Matthews Hill, between River Bull Run and the Warrenton Turnpike, declines southwards to a small tributary stream called Young’s Branch, which presented no obstacle to advancing soldiers. Beyond the stream the ground rises gently, mostly through woodland, to the Warrenton Turnpike that crossed the Northern line of advance from East to West. Beyond the turnpike rise the steeper slopes of Henry Hill, dotted with trees but with much open grassland as well. It is not a particularly steep incline, but it gains height steadily for some 800 yards to reach a wide, undulating plateau with woodland on its farther side. It was here that the key encounter of the First Battle of Bull Run was to take place, a long and fierce and fluctuating struggle.

In July 1861 there were two modest houses on this hillside. A hundred yards above the turnpike, at the top of a grassy lane with split-rail fencing on each side, stood Robinson’s House, the clap-board cottage of a freed slave. Almost at the top of the hill, just where it begins to level out to the summit plateau, there was a slightly grander place called Henry House. This had been the farm and family home of the man who gave his name to the hill, Dr. Isaac Henry, a retired naval surgeon. By 1861 he had been long dead, but his widow, Judith, a helpless invalid of 84, and two of their sons who were both semi-invalids, were still there, being looked after by a young Negress called Rosa Stokes. They were all in the house as the Northern army approached.

The advance of McDowell’s line towards Henry Hill brought the sounds of battle closer to the two Southern commanders, Johnston and Beauregard. They were stationed at the centre of their line, on a small hill just south of Mitchell’s Ford and nearly two miles to the south-east of Henry Hill. From Beauregard’s point of view this was the proper place to be. He expected McDowell’s main attack in this area and planned to launch his own assault, towards Centreville, with the brigades on his immediate right.

Henry House as seen from the back of the Robinson House.

Unfortunately, nothing seemed to be happening as he had expected. Soon after first light the enemy had appeared on the slopes beyond Mitchell’s Ford, but since then, bewilderingly, he had made no strenuous effort to press ahead with his advance. At the same time, Beauregard’s own orders for a push across Bull Run by the brigades on the right wing of his line – Longstreet’s at Blackburn’s Ford, Jones’s at McLean’s Ford and Ewell’s (with Holmes’s in support) at the railway crossing – were clearly not being implemented. In fact, Longstreet and Jones had moved their forward units across the river and formed them into line; then they waited for Ewell to join them on their right. He did not arrive. Beauregard’s courier had never reached Brigadier General Ewell with the orders. The courier dispatched to Brigadier General Holmes also failed to deliver. Since no one on Beauregard’s staff had noted the couriers’ names, these failures in communication were never explained. So both generals held their positions and waited, with mounting and ill-concealed impatience. Ewell especially, 44 years old and desperately eager for action, made no secret of his feelings. Finally he got orders to advance, moved fast across the river, and then got orders to pull back again and resume a defensive position. By the end of the day, it was reckoned, Ewell’s Brigade had marched and countermarched more than twenty miles in the heat of the day without once coming to grips with the enemy. Holmes’s Brigade, too, saw no action.

The lane, with split-rail fencing either side, that leads from the Warrenton Turnpike to Robinson’s House. It was here that Colonel Wade Hampton made the gallant and successful stand that further delayed the Northern advance.

A private of the 1st Virginia Cavalry, the riders who distinguished themselves before and during (and long after) First Bull Run, under the command of Colonel ‘Jeb’ Stuart. Far right, a private of the 23rd Virginia Regiment. (Illustration by Michael Youens)

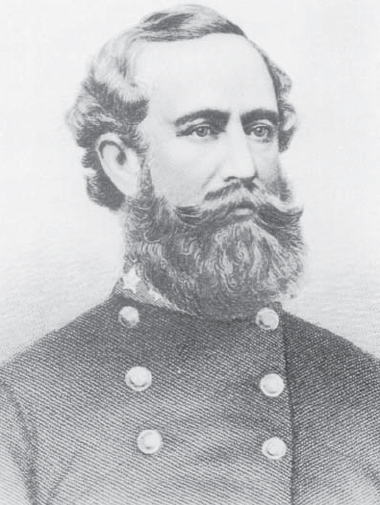

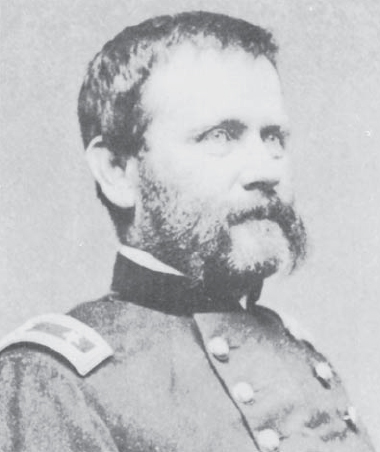

Brigadier General Richard S. Ewell, commanding Beauregard’s 2nd Brigade, was desperately keen to get into the fight and was continually frustrated. It was intended that he should be part of the drive on Centreville, but – through administrative incompetence – Beauregard’s orders never reached him. Like the Grand Old Duke of York, Ewell marched his men up and down all that hot summer’s day and never got anywhere. (Anne S. K. Brown Mil. Coll., BUL)

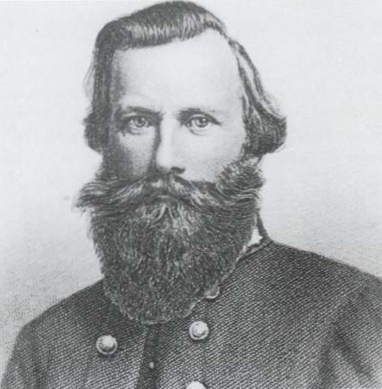

Wade Hampton was outstanding even in an era of remarkable men. Some said he was the greatest landowner in the South. In the South Carolina state legislature he spoke out for secession. And when the Civil War came he threw everything – his fortune and his considerable energies – into raising and training his own Legion. He took 650 men to Bull Run. They only just arrived, in time, by railway from the South, but played an important part in holding up the North’s attack on Henry Hill until Jackson had organized his defensive line on the summit plateau. (Anne S. K. Brown Mil. Coll., BUL)

Johnston and Beauregard grew more and more concerned as the morning wore on and, while little was happening in front of them or to the right, a great deal was clearly going on to their left. Sometime between 11 a.m. and noon, the Signal Officer, Captain Alexander, reported that he had seen a great cloud of dust in the sky to the northwest. The two generals were afraid this marked the approach of General Patterson from the Shenandoah. At last Johnston determined to take matters into his own hands.’ The battle is there,’ he said to Beauregard, pointing to the left. ‘I am going.’ He rode off.

Beauregard issued rapid orders. The brigades of Holmes, Early and Bonham should move, with speed, towards the sound of battle. Those of Longstreet, Jones and Ewell should resume their defensive positions south of Bull Run. Then Beauregard too galloped towards Henry Hill.

The situation on their left flank looked desperate. Evans, Bee and Bartow had been driven back from Matthews Hill in considerable disorder. For the North, reinforcements were arriving in strength. McDowell and his brigade commanders worked hard to form them into line for what they hoped would be the final big push to victory. Sherman was posted by the Sudley Springs road; what was left of Burnside’s brigade was on his left; Keyes’s brigade to the left of them. To the right of Sherman, Porter re-grouped his men. Two of Heintzelman’s brigades, those of Colonel W. B. Franklin and Colonel O. B. Willcox, were directed to extend the right flank as they came up. It was a formidable force.

The South also had reinforcements on the way, but for the moment the only new men in the field were the 650 infantryman from South Carolina of Colonel Wade Hampton’s Legion. The colonel, one of the great landowner/planters of the South, was an immensely wealthy and charismatic man. He was patriotic too for the Confederacy. The Legion was his own, raised and financed and led by him. Theirs had been an eventful day already. Shortly after first light their train from Richmond had pulled into Manassas Junction. They had made a quick breakfast and then orders came to hurry to the relief of Evans on the extreme left flank. It was a three-hour cross-country march and much had happened before they reached the summit of Henry Hill. They arrived just in time to see their own forces falling back and the enemy preparing to advance in line. Colonel Hampton led the way rapidly down the hill to the area of Robinson’s House. They took position and almost immediately found themselves attacked from three sides by vastly superior numbers. They held their ground stoutly and had time to fire several volleys before they were forced to retreat back up Henry Hill. It was a purely holding operation, but a successful one. It gave time for another new arrival to take position – General T. J. Jackson.

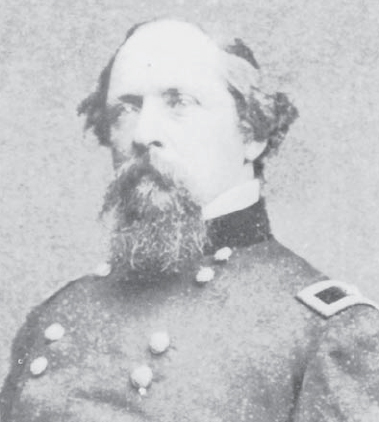

It was shortly before noon when General Jackson arrived at the summit of Henry Hill with his 2,000 Virginians. He rapidly grasped the situation and organized his men into a superb defensive position, so good that the attacking Northern regiments were unable to break through and, in the end, wore themselves out in their repeated attempts. (Anne S. K. Brown Mil. Coll., BUL)

Jackson’s Brigade – just over 2,000 Virginians with four cannon – had started the day before dawn. First they were moved forward to support Long-street; later they were ordered two miles to the left to support Bonham and Cocke. When he arrived there, Jackson heard the din of the real battle going on even farther to the left and, as Bee and Bartow had done before him, immediately pressed on. He emerged from the woods on to the summit plateau of Henry Hill at about 11.30 a.m.

At that moment there was a brief lull in the fighting, both sides hurriedly re-forming their lines. Many of Bee’s men – some of them wounded, others shattered by their first experience of battle – were stumbling through to the rear, speaking of defeat. As one of the Jackson’s men said, it ‘was not an encouraging sight to brand-new troops’.

Jackson organized his brigade into line, 150 yards or so behind the forward crest of the hill. It was an excellent position, of the type often used and recommended by the Duke of Wellington. The woods immediately behind offered good cover. The men would be invisible to the enemy guns and invisible to their infantry too until the moment when they emerged on to the plateau, within close range. In the centre of his line Jackson placed one of his own batteries and the four smooth-bore six-pounders of Captain John Imboden that had been busily pounding the enemy at the foot of the hill.

Before long they heard the battle resume. Then, to their right, they saw Bee’s men in flight. To give some cover to Wade Hampton’s beleagured Legion, Jackson got his guns firing.

The infantrymen on the right of the line, lying on the grass and waiting, saw a single horseman galloping towards them. One of them described the moment: ‘He was an officer all alone, and as he came closer, erect and full of fire, his jet-black and long hair, and his blue uniform of a general officer made him the cynosure of all.’ It was General Bee. He asked who their commander was, then rode along the line. An orderly sergeant of Jackson’s, Henry Kyd Douglas, later wrote: ‘General Jackson was sitting on his horse very near us. General Bee, his brigade being crushed, rode up to him and with the mortification of an heroic soldier reported that the enemy was beating him back.

“Very well, General,” replied Jackson.

“But how do you expect to stop them?”

“We’ll give them the bayonet,” was the brief answer.

Bee galloped away and General Jackson turned to Lieutenant H. H. Lee of his staff with this message:

“Tell the colonels of this brigade that the enemy are advancing; when their heads are seen above the hill, let the whole line rise, move forward with a shout and trust to the bayonet. I’m tired of this long-range work!”’

Bee rode off to see what was left of his brigade. He could only find one of his regiments, the 4th Alabama, and they were disorganized and dispirited, all their senior officers gone. Bee appealed to them to return to the fighting under his command. It is not certain what his exact words were. The first published account appeared in The Charleston Mercury, quoting General Bee’s principal aide. According to this, Bee turned to the Alabamans, gestured with his sword towards Jackson’s line and shouted: ‘There is Jackson standing like a stone wall. Let us determine to die here, and we will conquer. Follow me!’ Beauregard, in his account of the battle, gives the words that are usually quoted: ‘Look! There stands Jackson like a stone wall. Rally behind the Virginians!’ Three days after the battle, back in Richmond, one of Beauregard’s staff officers, Colonel Chesnut, was reunited with his wife and told her, and she wrote it into her diary, of ‘Colonel Jackson, whose regiment stood so stock still under fire that they are called a stone wall’. Whatever the precise wording and circumstance, an enduring and legendary name had been given. And Bee’s call worked. The men of the 4th Alabama followed him back towards the enemy. Bee, still on horseback, was at the head of the leading company when they came under fierce fire from the Northern artillery. Bee was severely wounded, and an aide carried him to the rear. He died before the day was out.

It was about this time, half an hour into the afternoon, that the commanding generals, Johnston and Beauregard, finally arrived at the summit of Henry Hill. For the first time that day they were under heavy fire, but they calmly disregarded it and set about reorganizing their shattered units and getting them back into a defensive line around Jackson. Beauregard wrote: ‘We found the commanders resolutely stemming the further flight of the routed forces, but vainly endeavouring to restore order, and our own efforts were as futile. Every segment of line we succeeded in forming was again dissolved while another was being formed: more than two thousand men were shouting each some suggestion to his neighbour, their voices mingling with the noise of the shells hurtling through the trees overhead, and all word of command drowned in the confusion and uproar. The disorder seemed irretrievable, but happily the thought came to me that if their colours were planted out to the front the men might rally on them, and I gave the order to carry the standards forward some 40 yards which was promptly executed by the regimental officers, thus drawing the common eye of the troops. They now received easily the orders to advance and form on the line of their colours, which they obeyed with a general movement; and as General Johnston and myself rode forward shortly after with the colours of the 4th Alabama by our side, the line that had fought all morning, and had fled, routed and disordered, now advanced again into position as steadily as veterans.’

Johnston’s account of the same incident is less colourful but almost certainly more reliable: ‘When we were near the ground where Bee was re-forming and Jackson deploying his brigade, I saw a regiment in line with ordered arms and facing to the front, but 200 or 300 yards in rear of its proper place. On inquiry I learned that it had lost all its field officers; so, riding on its left flank, easily marched it to its place. It was the 4th Alabama, an excellent regiment, and I mention this because the circumstance has been greatly exaggerated.’

In their subsequent accounts the two generals also gave rather different versions of a vital issue that now arose. Beauregard wrote: ‘As soon as order was restored I requested General Johnston to go back to Portici (the Lewis house) and from that point – which I considered most favourable for the purpose – forward me the reinforcements as they would come from the Bull Run lines below and those that were expected to arrive from Manassas, while I should direct the field. General Johnston was disinclined to leave the battle-field for that position . . . I felt it was a necessity that one of us should go to this duty, and that it was his place to do so, as I felt responsible for the battle. He considerately yielded to my urgency. . .’

Johnston’s description of this conversation agrees that the suggestion came from Beauregard and that he accepted it, but makes it firmly clear that he retained command of the whole battlefield: ‘I gave every order of importance,’ he said.

The incident reveals their contrasting characters. Johnston was insisting that it was he who was in charge of the battle. Beauregard was claiming that, once he had arrived on the scene, the key action of the day was his. In effect, however, the division of duties was both sensible and successful. Johnston rode the mile or so back to the Portici, which gave him a wide view of most of the field of action, a more central position and readier access to the other brigades. Those that were being hurried towards Henry Hill had to pass close by the Portici, and Johnston was able to give them precise directions. Beauregard, meanwhile, was in his element – in the heat of the action, riding along the lines to shout words of praise and encouragement as the vision of glory inspired him. The men cheered him as he passed. A bursting shell killed his horse under him. General Bartow, rallying the men of his 8th Georgia Regiment and putting them in position on Jackson’s left, fell with a bullet through his heart. ‘With 6,500 men and 13 pieces of artillery’, Beauregard wrote, ‘I now awaited the onset of the enemy, who were pressing forward 20,000 strong, with 24 pieces of superior artillery and seven companies of regular cavalry.’

Beauregard was exaggerating the disparity in strengths and, in the interest of promoting his heroic image, made no mention of the very real advantages he enjoyed. There had been time to organize his line; his men were in the defensive role; the enemy had to attack uphill, across mostly open ground. And now he had ‘Jeb’ Stuart and his cavalrymen, who had ridden hard from the Shenandoah to be in time for the fight and had now been placed on the left of Jackson’s line.

In fact, though it was not realized until much later, the Northern commander, McDowell, had already missed the best chance he was to get that day. He had imposed his plan upon the battle. He had succeeded in getting more infantrymen and more guns to the vital place than the enemy had. Then, unaccountably, he had delayed his attack. And when he did attack, it was piecemeal. He had whole brigades available to him but he launched his men up the hill by the regiment only. One by one the regiments advanced, to be pounded by the enemy artillery as they struggled up the hill, then, as they emerged on to the plateau, to be met by a tremendous volley of fire from the infantry at short range. They would be driven back and, after a pause, giving the enemy time to reload, another regiment would be hurled forward to meet the same reception. Jackson had no need to order his threatened bayonet charge. They simply had to maintain their position, fire and re-load. He was a calming, reassuring influence, moving along the line and saying, ‘Steady, men! Steady! All’s well!’

Early on in the Henry Hill engagement, McDowell made a serious tactical error. He ordered two of his best batteries, those of Charles Griffin and J. B. Ricketts, to advance to a position near to the Henry House, from which they could batter the Southern line at close range. These were batteries of the regular US army, efficient and ably commanded. From the very beginning of the battle they had been actively engaged, directing their fire at Evans’s Brigade on Matthews Hill, then advancing on to that hill to hit the enemy positions on Henry Hill. Griffin had had one of his guns disabled, but Captain James Ricketts’s battery was intact – six ten-pounder rifled guns.

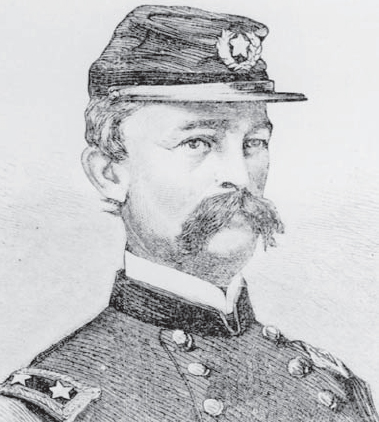

The irrepressible ‘Jeb’ Stuart, who led the only effective cavalry unit involved in the battle, turned up on the left of Jackson’s line; charged and dispersed the 11th New York Regiment; and later told Jubal Early that if he attacked now the enemy might well break, which is exactly what happened. (Anne S. K. Brown Mil. Coll., BUL)

This drawing by W. Momberger gives a spirited impression of the scene on the lower slopes of Henry Hill during the long afternoon, as one by one the Northern regiments marched up the hill in an attempt to break Jackson’s line. (Anne S. K. Brown Mil. Coll., BUL)

When they got the order to advance, the two captains asked what infantry support they would have. They were told that the 11th New York Regiment, the Zouaves, were on their way at the double. They were dubious, but the order was firm, so they dutifully limbered their guns and set off.

The Southern battery commander John Imboden could hardly believe what he saw from the top of Henry Hill. There had been a lull in the action. ‘My men lay about’, Imboden wrote, ‘exhausted from want of water and food, and black with powder, smoke and dust.’ Then he saw the enemy batteries advancing, unaccompanied: ‘It was at this time that McDowell committed, as I think, the fatal blunder of the day, by ordering both Ricketts’s and Griffin’s batteries to cease firing and move across the turnpike to the top of the Henry Hill, and take positions on the west side of the house. The short time required to effect the change enabled Beauregard to arrange his new line of battle on the highest crest of the hill . . . If one of the Federal batteries had been left North of Young’s Branch, it could have so swept the hilltop where we re-formed, that it would have greatly delayed, if not wholly have prevented, us from occupying the position.’

Ricketts was first up the hill, but as he approached Henry House he came under fire from sharpshooters. ‘I turned my guns upon the house’, he said, ‘and literally riddled it.’ One of the shots smashed the bed on which the widow Henry was lying. She died a few hours later, the only woman casualty of the battle. Soon after – it was now about 2 p.m. – Griffin’s battery arrived, and they turned their combined fire on Jackson’s line, only 200 yards away.

But the batteries were completely unprotected. The 11th New York Regiment, in their bright red Zouave trousers, moved up the hill, at the double, to support them. The Southerners held their fire until the Zouaves were on the plateau, then let them have a thunderous volley. It was frightening rather than anything else. One Virginian witness commented wryly on his comrades’ marksmanship: ‘I recollect their first volley. It was apparently made with guns raised at an angle of 45 degrees, and I was fully assured that the bullets would not hit the Yankees, unless they were nearer heaven than they were generally located by our people.’ After that, however, the Southerners’ shooting improved, and the Zouaves found themselves pinned down in a hail of fire. The two companies on their right pulled back down the hill, escaping the rifle fire but running into ‘Jeb’ Stuart’s cavalrymen who charged among them, slashing with sabres and firing their carbines. The plateau and slopes of Henry Hill had become an inferno of fire, smoke and confusion.

Captain Charles Griffin commanded the battery of the 5th US Artillery. They were in action early, against Evans on Matthews Hill. Later, when McDowell ordered two batteries to take position near Henry House, Griffin made no secret of his doubts about the move but obeyed the order. The result was disaster. (Anne S. K. Brown Mil. Coll., BUL)

Captain Imboden, firing shrapnel at the advancing Northerners, forgot to step away from the gun’s muzzle: ‘Heavens! what a report. Finding myself full 20 feet away, I thought the gun had burst. But it was only the pent-up gas, that, escaping sideways as the shot cleared the muzzle, had struck my side and head with great violence. I recovered in time to see the shell explode in the enemy’s ranks. The blood gushed out of my left ear, and from that day to this it has been totally deaf.’

Captain James Ricketts, commander of the 1st US Artillery, went up Henry Hill ahead of Griffin and drove the enemy out of Henry House. When the batteries were overrun he was wounded and captured. He recovered, was released, became a brigadier general and took part – as did many of the officers on the field at First Bull Run – in the Second Battle of Bull Run in August 1862. (Anne S. K. Brown Mil. Coll., BUL)

Another of Frank Vizetelli’s sketches for the Illustrated London News. It was captioned: ‘Attack on the Confederate batteries at Bull Run by the 27th and 14th New York Regiments – from a sketch by our special artist’. (Illustrated London News)

The fight for the guns of the two Federal batteries at Henry House became a popular subject for American artists. This was a painting by E. Jahn. (Anne S. K. Brown Mil. Coll., BUL)

Imboden’s battery had run out of ammunition. He ran to Jackson to ask permission to retire: ‘The fight was just then hot enough to make him feel well. His eyes fairly blazed. He had a way of throwing up his left hand with the open palm toward the person he was addressing. And as he told me to go, he made this gesture. The air was full of flying missiles, and as he spoke he jerked down his hand and I saw the blood was streaming from it. I exclaimed, “General, you are wounded.” He replied, as he drew a handkerchief from his breast pocket, and began to bind it up, "Only a scratch – a mere scratch," and galloped away along his line.’

Jackson was enjoying himself, getting cooler as the fighting grew hotter. The Northerners were still attacking in waves, and there were moments when it looked as though they would break through. An officer rode up to Jackson and said, ‘General, the day is going against us.’ ‘If you think so, sir,’ Jackson replied, ‘you had better not say anything about it.’

A further case of mistaken identity did much to help the Southern cause. Colonel Arthur C. Cummings’s 33rd Virginia Regiment wore blue uniforms. The Colonel, afraid that his men would break and run if they were held in position any longer, ordered them to advance towards the guns of Ricketts and Griffin. Griffin saw them coming and swung two of his guns round and had them loaded with canister. Just as he was about to fire, his superior officer, Major William F. Barry, shouted, ‘Captain, don’t fire there; those are your battery support.’ ‘They are Confederates’, Griffin shouted back, ‘as certain as the world, they are Confederates.’ But Barry insisted, and the guns were swung back to their original line of fire. The Virginians, meanwhile, marched ever closer, in line; then halted, raised their rifles and fired a volley. ‘And that’, Griffin told a subsequent Board of Inquiry, ‘was the last of us. We were all cut down.’ Most of their horses and many of the gunners were killed. Ricketts was severely wounded. Griffin struggled to save what he could, but Cummings and his Virginians were among them quickly to capture ten field guns and much ammunition.

Brigadier General William B. Franklin, commander of the 1st Brigade of Heintzelman’s Division, had a distinguished army career: first in his class at West Point, promoted in the Mexican War, an accomplished surveyor and engineer. At Bull Run his men, from Minnesota and Massachusetts, did not reach the front until the struggle for Matthews Hill was over, but after that they were continuously under fire throughout the struggle on Henry Hill. (Anne S. K. Brown Mil. Coll., BUL)

McDowell was not prepared to abandon such a prize. Two regiments of Franklin’s brigade, men from Massachusetts who had just reached the scene after a long march, were sent charging up the slope. They re-took the guns, but only briefly, before being driven back by Jackson and his Virginians – Beauregard with them, shouting, ‘Give them the bayonet! Give it to them freely!’ When the enemy fell back, he rode along his line, crying, ‘The day is ours.’ Moments later Heintzelman, the commander of McDowell’s Third Division, led the 1st Minnesota Regiment in a counter-attack, and the Virginians were driven back yet again.

The battle swayed to and fro. Another of Heintzelman’s brigade commanders, Brigadier General Orlando Bolivar Willcox, led his own regiment, the 1st Michigan, up the hill to retake the guns. Then Jackson charged and drove them down again. Willcox’s men were to be in the thick of the action from now on. But Willcox himself was quickly wounded and then captured. He ran towards a line of men in blue uniforms to tell them they were firing on friends, discovering too late that they were the enemy.

So it went on for nearly two hours, at the hottest time of a very hot day – a brutal, interminable slogging-match, devoid of military finesse. The premium was on courage and endurance. Even Jackson was impressed: ‘It was the hardest battle I have ever been in,’ he said a few days later.

Sherman’s brigade was heavily involved and his official report written four days later; gives a vivid impression of what it was like: ‘This regiment [the 2nd Wisconsin] ascended to the brow of the hill steadily, received the severe fire of the enemy, returned it with spirit, and advanced, delivering its fire. This regiment is uniformed in grey cloth, almost identical with that of the great bulk of the secession army; and, when the regiment fell into confusion and retreated toward the road, there was a universal cry that they were being fired on by our own men. The regiment rallied again, passed the brow of the hill a second time, and was again repulsed in disorder. By this time the New York 79th had closed up, and in like manner it was ordered to cross the brow of the hill and drive the enemy from cover. It was impossible to get a good view of this ground. . . . The fire of rifles and musketry was very severe. The 79th, headed by its colonel, Cameron, charged across the hill, and for a short time the contest was severe; they rallied several times under fire, but finally broke . . . This left the field open to the New York 69th, Colonel Corcoran, who, in his turn, led his regiment over the crest, and had in full, open view the ground so severely contested; the fire was very severe, and the roar of cannon, musketry and rifles, incessant; it was manifest the enemy was here in great force, far superior to us at that point. The 69th held the ground for some time, but finally fell back in disorder.’

The commander of the New York 79th, Colonel James Cameron (his brother was President Lincoln’s Secretary of War) was killed in this action. A few days later, describing the action in a letter to his wife, Sherman said, ‘I do think it was impossible to stand long in that fire.’ One Southern officer turned to a friend and said, ‘Them Yankees are just marchin’ up and bein’ shot to hell.’ The key factor in all this was the admirable defensive line that Jackson had chosen when he first arrived: set back from the rim of the plateau, semi-circular in shape, allowing converging fire from various directions; backed by woodland that gave the defenders good cover.

It is hard, at least with the benefit of hindsight, to see why intelligent commanders like McDowell and Sherman persisted so long with their costly, piecemeal, frontal attacks. Sherman would not have done so later on in his fighting career. McDowell had the resources, initially, to mount a frontal assault in brigade strength – one wave of men following the other too quickly to allow the enemy time to reload and reorganize. Or he could have sent Heintzelman’s fresh brigades farther round the western flank to attack the enemy’s side and rear. Either of these tactics, or both applied simultaneously, would almost certainly have won him the day. But none of these options was tried. The men had not been drilled in large-formation movements. Their commanders had never handled units of this size before. McDowell simply went on hoping that his next regimental attack would bring the breakthrough.

And he was, in effect, on a diminishing spiral. His new regiments, moving up to the front, could see what was happening to their predecessors. They marched past many wounded or demoralized men, scurrying to find safety. The morale impact was powerful. It is a tribute to the calibre of these young, untried, volunteer soldiers that so many of them went on fighting for so long. But all the time, the North was losing men and confidence.

Another artist’s impression of the scene at the height of the struggle. It depicts Colonel Michael Corcoran leading a charge of the 69th Regiment against Southern batteries. (Anne S. K. Brown Mil. Coll., BUL)

About 3 p.m. the last of Heintzelman’s brigades arrived – Howard with three regiments from Maine and one from Vermont. They were hurled into the attack, then hurled back by the enemy. McDowell had no more reinforcements on the way.

For Beauregard, on the other hand, things were very different. General Johnston was feeding him with a constant stream of support – Virginian regiments from Cocke’s Brigade, two of Bonham’s South Carolina regiments. Some were used to strengthen Jackson’s line. Others were sent to extend his western flank. And there were more on the way.

The tide of the battle was turning.