Previous Chapter | Next Chapter | Table of Contents

Top 5 Reasons to Go | Quick Bites | Getting There | Making the Most of Your Time | The Haight | The Castro | Noe Valley

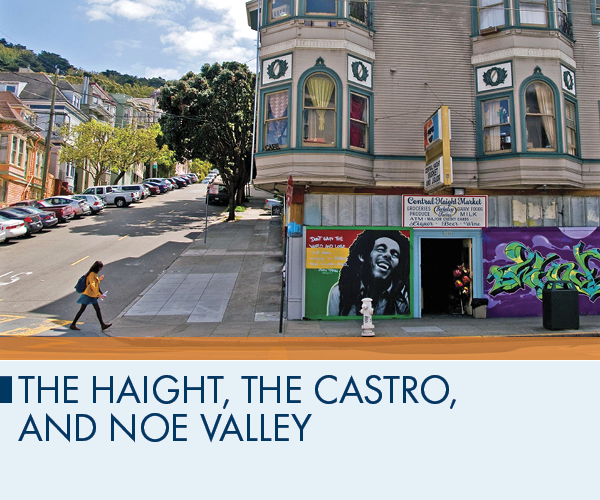

These distinct neighborhoods are where the city’s soul resides. They wear their personalities large and proud, and all are perfect for just strolling around. Like a slide show of San Franciscan history, you can move from the Haight’s residue of 1960s counterculture to the Castro’s connection to 1970s and ‘80s gay life to 1990s gentrification in Noe Valley. Although historic events thrust the Haight and the Castro onto the international stage, both are anything but stagnant—they’re still dynamic areas well worth exploring.

During the 1960s the siren song of free love, peace, and mind-altering substances lured thousands of young people to the Haight, a neighborhood just east of Golden Gate Park. By 1966 the area had become a hot spot for rock artists, including the Grateful Dead, Jefferson Airplane, and Janis Joplin. Some of the most infamous flower children, including Charles Manson and People’s Temple founder Jim Jones, also called the Haight home.

Today the ’60s message of peace, civil rights, and higher consciousness has been distilled into a successful blend of commercialism and progressive causes: the Haight Ashbury Free Medical Clinic, founded in 1967, survives at the corner of Haight and Clayton, while throwbacks like Bound Together Books (the anarchist book collective), the head shop Pipe Dreams, and a bevy of tie-dye shops all keep the Summer of Love alive in their own way. The Haight’s famous political spirit—it was the first neighborhood in the nation to lead a freeway revolt, and it continues to host regular boycotts against chain stores—survives alongside some of the finest Victorian-lined streets in the city. And the kids continue to come: this is where young people who end up on San Francisco’s streets most often gather. Visitors tend to find the Haight either edgy and exhilarating or scummy and intimidating (the panhandling here can be aggressive).

Just over Buena Vista Hill from Haight Street, nestled at the base of Twin Peaks, lies the brash and sassy Castro District—the social, political, and cultural center of San Francisco’s thriving gay (and, to a lesser extent, lesbian) community. This neighborhood is one of the city’s liveliest and most welcoming, especially on weekends. Streets teem with folks out shopping, pushing political causes, heading to art films, and lingering in bars and cafés. Hard-bodied men in painted-on tees cruise the cutting-edge clothing and novelty stores, and pairs of all genders and sexual persuasions hold hands. Brightly painted, intricately restored Victorians line the streets here, making the Castro a good place to view striking examples of the architecture San Francisco is famous for.

Still farther south lies Noe Valley—also known as Stroller Valley for its relatively high concentration of little ones—an upscale but relaxed enclave that’s one of the city’s most desirable places to live. Church Street and 24th Street, the neighborhood’s main thoroughfares, teem with laid-back cafés, kid-friendly restaurants, and comfortable, old-time shops. You can also see remnants of Noe Valley’s agricultural beginnings: Billy Goat Hill (at Castro and 30th streets), a wild-grass hill often draped in fog, is named for the goats that grazed here right into the 20th century.

Top 5 Reasons to Go

Castro Theatre: Take in a film at this gorgeous throwback and join the audience shouting out lines, commentary, and songs. Come early and let the Wurlitzer set the mood.

Sunday brunch in the Castro: Recover from Saturday night (with the entire community) at one of the top brunch destinations: Lime (2247 Market), Chow (215 Church), or Tangerine (3499 16th).

Vintage shopping in the Haight: Find the perfect chiffon dress at La Rosa, a pristine faux-leopard coat at Held Over, or the motorcycle jacket of your dreams at Buffalo Exchange.

24th Street stroll: Take a leisurely ramble down lovable Noe Valley’s main drag, lined with unpretentious cafés, comfy eateries, and cute one-of-a-kind shops.

Cliff’s Variety: Stroll the aisles of the Castro’s “hardware” store (479 Castro St.) for lightbulbs, hammers, and pipes (as well as false eyelashes, tiaras, and feather boas) to get a feel for this neighborhood’s full-tilt flair.

Quick Bites

Lovejoy’s Tea Room.

The tearoom is a homey jumble, with its lace-covered tables, couches, and mismatched chairs set among the antiques for sale. High tea and cream tea are served, along with traditional English-tearoom “fayre.” | 1351 Church St.,

at Clipper St.,

Noe Valley | 94114 | 415/648–5895 | www.lovejoystearoom.com.

Coffee to the People.

Get a jolt of organic fair-trade caffeine and a bit of revolutionary spirit at this book-filled café. | 1206 Masonic Ave.,

at Haight St.,

Haight | 94117 | 415/626–2435.

Philz Coffee.

The aroma alone might lure you into Philz Coffee, just off the main drag of Castro Street. Its fedora-hung, cramped space gives off a casual vibe, but don’t be fooled: the city’s second most-popular place (after Blue Bottle) for the über-serious coffee drinker serves up the strongest handcrafted cup of joe in town. | 4023 18th St.,

Castro | 94114 | 415/875–9656.

Hanging Out in the Haight

There’s no finer way to ease into a lazy day in the Haight than with a towering stack of cornmeal pancakes at Kate’s Kitchen. After conquering that mountain of chow, stagger over six blocks to another challenge: the hike up Buena Vista Park, an occasionally dodgy green space with a payoff of sweeping city and bridge views. Back on Haight Street, 1960s flashbacks await at vintage head shop Pipe Dreams and the brightly colored tie-dye shop Positively Haight Street. The fabled Haight-Ashbury intersection can be anticlimactic; walk a block south to the Grateful Dead house.

Back in the here and now, head to Held Over, where you’ll find gorgeous vintage clothes minus the secondhand jumble, then venture into taxidermy–vintage jewelry–goth gallery Loved to Death and pick up a pair of beetle-wing earrings or a human-tooth bracelet on your way to Amoeba, the used-vinyl-and-CD mecca. When you eventually emerge, you can do some shoe-gazing at John Fluevog before schlepping your finds back to Cha Cha Cha to indulge in some sangria and spicy Caribbean-ish fare. Then it’s off to retro-swank Aub Zam Zam for a nightcap.

—Denise M. Leto

Making the Most of Your Time

The Upper Haight is only a few blocks long, and although there are plenty of shops and amusements, an hour or so should be enough. Many restaurants here cater to the morning-after crowd, so this is a great place for brunch. With the prevalence of panhandling in this area, you may be most comfortable here during the day.

The Castro, with its fun storefronts, invites unhurried exploration; allot at least 60 to 90 minutes. Visit in the evening to check out the lively nightlife, or in the late morning—especially on weekends—when the street scene is hopping.

Hippie History

The eternal lure for twentysomethings, cheap rent, first helped spawn an indelible part of SF’s history and public image. In the early 1960s young people started streaming into the sprawling, inexpensive Victorians in the area around the University of San Francisco. The new Haight locals earnestly planned a new era of communal living, individual empowerment, and expanded consciousness.

Golden Gate Park’s Panhandle, a thin strip of green on the Haight’s northern edge, was their public gathering spot—the site of protests, concerts, food giveaways, and general hanging out. In 1967 George Harrison strolled up the park’s Hippie Hill, borrowed a guitar, and played for a while before someone finally recognized him. He led the crowd, Pied Piper–style, into the Haight.

At first the counterculture was all about sharing and taking care of one another—a good thing, considering most hippies were either broke or had renounced money. They hadn’t renounced food, though, and the daily free “feeds” in the Panhandle were a staple for many. The Diggers, an anarchist street-theater group, were known for handing out bread shaped like the big coffee cans they baked it in. (The Diggers also gave us immortal phrases such as “Do your own thing.”)

At the time, the U.S. government, Harvard professor Timothy Leary, a Stanford student named Ken Kesey, and the kids in the Haight were all experimenting with LSD. Acid was legal, widely available, and usually given away for free. At Kesey’s all-night parties, called “acid tests,” a buck got you a cup of “electric” Kool-Aid, a preview of psychedelic art, and an earful of the house band, the Grateful Dead. LSD was deemed illegal in 1966, and the kids responded by staging a Love Pageant Rally, where they dropped acid tabs en masse and rocked out to Janis Joplin and the Dead.

Things crested early in 1967, when between 10,000 and 50,000 people (“depending on whether you were a policeman or a hippie,” according to one hippie) gathered at the Polo Field in Golden Gate Park for the Human Be-In of the Gathering of the Tribes. Allen Ginsberg and Timothy Leary spoke, the Dead and Jefferson Airplane played, and people costumed with beads and feathers waved flags, clanged cymbals, and beat drums. A parachutist dropped onto the field, tossing fistfuls of acid tabs to the crowd. America watched via satellite, gape-mouthed—it was every conservative parent’s nightmare.

Later that year, thousands heeded Scott McKenzie’s song “San Francisco,” which promised “For those who come to San Francisco, Summertime will be a love-in there.” The Summer of Love swelled the Haight’s population from 7,000 to 75,000; people came both to join in and to ogle the nutty subculture. But degenerates soon joined the gentle people, heroin replaced LSD, crime was rampant, and the Haight began a fast slide.

Hippies will tell you the Human Be-In was the pinnacle of their scene, while the Summer of Love came from outside—a media creation that turned their movement into a monster. Still, the idea of that fictional summer still lingers, and to this day pilgrims from all over the world come to the Haight to search for a past that never was.

A loop through Noe Valley takes about an hour. With its popular breakfast spots and cafés, this neighborhood is a good place for a morning stroll. After you’ve filled up, browse the shops along 24th and Church streets.

Getting There

The Castro is the end of the line for the F-line, and both the Castro and Noe Valley are served by the J–Church Metro. The only public transit that runs to the Haight is the bus; take the 71–Haight/Noriega from Union Square or the 6–Parnassus from Polk and Market. If you’re on foot, keep in mind that the hill between the Castro and Noe Valley is very steep.

Castro and Noe Walk

The Castro and Noe Valley are both neighborhoods that beg to be walked—or ambled through, really, without time pressure or an absolute destination. Hit the Castro first, beginning at Harvey Milk Plaza under the gigantic rainbow flag. If you’re going on to Noe Valley, first head east down Market Street for the cafés, bistros, and shops, then go back to Castro Street and head south, past the glorious art-deco Castro Theatre, checking out boutiques and cafés along the way (Cliff’s Variety, at 479 Castro Street, is a must). To tour Noe Valley, go east down 18th Street to Church (at Dolores Park), and then either strap on your hiking boots and head south over the hill or hop the J–Church to 24th Street, the center of this rambling neighborhood.

The Haight

Top Attractions

Haight-Ashbury Intersection.

On October 6, 1967, hippies took over the intersection of Haight and Ashbury streets to proclaim the “Death of Hip.” If they thought hip was dead then, they’d find absolute confirmation of it today, what with the only tie-dye in sight on the famed corner being Ben & Jerry’s storefront.

Two Haights

The Haight is actually composed of two distinct neighborhoods: the Lower Haight runs from Divisadero to Webster; the Upper Haight, immediately east of Golden Gate Park, is the part people tend to call Haight-Ashbury (and the part that’s covered here). San Franciscans come to the Upper Haight for the myriad vintage clothing stores concentrated in its few blocks, bars with character, restaurants where huge breakfast portions take the edge off a hangover, and Amoeba, the best place in town for new and used CDs and vinyl. The Lower Haight is a lively, grittier stretch with several well-loved pubs and a smattering of niche music shops.

Everyone knows the Summer of Love had something to do with free love and LSD, but the drugs and other excesses of that period have tended to obscure the residents’ serious attempts to create an America that was more spiritually oriented, more environmentally aware, and less caught up in commercialism. The Diggers, a radical group of actors and populist agitators, for example, operated a free shop a few blocks off Haight Street. Everything really was free at the free shop; people brought in things they didn’t need and took things they did. (The group also coined immortal phrases like “Do your own thing.”)

Among the folks who hung out in or near the Haight during the late 1960s were writers Richard Brautigan, Allen Ginsberg, Ken Kesey, and Gary Snyder; anarchist Abbie Hoffman; rock performers Marty Balin, Jerry Garcia, Janis Joplin, and Grace Slick; LSD champion Timothy Leary; and filmmaker Kenneth Anger. If you’re keen to feel something resembling the hippie spirit these days, there’s always Hippie Hill, just inside the Haight Street entrance of Golden Gate Park. Think drum circles, guitar players, and whiffs of pot smoke. | Haight.

The Evolution of Gay San Francisco

San Francisco’s gay community has been a part of the city since its earliest days. As a port city and a major hub during the 19th-century gold rush, San Francisco became known for its sexual openness along with all its other liberalities. But a major catalyst for the rise of a gay community was World War II.

During the war, hundreds of thousands of servicemen cycled through “Sodom by the Sea,” and for most, San Francisco’s permissive atmosphere was an eye-opening experience. The army’s “off-limits” lists of forbidden establishments unintentionally (but effectively) pointed the way to the city’s gay bars. When soldiers were dishonorably discharged for homosexual activity, many stayed on.

Scores of these newcomers found homes in what was then called Eureka Valley. When the war ended, the predominantly Irish-Catholic families in that neighborhood began to move out, heading for the ‘burbs. The new arrivals snapped up the Victorians on the main drag, Castro Street.

The establishment pushed back. In the 1950s San Francisco’s police chief vowed to crack down on “perverts,” and the city’s gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender residents lived in fear of getting caught in police raids. (Arrest meant being outed in the morning paper.) But harassment helped galvanize the community. The Daughters of Bilitis lesbian organization was founded in the city in 1955; the gay male Mattachine Society, started in Los Angeles in 1950, followed suit with an SF branch.

By the mid-1960s these clashing interests gave the growing gay population a national profile. The police upped their policy of harassment, but overplayed their hand. In 1965 they dramatically raided a New Year’s benefit event, and the tide of public opinion began to turn. The police were forced to appoint the first-ever liaison to the gay community. Local gay organizations began to lobby openly. As one gay participant noted, “We didn’t go back into the woodwork.”

The 1970s—thumping disco, raucous street parties, and gay bashing—were a tumultuous time for the gay community. Thousands from across the country flocked to San Francisco’s gay scene. Eureka Valley had more than 60 gay bars, the bathhouse scene in SoMa (where the leather crowd held court) was thriving, and graffiti around town read “Save San Francisco—Kill a Fag.” When the Eureka Valley Merchants Association refused to admit gay-owned businesses in 1974, camera shop owner Harvey Milk founded the Castro Valley Association, and the neighborhood’s new moniker was born. Milk was elected to the city’s Board of Supervisors in 1977, its first openly gay official (and the inspirational figure for the Oscar-winning film Milk).

San Francisco’s gay community was getting serious about politics, civil rights, and self-preservation, but it still loved a party: 350,000 people attended the 1978 Gay Freedom Day Parade, where the rainbow flag debuted. But on November 27, 1978, Milk and Mayor George Moscone were gunned down in City Hall by enraged former city council member Dan White. Thousands marched in silent tribute out of the Castro down to City Hall.

When the killer got a relatively light conviction of manslaughter, the next march was not silent. Another crowd of thousands converged on City Hall, this time smashing windows, burning 12 police cars, and fighting with police in what became known as the White Night Riot. The police retaliated by storming the Castro.

The gay community recovered, even thrived—especially economically—but in 1981 the first medical and journalistic reports of a dangerous new disease surfaced. A notice appeared in a Castro pharmacy’s window warning people about “the gay cancer,” later named AIDS. By 1983 the populations most vulnerable to the burgeoning epidemic were publicly identified as gay men in San Francisco and New York City.

San Francisco gay activists were quick to mobilize, starting foundations as early as 1982 to care for the sick, along with public memorials to raise awareness nationwide. By 1990 the disease had killed 10,000 San Franciscans. Local organizations lobbied hard to speed up drug development and FDA approvals. Since then, the city’s network of volunteer organizations and public outreach has been recognized as one of the best global models for combating the disease.

Today the Castro is still the heart of San Francisco’s gay life—though many young hetero families have also moved in. As the gay mecca becomes diluted, debate about the neighborhood’s character and future continues. But the legacy remains, as was evident when a Harvey Milk bust was unveiled in City Hall on May 22, 2008, Milk’s birthday.

Worth Noting

Buena Vista Park.

If you can manage the steep climb, this eucalyptus-filled park has great city views. Be sure to scan the stone rain gutters lining many of the park’s walkways for inscribed names and dates; these are the remains of gravestones left unclaimed when the city closed the Laurel Hill cemetery around 1940. You might also come across used needles and condoms; definitely avoid the park after dark, when these items are left behind. | Haight St. between Lyon

St. and Buena Vista Ave. W,

Haight | 94117.

Quick Bites: Cha Cha Cha. Boisterous Cha Cha Cha serves island cuisine, a mix of Cajun, Southwestern, and Caribbean influences. The decor is Technicolor tropical plastic, and the food is hot and spicy. Try the fried calamari or chili-spiked shrimp, and wash everything down with a pitcher of Cha Cha Cha’s signature sangria. Reservations are not accepted, so expect a wait for dinner. | 1801 Haight St., at Shrader St., Haight | 94117 | 415/386–7670.

Grateful Dead House.

On the outside, this is just one more well-kept Victorian on a street that’s full of them—but true fans of the Dead may find some inspiration at this legendary structure. The three-story house (closed to the public) is tastefully painted in sedate mauves, tans, and teals (no bright tie-dye colors here). | 710 Ashbury St.,

just past Waller St.,

Haight | 94117.

Red Victorian Bed & Breakfast Inn and Peace Center.

By even the most generous accounts, the Summer of Love quickly crashed and burned, and the Haight veered sharply away from the higher goals that inspired that fabled summer. In 1977 Sami Sunchild acquired the Red Vic, built as a hotel in 1904, with the aim of preserving the best of 1960s ideals. She decorated her rooms with 1960s themes—one chamber is called the Flower Child Room—and opened the Peace Arts Gallery on the ground floor. Here you can buy her paintings,

T-shirts, and “meditative art,” along with books about the Haight and prayer flags. Simple, cheap vegan and vegetarian fare is available in the Peace Café, and there’s also a meditation room. | 1665 Haight St.,

Haight | 94117 | 415/864–1978 | www.redvic.com.

Spreckels Mansion.

Not to be confused with the Spreckels Mansion of Pacific Heights, this house was built for sugar baron Richard Spreckels in 1887. Jack London and Ambrose Bierce both lived and wrote here, while more recent residents included musician Graham Nash and actor Danny Glover. The boxy, putty-color Victorian—today a private home—is in mint condition. | 737 Buena Vista Ave. W,

Haight | 94117.

The Castro

Top Attractions

Castro Theatre.

Here’s a classic way to join in the Castro community: grab some popcorn and catch a flick at this gorgeous, 1,500-seat art-deco theater; opened in 1922, it’s the grandest of San Francisco’s few remaining movie palaces. The neon marquee, which stands at the top of the Castro strip, is the neighborhood’s great landmark. The Castro was the fitting host of 2008’s red-carpet preview of Gus Van Sant’s film Milk, starring Sean Penn as openly gay San

Francisco supervisor Harvey Milk. The theater’s elaborate Spanish baroque interior is fairly well preserved. Before many shows the theater’s pipe organ rises from the orchestra pit and an organist plays pop and movie tunes, usually ending with the Jeanette McDonald standard “San Francisco” (go ahead, sing along). The crowd can be enthusiastic and vocal, talking back to the screen as loudly as it talks to them. Classics such as Who’s Afraid of Virginia

Woolf? take on a whole new life, with the assembled beating the actors to the punch and fashioning even snappier comebacks for Elizabeth Taylor. Head here to catch classics, a Fellini film retrospective, or the latest take on same-sex love. | 429 Castro St.,

Castro | 94114 | 415/621–6120 | www.castrotheatre.com.

Worth Noting

Clarke’s Mansion.

Built for attorney Alfred “Nobby” Clarke, this 1892 off-white baroque Queen Anne home was dubbed Clarke’s Folly. (His wife refused to inhabit it because it was in an unfashionable part of town—at the time, anyone who was anyone lived on Nob Hill.) The greenery-shrouded house (now apartments) is a beauty, with dormers, cupolas, rounded bay windows, and huge turrets topped by gold-leaf spheres. | 250 Douglass St.,

between 18th and 19th Sts.,

Castro | 94114.

Quick Bites: Café Flore. Sometimes referred to as Café Floorshow because it’s such a see-and-be-seen place, Café Flore serves coffee drinks, beer, and tasty café fare. It’s a good place to catch the latest Castro gossip. | 2298 Market St., Castro | 94114 | 415/621–8579.

Off the Beaten Path: GLBT Historical Society Museum. Finally in a home of its own, the one-room Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and Transgender (GLBT) Historical Society Museum presents multimedia exhibits from its vast holdings covering San Francisco’s expansive queer history. You might hear the audio tape Harvey Milk made for the community in the event of his assassination, view an exhibit on prominent African-Americans gays and lesbians in the city, and flip through a memory book with pictures and thoughts on some of the more than 20,000 San Franciscans lost to AIDS. Though perhaps not for the faint of heart (those offended by sex toys and photos of lustily frolicking naked people may, well, be offended), this thoughtful display offers an inside look at these communities so integral to the fabric of San Francisco life. | 4127 18 St., Castro | 94114 | 415/621–1107 | www.glbthistory.org | $5, free 1st Wed. of the month | Mon. and Wed.–Sat. 11–7.

Harvey Milk Plaza.

An 18-foot-long rainbow flag, the symbol of gay pride, flies above this plaza named for the man who electrified the city in 1977 by being elected to its Board of Supervisors as an openly gay candidate. In the early 1970s Milk had opened a camera store on the block of Castro Street between 18th and 19th streets. The store became the center for his campaign to open San Francisco’s social and political life to gays and lesbians.

The liberal Milk hadn’t served a full year of his term before he and Mayor George Moscone, also a liberal, were shot in November 1978 at City Hall. The murderer was a conservative ex-supervisor named Dan White, who had recently resigned his post and then became enraged when Moscone wouldn’t reinstate him. Milk and White had often been at odds on the board, and White thought Milk had been part of a cabal to keep him from returning to his post. Milk’s assassination shocked the gay community, which became infuriated when the infamous “Twinkie defense”—that junk food had led to diminished mental capacity—resulted in a manslaughter verdict for White. During the so-called White Night Riot of May 21, 1979, gays and their allies stormed City Hall, torching its lobby and several police cars.

Milk, who had feared assassination, left behind a tape recording in which he urged the community to continue the work he had begun. His legacy is the high visibility of gay people throughout city government; a bust of him was unveiled at City Hall on his birthday in 2008, and the 2008 film Milk gives insight into his life. A plaque at the base of the flagpole lists the names of past and present openly gay and lesbian state and local officials. | Southwest corner of Castro and Market Sts., Castro | 94114.

Randall Museum.

The best thing about visiting this free nature museum for kids may be its tremendous views of San Francisco. Younger kids who are still excited about petting a rabbit, touching a snakeskin, or seeing a live hawk will enjoy a trip here. (Many of the creatures here can’t be released into the wild due to injury or other problems.) The museum sits beneath a hill variously known as Red Rock, Museum Hill, and, correctly, Corona Heights; hike up the steep but short trail for

great, unobstructed city views. TIP

It’s a great resource for local families, but if you’re going to take the kids to just one museum in town, make it the Exploratorium (see the On the Waterfront chapter). | 199 Museum Way,

off Roosevelt Way,

Castro | 94115 | 415/554–9600 | www.randallmuseum.org | Free | Tues.–Sat. 10–5.

Noe Valley

Worth Noting

Axford House.

This mauve house was built in 1877, when Noe Valley was still a rural area, as evidenced by the hayloft in the gable of the adjacent carriage house. The house is perched several feet above the sidewalk. Various types of roses grow in the well-maintained garden that surrounds the house, which is a private home. | 1190 Noe St.,

at 25th St.,

Noe Valley | 94114.

Golden Fire Hydrant.

When all the other fire hydrants went dry during the fire that followed the 1906 earthquake, this one kept pumping. Noe Valley and the Mission District were thus spared the devastation wrought elsewhere in the city, which explains the large number of pre-quake homes here. Every year on April 18 (the anniversary of the quake) folks gather here to share stories about the earthquake, and the famous hydrant gets a fresh coat of gold paint. | Church and

20th Sts.,

southeast corner, across from Dolores Park,

Noe Valley | 94114.

Noe Valley/Sally Brunn Branch Library.

In the early 20th century philanthropist Andrew Carnegie told Americans he would build them elegant libraries if they would fill them with books. A community garden flanks part of the yellow-brick library (completely renovated and reopened in 2008) that Carnegie financed, and there’s a deck (accessed through the children’s book room) with picnic tables where you can relax and admire Carnegie’s inspired structure. | 451 Jersey St.,

Noe Valley | 94114 | 415/355–5707 | Tues. 10–9, Wed. 1–9, Thurs. and Sat. 10–6, Fri. 1–6, Sun. 1–5.

Off the Beaten Path: Twin Peaks. Windswept and desolate Twin Peaks yields sweeping vistas of San Francisco and the neighboring East and North Bay counties. You can get a real feel for the city’s layout here; arrive before the late-afternoon fog turns the view into pea soup in summer. To drive here, head west from Castro Street up Market Street, which eventually becomes Portola Drive. Turn right (north) on Twin Peaks Boulevard and follow the signs to the top. Muni Bus 37–Corbett heads west to Twin Peaks from Market Street. Catch this bus above the Castro Street Muni light-rail station on the island west of Castro at Market Street. | Twin Peaks.

Previous Chapter | Beginning of Chapter | Next Chapter | Table of Contents