3. Something New – The Polyvagal Theory

Very often there are better ways of thinking which open up new vistas and make the unthinkable real and put the impossible within our grasp.

Moshe Feldenkrais

The Polyvagal Theory was proposed and developed by the neuroscientist Dr Stephen Porges. Dr Porges studies the way that the body and brain interact and his Polyvagal Theory is a theory about our developing nervous system and how it affects who we are. ‘Poly’ means many and ‘vagus’ refers to our vagus nerve.

The vagus nerve is a cranial nerve that conveys sensory information about the state of the body’s organs to the central nervous system. It innervates the organs and it communicates the state of the body to the brain. In Latin, vagus means ‘wandering’, and this nerve wanders all over the body, keeping information flowing. There are two parts: an older one and a newer one.

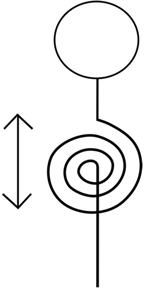

The Polyvagal Theory, in a nutshell, is this. The body has two systems. One runs up and down with the body and brain continuously chatting, communicating about how things are going. When things are running smoothly it is bi-directional – energy goes up and down from toes to head, and back again. There is flow and communication. The other system goes round and round. It rolls through the various organs in your abdomen, making energy and keeping things clean and healthy.

These two systems work side by side, simultaneously. They talk to each other day and night, relaying information and keeping things operating…unless there is a problem.

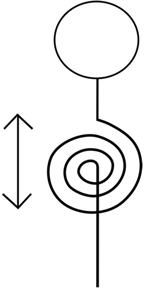

When there is a problem, something threatening like a lion attack, the systems’ flow changes. Suddenly the up and down flow doesn’t happen so well, and the round and round cycle seizes up. All the energy that was previously making you feel well and happy is suddenly being used to put you into red alert.

The energy that once flowed so tranquilly up and down is now being thrust up towards your brain to make you concentrate on the lion. The direction is now all one way. You are in survival mode, you are ready for action. This is the primary survival mechanism, Fight or Flight. The body is primed for action.

Now, ordinarily, once the lion walks away, once the threat passes, this mechanism relaxes and things go back to normal. There is once again room for thinking about other things like smiling and chatting and engaging with the world.

But what if the lion doesn’t walk away? What if he gets closer…and closer…? When this happens, we have another option – to freeze. Like a rabbit caught in the headlights, we can also stop absolutely stock still. When the lion gets too close, we can faint, or go into partial paralysis, or a dead stop. This is called ‘Immobilization’. It is a primary defence: when there is no other option, we play dead.

It really should be called FFI, not just Fight or Flight, because we have three survival mechanisms: Fight or Flight or Immobilization – depending on the level of adversity we are facing. Immobilization is an adaptive function; we use it next, when Fight or Flight is not an option. Porges says that science has mostly forgotten about this function, but that it is vital to understanding not just autism, but depression and all sorts of other human difficulties.

The FFI response is an important part of our safety and security and it can come in very handy. However, it is not so handy if it turns itself on all the time without there being much to worry about, and this is exactly what Dr Stephen Porges thinks happens with autism. He thinks that the FFI system in the autist is a bit, or a lot, twitchy.

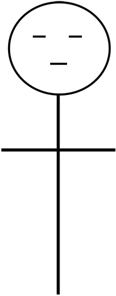

Porges’ ideas examine the notion of safety. When our safety is assured, we are calm and engaged with our world. When our safety is in question, our brain and body talk to each other quite differently. When we are calm we can be open; when we are Immobilized, we are shut off. As a body experience, we are shut down.

The Polyvagal Theory is a massive paradigm shift in understanding behaviour because it stresses the importance of the physiological state – the body – in understanding the mind. The theory is bi-directional; it is not mind over matter. Rather than one being in charge of the other, the brain and the body talk to each other continuously. They talk, they work in tandem. It is a bipartisan relationship.