HOWARD SKLAMBERG AND JENNIFER DEVINE

THE U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has traditionally been a domestically focused agency, for which Congress kept the regulatory lens narrow in scope with oversight of industry being concentrated on those companies within U.S. boundaries. Over the past decade, FDA’s responsibilities have changed rapidly because of globalization of the supply chain, the exponential growth in imports that has followed, and the increasing breadth and complexity of FDA-regulated products resulting, in part, from scientific innovation. Decades ago, it was likely the drugs in your medicine cabinet would have come from a domestic source, but now, the reality is that they could just as easily have been made abroad or contain ingredients or components sourced from abroad. While this chapter is primarily focused on pharmaceuticals, it is important to note that this example holds true across the health and nutrition spectrum, from food to medical devices to drugs, and has set forth a new reality—a global regulatory environment for FDA. This ever evolving environment requires FDA to deepen collaborations and partnerships globally with other regulatory and public health partners—nationally and across borders—to ensure it meets its public health mission.

I. GLOBAL AND INNOVATIVE REGULATORY ENVIRONMENT

Today, the percentage of imported products consumed continues to increase, and the distinction between foreign and domestic products has become increasingly blurred—to the point of irrelevance (Food and Drug Administration 2011). FDA regulates products that account for approximately 20 percent of every consumer dollar spent in the United States (Food and Drug Administration 2015). FDA-regulated products originate in 300,000 foreign facilities in more than 150 countries, and the volume of imports to the United States has increased nearly fivefold, from 6 million product lines in 2001 to an estimated 30 million in 2014. Eighty percent of seafood consumed in the United States comes from abroad, as does 50 percent of fresh fruits and 20 percent of vegetables (ibid). For medications, approximately 40 percent of listed finished drugs come from overseas, and 80 percent of the manufacturers of active ingredients are located outside the United States (ibid.). In addition to the increasing volume of products sourced from abroad, the supply chain from manufacturer to consumer has become more and more complex, involving a web of manufacturers, suppliers, packagers, and distributors (Hamburg 2010). Risks associated with this complex supply chain are compounded by advances in technology and manufacturing, as well as language barriers, time differences, and distances. At every step in the process—from raw materials and other ingredients to manufacture, storage, sale, and distribution—a product can be contaminated, diverted, counterfeited, or adulterated.

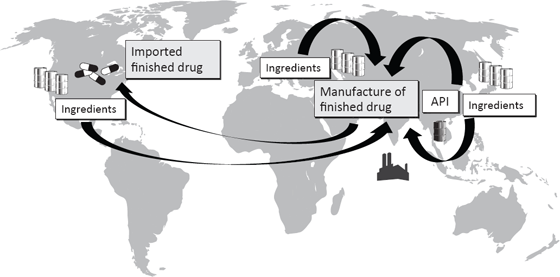

This has made FDA oversight increasingly complicated because there are numerous individuals and firms in the supply chain that are geographically dispersed with varying levels of rigor in their regulatory systems. In the following example, a finished drug was produced with an active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) made in China and inactive ingredients (excipients) made in Europe, Japan, and the United States. These components were then shipped to India, where the finished drug was manufactured and then imported into the United States for distribution. The quality of both drug components and finished forms can be compromised at various points in the supply chain. Any individual or firm involved might knowingly introduce adulterated components or unknowingly use substandard ingredients. The Internet—and the anonymity it confers—presents an additional layer of complexity by introducing more players into the system (Sklamberg 2014).

Figure 2.1 Global Drug Manufacturing Supply Chain Example

This illustration gives an example of a drug manufacturing supply chain. A finished U.S. drug may be produced using an active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) made in China and excipients made in Europe, Japan, or the United States. These components may be shipped to India, where the finished drug is manufactured and then imported into the United States for distribution.

Unfortunately, there have been numerous examples of what can happen in these highly complex supply chains. Fever medicine, cough syrup, and teething products have been adulterated at one time or another with diethylene glycol, a toxic solvent found in antifreeze. Over the last twenty years, such adulterated products are thought to have caused an estimated 570 deaths worldwide, including children and adults in Haiti, Panama, and Nigeria (Autor 2011). In 2007, Chinese suppliers of wheat gluten substituted melamine, an ingredient used in making plastic, which proved toxic when it was used in U.S. pet food and dairy products. The contaminated food sickened and killed pets across the United States and put many people at risk (Hamburg 2013). Also in 2007, Chinese suppliers of heparin, a drug critical to the prevention of blood clots, substituted a lower cost, adulterated raw ingredient in their shipments to U.S. drug makers, causing deaths and severe allergic reactions (ibid.).

While it may not eliminate all problem products from the supply chain, a relatively comprehensive system of laws, regulations, and enforcement has kept supply chain incidents comparatively rare in the United States. Despite the infrequency of such incidents and FDA’s continuous modernization and evolution, the heparin situation of 2007 and 2008 was a wake-up call forcing not only FDA but also other stakeholders to think more critically and foundationally about the vulnerabilities of the current regulatory environment. The incident pointed to the need to deepen collaborations and partnerships globally—internally, nationally, and across borders—to help regulate in the complex and evolving global environment. It also highlighted and galvanized stakeholders to work with Congress to pass legislation to help stakeholders navigate the realities of innovation, modernization, and globalization.

II. LEGISLATIVE AUTHORITIES

Congress has modified and expanded FDA’s regulatory authorities in recognition of the globalization of the supply chain and the subsequent growth in imports, scientific innovation, and the increasing breadth and complexity of FDA-regulated products. FDA is implementing these new mandates and leveraging additional authorities in an effort to continue to meet its public health mission. Some of the major legislation Congress has recently passed included the FDA Food Safety and Modernization Act, the Food and Drug Administration Safety and Innovation Act, and the Drug Quality and Security Act.

A. The FDA Food Safety and Modernization Act (FSMA)

Every year, approximately one in six Americans suffers from a foodborne illness (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2014). The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates an annual total of 48 million illnesses, 128,000 hospitalizations, and 3,000 deaths (ibid.). Under FSMA (Pub. L. No. 111-353), FDA is creating a modernized food safety system that, when fully implemented, should reduce the number of food-related illnesses. This law requires that FDA establish prevention-oriented standards that cover each stage of the food supply chain and grants FDA new administrative tools to hold all parties in the supply chain responsible for the production and distribution of safe food for humans and animals (including pet food and nonmedicated animal feed).

FDA has proposed FSMA-mandated rules that, when final, will establish the comprehensive framework of modern, prevention-oriented standards mandated by FSMA, from the grower of fresh produce, to food and feed manufacturers and processors, through the transportation to retail of foods and feeds produced in the United States or overseas and consumed in the United States. FSMA allows for the creation of an imported food safety system that enables FDA to hold imported foods to the same standards as domestic foods. Importers now have a responsibility to demonstrate the safety of the food they bring into the United States (Food and Drug Administration 2014a). In addition, FSMA mandates that FDA collaborate with and leverage other government agencies, both domestic and international. The statute explicitly recognizes that all food safety agencies need to work together in an integrated way to achieve shared public health goals (ibid.). Under these provisions, FDA is working to leverage the efforts of local, state, and foreign government counterparts (ibid.). FDA continues to work on implementing FSMA and its new authorities.

B. The Food and Drug Administration Safety and Innovation Act (FDASIA)

Complementing its new legislative authorities for foods, FDA is implementing several new authorities to help further ensure the safety and integrity of drugs imported into and sold in the United States. In 2012, Congress passed the Food and Drug Administration Safety and Innovation Act (FDASIA), expanding FDA’s authorities and strengthening the agency’s ability to safeguard and advance public health by giving it the authority to collect user fees from industry to fund reviews of innovator drugs, medical devices, generic drugs, and biosimilar biological products; promoting innovation to speed patient access to safe and effective products; increasing stakeholder involvement in FDA processes; and enhancing the safety of the drug supply chain (Pub. L. No. 112-144). FDASIA built on previous foundational legislation—like the FDA Modernization Act (FDAMA), which enabled FDA to begin to work internationally to strengthen standards when setting forth specific drug supply chain provisions.1

FDASIA Title VII strengthens drug safety by giving FDA new authority to protect the integrity of an increasingly global drug supply chain, for example, by increasing FDA’s ability to collect and analyze data to enable risk-informed decision making, advancing risk-based approaches to facility inspections, partnering with foreign regulatory authorities, and driving safety and quality throughout the supply chain through strengthened enforcement tools.

The law provides FDA with the authority to administratively detain drugs believed to be adulterated or misbranded (Section 709) and the authority to destroy certain adulterated, misbranded, or counterfeit drugs offered for import (Section 708). The law also requires foreign and domestic companies to provide additional firm registration and drug listing information to ensure that FDA has accurate and up-to-date information about foreign and domestic manufacturers (Sections 701–703, 714). In addition, the law gives FDA the ability to work with foreign governments in a number of different capacities.

Since enactment of FDASIA, FDA has been working diligently to implement the Title VII supply chain authorities in a meaningful way that strives to maximize its public health impact. To date, FDA issued a proposed and final rule to extend the agency’s administrative detention authority to include drugs intended for human or animal use, in addition to the authority that is already in place for foods, tobacco, and devices; issued a proposed rule regarding administrative destruction of imported drugs refused admission into the United States; issued draft and final guidance defining conduct that the agency considers delaying, denying, limiting, or refusing inspection, resulting in a drug being deemed adulterated; issued draft and final guidance addressing specification of the unique facility identifier system for drug establishment registration; and successfully worked with the U.S. Sentencing Commission on higher penalties relating to adulterated and counterfeit drugs (Food and Drug Administration 2014c). The agency had already taken steps toward development of a risk-based inspection schedule, before FDASIA. However, the enhancements provided by FDASIA will further assist the agency in responding to the complexities of an increasingly globalized supply chain.

In addition, FDA hosted a public meeting in 2013 and also requested written comments (78 Fed. Reg. 36,711 (Jun. 19, 2013)) to solicit feedback from the public about implementation of Title VII generally and to specifically address the provisions related to standards for admission of imported drugs and commercial drug importers, including registration requirements and good importer practices (Food and Drug Administration 2013). FDA continues to work on implementing FDASIA Title VII, prioritizing its efforts to achieve the greatest public health impact and deploy its limited resources most effectively.

C. The Drug Quality and Security Act (DQSA)

The Drug Quality and Security Act was signed into law in 2013 and provided a significant step toward having new and stronger drug quality and safety laws. The law enhances FDA’s oversight of certain entities that prepare compounded drugs and enables certain prescription drugs to be traced as they move through the U.S. drug supply chain.

Specifically, Title II of DQSA, the Drug Supply Chain Security Act (DSCSA), outlines critical steps to build an electronic, interoperable system to identify and trace certain prescription drugs as they are distributed in the United States by 2023. DSCSA aims to facilitate the exchange of information to verify product legitimacy, enhance detection and notification of an illegitimate product, and facilitate product recalls. Drug manufacturers, wholesale drug distributors, repackagers, and many dispensers (primarily pharmacies) will be called on to work in cooperation with the FDA to develop the new system over the next nine years.

The law requires the FDA to establish standards, issue guidance documents, and develop a pilot program(s), in addition to other efforts, to support effective implementation and compliance. In 2014, the FDA issued a draft guidance on identifying suspect drug products in the supply chain and notification, and a draft guidance on establishing standards for the interoperable exchange of transaction information for trading partners (Food and Drug Administration 2014b).

III. GOING FORWARD: POSITIONING FDA TO OPERATE IN A GLOBAL AND INNOVATIVE REGULATORY ENVIRONMENT

Scientific innovation, globalization, and the increasing complexity of regulated products as well as new legal authorities provide FDA a unique opportunity to improve oversight of regulated products. Building on its long history of adaptation to fulfill its mission, FDA is moving forward and taking the necessary measures to ensure it is fully prepared to operate in this new dynamic environment.

A. Global Regulatory Operations and Policy Directorate

In June 2011, the commissioner of the FDA established the Global Regulatory Operations and Policy Directorate (GO) to provide oversight, strategic leadership, and policy direction to FDA’s domestic and international product quality and safety efforts. The GO directorate includes the Office of Regulatory Affairs (ORA) and the Office of International Programs (OIP). ORA and OIP are responsible for conducting domestic and foreign inspections and advancing FDA’s global engagement work, including deepening collaborations with local, state, federal, and foreign regulatory and public health partners. Since its inception, GO has been working steadily to further develop a global product “safety net” that protects public health. GO is engaged in a variety of activities, internally and externally, to support its mission of advancing FDA’s role as a modern public health regulatory agency.

B. FDA’s Program Alignment

FDA is also working internally to achieve greater operational and programmatic alignment. Recognizing that the agency must change in fundamental ways to adapt to this new globalized climate, in 2013, Commissioner Hamburg instituted a Program Alignment Group to identify and develop plans to modify agency compliance and regulatory functions and processes in order to address the challenges associated with globalization and achieve mission-critical agency objectives (Food and Drug Administration 2014e). The overarching goal of program alignment is for the agency to modernize and strengthen the way it fulfills its public health role by changing how its inspectional workforce is organized, from alignment by domestic regions to distinct commodity-based and vertically integrated regulatory programs with a focus on specific product areas, such as pharmaceuticals, food, animal feed, medical devices, biologics, or tobacco.

The FDA Directorates, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the ORA have been collaborating closely to define the changes that need to be made in order to align FDA more strategically and operationally to meet the greater demands placed on the agency. As a result, each regulatory program has established detailed action plans that identify critical actions needed to jointly fulfill FDA’s mission in the key areas of specialization, training, work planning, compliance policy and enforcement strategy, imports, laboratory optimization, and information technology (ibid.).

C. Developing a Proactive Approach on Trade

Spurred by globalization and innovation, we have reached a turning point where trade, economic development, and global health intersect as never before. For FDA-regulated products, many goods and services are no longer sourced from one supplier; product development and distribution come from multiple sites in multiple countries. FDA understands that, in order to be effective in a dynamic, globalized world, the agency must take an active approach toward its engagement with the global public health and trade policy arenas. Thus, FDA has established an Office of Public Health and Trade (OPHT) in the OIP and has embarked on a new approach of active engagement that uses FDA’s scientific, technical, and policy expertise to champion science-based regulation as a critical enabler of trade globally. This approach seeks to develop more cohesive strategies and policies relevant across FDA-regulated commodities and assure product safety and quality and stronger supply chains while promoting increased market access for U.S. exporters, increased trade, and enhanced economic development in low- and middle-income countries. The establishment of OPHT/OIP consolidates responsibility for policy coordination for FDA inputs into trade negotiations in one office and helps establish clear, coordinated, and consistent policy positions on significant issues related to trade. By ensuring a central, unified approach, FDA has a heightened opportunity to shape consistent, meaningful obligations under free trade agreements to support FDA’s regulatory approaches and public health mission.

D. FDA’s International Presence

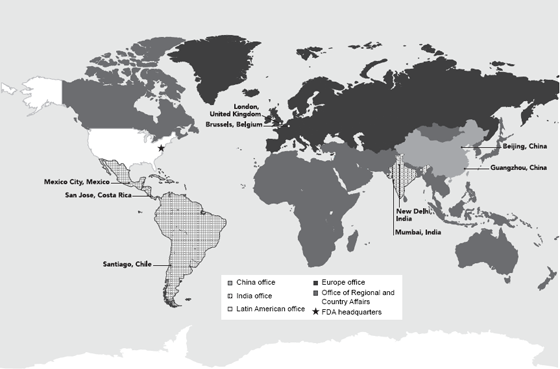

In 2008, FDA received a special U.S. congressional appropriation to establish offices overseas and opened the first office in China the same year. Today, FDA’s nine posts in seven countries on four continents provide the agency with the ability to work more closely with foreign regulators and industry and to educate foreign stakeholders about FDA standards, regulations, and procedures. FDA’s strategically placed locations enhance its ability to build mutually beneficial relationships with foreign counterparts; gain a greater understanding of the host country’s regulatory, public health, cultural, security, economic, and geopolitical landscape; and identify any developments in these arenas that may affect the quality, safety, or availability of FDA-regulated products bound for the United States.

Figure 2.2 FDA Foreign Posts

Source: Food and Drug Administration 2015.

FDA also has a foreign inspectorate consisting of a dedicated cadre of staff members whose sole job is to conduct inspections internationally. Currently, foreign inspections are being conducted by FDA staff in the United States and in Latin American, Chinese, and Indian foreign posts. The presence of FDA staff in foreign offices throughout the world and the increased emphasis on international inspections have led to greater oversight of foreign regulated commodities. In addition, the establishment of foreign posts, combined with a variety of other activities led by FDA staff in the United States, has enhanced FDA’s ability to deepen its collaborations and partnerships around the globe.

E. Deepening Our Global Collaborations and Partnerships

Hundreds of thousands of entities worldwide are processing, manufacturing, producing, and distributing FDA-regulated products for the U.S. market. These entities use increasingly diverse and complicated processes and manage complex and extended supply chains. The burgeoning scale and complexity of the innovative global regulatory system make it difficult for FDA to meet its public health mission on its own or by employing historic approaches and tools that were often limited to a domestic focus, such as checking shipments at the U.S. border or seizing product within the United States. FDA’s success depends on working with other federal agencies and state, local, and international stakeholders.

FDA has worked collaboratively throughout its history with local, state, and federal agencies in a number of different areas including establishing national standards; developing and delivering training and certification programs to ensure a highly skilled workforce; developing mechanisms to share information; creating and executing laboratory proficiency programs; and responding quickly to problems related to regulated products. To complement these national efforts, FDA has worked internationally in formal and informal dialogues and through developing collaborative relationships among regulatory colleagues and international organizations. These global engagements have been helpful in building relationships with counterparts and exchanging or sharing information. FDA intends to continue to build on these relationships and focus on meaningful collaborations that leverage knowledge and resources. Following are some examples of FDA’s many collaborations and partnerships from a medical product perspective; similar efforts are ongoing within the food commodity area at FDA. These collaborations and partnerships usually relate to information sharing, harmonization/convergence, and mutual reliance/oversight efforts.

As collaborations and partnerships increase, so does the need for timely exchange of scientific and regulatory data and approaches. FDA continues to explore areas for alignment with global stakeholders in an effort to increase knowledge and understanding and allow regulatory agencies and other stakeholders to leverage their ability to detect, prevent, and respond to public health concerns.

FDA has long promoted engagements with regulatory counterparts related to information sharing through binding and nonbinding agreements. FDA has entered into more than 135 international arrangements with counterparts around the world that enable sharing of scientific knowledge, expertise, standards, regulations, and, in some cases, inspection or other nonpublic information (Food and Drug Administration 2014d).

In addition to these agreements, FDA has been supporting and working on numerous multilateral information-sharing platforms. For example, the Pan American Health Organization launched the Regional Platform on Access and Innovation for Health Technologies (PRAIS), an information hub to facilitate medical product data sharing in the Americas, serving as a regional model of a data-sharing system and network that can be expanded globally. The platform can enable an environment for regulatory exchange. FDA also supported a World Health Organization (WHO) multiregional platform for monitoring substandard, spurious, falsely labeled, falsified, and counterfeit (SSFFC) medical products to help improve data sources and collection methodologies globally. This global monitoring system is a means to share information on a global scale regarding counterfeit medical products. These information-sharing collaborations are an important aspect of FDA’s efforts to leverage scientific and regulatory expertise and encourage others to do so as well.

G. Mutual Reliance/Recognition

Launched in May 2014, the Mutual Reliance Initiative is a strategic collaboration between the FDA and European Union (EU) to evaluate whether reliance on each other’s inspection reports of human drug manufacturing facilities is possible. Strengthening reliance upon each other’s expertise and resources will result in greater efficiencies for both regulatory systems and provide a more practical means to oversee the large number of drug manufacturing sites outside of the U.S. and EU. Both the FDA and EU have dedicated teams to assess the risks and benefits of entering into a mutual reliance agreement.

In this context, the term “mutual reliance” means that the EU and member state authorities and FDA would rely upon each other’s factual findings from manufacturing quality/Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) inspections to the greatest extent possible and generally not re-inspect a facility already inspected by the other party unless special circumstances exist. However, because of the differing legal systems and other factors, from time to time, the U.S. and EU might come to different conclusions about an application or enforcement action, and in such situations each would exercise the right to make its own decisions.

A mutual reliance agreement ultimately would allow both the FDA and EU authorities to reallocate and leverage limited resources to increase oversight of manufacturing operations with potentially higher risk to quality and safety and thus to public health, not only within our respective regions, but also in other parts of the world that manufacture pharmaceuticals for the U.S. and EU markets. This collaboration and redeployment of resources would benefit patients, as well, by refocusing efforts to better address problems before they result in adverse public health outcomes.

H. Harmonization and Convergence

FDA has a long history of supporting and participating in harmonization efforts of scientists and regulators. FDA is working through multilateral harmonization efforts such as the International Medical Device Regulators Forum (IMDRF) and the International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH) to ensure the broadest possible reach of science-based standards and guidelines. FDA’s participation in these multilateral harmonization efforts is significant and ongoing. For example, medical device regulators built upon the strong foundational work of the Global Harmonization Task Force on Medical Devices (GHTF)2 and established the IMDRF (International Medical Device Regulators Forum 2014). This new forum has an expanded membership of regulatory bodies, observer organizations, and related communities and is moving toward greater international uniformity and convergence in regulatory practices for medical devices. The ICH originally brought together the regulatory authorities and pharmaceutical industries of Europe, Japan, and the United States to increase harmonization in the interpretation and application of technical requirements for drug marketing approvals. Over time, the group has gradually evolved to become more global in nature, inviting observer organizations and interested parties into the discussion. Altogether, ICH has developed more than sixty harmonized guidelines aimed at eliminating duplication in the development and registration process. FDA is now involved in harmonization efforts in most regulated product areas. These harmonization efforts involve aligning different countries on science-based regulatory standards for the quality, safety, and efficacy of imported and exported products. Harmonization helps governments realize efficiencies in developing, implementing, and enforcing standards.

I. International Coalition

In addition to these ongoing initiatives related to information sharing, mutual reliance, and harmonization, an effort under development is the newly established International Coalition of Medicines Regulatory Authorities (ICMRA), which is a voluntary, senior-level, strategic coordinating, advocacy, and leadership entity that provides direction for a range of areas and activities that are common to many regulatory authorities’ missions and goals. The ICMRA is anchored in the recognition by regulators of the need to address current and emerging human medicine regulatory and safety challenges globally, strategically, and transparently in ways where collective approaches and collaboration expand the regulatory reach of any one regulator in effective and sustainable ways. Over time, ICMRA will enable a global framework in which ICMRA participants will work on selected joint initiatives to stimulate collective thinking and action; pilot new ways of working to build mutual reliance; and facilitate early and timely identification of emerging public health crises that intersect with medical regulatory authorities, resulting in a coordinated, multilateral response to such crises.

F. Strengthening Regulatory Systems

The increase in global trade highlights the need to strengthen regulatory systems. FDA has had a century to develop its regulatory infrastructure, but many countries are still in the early stages of building theirs. Stronger regulatory systems will be increasingly important to FDA’s ability to fulfill its mission to ensure the safety of the increasing volume of food, feed, medical products, and cosmetics that enter the United States from around the world. According to an Institute of Medicine study commissioned by FDA, Ensuring Safe Foods and Medical Products Through Stronger Regulatory Systems Abroad, the fundamental elements of regulatory systems are that they are independent, predictable, and recognize, collect, and transmit evidence when breaches of law occur (Institute of Medicine of the National Academies 2012). The report highlights these core elements that every system, rich or poor, should ideally have and makes recommendations for increased attention to them by the international community.

The international community increasingly recognizes the importance of strong regulatory systems. The Pan American Health Organization’s (PAHO) Directing Council passed a resolution on strengthening regulatory systems in 2010 (Pan American Health Organization 2010), and at the 2012 World Health Assembly, member states passed a resolution that will facilitate international collaboration on SSFFC (World Health Organization 2012). Most recently, the United States cosponsored a resolution on strengthening regulatory systems that went to the World Health Assembly in May 2014. This resolution was based on collaborative work among FDA, WHO, and other member states, including Australia, Nigeria, South Africa, Mexico, and Switzerland. The resolution called for WHO to continue to support countries in the area of strengthening regulatory systems; to integrate regulatory systems into health systems’s strengthening efforts; and to support subregional and regional networks to build regulatory capacity and cooperation.

Partnerships are also emerging. For example, FDA works in partnership with the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the World Bank, the African Union, and others in support of the African Medicines Regulatory Harmonization (AMRH) initiative, which seeks to speed product registrations and improve market access and safety surveillance for critical medicines and vaccines. FDA is also providing support to PAHO to explore the potential of developing a Caribbean-wide regulatory system. Because many countries in the Caribbean are small, they are not able to perform critical regulatory functions on their own (e.g., marketing authorization, etc.), and some do not have regulatory authority over medicines. The building blocks for a Caribbean-wide regulatory system are already in place. The Caribbean has implemented regional coordination mechanisms through, for example, the Caribbean Community and Common Market and established a regional public health agency that includes a regional drug testing laboratory. Ministers of health also approved a Caribbean Pharmaceutical Policy in which implementing a subregional regulatory system is a priority. The broader context is that such a regional approach can be a model for how to sustainably build regulatory capacity in other parts of the world where there are similar resource constraints.

The 2012 Institute of Medicine report Ensuring Safe Foods and Medicines Through Stronger Regulatory Systems Abroad also recommended the development of a global curriculum of fundamental regulator competencies in response to the identified lack of high quality and consistent training for food and drug regulatory staff in ensuring food and drug safety across the globe, particularly in low- and middle-income countries. Acting on this recommendation, FDA partnered with key stakeholders, including WHO, PAHO, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the Regulatory Affairs Professional Society (RAPS), the International Food Protection Training Institute (IFPTI), and the Drug Information Association (DIA), to begin a discussion about the task of developing a global curriculum that governments, multilateral organizations, educational institutions, and others could use to train food and drug regulatory staff, particularly in low- and middle-income countries. The group subsequently wrote and published a stakeholder discussion paper in June 2013 (Preston 2013) and then began an effort to produce basic competencies that could lead to the development of a general global curriculum. This collaboration, led by RAPS and IFPTI, is scheduled for completion at the end of 2015. Its goal is to strengthen the skills of critically important regulatory professionals. By defining essential competencies and then developing curriculum modules, this project can meet the needs of different countries and regions, whether low resourced or not, and can adapt to changing science and technology.

IV. CONCLUSION

The vast and complex public health and regulatory panorama outlined in this chapter may appear daunting. However, we believe FDA is ready; indeed, for some time, the agency has moved in to address global regulatory challenges. Commissioner Hamburg noted, “Our job requires greater coordination of regulatory standards and practices across nations to ensure safety and quality, regardless of where a product is produced. We are working through bilateral and multilateral agreements, as well as through international organizations, specialized partnerships and various coordinating bodies. And at the highest levels, we have embarked on creating a new model or framework for global governance” (Hamburg 2014). This ongoing work complements the significant legislative authority received by the agency in the past two years.

Moreover, for some time, FDA has been reorganizing its structure to transform from a domestic agency operating in a globalized world to a truly global agency fully prepared for a complex regulatory environment that takes into account the risks across a product’s life. We know this requires information and workload sharing with the help of regulatory partners, data-driven analytics, and allocation of resources achieved through public and private partnerships. Global approaches to public health problems will become standard.

The rapid and profound rise of global commerce and trade requires that FDA continue to evolve and meet new demands—the demands of global approaches to public health problems have become inherent in FDA’s daily work and long-term strategy. FDA has significantly strengthened its ability to respond to these challenges and know where and how it must do more in its mission of protecting and promoting the health of the American public.

NOTES

1. The FDA Modernization Act (FDAMA) of 1997 granted FDA authority to “participate through appropriate processes with representatives of other countries to reduce the burden of regulation, harmonize regulatory requirements, and achieve appropriate reciprocal arrangements.” (21 USC § 393(b)(3), added by Pub. L. No. 105-115, 111 Stat. 2369, § 406). This language recognized and mandated FDA’s participation in harmonization efforts, such as the International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH).

REFERENCES

Preston, Charles et al. 2013. “Developing a Global Curriculum for Regulators.” Institute of Medicine of the National Academies (June 11).