he next morning, Bob put the boys to work extending an old trail going along the creek—clearing underbrush and building steps from old railroad ties. By the second day, they could anticipate some of Bob’s orders, and they fell into an easy rhythm. When the lunch bell rang, Julian was surprised it was already noon. They walked back to the house, chatting amiably about Bob’s next big project: converting his equipment from gasoline to biodiesel. Julian listened with half an ear, but Danny asked question after question until Bob, in exasperation, sent Julian to the loft to find an article explaining the process in detail.

he next morning, Bob put the boys to work extending an old trail going along the creek—clearing underbrush and building steps from old railroad ties. By the second day, they could anticipate some of Bob’s orders, and they fell into an easy rhythm. When the lunch bell rang, Julian was surprised it was already noon. They walked back to the house, chatting amiably about Bob’s next big project: converting his equipment from gasoline to biodiesel. Julian listened with half an ear, but Danny asked question after question until Bob, in exasperation, sent Julian to the loft to find an article explaining the process in detail.

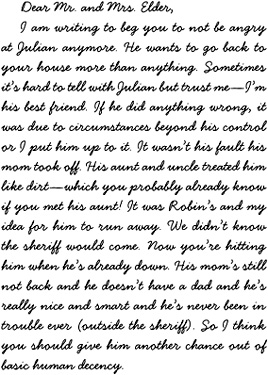

Several stacks of neat papers were piled on top of the computer desk. Julian hesitated, then began leafing methodically through the papers. He finished one stack—bills, invoices, articles clipped from magazines and newspapers—and was halfway through the next when he saw a flash of familiar writing. At first, Julian thought he’d found one of the exchange–student forms they’d faked, but he’d seen all the forms and there’d been nothing like this: a long letter, in Danny’s best handwriting, addressed to “Mr. and Mrs. Elder.”

Julian pulled the paper from the stack and stood, skimming the unfamiliar words.

When he got to the end of the letter, Julian felt a little dizzy. Everything that had happened in the past few weeks he now saw in a new light—Robin’s excited e–mail, Bob’s friendly greeting, Danny’s cheerful demeanor. And somehow, knowing that Bob and Nancy—and maybe even Robin—had read Danny’s letter made him feel exposed, like he’d been walking around in his underwear.

Julian heard Danny bellowing his name from the deck. The last thing he wanted was to be caught snooping. Julian carefully stacked the papers back on top of Danny’s letter and found the biodiesel article in the last pile on the desk.

He started down the spiral stairs, then stopped midway. What would he have done if he were in Danny’s shoes? Probably nothing. But Danny had written the letter in his best handwriting and found the Elders’ address and sent it off. And the letter had worked—it had changed Bob’s mind. He was back at Huckleberry Ranch and he was Julian again, not that boy, and he owed it all to Danny. With a flush of shame, Julian remembered that day at Quantum, when he’d wanted to keep Huckleberry Ranch all to himself.

He stood on the step, his mind turning. He didn’t know what to do with this new information he’d stumbled across. He certainly didn’t want to discuss it with the Elders and he didn’t know what to say to Danny, so Julian simply filed it away in his mind, like a rock in his rock collection that nobody would ever look at but him.

On Friday afternoon, the operatives were finally able to return to Big Tree Grove. Within a few minutes, Robin was up in the tree house. She hung the pulley seat from a metal hook screwed into a thick beam and lowered it jerkily to the forest floor. It was made of weather–beaten green canvas and attached to a complicated system of ropes and pulleys. When it bounded to a stop, Danny made a little bow and swept his hand toward Julian. “After you?”

Julian took a step toward the chair, then stopped himself. “No, you go ahead,” he said. He’d been doing Danny little favors all day—giving him the extra cookie, carrying the heavier tools from the trail. But he still couldn’t shake the feeling that he was somehow in his debt.

Danny gave him a perplexed smile, then climbed into the chair. Julian watched impatiently as he pulled himself up hand over hand. After Ariel had made it to the top and sent the chair back down, Julian finally took his turn. The canvas was rough and smelled faintly of mildew.

Julian reached for a rope.

“No, pull the other one,” Robin shouted down.

Julian pulled with two hands until his feet were dangling in the air.

“That’s it!” Robin said.

Julian rose and rose until he hung slightly above the floor of the tree house. Robin smiled happily. “Do you like it? Isn’t it great?”

Julian grabbed her outstretched hand and climbed onto the deck. Robin wrapped the pulley–seat rope around a metal cleat to secure it while Julian looked about curiously. The front side of the tree house was a deck, about six feet square. Along the side of the deck were long benches with hinged tops that doubled as storage bins. Everything was dusty and covered with leaves and redwood needles and little redwood cones. In the middle of the tree house, the floor narrowed where it was cut around the two giant redwood trunks that jutted up from below. Then the back of the tree house widened out again, like an hourglass, and there was a little cabin with a pointed roof.

Ariel and Danny were walking around the deck, peering in all the storage bins.

“They’re all empty,” Ariel said. “We can put our food and stuff in there.”

“And if it rains, we can go in the cabin,” Julian said.

“You see,” said Robin. “We’re totally safe up here. Nobody can get us.”

“Look here!” Ariel ran her finger along the wooden railing.

“Look at all these initials. A.G. T.C.G. R.W.G. F.C.G.”

Robin studied the letters. “Those must be from the Greeleys. One of the boys was named Tom, I think. Maybe that’s him—T.C.G.”

Julian traced his fingers over the smooth letters. “Here’s more. J.R.E. D.A.E.”

“That’s my brothers!” Robin said. “John Robert Elder. David Armi Elder.”

Danny was looking down at them from the roof. “This is so cool. We can carve our initials too.”

With a pang, Julian remembered his ivory pocketknife. He hadn’t realized it was missing until he began packing for Huckleberry Ranch, and then he couldn’t remember the last time he’d seen it.

“Let’s try to get back tomorrow night. For a test run,” Robin said.

“There’s plenty of room for all of us to sleep here.” Danny hopped down off the roof. “Too bad there’s not a little fireplace. A fireplace and a little DVD player. Then this place would be perfect.”

It’s already perfect, Julian thought to himself. And at the same moment, Ariel said, “It’s already perfect.”

“There actually is an old fire ring down on the ground,” Robin said. “But I don’t think we can arrange the DVD.” She suddenly turned businesslike and clapped her hands together. “OK, everyone! Here’s the plan. We’ll ask my parents if we can all camp out tomorrow night. We’ll bring our sleeping bags and supplies and as much extra as we can. It’ll be a trial run for Operation Redwood.”

“Does your dad know about the tree house?” Julian asked.

“Obviously, the answer is no!” Robin said. “That’s why it’s a secret, remember?”

“What are you going to tell him, then?” Julian didn’t think he could stand being that boy again. He looked at Danny. After all, hadn’t Danny begged Bob to let him come back? Hadn’t he basically promised he wouldn’t cause trouble again? But Danny looked unperturbed.

“I’ll tell him we’re camping in Big Tree, OK? That’s true, right? It’s not even a half–truth, it’s entirely true!” She looked at Julian’s worried face. “We’re not doing anything wrong. Come on, Julian, don’t chicken out on us now!”

That night, for dessert, Nancy barbequed peaches over the coals. She handed Danny and Julian each a heaping bowl topped with vanilla ice cream. “It’s so nice to have you boys around. It reminds me of when John and Dave were your age.”

“The new fence looks great. And we’ve finished a good chunk of that trail too,” Bob said. “It would have taken me weeks to do by myself.”

“I’m helping too,” Molly said, stirring her ice cream around to make a pinkish soup.

“Sure you are, bean sprout. You’re a big help.”

“I’m helping too!” Jo–Jo said. Bob picked him up and started spooning ice cream into his mouth.

Julian ate slowly, matching each bite of warm, sticky peach with a bit of cold ice cream. He was perfectly happy eating his dessert and listening to the pleasant hum of the conversation when he heard Robin’s voice, urgent as always, saying, “Mom, can we camp out in Big Tree tomorrow night?”

Julian ate another bite of ice cream. Everything was so pleasant. Nobody was mad at him. And, if you thought about it, wasn’t Operation Redwood bound to be a failure, like Operation Break–In? They could just spend their last week having fun instead: picking berries and swimming in the river and hanging out in the tree house.

He saw a glance pass between Nancy and Bob. “I don’t see why not,” Nancy said.

“Can I go too?” Molly asked. “Please, Mom?”

“No!” Robin cried. “She’s too little. We want it to be just the four of us!”

Nancy sighed and studied her daughters’ faces, but before she could speak, Bob said, “Now, I don’t see why Molly can’t go with them. She’s been working hard too.”

“Dad! Please! She’s going to ruin everything!”

“Robin, that’s enough,” Bob said sharply. “Molly can join you and you’re going to include her and that’s that. We’ve let you have your friends up here for two weeks, and she doesn’t have anyone. And I don’t want to hear that you’re not being nice to her. Do you understand?” He looked hard at Robin and gave a warning glance to Ariel and the boys.

Robin looked down. Even in the waning light, Julian could see tears in her eyes. She stood up and started grabbing the dishes off the picnic table and taking them inside. Ariel jumped up to help her and Julian and Danny sat awkwardly in the silence.

“Maybe tonight would be a good night for a campfire,” Nancy said with a forced cheeriness. “Why don’t you gather some kindling.”

Danny, Julian, and Molly started scouring the ground for twigs and dry sticks. Jo–Jo followed them around saying, “What are you looking for? Sticks? Are you looking for sticks? Are you gonna start a fire?”

By the time Robin came out with marshmallows, the fire was burning cheerfully. They had a contest for the most perfectly toasted marshmallow. Julian, who had patiently turned his over the coals until it was an even tan, won hands down.

“Your marshmallow’s on fire,” Ariel pointed out to Danny.

“I don’t care. I like them burnt.” He held the flaming marsh–mallow under his face and made a zombie face. “Tonight the moon is full,” he said in a zombie tone, “and I am hungry.”

Jo–Jo started crying and hid his face in his mother’s shirt.

“Shame on you,” Robin said. “Scaring a little child.”

Danny blew out the marshmallow torch with a sheepish grin. “For my penance, I vill eat it.” He stuck the blackened marshmallow into his mouth and pulled it off the stick with his teeth.

As the fire died down, Bob brought out his guitar and Nancy and the girls began singing. They seemed to know an endless number of songs: rounds, nonsense songs, songs about hiking and canoeing and mountains and flowers. Julian and Danny didn’t know any of the words. Finally, at Julian’s insistence, Danny agreed to sing “Lean on Me.” Julian stumbled along with the refrain, and at the end everyone applauded. Later, as the boys crawled into the cold tent, they could still hear Bob picking out the melody to Danny’s song on his guitar.

The following evening, the four operatives, with Molly in tow, began their march toward Big Tree. Their backpacks were loaded down with as much food as they could carry: sandwiches, granola bars, pistachios, beef jerky, carrot sticks, cheese, apples, bottles of juice, and a double batch of chocolate chip cookies. In addition, they were each lugging their own water bottles, sleeping bags, and flashlights. Julian watched Molly’s backpack droop lower and lower. Finally, as they started up the switchbacks, he unhooked her water bottle from her backpack and attached it to his own. Molly gave him a grateful smile.

At the faucet, they caught their breath and refilled their water bottles. It was all downhill from there. Once they crossed the creek, Robin pointed to a peeling wooden shack almost hidden behind a giant redwood. “Take note: the outhouse,” she said with a meaningful grin. When they reached the fairy ring, Robin turned to her sister and said sternly, “OK, Molly, we didn’t want to bring you into this, but we have no choice. We’re going to show you something secret, but you have to promise, cross your heart and hope to die, no crossies, that you won’t tell until we say it’s OK. You can’t tell Mom or Dad unless I specifically say it’s OK or you’ll ruin everything. Do you understand?”

Molly’s pale face glowed in the shade of the trees. She opened her eyes wide and nodded solemnly.

“OK, everyone! Let’s go!” Robin commanded. “We’re almost there.” The others groaned, then readjusted their backpacks and trudged forward. When they reached the fallen tree, they clambered up unsteadily, weighed down by the heavy packs. Molly gave a little cry of surprise as the tree house came into view. “Hey, what’s that?”

Robin ignored her sister until they’d all reached the base of the two giant redwoods and thrown their packs on the ground. “This is our tree house,” Robin finally said. “You weren’t supposed to know about it until you were twelve and then there was supposed to be this really cool initiation with me and John and Dave, but since you insisted on coming, you’re going to miss all that, OK?” Robin looked down at her sister intently. “But the important thing is we have a plan. A secret plan. Do you understand?”

Molly nodded.

“You know how they want to cut down Big Tree Grove?”

Molly nodded again.

“Well, we’re going to stay up in the tree house to protest. Like Julia Butterfly Hill. Remember her?”

“For two years?” Molly’s orange eyebrows shot up in astonishment.

“Not for that long. But as long as we can. That’s us. Not you. You’re too little.”

Molly started to object but Robin cut her off with a fierce stare. “You’re lucky we let you come with us tonight. And this is a secret, remember?”

In a few minutes, Robin was at the top, lowering down the pulley seat. They let Molly have the first ride. She clenched the rope so tightly her knuckles turned white, but the pulley system was foolproof and soon she’d scrambled into the tree house and was waving down at the others.

For dinner that night they had cheese and crackers and carrot sticks and peanut butter and jelly sandwiches, all tasting mildly of bug spray. Robin parceled out two cookies each for dessert. Then, because there were no grown–ups around, she handed out two more. When they were done, the girls spread out their sleeping bags inside the cabin. The boys set up on the deck under the open sky.

Julian looked at his watch. It was just after eight. “What are we going to do now?”

“It’s too early to sleep,” Robin said. “It’s not even dark yet.”

“It will be soon,” Julian said. “The days are getting shorter.” As soon as he said it, he felt a little sad. It made him feel like summer was almost over.

They decided to play hide and seek. They played, searching and tagging and racing through the forest, until they could barely see each other’s faces. Julian was the last one to be It. He found Robin and Ariel hiding together behind a rotting, moss–covered log and Danny inside a burned–out redwood cavity, but Molly was nowhere to be found.

“Help me find Molly,” he said to the others. “I’ve looked everywhere. She’s not under that big fern like the last two times.”

In the vanishing light, they called for her and searched behind every tree and stump. When Molly didn’t answer, the forest seemed to grow a shade darker. Even the sound of her name, ringing out over and over, began to sound ominous. Julian felt like he was in the opening scene of a horror film.

They gathered under the tree house.

“I’m getting worried,” said Ariel. “Maybe she wandered off somewhere.”

The children stood peering into the gloom. A few minutes earlier they had been running around laughing, but now they could barely make out the shapes of the giant trees against the dark sky. An owl hooted and then there was silence. Julian suddenly remembered the bears.

“Let’s get our flashlights,” Robin said. “Come on. We better start a search party.” She turned toward the pulley seat. Only then did they notice that it was not suspended above the ground where they’d left it, but was dangling just above their heads.

“Boo!” cried Molly, her pale face peering over the edge of the seat.

Ariel shrieked. Danny laughed. Julian started breathing again and Robin yelled, “You are crazy, Molly Elizabeth Elder! You scared me to death. Here I was worried sick about you and you’re playing tricks on us!” She gave the chair a shove and sent Molly swinging above their heads.

Molly started giggling. With her legs tucked up and her head bent down she was invisible again.

“That was awesome!” Danny said with admiration. “That was a brilliant hiding place.”

“Go up in the tree house and brush your teeth and send the chair down for the rest of us,” Robin said. “And if you pull another stunt like that, you’re sleeping on the ground tonight, where the salamanders will crawl all over you.”

“I’m going up after Molly. My heart is beating so fast I think I’m going to die,” Ariel said.

Danny was the last one up. He climbed out of the pulley seat and secured the rope around the metal cleat so they would be safe from wild animals, serial killers, or other predators. Molly kept saying, “Were you scared? Did I surprise you? You didn’t see me up there?”

They brushed their teeth, spitting their toothpaste over the railings, and the girls changed into their nightgowns inside the cabin. Finally, everyone settled down in their sleeping bags. When they turned off their flashlights, they were enveloped by the dark night. Julian heard a steady chirping noise and then something scuffling through the dry leaves. A raccoon? A bear? Didn’t mountain lions climb trees?

“Hey! Don’t bears and mountain lions climb trees?” he asked into the night.

“Not redwood trees!” Robin’s voice answered him. “There’s no branches! Where do you guys come up with this stuff!”

It was a clear night. Julian looked up at the millions of stars, so dense and dazzling here. Their light took millions of years to reach Earth. Some of the stars might already be gone, he thought. And by the time they see us, we might be gone too.

The tree creaked softly in the breeze. An owl hooted. He thought of Popo, alone in her house in Sacramento. On the other side of the Earth, in China, the sun would be shining. Star shine and sunshine, somehow he’d never realized they were the same, he thought dreamily, and then he drifted off to sleep.