Chapter 1

The Business Case for Decision Assurance and Information Security

Why do businesses, governments, the military, or private individuals need to have “secure” information? As an SSCP, you'll have to help people and organizations identify their information security needs, build the systems to secure their information, and keep that information secure.

We'll focus your attention in this chapter on how businesses use information to get work done—and why that drives their needs for information security. In doing so, you'll see that today's global marketplaces present a far more challenging set of information security needs than even a country's government might.

To see how that all works, you'll first have to understand some fundamental concepts about information, business, governance, and security.

Information: The Lifeblood of Business

Human beings are first and foremost information processing animals. We sense the world around us and inside us; we translate those sensory signals into information that our mind uses as we make decisions. We use our memories of experiences as the basis of the new thoughts that we think, and we use those thoughts as we decide what goals to strive for or which actions to take right in this immediate moment. Whether we think about a pretty sunset or a bad business decision, we are using information. All living things do this; this is not something unique to humans! And the most fundamental way in which we use information is when we look at some new thing our senses report to us and quickly decide: is it food, is it friend, is it foe, or can it be safely ignored? We stay alive because we can make that decision quickly, reliably, and repeatedly.

We also enhance our survival by learning from experience. We saw something new yesterday, and since it didn't seem to be friend or foe, we tasted a bit of it. We're still alive today, so it wasn't poisonous to us; when we see it today, we recognize it and remember our trial tasting. We have now learned a new, safe food. As we continue to gather information, we feed that new information back into our memory and our decision-making systems, as a way of continuing to learn from experience.

We also help others in their learning by making our knowledge and experience something that they can learn from. Whether we do that by modeling the right behaviors or by telling the learner directly, we communicate our knowledge and experience—we transfer information to achieve a purpose. We invented languages that gave us commonly understood ways of communicating meaning, and we had to develop ways we could agree with one another about how to carry on a conversation.

We use language and communication, loaded with information and meaning, to try to transform the behavior of others around us. We advise or guide others in their own decision making; in some situations, we can command them to do what we need or want. Each of these situations requires that we've previously worked to set the conditions so that transferring the information will lead to the effects we want. What conditions? Think of all of the things you implicitly agree to when having a conversation with someone:

- Understanding and using the same language, and using the same words and gestures for the same meanings

- Using the same rules to conduct the conversation—taking turns, alternating “sending” and “receiving”

- Signaling that the message was understood, or that it was not understood

- Signaling agreement

- Seeking additional information, either for greater understanding or to correct errors

- Agreeing to ways to terminate the conversation

Information systems builders refer to such “rules of the road” as the protocols by which the system operates. As humans, we've been using protocols since we learned to communicate. And as people band together in groups—families, clans, societies, businesses—those groups start with the person-to-person communications methods and languages, and then layer on their own protocols and systems to meet their special needs. It is our use of information that binds our societies together (and sometimes is used to tear them apart!).

Data, Information, Knowledge, Wisdom…

In casual conversation, we recognize that these terms have some kind of hierarchical relationship, and yet we often use them as if they are interchangeable names for similar sets of ideas. In knowledge management, we show how each is subtly different and how by applying layers of processing and thought, we attain greater value from each layer of the knowledge pyramid (shown in Figure 1.1):

- We start with data—the symbols and representations of observable facts, or the results of performing measurements and estimates. Your name and personally identifiable information (PII) are data elements, which consist of many different data items (your first, middle, and surnames). Raw data refers to observations that come directly from some kind of sensor, recorder, or measuring device (a thermometer measures temperatures, and those measurements are the raw data). Processed data typically has had compensations applied to it, to take out biases or calibration errors that we know are part of the sensor's original (raw) measurement process.

- We create information from data when we make conclusions or draw logical inferences about that data. We do this by combining it with the results of previously made decisions, or with other data that we've collected. One example might be that we conclude that based on your PII, you are who you claim to be, or by contrast, that your PII does not uniquely separate you from a number of other people with the same name, leading us to conclude that perhaps we need more data or a better process for evaluating PII.

- We generate knowledge from data and information when we see that broad general ideas (or hypotheses) are probably true and correct based on that data and information. One set of observations by itself might suggest that there are valuable mineral or oil and gas deposits in an area. But we'll need a lot more understanding of that area's geography before we decide to dig a mine or drill for oil!

- Wisdom is knowledge that enables us to come to powerful, broad, general conclusions about future courses of action. Typically, we think of wisdom as drawing on the knowledge of many different fields of activity, and drawing from many different experiences within each field. This level of the knowledge pyramid is also sometimes referred to as insight.

FIGURE 1.1 The knowledge pyramid

Obviously, there's a lot of room for interpretation as to whether some collection of facts, figures, ideas, or wild guesses represents “data” in its lowest form, “wisdom” in its most valuable, or any level in between on that pyramid. Several things are important for the SSCP to note as we talk about all of this:

- Each step of processing adds value to the data or information we feed into it. The results should be more valuable to the organization, the business, or the individual than the inputs alone were. This value results from the combination with other information, and from applying logic and reasoning to create new ideas.

- The value of any set of inputs, and the results of processing them, is directly in proportion to their reliability. If the data and the processing steps are not reliable, we cannot count on them as inputs to subsequent processing. If we do use them, we use them at risk of being misled or of making some other kind of mistake.

- From data to wisdom, this information can be either tacit (inside people's heads) or explicit (in some form that can be recorded, shared, and easily and reliably communicated).

Although we often see one label (such as “data”) used for everything we do as we observe, think, and decide, some important distinctions must be kept in mind:

- Data should be verifiable by making other observations: either repeat the observations of the same subject, or make comparable observations of other subjects.

- Data processing tends to refer to applying logic and reasoning to make sure that all of the observations conform to an acceptable quality and consistency standard. This is sometimes called data cleaning (to remove errors and biases), data validation (to compare it to a known, accepted, and authoritative source), or data smoothing (to remove data samples that are so “out of range” that they indicate a mistaken observation and should not be used in further processing). Manually generated employee time card information, for example, might contain errors—the most common is having the wrong year written down for the first pay period after the New Year!

- Information processing usually is the first step in a series of actions where we apply business logic to the data to inform or enable the next step in a business process. Generating employee payroll from the time cards might require validating that the employee is correctly identified and that the dates and hours agree with the defined pay period, and then applying the right pay formula to those hours to calculate gross pay earned for that period.

As an SSCP, you may also encounter knowledge management activities in your business or organization. Many times, the real “know-how” of an organization exists solely inside the minds of the people who work there. Knowledge management tries to uncover all of that tacit knowledge and make it into forms that more people in the company can learn and apply to their own jobs. This is an exciting application of these basic ideas and can touch on almost every aspect of how the company keeps its information safe and secure. It is beyond the scope of the SSCP certification exam, but you do need to be aware of the basic idea of knowledge management.

Information Is Not Information Technology

As an SSCP you will regularly have to distinguish between the information you are protecting and the technologies used to acquire, process, store, use, and dispose of that information. As discussed, information is about things that people or businesses can know or learn. If that information is written on paper documents, then the pencils or pens and the paper are how that information is captured and communicated; filing cabinets become the storage technology. The postal system or a courier service becomes part of the communications processes used by that business. Look around almost any modern-day business or organization, and you see a host of information technologies in use:

- Computers and networks to connect them, and disks, thumb drives, or cloud service providers for storage and access

- Paper documents, forms to fill out, and a filing cabinet to put them in

- Printed, bound books, and the bookshelves or library spaces to keep them in

- Signs, posters, and bulletin boards

- Audio and acoustic systems, to convey voice, music, alarms, or other sounds as signals

- Furniture, office, and workspace arrangement, and the way people can or are encouraged to move and flow through the workspaces

- Organizational codes and standards for appearance, dress, and behavior

These and many more are ways in which meaning is partially transformed into symbols (text or graphics, objects, shapes or colors), the symbols arranged in messages, and the messages used to support decision making, learning, and action. Figure 1.2 demonstrates many of these different forms that information may take, in a context that many of us are all too familiar with: passenger security screening at a commercial airport.

FIGURE 1.2 Messaging at passenger screening (notional)

As an SSCP, you need to know and understand how your organization uses information and how it uses many different technologies to enable it. As an SSCP, you protect the information as well as the technologies that make it useful and available.

Notice how many different types of technologies are involved—and yet, “IT” as the acronym for “information technology” only seems to refer to digital, general-purpose computers and the networks, communications, peripherals, software, and other devices that make them become an “information processing system.”

In the introduction, we defined the first S in SSCP to mean information systems. After all, an SSCP is not expected to keep the air conditioning systems in the building working correctly, even though they are a “system” in their own right. That said, note that nothing in your job description as an SSCP says “I only worry about the computer stuff.”

Policy, Procedure, and Process: How Business Gets Business Done

As an SSCP, you might be working for a business; you might even open your own business as an information security services provider. Whatever your situation, you'll need to understand some of the basic ideas about what business is, how businesses organize and govern themselves and their activities, and what some of the “business-speak” is all about. Some of this terminology, and some of these concepts, may occur in scenarios or questions you'll encounter on the SSCP exam, but don't panic—you're not going to need to get a business degree first before you take that exam!

Let's get better acquainted with business by learning about the common ways in which businesses plan their activities, carry them out, and measure their success. We'll also take a brief look at how businesses make decisions.

Who Is the Business?

As an SSCP, you will most likely be working for a business, or you will create your own business by becoming an independent consultant. Either way, “know your client” suggests that you'll need to know a bit about the “entity” that is the business that's paying your bills. Knowing this can help you better understand the business's decision processes, as you help them keep those processes and the information they depend on secure.

Businesses can in general take on several legal forms:

- A sole proprietorship is a business owned by one person, typically without a legal structure or framework. Usually the business operates in the name of that individual, and the bank accounts, licenses, leases, and contracts that the business executes are in the individual owner's name. One-person consulting practices, for example, and many startup businesses are run this way. When the owner dies, the business dies.

- A corporation is a fictitious entity—there are no living, breathing corporations, but they exist in law and have some or all of the civil and legal rights and responsibilities that people do. The oldest business still operating in the world is Hōshi Ryokan in Komatsu, Japan, which has been in business continually since the year 705 AD. In the United States, CIGNA Insurance, founded in 1792, is one of the four oldest corporations in America (three others were also formed the same year: Farmer's Almanac, the New York Stock Exchange, and the law firm of Cadwalader, Wickersham & Taft). Corporations can take many forms under many legal systems, but in general, they have a common need for a written charter, a board of directors, and executive officers who direct the day-to-day operation of the company.

- A partnership is another form of fictitious, legal entity that is formed by other legal entities (real or fictitious) known as the general partners. The partners agree to the terms and conditions by which the partnership will operate, and how it will be directed, managed, and held accountable to the partners.

Businesses also have several sets of people or organizations that have interest in the business and its successful, safe, and profitable operation:

- Investors provide the money or other assets that the business uses to begin operations, expand the business, and pay its expenses until the revenues it generates exceed its expenses and its debt obligations. The business uses investors’ money to pay the costs of those activities, and then pays investors a dividend (rather like a rent payment), much as you'd pay interest on a loan. Unlike a lender, investors are partial owners in the business.

- Stakeholders are people or organizations that have some other interest or involvement with the business. Neighboring property owners are stakeholders to the extent that the conduct of this business might affect the value of their properties or the income they generate from their own businesses. Residential neighbors have concerns about having a peaceful, safe, and clean neighborhood. Suppliers or customers who build sizable, enduring, or otherwise strategic relationships with a business are also holding a stake in that business's success, even if they are not investors in it.

- Employees are stakeholders too, as they grow to depend on their earnings from their jobs as being a regular part of making their own living expenses.

- Customers will grow to depend on the quality, cost-effectiveness, and utility of what they buy from the business, and to some extent enjoy how they are treated as customers by the business.

- Competitors and other businesses in the marketplace also have good reason to keep an eye on one another, whether to learn from each other's mistakes or to help one another out as members of a community of practice.

“What's the Business Case for That?”

You'll hear this question a lot in the business world. A business case is a special form of a business plan that explains or justifies a proposed change in the ways that the organization gets work done. This justification may be framed as a cost vs. benefits trade-off, or a balance of risks (which are probabilities of losses) vs. the costs of making the change. Depending on the nature of the proposed change, these costs may include both start-up or implementation costs, ongoing additional costs of operations and maintenance, and even disposal or contract termination costs (to decommission and remove the previous system, process, or contract arrangements). Presenting this justification to managers and leaders for decision making is known as making the business case for the proposed change.

A business plan is then developed to lay out the schedule of actions and the resources required to implement such a change; this plan also provides visibility into key progress indicators or decision points (which may or may not have been identified in the business case as part of its justification).

The SSCP needs to deal with business cases in several ways:

- On a project basis, by estimating the costs of a given information security system versus the potential impacts to the business if the system is not implemented. This determines whether or not the proposed project is cost effective (benefits exceed the cost), as well as estimating the payback period (the time, usually in years, that the costs implementing and operating the project are exceeded by accumulated savings from impacts it helped avoid). Given the rapid pace of change in systems technologies and the threat landscape, shorter payback periods—a few months at most—often make for a far more compelling business case for a change.

- At the larger, more strategic level, the business case becomes more of a fully-developed business plan, as it sets out objectives and goals, and sets priorities for them. These priorities drive which projects are well provided with funding or other resources, and which ones have to wait until resources become available. Prioritized goals also drive which information security problems should be addressed first.

We'll delve into this topic in greater depth starting in the next chapter as we look at information risk management. The more you know about how your employer plans their business, and how they know if they are achieving those plans, the better you'll be able to help assure them that the information they need is safe, secure, and reliable.

Purpose, Intent, Goals, Objectives

There are as many reasons for going into business, it seems, as there are people who create new businesses: personal visions, ambitions, and dreams; the thoughtful recognition of a need, and of one's own abilities to address it; enjoyment at doing something that others also can benefit from. How each organization transforms the personal visions and dreams of its founders into sustainable plans that achieve goals and objectives is as much a function of the personalities and people as it is the choices about the type of business itself. As an SSCP, you should understand what the company's leaders, owners, and stakeholders want it to achieve. These goals may be expressed as “targets” to achieve over a certain time frame—opening a number of new locations, increasing sales revenues by a certain amount, or launching a new product by a certain date. Other inward-facing goals might be to improve product quality (to reduce costs from scrap, waste, and rework), improve the way customer service issues are handled, or improve the quality, timeliness, and availability of the information that managers and leaders need to make more effective decisions more reliably.

Notice that each goal or objective is quickly transformed into a plan: a statement of a series of activities chosen and designed to achieve the results in the best way the business knows how to do. The plan does not become reality without it being resourced—without people, money, supplies, work spaces, and time being made available to execute that plan. Plans without resource commitments remain “good ideas,” or maybe they just remain as wishful thinking.

Business Logic and Business Processes: Transforming Assets into Opportunity, Wealth, and Success

All businesses work by using ideas to transform one set of “inputs” into another set of “outputs”; they then provide or sell those outputs to their customers at a price that (ideally) more than pays for the cost of the inputs, pays everybody's wages, and pays a dividend back to the investors. That set of ideas is key to what makes one business different from another. That initial set of ideas is perhaps the “secret sauce” recipe, the better mousetrap design, or simply being the first to recognize that one particular marketplace doesn't have anybody providing a certain product or service to its customers.

That key idea must then be broken down into step-by-step sequences of tasks and procedures that the company's managers can train people to do; even if they buy or rent machines to do many of those tasks, the detailed steps still need to be identified and described in detail. Safety constraints also have to be identified so that workers and equipment aren't injured or damaged and so that wastage of time and materials is minimized. There may also be a need for decisions to be made between steps in the process, and adjustments made or sequences of steps repeated (such as “stir until thickened” or “bake the enamel at 750 degrees Fahrenheit for one hour”).

But wait, there's more! That same systematic design of how to make the products also has to be spelled out for how to buy the raw materials, how to sell the finished products to customers, how to deal with inquiries from potential customers, and how to deal with customer complaints or suggestions for new or improved products. Taken together, this business logic is the set of ideas and knowledge that the owners and managers need in order to be able to set up the business and operate it effectively.

Business logic is intellectual property. It is a set of ideas, expressed verbally and in written form. It is built into the arrangement of jobs, tasks, and equipment, and the flow of supplies into and finished products out of the business. The business logic of a company either helps it succeed better than its competitors, or holds the company back from success in the marketplace. Knowing how to get business done efficiently—better, faster, cheaper—is a competitive advantage. Prudent business executives guard their business logic:

- Trade secrets are those parts of a company's business logic that it believes are unique, not widely known or understood in the marketplace, and not easily deduced or inferred from the products themselves. Declaring part of its business logic as a trade secret allows a company to claim unique use of it—in effect, declare that it has a monopoly on doing business in that particular way. A company can keep trade secrets as long as it wants to, as long as its own actions do not disclose those secrets to others.

- Patents are legal recognition by governments that someone has created a new and unique way of doing something. The patent grants a legal monopoly right in that idea, for a fixed length of time. Since the patent is a published document, anyone can learn how to do what the patent describes. If they start to use it in a business, they either must license its use from the patent holder (typically involving payment of fees) or risk being found guilty of patent infringement by a patents and trademarks tribunal or court of law.

As an SSCP, you probably won't be involved in determining whether an idea or a part of the company's business logic is worthy of protection as a trade secret or patentable idea, but much like the company's trademarks and copyrighted materials, you'll be part of protecting all of the company's intellectual property. That means keeping its secrets secret; keeping its in-house knowledge, ideas, and supporting data free from corruption by accident or through hostile intent; and keeping that IP available when properly authorized company team members need it.

The Value Chain

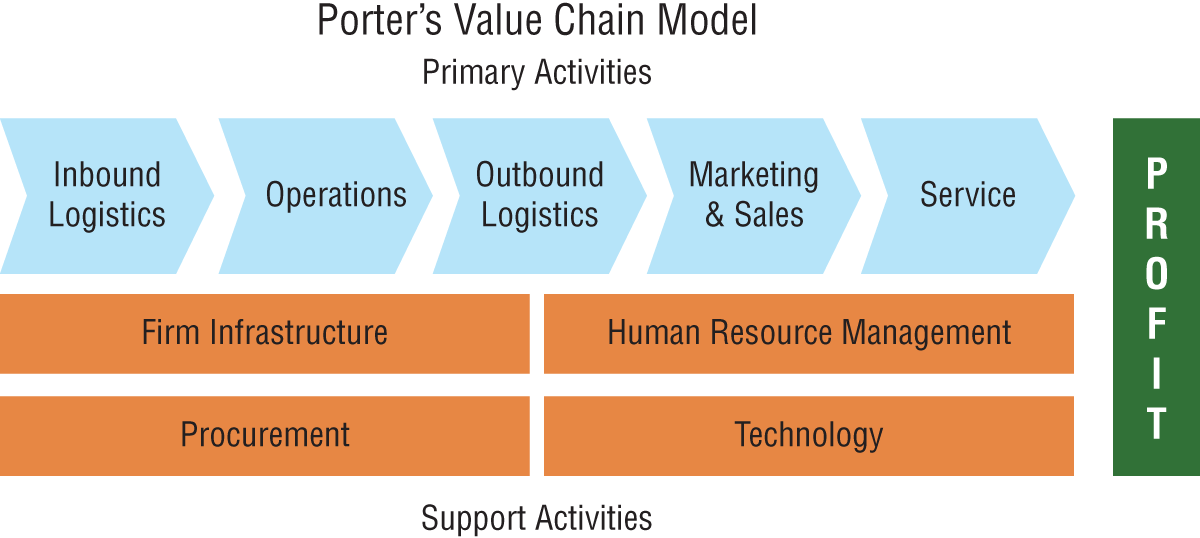

All but the simplest, most trivial business logic will require a series of steps, one after another. Michael Porter's value chain concept looks at these steps and asks a very important question about each one: does this step add value to the finished product, or does it only add cost or risk of loss? Figure 1.3 illustrates the basic value chain elements.

FIGURE 1.3 The value chain

Value chain analysis provides ways to do in-depth investigation of the end-to-end nature of what a business does, and how it deals with its suppliers and customers. More importantly, value chain analysis helps a company learn from its own experiences by continuously highlighting opportunities to improve. It does so by looking at every step of the value chain in fine detail. What supports this step? What inputs does it need? What outputs or outcomes does it produce? What kind of standards for quality, effectiveness, or timeliness are required of this step? How well does it measure up against those standards? Does this step have a history of failures or problems associated with it? What about complaints or suggestions for improvement by the operations staff or the people who interact with this step? Do any downstream (or upstream) issues exist that relate to this step and need our attention?

If you think that sounds like an idea you could apply to information security, and to providing a healthy dose of information assurance to your company's IT systems, you're right!

Value chain analysis can be done using an Ishikawa diagram, sometimes called a fault tree or fishbone diagram, such as the generic one shown in Figure 1.4. The major business process is the backbone of the fish, flowing from left to right (the head and tail are optional as diagram elements); the diagonals coming into the backbone show how key elements of the business logic are accomplished, with key items or causes of problems shown in finer and finer detail as the analysis proceeds. Clearly, a fishbone or Ishikawa diagram could be drawn for each element of a complex business process (or an information security countermeasure system), and often is.

FIGURE 1.4 Ishikawa (or “fishbone”) diagram for a value process

As an SSCP, you'll find that others in the business around you think in terms like value chain and fault tree analysis; they use diagrams like the fishbone as ways of visualizing problems and making decisions about how to deal with them. Think of them as just one more tool in your tool kit.

Being Accountable

The value chain shows us that at each step of a well-designed business process, management ought to be able to measure or assess whether that step is executing properly. If that step is not working correctly, managers can do fault isolation (perhaps with a fishbone) to figure out what went wrong. This is the essence of accountability: know what's supposed to happen, verify whether it did happen, and if it didn't, find out why.

That may seem overly simplified, but then, powerful ideas really are simple! At every level in the company, managers and leaders have that same opportunity and responsibility to be accountable. Managers and leaders owe these responsibilities to the owners of the business, to its investors and other stakeholders, as well as to its customers, suppliers, and employees. These are “bills” of services that are due and payable, every day—that is, if the manager and leader want to earn their pay!

The Three “Dues”

You will encounter these terms a lot as an SSCP, and so we'll use them throughout this book. You'll need to be able to recognize how they show up as elements of situations you'll encounter, on the job as well as on the certification exam:

- Due care is the responsibility to fully understand and accept a task or set of requirements, and then ensure that you have fully designed and implemented and are operating systems and processes to fulfill those requirements.

- Due diligence is the responsibility to ensure that the systems and processes you have implemented to fulfill a set of requirements are actually working correctly, completely, and effectively.

- Due process means that there is in fact a process that defines the right and correct way to do a particular task; that process specifies all of the correct steps that must be taken, constraints you must stay within, and requirements you must meet in order to correctly perform this task. Although we normally think of this as due process of law—meaning that the government cannot do something unless all of the legal requirements have been met—due process is also a useful doctrine to apply to any complex or important task.

If you talk with anyone in a safety-related profession or job, you'll often hear them say that “Safety rules are written in blood” as a testament to the people who were injured or killed, and the property that was damaged, before we were smart enough to write a good set of safety rules or regulations. In fact, most occupational safety laws and rules—and the power of commercial insurance companies to enforce them—come to us courtesy of generations of whistleblowers who risked their jobs and sometimes their lives to tell journalists and government officials about high-risk aspects of their life at work.

Due care means that you make sure you don't design tasks or processes that put your people or your company's assets in danger of harm or loss. Due diligence means you check up on those processes, making sure that they're being followed completely, and that they still work right. Otherwise, due process of law may shut down your business.

Financial Accounting Standards and Practices

The Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) provide an excellent example of putting these three “dues” to work in a business. GAAP has been developed over time by accountants, lawyers, business leaders, and government regulators to provide a common set of practices for keeping track of all of the financial aspects of a business's activities. By itself, GAAP does not have the force of law. However, many laws require different kinds of businesses to file different statements (such as tax returns) with their governments, which can be subject to audits, and the audits will be subject to GAAP standards. Insurance companies won't insure businesses whose recordkeeping is not up to GAAP standards, or they will charge those businesses higher premiums on the insurance they will write. Banks and investment firms may not lend to such businesses, or will do so only at higher interest costs.

Part of GAAP includes dictating the standards and practices for how the company ensures that only the right people can create, alter, print, download, or delete the financial records of the business. Internal controls over financial reporting systems (ICFRs or ICOFRS) are the ways in which organizations implement these standards and practices. With cybercrime of all forms (not just ransomware attacks) continuing to increase, SSCPs will have an even greater role in helping their organizations implement ICFRs and then assist in continually assessing their operational effectiveness. As an SSCP, you'll be implementing and maintaining many of the information security systems and controls that implement those GAAP requirements.

And…you'll be auditing those information security systems too, in part as more of your duties to help the company be GAAP-compliant.

Many laws exist in many nations that go further than GAAP in dictating the need to keep detailed records of how each step in a business is done, who did it, when and where, and what the results or outcomes of that step turned out to be. These laws also spell out significant requirements for controlling who has access to all of those records, and dictate how long the company must keep what kind of records on hand to answer audits or litigation. Strangely enough, they also dictate when to safely dispose of records in order to help protect the company from spending too much time and money searching old archives of records in response to complaints! (The SSCP may have a role to play in the destruction or safe disposal of outdated business records too.)

Ethical Accountability

Business ethics are a set of standards or codes of behaviors that most of the members of a business marketplace or the societies it serves believe or hold to be right and necessary for the safe operation of that marketplace. In many respects, the common elements of nearly every ethical code apply in business—honesty, truthfulness, integrity, and being true to one's given word or pledge on a contract or agreement are all behaviors that are vital to making business work. (As a proof, think about doing business with a company or a person who you know is not honest or truthful.…)

Some marketplaces and some professions go further than the basics and will work together to agree to a more explicitly expressed code of ethics. Quite often these codes of ethics are made public so that prospective customers (and government regulators) will know that the marketplace will be self-regulating.

Legal Accountability (Criminal and Civil)

We've mentioned a few of the many laws that can hold a business professional's feet to the fire. We're not going to mention them all! Do be aware that they fall into two broad categories that refer to the kind of punishment (or liability) you can find yourself facing if you are found guilty of violating them—namely, criminal law and civil law. Both are about violations of the law, by the way! Criminal law has its roots in violations of law such as physical assault or theft; the victims or witnesses inform the government, and the government prosecutor files a complaint against a defendant (who may then be subject to arrest or detainment by the police, pending the outcome of the trial). Criminal law usually has a higher standard of proof of guilt, and compared to civil law, it has tougher standards regarding the use of evidence and witness testimony by prosecution or the defendant. Civil law typically involves failure to fulfill your duties to society, such as failing to pay your property taxes; a civil law proceeding can foreclose on your property and force its sale in such a case, but (in most jurisdictions) it cannot cause you to be punished with time in jail. A subset of civil law known as tort law is involved with enforcement of private contracts (which make up the bulk of business agreements).

The Concept of Stewardship

If you think about the concepts of the “three dues,” you see an ancient idea being expressed—the idea of being a good steward. A steward is a person who stands in the place of an absent owner or ruler and acts in that absent person's best interests. A good steward seeks to preserve and protect the value of the business, lands, or other assets entrusted to their care, and may even have freedom to take action to grow, expand, or transform those assets into others as need and opportunity arise. You may often hear people in business refer to “being a good steward” of the information or other assets that have been entrusted to them. In many respects, the managing directors or leaders of a business are expected and required to be good stewards of that business and its assets—whether or not those same individuals might be the owners of the business.

Who Runs the Business?

We've shown you how businesses create their business logic and build their business processes that are their business, and we've mentioned some of the many decision makers within a typical business. Let's take a quick summary of the many kinds of job titles you may find as you enter the world of business as an SSCP. This is not an exhaustive or authoritative list by any means—every business may create its own job titles to reflect its needs, the personalities of its founders, and the culture they are trying to inculcate into their new organization. That said, here are some general guidelines for figuring out who runs the business, and who is held accountable for what happens as they do.

Owners and Investors

Owners or majority shareholders often have a very loud voice in the way that the company is run. In most legal systems, the more active an owner or investor is in directing day-to-day operation of the company, the more responsible (or liable) they are for damages when or if things go wrong.

Boards of Directors

Most major investors would like a bit of distance from the operation of the company and the liabilities that can come with that active involvement, and so they will elect or appoint a group of individuals to take long-term strategic responsibility for the company. This board of directors will set high-level policy, spell out the major goals and objectives, and set priorities. The board will usually appoint the chief officers or managing directors of the company. In most cases, board membership is not a full-time job—a board member is not involved day to day with the company and the details of its operation, unless there is a special need, problem, or opportunity facing the company.

Managing or Executive Directors and the “C-Suite”

The board of directors appoints a series of executive officers who run the company on a day-to-day basis. Typically, the top executive will be known as the managing director, the president, or the chief executive officer (CEO) of the company. In similar fashion, the most senior executives for major functional areas such as Operations, Finance, and Human Resources Management might have a title such as chief operations officer (COO) or chief financial officer (CFO). These senior directors are often collectively known as the “C-Suite,” referring to the common practice of having all of their offices, desks, etc., in one common area of the company's business offices. (In cultures that use the Managing Director title instead of CEO, this area of the company's offices and the group of people who hold those roles might be known as the Directors instead.)

Other members of the “C-Suite” team that an SSCP may have more need to be aware of might include:

- Chief information officer (CIO), responsible for corporate communications, information strategy, and possibly information systems

- Chief technology officer (CTO), responsible for all of the IT and telecommunications technologies, primarily focused on the long-term strategy for their modernization and use

- Chief knowledge officer (CKO), who looks to strategies and plans to help the company grow as a learning organization

- Chief security officer (CSO), responsible for keeping all assets and people safe and secure

- Chief information security officer (CISO), whose focus is on information security, information systems security, and information technology security

Just because the word “chief” is in a duty title does not necessarily make its holder a resident of the C-Suite. This will vary company by company. A good, current organizational chart will help you know who sits where, and will give you a start on understanding how they relate to your duties, responsibilities, and opportunities as an SSCP.

Layers of Function, Structure, Management, and Responsibility

It's a common experience that if one person tries to manage the efforts of too many people, at some point, they fail. This span of control is typically thought to hit a useful maximum of about 15 individuals; add one more to your 15-person team, and you start to have too little time to work with each person to help make sure they're working as effectively as they can, or that you've taken care of their needs well. Similarly, if as a manager you have too many “direct reports” in too many geographically separate locations, spanning too many time zones, your ability to understand their needs, problems, and opportunities becomes very limited. Organizations historically cope with this by introducing layers of management and leadership, from work unit up through groups, departments, divisions, and so on. What each of these levels of responsibility is called, and how these are grouped together, differs from company to company.

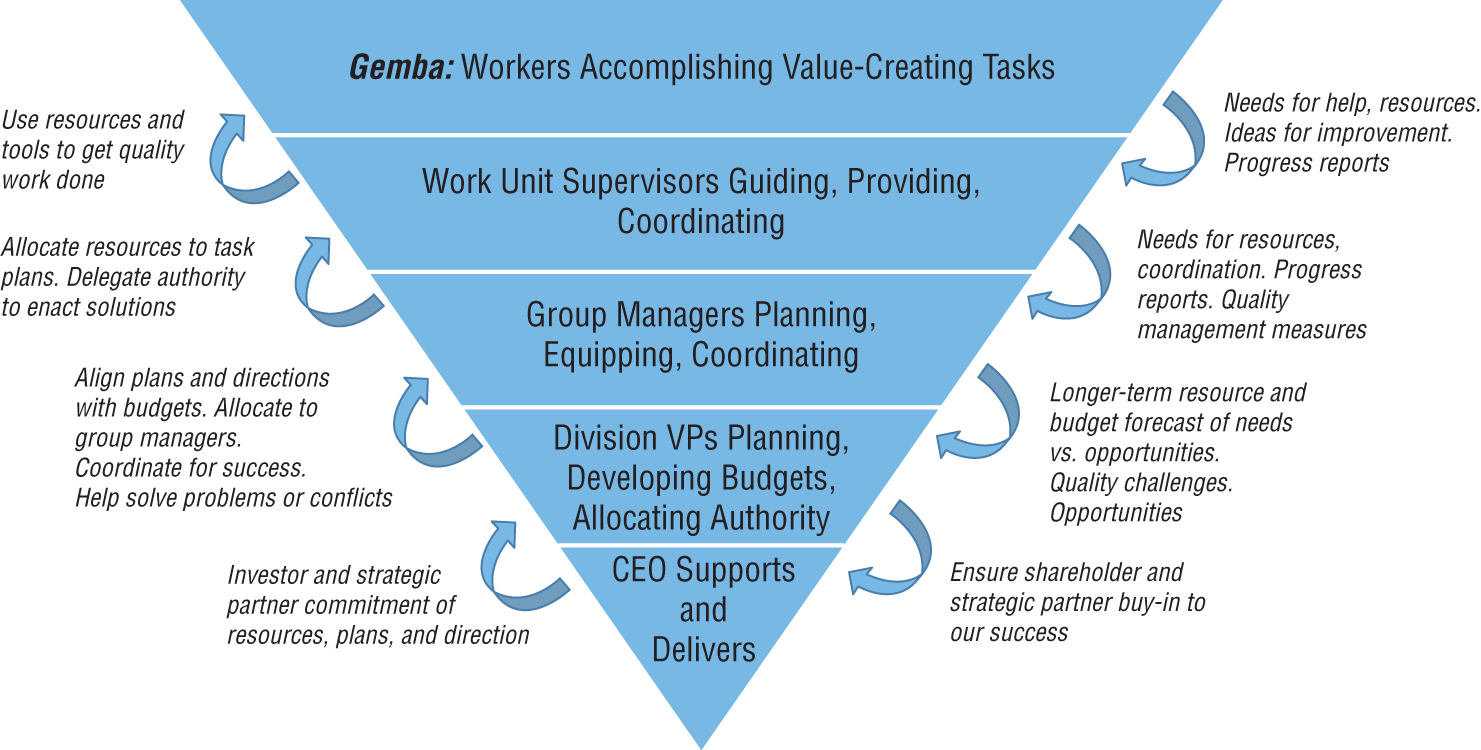

One way to look at this is with a pyramid chart, as shown in Figure 1.5. This is normally shown with the CEO or commanding general at the top, and conveys a sense that each level below is there to translate that senior leader's decisions into finer and finer detail, and pass them down to the next level. Finally, these directives get to the workers at the bottom of the pyramid—the ones who actually put tools to machines on the assembly line, or who drive the delivery trucks or take the customer orders and put them into the sales and fulfillment systems.

FIGURE 1.5 The organization chart as pyramid (traditional view)

Managers manage by measuring, or so they say. Line managers—the first level of supervisors who are accountable for the work that others do—often require a lot of visibility into the way individual workers are getting their work done. In quality management terms, the place that work actually gets done is called the gemba, a word the West has borrowed from the Japanese. Walking the gemba has in some companies become how they refer to managers walking through the work areas where the real value-added work is getting done, by the people who are hands-on making the products or operating the machines and systems that make the business of business take place. This has given rise to the inverted organizational pyramid, which sees the chief at the bottom of the picture, supporting the work of those in successive layers above him or her; finally, at the top of the pyramid is the layer of the workers at the gemba who are the ones on whom the business really depends for its survival and success. All of those managers and administrators, this view says, only exist for one reason: to organize, train, equip, and support the workers at the gemba. See Figure 1.6.

FIGURE 1.6 The inverted pyramid supports work at the gemba

As an information technology professional, this inverted pyramid view should speak to you. You do your work as an SSCP not because your job is valuable to the company by itself, but because doing your job enables and empowers others to get their jobs done better. SSCPs and others in the IT security team need to have direct, open, and trustworthy lines of communication with these true “information workers” in the organization. Policy and strategy come from the pointy end of the pyramid, whereas real day-to-day operational insight comes from the people “on the firing line,” doing the actual work.

Plans and Budgets, Policies, and Directives

High-level goals and objectives are great to plan with, but they don't get business done on a day-to-day basis. The same process that translated the highest-level business logic down into steps that can be done on the assembly line or the sales floor have also allocated budget and resources to those work units; the work unit managers have to account for success or failure, and for resource expenditure. More business logic, in the form of policy documents, dictates how to translate those higher-level plans and budgets down to the levels of the work unit managers who actually apply those resources to get tasks accomplished. Policies also dictate how they should measure or account for expenses, and report to higher management about successes or problems.

Summary

We've covered a lot of ground in this chapter as we've built the foundations for your growth as SSCPs and your continued study of information systems security and assurance. We put this in the context of business because the nature of competition, planning, and accountability for business can be much harsher than it is in any other arena (witness the number of small businesses that fail in their first few years). Successful businesses are the ones that can translate the hopes and dreams of their founders into solid, thoughtful business logic; and as we say, that investment in business logic can become the key to competitive advantage that a business can have in its chosen marketplace. Keeping that business logic safe and secure requires the due care and due diligence of all concerned—including the SSCPs working with the business on its information systems.

Exam Essentials

- Know how to differentiate between data, information, knowledge, and wisdom. This hierarchy of data to knowledge represents the results of taking the lower-level input (i.e., data) and processing it with business logic that uses other information you've already learned or processed so that you now have something more informative, useful, or valuable. Data might be the individual parts of a person's home address; when you get updates to this data and compare it to what you have on file, you conclude that they have moved to a new location (thus, you have created information). You might produce knowledge from information like this if you look across all of your contact information and see that a lot of people change their address two or three times per year. Perhaps they're “snowbirds,” moving with the seasons. Longer, deeper looks at such knowledge can produce powerful conclusions that you could apply in new situations.

- Explain the difference between information, information systems, and information technology systems. Information is what people use, think with, create, and make decisions with. Information systems are the business logic or processes that people use as they do this, regardless of whether the information is on paper, in electronic form, or only tacit (in their own minds). Information technologies such as paper and pen, computers, and punch cards are some of the ways you record information and then move, store, or update those recordings to achieve some purpose.

- Explain the difference between due care and due diligence. Due care is making sure that you have designed, built, and used all the necessary and prudent steps to satisfy all of your responsibilities. Due diligence is continually monitoring and assessing whether those necessary and prudent steps are achieving required results and that they are still necessary, prudent, and sufficient.

- Relate nonrepudiation and authenticity to the duties of due care, due diligence, and due process. There are many ways to relate security concepts to these three duties. For example, due care requires that directives, orders, or commands to take actions are authentic; that is, they are validated or confirmed to be coming from duly authorized persons or entities. Ongoing monitoring, as part of due diligence, should identify attempts to reverse or undo decisions, commands, or directives (such as agreements to make purchases or payments), and prevent them unless properly authorized. Nonrepudiation and authenticity support this. All organizations need ways to recognize when they've made a wrong decision and need to change their plans; due process requires that thoughtful, logical procedures be used to overturn any decision.

- Describe the need for making a business case related to information security issues. Many information security issues or problems will require changes to the ways in which the organization gets work done. These changes will cost time, money, and effort to make, and may have ongoing costs as well. Justifying the need for those changes is done with a business case, which documents and explains the rationale for the change. The business case usually does this via trade-off analysis, such as cost-benefits or risks versus rewards.

- Explain what business logic is and its relationship to information security. Business logic is the set of rules that dictate or describe the processes that a business uses to perform the tasks that lead to achieving the required results, goals, or objectives. Business logic is often called know-how, and it may represent insights into making better products or being more efficient than is typical and, as such, generates a competitive advantage for the business. It is prudent to protect business logic so that other unauthorized users, such as competitors, do not learn from it and negate its advantage to the business.

- Explain the roles of CEOs or managing directors in a modern business. CEOs or managing directors are the most senior, responsible individuals in a business. They have ultimate due care and due diligence responsibility for the business and its activities. They have authority over all activities of the company and can direct subordinate managers in carrying out those responsibilities. They may report to a board of directors, whose members have long-term, strategic responsibility for the success of the business.

- Explain what a stakeholder is in the context of a business. A stakeholder is a person or organization that has an interest in or dependence on the successful operation of the business. Stakeholders could be investors; employees of the business; its strategic partners, vendors, or customers; or even its neighbors. Not all interests are directly tied to profitable operation of the business—neighbors, for example, may have a stake in the company operating safely and in ways that do not cause damage to their own properties or businesses.

- Explain what accountability means to information security professionals. Accountability measures the ways people or organizations behave to determine if they are fulfilling their obligations. Organizations must implement some form of internal controls, whether for financial or other obligations, to demonstrate that they are holding themselves accountable. These controls must be trustworthy and reliable; information security professionals contribute to ensuring this.

Review Questions

- How do you turn data into knowledge?

- These are both names for the same concepts, so no action is required.

- You use a lot of data to observe general ideas and then test those ideas with more data you observe, until you can finally make broad, general conclusions. These conclusions are what are called knowledge.

- You apply data smoothing and machine learning techniques, and the decision rules this produces are called knowledge.

- You have to listen to the data to see what it's telling you, and then you'll know.

- Which is more important to a business—its information or its information technology?

- Neither, since it is the business logic and business processes that give the business its competitive advantage.

- The information is more important, because all that the information technology does is make the information available to people to make decisions with.

- The information technology is more important, because without it, none of the data could be transformed into information for making decisions with.

- Both are equally important, because in most cases, computers and communications systems are where the information is gathered, stored, and made available.

- As the IT security director, Paul does not have anybody looking at systems monitoring or event logging data. Which set of responsibilities is Paul in violation of?

- Due care

- Due diligence

- None of the above

- Both due care and due diligence

- Business logic is:

- A set of tasks that must be performed to achieve an objective within cost and schedule constraints

- The set of rules and constraints that drive a business to design a process that gets business done correctly and effectively

- Software and data used to process transactions and maintain accounts or inventories correctly

- The design of processes to achieve an objective within the rules and constraints the business must operate within

- How does business logic relate to information security?

- Business logic represents decisions the company has made, and that may give it a competitive advantage over others in the marketplace; it needs to be protected from unauthorized disclosure or unauthorized change. Processes that implement the business logic need to be available to be run or used when needed. Thus, confidentiality, integrity, and availability apply.

- Business logic for specific tasks tends to be common across many businesses in a given market or industry; therefore, there is nothing confidential about it.

- Business logic should dictate the priorities for information security efforts.

- Business logic is important during process design; in daily operations, the company uses its IT systems to get work done, so it has no relationship to operational information security concerns.

- Protection of intellectual property (IP) is an example of what kind of information security need?

- Privacy

- Confidentiality

- Availability

- Integrity

- John works as the chief information security officer for a medium-sized chemical processing firm. Which of the following groups of people would not be stakeholders in the ongoing operation of this business?

- State and local tax authorities

- Businesses in the immediate neighborhood of John's company

- Vendors, customers, and others who do business with John's company

- The employees of the company

- Due diligence means:

- Paying your debts completely, on time

- Doing what you must do to fulfill your responsibilities

- Making sure that actions you've taken to fulfill your responsibilities are working correctly and completely

- Reading and reviewing the reports from subordinates or from systems monitoring data

- Do the terms cybersecurity, information assurance, and information security mean the same thing? (Choose all that apply.)

- No, because cyber refers to control theory, and therefore cybersecurity is the best term to use when talking about securing computers, computer networks, and communications systems.

- Yes, but each finds preference in different markets and communities of practice.

- No, because cybersecurity is about computer and network security, information security is about protecting the confidentiality and integrity of the information, and information assurance is about having reliable data to make decisions with.

- No, because different groups of people in the field choose to interpret these terms differently, and there is no single authoritative view.

- What do we use protocols for? (Choose all that apply.)

- To conduct ceremonies, parades, or how we salute superiors, sovereigns, or rulers

- To have a conversation with someone and keep disagreement from turning into a hostile, angry argument

- To connect elements of computer systems together so that they can share tasks and control each other

- As abstract design tools when we are building systems, although we don't actually build hardware or software that implements a protocol

- None of the above

- Public health measures often require that immunization or treatment records would be made available to travel operators to use in determining if each passenger or crew member was safe to be allowed on board. Which of the following would be the best description of this process?

- Data processing

- Information management

- Knowledge management

- Information processing

- None of the above

- Public health measures often require that a travel operator gather and maintain current government-issued criteria or guidelines for making a board/no-board decision about each passenger. These change frequently and often contradict each other. At one airline, managers relied on informal, verbal means of directing their passenger agents as to how to make sense of these instructions. This is a process that relied on:

- Explicit knowledge

- Data smoothing

- Tacit knowledge

- Business logic

- None of the above

- During public health emergencies such as pandemics, government-issued guidance to travel operators such as airlines and cruise ships can change frequently. Suppose one cruise ship operator has well-defined, written guidance to its passenger agents, which they update as quickly as possible when circumstances change. Which ethical or legal duty or duties would this be fulfilling? (Choose all that apply.)

- Due process

- Due care

- Due diligence

- Accountability

- Government regulations may require that travel operators verify that each passenger have full and current immunizations in order to travel. Suppose that one airline fails to put in place controls or processes to validate that immunization or test results sent to them by a prospective passenger are not, in fact, counterfeit or forgeries. This would mean their information security approach is failing to achieve which of the following?

- Confidentiality

- Integrity

- Availability

- Nonrepudiation

- Authenticity

- During the Covid-19 pandemic, one airline realized that they need to make changes to improve the reliability of their decisions about boarding or declining passengers, by ensuring the authenticity of the immunization data they submitted. What type of planning process might they use to come to this realization?

- Business case

- Business logic

- Business plan

- GAAP analysis

- Which statement best describes information systems?

- The computers, networks, and communications elements that are used to gather, process, store, and distribute information

- The operating systems, applications, and databases used to gather, store, process, and distribute information

- The set of tools and processes used to transform data into information

- The set of information, processes, and technologies, and interfaces that work together to suit the needs of the system's owners and users

- Many investment brokerages allow their customers to make online purchase and sales orders for stocks, options, commodities, or other investments. The brokerage makes that transaction immediately after the customer clicks the Submit button. Which information security attribute or characteristic protects the brokerage from the customer claiming that they never sent in a particular order?

- Confidentiality

- Integrity

- Availability

- Nonrepudiation

- Authenticity

- Which statement best characterizes the difference between a business case and a business plan for an information security project?

- The business case looks at law and regulations as the source of detailed requirements, while the business plan uses broad, general statements about goals and objectives as the basis of its plan.

- The business case looks at longer-term, strategic ways to accomplish objectives; the business plan specifies the details about each element in achieving that plan.

- The business case provides a compelling argument, in cost-benefits or risks-versus-rewards terms, for making an immediate or near-term change in security practices; the business plan looks at longer-term objectives, prioritizes them, and lays out a strategy to achieve them with.

- None of the above.

- What might be the best reason for a business case be able to use a short payback period, rather than a longer one, as part of its argument?

- The threat landscape changes very quickly.

- Operational or business needs may change rapidly and unpredictably.

- Most people, managers and leaders included, cannot make meaningful predictions too far into the future; the shorter the payback period, the more they will perceive the proposed change as being valuable.

- None of the above.

- How do ethical concepts of accountability relate to information security?

- Ethical concepts of accountability directly relate to concepts of trust and reliability, which directly relate to information security concepts.

- They don't relate very well, since most ethical concepts are up to the individual to decide.

- They don't relate very well, as information security concepts are derived from legal ideas about accountability, and attempting to legislate ethics does not work.

- Indirectly, as these ethics concepts get expressed into laws and regulations, and these are what dictate information security concepts and practices.