeterlinck came to feel that, of all creatures, the dog “succeeds in piercing, in order to draw closer to us, the partitions, ever elsewhere impermeable, that separate the species!” In other words, according to Maeterlinck, the lack of a shared language actually enhances the human-canine relationship. Perhaps it’s true. In the absence of language, it’s fine for me to kiss Grisby’s head, paws, and nose and the insides of his ears; to wash his bottom, clean out his wrinkles, and wipe away his drool. Language would make this kind of thing a little uncomfortable. He could, after all, ask me to stop, which is what children do when they get old enough. Perhaps, rather than translating dog thoughts into human words, we should be wondering, as Alice A. Kuzniar suggests in her book Melancholia’s Dog, “how to preserve, respect and meditate on the dog’s muteness and otherness.”

Language, for all its benefits, is also a source of great pain. It’s language that brings awareness of time, memory, and death. Language creates the scrim of consciousness that separates us from other beings. Language gives us the capacity to dwell on the past, to anticipate the future. Without language, we’d be living like animals, in the perpetual present, outside time, unaware of death. The impossibility of our returning to this state is something many philosophers have tried to grapple with (“If a lion could speak,” according to Ludwig Wittgenstein, “we would not understand him”). In an essay on humanism, the philosopher William James speculates on the connection between language and thought. “To call my present idea of my dog . . . cognitive of the real dog,” he wrote, “means that, as the actual tissue of experience is constituted, the idea is capable of leading into a chain of other experiences on my part that go from next to next and terminate at last in vivid sense-perceptions of a jumping, barking, hairy body.”

Jumping, barking, hairy bodies have no need to speculate about “the actual tissue of experience”—they’re too busy having it. Dogs, unlike philosophers, never doubt. “A dog cannot lie, but neither can he be sincere,” claimed Wittgenstein, who clearly never had a dog. Grisby is always sincere, and so was Pelléas, whom Maeterlinck describes in “Our Friend the Dog” as a young bulldog with a generous and gentle nature. Maeterlinck recalls Pelléas, though still a small puppy, “sitting at the foot of my writing-table, his tail carefully folded under his paws, his head a little on one side, the better to question me, at once attentive and tranquil, as a saint should be in the presence of God.” To Maeterlinck, a dog’s unthinking love and devotion to its master turns human beings into divinities, of whom the dog possesses full knowledge. “I envied the gladness of his certainty,” wrote Maeterlinck of Pelléas. “I compared it with the destiny of man, still plunging on every side into darkness, and said to myself that the dog who meets with a good master is the happier of the two.”

Clearly, human language is artificial, impractical, and absurd when compared with “a jumping, barking, hairy body,” or the solid certainty of a bulldog at your feet. Virginia Woolf wrote of Flush that “not a single one of his myriad sensations ever submitted itself to the deformity of words,” yet the author needs “the deformity of words” to describe the dog’s life, to translate it into a story we can understand. Flush is a book for humans; dogs don’t have stories. On this subject, William James, in an essay entitled “A Pluralistic Universe,” speculates that “we may be in the Universe as dogs and cats are in our libraries, seeing the books and hearing the conversation, but having no inkling of the meaning of it all.” But why assume “the meaning of it all” is something contained in books? Words can’t be chewed, chased, or licked; they can’t be eaten, growled at, or pissed on; they have no smell; for those of us without language, what use are they at all?