11. The Process of Discovery and Self-Image

Neurophysiological research shows that all physical activity is organized in the brain by images of the person moving through space.

Anat Baniel

All of this information is interpreted in the context of an internal model of the geometry of the body. The body schema appears to be a device for cross-referencing between sensory modalities, and for guiding through space.

Michael Graziano and Matthew Botvinick

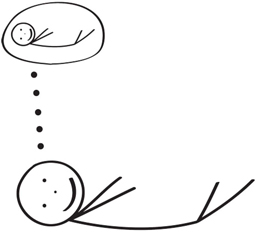

Babies make random movements. They don’t know that the arms and legs are theirs, but they begin to move and gradually it begins to dawn on them that the sensations they are having are their own. They begin to associate their toes, their feet, arms and legs as their own and they begin to represent them in the mind. They begin to visualize movement, to visualize the body; to see the body moving in the mind.

Neurologically, as a baby moves, the movement leaves a trace of information behind in the brain, and the brain registers these movements as neural patterns, neural circuitry. The brain develops patterns of these movements and registers the body parts that belong to them. It begins to form a three-dimensional representation, a picture of the body, in the mind.

As this happens, the baby has more and more control over their body; they know their body is theirs and they can do more and more. They slowly learn that they can take action. They can tell this arm to move, this leg to kick, and this relationship becomes stronger and stronger. As they want to move, they refer to this 3D image of themself to organize the next pattern of movement.

Movement gradually transfers information to the brain and into thought processes. The baby begins both to experience themself in the world and to realize themself as physical form. Information flows between the baby’s growing mind and their growing body. This process of discovery begins very quietly in utero and becomes the baby’s major occupation for the first few years of life.

We organize reality in our minds before we do anything in the physical world

The baby needs to ‘relate’ to their body so that they can tell it what to do. They need to wire it up; they need to belong to their feet and toes, and they to them. They need to synchronize the mind and the body. This is the job of the baby, and it becomes increasingly complex. They begin with the feet and the toes, and gradually engages with integrating the social system.

As adults, unless we have had a problem, we don’t think about moving, we just do it; but babies have to learn this first. Babies are not born knowing how to operate their body. When you are learning to drive, at first you have to be very conscious of everything that you are doing and you start off slowly.

The more you incorporate all the different aspects of the car – the steering, the brakes, the accelerator, the clutch, the road – the more you can drive automatically, without thinking too much. Soon you are out on the highway, among lots of other cars, and your brain can take in the speed, the sounds, the colours, other cars, navigating…and you are set. But first, you have to go really slowly.

Babies, too, have to start off really slowly. They have to become proficient at mastering their body as well as gently setting about the complex task of integrating the sights, sounds and meanings of the world around them. As the baby learns, the movement and the interaction all become natural ways of being – and they all become images in the mind.

But what happens if the baby’s attention is diverted by a vagal system that is not working well, or working in overdrive? What if the baby, instead of learning to orchestrate the flow of information, is busy with the itchy jumper from Granny?

Then, instead of focusing solely on building neural images of itself and its world, the baby’s awareness is on its inner self. The baby is less attuned to the outside world and to the process of integrating the social engagement system. This is possibly what happens with autism. The child, distracted by discomfort or switched to Immobilize, may not develop a strong image of self to refer to when interacting with the world.

Now, what happens if you don’t have a good representation of yourself in your mind? If you can’t see your body in 3D in your mind, how do you ‘see’ it before you move? How do you ‘see’ it walking down the street? How do you ‘see’ it talking in a room full of people? You don’t consciously do all of these things, they mostly happen automatically, but what would happen if you couldn’t do it? Life might get rather confusing.

Think about it. If you are going to clean your room, you sort of see it first, don’t you? And it makes it easier. If you are going to a party, you ‘see’ yourself there having a good time. It may not work out exactly how you wanted, but you get to image yourself and it gives you strength and stability to move into the situation. You can prepare yourself to do something; you can visualize yourself doing well. It is a highly complex act if you think about it. What if you couldn’t do this? What if you didn’t know how? The world might seem a bit complicated; it might be a bit harder to navigate.

It’s possible that autists don’t have that luxury. Studies seem to suggest that the autist has an inability to represent mental states. Possibly this is because they miss some vital steps in the early developmental process.

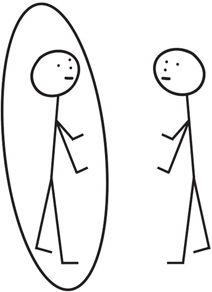

Your 3D brain pattern is your self-image. If you – literally – don’t have a clear self-image, how are you supposed to learn to engage with the world? How are you supposed to take yourself off to a party? How are you supposed to feel strong? What if this platform, that most people take for granted, is not there?

This, together with the Polyvagal Theory, can change the focus of therapy for autists. If the platform, the self-organizing image, is not strong in the autist and if the body is locked in an adrenal response, then using a fix-it model is only going to be of limited use.

So we can teach social skills, we can teach things like eye contact, tying shoelaces and appropriate manners, but – although these things are useful – if the underlying issues are not addressed then not much is being accomplished. We are merely being mechanical.

What we want is to remember quantum physics! We need to remember that the brain is amazing and can – and will – change. It was designed to wire up to the body and it will do it at any age, given the right conditions. Your brain loves making spatial patterns; it loves using the social engagement system and integrating the body, and is really itching to do it for you, at any age.